* John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry had made secession inevitable. With the election of Abraham Lincoln, the breakup of the Union began. Pressure rose towards a clash, which began with the new Confederate state firing on Fort Sumter.

* As the presidential election of 1860 approached, the drive to secession completed the split in the Democratic Party. The Democratic convention took place in Charleston, South Carolina, in late April, and ended with the Southern Democrats walking out. The Northern wing of the party nominated Stephen Douglas as their presidential candidate, while the Southern wing nominated Senator John C. Breckinridge of Tennessee. In reality, the Southern wing wasn't after the White House; the true goal was secession from the Union.

One of the men of influence at the convention had been Alexander Stephens, an ex-congressman from Georgia. Stephens was the most dedicated of State's Rights men, but one who dreaded the idea of secession all the same. A friend asked him a short time later: "What do you think of matters now?" Stephens replied: "Think of them?! Why, that men will be cutting one another's throats in a little while. In less than 12 months we shall be in a war, and that the bloodiest in history."

Many of those pressing for secession thought all the talk of war in the air was just that, talk, some saying that a "single handkerchief" would be all that was needed to clean up the blood spilled by secession. When push came to shove, the greedy and spineless Northerners wouldn't fight. People like Stephens knew better: there would be war. What else could happen? When two sides have a disagreement and one side cuts off further discussion, the only choice left to the other side is to either give up, or resort to force.

The Constitutional Union Party, what was left of the old Whig Party, nominated John Bell of Tennessee. In the splintered political landscape, the Republicans had every reason to believe they could put one of their own into the White House. The Republican convention was held in May in Chicago, Illinois, drawing an enthusiastic crowd of 25,000.

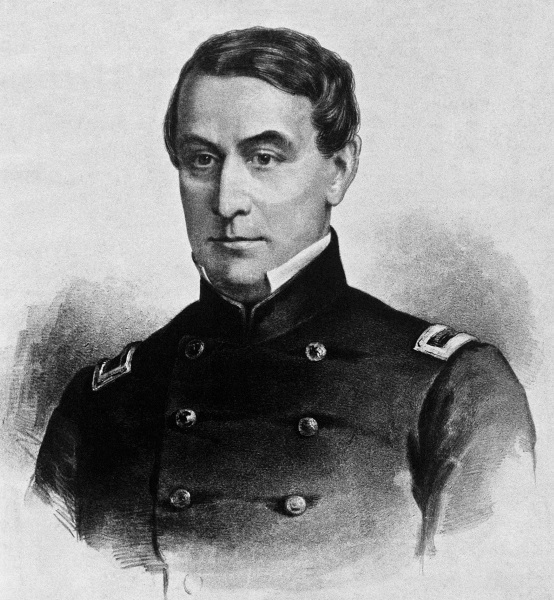

The front-runner for the nomination was Senator William H. Seward of New York. Other hopefuls were Governor Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, Judge Edward Bates of Saint Louis, Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania, and Abraham Lincoln. With his shrewd campaign manager, Thurlow Weed, Seward seemed unbeatable, since he was the most prominent Republican and had powerful backers. However, he also had many enemies, and Lincoln was a canny political operator himself. The final vote was called on 18 May, and Lincoln became the Republican candidate for president.

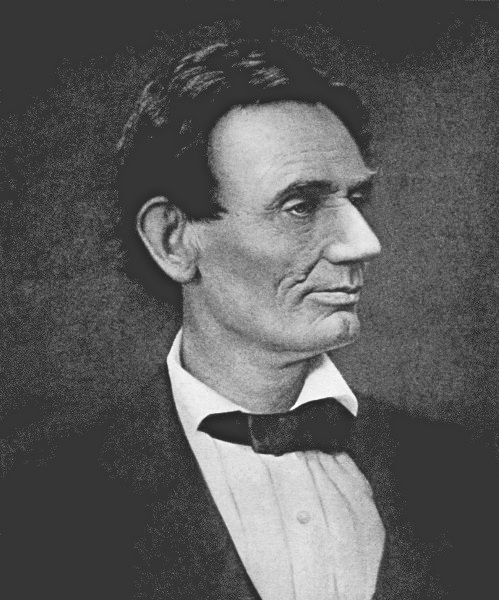

Lincoln won the Republican nomination because he was not too prominent and not too extreme, opposing the extension of slavery, but taking pains to point out that he had no intention of interfering with it in the slave states. That distinction meant nothing to Southerners. South Carolina made it clear that if a free-soil Republican were elected to the presidency, it would be cause for secession.

The election campaign was excited and noisy, though Lincoln spoke cautiously about the explosive issues he would face as president. Senator Seward swallowed his disappointment over losing the nomination and campaigned energetically for Lincoln. The Republicans danced around the issues, as did the other candidates, except for Stephen Douglas. He denounced "treason" from the stump with his foghorn voice, saying in a speech in Raleigh, North Carolina: "I am in favor of executing in good faith every clause and provision of the Constitution and of protecting every right under it -- and then HANGING EVERY MAN who takes up arms against it!"

