* The American nation was founded in 1789, unifying 13 former British colonies in a Federal whole. The 13 states of course had differences of opinion among them -- first and foremost being, broadly speaking, that Southern states kept slaves, and Northern states did not. The US Constitution attempted to maintain a balance between the two factions, and for decades a national compromise on slavery was maintained. However, tensions rose, and by the year 1860, events were on the edge of an explosion.

* The origins of the American Civil War lay in the institution of slavery. Slavery had long existed in America, with the southern colonies making large use of slaves from the outset, in part because black Africans were more tolerant of diseases prevalent in the southern colonies. When George Washington took the oath as first President of the United States in 1789, the new Constitution included provisions ensuring the continued existence of slavery -- most notably, granting slave states proportional representation in the new government by their free population, plus three-fifths of their chattel slave population, as well as a guarantee that slave-owners would be able to retrieve their runaway slaves from free states.

Slavery was clearly on the way out in the North, being gradually abolished; many of those who disliked slavery believed that there was no reason to rock the boat over it, since slavery appeared to be on the decline. Slaves had been employed in growing tobacco, but tobacco farming drained the soil and was fading in importance. Even some refined Southern men felt that slavery ought to go in good time -- though they were a minority. The Constitution dodged controversy, not even using the terms "slave" and "slavery", only mentioning "persons held to service".

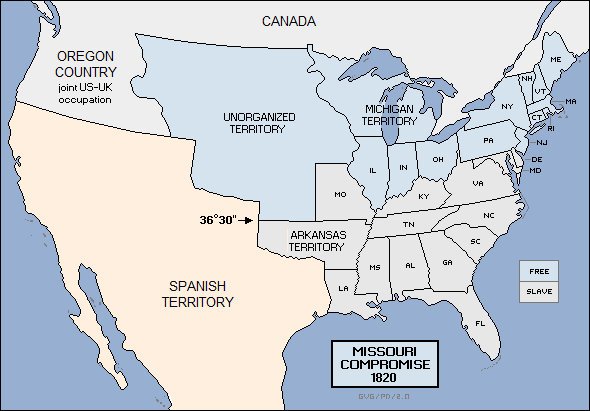

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 specified that slavery would be banned from the vast new Northwest Territory, and in 1807 the North and South agreed to ban the African slave trade. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803, which greatly expanded America to the West, posed the problem of whether the states carved out of the new territory would be slave or free, but a compromise was reached in 1820 in which slavery was restricted to south of the 36:30 parallel; Missouri was admitted as a slave state even though it was above that parallel, as a specific exception. The Missouri Compromise would hold for over two decades. Still, even in 1820 there were those who suspected that matters were taking a turn for the worse, since by that time slavery was on the rebound.

Cotton had long been recognized as a useful source of fiber for textiles, but removing its seeds was troublesome and an obstacle to large-scale production. Then, in 1792, a New England Yankee industrialist named Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin, developing the device in a fit of ingenuity after a visit to the South. The cotton gin was a simple piece of equipment: it used a toothed cylinder to tear cotton lint from cotton bolls through a screen, leaving the seeds behind. Large-scale use of cotton was now practical, and by 1794 production of cotton had grown by an order of magnitude. It would grow at a similar rate over the following decades. Big cotton fields required a lot of labor, and slaves were the cheapest labor around.

Great fortunes could be made in cotton, and slavery began to become much more troublesome. On a small scale, slavery wasn't so outrageous: household slaves, for example, were generally treated as family members and could often be surprisingly loyal to their masters. However, no slave had rights of free movement or expression, and it was illegal to even teach them how to read lest they get dangerous ideas -- though some of the more enlightened slave-owners did it anyway, such laws not always being enforced, since they were so rarely violated. However, there were few niceties to slave life on the big plantations, which were reminiscent of modern forced-labor camps, with obedience maintained by the whip and runaways tracked down by bloodhounds.

The boom in cotton not only led to a revival of slavery, but also led the South down a path of skewed economic development. The South became something like a colony, focused on production of one major raw material, cotton, that was exported to the North and to Britain to be turned into cloth and clothing. The North, in the meantime, focused on the development of manufacturing not only to convert the cotton into salable goods, but to make almost every other conceivable product. Although there was a movement for a time to encourage the industrial development of the South, it accomplished little; while the South stagnated, the North grew in population, wealth, and material power. Since Southern capital was mostly invested in property and slaves, financing ended up being provided by Northerners, increasing Northern power over Southern society.

Southerners grew insecure over their uncomfortable position. They were becoming increasingly dependent on outsiders as a source of revenue, and of manufactured goods that the South could not make for itself. These outsiders, furthermore, had no use for slavery, making them implicitly hostile to the Southern way of life.

* The hostility began to become more and more explicit. In 1829, David Walker, a free black owner of a secondhand clothes store in Boston, Massachusetts, published a pamphlet titled THE APPEAL that encouraged slaves to rise up violently against their masters. The mayor of Savannah demanded that the mayor of Boston ban the pamphlet and arrest Walker; the mayor of Boston refused. In 1831, a white citizen of Boston, William Lloyd Garrison, began publishing an anti-slavery newspaper named THE LIBERATOR. Garrison was something of an eccentric who believed in clairvoyance and spiritualism. He felt a deep sense of moral outrage over slavery, and he was neither tactful nor restrained in his criticisms of slave-owners:

QUOTE:

The Southern planter's career is one of unbridled lust, of filthy amalgamation, of swaggering braggadocio, of haughty domination, of cowardly ruffianism, of boundless dissipation, of matchless insolence, of infinite self-conceit, of unequaled oppression, of more than savage cruelty.

END_QUOTE

THE LIBERATOR never turned a profit and never had more than a few thousand subscribers, but it was a center of agitation. Garrison acquired allies in his struggle, such as his close associate Wendell Phillips -- a die-hard anti-slavery man and a brilliant orator -- and another free black, Frederick Douglass. Douglass had escaped from slavery to become an eloquent anti-slavery man. He wrote an autobiography, which was widely read, and published his own anti-slavery paper, THE NORTH STAR.

