* In February 1862, Ulysses Grant moved south in force, driving on Forts Henry and Donelson, the linchpins of the Confederate defense of Kentucky in the west. Fort Henry fell easily; Fort Donelson was tougher to crack, but it fell in turn, with Grant becoming the Union's hero. Nashville, Tennessee, soon fell to the Union; in the meantime, Union Brigadier General John Pope moved against the Confederate fortifications at Island Number 10 on the Mississippi, which obstructed Federal movement south on the river.

* The rebels weren't completely surprised by Federal aggressiveness, though they still weren't well-prepared for it. The Union probes that had been sent forward in January against Confederate defenses in the region had alerted Albert Sidney Johnston that the Federals were getting ready to move against him. Forts Henry and Donelson were the most critical, and so most logical, of targets. If the Federals took the two forts, the entire rebel defense of Tennessee would fall apart.

The previous fall Johnston had sent an engineer, Brigadier General Lloyd Tilghman, to take command of the forts and do what he could to improve them. Tilghman had arrived in late November to find the forts in a wretched state, lacking every necessity for an effective defense. Worse yet, Fort Henry had been built on low-lying ground where it was not only subject to flooding, but dominated by high ground across the Tennessee, on the west bank.

Tilghman screamed for reinforcements, and by mid-January, he had 5,700 troops at the two forts. After the defeat at Logan's Crossroads, Johnston placed more forces in positions where they could move to assist if need be. These reserve forces were under the command of Generals Gideon Pillow, Simon Bolivar Buckner, and John B. Floyd -- who had earlier played a dubious role in the defeat of Confederate forces in western Virginia.

Johnston was, however, astonished to find that, for whatever reasons, Tilghman had failed to take the obvious step of fortifying the heights across the river from Fort Henry, and in fact had discovered that Tilghman had not been able to make up his mind to do much of anything in particular. Johnston immediately wired Tilghman and ordered him to do dig in on the heights:

DO NOT WASTE A MOMENT. WORK ALL NIGHT.

* In the predawn twilight of 4 February 1862, the Union river fleet approached Fort Henry and left Grant with the question of where to put his troops ashore. There was a creek about three miles (five kilometers) north of the fort. Grant did not want his men to have to ford it, but he was concerned that landing closer to the fort would put them in range of rebel guns. Grant halted the fleet eight miles (13 kilometers) short of the fort and sent three of the ironclads forward to draw fire from the fort's guns. He boarded the little ESSEX to get a first-hand view of the situation.

The ironclads got within two miles (three kilometers) of the fort, and then started trading shots with the rebels. A Confederate six-inch (9.6-centimeter) gun went into action, giving Grant the information he needed by overshooting the vessels and splashing a shot beyond the mouth of the creek. The gun then emphasized the lesson by slamming a cannonball into the ESSEX. The three ironclads turned around, and went back downriver to the transports.

Grant unloaded his First Division north of the creek and sent the transports back downriver to bring back his Second Division while he planned his attack. He quickly grasped the importance of the high ground across the river from the fort that had so worried Johnston; the beating Grant and his men had taken at Belmont from rebel guns on high ground had burned that particular lesson into his brain. Grant decided that most of the Second Division would move forward, seize that high ground and plant artillery batteries there, while the First Division would attack the fort directly from the east.

The rebels had added a new factor to the equation of battle: "torpedoes", they called them. Today we would refer to them as "mines"; they were cylinders of explosives, anchored to the river bottom, carrying long rods that in principle would set off the charge when a ship brushed against them. The river was rising from the winter rains, tearing the torpedoes from their moorings or leaving them too deep to be effective, but they were still a worry.

On the afternoon of 5 February, during a conference between Grant, Foote, and the two division commanders, the captain of a gunboat sent a message to Grant that he had pulled a torpedo out of the river and had it on the gunboat's deck; would anyone care to see it? Since the Second Division was still being shuttled in to the landing and the attack could not go forward until they arrived, leaving Grant and the other senior officers with little to do for the moment, they went over in a group to investigate.

The officers gathered around the torpedo, which was a five-foot (1.5-meter) long cylinder with a pronged rod extending from its head. Grant was intrigued by the evil-looking thing, had the ship's armorer come up to try to dismantle it, and watched as the man tinkered with the device. Suddenly, as the armorer loosened a nut, the torpedo emitted a loud hissing sound that appeared to be building to an explosion. The men scattered, with Foote climbing up the ship's rope ladder and Grant close behind him.

The hissing died out, leaving the two men hanging on the ladder. Foote looked down to see Grant beneath and, smiling, asked: "General, why this haste?" Grant replied: "That the Navy may not get ahead of us."

* Tilghman was outnumbered almost 5-to-1; his men were poorly armed; and the winter rains were raising the river level, threatening to flood the rebels out. He wanted to make a fight of it at first and wired for reinforcements, but as the Federal buildup continued, he realized his position was hopeless. He ordered most of the men to march to Fort Donelson, and stayed behind with a skeleton force in order to at least offer token resistance to the Federals.

Grant and Foote moved against the fort at midday on 6 February. While the soldiers moved to prepare a ground assault, Foote's gunboats closed on the fort and began to blast away at it. The rebels fired back, striking Foote's flagship 32 times and punching a hole in the ESSEX's boiler, leaving her powerless with scalding steam strewing dead and dying men on her gun deck. 32 of her men were casualties. However, the Confederates had only two cannon capable of damaging the ironclads; one soon burst while firing, and the second was put out of action by a broken priming wire. The defenders' position grew steadily more difficult.