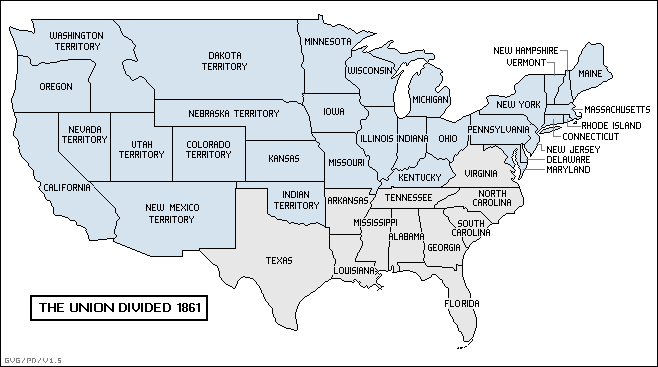

Election day was 6 November 1860. To no one's great surprise, Lincoln won, though with only 40% of the vote; he carried all the free states and none of the slave states. Republicans celebrated in the North, while Southerners railed at the new president-elect. The governor of South Carolina, William H. Gist, had been putting out feelers to other Southern states for the past month to see how much support South Carolina would have if the state seceded from the United States. The message was carried by his nephew, whose name, States Rights Gist -- called "States" by those who knew him -- suggested the importance of the principle to his family. The response seemed positive enough, and on 20 December 1860, South Carolina unilaterally left the Union. Voices rose for other states to secede from the Union and form a "Confederacy" that would unite them in their common aspirations.

In modern times, there are those who insist that secession had nothing at all to do with slavery. The declaration of grievances drawn up by the South Carolina legislature justifying secession were explicit in saying that it did, making a case for the Constitutional right of the state to secede, and citing at length the threats, both real and imagined, posed by the Federal government against the institution of slavery as the primary justification for secession. The word "tariff", incidentally, did not appear once in the declaration. The term "State's Rights" might not have been another phrase for "slavery", but the two were so intertwined as to be inseparable.

There was really only one state's right that people felt so strongly about that they were willing to risk war over it: the right to own slaves. The South had not attempted to confirm the legality of secession before taking the plunge, rendering any claims of its legality forever irrelevant. Southerners simply did what they felt was right -- but though it is certainly hard to judge them villains, they seceded for the sake of protecting slavery, and so nobody who opposed slavery could ever concede that they were in the right. To defend Southerners in choosing to secede, could only be defending their right to oppress the black folk they kept in chains.

* While the South moved toward secession, the Federal government began to consider what to do about it. The tiny US Army numbered only about 16,000 men, stationed mostly in the Far West to fight Indian tribes. It was currently under the command of Lieutenant General Winfield Scott.

By 1860, Scott had grown fat and increasingly feeble, but had not completely lost his edge. In early December, he had considered the military implications of secession and sent a rambling letter to President James Buchanan to suggest options. General Scott listed the military installations that would be at risk if the Southern states seceded, and pointed out that they were all unmanned or insufficiently manned. He suggested that they all be immediately brought up to full garrisons, though there were no forces available to do so. Scott further stated that if the Southern states seceded, there would be no hope of restoring the Union except by "the despotism of the sword".

This letter was remarkable in that it was unsolicited; totally outside the bounds of his authority as the commanding general of the Army; and in defiance of Scott's superior, Secretary of War John B. Floyd. President Buchanan was not happy with the advice. Buchanan was gentlemanly, not assertive nor decisive, and he was confronted with a crisis that was far outside of his experience, or for that matter the experience of any previous American president. His cabinet was split between Northerners and Southerners. Buchanan was a Northerner and a Unionist, but he was sympathetic to the South and found the idea of taking military action against other Americans repellent.

He was also a lame duck president. The election of Lincoln had put him into this fix; it seemed perfectly sensible and prudent to maintain the status quo and let Lincoln make the big decisions, without the encumbrance of actions taken by a previous administration.

The secession of South Carolina stepped up the pressure on Buchanan. The South Carolinans, having declared their independence, were now exerting pressure on the Federal government to hand over Federal institutions in the state. The major issue of concern was the fortifications in Charleston harbor.

The city of Charleston sits at the confluence of the Cooper River from the northwest and the Ashley River from the west. The two rivers flow into a large bay, which then empties into the sea. There were fortifications on both shores at the mouth of the bay: Fort Moultrie on the north, which was garrisoned, and Fort Johnson on the south, which was more or less abandoned and in a state of dilapidation. Between them, on an island, was Fort Sumter, which was still under construction and without a garrison. Deep within the bay, on another island at the mouth of the Cooper, was Castle Pinckney, also abandoned. Tensions had been rising over these fortifications for months, and in hopes of calming the situation, Major Robert Anderson had been sent to Charleston to take command of these installations.

Anderson was Kentucky-born, married to a Georgia woman, basically pro-Southern and pro-slavery. He was also a loyal and efficient Army officer, with the demeanor of a mild-mannered college professor, and was judged unlikely to antagonize the Charlestonians. The pressure still continued to build. On 26 December, Major Anderson concluded that an assault on his installations was imminent; in fact, one of Anderson's officers, Captain Abner Doubleday, believed that the only reason they hadn't been overrun was that the South Carolinans were waiting for the Federals to complete their work on Fort Sumter before seizing it. Anderson decided that he would have a better chance to hold out if he moved his command to Fort Sumter. That evening, he and his 68 men rowed quietly from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter past careless guard boats, spiking the guns left behind.

The South Carolinans were outraged, sending representatives to Washington to talk to President Buchanan and his people. There had been a series of such contacts over the previous weeks, with Buchanan wavering from conciliation to outbursts of anger, but nothing was decided one way or another. However, there had been a general reshuffling of the cabinet as Southern cabinet secretaries resigned, the result being that the cabinet had become more Unionist. The most prominent of the Unionists was the new attorney general, Edwin M. Stanton. Stanton was a prominent Washington lawyer, a fanatical Unionist with the personality of a noisy terrier. The cabinet meetings that followed the arrival of the latest representatives from South Carolina were chaotic. Buchanan was browbeaten from both sides, and reduced to a state of complete muddle.

