* The outbreak of war between North and South left Washington DC in a precarious, with Maryland wavering between the sides and no Union forces in the city to defend it. Maryland was brought under control, and the troops arrived. Both sides built up their armies, leading to an initial clash at Bull Run Creek, near Manassas in Virginia. The ramshackle battle led to a defeat for the Union, but the Confederates were in no position to follow up. The two sides settled in for a longer war.

* The notion of secession was less than simple in states where the citizens were of strongly divided opinions on the idea. After the second wave of secession, four states remained in the balance. Delaware was a slave state, but not a great problem, since there were few slaves there and no general interest in leaving the Union. Missouri was much more polarized, but thinly populated and not of immediate strategic importance. Kentucky was a greater fear, since a Confederate Kentucky would almost cut the Union in half; Lincoln was to say a little later that to lose Kentucky was essentially to lose the whole game.

The biggest immediate worry was Maryland. Washington DC was bordered by Confederate Virginia to the south and an unstable Maryland on the other three sides, as well as infested with secessionist sympathy from within. If Maryland joined the Confederacy, the city would be certainly lost.

Military forces with enough strength to hold Washington were slow to arrive. After the request for militia on Monday, 15 April 1861, a company of regulars from Minnesota and a few hundred Pennsylvanians came into town on the train on 18 April. They had been harassed and stoned by a secessionist mob while passing through Baltimore.

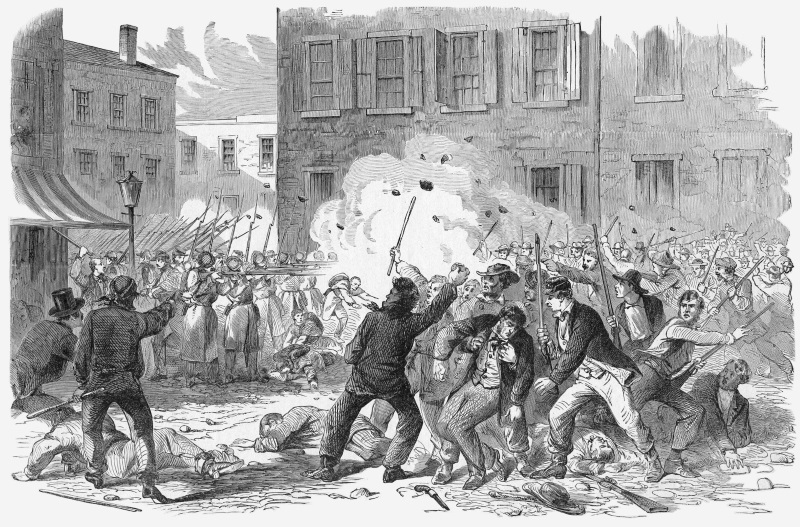

The next day, 19 April, the 6th Massachusetts Regiment marched through Baltimore to make the connection to Washington, and ended up having a shootout with the mob. Four soldiers were killed and 31 wounded; 12 citizens of Baltimore were dead, along with an unknown number of wounded. Many of the civilians who were shot were innocent bystanders who had been caught in the crossfire when the shooting began. The injured Union soldiers were met by a group of women, led by a Patent Office clerk from Massachusetts, Miss Clara Barton. She was a quiet spinster, but her sympathy with the men from her home state overcame her timidity. The others were barracked in the unfinished Capitol building, where they made good use of congressional franking privileges to write free letters home.

Maryland Governor Hicks expressed his fears over the provocation of funneling Union soldiers through Baltimore to the President, who responded that he understood and would try to avoid trouble. However, when a Baltimore delegation protested the movement of soldiers across any part of Maryland, Lincoln bluntly replied: "Our men are not moles, and cannot dig under the earth. They are not birds, and cannot fly through the air. There is no way but to march across, and that they must do." Lincoln then pointedly added: "Keep your rowdies in Baltimore, and there will be no bloodshed. Go home and tell your people that if they do not attack us we will not attack them; but if they do attack us, we will return it, and that severely!"

Baltimore secessionists took him up on his challenge, burning the railroad bridges connecting the city to Washington and then cutting the telegraph lines. Panic started to run through the streets of Washington as rumors of large Confederate forces gathering outside the city ran wild. Days passed, and the regiments of troops that Lincoln had been promised didn't materialize. He paced his office, muttering: "Why don't they come? Why don't they come?" On reviewing some of the men of the 6th Massachusetts who had been wounded in the fight in Baltimore, he told them: "I don't believe there is a North ... you are the only northern realities."

* That wasn't the end of the bad news. On 23 April, two Union vessels docked at Washington DC, relaying the bad news that the Gosport Navy Yard, at Norfolk in Virginia, had been abandoned to the Confederates. The commander there, 68-year-old Commodore Charles S. McCauley, had feared the Confederates were going to seize the base, and pulled out on the evening of 19 April, putting it to the torch. That was particularly ironic, because on that same day, 19 April, Lincoln had declared a blockade of the Confederacy, though he lacked naval forces to implement it -- to immediately find he had lost a substantial part of what he did have.

