* After running the Confederates out of Kentucky, General Grant's troops encamped at a site around a Tennessee chapel in the woods named Shiloh Church, to rest and refit for further movements. Grant was not expected to be attacked, and so he was taken by surprise when a Confederate army under General Albert Sidney Johnston smashed into his position. The fighting went on for two days, the battle being the most savage by far fought by the US Army to that time.

* Confederate General Beauregard had quickly recovered from the gloom that had afflicted him after he had ordered the evacuation of Columbus, and began to lay grand plans to consolidate Confederate forces in the region, take the offensive, and drive north to Cairo, Paducah, Saint Louis. The 10,000 men who had left Columbus with General Polk were now in Corinth, joined by 10,000 under Major General Braxton Bragg from Mobile and Pensacola, and 5,000 under Brigadier General Daniel Ruggles from New Orleans. Sending these men northward left the Gulf Coast largely defenseless, but the situation in the upper Mississippi had become critical. The Union seizure of Memphis and Corinth would cut vital rail links extending east to Chattanooga and from there to Knoxville, Richmond, Charleston, Savannah, Atlanta. The Confederacy had to respond.

With his current forces, Beauregard had 25,000 men. Albert Sidney Johnston, leading a force of 15,000 under Hardee and Forrest, arrived in mid-month. When Van Dorn arrived, the total would be roughly 55,000 men, making the Army of the Mississippi the largest army assembled so far in the Confederacy, and a force that Beauregard could use to reverse the Federal drive down the Mississippi.

Albert Sidney Johnston had assumed command on arrival, but he approved of Beauregard's plan, and in fact had been considering similar ideas himself. In a typically graceful gesture, Johnston offered to become department commander and give Beauregard command of the operation. Although Beauregard was vain, he was sensible enough to see that was a cosmetic distinction, and turned down the offer. The two men got down to working their poorly-trained and disorganized army into shape and set up command arrangements to their liking -- dividing the force into four corps, made up of 10,000 men under Polk; 16,000 under Bragg; 7,000 under Hardee; and 7,000 under John C. Breckinridge.

Breckenridge had been a US senator from Kentucky; he remained in the Senate until Kentucky came firmly down on the side of the Union, and then went South. He had joined Albert Sidney Johnston back in the fall, who made the politician a general. Confederate Major General Earl Van Dorn, whose forces had recently been defeated by Union troops in the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, was to bring the survivors across the Mississippi River, to constitute a fifth corps. However, Van Dorn's force didn't arrive in time to take part in Johnston's offensive.

The Confederate target was only 20 miles (32 kilometers) to the north, in the vicinity of a backwoods meetinghouse named Shiloh Chapel along the Tennessee River, where U.S. Grant was massing his own forces, while Johnston and Beauregard were massing theirs.

* After regaining command, Grant had steamed upstream to Savannah, Tennessee, on the east bank of the Tennessee River, where C.F. Smith had set up his headquarters. One of Grant's divisions was at Crump's Landing, three miles (4.8 kilometers) upstream to the south on the west bank of the Tennessee, while another five divisions were sent ashore six miles (9.6 kilometers) south of that, at a place called Pittsburg Landing, also on the west side of the river. The site had been recommended by William Tecumseh Sherman, who was now back in the field and commanding one of the divisions.

Despite his loss of nerve in the fall, Sherman had returned to duty in Saint Louis before Christmas, demonstrated considerable energy in organizing logistics for the seizure of Fort Donelson, and had been returned to combat command. Grant had a high opinion of him, and Halleck had decided that Sherman wasn't really crazy, just exciteable. Besides, Sherman had a brother -- John Sherman, later the architect of the landmark Sherman Antitrust Act -- in the United States Senate, and it didn't hurt to make powerful men happy.

Sherman's men had not been so certain of him at first, but in mid-month he had steamed them up the Tennessee past the Mississippi state line to cut the vital Memphis and Charleston Railroad. They had disembarked from their transports at midnight in a driving rainstorm, found bridges washed out, losing some cavalrymen to the flood in the process, and realized they were in danger of being stranded by waters rising behind their advance. Sherman had canceled the operation and led them back to the transports. It had seemed quite a fiasco, except that Sherman had kept his head under pressure and made all the right decisions. Like Grant's bloodying at Belmont a few months previously, it had been a useful exercise for both commander and men, giving them mutual confidence.