Winfield Scott, in contrast, was not muddled at all. He had been out of the loop over the past few weeks, mostly due to bad health, and was getting frustrated over it. On 28 December, he sent a memo to his boss, Secretary of War Floyd, and copied the President, suggesting strongly that Fort Sumter should not be abandoned, and in fact it should be reinforced and resupplied under the escort of armed vessels. General Scott was a Virginian by birth, a Southerner -- but if the secessionists were talking about a fight, he was damn well willing to give them one.

The South Carolinans then managed to infuriate Buchanan by making further demands. He still held his judgement, and called a cabinet meeting the next day, 29 December, to discuss options. The result was a civil war in miniature, with Northerners and Southerners arguing loudly. Attorney General Stanton was outraged at the presumption of the South Carolina representatives, crying out stridently: "These gentlemen claim to be ambassadors. It is preposterous! They cannot be ambassadors -- they are lawbreakers! Traitors! They should be arrested!"

Stanton browbeat the President for dealing with the representatives, growing so wild that he told the President that if he gave up Fort Sumter, he would be the greatest traitor since Benedict Arnold and would deserve to be hanged. The Unionists in the cabinet finally won Buchanan over to their side. The President would not see the South Carolina representatives again, and he would not evacuate Fort Sumter. The representatives left Washington in a huff, leaving as a parting shot an overblown letter, which Buchanan officially rejected.

Winfield Scott was encouraged by Buchanan's shift to the Unionist position, as well as by his new boss, a die-hard Unionist named Joseph Holt. Floyd had got himself in trouble over some illegal business transactions with a government contractor -- the Buchanan Administration had suffered through a series of corruption scandals, with Floyd being one of the prime offenders, though some believe he was more incompetent than crooked -- and had been forced to resign his position as Secretary of War. Holt, who had been Postmaster General, took Floyd's place. On 30 December, Winfield Scott sent another letter directly to the President, politely suggesting the immediate reinforcement of Fort Sumter. Buchanan was now firmly against the secessionists, and the US government began to seriously consider what needed to be done to relieve Fort Sumter.

* In the meantime, Congress was in a degree of chaos following the exit of many of its Southern members. There was talk of patching things up, which finally congealed into the "Crittenden Compromise", put forward by Kentucky Senator John J. Crittenden in mid-December. Crittenden proposed that Congressional resolutions and constitutional amendments be implemented that would extend the Missouri Compromise line all the way to the West Coast, provide guarantees for slavery, and further tighten up the Fugitive Slave Law. In addition, the constitutional amendments would be perpetual; there would be no way to repeal them later.

The Crittenden Compromise was a non-starter. To no surprise Republicans, including Abraham Lincoln, saw it as a complete surrender to slave-owners, amounting to an extremely one-sided sort of "compromise". The idea of unrepealable amendments also seemed absurd to anyone who thought about it for long: if the Constitution could be amended, it could be amended to cancel any such guarantees, making them worthless on the face of it. Southerners who still remained in Congress did like the compromise, but in the absence of their secessionist colleagues they were outnumbered by the Republicans. Both the House and Senate rejected the Crittenden Compromise by the end of the month.

There were other proposals for a compromise that weren't so objectionable to the Republicans, but by the same token they were less acceptable to Southerners. In any case the secessionists, having taken the plunge, were not looking back, and it highly arguable that any sort of compromise could have lured them back into the fold. Senator Crittenden failed in his attempt to save the Union, and the failure would split his family: both his sons would become generals, one staying with the North and the other going South.

BACK_TO_TOP* By the new year, 1861, the Union was falling apart. Mississippi seceded on 9 January; Florida on the 10th; Alabama on the 11th; Georgia on the 19th; and Louisiana on the 26th. State legislatures passed resolutions generally along the lines of the South Carolina declaration of grievances, again prominently featuring Federal threats to slavery. Federal forts and arsenals, staffed only by caretaker detachments, were seized without a fight. Overenthusiastic citizens in North Carolina also seized two Federal forts, but were bluntly ordered by the governor to return them immediately. North Carolina hadn't seceded from the Union and, for the moment, had no plans to do so.

On 21 January, Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, long one of the arch-secessionists, gave his farewell address to the Senate. Davis was prone to violent headaches and had been ill with them for a week, but he delivered his speech, after a little faltering, with the directness for which he was well known. He said in essence that Mississippi had left the Union, and so he had no further business in Washington. He had loved the Union, but now matters had gone to the point where further discussion was useless. He hoped for peace, but said that if there were war, Mississippi's sons would stand "like a wall of fire around their state".

He wished his former colleagues well. His voice broke; women in the gallery wept; and then Jefferson Davis left Washington for Mississippi. His fellow cotton-state congressmen left along with him. With the Southerners gone, Unionists and particularly Republicans now dominated the US Congress. The first result of this was the admission of Kansas to the Union as a free state; they also quickly passed the "Morrill tariff", introduced by Congressman Justin Smith Morrill of Vermont, which sharply increased tariffs. The tariffs would be later adjusted further upwards.

