* The bloodletting at Shiloh left General Grant in disgrace. However, it was not at all a Confederate victory, and the Federals pushed their advantage. John Pope finally overran the Confederate strongpoint on Island Number 10, opening the Mississippi for further progress of Union warships. Under the command of Major General Henry Halleck, the Union Army conducted a glacially slow advance on the Confederate base at Corinth, Mississippi, with rebel forces abandoning the town to the Federals. More decisively, a Union river armada crushed a Confederate fleet at Memphis, Tennessee, capturing the city.

* The ghastly news from Shiloh was a shock to the North, not all the news from the West was so grim. John Pope, a major general as of late March, had been frustrated in his effort to capture Island Ten by Commodore Foote's refusal to run the rebel guns. Two weeks of bombarding the Confederate defenses with mortar boats had shown little effect, and until General Pope obtained naval firepower downstream he wouldn't be able to move across the Mississippi and take Tiptonville, isolating the rebel garrison at Island Ten.

Pope was so desperate to get his hands on an ironclad that he had telegraphed Halleck, suggesting that Foote give up two of his ironclads and let Pope's men run them downstream. That exercise didn't go anywhere, but some of the naval officers were impatient as well -- in particular, Commander Henry Walke, the 54-year-old commander of the ironclad CARONDELET. Walke had been humiliated by the beating his vessel had taken at Fort Donelson and wanted to make up for it. In a conference of war held at the end of March, he expressed his belief that he could make the run past Island Ten in the dark of the night. Foote was uncertain, but pleased at Walke's initiative, and gave him the go-ahead.

Walke spent a week getting ready for the dash. He was ready by the night of 4 April, when the moon would be new and set early. His men had reinforced the CARONDELET with whatever armor they could improvise, such as planks, cordwood, and chains, and a coal barge loaded with bales of hay was lashed to the port side. She looked, as one witness put it, like a "farmer's wagon prepared for market". The vessel was rigged for blackout running and the steam exhaust, which made the gunboat sound like a locomotive engine under normal circumstances, was muffled by routing it through the paddle-wheel housing.

To prevent the vessel from being seized by Confederate boarders, the crew was armed, and two dozen volunteer sharpshooters were taken on board. Hot water hoses were rigged to the boilers, and Walke was prepared to scuttle her if worst came to worst. As additional insurance, Foote ordered a raiding party to disable the northernmost battery of the Confederate defenses. On the night of 1 April, Colonel George Roberts of the 42nd Illinois and his fifty men rowed downriver in a thunderstorm. A flash of lightning gave them away, but the raiders moved in fast, overwhelmed the defenders, spiked the six guns, and rowed back to the fleet. It was neatly done.

The moon went down at 10:00 PM on the night of 6 April. It was cloudy and utterly black. The CARONDELET made steady, quiet progress towards the rebel batteries and it seemed as though the Federals might make their passage completely undetected -- but then a wild storm broke out, bathing the vessel in thunder and lightning. Walke was certain the gunboat would be detected, but it made it past the first battery without trouble, and then the soot in the CARONDELET's smokestacks, normally kept damp by the steam exhaust, caught fire and sent blasts of flame from the top of the stacks.

The rebels ran to battle stations and tried to fire on the black gunboat gliding down the river past their guns in the storm, but their aim was poor and the CARONDELET was unharmed, though a pair of cannonballs were later found in the barge and a bale of hay. She arrived downstream at New Madrid at midnight, to be greeted by the cheers of army artillerists.

After a day's delay, the CARONDELET set down the river on 6 April to attack rebel batteries on the Tennessee shore. That night, Foote, his enthusiasm rekindled, sent the PITTSBURGH downstream to join the CARONDELET. On the 7th the two gunboats took up the bombardment together, providing cover for transports that took Pope's men across the river. With the Yankees closing in, most of the garrison at Island Ten tried to run for it. Those that remained behind surrendered that night, while those who had fled found themselves boxed in by Pope's soldiers and surrendered on the morning of the 8th.

Pope was a hero. He had captured roughly 7,000 Confederates and piles of weapons and supplies, at a cost of less than a hundred casualties. Pope had shown both ingenuity and drive, while the rebels had passively let themselves be swallowed up. The Union was in need of heroes, and he was praised accordingly, with few having any occasion to wonder what might happen if Pope encountered rebels who weren't so conveniently passive.