Pittsburg Landing itself was little more than a narrow shelf, backed by high bluffs, which in turn led to a plateau dotted with farm clearings and second-growth timber. Sherman found it conveniently crisscrossed with roads and protected by streams -- Owl Creek running along the west side, Snake Creek along the north -- with plenty of space to bivouac and drill five divisions of soldiers. The only building in the area of any note was Shiloh Chapel, towards the southern end of the campground, so the place was informally known as Camp Shiloh.

Halleck was cautious as always, sending orders to Grant to dig in and wait for instructions. However, nobody was digging in at Pittsburg Landing. C.F. Smith was in bed, having scraped his leg on the seat of a rowboat and come down with an infection, but would have none of such timidity: "By God, I ask nothing better than to have the rebels come out and attack us! We can whip them to hell. Our men suppose we have come here to fight, and if we begin to spade it will make them think we fear the enemy." Grant agreed, telling Halleck the war was on its last legs and the enemy was too demoralized to be dangerous. Sherman didn't agree, telling reporters privately that "we are in great danger here" -- but having been overwhelmed by his fears a few months before, he gradually went to the other extreme and let them go to sleep.

Grant had over 42,000 men in his six divisions. Now that Halleck was the top boss in Tennessee, Buell and 30,000 soldiers were being sent as reinforcements. With such a combined force, the Federals would make short work of the rebels at Corinth. Albert Sidney Johnston knew all this, and knew he would have to strike Grant before Buell and his men arrived, or face total destruction.

* The collision between the Union and the Confederate armies in Western Tennessee was set into motion on the evening of 2 April, when Beauregard received a telegram with intelligence stating that Grant's men were preparing to move on Memphis. Beauregard forwarded the telegram to Albert Sidney Johnston, along with a suggestion that it was time to move against the Federals.

Johnston was not keen on the idea, since his army was poorly trained and drilled and Van Dorn had not arrived with his reinforcements. However, on conferring with Braxton Bragg, who had become his chief of staff, Johnston was convinced that they needed to move immediately, before Buell arrived to reinforce Grant. Johnston's intelligence had given him a correct assessment of the poor state of readiness at the Federal camp. If he moved quickly, he could take the Yankees by surprise.

Beauregard issued orders to begin the march, and then things started to go wrong. Beauregard's inclination toward grand schemes led him to order a coordinated overnight march along two routes that would meet up in attack formation at Pittsburg Landing. This plan might have been practical with veteran soldiers, but it was completely unrealistic with raw recruits. When the columns set out from Corinth on Thursday, 3 April, they were late and quickly got into traffic jams. By nightfall, they had covered less than half the distance to Pittsburg Landing, and were seriously behind schedule.

Thursday was bad; Friday was a nightmare. Rain began to fall, bogging the columns down in mud, and the confusion that had prevailed the day before only grew worse, with divisions getting lost and tangled and everyone in bad temper. The confusion carried over into Saturday. When the rain stopped and the sun came out, the undisciplined troops tested the quality of their powder by firing into the air. It seemed impossible to believe that the Federals hadn't been alerted to their presence. After all, they were so close that Beauregard could hear drumming from Camp Shiloh.

Beauregard was angry and discouraged. He wanted to call off the attack: "There is no chance for surprise. Now they will be entrenched to the eyes." Furthermore, Buell had almost certainly arrived with his reinforcements and the Confederates would find themselves seriously outnumbered. Johnston conferred with his other generals. He asked Polk, Bragg, and Breckinridge what they thought; Hardee wasn't present at the meeting. Polk replied that if his men retreated without a fight they would feel defeated, and Bragg and Breckinridge emphatically agreed. They'd come for a fight, and so they would have one. Johnston gave his judgement: "Gentlemen, we shall attack at daylight tomorrow." The rebel soldiers bedded down in positions where they would be ready to attack the moment they woke up in the morning.