The secessionist states were for the moment disorganized, and the border states remained undecided. A delegate from Mississippi addressed the legislature of slave-state Delaware, only to receive in response an "unqualified disapproval of the remedy for existing difficulties". There were few slaves in Delaware, the great majority of black folk living there being freemen, and there was no great liking for the idea of secession.

Pro-slavery elements in Maryland tried to persuade Governor Thomas B. Hicks to call a special session of the legislature to consider secession. The Unionist Hicks flatly turned them down. North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Missouri were sympathetic to secession, but cool to the idea of leaving the Union for the moment. Arkansas secessionists took over the Little Rock arsenal after the Federal commander abandoned it to avoid bloodshed, but the state did not secede from the Union.

Virginia was the most prestigious and influential of the Southern states: if Virginia left the Union, it would be a great boost to the secessionist cause. However, there was substantial Unionist sentiment in the state, particularly in the mountainous western counties, and there was no immediate drive to secede -- though the state legislature warned the Federals that Virginians would not tolerate the use of force against their fellow Southerners.

In Texas, Governor Sam Houston told his secession-leaning legislature:

QUOTE:

Let me tell you what is coming ... Your fathers and husbands, your sons and brothers, will be herded at the point of a bayonet ... You may, after the sacrifice of countless millions of treasure and hundreds of thousands of lives, as a bare possibility, win Southern independence ... But I doubt it. I tell you that, while I believe with you in the doctrine of States Rights, the North is determined to preserve this Union. They are not a fiery, impulsive people as you are, for they live in colder climates. But when they begin to move in a given direction ... they move with the steady momentum and perseverance of a mighty avalanche.

END_QUOTE

Houston was deposed from the governorship, and Texas left the Union on 1 February 1861.

* The states that had left the Union wasted little time in setting up a government. Delegates from the six breakaway states met in Montgomery, Alabama, on 4 February to discuss the organization of a provisional government, which was duly formed on 8 February 1861. Two days later, Jefferson Davis received a telegram at his plantation at Brierfield, below Vicksburg, Mississippi, telling him he had been appointed President of the Provisional Government of the Confederate States of America.

Davis left the next day for Montgomery, for the moment the capital of the CSA. He was inaugurated on 18 February, with Alexander Hamilton Stephens becoming his vice-president.

The provisional constitution of the new nation was closely modeled on the old US Constitution, though it explicitly gave the Confederate president a six-year term; granted each member of the president's cabinet a seat in Congress; and banned tariffs as a protective measure, though it allowed them as a source of government revenue. Surprisingly, not much was said about State's Rights, but very significantly the constitution guaranteed slavery, in section 9.4: "No bill of attainder, ex post facto law, or law impairing the right of property in negro slaves shall be passed."

Davis and Stephens were not well matched, and would not get along. Davis selected cabinet secretaries from all seven Confederate states to ensure that all the states would have a voice. The secretaries were prominent men from the well-bred, conservative, and respectable Southern power elite, most of them having opposed secession. The noisy secessionist extremists, the "fire-eaters", were not going to be at the forefront. Now the Confederacy had a government. It was, to be sure, a government that at the moment had few resources at its command and no bureaucracy to administer them if it had, and which no other government recognized as legitimate.

* On 11 February 1861, the same day Jefferson Davis had left for Montgomery, Abraham Lincoln had left his home in Springfield, Illinois, on a private train that would take him to Washington DC, with the train making stops for speeches along the way. The very last stage of the journey became a petty fiasco. To get to Washington DC, Lincoln had to transfer trains in Baltimore, and to get to the station for the Washington train, he had to travel through Baltimore's city center. There were rumors of a conspiracy to assassinate him as he went through the city, and so he went through at night -- wearing a cloak and a soft cap instead of his usual stovepipe hat. The newspapers got wind of the tale, and played him up as cowardly.

Lincoln had only nine days to get ready for office and was very busy. He had to form a cabinet, deal with a horde of office-seekers, and most importantly consider what to do about the secession crisis. There was in fact a convention in progress on that matter at Williard's Hotel. None of the states that had seceded sent delegates, and those in attendance were respected but elderly statesmen. A newspaper unkindly described them as "political fossils". It was an exercise in futility, but Lincoln gave them the courtesy of a visit in late February. He was direct, asserting that he intended to support "obedience to the Constitution and laws". Southerners and their sympathizers simply responded with complaints.

Lincoln's main efforts were focused on assembling his cabinet. Senator William H. Seward was slated to become Secretary of State, while Secretary of the Treasury was to be Salmon P. Chase. The Attorney General would be Edward Bates of Missouri, while the Postmaster General would be Montgomery Blair of Maryland, from the politically influential Blair family. The Secretary of the Navy would be Connecticut's Gideon Welles, a bright, competent, and irritable man who had defected from the Democrats to the Republicans. The Secretary of the Interior would be Caleb Smith of Indiana, and the Secretary of War would be Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania. The two were there because of deals, and Lincoln had no real confidence in them.

Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated on 4 March 1861. It was a cold, gray, windy day, and sharpshooters stood on top of buildings and at windows to ensure that there would be no trouble. There was none. By a famous accident, when Lincoln removed his stovepipe hat to take the oath from ancient Chief Justice Roger Taney, Stephen Douglas happened to be at his side; seeing that Lincoln had no place to put his hat, Senator Douglas chose to be gallant, saying: "Permit me, sir." Douglas held Lincoln's hat through the rest of the ceremony. A witness commented: "Doug must have reflected pretty seriously during that half hour, that instead of delivering an inaugural address from the portico, he was holding the hat of the man who was doing it."

