* The fighting at Chickamauga Creek began in earnest on Saturday, 19 September 1863, with Rosecrans' Union troops and Bragg's Confederates fighting it out in the woods and rough terrain. In the end, the Federal assault was broken, with Rosecrans forced to withdraw -- though disaster was avoided because of the resolute rearguard action of Henry Thomas and his men. Both sides were badly chewed up; Bragg was not able to organize an effective pursuit.

Rosecrans' men ended up in Chattanooga in a difficult position, isolated and partly surrounded by Confederates on the high ground. Ulysses Grant, the senior Union general in the region, worked energetically to relieve the defenders of Chattanooga, with Rosecrans eventually relieved of command.

* The name of Chickamauga Creek is derived from a Cherokee word and is variously translated as "Dead Water", "River of Death", or "River of Blood". In mid-September 1863, the last meaning, correct or not, would take on an added significance as two large armies massed along its banks.

Moving armies was time-consuming in the days when the only rapid transportation was the railroad. Bragg didn't feel ready to attack until 18 September, when Longstreet's advance units arrived, though Longstreet himself wouldn't get there himself until the next day. Oddly, some of the reinforcements from the east were wearing blue uniforms. The proper ladies of Richmond had sewn them for the soldiers and passed them out while the troops passed through, and though by this time every rebel soldier realized that wearing blue uniforms was a good way to end up being shot at by his comrades, few were in a position to pass up new clothes in the face of coming cold weather. Besides, no Southern gentleman worthy of the name would have snubbed a gift from the womenfolk.

Rosecrans used the delay to get his own men together as fast as possible. By the time the shooting started in earnest on the morning of 19 September 1863, each side had about 65,000 effectives, though some of Rosecrans' troops were still on the march towards the battlefield.

* The area around Chickamauga Creek was a nasty place for a battle, a heavily wooded valley in mountainous terrain. There were not many places where it was possible to see much more than a good stone's throw in any direction, which meant that combat would be confused and difficult to manage.

The southern end of the Chickamauga battlefield was defined by Lee & Gordon's Mill, on Chickamauga Creek itself where it was bridged by the Lafayette-Rossville road. The road ran almost straight north on the west side of the stream for several miles and then forked, with the left fork going to the town of Rossville and then to Chattanooga. There were hills to the west of the road. Chickamauga Creek ran roughly parallel to the road, meandering to the north-northwest. Bragg hoped to flank Rosecrans' army from the northwest, which would cut the Federals off from Chattanooga and their only realistic line of supply or escape. Once the Yankees were isolated, Bragg planned to force them south into the cul-de-sac of McLemore's Cove and destroy them.

On the afternoon of 18 September, Bragg's troops began to cross Chickamauga Creek at various points, with the movement continuing all night. However, Rosecrans had anticipated that Bragg would try to flank the Army of the Cumberland from the north, and so the Federal positions had been moved north as well. Instead of facing the flank of the Federal army, the rebels were confronted by Thomas and his divisions; in fact, after sunrise on the 19th, it was Thomas who began the fight. He sent forward a division under Brigadier General J.M. Brannan, believing incorrectly that they faced a single rebel brigade that had been incautiously left exposed and vulnerable.

In reality, Bedford Forrest and his troopers were in the path of the Federal attack, having gone across Reed's bridge, a few miles up the stream from Lee & Gordon's Mill, to scout out Bragg's planned flanking movement. The rebel cavalry held up the Federal advance while the Confederates moved up reinforcements, who finally drove the Yankees back. Rosecrans shifted a division each from the corps of Crittenden and McCook and hit the rebels again, hard.

The battle began to spiral completely out of control, and it would remain out of control to the finish. A rebel soldier from Alabama described the action as "one solid, unbroken wave of awe-inspiring sound ... as if all the fires of earth and hell had been turned loose in one mighty effort to destroy each other." There was not the least finesse in the fighting; whichever side threw in the most reinforcements would prevail. Casualties were appalling. One of Forrest's officers wrote later: "The ghastly, mangled dead and horribly wounded strewed the earth for over half a mile up and down the river banks. The dead were piled on each other in ricks, like cordwood, to make passage for advancing columns."