Buell had actually arrived downriver, though with only one division; the rest of his men were strung out along the road from Nashville. Grant was pleased to see the reinforcements arrive, and once they were all present, he would move on Corinth. William Tecumseh Sherman was effectively in charge of the site at Camp Shiloh for the moment. He was getting warnings of skirmishes along his picket line to the south and reports of Confederate movements beyond that line, but though he reported the clashes to Grant, he complacently concluded: "I do not apprehend anything like an attack on our position."

BACK_TO_TOP* The next morning -- Sunday, 6 April 1862 -- Beauregard went to Albert Sidney Johnston to beg him once more to call off the attack. Before Johnston could reply, he was interrupted by the sound of musketry and the firing of cannon. Johnston said: "The battle has opened, gentlemen. It is too late to change our dispositions." Beauregard got on his horse and rode off to the battle. Johnston mounted as well, sat there for a moment collecting himself, and then turned towards the fighting himself, telling his staff: "Tonight we water our horses in the Tennessee River."

The fight had started before the jump-off time. A Federal officer had sent out a handful of companies to investigate rebel activities, and the Union soldiers had quickly got into a shootout. They fell back and gave frantic warnings of the attack now falling on the Federal camp. A captain who went to investigate came back in a hurry shouting: "The rebs are out there thicker than fleas on a dog's back!"

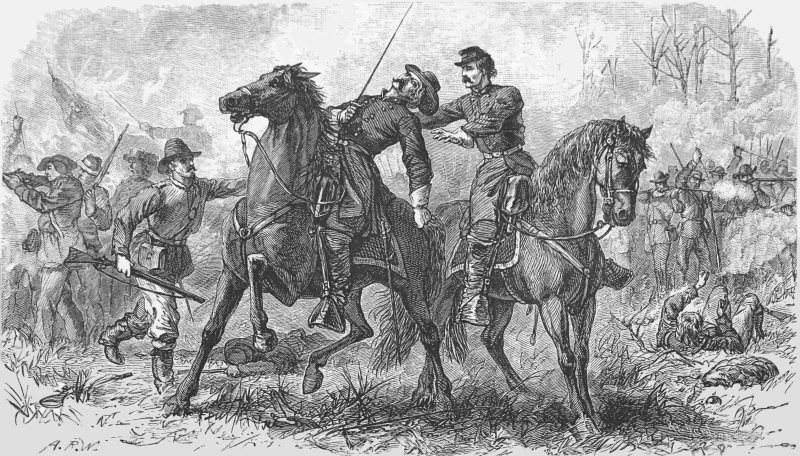

A courier was sent to Sherman, who replied blandly: "You must be badly scared over there." Sherman went with an orderly, Private Thomas Holliday, to check the reports for himself and saw the long rows of Confederates advancing across a field. Rebel skirmishers broke through the brush and a lieutenant shouted to Sherman: "General, look to your right!"

Sherman threw up his arm as if to ward off bullets and shouted: "My God, we're attacked!" The rebels fired a volley that killed Private Holliday immediately and wounded Sherman in the hand. Sherman called out to the colonel in charge of the regiment on the spot: "Hold your position, I'll support you!" -- and then spurred his horse to gallop off and alert his men. Though the colonel and many of his men fled, the rest of the troops stood their ground long enough to give Sherman time to move his soldiers into line along the ridge where they were camped. The Federals held their ground against four charges, laying murderous fire into the ranks of Confederates, and then fell back in fair order when the rebels charged a fifth time. One Mississippi regiment that had begun the fight with 425 men had only 100 left by the time they made the ridge, leaving so many dead and wounded in the valley below that a man could have walked across on their bodies.

Sherman's division held the line on the western part of the battlefield. A second division under McClernand held the center, near Shiloh Chapel, and a third division under Brigadier General Benjamin M. Prentiss, an Illinois merchant who had been born and raised in Virginia, held the east. Some men were fading away to the rear, but most were holding their ground and fighting.