In his inaugural address, Lincoln firmly rejected the constitutional legitimacy of secession:

QUOTE:

I hold that, in contemplation of universal law and of the Constitution, the Union of these States is perpetual. Perpetuity is implied, if not expressed, in the fundamental law of all national governments. It is safe to assert that no government proper ever had a provision in its organic law for its own termination ...

It follows from these views that no State upon its own mere motion can lawfully get out of the Union; that Resolves and Ordinances to that effect are legally void; and that acts of violence, within any State or States, against the authority of the United States, are insurrectionary or revolutionary, according to circumstances.

END_QUOTE

As far as he was concerned, the Union was "unbroken", and he would continue to "hold, occupy, and possess the property and places belonging to the government, and to collect the duties and imposts." He continued to identify the source of the troubles between the South and the North:

QUOTE:

One section of our country believes slavery is right, and ought to be extended, while the other believes it is wrong, and ought not to be extended. This is the only substantial dispute.

END_QUOTE

He rejected the idea that it was a state's own business if it wished to withdraw from the Union; it was, on the establishment of the Constitution, the business of the entire Union. He saw it as much like members of a household trying to wall off their part of the house against the wishes of the other members. The rest of the household had every proper reason to object: "Physically speaking, we cannot separate. We cannot remove our respective sections from each other, nor build an impassable wall between them."

To Lincoln, secession represented the destruction of an experiment in democracy created by the Founding Fathers. It was the shattering of an America whose power over his own lifetime had been going from strength to strength, a nation that could increasingly look the monarchies of Europe in the eye, into a fragmentation of bitterly squabbling little states. He did end with a plea:

QUOTE:

My countrymen, one and all, think calmly and well upon this whole subject. Nothing valuable can be lost by taking time. If there be an object to hurry any of you in hot haste to a step which you would never take deliberately, that object will be frustrated by taking time; but no good object can be frustrated by it.

In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the government, while I shall have the most solemn one to "preserve, protect, and defend it."

I am loathe to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

END_QUOTE

The Capitol building behind him was incomplete, with no dome over the unfinished rotunda. Some had suggested that work be halted for the duration of the crisis, but Lincoln had ordered it to continue, and commented: "I take it as a sign that the Union will continue."

The inauguration over, Lincoln went to work in his new residence. Outgoing President Buchanan remarked that if Lincoln was as glad to get into the White House as he was to get out of it, he must be the happiest man alive. Buchanan retired to his home near Lancaster, Pennsylvania, to passively watch events unfold, dying there in 1868.

Some had no doubt there would be war, a big one. Back on Christmas Eve, the supervisor of the Louisiana Military Academy, William Tecumseh Sherman, was eating dinner with one of his professors when they received news of the secession of South Carolina. Sherman was from Ohio, 40 years old, and an ex-Army officer. He was thin, wiry, hyperactive, and exciteable. He paced the room and then gave his southern colleague an earnest lecture:

QUOTE:

You people of the South don't know what you are doing. This country will be drenched in blood, and God only knows how it will end. It is all folly, madness, a crime against civilization! You people speak so lightly of war; you don't know what you're talking about. War is a terrible thing!

You mistake, too, the people of the North. They are a peaceable people but an earnest people, and they will fight, too. They are not going to let this country be destroyed without a mighty effort to save it ... Besides, where are your men and appliances of war to contend against them? The North can make a steam engine, locomotive, or railway car; hardly a yard of cloth or pair of shoes can you make. You are rushing into war with one of the most powerful, ingeniously mechanical, and determined people on Earth -- right at your doors.

You are bound to fail. Only in your spirit and determination are you prepared for war. In all else you are totally unprepared, with a bad cause to start with. At first you will make headway, but as your limited resources begin to fail, shut out from the markets of Europe as you will be, your cause will begin to wane. If your people will but stop and think, they must see in the end that you will surely fail.

END_QUOTE

They did not stop and think. In February, Sherman resigned his position a the academy in despair and headed north. In late March, he arrived in Washington to see his brother, Ohio Senator John Sherman. John Sherman introduced William to the President as a credible witness to events down South. Lincoln asked Sherman: "Ah. How are they getting along down there?"

Sherman replied: "They think they are getting along swimmingly. They are preparing for war."

Lincoln said: "Oh, well, I guess we'll manage to keep house." Sherman judged the President a buffoon, and left Washington in disgust to find work in Saint Louis. His brother tried to persuade him to stay and take a commission as an officer in the Army, but Sherman blasted him: "You have got things in a hell of a fix, and you may get them out as best you can!"

BACK_TO_TOP* The Union and the Confederacy were not well matched as opponents. The census of 1860 showed the North had a population of 20 million, while the South had a population of 9 million, and of that population 3.5 million were slaves. The number of white males between the ages of 15 and 40 was about 4 million in the North versus 1.1 million in the South.

As William Tecumseh Sherman had pointed out, the South had a weak industrial and economic infrastructure. When the war started, only 10% of American goods were manufactured in the South. The North had 22,000 miles (35,400 kilometers) of railroad track, the South had only 9,000 miles (14,500 kilometers), and these Southern lines tended to be local feeder routes, disconnected from one another and using different rail gauges. The Southern economy was based on cotton exports, which made the Confederacy vulnerable to naval blockade, and the South lacked the financial resources needed for funding a serious war. The North was, at heart, an entrepreneurial, capitalist society, devoted to getting things done; the South was a mostly agrarian society, not strongly attached to commerce as a principle, and not liking a hurried lifestyle.