Rosecrans came up the line to the fighting in the early afternoon, setting up headquarters in the tiny house of Eliza Glenn, the widow of a Confederate soldier. The Widow Glenn's house was behind the center of the Union line and on a low hill, giving Rosecrans about the best viewpoint possible in the wooded terrain. Since Thomas was at least holding his own or maybe better, Rosecrans was in good spirits and confident. While Thomas' corps held the line on the north, McCook's corps was thrown into the battle to defend the center, and Crittenden's corps was pulled up from Lee & Gordon's Mill to nail down the southern end.

* Thomas' men bore the brunt of the fighting all through the morning and into the early afternoon. However, at about 2:30 PM a rebel division from Buckner's corps under Major General Alexander P. Stewart threw itself at Crittenden's force, in the center of the Federal line. The Confederates hit a division under Brigadier General Horatio Van Cleve, and the Federals, who had just arrived and were in a winded and disorganized state, broke and ran when the screaming rebels erupted from the woods. Van Cleve and Crittenden tried to rally their men but it was hopeless, and the rebels drove toward the Widow Glenn's house -- to then run into trouble.

Two of Thomas' scattered divisions had just marched up to the battlefield and were thrown into the fight immediately. Thomas sent another division from his own lines to help. Now Stewart's men, confronted with three aggressive Federal divisions, found their advance turned into a retreat -- though they gave ground stubbornly, finally pulling out of Union lines to the east and then holding firm.

At that point, at about 4:00 PM, Texan Major General John Bell Hood personally led his division, part of Longstreet's corps, into battle to the south of Stewart's spent troops. Hood had been injured by an artillery shell during the Battle of Gettysburg, losing use of his left arm, and he had been in a Richmond hospital when the move West began. He had no orders to advance against the Federals, but he had tired of waiting and decided to go forward on his own. One of the members of Hood's own Texas brigade, advancing past a badly-bloodied group of Stewart's soldiers, lived up to his ethnic stereotype by calling out to them: "Rise up, Tennesseans, and see the Texans go in!"

Hood's men charged McCook's line, with six Confederate brigades hitting the three brigades of a Union division under General Joseph Davis. The Federals tried to hold their ground but they were totally outmatched, and they crumbled. However, when the rebels tried to follow up their breakthrough, they ran into two more Federal divisions, the very last to arrive, that had also been marching in from the south and luckily happened to be on hand.

In addition, Rosecrans threw in Colonel John T. Wilder's Lightning Brigade. Rosecrans was using the Lightning Brigade as a mounted reserve, and as before their repeater Spencer carbines gave them a hitting power disproportionate to their numbers. Hood, like Stewart, was forced to pull back grudgingly. As the Texas brigade came back, one of the Tennesseans called out to them: "Rise up, Tennesseans, and see the Texans come out!"

As the sun went down, the focus of the rebel attacks shifted back to the north end of the Federal line, with Pat Cleburne throwing his division at the Yankees in an attempt to penetrate their flank. Thomas had been expecting such an assault, but Cleburne's men had been thoroughly trained to fire accurately and load quickly, and the Union line was pushed back about a mile before darkness put an end to the battle for the night. The fighting in the twilight had been furious, with one Indiana soldier saying it was "a display of fireworks that one does not like to see more than once in a lifetime." Cleburne's men caught some sleep in line of battle so that the fight could be resumed when daylight returned. In the meantime, the Federals cut down trees to build breastworks to make sure the rebels got a proper welcome in the morning.

The day's battle had been bloody, confused, and very energetic; by nightfall, there were thousands of dead and wounded littering the ground. There was little water, the night was unseasonably cold, and few of the troops had blankets. Scattershot firing went on all night. Most of the soldiers preferred the shooting to listening to the wounded, lying between the ragged fighting lines. One Union soldier described it simply: "The cries and groans from these poor fellows is perfectly awful." Some of Cleburne's men grew so pained at the moaning of a wounded Union officer that they went into no-man's land, picked the Yankee up in a blanket, and took him behind a small house, where in violation of orders they made a small fire to keep him warm.

* Rosecrans had been very worried at times during the day, since the wooded terrain made it hard for him to know what was happening. He was reduced to listening for the sounds of battle, asking Eliza Glenn where the sound came from, and then trying to locate the fighting on his inaccurate maps. A reporter called the procedure "ridiculous", and the silliness finally came to an end when the proximity of fighting forced Rosecrans to send the Widow Glenn to the rear for her safety.