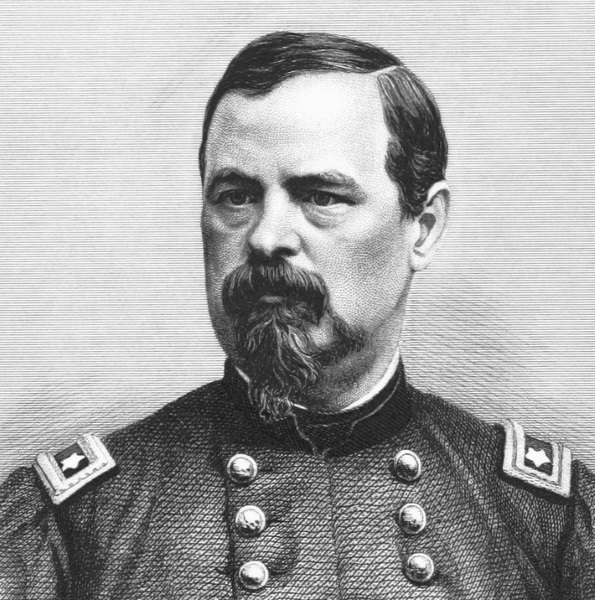

Finally, reinforcements started to flow into Washington. On Saturday, 20 April 1861, a steamer carrying the 8th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment had anchored at Annapolis, directly to the south of Baltimore. Maryland secessionists had sabotaged the rail lines out of Annapolis to block the movement of Union troops, but they had not reckoned on the commander of the 8th Massachusetts, Brigadier General Benjamin Franklin Butler.

Butler's commission as a brigadier general was from the state of Massachusetts, not the US Army. The states had the right to appoint officers to the militia without regular army approval or any military qualifications on the part of the appointee. The appointments were often for political reasons, and some of the officers had no real military background.

Ben Butler had been a prominent Democratic politician before the war, and it was useful for a Republican administration to have him on their side. In other ways, he was an uncertain asset. Butler was trusted by few, often described as "fat", "cross-eyed", "bandy-legged", and "shifty". He had an instinct for theatrics and tyranny, and a dubious instinct for military matters. He was also a shrewd and energetic politician who was not burdened by much in the way of high principles. One grudging admirer described him as an "only too successful cross between a fox and a hog."

Though Governor Hicks threw the same objections at Butler that Hicks had thrown at Lincoln, Butler blustered right over Hicks and had the 8th Massachusetts ashore by Monday, 22 April. The 7th New York Regiment arrived the same day, and Butler assumed command of it as well, though the regiment's officers protested loudly.

The 8th Massachusetts was full of mechanics; Butler quickly put them to work repairing the damaged rail line. Since the only locomotive available was out of commission, they repaired that as well. One Massachusetts soldier had actually helped build that particular engine. They were also assisted in their work on the railroads by a crew from the Pennsylvania Railroad that included an enterprising young Scotsman named Andrew Carnegie, who was to drive the repaired train on its first run. Butler deployed two companies of infantry to discourage further sabotage, and on Thursday, 25 April -- ten agonizing days after the call for militia -- the 7th New York rolled into Washington on the train, followed by 1,200 Rhode Island militia and an equal number of volunteers from Massachusetts.

By the end of April, there would be 10,000 troops in Washington, and the immediate threat would be over. The secessionist troublemakers in Baltimore were then dealt with On 27 April, Lincoln informed General Scott that the general had the authority to suspend the writ of habeas corpus along the military supply line between Philadelphia and Washington. Ben Butler marched his men into Baltimore from Annapolis in the first days of May, and proceeded to impose a strong-arm military dictatorship on the city, with Butler throwing anyone he wanted into jail.

General Scott had not authorized the occupation of Baltimore, and didn't like a politician in uniform like Butler anyway; in mid-May, Scott transferred him to command of Fort Monroe. However, the departure of Butler didn't mean a more relaxed state of affairs in Baltimore; the arbitrary arrests continued. When Chief Justice Taney objected to the arrest of a secessionist named John Merryman, Lincoln simply shrugged the objection off -- with good reason, the Constitution giving the President extraordinary powers in times of rebellion.

Such extralegal measures would be quickly extended throughout the Union, and secessionists and others judged subversive would find themselves in jail without the slightest pretense of due process. The Union had a war to fight; disloyal citizens were, as far as the Federal government was concerned, not going to get in the way. Traitors were going to be given the handling they deserved.

BACK_TO_TOP* While Maryland was being secured for the Union, the struggle for the border states of Kentucky and Missouri was just beginning to take shape. In such deeply divided states, the notion of secession was particularly, dangerously troublesome.