The South did have advantages. Many of the old US Army high command had been from the South, and the Southern clique had by accident or design driven promising Northern officers out of the prewar Army: at the outset, the Confederacy possessed the superior military leadership. Furthermore, the South was fighting on the defensive, which would help even the odds against a more powerful attacker by forcing him to assault entrenchments and fortifications.

Being on the defense had other advantages. An attacker would be reliant on long supply lines that would stretch and become more vulnerable to a counterstrike the further the invader drove into Southern territory, with railroad bridges particularly vulnerable to destruction. The invaders would also have to set aside troops to ensure control over occupied territory, reducing the size of offensive armies. In contrast, the Confederates would be able to move troops and supplies on shorter and more easily protected interior lines of communications, and could generally -- though, as it would turn out, not always -- assume a loyal populace.

There was also the more intangible asset of simple spirit: Southerners were more of a fighting people and would prove time and time again that they had an unmatched boldness, a willingness to take and dish out punishment; they would also prove extremely ingenious in making the best use of limited resources. The more enthusiastic secessionists thought that Southern spirit would carry the day in and of itself. After all, if Great Britain, the most powerful nation in the world in 1776, hadn't been able to subdue the ragtag Patriot forces of George Washington, how could the Yankees subdue the people of the South?

Sherman had recognized that fighting spirit, but added that all else was lacking. All the willingness to fight did not change the fact that the South was taking on a much more powerful adversary -- right next door, not an ocean away and reliant on sailing ships as Britain had been. The Confederacy also had serious inherent structural weaknesses, above and beyond the simple lack of material resources. In the first place, the Confederacy was based on the concept of State's Rights, which established a degree of disunity as a fundamental principle, ensuring by design a weak central government, and implicitly left the door unlocked to further secession and fragmentation in the future. State's Rights had already led the Southern leadership to take an extreme step, and in time some Southerners of influence would take the concept from the extreme to the ridiculous.

Another problem was that while Northern society could hardly be described as classless, Southern society looked downright medieval in comparison. There was the issue of slavery, of course: Southerners not only had to worry about the threat of Yankee aggression, they had to worry about the perpetual threat of a slave uprising. The first threat tended to magnify the second: if Southern whites were preoccupied with fighting the North, slaves might well see it as a perfect time to rise up themselves. There was also the fact that potential foreign backers were in principle anti-slavery, making recognition of the Confederacy politically tricky. Lincoln would exploit that particular weakness with great skill.

Slavery was actually only one aspect of the social stratification. The elite that led the Confederacy was only half a percent of the population, with the high-born forming an effective nobility woven together by intermarriage in their caste, and the South was a layer cake of class distinctions and snobbery. The slave-owners in general represented the upper classes; only a minority of Southerners actually owned slaves, no more than 37% of families even in the Deep South, and about 20% of families in the Upper South. The poor farmers and hill folk near the bottom of the Southern social order were often looked down on as white trash, hardly better than slaves.

The poor farmers and hill folk often had no use for slavery and the contemptuous social elite that kept slaves, but not all the "lower orders" were hostile to the system. It was common to see those who owned large numbers of slaves as a social elite; admired or resented, the big slave-owners represented an ideal of power and influence to which the ambitious among the poor could aspire. More generally, the poor recognized that anti-slavery agitation opened the door to the dreaded possibility of "nigger equality", which would both elevate the one class to which they were superior, and introduce competition for their meager slice of the pie. This sentiment, not at all incidentally, was also widespread among poor whites in the North.

However, although secessionist agitators trumpeted the threat of black equality to rouse the citizenry, many of the poor Southern whites had a less cynical stake in the Confederacy. Most were sincerely not fighting for slaves or slavery, they were fighting out of a shared sense of proud Southern independence, against an aggressor who threatened their homes and families. After the war was well under way, a captive rebel private was asked what he was fighting for. He replied: "I'm fighting because ya'll are down here."

BACK_TO_TOP* Despite Lincoln's stated intent to hold Federal installations in the seceding states, nearly all of them had been taken over by secessionists without a fight. Besides Fort Sumter, two forts in the Florida Keys still remained in Federal hands, being too remote and isolated to be affected by the trouble, as well as Fort Pickens, outside the harbor of Pensacola, Florida. Although the Confederates had their eye on Fort Pickens, it was easily resupplied and defended; after a little indecision, the fort was reinforced, and would remain in Union hands through the rest of the conflict.

Fort Sumter was the real issue. In the months leading up to Lincoln's inauguration, the Buchanan Administration had been considering different options, and taking hesitant steps to relieve the fort. A steamer named the STAR OF THE WEST had in fact been sent with supplies for the besieged installation, but when it entered the harbor on 8 January 1861, the Confederates fired warning shots. On the ramparts of the fort, Major Anderson ordered his own men to hold their fire; the steamer's captain decided to turn about and leave the way he had come.

The South Carolinans had been steadily building up the shore installations to bring more guns to bear on Sumter in order to prevent it from being resupplied. South Carolina Governor Francis W. Pickens, who had in the meantime replaced William Gist in that office, persistently nagged the new Confederate government for assistance. Pickens got more help than he bargained for. Jefferson Davis was no hothead, tending in fact more towards the frosty; he didn't think much of hotheads, and finally simply told Pickens that the Confederate government had taken control of the matter. Davis sent an officer of the new Confederate States Army, General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, to command the military effort to ring in Fort Sumter.