While the "abolitionists" could be extreme, they had popular appeal in the Northeast. There was a religious revival at the time, and anti-slavery sentiment was widespread. The breaking-up of slave families was regarded as a particular outrage, with wives separated from husbands and children torn from mothers. Breaking up families was also regarded as cruelty in the South, but if a slave-owner ran into financial difficulty it might be hard to avoid, and it was commonly done when settling estates.

Slavery and slave-owners were bitterly condemned in the North. A nonviolent solution to the problem of slavery might have been a hard sell before, but the insults and abuse heaped on slave-owners, and the calls by abolitionists like Walker for slaves to rise up and by implication butcher the wives and children of the slave-owners, unsurprisingly antagonized slave-owners and made them increasingly inflexible. Discussion became impossible, and moderates found themselves attacked by both sides. In that same year of 1831, a slave named Nat Turner led a small-scale uprising in Virginia, in which 57 whites were killed. The rebellion was suppressed and the renegade slaves killed, but it convinced slave-owners that the abolitionists and their sympathizers were pointing guns at their heads.

Southerners, such as Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, began to assert that slavery was a positive good, a proper relationship between superior and inferior races, and a much more ethical system than enjoyed by workers exploited by Northern capitalists. Some Southerners began to call for the repeal of the ban on the African slave trade, with a few going further and running slaves across the ocean illegally -- and there were even a handful who suggested that the lower white classes be enslaved as well. Attempts were made to suppress the agitations of abolitionists, but such restrictions were ineffective and simply added to the fury.

Garrison was nearly lynched by a mob, and street violence over the matter spread. On 7 November 1837, a mob attacked a warehouse in Alton, Illinois, being used by Reverend Elijah P. Lovejoy, who published an anti-slavery newspaper titled THE OBSERVER. Lovejoy had been driven out of Saint Louis, Missouri, just across the Mississippi from Alton, for his inflammatory editorials, and he and his supporters were not inclined to be driven any further. A gunfight followed, with one of the mob shot and killed. Lovejoy was then shot five times and killed himself. The death of Lovejoy was a shock; now the controversy had become so violent that a white man had been killed over it.

BACK_TO_TOP* In 1844, James K. Polk was elected to the US presidency on a Democratic Party platform pushing territorial expansion. The issue during the election was a dispute over the northern boundary of the Oregon Territory, the slogan being "Fifty-Four-Forty Or Fight", the 54:40 line including what is now British Columbia. A fight actually didn't break out over the matter, with the border established as a continuation of the border at the 49th parallel instead -- but in more than mere compensation, Polk achieved the biggest military conquest in American history by seizing a good chunk of what was then Mexico.

Earlier in the century, the Mexican government had encouraged white settlers to move into thinly-populated Texas. That proved to be a blunder. The settlers had never assimilated -- they were English-speakers who rejected Catholicism and kept slaves, with slavery being otherwise illegal in Mexico -- and never had much respect for Mexican government authority. In 1836, following an uprising, they created the "Lone Star Republic", with Sam Houston as president.

Texas was annexed to the United States as a slave state in 1845. The Lone Star Republic had been involved in persistent border disputes with Mexico, and the US government inherited the border tensions. That was all for the good as far as the Polk administration was concerned. Polk sent an emissary, John Slidell, to Mexico to buy up the New Mexico and California territories to the west of Texas, but in May 1846 the Mexican government turned down the offer.

The US promptly declared war on Mexico. Democrats were all for the fight; members of the opposition Whig Party felt it was pure aggression, but could not stand up to the frenzy -- one Whig congressman saying cynically that he was now in support of "war, pestilence, and famine". American settlers in California rose up under an ambitious US Army captain named John Charles Fremont and set up the "Republic Of California" or "Bear Flag Republic" in June, which was formally annexed by the US in July. Mexican forces counterattacked, the US sent more forces to respond, and the fight for California went into a seesaw that was finally resolved in favor of the Americans in early 1847.

By that time, the Americans had carried the war into Mexico itself. Under two excellent generals, Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott, the US Army thrashed the forces of Mexican dictator Santa Ana, with Scott leading his troops into Mexico City on 14 September 1847. The humiliating Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed in February 1848, with Mexico ceding California and the territories of what would become the US southwest in exchange for $15 million. Polk had wanted to take more land, but realized that excessive greed would create Whig opposition, so he settled for what he could get and paid off the Mexicans to soften the impression that the Americans had simply robbed them.

* Now new territories had been acquired by the United States, leading to the question: would they be slave or free? Polk, although a slaveholder, simply assumed that they would be free, but many politicians from the slaveholding states had other ideas.

The issue had come up during the conflict, with Democratic Congressman David Wilmot of Pennsylvania proposing in August 1846 a rider to a war appropriations bill that specifically stated slavery would not be introduced into the new territories. The "Wilmot Proviso" was motivated both by anti-slavery sentiment and irritation of Northern Democrats over what they saw as Southern domination of their party. Whigs, who weren't happy about the war to begin with -- some believed that it was a deliberate attempt by slaveholders to acquire new slave territories -- fell in behind the Wilmot Proviso. However, at the time there were 15 slave states and 14 free states, and the Wilmot Proviso was rejected in 1847.

That wasn't the end of the matter. Sentiment in the North was overwhelmingly against slavery. Hard-core abolitionists, with their wild and violent talk, were no more than a noisy minority, but most Northerners didn't like the institution -- not always out of moral qualms, but because of the threat of slavery to free labor. Instead of a system where free white folk could work the land in independence, slavery meant plantations run by arrogant aristocrats whose slaves did all the hard work, with free labor rendered irrelevant. Some of these anti-slavery "free-soilers" were unapologetic racists, having no use for black folk even as slaves. Being anti-slavery did not necessarily or even mostly equate to any humane concern for the welfare of black people.

Only the most extreme anti-slavery men wanted to eliminate slavery in the South, since an attempt to do so would be clearly outside the law and would with equal certainty lead to violence, but few Northerners wanted to see new slave states added to the Union. Southerners found that attitude insulting. More substantially, they felt that if slavery were prohibited in the new states, they would be increasingly surrounded and dominated by anti-slavery forces, and the slave states would be increasingly outnumbered in Congress.