Tilghman had asked his men to hold out for an hour to give those who had left time to make good their escape, and the fort had held out for two; he decided they had done well enough, and surrendered. It was hardly a hard-fought victory for the Union. There were a few dozen casualties on each side, the Federal ground forces had never got into action, and the fort was flooded by evening anyway, making the whole fight a little pointless. Grant was still pleased, since now the Tennessee River was an open road. He took immediate advantage of it. The three wooden gunboats were sent to destroy the railroad bridge 15 miles (24 kilometers) upstream, severing the connection between Bowling Green and Memphis. The gunboats continued upriver, 150 miles (240 kilometers) in all, to Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where they destroyed or captured six rebel vessels.

Fort Henry was only half the job, however. There was still the problem of Fort Donelson. Albert Sidney Johnston was certain that Fort Donelson would be attacked immediately. He telegraphed Richmond from his headquarters in Bowling Green on 7 February to inform his superiors that Fort Henry had fallen and Fort Donelson was "not long tenable". Worse, Buell was closing in slowly on Bowling Green with 40,000 men to confront the 14,000 rebels there. Buell had been just as goaded by Grant's action at Fort Henry as Halleck had been by Thomas's victory at Logan's Crossroads. The Federals had cut Johnston's connection to Memphis, and once the Yankees took Fort Donelson, they would be able to steam up the Cumberland and seize Nashville, Johnston's base of supplies.

Johnston could not stay where he was. He held a council of war on that day with Hardee and Beauregard, who had just arrived in Kentucky. The 15 Confederate regiments that had put fright into Halleck had not arrived with Beauregard, since they didn't really exist. On arrival, Beauregard had expected to find a powerful military machine in operation that could deal the Federals strong blows, and was shocked to find out that the great Confederate armies of the West were only a propaganda mirage.

By the time Beauregard was called to the meeting, he had recovered from his shock. Beauregard, not one to think small, advocated that Johnston throw everything he had at Grant, and then turn on Buell. The level-headed Johnston decided against it. He had the military sense to understand his position was impossible; the only thing to do was abandon Kentucky completely to the Federals and pull back behind the Cumberland. The garrison at Fort Donelson was ordered to hold off Grant and his men as long as possible to buy time, then escape when they could take no more. On 11 February, Johnston began the withdrawal from Bowling Green. Beauregard was ordered to Columbus, Kentucky, to evaluate the situation in the now-isolated town and withdraw the Confederate forces there if he judged it necessary.

BACK_TO_TOP* Grant could have attacked Fort Donelson immediately after taking Fort Henry, but he had looked over the Confederate defenses; he decided to wait for Foote's ironclads to steam back down the Tennessee and then up the Cumberland to support him. Besides, Halleck was sending Grant every man he could scrape up, and so Grant felt he could afford to wait.

On 12 February 1862, the day after Albert Sidney Johnston began to pull out of Bowling Green, Grant's men began their overland march from Fort Henry to Fort Donelson. Grant had 15,000 men in his column, with 2,500 left in reserve at Fort Henry and another 10,000 moving up the Cumberland on transports. The weather was sunny and pleasant. Many of the green troops discarded their bulky winter overcoats and extra blankets by the roadside.

Grant's decision to wait proved an error. Having had an easy victory at Fort Henry, he assumed the same would be true at Fort Donelson, but Confederate reinforcements had been trickling into Fort Donelson in the meantime. The first arrivals were the refugees from Fort Henry on 7 February, then General Gideon Pillow and his men on the 9th, followed by Simon Bolivar Buckner's force on the 10th. By the time Grant moved out, the fort was heavily garrisoned, and it was also relatively well-built and well-sited. Heavy guns were competently dug in on high ground overlooking the Cumberland, and land approaches were controlled by trenchworks that made effective use of the terrain.

The Federal column arrived at Fort Donelson at midday on the 12th, to run into sharpshooter fire. Cannon fire booming from the Cumberland in front of them indicated that naval reinforcements had arrived as well. It turned out to be a solitary gunboat, the CARONDELET. The other vessels were still downriver, but the naval support was welcome. The rest of the day was spent investing the fort. Grant's Second Division, under C.F. Smith, moved to cover the northern approaches to the fort, while the First Division, under John A. McClernand, moved to cover the southern half.

Real fighting started immediately after dawn on 13 February. John McClernand was an ambitious but militarily-inexperienced Illinois congressman who had taken a brigadier general's rank to get his share of glory. He quickly sent a brigade forward to silence an annoying Confederate battery. It was an artless attack, the battery proved strong, and after three rash charges the Federals called it quits, leaving their dead and wounded on the field.

The CARONDELET then joined in the fight, while C.F. Smith sent one of his brigades forward. The Union soldiers made a little headway, but the only result was that they were left in the open in the face of murderous Confederate sharpshooter fire. By the end of the day, they had been forced to withdraw. The CARONDELET had fired hundreds of rounds at the fort, to no great effect; the ironclad had been hit twice in return, with one cannonball penetrating into the engine room and bounding about "like a wild beast pursuing its prey". The ironclad had made emergency repairs and then continued the bombardment through the rest of the ground attack.

