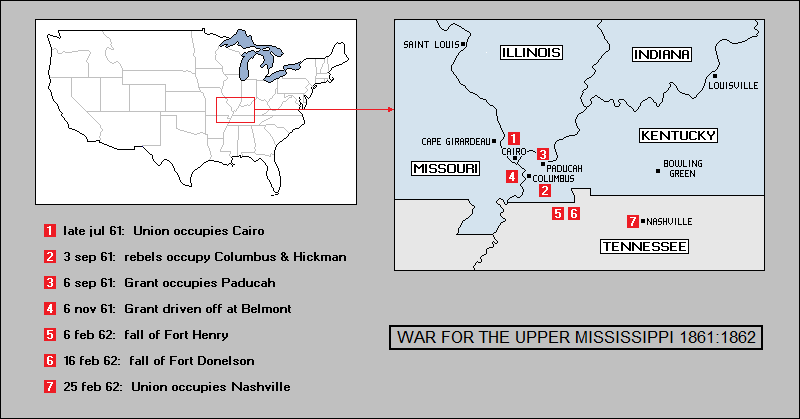

* In the early days of the conflict in the West the Union and the Confederacy, both poorly prepared for war, struggled for control of Missouri and Kentucky. By the summer of 1861, the Union had kept Missouri, with Major General John C. Fremont attempting to keep it under control and make further gains against the Confederates -- who were maintaining a loose defensive line into southern Kentucky to protect Tennessee and deny use of the Mississippi River to the Federals.

Fremont assigned command of Union forces intended to challenge the Confederates to Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant, while also arranging the construction of a set of river gunboats to support the drive. Grant moved energetically against the Confederates, throwing them off balance, though he did suffer a minor defeat at Belmont, Missouri, in November 1861. That was more than balanced by a Union victory at Logan's Crossroads in eastern Kentucky in January 1862.

* Following the bombardment of Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor in April 1861, fighting broke out between the Union and the break-away Confederate states. After the conflict started, the Confederacy relocated its capital from Montgomery, Alabama, to Richmond, Virginia. That meant a close proximity to the Union capital in Washington DC, with the Federal war in the East focusing on the capture of Richmond.

In the West, the secession of Arkansas and Tennessee put the front lines of the confrontation in Missouri and Kentucky. Missouri Governor Claiborne Jackson was pro-secessionist, but the citizens of Missouri were more mixed in their sympathies. Jackson plotted to take Missouri out of the Union by stealth, asking for weapons from the Confederate government, to help arm pro-secessionist Missouri militia.

Jackson failed to factor in US Army Captain Nathaniel Lyon -- a hot-headed Unionist who, with help from prominent citizens of Saint Louis, set up a Unionist militia, composed largely of immigrant Germans. In May 1861, Lyon's militia cleaned out the Saint Louis Armory, sending the weapons to Illinois to keep them out of secessionist hands, then marched on the camp of the secessionist militia, with Lyon telling them to surrender. They did so without a fight, but violent rioting then broke out in Saint Louis. Lyon's militia suppressed the rioters, with Jackson and other secessionists fleeing the city.

The Missouri state legislature, in Jefferson City, had been attempting to remain neutral, but Lyon's actions tilted the legislature into secession. Lyon -- now promoted to brigadier general and formally assigned to command all Union forces in Missouri -- marched his troops to Jefferson City, Governor Jackson, the secessionist legislature, and pro-secession Missouri state militia fleeing the city in mid-June. There was a noisy but largely bloodless fight between the two little armies at Boonville on 16 June, with the secessionist militia deciding to withdraw.

Lyon had preserved Missouri for the Union, through a coup that had evicted the properly-elected state government. As far as the government in Washington DC was concerned, the law was on Lyon's side, since Governor Jackson was guilty of treason in attempting to overthrow Federal government authority, and the state legislature had become his accomplice. However, the end result was that there would be a vicious little struggle between the two sides in Missouri all through the war.

The struggle for Kentucky was more nuanced. Governor Beriah Magoffin of Kentucky was secessionist, but the Kentucky legislature was not. Both the secessionist and Unionist factions in Kentucky were engaged in quietly building up their own militias. The secessionist militia was led by Brigadier General Simon Bolivar Buckner, while the Unionist militia was led by an energetic gorilla-sized bully of a man named William Nelson. Nelson was a Navy lieutenant who had decided to throw his weight for the Union in Kentucky, smuggling in arms and taking other measures. He was made an Army brigadier general as a reward; that was an unusual promotion path to say the least, but unusual times dictated unusual measures. Kentucky remained balanced in an uneasy neutrality. It couldn't last.

* Although Nathaniel Lyon had seized power from secessionists in Missouri, the Federal government still needed to tighten its grip on the upper Mississippi, to prevent the Confederacy from cutting what was left of the Union in half, as well as to retain staging areas where an offensive down the great river could be organized to perform that same division on the Confederacy. Accordingly, on 23 July 1861, Major General John Charles Fremont was sent to Saint Louis to take charge of the department.