Given the terrain and the chaotic nature of the fighting, there really wasn't much more that Rosecrans could do. Reporter Charles Dana, who served as an informal agent for War Secretary Stanton, had been sending reports on the battle to Washington by telegraph all afternoon, alternating between optimism and doubt as the battle shifted back and forth.

Nobody really knew what was going on. Rosecrans, always exciteable, was near his wit's end. When a rebel prisoner, one of Hood's men, was taken to Rosecrans to show that Longstreet's reinforcements had in fact arrived, Rosecrans went into a hysterical rage, screaming at the prisoner that he was lying, scaring the young man speechless. The prisoner was taken away. Rosecrans calmed down and admitted that he judged the rebel was telling the truth.

Back in Washington, the War Department was blasting out telegrams to generals all over the West to send whatever troops they could spare to back up Rosecrans. However, there was no way any serious reinforcements could arrive before the battle was concluded one way or another, and Rosecrans knew it. During the night, Rosecrans called a council of war with his generals in the Widow Glenn's house. Phil Sheridan later said of the meeting: "It struck me that much depression prevailed. We were in a bad strait unquestionably."

Thomas was exhausted and kept dozing off, but roused himself every now and then to suggest: "I would strengthen the left." The rebels had focused attacks on Thomas' section of the line in hopes of cutting off the Federal line of retreat, and he figured they would probably renew their attack there in the morning. Since all the serious reinforcements available had already arrived, there wasn't much more that Rosecrans could do to strengthen the left. He was unable to come to much of a decision, though he did suggest that McCook and Crittenden pull in their lines so they might be in a position to help Thomas, if it came to that.

* Longstreet had arrived at the train station that afternoon at about 2:00 PM, only to find that nobody had been sent to greet him. He had to wait about two hours for his staff and horses to arrive, and then went to find Bragg, who was about 20 miles (32 kilometers) away.

The party didn't know the area and night was falling. All they could do was ride towards the sounds of battle, and nearly blundered into Union lines in the process. They didn't find Bragg until about 11:00 PM. Neither Longstreet nor his staff were very happy with their introduction to how things were done in the Army of the Tennessee but Longstreet, a level-headed man, swallowed his annoyance. Bragg had gone to bed, but he got up and spoke with Longstreet for about an hour concerning the plan of battle for the next day.

BACK_TO_TOP* Bragg was reorganizing his own forces for a renewal of the assault in the morning. He divided his army into two wings, with Polk to lead the northern wing and Longstreet to lead the southern wing. Although Polk was supposed to move out just after sunrise, unsurprisingly the attack did not get underway until mid-morning, giving Thomas more time to brace his defense. The delay sent Bragg into a towering rage, cursing Polk, Hill, and all his other generals. Bragg roared at Polk to get moving.

When Polk's men finally hit, they hit hard. Two brigades under Confederate General John C. Breckinridge managed to get on the Lafayette-Rossville road and strike south into Thomas' rear. The Federals managed to crush this attack, all but destroying the rebel incursion, though at fearful cost to themselves.

The rebels were not intimidated in the least and continued their assault, building up pressure in sequence from the north to the south end of Thomas' line, until at about 11:00 all five divisions under Polk's command were committed. The fighting was furious, with many casualties on both sides. Among the more prominent Confederate dead was Brigadier General Ben Hardin Helm, one of First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln's brothers-in-law. His wife would go to live with the Lincolns, who granted her amnesty and took her in.

Under pressure, Thomas had to request reinforcements from Rosecrans. By that time, Rosecrans had completely lost track of things; in an attempt to shore up what he thought was a weak section of his defense, he pulled the division of Major General Thomas J. Wood out of the fighting line of Crittenden's corps and sent it north to help Thomas. The gap in the Federal defense that Rosecrans was worried about didn't really exist, and if Wood's division was moved out of place a gap would be created instead. Wood knew this, but during a mixup earlier in the day, he had failed to move his troops where Rosecrans had wanted them. Rosecrans had given Wood an enraged public chewing-out; Wood was not inclined to question orders again, and he did what he was told. The result was that the Union Army of the Cumberland was extremely vulnerable.

Other Union forces were moving up to close the gap, but they weren't quick enough. At about 11:15 AM, Longstreet hit the southern half of the Federal defense hard with four of his six brigades. Troops of one of the rebel divisions, under Brigadier General Bushrod Johnson, found themselves fired upon from north and south but not from dead ahead. Johnson moved forward quickly and fell on the tail end of Thomas Wood's division, badly chewing it up. By noon, Bushrod Johnson's rebels had penetrated the center of the Union line to a depth of about a mile. He halted and sent back a courier to ask Longstreet for immediate reinforcements.