Governor Beriah Magoffin of Kentucky was secessionist, but the Kentucky legislature was not. Missouri Governor Claiborne Jackson was a devoted secessionist who had tried to take Missouri out of the Union earlier in the year, but had been shouted down by the voters. In both states, the two facts were arming and preparing for a showdown. Missouri represented a more immediate threat of secession, but Governor Jackson didn't reckon on US Army Captain Nathaniel Lyon -- an energetic hothead with backing from influential Unionists.

Lyon organized Unionist citizens of Saint Louis into a militia, then raided the city's armory to get them rifles -- those left over being quietly shipped to Springfield, Illinois, to ensure they didn't fall into secessionist hands. On 10 May, Lyon took his militia and confronted an encampment of secessionist militia outside the city; the secessionists gave up without a fight. However, when Lyon's militia took the prisoners back into the city for disarmament and parole, a riot broke out.

Dozens of people were killed that day and the next, with secessionists fleeing Saint Louis. Lyon didn't stop there, marching into Jefferson City on 14 June and driving the secessionist legislature from there. There was an indifferent clash between Lyon's troops and secessionist militia on the 16th, the secessionists pulling out. Lyon had seized control of Missouri for the Union.

* In the meantime, The Federal government was demonstrating considerable energy and focus on the political front. Getting the military front up to speed was not proving quite as easy. Back in early May, as the militia regiments poured into Washington, Lincoln had issued a new proclamation increasing the regular army by 20,000, the navy by 18,000, and asking for over 42,000 three-year volunteers. Now the question was of what to do with the added forces.

Winfield Scott could be muddled on occasion, but his military instincts were fundamentally sound. Scott had no faith in the capabilities of the 90-day militia, and the prospect of a large force of long-term volunteers meant he would have the resources to take a long view of the situation. On 3 May, he described his strategic vision in a letter to one of his generals. He would tighten the blockade around the South to cut off trade and foreign assistance to the Confederacy, and in the meantime send a force of 60,000 men, backed up by gunboats, down the Mississippi to cut the Confederacy off from Texan cattle and grain, as well as from any foreign resources that might trickle in across the Mexican border.

In time, possibly a year or two, the general thought, the rebellion would be choked out in a relatively bloodless fashion as hardship and boredom deprived it of its fire, and the Unionist sentiment that Scott believed, in the absence of much evidence, still remained in the South re-asserted itself. It would certainly be much easier and less brutal than trying to occupy all the Southern states and obtain their submission at the point of a bayonet. Such a "pacification campaign", as it would be called today, would be grinding and difficult.

Lincoln liked the idea, though Scott stated the big drive down the Mississippi could not begin before the middle of November. That was much too long for armchair warriors, who felt the rebellion could be crushed easily with one fast blow. When Scott's plan leaked to the press, it was roundly mocked as "the Anaconda plan", with cartoonists showing a huge snake coiling itself around the South. Some hotheads even called it treasonous. Such was the temper of the times.

The Union militia were eager to get into action. On 23 May, the citizens of the state of Virginia ratified the ordnance of secession, and as a safety precaution Lincoln ordered troops to cross the Potomac and seize Alexandria, Virginia. In the lead of the small force was Colonel Elmer Ellsworth of the New York Fire Zouaves, a regiment of New York rowdies mostly recruited from fire departments. Ellsworth was 24 years old, from an aristocratic New York City family, and a personal friend of Lincoln's. An Alexandria hotel was flying the flag of the Confederacy, and Ellsworth went upstairs to cut it down. On coming back down the stairs, the proprietor shot and killed him with a shotgun, and was immediately shot and killed in turn by Ellsworth's aide. Lincoln was crushed by the loss of his friend. Ellsworth's body lay in state in the White House and his colleagues grieved.

Ellsworth's death was a sign of things to come. Within a few days, there was another significant death that closed a chapter of the past. On 3 June 1861, Stephen A. Douglas died in Chicago at age 48, worn out from working too hard and drinking too much, breathing his last. He gave eerily reassuring words to those who in his company who had expressed the thought he was in great pain: "He ... is ... very ... comfortable."

Death was a comfort, since his last years had given him no peace. Since the war began, he had been a powerful voice for the Union, trying to bring undecided Westerners in with the Union cause, ruining himself financially and physically. A man whose life had been governed by pragmatism and self-interest died pursuing ideals and self-sacrifice. There were those in the South who felt the loss as well. Confederate Vice-President Alec Stephens thought Douglas should have died sooner or lived longer: had he died sooner, the Democratic split in Charleston in 1860 might have been avoided, and with his death there was no influential voice to restrain the use of force against the Confederacy by the Federal government.