Grant was not particularly disturbed by the bloodying. It demonstrated that the rebels were willing to stand and fight and were well dug in, but Grant knew he would be able to crack them anyway once his water-borne reinforcements arrived.

Additional Confederate forces under John B. Floyd had arrived at Donelson that day to help oppose Grant's attacks, and Floyd took command of the fort. There were now 17,500 men inside Fort Donelson, and for the moment there were more rebels inside the fort than Federals outside of it. The balance would quickly tip back against the Confederates. Why Albert Sidney Johnston allowed reinforcements to be sent in when he had no intention of holding Fort Donelson is hard to understand. It was also hard to understand why he assigned the command to Floyd, who had proven his incompetence in the mountains of western Virginia. In addition, Pillow was a questionable choice as his second-in-command; he had achieved some notoriety in the Mexican War by having his men entrench with their line facing away from the enemy. Such decisions hint that Johnston's inspiring martial bearing did not quite match his actual combat capabilities.

Grant's soldiers were as confident as their general until dusk, when a cold rain began to fall. The weather grew colder and more miserable, dropping to 10 degrees Fahrenheit (-12 degrees Celsius), leaving everything coated in ice, making the men thoroughly wretched. The soldiers who had discarded their winter gear on the march from Fort Henry now regretted their hasty decision. By morning, there were two inches (five centimeters) of snow on the ground.

Snow or not, Grant was going to smash the rebels. During the night he had ordered his 2,500-man reserve at Fort Henry to march over immediately, and in the morning Foote arrived with his gunboats and 10,000 reinforcements. Grant reshuffled the troops in place and used the reinforcements to constitute a Third Division, under the command of Brigadier General Lew Wallace, a 34-year-old ex-lawyer from Indiana, and put the new division into the center of the Union line. Grant's plan was simple: his soldiers would ring in the Confederates, and then Foote's gunboats would bombard Fort Donelson into submission. Foote had four ironclads, including his flagship the SAINT LOUIS, the CARONDELET, the PITTSBURGH, and the LOUISVILLE, plus two of the timberclads, the TYLER and CONESTOGA. Foote had wanted more time to prepare for attacking the fort, but he liked Grant's willingness to press the enemy, and so at 3:00 PM on 14 February, Foote went up the river to the fort.

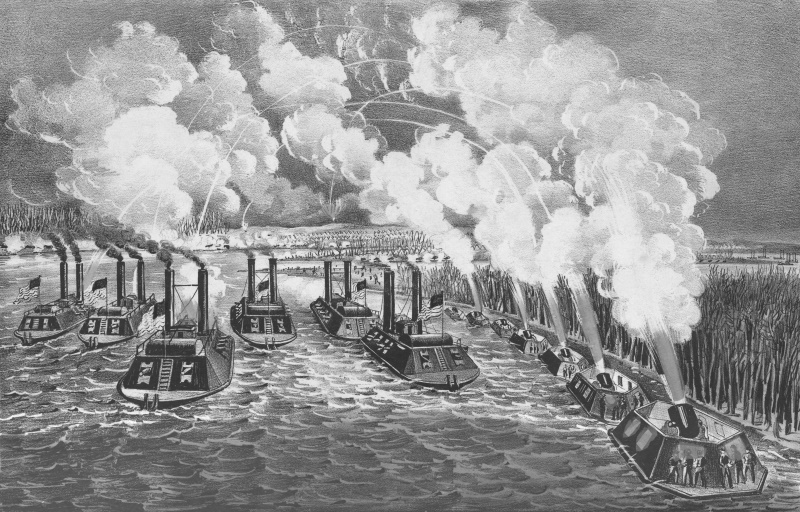

The ugly ironclads led the way, four abreast, followed by the two wooden gunboats. The Confederate batteries opened up when the ships were a mile and a half (two and a half kilometers) away, while the gunboats waited until they were a mile (one and a half kilometers) away from the fort and opened fire. As Foote closed in on the fort, the fire between attackers and defenders grew more intense. Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest -- a man who liked to fight, was skilled at it, and notably hard to intimidate -- was moved to call out to one of his officers, who had been a preacher: "Parson, for God's sake pray! Nothing but God Almighty can save this fort!"

In fact, as Foote's ships approached to within a quarter-mile (400 meters) of the fort, Foote could see rebels gunners fleeing from the fort's lower batteries, and believed that in 15 minutes they would shut down the batteries. Unfortunately for Foote, the Confederate fire was also proving more effective at close range, tearing off armor from the gunboats, smashing lifeboats and smokestacks. Just as Foote thought he was winning, a solid shot smashed into the SAINT LOUIS, tearing away the wheel, killing the pilot, and wounding Foote along with everybody else in the pilot house, except for a nimble reporter who had been recording the battle.

The SAINT LOUIS drifted around in the current and fell back downstream. The PITTSBURGH, having had its tiller ropes shot away, followed her. The LOUISVILLE took hits near the waterline and then lost her steering gear as well. The CARONDELET, taking on water from hits near her bow, turned about and fled, firing wildly in order to conceal itself in its own smoke. That was the end of the attack. The Federals had taken 54 casualties, including 11 killed outright. The Confederates hadn't lost a single man and were jubilant. Grant had to disappointedly report back to Halleck:

APPEARANCES INDICATE NOW WE WILL HAVE A PROTRACTED SIEGE HERE.