The next objective was Fort Pillow; the Confederates had been building it up ever since the fall of New Madrid, and Pope and Foote made plans to move against it. However, Halleck had other plans. Seizing Corinth, Mississippi, would leave Fort Pillow hanging to eventually fall of its own dead weight. Pope was ordered to take himself and his men to Pittsburg Landing to join Grant and Buell. Together, the combined forces would amount to roughly 100,000 men.

* The fall of Island Ten had undermined the faltering Confederate defense of the region. Despite Beauregard's assertions of "victory", his forces were in a precarious position and he had no real means of changing the balance back in his favor. Flag Officer Andrew Foote was feeling encouraged, taking his ironclads and mortar boats downstream towards Fort Pillow in mid-April, feeling excited at the prospect of taking the place.

Then Halleck had ordered Pope and his soldiers away. There was no way that Foote's warships could take Fort Pillow by simple intimidation, since the place was situated on high bluffs overlooking the river and well-armed with cannon. There was nothing very useful to do. Foote kept his fleet anchored five miles (8 kilometers) upriver from Fort Pillow, except a single gunboat and mortar boat. The gunboat stood guard, while every half-hour during the day the mortar boat lobbed a 13-inch, 200-pound (33-centimeter, 90-kilogram) shell into the fort "to the great interest and excitement of the occupants."

It was boring and pointless work, with no useful result other than to harass the rebels. Foote's morale collapsed again. His Donelson wound still refused to heal, and he was often feverish. He sent a request to Navy Secretary Gideon Welles to be transferred to shore duty, and it was granted with regret. On 9 May, he made his farewells. He took off his cap and said to the men assembled on his flagship that he was sorry he could not stay with them until the war was over. He would remember what they had shared "with mingled feelings of sorrow and pride."

He left the vessel for a transport with an officer on either arm to hold him up, and was seated on a chair. As the transport left, the men cheered, and Foote had to hide the tears running down his face. They cheered again and threw their caps in the air. Foote, overcome, rose and cried back at them: "God bless you all, my brave companions! ... I can never forget you! Never! Never! You are as gallant and noble men as ever fought in a glorious cause, and I shall remember you to my dying day!"

After returning from sick leave, Foote would be given soft shore duty assignments back East. He was replaced by Captain Charles Henry Davis, a 55-year-old Bostonian. On taking command, Davis considered his situation and found it dull, boring. That impression would prove dangerously misleading.

* Halleck's reorganization not only kicked Grant upstairs, it also merged Grant's Army of the Tennessee, Buell's Army of the Ohio, and Pope's Army of the Mississippi. Buell and Pope retained their commands, but there was a reshuffling of combat units and command assignments.

George Thomas had arrived with Buell's fifth division after the battle at Shiloh. He was now a major general as a reward for his victory at Logan's Crossroads. His division was shuffled from Buell's command to join the divisions that had reported to Grant, and Thomas was given effective command as a whole. Grant's useless position gave him oversight over Thomas in principle, but in practice Grant had no authority. John McClernand was assigned command of three reserve divisions, including his own division, one of Lew Wallace's, and a third taken from Buell. C.F. Smith was not part of the organization, since his infection from a scraped knee killed him before the month was out. Halleck ordered a salute fired at every post and on every warship in his command, and Grant grieved for the subordinate he had looked up to.

Halleck had, in total, 15 divisions with 120,000 men and 200 guns. Pope and Thomas were happy with their new positions. Buell, who was reduced to three divisions, and McClernand, who found being in command of a reserve unlikely to bring him much glory, were equally unhappy.

Halleck also had control over two divisions left behind when Buell had marched his other forces to Pittsburgh Landing. One, under Brigadier General George W. Morgan, was positioned in front of Cumberland Gap. Morgan wanted to move forward and seize Knoxville, but mud and mountains made it impossible in the face of Confederate forces, and his division stayed where it was.

The other division, under Brigadier General Ormsby M. Mitchel, was on the move and in fact was deep into Confederate territory. Mitchel's division took Huntsville, Alabama, on 11 April 1862, achieving complete surprise and the capture of 15 locomotives plus a large number of railroad cars, and then continued along a curving arc back up towards Chattanooga, Tennessee, the key to the mountain regions. If Mitchel could take Chattanooga, a central rail hub in the region, Knoxville would be open to an advance from the rear, and the Confederates would have to pull out. Morgan's division would then join hands with Mitchel's, and the rebels would be cleaned out of East Tennessee.