Sherman was moving among his men and encouraging them to stand fast. He'd been wounded twice, the wound in the hand that he had taken at the outset of the battle plus a nick across the shoulder, and had four horses shot out from underneath him. Despite his injuries and his exciteable nature, Sherman remained cool, riding about upright while bullets flew about, organizing his defense. The unstrung Sherman of the previous fall was a thing of the past. When a headquarters aide came up to see how things were going, Sherman told him, matter-of-factly: "Tell Grant if he has any men to spare I can use them. If not, I will do the best I can. We are holding them pretty well just now. Pretty well; but it's hot as hell."

* Grant had abandoned his breakfast when he heard the sound of cannon fire from the south. He told his staff: "Gentlemen, the ball is in motion. Let's be off." Grant jotted off two notes. One went to Buell, telling him not to worry about meeting with him for the moment. The second went to Brigadier General William Nelson, who had brought Buell's lead division there the day before, and instructed Nelson to move his men down the east side of the river to the bank opposite Pittsburg Landing. Grant then took a steamship up the river.

At 8:30, he passed the jetty at Crump's Landing and found the commander of the division camped there, Major General Lew Wallace, waiting for him. Grant called out to Wallace as the vessel steamed past: "General, get your troops under arms and have them ready to move at a moment's notice!" Wallace shouted back: "I have already done so!" Grant disembarked at Pittsburg Landing and rode up towards the firing lines. He'd badly sprained his ankle when his horse had fallen during a thunderstorm two nights before, and was having trouble getting around on foot. The first thing he did was form up a straggler line to catch soldiers leaving the battle, and form them up in a rear line of defense.

The divisions of Sherman, McClernand, and Prentiss were in the thick of the fighting. There were two other divisions behind them, including C.F. Smith's division, now under Brigadier General W.H.L. Wallace, an Ohio lawyer who had fought in Mexico; and a division under Brigadier General Stephen Hurlbut, an Illinois lawyer who originally had come from Charleston, South Carolina. These two divisions had formed up behind the front line of fighting and were sending reinforcements forward. By the time Grant reached them, he had decided to commit his reserves, and sent messages to Lew Wallace and William Nelson to order them to move up as fast as possible.

By 10:00, Grant was in the front with Sherman, who had been forced to fall back from his original position and take up a new line. One of Sherman's brigades had disintegrated, but the other two on the line were holding fast. Sherman worried about running out of ammunition, but Grant assured him that more was on the way. Grant then rode east to check on McClernand, who was holding the line north of Shiloh Chapel; and then to Prentiss, whose men were making a stand in a road -- later described as "sunken", though it appears to have been rutted at most. Prentiss's division had been badly cut up, but reinforcements from the divisions of W.H.L. Wallace and Hurlbut arrived to brace the defense.

The fight there was so severe that a soldier later told of a terrified wild rabbit coming out of the brush and snuggling up to a prone soldier for comfort. Grant had now committed all his available reserves, and a Confederate breakthrough would throw his army into the Tennessee. He sent two officers northward to see what was taking Lew Wallace so long, and sent a note to Nelson indicating extreme urgency, telling him the rebel force was estimated at over 100,000 men.

On the other side of the firing line, Beauregard directed the flow of reinforcements to the attack from his combat headquarters at Shiloh Chapel. In the meantime, Albert Sidney Johnston rode among his men, encouraging them by his words and example.

Keeping the assault on track took diligence. Some regiments could not face the bloodshed, though most fought hard. There were the inevitable mistakes of battle. The New Orleans Guard Battalion, which counted P.G.T. Beauregard as an honorary private, absent on duty, wore their blue militia uniforms into battle. They were unsurprisingly fired upon by the Confederates they were marching to support. They returned fire, and when an officer rode up in a lather to tell them they were shooting at friends, the regimental colonel replied: "I know it, but dammit sir, we fire at everybody who fires on us!" The Guards decided to turn their jackets inside out, showing off a white lining that made them vivid targets, but at least didn't draw the fire of friends.

A bigger problem was straggling in the ranks, more from hunger than anything. The Yankees had been surprised at their breakfast by the dawn attack, and the food that still lay spread out on tables was more than starved rebel soldiers could resist. Others rummaged through the campsite from curiosity or in search of loot.