The dispute was between North and South, cutting across the traditional party lines of both the Democrats and the Whigs. Since 1848 was a presidential election year, party bosses worked to patch things up and compromises were floated. There were efforts at the time with heavy Southern backing to extend the 36:30 line all the way to the West Coast, but the Northerners rejected the idea. Another proposal was "popular sovereignty", in which a state itself would choose to be slave or free, but the idea obviously cut both ways, allowing either side to win or lose. Since there were substantially more Northerners than Southerners, Northerners were generally more enthusiastic about popular sovereignty.

BACK_TO_TOPThe winner in the 1848 election was Zachary Taylor -- a Whig, but endorsed by Southerners because he was a Southerner himself who owned hundreds of slaves. However, much to their shock, they found out after he took office that he was a slave-owner of the previous era, one who did not like the institution and did not welcome its extension. Once Taylor entered office, he pushed for the admission of California and New Mexico as free states. The result was a quarrel even louder and angrier than that over the Wilmot Proviso. Pro-slavery legislators like Congressman Robert Toombs of Georgia and Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi threatened that Southern states would secede from the Union if New Mexico and California were admitted as free states.

There had been talk of secession before, Thomas Jefferson having argued back in 1798 that state law could override Federal law, and that a state could withdraw from the Union at will. The matter was generally academic then, but there was a serious crisis over the matter in 1832. At that time, the issue was tariffs, not slavery. Tariffs helped keep out foreign competition to American industry, as well as provide the US Federal government with a major portion of its revenue, there being no income tax at the time. Southerners liked low tariffs because they made imported goods cheaper to buy, and since the spine of the Southern economy was cotton, they had no reason to worry about keeping out foreign competition -- nobody was going to import cotton into the South, tariffs or not.

In 1832, the Jackson Administration had put a set of high tariffs into effect. It led to a crisis: South Carolina protested vigorously, passing state legislation to "nullify" Federal law and arming to resist Federal authority. In essence, South Carolina was not merely defying Federal law, it was attempting to override the Federal right to collection of revenues from traffic through the state's ports, which would have been intolerable to less hardened cases than Jackson. He displayed little patience with the action, calling the resistance "treason" -- with justification, the Treason Clause of the Constitution, Article 3 Section 3, defining the term as warlike acts against the US government.

Jackson sent US Navy warships to Charleston, South Carolina as a show of force, in effect daring South Carolina to commit treason. There was a tense and uneasy stand-off; South Carolina was not getting much support from other Southern states, but the state government needed a face-saving compromise to back down. In 1833, Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky managed to push through legislation that would gradually reduce tariffs, and the "Nullification Crisis" passed.

In response to the new threats of secession from "State's Rights" men like Toombs and Davis, their Northern colleagues called the threats a bluff. Zachary Taylor called the Southern bluff, saying that he would resist secession by force, and hang as a traitor anyone who took up arms against the Federal government. There were still some on both sides who wanted to come to an agreement. Henry Clay was a slave-owner, but he felt it was an evil and wanted to see it gradually abolished. Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts was a solid anti-slavery man. Both Clay and Webster were strong Unionists, and they worked for months to hammer out a compromise.

The tug-of-war over the issue went on in full force until the summer of 1850 -- when, on 8 July, Zachary Taylor died from a combination of extremely hot weather and gastric distress. The new president, Millard Fillmore, was something of a mirror image of Taylor: Fillmore was a Northern Whig who was pro-Southern, a "doughface". The balance of power had shifted, and compromise was now more possible.

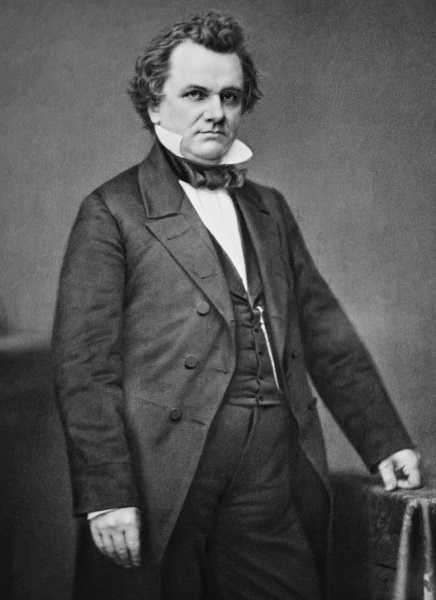

The deadlock was finally broken by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, known as the "Little Giant" for his short height and big ambitions, He managed to push through an agreement: California would be admitted to the Union as a free state, while concessions were made to slave-owners about other acquisitions. The result of the "Compromise of 1850" was a release of tension and celebration: "The Union is saved!" -- was the cry in Congress. The extremists were marginalized for the time being.

The Compromise of 1850 might have calmed tempers, but it had a shadow. The original Constitution had permitted slave-owners to retrieve their "property" from free states; unsurprisingly, the citizens of free states had not always been particularly enthusiastic about assisting slave hunters come North to snatch black folk and drag them South again. Some slave hunters were also not always very fussy about who they seized, nor scrupulous in cooperating with state authorities. As a result, a number of Northern states passed "personal liberty laws" to restrain the slave hunters.

Southern slave-owners were outraged with the personal liberty laws, seeing them as a means by which Northern states stole their "property" and refused to return it, in violation of the Constitution. As a result, the Compromise of 1850 package also included the "Fugitive Slave Law", a Federal statute that backed up efforts to recapture escaped slaves with Federal authority, overriding state laws. The number of black folk seized in Northern states rose sharply, as did the number of black folk running to Canada. The city of Boston, the epicenter of abolitionism, refused to cooperate, resisting Federal authority. President Fillmore was not going to let Boston defy the Federal government: in April 1851, hundreds of soldiers and sailors enforced the return of a teenaged slave named Thomas Sims.

The effects of the Fugitive Slave Law were felt elsewhere, with the tensions leading to violence. On 11 September 1851, US marshals and a group of slave-owners descended on Christiana, a small Pennsylvania Quaker town whose citizens were inclined to hide escaped slaves. The intruders were after two fugitive slaves, who they found -- accompanied by twenty armed black men. Two Quakers suggested that the slave-owners depart for their own safety, but they were obstinate and a shootout followed, with a slave-owner killed and his son seriously wounded. Fillmore literally sent in the Marines, who worked with Federal marshals to make arrests. A Federal grand jury indicted 36 blacks and five whites on charges of treason. The incident became a national news circus; the case against the accused soon fell apart of its own dead weight and was dismissed. Southerners were outraged at the dismissal of the case, feeling that once more Northerners were trampling over their rights.