* Although President Lincoln's belief that Unionist sentiment remained strong in the South was generally wrong, it wasn't completely so. The hill people of western Virginia, eastern Kentucky and Tennessee, and northern Georgia and Alabama owned few slaves and had little sympathy with the lowlanders. The region was rugged and somewhat inaccessible, which increased the sense of isolation the hill folk felt from the power centers in the cities. The rugged terrain also made military operations difficult, but the counties of western Virginia bordered Union territory and were more accessible to Federal forces.

However, rebel forces operating from the area also represented a threat to the main rail line from Washington to the west, the Baltimore and Ohio, went through Virginia territory, to connect to the Ohio Valley. The states of Ohio and Indiana had volunteer regiments available, these troops being placed under the direction of Major General George Brinton McClellan, commander of the Federal Department of the Ohio. When the Confederacy sent small forces into the region, McClellan marched his men in against them, sending the rebels fleeing after a skirmish at Philippi on 4 June.

In fighting over the next week, the Federals drove Confederate forces out of the region, much to the joy of Unionist citizens there. McClellan became the hero of the hour -- though it hadn't been much of an accomplishment, the Federals beating up on a weak opponent. Nonetheless, newspapers in the Union played up the victory.

In the meantime, the Unionist western Virginia counties had been conducting a series of meetings in the town of Wheeling, and by the end of June they had their own legislature in place, along with a governor, Francis Pierpont, and two senators to send to Washington. Since the Federal government regarded the secession of Virginia as illegal, the effective secession of the state's western counties from Virginia was in turn of highly doubtful legality as well; the measures were taken on the interesting theory that the secessionist state government no longer had any legal standing, and so the new government was the "true" state government. Washington agreed.

This was all unprecedented and thoroughly irregular -- but once more, since the rules had been abandoned, there was nothing to prevent them from being selectively applied. The Federal government recognized the governor and senators designated by the new state legislature as the "legitimate" officials of the state of Virginia and admitted their senators into the US Senate. For the rest of the year, through the next, there was an extended session of local politics and elections to put the establishment of the new state on a recognized legal basis.

After the war, the state of Virginia would formally concede the legal propriety of the formation of West Virginia. That was later; at the time, there was still some Confederate sympathy in the region and that would lead to a nasty guerrilla war, with neighbors fighting neighbors in cycles of reprisals. Farther south in the hill country, the Confederate government sent in forces to make sure the hill Unionists stayed in line.

* The militias that had arrived in Washington had saved the city, but they were Sunday soldiers, not real warriors. 43-year-old Brigadier General Irvin McDowell was put in charge of turning them into an effective combat force. McDowell was an odd figure. He was a reasonably competent and conscientious officer, with a good record in staff positions. He had received military training in France and wore a neat triangular beard in the French style. He was a stout man, who combined a prim aversion to tobacco and alcohol with a gluttonous appetite that appalled those around him. He was charmless, tactless, and overbearing, and gave offense for little reason to almost everyone he met. These were not the makings of a commander who would endear himself to his troops -- and who did not care if he did or not.

McDowell did understand that his motley soldiers were not in shape to fight a real battle. He told Lincoln: "This is not an army. It will take a long time to make an army." Lincoln replied: "You are green, it is true, but they are green, also; you are all green alike." The original volunteers had only signed up for 90 days and time was running out. Action needed to be taken soon.

There was something to be said for moving quickly in war with minimal preparations. On the other hand, there was a certain minimal level of competence required before any sort of action could be undertaken at all, and it was very uncertain that the Union army had even that modest amount of skill. To some observers, the Lincoln Administration's push to action seemed rash. William Howard Russell, a war correspondent for the TIMES OF LONDON who had seen battle in the Crimea and India, commented of Lincoln and his people: "They think that an army is like a round of canister, which can be fired off whenever the match is applied."

On the other hand, some enthusiastic Unionists thought Lincoln and his men much too timid. Horace Greeley, the exciteable and erratic editor of the NEW YORK TRIBUNE, fired a barrage of editorials at the White House demanding action, under the bold slogan: ON TO RICHMOND! ON TO RICHMOND!

In fact, while Lincoln may have been hopeful that the Confederacy would fall over at the first push, he wasn't counting on it, as he made publicly clear early in July. The first session of the 37th Congress of the United States met in Washington on Thursday, the 4th of July 1861, having been called to special session by the President after the fall of Fort Sumter. 80 days grace had been provided to the President to conduct military actions as he saw fit, and now the time was up.

With all the secessionist fire-eaters gone, Congress was no longer the place it had been. A newspaper editor wondered: "What will our New England brethren do without an opportunity of denouncing the peculiar institution in the presence of its devotees?" There were actually still a few congressmen present defending State's Rights and slavery, the most prominent of them being John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, who many regarded as being a de facto agent of the Confederacy. Another was a Democratic congressman from Ohio named Clement Laird Vallandigham, who attempted to introduce measures to send commissioners along with the Union Army in the field to receive Confederate peace overtures, and to censure President Lincoln for measures taken by the administration before Congress had met.