The worst problem, however, was simply that the attack was bogging down because of the irregular terrain and stubborn Federal resistance. The sheer chaos of battle was destroying the organization of the Confederate force, reducing it to disconnected gangs of fighting men. Johnston wanted to push up the riverbank to cut the Federals off from the river and force them to surrender, but although Sherman and McClernand had fallen back, Union troops were still stubbornly holding out from the sunken road.

"It's a hornet's nest in there!" rebel soldiers cried after each time they were thrown back, leaving bodies laid in piles, many of them horribly mutilated and dismembered by cannon fire. Johnston went forward to correct this problem. To the east of the "Hornet's Nest", as it would forever be known, some of Hurlbut's men were holding the line from a peach orchard. Johnston arrived just after they had driven off a rebel attack, and the Confederate officers were to little surprise having trouble persuading their men to go forward again.

Johnston rode among them, saying: "Men! They are stubborn! We must use the bayonet!" The men formed up but hesitated to move forward, so Johnston went front and center and called out: "I will lead you!" Johnston rode forward and the men followed, driving the Yankees out of the orchard. Johnston came back, exhilarated and excited, with his uniform torn and a bootsole shot in half by a bullet. A few moments later, his aide, Governor Isham Harris of Tennessee, saw Johnston go faint in the saddle. Harris cried: "General, are you hurt?"

Johnston replied: "Yes, and I fear seriously." Harris led the general to a nearby ravine, eased him off his horse, and looked him over for wounds. He found Johnston's right boot full of blood and traced it back to a severed femoral artery. Johnston's doctor was attending to some wounded Federal prisoners, and the governor did not know how to apply a tourniquet. Harris fumbled anxiously while the blood flowed, until it stopped, and he realized Johnston was dead. Johnston was 59 years old.

* It was about 2:30 in the afternoon. When the news reached Beauregard, he gave orders that the general's death not be announced to the men lest it demoralize them. The attack would continue, and in particular the Hornet's Nest would be wiped out. It had not occurred to Johnston and did not occur to Beauregard that it might have been more profitable to simply bottle up the troublesome Federals there, and throw the weight of the attack onto the weaker Union forces that were already giving way.

In the Hornet's Nest, the Union defenders had had driven off repeated attacks, leaving the ground in front of their position carpeted with dead and wounded Confederates. Johnston's charge had been the death of him, but it had left the Federals exposed on their flank. Now the rebels massed 62 cannon and, after gathering their forces for one final, overwhelming assault, opened up on the Federals with a pounding barrage that forced them back. W.H.L. Wallace was wounded horribly in the head while trying to rally his men and left on the battlefield. The Confederates moved around and sealed off the Hornet's Nest. The surrounded Federals continued to fight for a few hours, but ultimately the survivors had to surrender; Prentiss was among the captured. Some Federals smashed their muskets against trees to keep the rebels from taking them, and were shot by their captors.

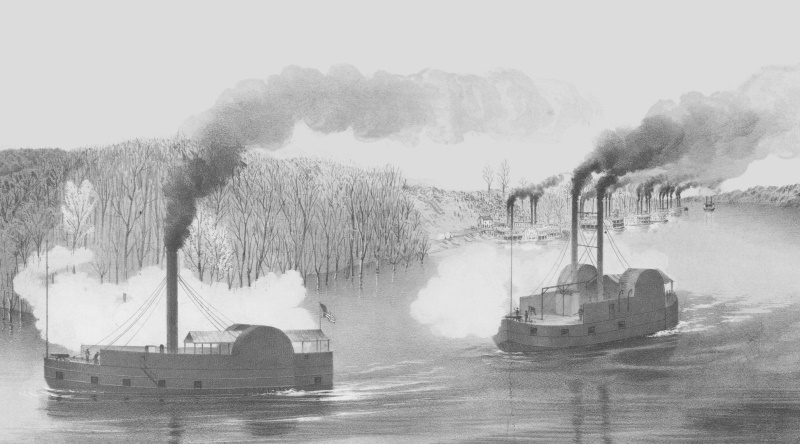

Beauregard was in fine spirits. The rebels had driven the Union soldiers from every stand they had made, the Confederates had captured dozens of cannon, and it seemed one more big push would finish the Yankees. The reality was that his troops didn't have one more big push left in them, and the Yankees were far from feeling beaten. Beauregard's orders went out and the soldiers went forward, but they were too exhausted, confused, and cut to pieces to go much further. While the Federals had been forced back, they had done so in tolerably good order, had formed up in yet another defensive line -- this one very strong -- and were not about to cave in. Furthermore, though Foote's ironclads were at Island Ten, Grant still had the two wooden gunboats TYLER and LEXINGTON, and they gave the rebels the best pounding they could.