Finally, controversy over the Fugitive Slave Law began to die down. Head-on defiance against Federal authority having proven unwise, citizens of abolition-minded cities like Boston became quick to spirit escaped slaves off to Canada, instead of trying to stand and fight. Northern factions who were disinclined to rock the boat in the first place began to encourage the citizenry to abide by the law, however disagreeable it might be, for the sake of national unity. Some Northern states where feeling against black folk was strong went even farther in making sure they had no problems with the Fugitive Slave Law: in 1851 Indiana and Iowa passed laws forbidding black people, slave or free, to live inside their borders, with Illinois doing the same in 1853.

That didn't mean that tensions disappeared. In 1852, a New Englander named Harriet Beecher Stowe published UNCLE TOM'S CABIN, OR LIFE AMONG THE LOWLY, a depiction of the brutalities of slave life. It wasn't a great work of art: Stowe had very little first-hand knowledge about slavery, and it was more heavy-handed propaganda than literature. The book still became a best-seller, selling hundreds of thousands of copies. It helped turn public opinion even more against the slaveholders. The reaction to UNCLE TOM'S CABIN in the South was offended, loud, and angry, to the point of becoming a Southern obsession.

BACK_TO_TOP* Franklin Pierce was elected president in 1852 on a Democrat platform of further expansion of the USA, but his actual territorial acquisitions were limited to the purchase of a chunk of land for $15 million at the southern end of what is now New Mexico state in 1854, negotiated by the American ambassador to Mexico, James Gadsen. Anti-slavery Northerners suspected that the "Gadsen purchase" was driven by the Southern desire for new slave lands; the territory acquired was a modest snack towards such an end, but many Southerners had their eye on Cuba as a more substantial meal. A slaveholding US state of Cuba would be a desireable addition to the South.

Polk had tried to buy Cuba from Spain for $100 million in 1848 but the Spaniards wouldn't sell to him, nor to Pierce when he tried in 1853. Several attempts to back invasion forces to seize the island came to nothing. The idea still remained tempting to many Southerners, and in fact there were those who believed that the US should conquer all of Mexico and Central America, turning the Caribbean into an American lake ringed by slave states. An adventurer named William Walker did manage to seize Nicaragua in 1856 and set it up as a slave nation -- only to be chased out by the forces of neighboring nations, and then executed by firing squad a few years later after an attempt at a comeback. Efforts to bring the Spanish-speaking lands to the south into the American fold would go nowhere. The practical focus of slaveholders would be to extend slavery into the new western territories of the USA.

Franklin Pierce was also a doughface, a Northerner strongly sympathetic to the South. His attempts at territorial expansion, though not very effective, did make Southerners happy, as did his insistent enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law. In 1854, a slave named Anthony Burns stowed away on a ship to Boston; Pierce ordered Federal forces to grab the runaway and see to it that he was sent back. The heavy-handedness of the government upset many Northerners, one saying that he and his neighbors had gone to bed one night as conservative Whigs to wake up the next morning as "stark mad Abolitionists."

Agitation over the Fugitive Slave Law remained an irritant, but it wasn't where the real trouble would emerge. Stephen A. Douglas wanted to push through a transcontinental railroad from Chicago to San Francisco, and worked to organize the territories to the west of Missouri and Iowa to permit the railroad to run through the region. However, Southern legislators wanted a transcontinental railroad running from New Orleans through New Mexico to the West Coast, and he had to cook up a deal with them.

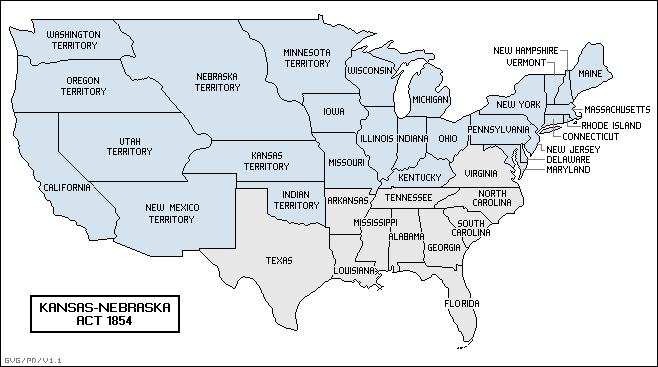

Under pressure, Douglas proposed a bill that set up "Kansas Territory" to the west of Missouri and "Nebraska Territory" to the west of Iowa. Whether these territories would be slave or free would be up to popular sovereignty, the will of the citizens of those territories. The territories were north of the 36:30 line, and anti-slavery forces saw the concept of popular sovereignty as simply a dodge for breaking through the barrier. Douglas and Southern Democrats managed to push the bill through in May 1854 with backing from the Pierce Administration, but the political cost was very high. When Douglas went back to Illinois after passing the act, he was greeted at almost every stop by fiery effigies of himself.

More significantly, the Kansas-Nebraska Act effectively destroyed the Whigs. The Northern and Southern halves of the party had already been split, with Southern Whigs becoming Southern Democrats. Two new parties would emerge from the ruins of the Northern Whigs. The first, the "Know-Nothings", was much along the lines of what would now be called a "Nationalist Party", hostile to foreign immigrants and their ideologies -- in this case, mostly the Irish and Catholicism. The name came from the secretiveness of the movement, with members answering "I know nothing" when queried about their activities.

The Know-Nothings were more of a disorderly mass than a real political organization, and though Know-Nothingism was a force at the moment, as is often the case with incoherent populist movements, it would dissipate in a few years. The second new party, the "Republicans", was built up on a bedrock of free-soiler Whigs and would become a force to be reckoned with, particularly as Northern voters turned against Northern Democrats for their apparent collaboration with attempts by Southerners to spread slavery. By 1856, Republicans had control of the US House of Representatives; the Know-Nothings had all but ceased to exist, their extremism spent and, to an extent co-opted by the Republicans -- who adopted some of the Know-Nothing rhetoric, but did little to further Know-Nothing goals.