Vallandigham's measures went nowhere. The Republicans now had complete control of both houses of Congress. Of the 48 senators, 32 were Republicans, and of the 176 representatives, 106 were Republicans. The House quickly elected a pro-war speaker, Galusha Grow of Pennsylvania. New Englanders now controlled the four powerful Senate committees that influenced war policy. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts -- returned from Britain, still scarred from the murderous caning given him by Senator Brooks, and now by all appearances even more extreme in his hatred of the slave power -- was chairman of Foreign Relations, and his colleague, Henry Wilson, presided over Military Affairs. John P. Hale of New Hampshire was in charge of Naval Affairs, and William P. Fessenden of Maine led the Finance committee.

These men and their associates, most prominently Senator Ben Wade of Ohio and Senator Zachariah Chandler of Michigan, were all "Radical Republicans", determined to punish the South and put an end to slavery once and for all. In the House, clubfooted old Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, a bitter enemy of the South and its "peculiar institution", ran the powerful Committee on Ways and Means, which exerted control on government appropriations. When the secessionists had washed their hands of further discussion and walked out of Congress, they had shifted power there over to the South's worst enemies, people every bit as one-sided and extreme in their way as the secessionist fire-eaters, and the Radical Republicans were determined to make the most of the opportunity they had been given.

* On the first day of the 37th Congress, 4 July, President Lincoln addressed the body in a joint session. The president listed the actions he had taken on his own authority: he had called up the militia; declared a blockade of the Confederacy; increased the regular military forces; suspended the writ of habeas corpus; and committed the government to great expenditures. All that had been done without Congressional approval, and Lincoln needed that approval to proceed further.

He justified his actions by citing recent events: secession; seizure of Federal property; attacks on Fort Sumter, Harper's Ferry, and Norfolk; and the creation of an "insurrectionary government"; all these being actions intended to nullify Federal authority. Lincoln expressed his intent to confront the rebel government, as well as to recognize the new Unionist state government in western Virginia as the legitimate authority for that state. He denied the right of secession, and denied that the border states had a right to be neutral. Neutrality, he said, was "treason in effect", just another exercise in state defiance of the Federal government. This last remark clearly meant Kentucky; Lincoln was not being as cautious as he had been, since Congressional elections in that state on 30 June had revealed the Kentuckians were more loyal Unionists than not. There would never be any rush to secession in Kentucky.

Then the president dropped his bombshell: he requested 400,000 soldiers and $400,000,000 in funds to prosecute the conflict. Lincoln clearly expected a hard war. Finally, Lincoln expressed his hope that the Unionist majorities he believed, though the evidence in support was so far lacking, were lying quietly in the South would assert themselves, and spoke his belief that the Union could be reconstructed into an order directed by the Constitution and no different from that which existed before hostilities.

Reconciliation was unlikely; the Confederacy showed no signs of wanting it, and the mood of Congress was for war. The body did pass by an overwhelming majority a resolution proposed by Senator Andrew Johnson -- a tough east Tennessee Unionist who had stayed in the Senate, even though his state had left the Union, the only senator from a secessionist state to do so. Johnson's resolution stated that the war had been forced by Southern secessionists, and that the Federal government would prosecute the war simply to restore the Union and uphold the Constitution. The resolution stated there was no intent to either subjugate the South, or to interfere with slavery. However, Congress still supported the drastic steps Lincoln had taken, voting him the resources he requested, and resolutions providing reassurances to the South were meaningless in the face of measures taken towards making war on it. The polarization was irreversible.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Potomac River snakes along the border between the states of Maryland and Virginia, flowing in the west past Harper's Ferry, through the Blue Ridge Mountains, and southeast to Washington DC. Past the capitol, it turns southwest, and finally twists southeast again as it broadens to empty into Chesapeake Bay. Below the bend in the River south of Washington lies the city of Fredericksburg, on the Rappanhanock River, roughly halfway on a line between Washington and Richmond.

In 1861, Fredericksburg and Harper's Ferry were two ends of a semicircle with its center at Washington that defined the avenues open to the Federals for movements into northern Virginia. The Orange & Alexandria Railroad ran southwest through this arc, passing over the Bull Run River and through the rail junction at the town of Manassas. Confederate General Beauregard had about 23,000 men near Manassas to oppose McDowell's force of roughly 35,000 men. Another Confederate force of about 11,000 was beyond the Blue Ridge mountains, south of Harper's Ferry in the Shenandoah Valley, under the command of Brigadier General Joe Johnston. In theory, Johnston was there to block Union forces north of him; in practice, the Federals in the Shenandoah were inactive, leaving Johnston free to move as he pleased.

By mid-July 1861, after many delays and troubles, McDowell was ready to take his amateurish army into battle. His objectives were necessarily limited: he planned to march south and take Manassas Junction. More ambitious goals would have to wait until the Union army was more experienced. McDowell still had his misgivings over even this simple movement. Not only were the militia units in general poorly trained, but he had little cavalry to provide intelligence and almost no engineers. However, he also had his orders, and the Union army moved out on Tuesday, 16 July 1861.