Directly to the south of Bushrod Johnson's thrust, another rebel division under Hindman had hit McCook's defenses while the defenders, two Federal divisions under Sheridan and Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis, were shifting north to fill in the gap left by the withdrawal of Wood. The Yankees were caught off balance and thrown into great confusion. Hindman moved forward, checked only momentarily when Wilder's Lighting Brigade attacked his flank, blunting the spearhead of the rebel assault until reinforcements moved up and drove the Federal horsemen off. Hindman also halted about noon, maintaining artillery fire on the fleeing Yankees but otherwise waiting for support and new instructions.

To the north of Bushrod Johnson's penetration the other two rebel divisions, under Brigadier Generals Evander Law and Joseph Kershaw, were also enjoying success, though at a stiffer price. Union Brigadier General J.M. Brannan's division had been left unsupported on its southern flank by the withdrawal of Wood's division and the rebels quickly sent Brannan's men swinging back to the northwest. The Federals were able to rally eventually and form up a new line to defend Thomas and his corps. They were assisted in this by 25-year-old Colonel Charles G. Harker, one of Wood's brigade commanders, who on hearing the fighting turned his men around from their column of march and sent them forward in a determined counterattack. They halted the Confederate drive and sent the Texas Brigade rolling back.

Hood, now elevated to a corps commander since Longstreet was the wing commander, tried to rally the Texans, but took a smashing blow in the upper leg from a Minie ball. He had his leg amputated just below the hip on the field. Many assumed he would die, but Hood was made of very tough stuff and survived. Kershaw brought up reinforcements and stemmed the retreat. This was also at about noon. The entire rebel drive had paused to catch its breath and figure out what to do next.

Longstreet moved up to take stock of the situation and prepare the next move, as well as eat lunch. He had good reason to be pleased with matters. Crittenden & McCook's corps had been shattered and sent fleeing through the hills and woods, with the survivors trickling back towards Chattanooga. Both corps commanders were part of the rout, as was Rosecrans. Charles Dana had been taking a badly needed nap in the grass when the rebel attack began, and had been awakened "by the most infernal noise I ever heard" to see Rosecrans crossing himself, which led Dana to conclude that they were "in a desperate situation."

Routed Yankee troops flooded around them. Rosecrans told Dana: "If you care to live any longer, get away from here." Neither Dana nor anybody else in the area needed much encouragement. Dana later remarked: "The headquarters around me simply disappeared." Rosecrans would be accused of cowardice later, but that was unjust, since as far as anybody on the spot could see the entire Union defense had crumbled, and even Phil Sheridan, a tough fighter, was on the run. The road north off the battlefield was blocked by fighting, and the Federals funneled through a narrow pass in Missionary Ridge named MacFarland's Gap, to the rear of Thomas' lines.

A reporter from the Cincinnati GAZETTE gave a verbose description of the scene: "Men, animals, vehicles, became a mass of struggling, cursing, shouting, frightened life. Everything and everybody seemed to dash headlong for the narrow gap, and men, horses, mules, ambulances, baggage wagons, ammunition wagons, artillery carriages and caissons were rolled and tumbled together in a confused, inextricable, and finally motionless mass, completely blocking the mouth of the gap."

However, Thomas was still holding his ground, though his lines had been squeezed into a horseshoe. Some of the Union troops from the shattered southern end of the Federal line who still had fight in them had taken refuge with Thomas and his men, and in fact there were some officers who had lost their commands and were grimly fighting on as infantry in the firing line.

Observing the Union defense, Longstreet recognized that if he could redirect his wing to drive north into the horseshoe while Polk's wing drove south, he stood a good chance of completely crushing Thomas. Longstreet was called to a battlefield conference with Braxton Bragg, explained the situation to Bragg, and concluded with recommendations. Bragg, instead of being excited at the prospect of a victory, seemed annoyed instead. Bragg's original plan had been to drive the Federals south into McClemore Cove, and he simply could not adjust his thinking quickly to such a complete change of plans. However, Bragg's attitude seemed more indifferent than antagonistic and when the conference broke up, Longstreet, typically imperturbable, essentially shrugged, returned to his lines, and prepared for the attack as he had proposed it to Bragg.