* The lightning emergence of the Republicans was due to the extremely untidy way the consequences of the Kansas-Nebraska Act played themselves out. Kansas, next door to slave-state Missouri and with lands well-suited to cultivation by slaves, became the focal point of conflict. To no surprise in hindsight, if it was even a surprise at the time, the concept of popular sovereignty meant a race between pro-slavery and anti-slavery people into Kansas, and warfare between the two factions once they arrived.

Pro-slavery Missourians, who became known as the "border ruffians", moved into Kansas quickly to forestall free-soilers. In the fall of 1854, the new territorial governor of Kansas, a pro-slavery Pennsylvania Democrat named Andrew Reeder, called for elections to send a delegate to Congress. The election was a farce. Although pro-slavery settlers might have won legitimately in a fair election, they still resorted to intimidation, one of their leaders saying that the faithful should mark anyone among them who was "the least tainted by free-soilism or abolitionism and exterminate him."

Reeder was ideologically sympathetic to the pro-slavery faction, but their threats -- including a good number against him personally -- altered his attitude. He ordered new elections in about a third of the districts in Kansas, with free-soilers generally being elected; however, in 1855 the pro-slavery territorial legislature simply refused to seat them. Reeder went to Washington DC to plead for help from President Pierce, but the only result was that Reeder was sacked, to be replaced as territorial governor by Wilson Shannon of Ohio, who strongly backed pro-slavery forces.

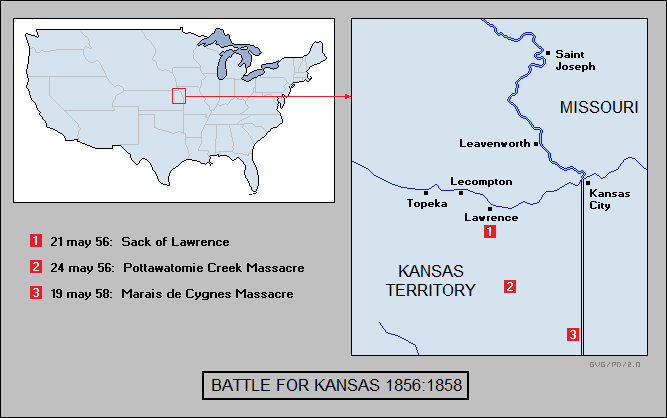

By late 1855, however, the population of Kansas had tilted towards the free-soilers, and they had no intention of submitting to the pro-slavery territorial government. They set up their own territorial government in response, and by early 1856 Kansas had two different governments -- a pro-slavery government in Lecompton, which had the distinction of being recognized by Washington, and a free-soil government in Topeka, which had the distinction of actually representing the majority of the territory's population. Both sides were armed; it was a little civil war, waiting to happen.

* Hostilities between pro-slavery and free-soil forces in Kansas had already started in November 1855, when a free-soiler murdered a pro-slavery man. 1,500 armed Missourians then marched on the free-soil stronghold of Lawrence, where they ended up in a stand-off with a thousand armed free-soilers. The Pierce Administration stood idly by and the US Army didn't intervene. Governor Shannon managed to talk the Missouri men into going home -- though less by appealing to their better nature than suggesting that an attack on Lawrence would give abolition forces a propaganda victory.

That merely postponed violence until the next spring. More free-soilers were pouring into Kansas and the pro-slavery men became nervous. When pro-slavery Judge Samuel Lecompte had a grand jury indict members of the alternate free-soil territorial government for treason, the pro-slavery men felt encouraged to return to Lawrence and finish the job. The free-soiler leadership, realizing they were on tenuous legal ground, decided against fighting back; the pro-slavery men looted and trashed Lawrence on 21 May 1856.

The news of the "Sack of Lawrence" shocked the North; another shock came along with it. Republican Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, outraged at the situation in Kansas, had delivered an extended blast against pro-slavery forces on 19 and 20 May. Sumner was a hard-core anti-slavery man, humorless and inflexible in his hatred of the institution, and willing to speak his mind at length and with no consideration of tact. The speech, titled "The Crime Against Kansas", was angry and intemperate, abusing congressmen from slave states by name, and used extremely blunt, even crude language. The speech was meant to be provocative, and it worked as per design: two days later, on 22 May, Congressman Preston Brooks of South Carolina set on Sumner in the Senate chambers, smashing him over the head repeatedly with a gold-headed cane until the cane shattered. Sumner survived the assault; he went to Britain to recuperate, where he was received with considerable sympathy.

The incident, vicious as it was, might not have been so politically troublesome except for the fact that Brooks end up with nothing more than a fine of $300 from a district court, and was lionized all over the South. Even Northerners who had little sympathy with Sumner and his inflammatory rhetoric were appalled, since the cheers from the South seemed to reinforce the claims of the abolitionists that Southerners were brutes and thugs whose only idea of dealing with a dispute was to bash an opponent over the head.

Back in Kansas an abolitionist zealot named John Brown, already agitated over the Sack of Lawrence, flew into a mad rage when he heard about the assault on Sumner and decided to teach the pro-slavery men a lesson. Figuring that they had murdered about five free-soilers since the troubles in Kansas had begun, he and his men snatched five pro-slavery men, effectively at random, from around his homestead on Pottawatomie Creek on the night of 24:25 May 1856. All five were executed by a blow to the head with a broadsword.

Pro-slavery men burned Brown's home, but he managed to evade capture. The violence in Kansas spiraled out of control. "Bleeding Kansas" made headlines elsewhere, with the stories emphasizing atrocities against pro-slavery men in the South and atrocities against free-soilers in the North.

Northern agitation over slavery was running very high, with anger flaring up over the Fugitive Slave Law. That January, in a particularly notorious incident, a black woman named Margaret Garner who had escaped to Ohio from Kentucky with her husband and four children was cornered by a posse of slave-hunters; rather than see her children returned to slavery, she slit the throat of one of her daughters with a kitchen knife and tried to kill the others before she was restrained. The family was dragged back down to Kentucky, where the owner sold them down the river to New Orleans, with one of the other children drowning after a steamboat collision during the trip.