If that was what it would take, that is what would be done.

* Confederate General John B. Floyd was doubly pleased at bloodying the Federals. Not only had he driven off Foote's seemingly-invincible ironclad monsters, he had held off Grant long enough to allow the rebel forces under Albert Sidney Johnston and Hardee to complete their evacuation from Bowling Green. Their men were now safely in Nashville, or on the way there. The next trick Floyd had to pull off was to break out of Fort Donelson, and join Johnston in Nashville. He had no good reason to stay any longer.

Floyd had planned the breakout on the 14th, but Foote's ironclads had distracted him. After the fight, he called a council of war to consider what to do next. Floyd, an amateur, took his counsel from two professionals, Gideon Pillow and Simon Bolivar Buckner. Unfortunately, the counsel could not have been more divided, short of coming to blows. Pillow was exciteable, enthusiastic, willing to take on anybody, while Buckner was gloomy and cautious. Furthermore, the two men had been enemies back to the Mexican War. Floyd had demonstrated indecisive leadership as well as a tendency to fumble under pressure in the mountains of West Virginia; contradictory advice was the last thing he needed.

Despite all that, Floyd decided that they would attempt the breakout at dawn on 15 February, striking through McClernand's First Division on the southern part of their perimeter, and the Confederates worked all night to prepare their assault. It was miserable work, since there was a snowstorm in progress, but the storm concealed their actions from the Yankees, who were busy trying to deal with the cold.

The rebels also had another piece of good luck. Grant left his headquarters before dawn to confer with Flag Officer Foote, who was retiring downriver with his wounds and damaged ironclads and wanted to speak with Grant before he departed. On leaving for the meeting, Grant had given orders that his division commanders stay put and do nothing to provoke an engagement, later admitting that it had never occurred to him that the rebels might take action themselves. He left no one in charge.

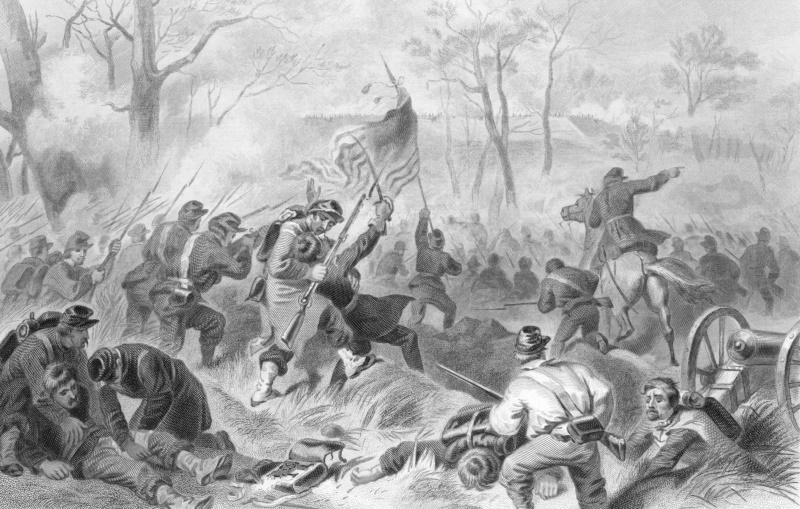

The Confederate attack went forward as planned, with Forrest's cavalrymen leading the way. The Federals were not completely unprepared, since it was too cold to sleep and most of them were up and about at dawn to light fires to keep warm. They fought back stubbornly but were hard pressed. McClernand asked Lew Wallace for assistance; unfortunately, in Grant's absence, nobody at headquarters was willing to take responsibility for serious decisions.

After three hours of fighting, McClernand's men ran low on ammunition and began to give way in panic. Wallace, watching the stream of panicky men coming into his position, detached two brigades on his own authority to try to stem the disaster. The rebels were on the edge of winning the battle, but at that moment, the confusion in the Confederate command asserted itself. Ironically, Pillow suddenly became fearful of a counterstroke while Buckner insisted on pressing forward. Floyd showed up and found himself forced to settle the dispute. At first he agreed with Buckner, but Pillow took Floyd aside and thoroughly discouraged him. Floyd ordered the men back into the fort's perimeter. The Confederates had almost won, and then threw it all away.

Grant didn't hear of the fighting until about noon; he was returning to his command when he met a panicky captain on the road. Grant spurred his horse, but it took him another hour to get to his lines, where he found Wallace and McClernand bickering angrily with each other. Grant cooly took charge and began to restore order. The situation was tense, but not out completely out of control. McClernand's soldiers had taken a beating and were disorganized and dispirited -- however, Wallace's men, though excited, were hardly panicked, and Smith's troops were calm.

Grant correctly interpreted the Confederate attack as an attempt to break out of the fort, and realized that the failure to achieve the breakout had probably demoralized them. If he attacked immediately, he might be able to break them. He told McClernand's men: "Fill your cartridge boxes, quick, and get into line. The enemy is trying to escape and he must not be permitted to do so." The soldiers did not balk. Having become disoriented, it was a relief to get some clear direction, and they prepared to take up the fight again.