Fremont was a well-known explorer of the Far West; he had been a senator and, in 1856, the first Republican candidate for president. After arriving in Saint Louis, Fremont focused his attention on the strategic waterways of the Midwest, which provided avenues into the Confederacy over which invasion forces could travel.

The Mississippi flowed southeast past Saint Louis, separating Missouri and Illinois. Farther south along the river was the town of Cape Girardeau, Missouri; then Commerce, Missouri; and then, at the southernmost tip of Illinois, where the Ohio joined the Mississippi, the strategic town of Cairo (pronounced "KAY-row", not "KAI-row"). To the east, the Ohio snaked along the northern border of Kentucky and the southern borders of Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. Not too far upriver from Cairo, the Tennessee River flowed into the Ohio at the town of Paducah, Kentucky. A little farther upstream, the Cumberland added its waters to the Ohio as well.

The Tennessee and the Cumberland were natural pathways into rebel territory. The Tennessee cut through western Kentucky and Tennessee, then ran across northern Alabama. The Cumberland twisted through western Kentucky, across the northern regions of Tennessee, and then back into central Kentucky. They were both navigable by steamships along much of their length.

Fremont lacked resources to move quickly, and he was also spooked by reports of Confederate forces gathering to move against him. Fremont, however, believed he was facing Confederate forces twice as they really were, and the Confederates had their own problems at the time. Fremont got even more spooked when Lyon and his troops got into a fight with a larger Confederate force at Wilson's Creek, in southwest Missouri, on 10 August. There was a vicious brawl, with Lyon killed, and his troops falling back off the battlefield.

Luckily for Fremont, the battle chewed up the Confederates as badly as the Federals, and the Confederates were not able to follow up their win. Fremont didn't know that, and screamed for reinforcements -- which were forthcoming. However, Fremont's leadership in the crisis left something to be desired; he was not a very good administrator, and had an imperious mindset. A European military observer commented that Fremont was "inclined to dictatorship"; a Union soldier described him a little more colorfully as a "spread-eagle, show-off, horn-tooting general." Union President Abraham Lincoln Administration would find him insubordinate and a trial. At the end of August, Fremont greatly over-reached himself by abolishing slavery in his department. He was over-ruled by Lincoln, who began to consider replacing Fremont in command.

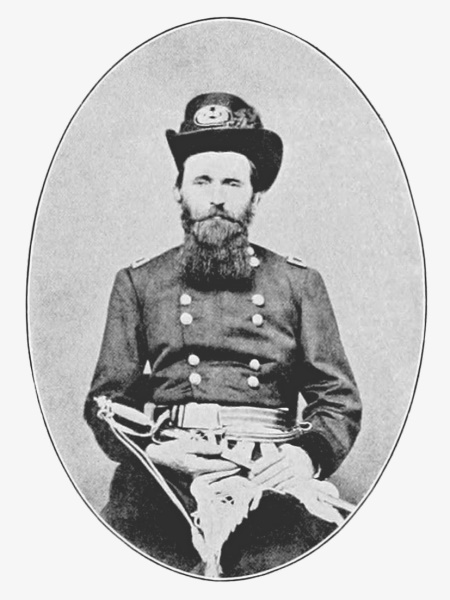

BACK_TO_TOP* Despite these problems, Fremont had been getting some things done. He had bought river steamers and had them rebuilt into gunboats, and ordered the construction of 38 mortar boats. He had also made an appointment that would have consequences he could not have imagined: on 28 August, he put Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant in command at Cairo.

U.S. Grant had actually been born Hiram Ulysses Grant, but when he arrived at West Point in 1839, they entered his name incorrectly as Ulysses Sampson Grant. He liked the new name the army had given him, and left it as entered. In 1861, there was nothing in Grant's appearance or past history that would have much impressed an onlooker. He was 39 years old, quiet, nondescript, even shabby in appearance. He had been regular army and had served with distinction in the Mexican War, finding something in combat that appealed to him. However, he had left the army seven years previously under a cloud of drunkenness, and had spent the intervening time sliding down to poverty, finally reduced to working as a clerk in his father's general store.

When the war came, he helped organize a company of soldiers in his hometown of Galena, Illinois. He was offered the captaincy of the company, but turned it down, believing that as a West Pointer he should settle for no less than a colonel's rank -- which, given the scarcity of trained officers, was perfectly reasonable. He went with the company to Springfield, Illinois, to seek his fortune and was pressed into service by Governor Richard Yates as a mustering officer, in which capacity he attracted favorable attention.

Grant then sought a combat command; he didn't have much luck at first, but then Governor Yates offered him command of the 21st Illinois, a volunteer regiment that was in a state of chaos and near-mutiny under its current colonel. Grant quickly put the regiment in order and led it in marches against Confederate guerrilla bands in Missouri. Grant's competence further impressed Governor Yates, as well as Illinois Congressman Elihu B. Washburne. When the state was allowed to name four brigadier generals, Grant was among the chosen. Fremont was also impressed with Grant, seeing in this quiet fellow an "unassuming character" given to "dogged persistence" and "iron will".