* After Rosecrans had fled a few miles from the battlefield, he heard the continued sounds of fighting from Thomas' lines and resolved to return to the fight to help Thomas' men withdraw. Rosecrans spoke to his chief of staff, Brigadier General Garfield, and gave him a stream of orders to instruct him to set up a new line outside of Chattanooga, collect the scattered troops, and prepare a new defense to block Confederate pursuit.

Garfield was bewildered at having so much responsibility dumped on him at once, and suggested that they should switch roles: he, Garfield, should go check on Thomas while Rosecrans attended to setting up a defense around Chattanooga. Rosecrans reluctantly agreed, and Garfield went down the road towards the field of battle. Rosecrans reached Chattanooga later that afternoon. By that time exhaustion and the shock of defeat had set in, and he had to be helped off his horse.

Longstreet renewed his attack at about 2:00 PM. Many Confederates thought they were on the verge of complete victory, that one quick blow would shatter the Federal defense for good -- but they thought wrong. Thomas' men held stubbornly and drove back repeated rebel charges. Hindman, who took a minor wound in the throat but kept on fighting, reported to Longstreet that he had "never known Federal troops to fight so well." Longstreet continued his attacks and Polk, hearing the fighting to the south, ordered his division commanders to renew their efforts.

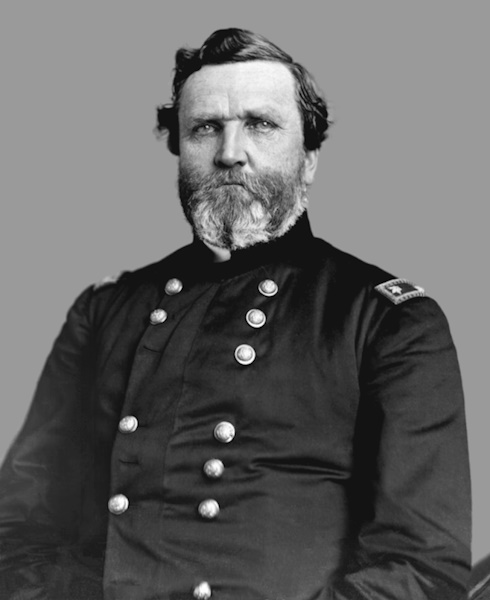

Thomas was soon reinforced by a Federal reserve division under Major General Gordon Granger. Granger was a crusty regular Army officer who wasn't much liked by his men, being short-tempered, a severe disciplinarian, and abrupt with his officers. In compensation he was a fighter, and when he had seen the routed troops flowing past him back toward Chattanooga while hell was popping around Thomas, Granger had taken it on himself to help: "I am going to Thomas, orders or no orders!" He arrived just when Thomas needed him.

Thomas was glad to see him, all the more relieved because he had thought at first that Granger's column was a mass of rebels advancing into his rear. As the Confederates came forward for another assault, Thomas asked Granger: "Those men must be driven back. Can you do it?" Granger replied: "Yes. My men are fresh, and they're just the fellows for that work. They're raw troops and they don't know any better than to charge up there."

Two of his three brigades were ordered in immediately, with the commander of one, a Colonel Steedman, only pausing to ask that his name be spelled correctly in his obituary. Steedman was a courageous fellow, and on seeing his men falter he rode ahead and grabbed the colors: "Go back, boys, go back, but the flag can't go with you!" They rallied and went forward. Steedman survived the fight, but that was not true of many of his men: 3,700 soldiers went in, but by the time the shooting fizzled out in the dark, 1,788 were casualties.

Granger's men also brought along a battery of three-inch (7.62-centimeter) rifles and large quantities of desperately-needed ammunition. Though the rebels tried very hard, they still couldn't crack Thomas' line. However, Thomas couldn't hold out indefinitely. About a third of both armies had or would become casualties, and a third of the Federal force had been driven off the field. That meant Thomas was outnumbered two to one, by Confederates who were pressing him on two sides.

Garfield arrived about 4:00 PM. He had been accompanied by two orderlies, both of them having been killed, and a captain, who had been wounded. Garfield's horse had been hit and collapsed on arrival. Garfield passed on Rosecrans' orders for Thomas to withdraw. Thomas knew he had to pull out, but he wanted to wait until dark when he could withdraw in good order without the Confederates snapping at him. Unfortunately, the pressure was just too great, ammunition was starting to run low, and he finally decided to begin the withdrawal while it was still daylight, hoping the rebels would not be able to press him before night fell.