* 1856 was an election year. The freshly-minted Republicans were pushing John C. Fremont for the presidency, while the Democrats were promoting James Buchanan. Die-hard conservative Whigs, reorganized as the "North American Party", pushed Millard Fillmore for his second term. Fillmore hadn't a chance in the North, Fremont hadn't a chance in the South -- indeed, Southerners were loudly proclaiming their states would secede from the Union if Fremont were elected -- but Buchanan, a colorless government bureaucrat from the North, a doughface with Southern sympathies, had sympathizers in both regions.

Many of these sympathizers were Northerners who heeded the threat that a Republican president would mean secession. Opponents of the Republicans also conducted a smear campaign, saying that the Republicans were out to pull down racial barriers, and that if the Republicans won, the white menfolk wouldn't be able to protect their wives and daughters from black men. The Republicans counterattacked, saying that the Southerners were out to force the institution of slavery on the rest of the country, and held up Bleeding Kansas as an example.

Kansas was still bleeding heavily and Shannon, unable to maintain control over the territory, resigned in August 1856. He was replaced by John W. Geary, a towering and tough anti-slavery Democrat, originally from Pennsylvania, who had brought order to lawless San Francisco when he was mayor there. With 1,300 Federal troops at his disposal and the willingness to use them, by October 1856 the violence in Kansas Territory had finally been brought under control -- for the moment.

Peace in Kansas weakened the Republican cause; it might not have been the fatal blow in itself, but all things considered, Buchanan looked like the better bet to most Americans, and he won the presidency in November. If anyone thought the election of Buchanan settled things down, they soon found they were mistaken, since things quickly began to go to hell in Kansas all over again.

In early 1857, the pro-slavery territorial government of Kansas passed a bill for a constitutional convention, with the bill specifying complete control of the convention process by pro-slavery sheriffs and judges. It was an obvious ploy to declare Kansas a slave state, and Geary vetoed the bill. The legislature pushed it through anyway. Geary -- with no backing from the lame-duck Pierce Administration and confronted with continuous threats against his life -- resigned in early March 1857, firing off a verbal blast at the "felon legislature" in Lecompton as he departed.

When Buchanan entered office, to replace Geary he appointed Robert Walker, a Mississippian of Pennsylvanian origins who had been treasury secretary in the Polk Administration. Walker was an honest man and recognized that pro-slavery men were increasingly a minority in Kansas. He tried to get the free-soil men to participate in the convention, but they wanted nothing to do with it, having been consistently cheated to that time. Of course, pro-slavery men won all the seats to the constitutional convention -- a dubious victory, since only about a quarter of the registered voters participated.

Walker proposed a state referendum on the results of the constitutional convention, with Buchanan backing him up. Since the results were bound to be pro-slavery and the free-soilers were certain to vote them down, Walker's efforts to encourage a more honest political process made him plenty of enemies -- not merely among the pro-slavery men in Kansas, but also among their Southern backers. Jefferson Davis accused Walker of "treachery"; Southerners pressured Buchanan to remove him and cancel the referendum. Buchanan finally gave in to the pressure and did so.

However, before Walker left Kansas he pushed through another election, for a unified territorial legislature, and managed to convince the free-soilers that the exercise was sincere. The result was a landslide victory -- for the pro-slavery faction. Walker was suspicious and investigated, finding for example that one town with 130 registered voters had cast 2,700 ballots. He tossed out obviously bogus returns, and the result was a tilt to free-soilers. Southerners accused Walker of "tampering" with the election.

In the meantime, the pro-slavery constitutional convention had completed its efforts, producing a state constitution that seemed unremarkable -- except for clauses that effectively guaranteed slavery in Kansas. There was to be no referendum, with the constitution simply passed on to the US Congress for approval. Even some Southern Democrats thought that was too baldfaced a trick, and so the Kansas convention modified their position, saying that a referendum would take place after all. The problem was that the referendum only concerned the technical wording of specific pro-slavery clauses in the constitution, and free-soilers quickly recognized that slavery would be guaranteed in Kansas whether the referendum result was YES or NO.

The free-soilers howled about the "Great Swindle", with Walker calling it a "vile fraud". Buchanan remained cowed and backed the referendum, which took place in December 1857. Free-soilers boycotted it, and it confirmed Kansas as a slave state -- with a good percentage of the votes once again turning out to be bogus. The new free-soiler territorial legislature conducted its own referendum in January 1858 on whether the Lecompton constitution should be accepted or rejected. Pro-slavery men boycotted that referendum, which of course rejected the constitution by an overwhelming majority.

With two referendums to choose from, the fury transferred itself for the moment to the US Congress. Southerners of course wanted to accept the Lecompton constitution, with Buchanan heeding Southern threats and endorsing acceptance. Stephen Douglas, who was looking forward to being the Democratic candidate in the presidential race for 1860, now had to make a choice that would doom his aspirations either way: if he accepted the Lecompton constitution, he would lose the North; if he rejected it, he would lose the South. Douglas didn't hesitate, announcing that he would "never force this constitution down the throats of the people of Kansas, in opposition to their wishes and in violation of our pledges." Northerners called him a hero while Southerners damned him as a traitor.

The Senate passed the Lecompton constitution on 23 March 1858, and it went to the House, on one occasion provoking a late-night free-for-all among elderly men who a reporter commented lacked the capability "from want of wind and muscle, of doing each other any serious harm." The intent was there, however, and observers suggested that it had been a good thing that nobody had been carrying any real weapons. The House finally rejected the Lecompton constitution on 1 April 1858.

By this time, Kansas was reverting back to the old customs of violence. On 19 May 1858, pro-slavery Kansans commemorated the Pottawatomie Massacre by snatching 11 free-soilers and putting them in front of a firing squad in a ravine at Marais de Cygnes -- with five killed, five wounded, and one avoiding injury by shamming death. The news spread outrage across the North. John Brown had emerged again, crossing with his band of followers into Missouri to free slaves and attack slaveholders. Kansas free-soil "Jayhawkers" clashed with pro-slavery men. However, the rejection of the Lecompton constitution had tipped the balance finally in favor of the free-soilers, and by the end of 1858 the fighting had finally died out in Kansas. The official body count for the little war there came to 55 dead.