* General Fremont was opposed by Confederate Major General Leonidas K. Polk. Polk had been a West Pointer; he became an Episcopal bishop in Louisiana. When the war came, Confederate President Jefferson Davis -- who had been a classmate of Polk's at West Point -- made him a general, and put him in charge of the defense of the central Mississippi region. General Polk wasn't exactly thrilled with the assignment. Although General Fremont was worried about what the Confederates might do to him, the Confederates had much more reason to worry about what Fremont might do to them.

The focal point of the struggle was Cairo, where Ulysses Grant was building up his forces. The little town was dirty, humid, and prone to flooding that reduced its streets to rivers of mud. One of the advantages of such conditions was that the troops training there found the place so miserable that they were looking forward to going into action. Downstream from Cairo along the Mississippi were obvious vulnerable points where the Federals could make trouble for the Confederacy, such as the Kentucky towns of Columbus and, further south, Hickman. The Federals were clearly preparing to move on Columbus, and were making Polk nervous. Upstream from Cairo along the Ohio was Paducah, Kentucky, the gateway to the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers; a Federal seizure of Paducah would also be a setback for the Confederacy.

On 3 September 1861, Polk's forces moved north from Tennessee to occupy Columbus and Hickman. Kentuckian neutrality, such as it was, was finally over -- and significantly, it had been violated by the Confederates, though Grant had been preparing to move himself before Polk beat him to the punch. There was an immediate furor in the Confederacy over this action and the Confederate Secretary of War, L.P. Walker, ordered Polk to withdraw at once, but Jefferson Davis overruled the order.

Grant reacted swiftly, throwing everything he could on steamboats, and moving upstream to occupy Paducah on 6 September. He notified Fremont, but did not wait for approval. The Unionist Kentucky legislature backed up Grant's move by requesting Union assistance to expel the Confederate invaders. Governor Magoffin resigned, and went South to work for the Confederacy.

Brigadier General Robert Anderson, who had been in command of Fort Sumter when the Confederates bombarded it, had been sent to Ohio in the spring to raise troops, and was in charge of the Federal military forces intended to occupy Kentucky. He was in no condition for the job. He was too old, and the combined stresses of the siege of Fort Sumter and divided feelings for North and South weakened him. Furthermore, he had few soldiers, since most of the regiments that he had raised had either been sent to Saint Louis or to Washington. Fortunately, he had two West Point-trained subordinates to help: Brigadier Generals William T. Sherman and George H. Thomas.

William Tecumseh Sherman was a West Pointer who had been in charge of a military academy in Louisiana when the South left the Union. He had gone to Saint Louis to run a streetcar company, getting caught up in the riots in May. He then offered his services to the Federal government; he was offered a brigadier's commission by President Lincoln. Sherman turned it down and asked for a colonel's rank instead, saying he wanted to work his way up. Lincoln, who was continually plagued by people badgering him for as much as they could get out of him, was astonished, but gave Sherman command of a new regiment of regulars. Sherman saw action at the Battle of Bull Run in Virginia on 21 July 1861, leading to his promotion to brigadier general a month after the battle, and then was sent West.

Thomas was a Southerner, a Virginian, who had remained loyal to the Union. Earlier in the year, Lincoln had hesitated to give Thomas a general's commission since other Virginian officers had joined the Confederacy -- but had agreed to do so when Sherman reassured the President that Thomas was loyal to the Union. Coming away from the interview with the President, Sherman ran into his friend Thomas on the street and congratulated him: "Tom, you're a brigadier general!" Thomas was notoriously unflappable and hardly blinked; Sherman grew worried and asked: "Where are you going?"

Thomas replied: "I'm going South." Sherman, who was notoriously exciteable, cried out: "My God, Tom! You've put me in an awful position! I've just made myself responsible for your loyalty!"

Thomas amiably replied: "Give yourself no trouble, Billy. I'm going South at the head of my troops." Thomas could not pass up having some fun at his friend's expense. Thomas would not "go South" just yet, however. Anderson sent Sherman to Saint Louis to plead for reinforcements and sent Thomas to take charge of the Kentucky Home Guard, while Anderson himself set up headquarters in Louisville and stepped up recruiting efforts.

In the meantime, the Federal apparatus in Kentucky was doing whatever it could to ensure its own survival, arresting individuals judged insufficiently loyal and holding them, as had become the fashion of the times, without pretense of due process. The quiet life that Kentucky had enjoyed over the summer was over, and the battlefront of the war now extended all along the border between Tennessee and Kentucky.

* Far upriver on the Mississippi, Confederate General Polk had blundered in occupying Hickman and Columbus, Kentucky. Not only had Kentucky been lost to the Confederacy, but Grant's prompt occupation of Paducah left Polk's advance force hanging out on a limb: the rebels had seized the front door, only to find the Federals in control of the back. The Union threat to Tennessee and points south had become more tangible, and so Jefferson Davis appointed General Albert Sidney Johnston to organize the defense of the region.