Grant sent word to Foote to use his operational gunboats to make a demonstration, not with any intent to cause real damage, but simply to bolster the morale of the attackers, and undermine that of the defenders. Then he rode to the north end of the line and ordered C.F. Smith to charge the rebels. Grant had also correctly calculated that the rebels had stripped their northern entrenchments to support their breakout attempt, and told the old general that he would find only "a very thin line to contend with." Smith replied: "I will do it!" -- and was on the offensive almost immediately. Smith was 60 years of age, ancient for a front-line soldier, with a great white mustache, and looked inspiring as he rode out in front of his men to lead them to the Confederate defenses. He shouted out to his troops: "Damn you, gentlemen! I see skulkers, I'll have none here!"

The Federals drove back the rebel regiment that had been holding the line and seized a ridge overlooking the fort. To the south, McClernand and Wallace drove the rebels back into their lines, while two ironclads tossed shells into the fort from long range to help add to the confusion. As long as the Federals held the ridge, they could bring all the Confederate defenses under bombardment. The fort had effectively been lost and Floyd and his generals knew it. That evening Floyd held another council of war in which Pillow and Buckner angrily traded accusations, while the befuddled Floyd was caught in the middle.

Forrest had been scouting and found an escape route, a road that skirted the river to the south, but it was flooded by a swollen creek at one point. The army surgeon worried that fording the icy water might be fatal to some of the troops crossing it. Floyd's demoralization reached the breaking point when he was given a report that Grant had received another 10,000 men. As Floyd already believed he was outnumbered 4 to 1, he felt he had no alternative but to surrender.

Neither Floyd nor Pillow personally wanted to be the ones to surrender to the Federals. Floyd had been President Buchanan's Secretary of War, and had taken suspicious actions in that capacity before he went South; he feared he might be brought up on treason charges. As for Pillow, he was too fiery to submit to any such humiliation. Command was passed to Buckner, who had been friendly with Grant before the war and might be able to obtain better terms. Forrest was rightly infuriated with the whole farce, angrily standing up to declare: "I did not come here for the purpose of surrendering my command!" Buckner agreed that Forrest could lead his troops out of the fort if he started before surrender negotiations got under way, and Forrest stomped out fuming into the night, followed by Floyd and Pillow.

Buckner sat down and wrote a note to Grant, proposing a cease-fire while the two sides discussed terms. Buckner sent a messenger with his letter and a flag of truce through the lines into Smith's Second Division. The messenger had trouble getting through the lines, since the rebel soldiers themselves were by no means ready to give up, but he managed to make his way to C.F. Smith and hand over the message. Smith rode to the farmhouse where Grant had set up his headquarters and found him warm in a feather bed; Smith gave him the letter, saying: "There's something for you to read."

Grant read the letter and laughed, asking Smith: "Well, what do you think of it?" Smith replied: "I think, no terms with traitors, by God!" Grant took a tablet and quickly wrote up a response:

Hd Qrs. Army in the Field Camp near Donelson, Feb 16th Gen. S.B. Buckner, Confed. Army, Sir: Yours of this date proposing Armistice, and appointment of Commissioners, to settle terms of Capitulation is just received. No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately on your works. I am Sir: very respectfully Your obt. sevt. U.S. GRANT Brig. Gen.

He handed the letter to Smith, who read it in the firelight and said: "By God, it couldn't be better!" The message was sent back to Buckner.

While this had been going on, a Confederate steamboat had arrived in the night with 400 reinforcements, just in time for them all to be taken prisoner. Floyd commandeered the vessel for his own brigade, which consisted of four Virginia regiments and one Mississippi regiment. He got two of the Virginia regiments across the Cumberland and was loading up the other two when word from Buckner arrived that since surrender negotiations had begun, those who did not leave at once would have to remain to be given up to the Federals. Floyd hurried on board and ordered the vessel to shove off, leaving the Mississippi regiment behind, howling in protest.

Pillow was only able to find an old scow and run away across the river with his chief of staff. The rest of his command remained behind to be captured. Forrest, however, got away not only with all his own men, but also with a number of infantrymen who doubled up with the cavalry troopers on their horses over the flooded stretches of the road.

Buckner was distressed by the "ungenerous and unchivalrous" terms of Grant's response, but knew he had to capitulate anyway. At sunup, on Sunday, 16 February 1862, he and his officers shared a friendly breakfast with Grant and some of his lieutenants. The surrender took place without formality or even much military diligence, and many Confederates simply walked away unhindered. Grant didn't seem to care much.

In fact, as he told Buckner, he was more than happy to see Gideon Pillow get away: "If I had captured him, I would have turned him loose. I would rather have him in command of you fellows than as a prisoner." The Federals had more mixed feelings about the escape of Floyd: he was at least as inept as Pillow, but he was indeed wanted on criminal charges in the North for fraud and treason. Buckner had loaned Grant money in 1854 when Grant was broke and down, and so Grant was not insensitive to Buckner's distress. Grant offered him the use of his purse.

BACK_TO_TOP* On 15 February 1862, the same day the issue was decided at Fort Donelson, General Beauregard left Nashville for Columbus, Kentucky, taking a train by a roundabout connection through the rail hub at Corinth, in northwestern Mississippi. He only made it halfway northwards back towards his destination, falling sick with a severe sore throat and taking shelter in a hotel in Jackson, Tennessee. He ordered General Polk to come south from his command in Columbus. When Polk arrived, Beauregard, ill and depressed, told him that Columbus had to be abandoned.