General Beauregard knew all about the move; Confederate sympathizers in Washington were keeping him well informed. Washington was full of spies and Union security was extremely lax, with important information printed in the newspapers. Joe Johnston had already left the Shenandoah Valley to reinforce Beauregard.

The Federal plan was simple. 30,000 men would march down the Warrentown Turnpike southwest through the towns of Fairfax Courthouse and Centerville. They would then engage Beauregard's forces, which were lined up along the far side of the Bull Run River, north of Manassas Junction, about 30 miles (48 kilometers) from Washington. The march went poorly. The men were not in good condition and were undisciplined; they broke ranks to pick berries, and engaged in scattered acts of looting and vandalism. They reached Centerville on Thursday, and McDowell had to spend two days trying to get them in order for battle. They finally moved out in the dim morning light of Sunday, 21 July 1861.

The Confederate forces were lined up along the length of the Bull Run River in front of the Federals. The Warrentown Turnpike crossed the Bull Run over a stone bridge. McDowell intended to make demonstrations at and to the south of this bridge, while he swung around to the north with 14,000 men, in hopes of fording the Bull Run and then falling on the Confederate flank.

The plan was sound and had a good chance of success, since there were few Confederates in the way of McDowell's flanking movement. However, the long delay in getting down the road from Washington had given Joe Johnston enough time to link up with Beauregard. Most of Johnston's men were still in transit from the Shenandoah; they would arrive by train during the day. Johnston outranked Beauregard and so now technically was the battlefield commander, but Beauregard was familiar with the situation at hand, and in fact was planning to make a counterstroke of his own, with a great flanking move to the south of the enemy line.

The same disorganization that had plagued the march from Washington bogged down the attack as well, and the Union flanking column didn't make it across Bull Run until late in the morning. The diversionary attacks went off more or less on schedule, but they were so faint-hearted that Beauregard and Johnston quickly recognized them as theatrics. In the meantime, the rebels had spotted the Union flanking move. The Confederate commander at the stone bridge, Colonel Nathan G. Evans of South Carolina, swung his forces of about 1,100 men north and advanced until they made contact with the Federals.

In the lead of the Federal column were regiments under General Ambrose Burnside, a militia general from Rhode Island with regular Army background who wore sideburns so enormous that he is said to be the origin of the term. His attack was clumsy and made little progress, but eventually Union artillery began to wear down Evans' men. Both sides called in reinforcements. By late morning, the Federals had broken the Confederate line. The rebels fell back south of the turnpike and re-formed along with more reinforcements on a hill where there sat the house of a farmer named Henry.

Johnston and Beauregard moved up additional troops to meet the threat. Five Virginia regiments that had come with Johnston from the Shenandoah were lined up by their commander, Brigadier General Thomas J. Jackson, to wait for the Federal advance up the hill. By noon, however, the Federals appeared close to breaking through and throwing the rebels off the battlefield. Some Confederate regiments were standing firm, among them General Jackson's Virginians.

Jackson himself was an odd duck, a religious zealot full of warlike Presbyterianism, perfectly fearless in an undemonstrative sort of way, as if it never crossed his mind that he might ever be in any danger. As other rebel regiments crumbled, an officer rode up to Jackson and cried out: "General, they are beating us back!"

Jackson calmly replied: "Sir, we will give them the bayonet." General Barnard Bee of South Carolina, encouraged by Jackson's solid stand, decided to use his example to rally his own wavering men. Bee stood up in his stirrups, and shouted at them: "Look! There is Jackson standing like a stone wall! Rally behind the Virginians!" A bullet then hit Bee in the stomach and knocked him off his horse. Bee would soon die of the wound, but some of his men rallied and fell in with Jackson's Virginians. Confederate resistance began to stiffen.

The fight for the Henry Hill grew in ferocity. The Federals could not coordinate their attacks, and Union artillery batteries found themselves exposed to murderous rebel fire. Some of the firing came from the vicinity of the Henry house. The Federals shot back with their cannon, incidentally killing the invalid mistress of the house, 84-year-old Judith Henry, as she lay in bed.