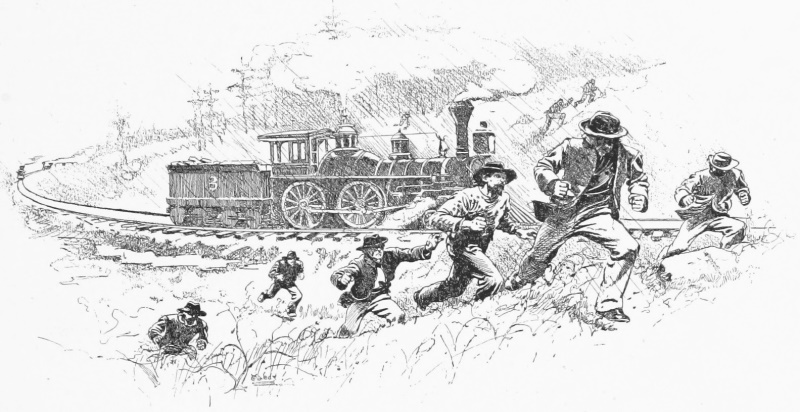

In order to achieve this, Mitchel enlisted the aid of James J. Andrews, a Kentuckian who had been running quinine to the rebels but who was in fact a Union spy. Mitchel wanted to wreck the Western and Atlantic Railroad, the only rail connection between Atlanta and Chattanooga, which would cut off Confederate reinforcements from Chattanooga. Andrews volunteered to lead a band of 21 Ohio soldiers dressed in civilian clothes to seize an engine and then proceed along the railroad, burning bridges and blowing up tunnels.

The men infiltrated south and assembled in Marietta, Georgia. On 12 April, they boarded a northbound train as passengers, and during the breakfast stop they made off with the engine, named the GENERAL, and three boxcars. The conductor, W.A. Fuller, was so infuriated that he set out after them on a handcar, then commandeered a switch engine, and finally took over a freight locomotive, gathering armed assistance as he proceeded north. He stayed so close on Andrews' tail that the Yankees had no time to do any serious damage. The GENERAL ran out of fuel and water north of the Tennessee line. Andrews and his men tried to escape through the woods, but were all captured. Andrews and seven others were hanged as spies, eight escaped, six were exchanged. Most got the Congressional Medal of Honor; Andrews didn't, because he was a civilian.

The Andrews raid was a great adventure story, but it was a military failure. The line to Chattanooga remained intact, and Mitchel was finding his military position uncomfortably precarious. Although he was loudly promoting his successes, even going so far as to send wires directly to Secretary of War Stanton, Mitchel was finding himself increasingly at risk of isolation deep in enemy territory. Beauregard had sent two columns of cavalry behind Union lines, one towards Paducah, Kentucky, and the other in Mitchel's rear. The raid towards Paducah fizzled because of bad leadership, but the second column, under John Hunt Morgan, now a colonel, raised hell on Mitchel's supply lines. Short on supplies to begin with, Mitchel ended his advance and pulled back into northern Alabama, destroying bridges and tearing up rail lines behind him.

Halleck, never the most decisive of commanders, was not encouraged by Mitchel's withdrawal. It made the capture of Corinth, Mississippi, a more difficult prospect, since for the moment the Confederates were undistracted elsewhere and could focus their attention on its defense. On 28 April, Halleck uneasily sent his army forward to capture Corinth.

BACK_TO_TOP* A Union naval force had captured New Orleans on 1 May. A ragtag Confederate fleet of eight steam rams, completely outmatched, fled upriver, docking at Memphis on 9 May. There, the scratch fleet's effective commander, J.E. Montgomery, held a council of war with the captains of the other vessels. The fall of New Orleans had left them angry, and fearful that they might be hemmed in by Union Navy forces coming from both upstream and downstream. However poor the odds, it seemed wisest to attack now instead of wait for the odds to get worse.