Despite their lack of training, the Confederates had for the most part fought with supreme endurance, but they were now at their limit. Beauregard sent out couriers to call back the attack for the day, though the fighting had already fizzled out on its own. He would renew the attack in the morning and destroy Grant's army once and for all. Unfortunately, the disorganization that had been creeping up on the rebel army all day was by nightfall almost complete. Along with the ghastly numbers of killed and wounded, the abundance of food and other supplies lying around on the battlefield was too great a temptation to resist; many Confederates spent much of the night picking up loot. The rebel assault had shot its bolt.

* Grant had been impatiently waiting the arrival of Lew Wallace and his division for hours. They didn't arrive until 7:00 PM, a mixup in marching orders having taken them down the wrong road; Wallace would find himself on Grant's blacklist from then on. They went into line with the rest. In the meantime, the first of Buell's new reinforcements were being ferried across the Tennessee to Pittsburg Landing. General William Nelson was enraged to find the landing packed with terrorized and confused fugitives from the battle, with some of them trying to swim across the river.

The fresh troops pushed through the skulkers and went up to the line. One Kentucky regiment passed Sherman as they moved up. This particular group had been under Sherman when he had lost his nerve at Louisville so many months ago and had few good memories of him, but now he was literally blooded in battle -- his face blackened by powder, his hat brim torn away by shrapnel, his hand wrapped in a dirty bandage. He greeted the men; in return, they raised their caps on their bayonets and gave him a rousing cheer. It wasn't something Sherman was used to, and it made a profound impression on him.

The two armies settled down for the night in expectation of more fighting the next day. At midnight, a violent thunderstorm poured down the battleground, with thunderbolts lighting up the figures of the dead that lay strewn everywhere, while the wounded cried out for help as all were soaked to the skin. The corpses lay in heaps and pigs gorged on the bodies. Blood ran literally in rivulets across the battlefield. One rebel later wrote: "O it was too shocking too horrible, God grant that I may never be a partaker in such scenes again ... when released from this I shall ever be an advocate of peace."

The hopes of Beauregard and many of his soldiers that the battle would be quickly tied up in the morning would have turned to ash if they had known that reinforcements were pouring into Grant's position. Sherman ran into Grant after dark and said: "Well, Grant, we've had the devil's own day, haven't we?" Grant replied: "Yes. Lick 'em tomorrow, though."

Grant had lost two divisions, the three others that had been in the fight had been badly cut up, and the rear of the battle line was crowded with thousands of the faint-hearted. Still, most of the soldiers were standing fast in good defensive positions, Lew Wallace and Nelson were in place with their men, and two more of Buell's divisions were trickling in to join them. By morning, Grant would have made good his losses, and then some -- to move against rebel divisions that had been badly cut up themselves.

One rebel could see what was going on. Bedford Forrest was not the kind of officer to simply assume things were all right, and sent out a scouting party wearing Union jackets after dark. The scouts quickly detected Buell's men going ashore. Forrest realized that Beauregard would either have to stage a night attack or pull out. Unfortunately, Forrest could not find Beauregard. He warned every officer he could find, but they had either lost contact with their men, or did not feel they had the authority to act. When Hardee simply told Forrest to go back to his post, Forrest stomped off angrily, telling Hardee: "If the enemy comes on us in the morning, we'll be whipped like hell." An aide describe Forrest as "so mad he stunk."