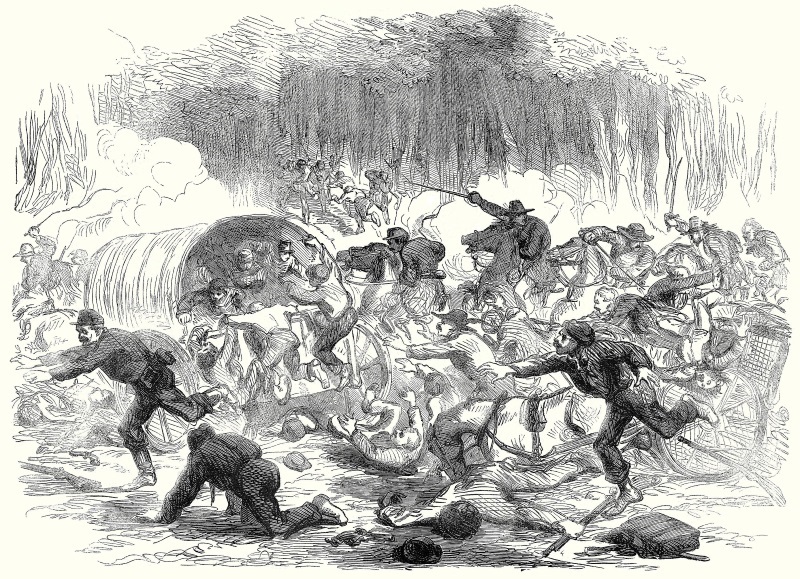

The Fire Zouaves and a battalion of marines were sent forward to support the batteries, only to find themselves facing a wild charge by a Virginia cavalry regiment under the command of General James Ewell Brown ("Jeb") Stuart; the Zouaves broke and ran. Stuart had actually been confused himself, thinking the Zouaves were an Alabama outfit that was facing him because they were getting ready to retreat; "Don't run, boys, we're here!" he shouted -- then realized his mistake and turned it to his advantage, tearing into the surprised Federals. Profiting from the confusion, a Confederate regiment that was wearing blue uniforms managed to march right up to the Union batteries unmolested, then fired into them. A Union officer watching the action through field glasses wrote later that "it seemed as though every man and horse of that battery just laid down and died right off."

By this time, although McDowell had reached the hilltop and was observing the battle from the Henry house, the Union attack was completely falling apart. The Confederates were gaining the initiative, hitting the Federals with counterattacks. Jackson ordered his men: "Hold your fire until they're on you. Then fire and give them the bayonet. And when you charge yell like furies!"

The Union attacks disintegrated, and Yankee soldiers began to fall back off the firing line. There was no great panic at the moment, and McDowell hoped he could rally them back up the turnpike at Centerville. However, the battle had taken place on Sunday, and many proper citizens of the city of Washington, including at least sixteen congressmen, thought that watching a battle would be a pleasant holiday outing. They had taken their carriages and picnic baskets, and even in a few cases their women, down to the slopes of the Bull Run to watch the war in progress. They couldn't actually see much, since the battlefield was covered with smoke and dust, but it soon became obvious that things weren't going well for McDowell's army. The citizens decided it might be wise to move back out of harm's way.

There was a creek named Cub Run a little over a mile up the turnpike from Bull Run. The military and civilian traffic fleeing the battlefield had to cross this stream over a little bridge, and the result of all converging on this chokepoint was a traffic jam. Then panic began to spread, and soldiers began shouting: "Black horse cavalry! Black horse cavalry!" -- in the frightened but mistaken belief that Confederate riders were tearing into the confused mob.

McDowell had reserves in Centerville, about 5,000 men, and a few of the units that had been on the field of battle were still in good order. He deployed them in front of the town in order to halt any Confederate advance, while he reorganized the rest of his army behind it; but there was no rallying the confused mob. McDowell could do nothing but fall back to Washington and hope to hold the line at the Potomac.

The Union had suffered an embarrassing defeat. At 0200 AM that following morning, back in the mountains of western Virginia, General McClellan received a telegram from Washington:

CIRCUMSTANCES MAKE YOUR PRESENCE HERE NECESSARY. CHARGE ROSECRANS OR SOME OTHER GENERAL WITH YOUR PRESENT DEPARTMENT AND COME HITHER WITHOUT DELAY.

High hopes had given way to disaster. Congressmen had taken up the cry of: "On to Richmond!" -- but the only one of them who actually made it there, Alfred Ely of New York, did so as a prisoner.

The Federals' immediate fear for Washington proved baseless. The battle had disorganized the Confederates almost as badly as it had the Federals. Jefferson Davis had been riding up to the front even as the battle was being won. He found a rabble of stragglers falling away from the fight and thought it evidence of a defeat. He tried to rally them: "I am President Davis! Follow me back to the field!" General Jackson was not far away, having a wounded hand attended to. When the doctor relayed that Davis thought things were going badly, Jackson shouted in outrage: "We have whipped them! They ran like sheep! Give me 5,000 fresh men and I will be in Washington City tomorrow!"

The Confederates had in fact won a substantial victory. They had driven the Yankees off the field and captured 28 guns, 37 caissons, plus a huge litter of rifles, pistols, blankets, wagons, and other items. However, both Johnston and Beauregard knew their army was in no shape for any further real fighting. Jefferson Davis was inclined to order them to try anyway, but he thought it over and did not. Davis was later much criticized for this decision; in fact, McDowell still had 10,000 men in good fighting condition, and they would have easily held the bridges into Washington, with the rebels suffering badly if they tried to press the matter. The fighting was over for the moment.