A new state constitutional convention took place in early 1859, with the majority of delegates being Republicans. Most of them had originally been Democrats, but the struggle with pro-slavery forces had radicalized them. To a lesser extent, the struggle for Kansas had done much the same across the North, making the Republicans a power that Southerners saw as a deadly threat to their way of life.

BACK_TO_TOP* Along with the agitation created by the fury in Kansas, anti-slavery forces acquired another reason for anger with pro-slavery forces, when in early 1857, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney (pronounced "tawny") of the Supreme Court handed down a landmark decision on the question of slavery.

A decade before, a slave named Dred Scott from Missouri had sued for his freedom, claiming that since he had lived for a time on military installations in free northern territories, he and his family had become free and retained that status even after moving back to Missouri. He had won his case in a Saint Louis court, only to have the verdict overturned in the Missouri Supreme Court in 1852. He took the case to a Federal court in 1854, which judged against him, and so in 1856 he took the case to the Supreme Court.

Discussion over the case was protracted, but in the end the Supreme Court, then with a Southern majority, rejected Dred Scott's plea, with Taney stating for the court majority that black people were inherently and permanently inferior to whites; that they had no rights as citizens in any state, even though the Constitution had deliberately avoided defining citizenship for whites only; and that since the Constitution had provided guarantees for slavery, Congress had no right to bar it from any state.

This decision, which would go down in history as the worst ever made by the Supreme Court, went much farther than a statement on black inequality: what Taney had said amounted to saying there was no such thing as a free state, that by judicial fiat, slavery was legal in all the American states. It was like abolitionism stood on its head, and anti-slavery forces were outraged. Taney had seen his decision as a weapon to be used against the Republicans, but it backfired. The idea that the Constitution protected slavery even in states that designated themselves free delighted Southern Democrats -- indifferent to the reality that was totally and forever unacceptable to the free states. The Democrats now broke into halves; the Republicans could only end up stronger as a result.

Incidentally, Dred Scott was granted his freedom after losing his suit -- though he died of tuberculosis in 1858, not living to see how thoroughly Taney would be repudiated.

Public tensions continued to grow, and crystallize into one of the classic exercises of American political oratory. In 1858, Stephen Douglas ran for re-election to his Senate seat. He was challenged by an Illinois Republican named Abraham Lincoln, a prominent lawyer who had been a Whig in Congress in the 1840s. Although senators were selected by state legislatures in those days, the two men took their campaign to the public. Both men were brilliant, perceptive, and outstanding orators; Douglas had the edge in sheer volume, since Lincoln had a somewhat shrill voice, but Lincoln had a knack for clever stories and satirical gibes that Douglas couldn't match.

The two men agreed to a series of seven debates in various parts of the state. The debates focused almost exclusively on slavery, with Douglas blasting Lincoln's anti-slavery beliefs, claiming that such views would promote a sectional war and also promoted the loathesome doctrine of "negro equality". Douglas claimed Republicans thought that "the negro ought to be on a social equality with your wives and daughters ..."

Lincoln derided Douglas' claims as sophistry "by which a man can prove a horse chestnut to be a chestnut horse". As far as negro equality went, Lincoln noted that he didn't "understand that because I do not want a negro woman for a slave I must necessarily have her for a wife." He flatly denied that he was in favor of the "social and political equality of the white and black races" but that a black man had the same "natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence, the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness."

In turn, Lincoln pressed Douglas to proclaim a commitment to popular sovereignty, the policy that citizens could exclude slavery from a state if they wanted to, and Douglas didn't hesitate to state that he did, promoting a variation on the idea that was referred to as the "Freeport Doctrine": there was no alternative to popular sovereignty no matter what the Supreme Court said, because slavery could not exist if state and local laws didn't support it. Southerners saw this as another repudiation of their rights, and historians often claim that the Lincoln-Douglas debates cost Douglas his chances for the presidency in 1860 by alienating the South. In fact, Douglas had lost the South when he came out against the Lecompton constitution, and he said little in the debates that he hadn't made clear before.

Lincoln achieved a new prominence through the campaign, but it was a notorious sort of prominence. Early in the electioneering, on 16 June 1858, he had delivered a speech in Springfield, Illinois, his hometown, that made his position perfectly clear:

QUOTE:

"A house divided against itself cannot stand."

I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved -- I do not expect the house to fall -- but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery, will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction; or its advocates will push it forward, till it shall become alike lawful in all the States, old as well as new -- North as well as South.

END_QUOTE

Lincoln went on in this vein to denounce popular sovereignty. He lost the election to the Senate to Douglas, but now he was seen as a leading figure among Republicans. The Republicans made gains elsewhere, emerging as a major force in Congress.

In modern times, there are those who claim that slavery wasn't the real motivation for hostility between North and South, contriving an argument that it was all driven by Northern greed, represented by exploitative anti-Southern Federal tariff policies. The real story is more complicated.

The Nullification Crisis of 1832 had been caused by high tariffs and Southern objections, but since that time the direction of tariffs had been downward. The Walker tariff of 1846, pushed by Polk's Treasury Secretary Robert Walker and backed by Southerners, rationalized the tariff system and set up duties at an average of 20% -- a considerable reduction and a low level for the time, particularly in consideration of the fact that tariffs were the primary source of Federal revenue. In 1857, Southerners pushed for and got an even lower tariff, about 18%. Republicans antagonized Southerners by lobbying for higher tariffs, but Northern Democrats didn't like high tariffs either, and the Southerners and Northern Democrats had every reason to think they could work together to defeat the attempts of Republicans to push high tariffs through Congress. In fact, they defeated them for the next two years.

The tariffs issue was nothing, a molehill, compared to the explosive volcano of agitation, anger, and violence over slavery whose thunder and fury rumbles to this day. Kansas wasn't in flames over tariffs; Lincoln was not making high-profile speeches about them. He had made no secret of his hostility to slavery, and slaveholders correctly saw him as an enemy.

By 1859, events were primed for an explosion, waiting simply for a spark to set them off. That spark was John Brown.