The next morning, Sunday 10 May 1862, the Union ironclad CINCINNATI was standing guard over MORTAR 10 while it tossed shells into Fort Pillow. The Union sailors weren't expecting a fight; the ship's steam was down and they were scouring the ship for weekly inspection. At about 7:00 AM, however, a lookout shouted in alarm and the crew saw the rebel rams turning the bend, about a mile away, giving the Federals about eight minutes to react.

The Union gunboats cast off and tried to build up steam by throwing anything that would burn into the furnace, but the Confederates came on them too quickly. The gunboat CINCINNATI fired a broadside at the lead ram, the GENERAL BRAGG, and managed to swing around to prevent the ram from striking her at a right angle. The resulting glancing blow still tore an opening 6 feet deep and 12 feet long (2 by 4 meters) in the CINCINNATI. A second ram, the SUMTER, collided with the CINCINNATI, followed by a blow from a third ram, the COLONEL LOVELL. The ironclad shuddered and went down in shallow water, her crew clinging to the pilot house.

The sailors of the Union fleet sitting idly upstream had no clue of what was happening until they heard the boom of cannons, and then set off downstream as fast as they could get their steam up, with the gunboat MOUND CITY leading the way. As it turned out, the MOUND CITY was a little too far in the lead: a fourth rebel ram, the GENERAL VAN DORN, smashed head-on into the Union gunboat. The ironclad managed to limp to the bank, to sink with her nose out of the water.

The Confederates had pushed their luck and gotten away with it, but they knew they couldn't get away with it much longer; they turned tail and went downstream to the protection of Fort Pillow. Montgomery led the scratch fleet back to Memphis to a rousing reception, reporting that if the Federal fleet remained at its present strength, it would "never penetrate farther down the Mississippi."

It was boldly done. With inferior weapons, the Confederates had taken the Yankees by surprise and bloodied them, made fools of them. Montgomery's confidence had some justification -- but he greatly over-estimated the strength of his position.

* Halleck had wanted to move quickly with his offensive into Mississippi against Corinth, but it was not in Halleck's nature to do anything very decisively. His anxieties soon began to get the better of him. The Confederates were in Corinth in numbers, and the numbers seemed to get bigger every time he thought about them.

On 3 May, he wired Washington to optimistically say his army would be "before Corinth tomorrow." John Pope moved ahead swiftly, reaching the next day a position 4 miles (6.4 kilometers) from Corinth that he felt was easily defensible, as long as he had support. That was as far as he got. Don Carlos Buell was moving slowly and could not protect Pope's flank, and before long Pope was forced to pull back under Confederate attacks. Beauregard sent his soldiers against the Yankees with a stirring speech: "Soldiers, can the result be doubtful? Shall we not drive back into Tennessee the presumptuous mercenaries collected for our subjugation?"

The weather turned wet and the roads turned to muck. Halleck reported that he would invest Corinth "in a few days". Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, untrusting by nature, did not fail to notice the fact that "tomorrow" had turned into "a few days". Halleck's fear grew to the extent that his men dug in for four hours each evening, followed by six hours of sleep, to wake up at dawn to repel potential attacks. Rebel deserters came through the lines and spoke of a massive troop buildup. In mid-May, pickets were reporting the arrival of trains in Corinth, greeted by "immense cheering". Estimates of Confederate strength grew to 200,000 men. The weather began to turn dry and hot, and the soldiers in their wool uniforms began to curse Halleck as they dug in every night. Some of Halleck's generals, including Pope, Thomas, and Sherman, grew exasperated. Grant was particularly frustrated. When he proposed a swift flanking movement into Corinth to Halleck, Grant was "silenced so quickly that I felt that possibly I had suggested an unmilitary movement."

The Federals moved slowly, but they still moved. By 28 May, the three components of Halleck's army were entrenched within range of the Confederate defenses, about 15 miles (24 kilometers) from where they had started a month before, and began their attacks on Beauregard's lines.

Halleck seemed not to have wondered why, if the Confederates were so powerful, they allowed him to move so close unmolested. Had he done so, he might have questioned the stories the rebel deserters were feeding him. In reality, many of these "deserters" had been sent out personally by Beauregard, after being carefully briefed with misinformation to feed the Yankees. Just to be on the safe side, Beauregard carefully leaked "plans" for an advance through his ranks, so that real deserters proved almost as misleading.