Polk protested, saying he had been fortifying Columbus for five months. Beauregard sadly replied that the manpower could not be spared, and Polk's 17,000 troops would have to fall back to New Madrid, Missouri, 40 miles (64 kilometers) downstream from Columbus, near the Tennessee border line. There, the swampy terrain could be defended by half of Polk's forces, leaving the remainder to plug the gaping hole in the center of the Confederate line of defense. Columbus was isolated now anyway, with any force that remained there being in danger of being cut off and captured.

Polk returned to Columbus and, now as depressed as Beauregard, began his withdrawal. If he could not stand and fight, he would at least make sure that everything he had went with him as he retreated. Despite an attack by Federal gunboats on 23 February and the logistical difficulty of moving 140 guns, 17,000 men, and all their camp equipment, Columbus was empty of Confederate troops and equipment by 2 March. 7,000 men went to New Madrid, while the remaining 10,000 moved south to the rail hub at Humboldt, Tennessee, halfway to Corinth, where they could be moved to reinforce threatened points along the Confederate line.

The Federals had won a great victory at Fort Donelson. Although they had suffered 2,000 casualties, they had captured roughly 14,000 rebels and torn the Confederate line in Tennessee wide open. Church bells rang across the North at the news of the victory, and "Unconditional Surrender" Grant was the hero of the hour. The various defects of his conduct of the campaign went unnoticed; what counted was that he wanted to fight, and fought until he got what he wanted. While his delay in starting the attack on Fort Donelson had resulted in the Confederates concentrating a large force against him, through his luck and the incompetence of rebel leadership the end result was that he had dragged in a bigger haul.

The bells rang in Nashville that Sunday as well, but not to celebrate. Instead, they rang to warn the populace that the city would soon fall to the Yankees. Albert Sidney Johnston put his forces on the road to regroup in Murfreesboro, not far to the south, and the citizenry panicked as the troops pulled out. There was a flood of people trying to save their possessions and get out of town.

Johnston had accumulated massive stockpiles of stores in Nashville and wanted to save as much of them as he could before the Federals arrived. When Floyd arrived on Monday, he was put in charge of removing the supplies, a task complicated by the disorder of the citizenry who had fallen to looting. When Forrest arrived from Fort Donelson on Wednesday, the cavalryman was ordered to assist. Floyd decided to leave the work to Forrest and marched his brigade out of the city on Thursday morning. This was just as well, since it left Forrest free to pursue the removal of the supplies with great efficiency, sending South badly-needed industrial gear and trainloads of bacon, flour, ammunition, clothes, and other stores.

In order to placate the public, the mayor had promised they could take whatever was left of the stores when the Confederate Army finally pulled out, but it quickly became clear that the efficient Forrest would leave little behind. A mob tried to block Forrest's men; he tried to appeal to their patriotism, but failing in that, he set his troopers onto the crowds to disperse them with the flat of their sabers. Fire hoses spraying ice-cold river water were also used at one warehouse, with "a magical effect".

Forrest stayed in Nashville into Sunday, three days longer than he had been ordered, and only withdrew down the road to Murfreesboro when Federal soldiers appeared on the north bank of the Cumberland. As it turned out, the Union men were merely an advance party of Buell's command; a surprised captain accepted the surrender of the city. Buell's forces didn't arrive in strength until Tuesday, 25 February 1862, to find the city deserted and shut up. The Union high command was in some ways as taken unawares by Grant's victory as the Confederates were by their defeat, and so the Federals did not move aggressively.

The Confederates had completely lost their hold on Kentucky, and the Federals had made great inroads into Tennessee. The failures of leadership at Fort Donelson had been a painful humiliation. Grant regarded Pillow and Floyd as inept; Confederate leadership came to the same conclusion, and both were put on the shelf, to do no more harm. Albert Sidney Johnston was fiercely criticized, but made no excuses, writing Jefferson Davis: "I observed silence, as it seemed to me the best way to serve the cause and country." Davis, who was unswervingly loyal, replied: "My confidence in you has never wavered, and I hope the public will soon give me credit for judgement rather than to continue to arraign me for obstinacy."

The complaints increased, and at one point a delegation called on Davis to demand Johnston's dismissal, saying he was no general. Davis stood up and replied icily: "If Sidney Johnston is not a general, we had better give up the war, for we have no general." He showed his visitors the door.

* Although Grant had won a major victory for the Union at Forts Henry and Donelson, he was finding out that no good deed goes unpunished. Grant had received a promotion to major general, on the recommendation of his boss, General Henry Halleck. However, Halleck was in a bad mood. He worried that the Confederates were getting ready to attack Cairo or Paducah, his political games with his rival Buell weren't going anywhere, and he didn't much care for Grant's loose style.