BACK_TO_TOP* John Brown had kept a low profile from 1858 into 1859, moving around quietly to find backers for an ambitious project. He planned to start a slave rebellion in the hill country of Virginia to seed a republic of liberated freemen that would expand as more recruits came over to the cause. He got backing from a half-dozen prominent abolitionists -- all of them white, prominent black freemen not being enthusiastic about the plan. In August 1859 he met with Frederick Douglass to outline the plot, saying that it would begin with the seizure of the Federal armory at Harper's Ferry, Virginia, with the weapons seized there to arm slaves joining the insurgency. He wanted Douglass to provide leadership for the legions that would emerge.

Douglass turned him down flat. With more perceptiveness than many others would show later, Douglass described Harper's Ferry as a "perfect steel trap", hemmed in by the confluence of two rivers and surrounded by high ground. Douglass told Brown that "you will never get out alive".

Brown made little more headway with promoting his scheme for the next few months. He finally decided to just go with what he had, making so few real preparations that it was almost as if he were expecting to fail. On the evening of Sunday, 16 October 1859, Brown led a band of thirteen white and five black men into the town of Harper's Ferry, Virginia, along with a wagon full of guns and pikes. His band occupied the town's Federal armory, arsenal, and engine house, taking hostages in the process.

That was a far as Brown got. The local slaves stayed quiet, while the townspeople surrounded the armory and began taking Brown's men down. On Tuesday morning, a band of United States Marines arrived under the command of two Virginian US Army officers, Colonel Robert E. Lee and Lieutenant J.E.B. Stuart. The Marines quickly overcame the insurgents -- with ten of Brown's men killed, including two of his sons. Brown himself was slashed with a sword and seriously injured. Most of his backers fled to Canada; some would be investigated later, but by that time events would make their activities of little interest, and the investigations did not lead to any arrests.

John Brown's raid had been a complete failure relative to its goals, but in a backwards way it would prove a success. Brown had always been an unbalanced and violent man, but in the courtroom he discovered a spiritual transcendence, a dignity he had not had before. Henry David Thoreau wrote: "He is not old Brown any longer; he is an angel of light." The only card he had left was martyrdom, and he played it to the hilt. Brown was executed in Charleston, Virginia, on 2 December 1859. He was 59 years old. He went to the gallows quietly and calmly. His conduct in his trial and execution won widespread admiration all through the North, though most were careful to describe his action at Harper's Ferry as the act of a madman.

Such distinctions were lost on Southerners; they were as outraged, more outraged, over the praise given to Brown by Northerners as Northerners had been over the Southern applause for Brooks' assault on Sumner. Southerners were as angry as modern Americans would be at expressions of admiration for an international terrorist who had been caught trying to bomb a kindergarten. Brown's raid fully radicalized the South, with Northerners in the region treated with suspicion when they weren't run out of town or even assaulted. Rumors ran wild of other conspiracies of Yankees to provoke slave uprisings, with some of the stories printed in the papers. Moderate Southerners tried to speak out, one saying that the stories inevitably turned out on examination "to be totally false, and all of them grossly exaggerated" -- but the rumors went on.

Many Southerners began to seriously consider secession, some claiming they had a right to do so. Although no clause in the Constitution discussed secession, the logic went that since the states had voluntarily joined together, they could voluntarily go their own way. That was absurd: in establishing the Union, the states had set up a Federal government superior to the states, not a confederation of states. America had tried a confederation for about a decade and found it wanting. The framers of the Constitution realized that, without a central government superior to the states, the states would descend into rivalries, even wars, with foreign powers entering into the fray. The Constitution was established on the basis that the states joining into the Union had given up their sovereignty.

To claim that the fact that the Constitution did not prohibit secession implied a right to it was ridiculous; that was like saying a contract with no escape clause could be unilaterally repudiated without consequences. Under the terms of the act of union, it was a preposterous notion that a state government could authorize its citizens to ignore the directives of the national government, any more than a municipal government could authorize its citizens to ignore state law.

It was particularly outrageous for a state government to interfere with the right of the Federal government to obtain the revenues from duties and suchlike, as South Carolina had proposed to do in 1832. That implied the use of force to obstruct the actions of the Federal government, which would be treason. All attempts to challenge or nullify Federal authority in any specific way in previous decades had been rejected by Federal courts. What was secession but comprehensive nullification?

To be sure, if states didn't have the right to defy Federal authority, the states did have a right to challenge it. However, any such legal challenge would be dealt with in Federal court -- after all, it didn't matter if states thought they had a right to secede, it only mattered if the Federal government was legally obligated to agree. The burden of proof was on the South to demonstrate the legality of secession, which Southerners recognized might be hard to do. Although the Taney Court was clearly sympathetic to the South, it wasn't a good bet that the Federal judiciary would agree to simply discard its authority over the states.

To make a court case even more difficult for the states, the question of the legality of secession was obviously linked to the question of justification for doing so -- and the states would be hard-pressed to identify specific actions of the Federal government that honestly provided any such justification. Even if the states had claimed such specifics, the courts would have either rejected or accepted those claims; if accepted, the government would have been required to make correction. In neither case would the court have recognized that secession was justified, even if it were judged legal. If an appeal to the judiciary failed, of course the Constitution could be amended to explicitly permit secession, but that would effectively make secession dependent on a consensus obtained from the states. Given the temper of the times, that didn't seem likely to happen, either.

Secession, in short, was indefensible on a legal basis. There was also the weakness in the practical logic of secession. If the South was motivated to secede by what amounted to the hostility of the North to slavery and not specific policies of the Federal government, secession was certainly not going to change that state of hostility. In fact, secession would tear up constraints on the expression of that hostility -- the legal case for secession being particularly undermined by the reality that secession meant rejection of Federal law and protections.

Many Southerners were skeptical of secession as well, Robert E. Lee writing in a letter some time later: "The framers of our Constitution [would have] never exhausted so much labor, wisdom, and forbearance in its formation if it was intended to be broken up by every member of the [nation] at will." He concluded: "It is idle to talk of secession."

However, Lee was a minority among Southerners of influence. Many of those pushing for secession regarded the argument over the legality of secession as foolish. If the Federal government didn't approve of secession, so what? After all, Britain hadn't accepted the legality of the Declaration of Independence -- but that hadn't stopped American Patriots from rebelling against Britain and establishing the United States. Southerners had no more need to convince the North of the legitimacy of their rebellion than the Patriots had needed to convince the British.

BACK_TO_TOP