* On 22 July, while a dismal rain fell, the defeated Union soldiers drifted back into Washington. They were dirty, miserable, hungry, and exhausted. They collapsed wherever they could find shelter and slept like the dead. Many officers had drifted into Williard's to seek comfort in alcohol and tell their own sad tales. A writer and poet named Walt Whitman, who had been squeaking out a living in Washington, saw the mob and Williard's and wrote acidly:

QUOTE:

There you are, shoulder-straps! But where are your companies? Where are your men? Incompetents! Never tell of chances of battle, of getting stray'd, and the like. I think this is your work, this retreat, after all. Sneak, blow, put on airs, there in Williard's sumptuous parlors and barrooms, or anywhere -- no explanation will save you. Bull Run is your work; had you been half to one-tenth worth your men, this would never have happened.

END_QUOTE

Whitman had a point. The Federal soldiers had fought well and been badly bloodied, with maybe 500 confirmed dead, more than 1,100 wounded, and over 1,500 missing in action, most of them captured. Many of the wounded would die or be maimed for life. The Confederates had been hurt about as badly, with 400 killed and more than 1,500 wounded, though being the victors they lost only a handful as prisoners. The disorganization that ultimately defeated the Federals was to a large extent a failure of leadership. There was a search for the guilty. McDowell was accused of every failing, even drunkenness, though his hatred of demon liquor was well known.

The defeat was a bitter disappointment in the North. That noisy jack-in-the-box, Horace Greeley, who had trumpeted ON TO RICHMOND! in his headlines, wrote President Lincoln a gloomy letter speaking of "sullen, scorching, black despair" and suggested that peace be made with the rebels at once. British correspondent William Howard Russell had witnessed the untidy flight of the Union troops and dutifully reported it in the pages of the TIMES OF LONDON. The TIMES was the most widely-known British newspaper in the USA, and once his stories made their way across the Atlantic and back again, Russell would be the target of deep resentment -- aggravated by the fact that the editorial policy of the TIMES was resolutely pro-Southern and poisonously anti-Northern. Russell eventually found that nobody would talk to him or give him passes to cover military operations, giving him no alternative but to go back home.

Lincoln was of course discouraged, but not in the least defeatist. He wrote to his wife two days after the defeat: "The fat is all in the fire now and we shall have to crow small until we can retrieve the disgrace somehow. The preparations for the war will be continued with increased vigor by the government."

The War Department gathered up its scattered soldiers as best it could by issuing rations at a few distribution points where the men could be assembled. State governors sent new militia units to Washington in response to desperate appeals, and the government was quickly able to issue statements reassuring the public that matters were under control and further disasters were not imminent. Lincoln had been preparing for a long war, while hoping for a short one. Now undeceived, he wrote up his plans for the future:

QUOTE:

1. Let the plan for making the Blockade effective be pushed forward with all possible dispatch.

2. Let the volunteer forces at Fort Monroe & vicinity -- under Genl. Butler -- be constantly drilled, disciplined, and instructed without more for the present.

3. Let Baltimore be held, as now, with a gentle, but firm, and certain hand.

4. Let the force now [in the Shenandoah Valley] under Patterson, or Banks, be strengthened, and made secure in its position.

5. Let Gen. Fremont push forward his organization, and operations in the West as rapidly as possible, giving rather special attention to Missouri.

6. Let the forces late before Manassas, except the three months' men, be reorganized as rapidly as possible, in their camps here and about Arlington.

7. Let the three months forces, who decline to enter the longer service, be discharged as rapidly as circumstances will permit.

8. Let the new volunteer forces be brought forward as fast as possible, and especially into the camps on the two sides of the river here.

END_QUOTE

An addition to this list read:

QUOTE:

1. Let Manassas Junction (or some point on one or the other of the railroads near it) and Strasburg, be seized, and permanently held, with an open line from Harper's Ferry to Strasburg -- the military men to find a way of doing these.

2. This done, a joint movement from Cairo on Memphis; and from Cincinnati on East Tennessee.

END_QUOTE

The list showed that Lincoln's mind was of necessity running in many directions at once. One thing was very clear: there would be no short and easy war. It was just getting started.

BACK_TO_TOP* This document was derived from a history of the American Civil War that was originally released online in 2003, and updated to 2019. It was a very large document, and I first tried to simply break it into volumes for publication in ebook format; however, that proved unsatisfactory, and I decided to break it into separate focused volumes. This stand-alone document was initially released in 2021.

* Sources:

When I was interested in picky details, I'd scrounge the internet, particularly the Wikipedia, for leads.

* Illustrations credits:

All maps are the work of the author.

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 dec 21 v1.0.1 / 01 aug 23 / Review & polish. v1.0.2 / 01 aug 25 / Review & polish.BACK_TO_TOP