Halleck was very unhappy at all the public praise being heaped on Grant, and not the superior intellect who was in charge. Grant had been getting so many boxes of cigars from admirers who had read of how he had fought with a cigar between his teeth that he gave up smoking the pipe, his traditional habit, and turned to cigars instead. Halleck decided to put Grant in his place. Halleck hadn't been getting reports from Grant, and on 3 March Halleck telegraphed General McClellan:

I HAVE HAD NO COMMUNICATION WITH GENERAL GRANT FOR MORE THAN A WEEK. HE LEFT HIS COMMAND WITHOUT MY AUTHORITY AND WENT TO NASHVILLE. HIS ARMY SEEMS TO BE AS MUCH DEMORALIZED BY THE VICTORY OF FORT DONELSON AS WAS THAT OF THE POTOMAC BY THE DEFEAT AT BULL RUN. IT IS HARD TO CENSURE A SUCCESSFUL GENERAL IMMEDIATELY AFTER A VICTORY BUT I THINK HE RICHLY DESERVES IT. I CAN GET NO RETURNS NO REPORTS NO INFORMATION OF ANY KIND FROM HIM. SATISFIED WITH HIS VICTORY HE SITS DOWN AND ENJOYS IT WITHOUT ANY REGARD TO THE FUTURE. I AM WORN OUT AND TIRED WITH THIS NEGLECT AND INEFFICIENCY.

McClellan promptly replied with a telegram that read, in part:

DO NOT HESITATE TO ARREST HIM AT ONCE IF THE GOOD OF THE SERVICE REQUIRES IT.

Halleck immediately sent out a message ordering Grant to stay at Fort Henry and place C.F. Smith in command. Halleck informed McClellan of the order in a telegram that stated Grant had "resumed his former bad habits", meaning he was out getting drunk.

Halleck's accusations had little basis in fact, and complaining from his comfortable headquarters in Saint Louis that a general in the field and on the move wasn't keeping up with proper paperwork was mindlessly petty. Although Grant complied with the order relieving him of command, he then pointedly replied that the communications lapse was due to the desertion of a telegraph operator who had taken dispatches with him. Grant added that he had gone to Nashville to confer with Buell because he had received no instructions from Halleck.

Halleck didn't care about facts, and the sniping between the two men intensified, until Grant asked to be completely relieved of duty. Then, abruptly, Grant was back in good graces with his boss. Halleck wired Grant:

INSTEAD OF RELIEVING YOU, I WISH YOU AS SOON AS YOUR NEW ARMY IS IN THE FIELD TO ASSUME COMMAND AND LEAD IT TO NEW VICTORIES.

Grant was restored to command on 15 March. There were a number of reasons for Halleck's change of heart. First, the Army adjutant general had stiffly informed Halleck that he had to put up or shut up: if Halleck had charges to make against Grant, he needed to make them formally, and provide evidence justifying them. Second, the Confederate withdrawal from Columbus relieved Halleck's worries about an imminent rebel offensive. Third, and most importantly, on 11 March Halleck had, as noted earlier, finally achieved his dream of putting Buell under his command. Halleck wired back the adjutant general that all the "irregularities have now been remedied."

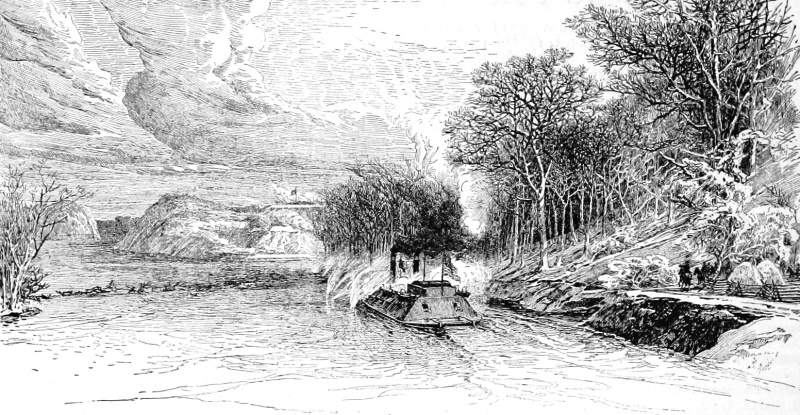

Halleck was happy, so Grant was happy. Grant went by steamship up the Tennessee from Fort Henry to rejoin his command. Halleck, exercising his new command prerogatives with undoubted satisfaction, ordered Buell to march his forces to reinforce Grant's.

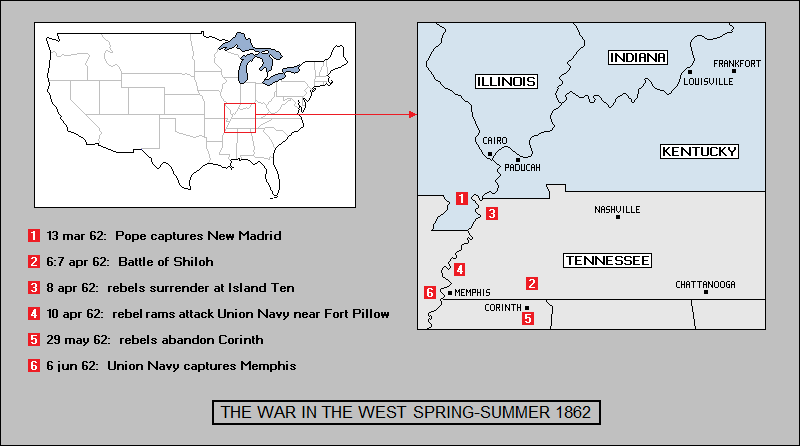

BACK_TO_TOP* While Grant was having his troubles with Halleck, the war on the Mississippi continued. The 7,000 men Polk had withdrawn from Columbus and sent to New Madrid found their new surroundings swampy and miserable at first, but soon realized that the swampiness made their position much easier to defend. Furthermore, just upstream from New Madrid, the Mississippi turned northward for a short distance, and then switched back south at the town in the river's meandering way. Federal vessels would have to slow down and maneuver around this double bend, and so it was an ideal position for a battery of guns.