Beauregard was from Louisiana and his first tongue was French. He was a dapper fellow who brushed his hair forward at the temples, and had aristocratic manners that pleased the Charlestonians. He also had a towering ego, but his polish kept it from being too great an irritant, and his military professionalism, particularly in artillery and engineering, was beyond dispute. On his arrival in Charleston in early March, he set about reinforcing and reorganizing the shore batteries to bring them up to combat readiness.

Back in Washington, even General Scott was having second thoughts about making war on the states in secession, suggesting they might well be left to go their own way in peace. Others were making the same suggestion, claiming that secession was just a bluff to gain concessions for the South, and that once the bluff was called, the South would come back into the fold of the Union.

Lincoln's cabinet was against making hostile moves, with the reluctance aggravated by General Scott's doubts. On 29 March, Lincoln read a note from General Scott to the cabinet. The general suggested that both Fort Sumter and Fort Pickens be abandoned to placate the border states. The President was sounding out his people, and they gave him the response he wanted: after a shocked silence, the response was still overwhelmingly in favor of standing ground, though there was disagreement over the specifics.

Within a few days, Lincoln had made up his mind. Some of the plans for resupplying Fort Sumter involved quietly slipping a civilian transport into Charleston harbor at night so that it might reach Fort Sumter without being fired on. Lincoln, drawing on his lawyer's cleverness, decided that Fort Sumter would be resupplied -- and then informed the South Carolina authorities of this decision on 6 April. He made it clear that he had no intention of sending in more troops or initiating violence.

Lincoln had properly understood the logic of the situation; he had changed the question from what the Union would do, to what the Confederacy was going to do. The South had unilaterally decided to reject Federal authority, but that was in itself a mere expression of principle. It ceased to be a mere expression of principle if the South then resorted to force to interfere with the workings of the Federal government. After all, if a citizen proclaimed he wasn't going to obey the laws, that was one thing; if he then took shots at police officers carrying out their duties to drive them off, that was very much another. If the Confederates let the resupply effort pass, they would be conceding to Union authority; if they fired on it, that would be treason.

In hindsight, had the Confederacy adopted a program of passive resistance to Federal authority, it would have demanded extreme patience to carry out, but -- as President Lincoln broadly realized -- it would have placed the government in Washington in a very difficult position. If the citizens of a state had collectively refused to cooperate with the Federal government, the government would have had to militarily occupy the state indefinitely. Use of force to compel obedience in the face of widespread and persistent nonviolent resistance would have discredited Lincoln's government. It would have been entirely impractical to arrest all the disobedient if they steadfastly refused to submit; and to the extent that people were arrested, the trials would have also discredited the government, with court proceedings providing a high-profile stage for secessionist theatrics.

The South might have let the supplies go through to Fort Sumter, stalled for time, and gradually wearied the crisis to death. However, few if any Southerners were in favor of a program of nonviolent resistance, indeed it's hard to find any mention of it; Jefferson Davis certainly was not considering that option. In his view, the Confederacy was an independent nation, and would assert its authority as one. He would take action against Fort Sumter. Treason? The Confederacy was an independent nation, and would conduct itself as one.

Confederate Secretary of State Robert Toombs, who had been among the "fire-eaters", saw the folly of this course of action, telling Davis: "Mr. President, at this time it is suicide, murder, and will lose us every friend at the North. You will wantonly strike a hornet's nest which extends from mountain to ocean, and legions now quiet will swarm out and sting us to death. It is unnecessary; it puts us in the wrong; it is fatal."

Davis was determined to go ahead. On 10 April, instructions were wired to General Beauregard to demand the evacuation of Fort Sumter, and to reduce it by force if the demand wasn't met. On the morning of 11 April, General Beauregard wrote Major Anderson a polite and formal letter, demanding that the Federals evacuate Fort Sumter. Major Anderson wrote an equally polite and formal reply, indicating that he could not comply. However, as the Confederate officers carrying the correspondence prepared to return to shore, Anderson blurted out: "If you do not batter us to pieces, we will be starved out in a few days." This nervous remark led to a flurry of messages, but Anderson still did not intend to abandon the fort, and the Confederate ultimatum was not withdrawn.

In the early hours of the next morning, Beauregard sent a letter to Anderson informing him that he would be fired on within the hour. At 4:30 on the morning of 12 April 1861, the first signal shot was fired from a mortar and exploded over Fort Sumter. The shot was fired by Edmund Ruffin, a die-hard long-time secessionist "fire-eater" from Virginia. Back in Charleston, Mary Boykin Chestnut, a prominent citizen who would keep a detailed diary through the coming years of struggle, wrote: "April 12 ... The heavy booming of cannon -- I sprang out of bed, and on my knees, I prayed as I have never prayed before."

The shelling went on all that day, went mostly silent that night, and resumed in the morning. The Federals were unable to offer more than token counter-fire. On the 13th, after 34 hours of bombardment, Anderson capitulated. The Sumter garrison formally surrendered on Sunday, 14 April 1861. Anderson's men were allowed safe passage out of South Carolina on a steamer, and took down the Stars & Stripes in a formal ceremony. Anderson kept it so that he could be buried in it. Beauregard obtained a walking stick made from part of the flagpole as a souvenir.