The Confederates had all of 50,000 men to defend Missouri, Arkansas, and Tennessee against Federal forces almost twice as big. The fact was that no more resources were available, but General Johnston seemed to be the kind of leader who was up to the challenge -- a career army officer, 58 years old, and highly regarded by almost all. There was something in his upright, intelligent, and decent nature that commanded respect, even though his capacity for actual combat command was as untested as almost every other senior officer's in both armies. He had been two years ahead of Jefferson Davis at West Point, and Davis had a serious case of hero worship of the man. Even William T. Sherman called Johnston "a real general".

Johnston had been the US Army officer in charge of the West Coast when war broke out, but had made no secret of his intention of going South. When his replacement had arrived in California, Johnston resigned, traveled by horseback to Texas, and from there went on to Richmond. Jefferson Davis had made him a general on the spot and sent him to Nashville, where he took command on 14 September 1861.

BACK_TO_TOP* Albert Sidney Johnston had plenty to keep him busy. One of the first problems was the matter of Eastern Tennessee. The hill folk in Confederate states had little sympathy for slavery and secession; Lincoln wished to help Unionists in east Tennessee, who were sullenly enduring a Confederate military occupation. Not only would liberating the area be considerate of the patriots there, but a Union seizure of the mountain regions would greatly disrupt the Confederacy. It would break the rail connection between Virginia and Tennessee through the pass known as the Cumberland Gap, and provide a jumping-off point for Federal incursions into other regions of the South.

In late September 1861, President Lincoln wrote that he wanted an expedition organized to evict the Confederacy from east Tennessee. The operation would take place in two steps: a Federal army under the command of George Thomas would move in to the Cumberland Gap and occupy Knoxville, the central city of the mountain region. In the meantime, local Unionists, trained and financed with Federal assistance, would rise up against the Confederate authorities.

That was the plan -- but the Confederates didn't cooperate. In early September, when Polk occupied Columbus and Hickman, the Confederate military commander in East Tennessee, General Felix Zollicoffer, had moved forces into southwestern Kentucky, blocking Federal movements towards the Cumberland Gap. Although Zollicoffer's forces were relatively weak, the Union Army didn't have the leadership in the area with the will to deal with them. Robert Anderson had been suffering poor health since the war began, and after the Federal occupation of Kentucky, his failing health had become obvious to all, himself included, that he was no longer fit for command.

On 6 October, Anderson was relieved of duty by a respectfully-worded telegram from Major General Winfield Scott, the commander of the US Army, and went into effective retirement, to be replaced by his subordinate, General Sherman. Anderson would spend the rest of the war in New York City, admired on the streets as the hero of Fort Sumter, while he followed newspaper reports on the war. He took a particular interest in the exploits of Sherman, who had served under him as a lieutenant, years before the war. "One of my boys," Anderson called him.

In the face of this Union management shuffle, Johnston was demonstrating considerable energy in preparing for the Federals along his front. Zollicoffer held the Cumberland Gap in the east; Polk was holding the Mississippi firmly in the west; and Forts Henry and Donelson were being built in Tennessee, just south of the Kentucky border, to block Union movements down the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers respectively. To pin the center of his line, Johnston placed Kentucky General Simon Bolivar Buckner with about 10,000 men at Bowling Green, in south-central Kentucky, to hold the Louisville-Nashville Railroad. Buckner was aggressively sending out raiding parties to disrupt the Federals, led by enterprising commanders such as Colonel Patrick Cleburne, a tough and professional Irishman who had served in the British Army and become a lawyer in Arkansas. Kentucky loyalists were frantic, and Sherman was convinced that the rebels would soon move on Louisville.

Sherman started his new job in a state of complete confusion; he was in no mental condition to direct an offensive against the Confederates. The offensive went ahead anyway. In late October, a few regiments of Union-trained Tennessee loyalists and a larger force under Thomas began their move from northwest and central Kentucky toward east Tennessee. Thomas moved to the outskirts of the mountain region, and east Tennessee Unionists rose up enthusiastically, burning five railroad bridges, fighting with rebel patrols, and in general terrifying Confederate authorities.

The Unionists were betrayed. Sherman did not think the project was worth his time and so, fearing an imminent rebel attack all across Kentucky, recalled Thomas, leaving the uprising in the mountains twisting in the wind, to be quickly crushed. Five captured ringleaders were hanged immediately. Confederate Secretary of War Judah Benjamin, in transmitting the instructions to Knoxville, added: "It would be well to leave their bodies hanging in the vicinity of the burned bridges."

Their followers were sent to prison. A secessionist observer commented that "bad men among our friends" were hunting down the insurrectionists "with all the ferocity of bloodhounds". Sherman did not escape the fiasco unscathed. He had gone completely unstrung, believing he needed 200,000 men to hold Kentucky. He was relieved of command on 15 November and sent to the rear in Missouri. A few weeks later, he was given indefinite leave. Sherman's wife came to take him home to Ohio to recollect his wits. The word went around that he had gone mad. He was replaced, as part of a reorganization of the Western theatre of war, by Brigadier General Don Carlos Buell.