Thomas's men began pulling out at about 5:30 PM. It was cleanly done under impossible circumstances, with the Federals performing stubborn holding actions when needed, and the survivors bringing up the rear when darkness finally put an end to the shooting at about 7:30 PM. Thomas had been pressed to the limit. Longstreet had committed every man he had, estimating later that he had sent 25 separate assaults against Thomas' men. The Federals had held their ground at the worst the Confederates could throw at them, then conducted a retreat that was incredibly orderly given the circumstances, Longstreet later writing: "Like magic, the Union army had melted away in our presence." From that time on, Thomas was known as the "Rock of Chickamauga".

Northern newspapers did get another source of inspiration out of the defeat, in the form of Johnny Clem. At age nine, he had run away from his home in Ohio to sign up as a drummer boy; he was too little and nobody would take him, but he simply tagged along with the 22nd Michigan Volunteers, conducting himself just as though he had been a real drummer boy. The officers chipped in money to give him a drummer boy's pay. He was at Shiloh, where his drum was smashed by a cannonball, and acquired some public notoriety as "Johnny Shiloh", the "littlest drummer boy".

By the time of Chickamauga, the Army had caved in and formally enlisted him. According to the story, he was riding an artillery caisson during one of the withdrawals of the battle, carrying a rifle that had been modified to fit him, when a Confederate officer ran up and shouted at him: "Surrender, you damned little Yankee!" Clem replied by shooting the officer dead. The newspapers played him up as the "Drummer Boy of Chickamauga".

* There were few other consolations in the battle for the Federals; they'd been whipped and there was no arguing it, while every rebel knew they'd beaten the Yankees and driven them off the field. Confederate troops whooped and yelled wildly. Lieutenant Ambrose Bierce, part of the Union retreat, wrote later: "It was the ugliest sound a mortal ever heard, even a mortal exhausted and unnerved by two days of hard fighting, without sleep, without rest, without food, and without hope. There was, however, a space somewhere at the back of us across which that horrible yell did not prolong itself -- and through that we finally retired in profound silence and dejection, unmolested."

Bragg's excited troops picked up a great haul of loot from the battlefield. Still, many of Bragg's lieutenants knew that they hadn't done enough. They'd hurt the Yankees, but the Yankees had hurt them even more badly in return, and if the Federals managed to get to safety and catch their breath, the rebels would just have to fight them all over again. Longstreet halted his men in the dark to get them reorganized, resupplied, and readied for pursuit in the morning.

It didn't happen. Bragg didn't seem to be aware that he had won, he was undecided when the sun came up the next morning. A rebel private who had been taken prisoner by the Yankees and had escaped during the Federal rout reported to Bragg the extent of the chaos and confusion in the Union ranks, but Bragg was unimpressed. He snapped at the private: "Do you know what a retreat looks like?!" The private was simply annoyed and snapped back: "I ought to, General. I've been with you the whole campaign."

Bragg certainly did not find that funny, but nobody else in the Confederate Army of the Tennessee was in any laughing mood either. Rebel and Yankee dead and wounded simply carpeted the battlefield. There had been about 18,000 rebel and 16,000 Yankee casualties, worse than Shiloh, making Chickamauga Creek the bloodiest battle to take place in the Western theater, then or later. Bragg had shot his bolt and had nothing left; not only had his divisions been terribly torn up, he lacked wagons, all the bridges in front of him had been burned, he had no pontoon bridges, and in particular his horses had suffered as badly or worse on the battlefield as the men. When pressed to move in for the kill on Rosecrans' defeated army, Bragg replied, not unreasonably: "How can I? Here is two-fifths of my army left on the field, and my artillery was without horses."

Bedford Forrest did not agree with that assessment. Bragg's perception of his army's injuries was realistic, but Forrest and his men had scouted out the Federal retreat that morning. Forrest had gone up an abandoned Federal observation post built in a tall tree on top of Missionary Ridge. From that vantage point, he could see the entire defeated Union Army of the Cumberland stumbling back into Chattanooga. If the rebels hit quickly, they would find the Federals an easy target.