In the meantime, Beauregard was sleeping contentedly in Sherman's captured tent. Beauregard had received a telegram from Alabama, sent by a Colonel Ben Hardin Helm, who happened to be President Lincoln's brother-in-law, saying that Buell was known to be marching towards the Georgia line and would not be able to reinforce Grant. Beauregard's chief of staff, who was sharing a tent with the captured General Prentiss, was equally cheerful. Prentiss was unimpressed: "You gentlemen have had your way today, but it will be very different tomorrow. You'll see. Buell will effect a junction with Grant tonight, and we'll turn the tables on you in the morning."

BACK_TO_TOP* All through the night, the two Union gunboats fired 11-inch (28-centimeter) shells into the rebel lines at intervals of roughly fifteen minutes, terrorizing Confederate troops. As daylight came, the sounds of fighting began to increase steadily. Prentiss sat up abruptly and told his companion: "There is Buell! Didn't I tell you so?!"

Grant was pressing forward with the four divisions he had left, plus three provided by Buell, under Brigadier Generals William Nelson, Alexander D. McCook, and Thomas L. Crittenden, brother of Confederate General George Crittenden, who had come to ruin at Logan's Crossroads. After an early bombardment, the Federals jumped off at 7:00 AM, making steady progress at first. Buell's men had never seen real combat before, but they adjusted to it quickly. One Indiana colonel, who found his men too shaky in their advance, halted them on the battlefield and put them through a formal manual of arms. The ritual of the familiar, even in such a deadly environment, seemed to steady their nerves, and they then returned more resolutely to their advance.

By noon, the Federals were closing into on Shiloh Chapel, but rebel resistance had stiffened. Beauregard had recovered from his initial surprise and was doing his best to rally his increasingly confused army. Despite what had happened to Johnston the day before, Beauregard twice seized the colors of faltering regiments and fearlessly led them against Union soldiers. There was no hope of regaining the initiative, however, and the rebels were being chewed to pieces. By about 2:00 PM, Governor Harris, now Beauregard's aide, went to the general and suggested: "General, do you not think our troops are very much in the condition of a lump of sugar thoroughly soaked in water, preserving its original shape, though ready to dissolve? Would it not be judicious to get away with what we have?"

Beauregard was cool as he nodded and answered: "I intend to withdraw in a few minutes." The orders went out, and by 4:00 PM the rebels had pulled off the firing line in surprisingly good order. The Federals did not pursue. Although they now owned the battlefield, they had taken a terrible beating themselves and were too exhausted to do more than sweep up the pieces. As chewed up as they were, however, they were still better off than the rebels.

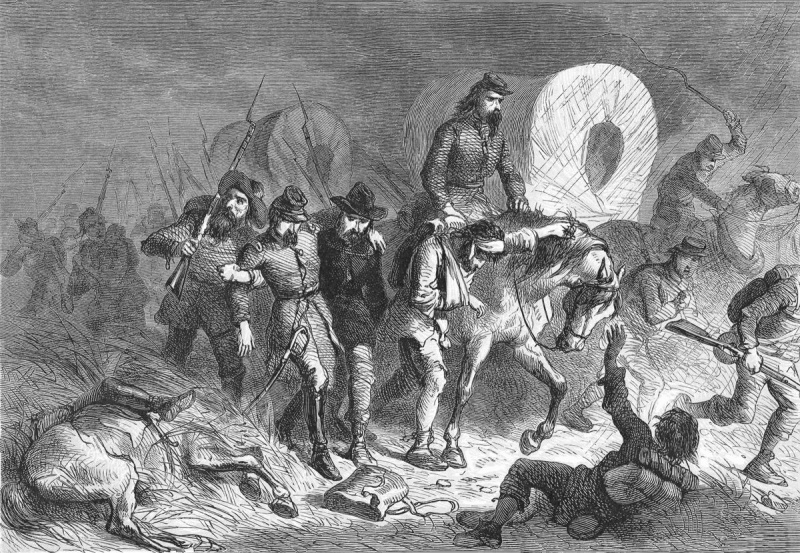

It had rained intermittently during Monday's battle, and as darkness fell and the rebel army filed down the road to Corinth, a howling spring storm broke out, drenching everyone, turning the roads into quagmires, and pounding the helpless wounded with huge hailstones. Through it all, Beauregard rode up and down the column, pressing the men on and comforting them.