The good news was that Buell was not anywhere near as buffaloed by the activities of Albert Sidney Johnston as Sherman had been. The bad news was that Buell was still in no hurry to exploit Confederate weaknesses. Buell wanted to get his soldiers organized and trained before he took action. What happened to the Unionists in east Tennessee was of very little interest to him, then or later, no matter how hard Washington pressed him on the matter. The Federals had lost an opportunity. There had been little to prevent them from seizing east Tennessee except the timidity of their own military commanders. Had they done so, they would have caused the Confederacy serious harm at little cost.

Some of the caution on the part of Sherman and Buell had a basis in fact: fighting battles with poorly trained and ill-equipped troops could lead to disaster. However, Nathaniel Lyon had demonstrated that ragtag forces could do substantial things, if they had the right leadership, and as U.S. Grant observed later, a general who took the time to ensure his preparations were complete gave his adversaries the same amount of time to refine their preparations as well -- with no necessary advantage to either side when the time came to fight.

* Despite the continuous low-level violence in Missouri, General Fremont's campaign against the rebels resulted in only one battle, which took place nowhere near him and his army -- and then only after he had departed from the scene.

The guerrilla fighting in Fremont's rear had worried him. One particularly troublesome irregular warrior working operating in the southeast corner of the state was an eccentric but energetic guerrilla leader named M. Jeff Thompson. Thompson had once written the Confederate authorities that all they had to do to get rid of the Saint Louis Unionists was destroy the local breweries and seize all the beer: "By this means the Dutch [Germans] will all die in a week and the Yankees will then run from this State."

Fremont found Thompson irritating. He had also heard that Confederate General Polk was sending troops west across the river to assist Sterling Price, and so Fremont ordered General Grant to make a show of force to distract Polk, who was operating out of the rebel stronghold at Columbus, Kentucky, and put Thompson on the defensive. On 3 November 1861, Grant sent a column of troops south along the Missouri side of the Mississippi to try to trap Thompson.

On receiving a report on 5 November that Polk actually was sending troops to help Price, Grant decided to throw in more troops. On 6 November, he put 3,100 men onto four steamboats and steamed down the Mississippi with an escort of two wooden gunboats. In the dark hours of the next morning, 7 November, Grant received a report that Polk was ferrying forces across the river to destroy the column Grant had sent south on the 3rd. Grant decided to hit first, attacking Belmont, Missouri, on the west bank of the river, across from Columbus.

In reality, Thompson was lying low for the moment; Polk was not sending Price any real help; and the Federal column was under no serious threat -- but Grant landed north of Belmont early on 7 November anyway, looking for a fight. In response, Polk sent four regiments under the command of Brigadier General Gideon Pillow across the river to reinforce the small garrison already in Belmont, and Grant's advance quickly led to a confrontation.

The Federals overwhelmed the rebels after about two hours of fighting. The Confederates fell back in disarray: "We are whipped! Go back!" -- they cried to new reinforcements moving across the river. Unfortunately, as had happened with green troops in earlier battles, winning disorganized the Federals as much as losing confused their adversaries, and it quickly became apparent that the Federals hadn't really won much. Belmont was so obviously exposed that Polk hadn't really believed the Yankees would seriously try to take it, and the Federals ended up under heavy fire from Confederate artillery sited on bluffs across the river, while Confederate reinforcements threatened to turn the tables on the Union men.

An aide cried out: "General, we are surrounded!"

Grant replied, as usual matter-of-fact: "Well, we must cut our way out as we cut our way in."

There were 5,000 angry Confederates on the field and that was no simple task, but Grant directed his men energetically and got them out, though equipment had to be abandoned. He was the last man out at the landing, except for one regiment that had marched upstream to be picked up later. The last transport had pushed off the bank, but the captain, recognizing Grant on horseback, had a plank slid out to him.

Grant had already had one mount shot out from underneath him; he was in considerable danger, for General Polk had seen him and told his staff: "There is a Yankee; you may try your marksmanship on him if you wish." Fortunately for Grant, nobody felt that was particularly sporting. Grant had an almost supernatural knack for horses, and his new horse seemed to understand the situation. It stepped over the edge of the bank, tucked its hind legs underneath its rump, and "without hesitation or urging", slid down the bank and trotted up the plank.

Both sides took about 600 casualties at Belmont, but it was clearly a Union defeat. The Northerners were discouraged, while the Confederates crowed over their victory. Neither point of view was quite the truth. Although the fight at Belmont was a serious battle, it amounted to nothing strategically, and the Union side of the score card showed that the Federals had generals who were eager to fight. Grant's men obtained some valuable combat experience, they saw the rebels break and run on the field, and when things went wrong, their commander kept a cool head and got them out in good order under fire -- one of the most difficult of military maneuvers. There was some spirit of aggressiveness in the Federals, and if it ever got rolling, it might be hard to stop.