The first bend in the river contained a flat, muddy island with the odd name of Island Ten, so called because it was the tenth island in the Mississippi below the confluence with the Ohio. It no longer exists; the Mississippi shifted its course after the war, and Island Ten became part of the riverbank. The Confederates mounted 39 guns at Island Ten, 16 of them on a floating battery, where they had a clear field of fire into any Federal vessels approaching from the north. At New Madrid itself, which overlooked the second bend, the rebels built three forts, with seven guns each.

Beauregard considered the defense of New Madrid absolutely vital. He had ordered the construction of a new defensive position named Fort Pillow a hundred miles (160 kilometers) downstream, but until that installation was completed, the batteries at Island Ten and New Madrid were the only things that stood between the Federals and the mouth of the Mississippi. The position was to be held "at all costs".

The Federals understood the importance of the position as well. Shortly after the fall of Fort Donelson, Halleck ordered Brigadier General John Pope to march south and take New Madrid and Island Ten.

Army operations on the Mississippi implied naval support, but Commodore Andrew Foote's ironclads had taken a pounding at Fort Donelson, and he had been wounded himself. After the battle, Foote had taken his ironclads back down the Cumberland to Cairo, to repair his vessels and tend to his wound. From Cairo, he considered what should be done next on the Mississippi.

The damage suffered by his gunboats had made Foote cautious, and the Mississippi was bigger than either the Tennessee or the Cumberland. It was much longer and wider, ran swifter, and the Federals would be moving downstream, not upstream -- meaning that if any of his ships were disabled, they would drift into the teeth of Confederate fire. Foote understood the difficulties, but he didn't want to sit and dither. On the morning of 4 March, he and his fleet left Cairo to attack the Confederate stronghold at Columbus. When they arrived, everything seemed peculiarly quiet.

A landing party went ashore and found the Stars & Stripes flying over the town. There were four companies of Illinois cavalry rummaging through the litter Polk's men had left behind and making themselves at home. The cavalrymen had come there on a scouting mission the day before, and found the place deserted.

General Pope had arrived at New Madrid the day before with four divisions, totaling 20,000 men, who he had marched down the west bank of the river after disembarking at Commerce, Missouri, north of Cairo. Pope, a vigorous, 40-year-old with an aggressive, brute-force mindset, immediately set siege to New Madrid and Point Pleasant, 11 miles (18 kilometers) downriver. He captured them both on 13 March 1862, seizing 25 cannon and large amounts of supplies, while the defenders ran across the river to take refuge in the fortifications at Island Ten.

Taking New Madrid had been easy, since it had not been defended with any enthusiasm, casualties on both sides having been light. The hard part was taking Island Ten. There was no practical way to move against it from the north on the east bank of the river, since it was almost surrounded by swamps. The only way in was from the south, along a road that ran through the town of Tiptonville. If there was only one way in, that meant only one way out as well. If Pope could get across the river and seize Tiptonville, the rebels would be trapped. To make the crossing, Pope needed transports -- and Foote's ironclads as well, since Confederate batteries overlooked the crossing and the rebels were patrolling the river with a little fleet of improvised gunboats. None of these warships were very impressive, but they were armed, and for the moment Pope had nothing on hand to deal with them.

Foote and his ironclads were delayed by further repairs at Columbus. They finally arrived on 17 March, only to be blocked by the guns of Island Ten. Foote was still hobbling around on crutches with his unhealed wound and lacked his usual nerve. He worried that running the guns would be suicide, and so decided to reduce Island Ten by siege instead. To this end, Foote had brought with him eleven mortar boats -- which were armored hexagonal barges 60 feet long by 25 feet wide (18.3 by 7.6 meters), each mounting a 13-inch (33-centimeter) mortar. As soon as he arrived, he set the mortar boats to firing on Island Ten from two miles (3.2 kilometers) upriver.

The shelling was impressively thunderous. There had been suspicions that the first time a mortar was fired, the mortar would simply drive itself through the bottom of the boat -- but each boat kept up a steady fire, with gun crews taking refuge on the outer deck, hands over ears and mouths open, to protect their ears from the concussion. However, the bombardment proved more noisy than effective. After days of firing, a Federal colonel was asked what the fleet of mortar boats was accomplishing. He replied wearily: "Oh, it is still bombarding the state of Tennessee at long range."

The Navy proving unproductive, Pope sought alternatives. He began to build floating batteries out of empty coal barges and boiler plate to force the crossing himself. He also set his men to building a canal. The peninsula that cut off Pope's soldiers from Foote's fleet was mostly flooded at the time. Pope's engineers suggested that waterways could be cut to link various watercourses and bypass the route past Island Ten, so 600 men were put to work. They devised ingenious means of cutting down trees below the waterline and pulling out stumps, and did a great deal of digging and dirty, hard work. In the end, they had a waterway 6 miles (9.7 kilometers) long, 50 feet (15.25 meters) wide, and a little over 4 feet (1.2 meters) deep.

Pope would have his transports, though Foote's gunboats drew too much water to make the passage themselves. In the meantime, the Navy continued their bombardment, and the Confederates remained firmly dug in on Island Ten.

BACK_TO_TOP