Beauregard was using the time generously given him by Halleck to dig in and dig in deep. Unlike the Federals, the rebels didn't have to shovel new earthworks every night. Confederate losses at Shiloh had been made good by the arrival of Van Dorn and other forces from Arkansas; Beauregard hoped that he might be able to maintain an effective defense, or even take on an exposed segment of Halleck's army.

It was a slim hope at best. Corinth was a dismal place, something like Cairo to the north where the Federals had spent such a miserable time -- but worse. The town had foul drinking water, inadequate facilities for supporting the large numbers of soldiers there, and only about 50,000 men were healthy enough to conduct its defense. The attacks against Pope early in the month inflicted no great damage except on Halleck's nerves, and renewed assaults when Pope moved forward again proved no more useful.

Beauregard had to face reality. He was hopelessly outnumbered, with an army full of sick men, in a place incapable of supporting them during a siege. On 25 May, with Halleck closing slowly in, Beauregard called a council of war with his generals. Bragg, Breckinridge, Hardee, Polk, Price, and Van Dorn were in attendance. Hardee read a statement outlining the army's options, concluding that the only thing they could do was try to fall south along their rail lifeline and hope the Yankees would let them get away. The proposal was reluctantly approved.

Beauregard was undoubtedly disappointed, but he began plans for withdrawal with his usual energy. On 28 May, the Federals men began bombarding the Confederate lines and probing for weak points. It was now time to go. While heavy equipment and the sick and wounded were evacuated by rail, the able-bodied men were issued three day's rations and ordered to prepare to attack. Only the top officers and those with a need-to-know were aware they were really getting ready to pull out. Meticulous plans were laid for removing the rest of the army as quickly as possible. As the Confederate rear guard withdrew, they were to destroy all the roadsigns to help confuse Federal pursuit.

The news of a planned assault against an overwhelming Federal force led a few faint-hearted rebels to desert. That served Beauregard's purposes as well, since the reports provided by these deserters put Halleck on the defensive. Meanwhile, on the next day, 29 May, Beauregard's soldiers were told the truth. They reacted with considerable relief, as well as ingenuity of their own, throwing together Quaker cannons and scarecrow soldiers. In fact, they found the game of deception good fun. A band played loudly up and down the lines. As darkness fell and soldiers began to leave, drummer boys kept countless fires burning from stockpiles of sticks left alongside them, while a train shuttled back and forth through town, blowing its whistle and getting loud cheers from a detachment of the loudest men Beauregard's officers could find. At 01:20 AM, Pope exciteably wired Halleck:

THE ENEMY IS REINFORCING HEAVILY BY TRAINS IN MY FRONT AND ON MY LEFT. THE CARS ARE RUNNING CONSTANTLY AND THE CHEERING IS IMMENSE EVERY TIME THEY UNLOAD IN FRONT OF ME. I HAVE NO DOUBT FROM ALL APPEARANCES THAT I SHALL BE ATTACKED IN HEAVY FORCE AT DAYLIGHT.

Halleck's army went on alert and braced for the shock. Nothing happened. About 4:00 AM, everything went dead quiet. Then at daybreak, the town beyond the Confederate entrenchments rocked with loud explosions that threw up billowing clouds of black smoke. Pope's men probed the enemy defenses and found them deserted, except for grinning dummies and other deceptions left behind.

Halleck belatedly ordered Pope to pursue the fleeing Confederates, which he did enthusiastically, if with little result. However, Beauregard had made a fool out of Halleck, and so Halleck was desperate to save face with his superiors. That led to misunderstandings of Pope's dispatches that gave Halleck the false impression that Pope was scoring major victories. Halleck reported to the War Department that 10,000 rebels and large stores of equipment had been captured, leading Secretary Stanton to reply: "The whole land will soon ring with applause at the achievement of your gallant army and its able and victorious commander."

Halleck certainly felt pleased at that, having had almost bloodlessly seized a major strategic objective. Nobody else was as much impressed, certainly not his own generals. The newspapers had a field day when the details became known, revealing the overblown claims as nonsense. Fortunately for Halleck, the papers blamed John Pope for the falsehoods, and Halleck, not very surprisingly, did nothing to correct them.