During the firing of a cannon salute at the surrender ceremony, a spark fell on powder and set off an explosion, killing one Union man outright, mortally injuring another, and wounding three more. They were the only casualties of the Fort Sumter bombardment. However, a conflict had been set in motion whose destructiveness could not then be imagined. The North would now take on the Confederacy and bring immense force to bear on it. Southerners would later brand this pure aggression, and a case can be made that it was, but Lincoln had played his cards well: there would never be any way to deny that, in the face of a confrontation on the edge of explosion, the Confederacy had shot first.

It is difficult to believe that there wouldn't have been war eventually. In states such as Kentucky and Missouri, where the populations were divided in their sympathies, secession was likely to lead to clashes, and clashes were likely to lead to confrontations between the Union and the Confederacy. The Confederacy also had ambitions for territorial expansion to the West, which would have also led to a fight with the Union. The creation of the Confederacy meant, as far the Federal government was concerned, the establishment of a rival foreign power on American soil, with ambitions antagonistic to Union interests. The house divided against itself implied confrontation.

However, history is not a controlled experiment, there's no way to know what would have really happened had events gone differently. The fact is that the shooting started with the bombardment of Fort Sumter. It is hard to believe that those who gave the order to fire weren't intelligent enough to realize that it meant war. The only explanation for why they did is that they thought, in defiance of all measures of material strength, that they would prevail.

Southerners would long blame the North for its war against the South; but though they would damned if they'd admit it, as much or more blame might be placed on Southern leadership for taking their people over the precipice in a fit of hysteria. Yes, the Union response was drastic, but was secession was a drastic measure itself -- more drastic and reckless than can be easily appreciated when it is beyond living memory -- and it left the Union with no alternatives except to cave in, or fight to win with as much savagery as needed to do so.

* That Sunday, 14 April 1861, when the news reached Washington that Fort Sumter had surrendered, Lincoln met with his cabinet, and on Monday issued a proclamation requesting 75,000 militia to serve for 90 days to deal with "combinations too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings."

Just as secession had been accompanied by a burst of stored-up energies in the South, the call for militia released an outpouring of patriotism in the North. Young men rushed to sign up with state militias, and upper-class citizens who had been in militias as little more than a social function prepared their kits for battle, though their choice of gear was sometimes a little too luxurious for practical use. Militia regiments were formed out of locales and communities, and in many cases the militiamen had grown up together, sometimes being brothers or even fathers and sons. There were Irish regiments, German regiments, and Italian regiments; in some cases, many enthusiastic Unionists rallying to the colors could barely speak English.

Although Northern women would of course not form up combat regiments, they banded together to create a volunteer organization to help support the troops, mostly with medical services. While US Army bureaucracy was not all that helpful to the women, their organization would be legally endorsed by the President in June as the "Sanitary Commission", which would become a significant actor in the conflict. The Sanitary Commission's efforts would be complemented by that of the United States Christian Commission, set up by the Young Men's Christian Association; the Christian Commission's work was oriented towards providing Bibles and other religious materials, but it also provided a degree of material assistance to the troops.

Lincoln and many others believed there was substantial Unionist sympathy in the South, that the secessionists were simply a militant minority who had hijacked Southern state governments, and forcing the issue would bring these patriots to the surface. He was wrong. The bombardment of Fort Sumter had roused enthusiasm for secession in the Upper South, and the call for militia made the deepening split between North and South complete. On Wednesday, 17 April, Virginia's secession convention, which was still in session, passed an ordinance of secession. The next day, the Virginians gathered around the Federal armory at Harper's Ferry. That night, the Union commander had his men torch the arsenal and armory, and led them north into Pennsylvania; the rebels managed to save much of the machinery and haul it off to Richmond. The Union did retain control over Fortress Monroe, on the tip of the James River peninsula east of Richmond.

When Lincoln issued the militia proclamation on Monday, North Carolina militia seized Federal installations. The state would not formally join the Confederacy until 21 May, but that was no more than paperwork. Similarly, Tennessee took measures that by the first week of May had effectively removed it from the Union, and on 6 May Arkansas passed an ordnance of secession.

Many Southern-born US Army officers turned in their resignations, and went home to become Confederate officers; one out of three left. The Army's Quartermaster General, Joseph E. Johnston, was from Virginia and felt he had to leave. He said graciously in his resignation: "I must go with the South, though the action is in the last degree ungrateful. I owe all that I am to the government of the United States. It had educated and clothed me with honor. To leave the service is a hard necessity, but I must go. Though I am resigning my position, I trust I may never draw my sword against the old flag."

Johnston's resignation was a loss to the US Army. He was a neat, small man, bald with a trim goatee, given to a certain liveliness, military competence, and a marvelous kindliness to those in his command. The loyalty of another Virginian officer, the highly regarded Robert E. Lee, was a matter of greater concern to the US War Department. Winfield Scott regarded Lee as the best officer he had, and on 17 April Lee received an offer passed down from President Lincoln for command of the entire Union Army. Lee believed in the Union and cared little for talk of secession -- but after Virginia joined the Confederacy, he felt he had no choice but to go South. He could not take military action against his home state, and on 23 April Lee accepted high rank in the army of Virginia.

Southerners signed up to fight the Yankees with enthusiasm that mirrored that shown in the North. Southerners wanted to protect their homes against invasion; they felt they could easily whip the soft and cowardly merchants and factory workers of the North. Mary Chestnut wrote of the soldiers crowding into Charleston: "They fear the war will be over before they get a sight of the fun. Every man from every little county precinct wants a place in the picture." Both sides thought they would win easily: the war would be over in less than 90 days.

BACK_TO_TOP