* Getting it rolling was a problem, the difficulty being the organization of Union forces in the region. Fremont, having antagonized the Lincoln Administration by abolishing slavery in his department, was replaced in command in early November by Major General David Hunter. A reorganization in mid-month then broke Fremont's old Department of the West into three parts:

David Hunter was put in charge of the Kansas Department; Major General Henry Halleck became commander of the Department of Missouri, making him Grant's immediate superior; and, as mentioned earlier, Don Carlos Buell was assigned to the command of the Department of Ohio, replacing William Tecumseh Sherman, who was put under Halleck's command until Halleck decided to send him home.

The command arrangement placed Halleck and Buell in equal positions of authority. Since neither man was particularly diplomatic or far-sighted, the split command arrangement immediately led to rivalry and antagonism, crippling coordination between their forces. Grand plans were discussed and promoted, but for the moment the two armies did nothing.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Confederate defense of the region appeared formidable on the surface, with Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston holding a line across southern Kentucky:

The Confederate defense wasn't as strong as it appeared. The rebels had some great fighters in their ranks, such as the tough Irishman Pat Cleburne; a daring Kentucky captain of cavalry named John Hunt Morgan; and, most significantly, another cavalryman, Lieutenant Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest of Tennessee. Unfortunately, the rebels were still outnumbered almost two to one by the Federals -- and if the Union decided to give Albert Sidney Johnston's defenses a good hard kick, they would collapse in a heap.

If they broke, Nashville would almost certainly fall. The Confederacy could not afford to lose that city, since it contained foundries forging cannons; mills turning out hundreds of pounds of gunpowder each day; clothing factories producing uniforms; warehouses full of supplies; and it was a crucial transportation hub.

The critical point in Johnston's line was where the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers flowed south through the Confederate line in west Tennessee, and then ran deep into Confederate territory. These rivers were navigable by steamboat over much of their length, with the Cumberland being effectively an open highway to Nashville. The defense of these vital waterways rested on Fort Henry on the Tennessee and Fort Donelson on the Cumberland. The forts were not ideally sited, since Albert Sidney Johnston's advance to Bowling Green in central Kentucky left the forts well behind the furthest extent of Confederate lines -- but there was a rail line from Bowling Green to Memphis that ran behind them, allowing the forts to be quickly reinforced if need be. However, the rail line was vulnerable; if the Federals got their gunboats past the forts, they could immediately destroy the railroad bridges across the rivers and cut the line.

Albert Sidney Johnston's aggressive game of bluff had worked so far, intimidating Halleck and Buell, even driving William Tecumseh Sherman off his head for the moment. Unfortunately for Johnston, the Yankees weren't the only ones who believed his propaganda. The Southern press trumpeted the strength of his armies, but if their true weakness became apparent, it would be a staggering disillusionment to the citizens of the Confederacy.

* Albert Sidney Johnston's focus was of course in the critical center, but the first shock to his defenses came at the eastern end of his line. After occupying the Cumberland Gap in the fall, in mid-December General Zollicoffer had been ordered to move northwest out of the mountains to the town of Mill Spring, 70 miles (113 kilometers) away on the southern bank of the Cumberland River. Zollicoffer had no military experience, and so Johnston decided to send a professional, George B. Crittenden, to take charge of the region. Crittenden was a West Pointer, a veteran of the Mexican War and Indian fighting, and a Kentuckian. He was one of the two sons of Senator John J. Crittenden; George Crittenden became a Confederate major general, while his younger brother, Thomas L. Crittenden, was a brigadier general in the Union Army.

When George Crittenden arrived in Knoxville to take command, he found that the enthusiastic Zollicoffer had abandoned the relative safety of Mill Spring and gone north across the river. Zollicoffer was now exposed to attack by superior Union forces to the north, with a wide deep river in his rear, while he attempted with little success to enlist the locals in the Confederate Army and had his men on starvation rations. Crittenden sent a messenger to Zollicoffer with an order telling him to move back across the river immediately, but when Crittenden went forward to inspect Zollicoffer's forces in early January, he found that Zollicoffer had ignored the order, since he liked his current campsite, at a place called Beech Grove. Besides, Zollicoffer explained, there were reports that the Yankees were advancing, and withdrawing would seem cowardly.

Crittenden was shocked, and quickly found out it was all true. Federal forces under George H. Thomas were moving forward to attack the rebels. At the beginning of the month, Thomas had moved out of his camp at Lebanon, Kentucky, about 100 miles (160 kilometers) northwest of Mill Spring, with 5,000 men. The march was a nightmare, with cold January rains turning roads into quagmires, and striking down Union soldiers from sickness and exposure. The march cost the little army about 20% of its men.

Crittenden took command from Zollicoffer, but decided against recrossing the river, fearing that Thomas would catch his force in the middle of the move and destroy it. Crittenden prepared to be attacked, but the rains grew worse and the Federal advance turned into a further week of cold, misery, and mud. Thomas was nothing if not persistent, however. He was known as "Old Slow Trot", partly because of a back injury that prevented him from riding a horse at a gallop, but also because he was almost completely unflappable, given to plodding methodicalness. By 17 January, his troops had reached a place named Logan's Crossroads, 9 miles (15 kilometers) away from the rebels, where he went into camp to dry out before going into battle.