Forrest sent a message to Polk, suggesting immediate pursuit before the Federals could organize a defense. Nothing happened. Forrest was "beside himself" with excitement and anxiety as the beaten Yankees managed to get away to safety. Forrest went to Bragg personally and pressed him for a pursuit. Bragg turned him down, saying the army didn't have the ability to move far from the railhead and its source of supply. Forrest was exasperated, since he knew that if they moved fast, they could take all the supplies they needed from the Federals in Chattanooga. Bragg wouldn't hear of it. Forrest was furious, saying: "What does he fight battles for?!"

Monday ended with Bragg immobile. He remained immobile all of Tuesday as Rosecrans collected his beaten army and built up defenses around Chattanooga, with his back to the Tennessee River. The soldiers tore down houses to obtain lumber for fortifications, leaving citizens homeless, though there were some stone buildings in the town where the people could crowd together.

* The Battle of Chickamauga Creek was over. It was a bloody, chaotic affair even by the standards of great battles. A Union brigadier general described it as "a mad, irregular battle, very much resembling guerrilla warfare on a vast scale, in which one army was bushwhacking the other, and wherein all the art and science of war went for nothing."

BACK_TO_TOP* Rosecrans, always a bit shaky, was completely unnerved by the disaster at Chickamauga. On Sunday, he had wired Halleck:

WE HAVE MET WITH A SERIOUS DISASTER; EXTENT NOT YET ASCERTAINED. ENEMY OVERWHELMED US, DROVE OUR RIGHT, PIERCED OUR CENTER, AND SCATTERED TROOPS THERE. THOMAS, WHO HAD SEVEN DIVISIONS, REMAINED INTACT AT LAST NEWS. GRANGER, WITH TWO BRIGADES, HAD GONE TO SUPPORT THOMAS ON THE LEFT, EVERY AVAILABLE RESERVE WAS USED WHEN THE MEN STAMPEDED.

Charles Dana had also wired Secretary Stanton:

CHICKAMAUGA IS AS FATAL A NAME IN OUR HISTORY AS BULL RUN.

Lincoln, who in the days before had been getting glowing promises of a great Union victory from Rosecrans, commented: "Well, Rosecrans has been whipped, as I feared. I have feared it for several days. I believe I feel trouble in the air before it comes." The President tried to encourage Rosecrans, wiring him on Sunday evening:

BE OF GOOD CHEER. WE HAVE UNABATED CONFIDENCE IN YOU AND IN YOUR SOLDIERS AND OFFICERS ... WE SHALL DO OUR UTMOST TO ASSIST YOU. SEND US YOUR PRESENT POSTING.

Rosecrans was beyond any easy encouragement. His replies were basically expressions of despair and gloom, one simply concluding:

OUR FATE IS IN THE HANDS OF GOD, IN WHOM I HOPE.

There was no doubt that the fight at Chickamauga Creek had gone badly for the Federals and severely injured Rosecrans' army. Despite that, a rational balance of the relative strengths of the two sides made the Federal position seem much better. The Confederates had been hurt just as bad, and Bragg had failed to cut off and destroy the Yankees. Although the rebels had moved into the heights on Missionary Ridge, Lookout Mountain, and Raccoon Mountain, they didn't have the strength to completely encircle and choke off the defenders.

Longstreet had argued at length with Bragg for him to take the offensive, but Bragg simply didn't feel he had the logistical capability to support an army on the move. His position was good, since with his command of the heights the Federals were only able to resupply Chattanooga by the most roundabout and inadequate path, and it seemed likely that Rosecrans would be starved out of the town sooner or later. As Bragg later wrote: "We held him at our mercy, and his destruction was only a matter of time."

However, the Federals were still in the town. As long as they held it, they not only blocked any serious rebel attempt to restore Confederate fortunes in Tennessee, they also kept a foot in the door to Georgia and Atlanta. Chickamauga Creek had been a tactical victory for the Confederacy, but the Yankees still occupied a strategic position. In fact, although Rosecrans would never completely recover from the blow to his self-confidence from Chickamauga Creek, within a few days things didn't seem so bad after all. On 23 September, Charles Dana wired Washington, telling them that Rosecrans "has determined to fight it out here at all hazards." Rosecrans still had 35,000 effectives and could hold out for a few weeks, but quick help would be welcome.