The last rebels were on the road by Tuesday morning; Sherman followed with a brigade to make sure they did not hang around. Four miles (6.4 kilometers) down the road to Corinth, at a place called Fallen Timbers, he ran into the cavalry rearguard of Beauregard's army. There were about 350 Confederate horsemen, outnumbered by about 5 to 1 by Sherman's brigade, but they were led by Bedford Forrest, who had an extraordinary ability to cheat the odds. Fallen Timbers had received its name because it had been partly logged before the war, and it was the kind of terrain through which an orderly advance was impossible. Forrest gave the order to charge. His cavalrymen swept down on the Yankees, throwing the Federal front ranks into confusion and sending Sherman and his staff fleeing through the mud.

The rebels were still outnumbered and Forrest, driving forward, suddenly found himself surrounded by Federal infantry who were screaming: "Kill him! Kill the goddam rebel! Knock him off his horse!" Forrest wheeled and slashed, and then a bluecoat shoved a rifle into his back and fired, blasting Forrest up from the saddle. Forrest responded by grabbing a Union soldier, hoisting him up to use as a shield, and then galloped off to safety, tossing off his captive when he had got out of range. That was the end of it. Sherman's men were exhausted by three days' fighting and there was no more to be done. He ordered them back to camp.

The Federals were badly bloodied and worn out. An endless stream of wounded flowed back to field hospitals, and burial of dead men and animals presented work details with a miserable and appalling task.

General W.H.L. Wallace was found alive on the battlefield, despite his hideous wound. A musket ball had gone in the side of his head and come out through his left eye. He had been wrapped in a blanket by a kindly Confederate. Wallace's wife had arrived on Sunday to visit her husband. With the battle howling all around her, she had kept her wits by tending to the wounded, and kept her dignity when she was told that the man had fallen in battle.

When they brought the wounded general in the next day, he was strong enough to recognize the woman and clasp her hand, and she hoped he would live, but the wound grew infected and like so many of the other wounded, he died a few days later. His wife said: "He faded away like a fire going out." Prentiss would later inflate the role of his division in the defense of the Hornet's Nest, though Wallace's troops deserved much of the credit; without contradiction, Prentiss's version of the story ended up in history books.

* In tactical terms, the battle was a draw. Beauregard still regarded it as a victory and sent messages to Van Dorn, telling him to hurry so they could give the Yankees another whipping. Jefferson Davis announced it as such, though he was greatly saddened by the death of Albert Sidney Johnston. The rebels had in fact succeeded in blunting the Federal drive down the Mississippi. On the Union side, General Halleck reacted as though Grant's army was now in imminent danger of complete destruction, and rushed up the Tennessee to take personal command. However, slowing down the Federal advance only bought the rebels time; they really needed to retake the initiative, and in that they failed.

What was unambiguous was that the casualties had been frightful, with losses of almost a quarter of the forces involved. The rebels had lost almost 11,000 men, the Federals over 13,000. The sum was more than all the casualties inflicted in all battles Americans had fought to that time. The news horrified the public, North and South, and if there had been doubts that the war would be long and bloody, Shiloh put them to rest for good. Nobody absorbed the lesson better than U.S. Grant: "I gave up the idea of saving the Union except by complete conquest."

For the time being, however, Grant was sidelined, bearing the brunt of criticisms for the bloodbath at Shiloh. Halleck arrived on 11 April and took direct command, with Grant appointed "second in command" and hung out to dry. Rumors had been circulating in the rear about the lack of Federal preparedness before the battle, which was a fact, and Grant's laziness and drunkenness, which were not. Ohio citizens, newspapers, and politicians were particularly angry at Grant because a large proportion of the Union boys killed in the fight were from that state.

The lieutenant governor of Ohio reported after a fact-finding trip of "a general feeling among the most intelligent men that Grant and Prentiss ought to be court-martialed or shot." Other states picked up the cry, and eventually a Pennsylvania spokesman took the case to President Lincoln, suggesting that Grant be dismissed. Lincoln sat and thought it over for a moment, and then famously replied: "I can't spare this man. He fights."

BACK_TO_TOP