Crittenden had no intention of letting Thomas strike when he pleased. The Federal campsite at Logan's Crossroads was split by a stream named Fishing Creek, and Crittenden figured that with Fishing Creek too swollen to be crossed, he might be able to take the Yankees by surprise in a dawn attack and destroy them in parts. It was a long shot, but it was better than simply waiting to be wiped out. In the darkness of the night of 18 January 1862, the rebels moved out.

To no surprise, the rain and mud that had been making the Federal advance so dreary now worked against the Confederates. A night march would have been difficult enough under the best of circumstances; under such wretched conditions, it required superhuman stamina. The rebels pushed on, and early in the morning of 19 January 1862, they ran into Federal cavalry patrols. Shots were exchanged; the advantage of surprise was lost, but Crittenden knew that fighting it out with the Yankees then and there was far preferable to trying to backtrack through the mud with the aroused enemy right behind him, and went forward with the attack.

Zollicoffer led the rebels into battle and made headway at first. The two forces were actually well-matched numerically, with about 4,000 fighters on each side -- but the Confederates were exhausted from the night march, and one regiment that was armed with old flintlock rifles, which wouldn't fire in the rain, had to be pulled out of the fight. Worse, Crittenden's belief that Fishing Creek would be too swollen for the Federals to cross turned out to be deadly wrong, with the number of Union soldiers in front of the Confederates growing to an intimidating mass.

Then Zollicoffer made one last blunder. Wearing a white rubber raincoat that made him very visible, he rode out between the lines during the fighting and became confused. He shouted an order to a colonel, who turned out to be a Yankee; the Federal colonel shot Zollicoffer in the chest with a revolver, killing him. Zollicoffer's Tennessee troops loved their commander, and his death was the final stroke; they broke and ran, and suddenly the rebels were in full retreat. Thomas attempted to pursue, but the unburdened Confederates were able to move faster down the muddy roads.

The Confederates crossed the Cumberland in relays during the night using a decrepit old stern-wheeler. When done, they burned the steamship, leaving behind 500 men killed, wounded, and taken prisoner; 12 guns; 1,000 horses and mules; 150 wagons; and half a dozen regimental colors. The Federals only lost about 250 men. Crittenden's force had been effectively wiped out. Although he had done what he could in a difficult situation, he was accused of everything from treason to drunkenness, to be eventually broken in rank and reduced to obscurity.

As bad as the defeat was for the Confederacy, it fell short of complete disaster. Thomas wanted to continue to march to Knoxville and liberate eastern Tennessee, but the rains kept on falling and his men were on half-rations. Thomas was forced to withdraw. Despite that, the North still had a clear-cut battlefield victory to celebrate.

BACK_TO_TOP* Not everyone celebrated, however. In Saint Louis, General Henry Halleck found the prospect of being shown up by his rival General Buell unnerving. Halleck was effectively focused on paperwork, nothing that really resembled a warfighter; but it was beginning to seem necessary to take action if he wanted to hang on to his command.

It had taken Halleck time to open his eyes. General Grant had been threatening General Polk in his stronghold at Columbus, Kentucky, through most of the middle of January 1862, probing rebel defenses and trying to intimidate the Confederates. Grant had found the exercise useful and interesting, and went to Halleck to propose a general offensive. Halleck was disinterested and curt -- both were typical of him -- with Grant leaving the meeting discouraged.

It wasn't like Grant to stay discouraged for long. On his return to Cairo, he found a message from one of his brigadiers, a tough old regular named C.F. Smith who had been commandant of West Point when Grant was a cadet there. Grant held Smith in high regard; at first, he had difficulty giving the older man orders, though Smith quickly put him at ease. Smith been probing up the Tennessee on a gunboat to near Fort Henry while Grant had been demonstrating above Columbus. Smith reported: "I think two ironclad gunboats would make short work of Fort Henry." Grant, the wind back in his sails, telegraphed Halleck:

CAIRO, JANUARY 28 MAJ. GEN H. W. HALLECK SAINT LOUIS, MO.: WITH PERMISSION, I WILL TAKE FORT HENRY ON THE TENNESSEE, AND ESTABLISH AND HOLD A LARGE CAMP THERE. U.S. GRANT BRIGADIER GENERAL

Halleck, under pressure to do something, was reconsidering the rough treatment he had given Grant three days earlier. Halleck had also just received intelligence that Confederate General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard was leaving Virginia for Kentucky with 15 regiments. That was the last straw for Halleck. On the 30th, he wired Grant:

MAKE YOUR PREPARATIONS TO TAKE AND HOLD FORT HENRY. I WILL SEND YOU WRITTEN INSTRUCTIONS BY MAIL.

There was a slight problem with this order: Fort Henry was in Tennessee and fell under Buell's jurisdiction, but Halleck simply requested permission from Major General George B. McClellan -- at the time, Halleck's effective superior officer, in Washington DC -- and then informed Buell. Buell was furious, but there was nothing he could do about it; Halleck had moved first.