BACK_TO_TOP* If the seizure of Corinth, Mississippi, seemed like a non-event, it still had major strategic implications. Corinth was a rail hub and the Federal army of 100,000 men could move from there in almost any direction against Confederate forces in the region, which included Beauregard and his army of 50,000 men in Tupelo, Mississippi; Major General Edmund Kirby Smith in Knoxville, Tennessee, with 12,000 men; or the 2,000 rebels in Chattanooga, Tennessee. These and a number of scattered smaller forces were all the Confederacy had in the region to oppose Halleck. Fort Pillow was now hopelessly isolated, and Beauregard ordered it and lesser works further downstream evacuated on 4 June, leaving Memphis defenseless,

J.E. Montgomery and the captains of the eight Confederate rams docked at Memphis were proud of themselves for sinking two Federal ironclads upriver of Fort Pillow in May, and believed they had taught the Yankees a lesson. They were thoroughly mistaken: they had simply made the Yankees mad.

The Federals chose a particularly ironic tool for getting their revenge: steam rams of their own, the creation of a 51-year-old engineer from Pennsylvania named Charles Ellet JR. Ellet had bombarded the government since the beginning of the war with various ideas. He was particularly obsessed with his proposal for ram warships, so much so that one naval officer said that after a time Ellet "had nearly gone insane on the ram question and had written and besieged the departments in Washington until they nearly went insane, too."

It wasn't until March 1862, after the beating dealt to the wooden warships blockading Hampton Roads by the CSS VIRGINIA, that Secretary Stanton took a personal interest in Ellet's rams. Stanton made him a colonel, and told him to build as many of the rams as needed to clear the rebels off the Mississippi. Ellet purchased nine steamers and converted them into rams in 50 days. They joined the Union fleet above Fort Pillow on 25 May.

Ellet's rams were very different from their Confederate counterparts downstream. Ellet regarded iron beaks as ineffective, and designed his vessels to destroy through sheer momentum. The rams carried no guns and no armor. The main weapon of each was simply a powerful steam engine, solidly mounted to stay in place even under heavy shocks, driving a hull reinforced at the prow with timbers and braced by three solid beams running the length of the vessel. These vessels were capable of 15 knots (28 KPH), making them the fastest ships on the river. They were potentially very effective in river warfare, where there was little room for maneuver.

Ellet's fleet had strong unity of command, since the captains of the rams were all Ellets. Seven of them were nephews and brothers, and one was his 19-year-old son. They had been all for steaming downstream and pitching into the rebels immediately, but Flag Officer Davis was cautious. Although he had raised the CINCINNATI and the MOUND CITY, three of his seven gunboats had gone upriver for repairs and Davis didn't feel ready to take on the Confederates. Ellet wanted to go ahead anyway, but could not get Davis to consent.

Although the Confederates in Memphis heard about the new vessels, they remained complacent, assuming they were merely transports. The rebels were also working on two monster ironclads, the ARKANSAS -- which had been launched, partly armored, and then towed south to be completed -- and the TENNESSEE -- which had neither been launched nor armored. If these two ironclads were completed, the rebels felt they would have the means to deal with the Federals on the river.

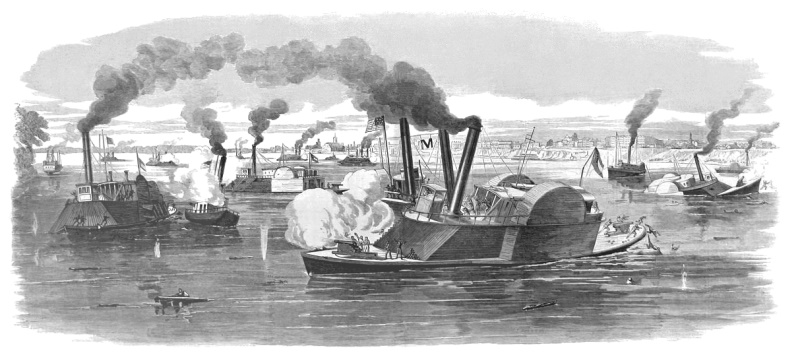

The evacuation of Fort Pillow removed the major obstacle to a Union attack on Memphis. Davis and Ellet finally came to an agreement, and on 6 June four Union ironclad gunboats came around a bend in the river towards the city, followed by four of Ellet's rams. The eight Confederate rams steamed out to meet them, watched by an audience of tens of thousands who lined the banks, expecting to see the Yankees take another beating. When the first shot was fired Ellet, on the ram QUEEN OF THE WEST, waved his hat to attract the attention of his brother on the ram MONARCH, and shouted: "Round out and follow me! Now is our chance!"