Halleck's instructions to Grant were short and direct, providing the latest intelligence and then directing: "You will move with the least delay possible." Grant promptly replied: "Will be off up the Tennessee at 6 o'clock. Command, twenty-three regiments in all." The fleet departed on the morning of 2 February 1862.

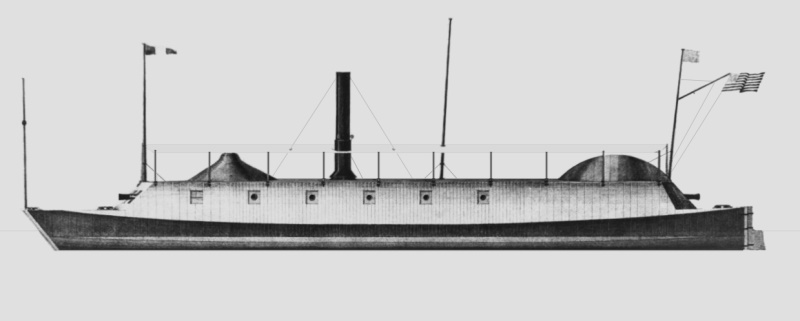

* The "ironclad gunboats" Grant's man Smith had believed would crush Fort Henry were something new and strange, the product of Yankee ingenuity and improvisation. A year earlier, a Navy officer, Commodore John Rogers, had been charged with getting warships on the Mississippi and its tributaries as fast as possible -- oddly, the effort was driven by the War Department, not the Navy Department, the Army having a more immediate interest in river warfare than the Navy. Rogers had purchased three flat-bottomed side wheelers in Cincinnati, had their upper works stripped off, and added reinforcing timbers, five-inch (13-centimeter) oak sheathing, and four to eight guns each. The three wooden gunboats, named the LEXINGTON, the CONESTOGA, and the TYLER, were operational by the end of summer. These vessels were more powerful than anything the Confederates had on the river and would prove very useful. However, while their oak armor would be proof against small-arms fire, large cannon would make short work of them. Something more formidable was needed.

While the three "timberclads" were being completed in August 1861, Fremont had contracted for the construction of ironclad gunboats with an industrialist named James B. Eads, who would later become one of America's best-known bridge builders. The vessels were based on a general design drawn up by a Cincinnati engineer named Samuel M. Pook. They were river steamboats whose layer-cake multiple decks had been replaced by a single deck with sloping armored sides, broken by portholes for cannon. An armored pilot house and twin smokestacks protruded above the gun deck.

The first two ironclads, the ESSEX and the BENTON, were converted riverboats. The ESSEX, converted from a ferry, was a relatively small vessel, mounting only five guns, but the BENTON -- a converted catamaran "snag boat" that had been designed to pull trees out of river bottoms and salvage sunken vessels -- was over 200 feet long and 72 feet in beam (60 by 22 meters), was covered with three and half inches (9 centimeters) of iron armor plate, had a crew of 176, and mounted 16 guns.

Seven other ironclads, including the SAINT LOUIS, CARONDELET, LOUISVILLE, PITTSBURGH, MOUND CITY, CINCINNATI, and CAIRO, were built from scratch. Each of these was 175 feet long and over 50 feet in beam (53 by 15 meters), with sloping sides mounting two and a half inches (6.4 centimeters) of armor plate, and carried 13 guns. Eads' work crews, working at Carondelet near Saint Louis and Mound City, ran in high gear to build the vessels, and the first was completed in October 1861.

Eads had completed all these monsters, often called "Pook Turtles" after Samuel Pook, by January 1862. They left much to be desired. They were underpowered; under-armored; an oven for sailors in hot weather; and their low draft meant that their boilers had to be right in the middle of the gun deck, which would turn one of the ironclads into a steaming cauldron if a cannonball punctured them. Despite these limitations, they were highly effective and intimidating weapons.

Although the gunboats had been built by the Army and the crews were soldiers, recruited from river-boatmen and the like, the Navy had offered to provide skippers, and the Army accepted -- though the captains were placed under the Army operational chain of command, an arrangement that would prove somewhat awkward. The Navy sent out some of its best officers, most prominent among them being Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote. Foote was a Connecticut Yankee, 56 years old, a decent, straightforward man, if said to be "savage and demoniacal" when angry. He had spent forty years in the Navy, doing the Lord's work, fighting slavers and demon whiskey. Twenty years previously, he had captained the first temperance ship in the Navy, and each Sunday he held a Bible school for his sailors. Despite Grant's occasional indulgence in the bottle, the two men got along splendidly, for they had some things in common: steely resolve and a burning desire to crush the rebels.

On the evening of 3 February 1862, the fleet left Paducah, Kentucky, and steamed up the Tennessee towards Fort Henry in the gloom and rain. There were four ironclad and three wooden gunboats, escorting nine transports carrying a division of troops. Once that division had landed, the transports were to go back downstream and return with a second division, ferrying a total of 15,000 men into battle.

BACK_TO_TOP