The two rams surged forward between the ironclads, whose crews cheered as they steamed past. The QUEEN OF THE WEST bore down on the COLONEL LOVELL at the head of the Confederate line; when the rebel ship turned to avoid a head-on collision, the Union ram struck the enemy ship amidships, almost cutting her in half, with the COLONEL LOVELL sinking immediately. Despite its heavy reinforcements, QUEEN OF THE WEST took considerable damage herself from the collision.

The MONARCH charged the GENERAL PRICE. When the BEAUREGARD tried to intercept, the Union ram slipped between the two rebel vessels, which then collided. The GENERAL PRICE lost a sidewheel and her captain beached the vessel. The MONARCH turned sharply and rammed the BEAUREGARD, which took a shell from one of the ironclads in her engine at the same time. The BEAUREGARD's captain surrendered the ship.

The Confederate ram LITTLE REBEL was destroyed by the ironclads; the rest of the rebel ships decided to turn around to run for it, but only the VAN DORN escaped. In a two-hour battle, the Federals destroyed three of the Confederate rams and captured four, which they would turn to their own use. The only casualty among the Federals was Ellet, who was wounded in the knee by a pistol shot. The many Confederates killed included Montgomery himself.

Powder smoke had shrouded the fight from the watchers on the banks, but it was obvious when smokestack after smokestack disappeared who was winning and who was losing. The crowd wailed. Things went quiet and the smoke cleared, revealing the utter defeat of the Confederate rams. There was nothing to do but set the TENNESSEE on fire and wait for the Yankees to arrive, which they did soon, in the form of a rowboat carrying Ellet's 19-year-old son and three seamen, who hoisted the Stars & Stripes over the post office. Two US Army regiments arrived later to secure the city. Ellet's wound was not considered serious -- but in that climate, as C.F. Smith had proved, even a scrape was potentially lethal, and Ellet died two weeks later of an infection. Two weeks after that, his wife, Ellie, worn out by grief, followed him to the grave.

* The news of continued Confederate military reverses was an embarrassment to Beauregard. Jefferson Davis was furious that Corinth had been given up without a fight. Beauregard replied to Davis's icy queries over the matter with all the formality he could muster, pointing out his subordinates had approved the withdrawal and that it was done in a professional fashion. It was, Beauregard said to an aide, the equivalent of a "brilliant victory".

Beauregard had other problems besides Richmond's disapproval. His health had been poor all spring, and his doctors had been telling him to take a rest. With his troops settled at Tupelo, a far healthier place than Corinth, he figured he could recuperate at Bladon Springs, in southern Alabama, and leave Braxton Bragg in charge. Beauregard was getting ready to leave when on 14 June he learned to his surprise that Bragg had been summarily ordered to command the defenses of Vicksburg. Beauregard wired Richmond, saying that Bragg would be needed with the army since Beauregard was going on a short sick leave. Then, realizing that he had not justified his leave to the War Department, as an afterthought wrote a letter describing his condition, posted it by mail, and went south.

Bragg was in a touchy situation and immediately wired Richmond for clarification. He received an answer immediately. He was assigned to permanent command, while Beauregard was relieved of duty. Bragg wired Mobile to alert Beauregard of the change, who replied with as much grace as he could. He was still bitter, and wrote a close friend to describe Jefferson Davis as "that Individual ... That living specimen of gall and hatred."

Cumberland Gap was evacuated the same day Beauregard was relieved. It seemed as though the Federals were now poised to push deep into the Confederacy. In reality, the Union had run out of steam in the West, for the time being. The war on the Mississippi went quiet for the time being.

BACK_TO_TOP* This document was derived from a history of the American Civil War that was originally released online in 2003, and updated to 2019. It was a very large document, and I first tried to simply break it into volumes for publication in ebook format; however, that proved unsatisfactory, and I decided to rewrite components of it to tell the story of famous battles and such. This stand-alone document was initially released in 2022.

* Sources:

* Illustrations credits:

Maps are the work of the author. Finally, I need to thank readers for their interest in my work, and welcome any useful feedback.

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 mar 22 v1.0.1 / 01 feb 24 / Review & polish.BACK_TO_TOP