Lincoln had been trying to get reinforcements to Rosecrans, ordering Halleck to move troops from Memphis and Vicksburg, while the President personally wired Burnside to move to Rosecrans' aid. However, Burnside was focused on his own objectives and Lincoln found it difficult to change his direction. Burnside replied that he was closing in on Jonesboro, which meant that he was moving away from Rosecrans, not towards him, which provoked a rare fit of temper from the President: "Damn Jonesboro!" Burnside was apparently reluctant to abandon the people of east Tennessee to the Confederates, which would have been treacherous after the welcome he had received. Lincoln gave up trying to prod him, with the administration then realizing that Burnside was at risk, if Bragg chose to fall on him.

On the night of 23 September, Lincoln was roused out of bed for a midnight meeting called by Secretary of War Stanton. It was an indication of how seriously the crisis in Tennessee was taken that this was the only time Stanton had ever awakened the President for such an emergency conference. The meeting included the President, Stanton, Secretary of State William Seward, Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase, General Halleck, and a few lower-ranking War Department officials. Stanton pointed out that reinforcements moving from Vicksburg and Memphis would have to march across the state, which would take too much time, and so he suggested that forces be detached from the Army of the Potomac in northern Virginia and sent by rail in the meantime.

Lincoln and Halleck said that draining Meade's forces would prevent him from taking the offensive against Robert E. Lee, but Stanton replied that he saw no particular prospect that Meade intended to do so in the near future. Stanton suggested that Major General Oliver Howard's XI Corps and Major General Henry Slocum's XII Corps be sent, with Slocum to be under the command of Major General Joseph Hooker.

Hooker had been commander of the Army of the Potomac, being sidelined early in the Gettysburg campaign, and had been idle for the last few months. Stanton didn't like Hooker -- he was overly ambitious and disliked by many generals and officials -- but there was nobody else available with the necessary level of authority. In fact, when Slocum was told he would report to Hooker he would try to resign, and he would only be quieted down by being given unwritten assurances that Hooker's leash on him would be loose.

Stanton said he could get the reinforcements in the theater in five days. Lincoln was skeptical, but Seward and Chase backed Stanton up, and the President finally agreed. In fact, Lincoln probably didn't need much persuasion. Only a few days earlier, he had been writing to Meade, suggesting that if a smaller force could fight defensively against a larger one, then it seemed logical that if the Army of the Potomac remained on the defensive, parts of it could be detached for combat elsewhere.

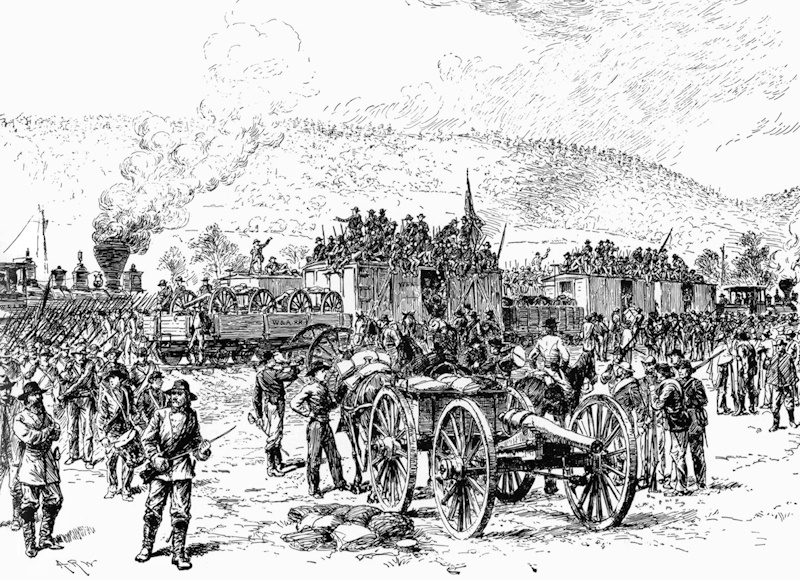

The meeting broke up at 2:00 AM. Within a half-hour Stanton was a whirlwind of action, working with everyone from state governors down to quartermaster officers to get a relief movement under way. The next day, 24 September, Stanton held a meeting with railroad officials, and the first troops left Washington on 25 September, reaching Louisville, Kentucky, on 29 September. By early October, two fully-equipped Union Army corps with a total of 20,000 men were sitting in Bridgeport, Alabama, waiting to move to relieve the defenders of Chattanooga. It was a feat of logistics unprecedented in the history of warfare, and a great accomplishment on the part of Secretary Stanton. He had something of a hysterical streak, and earlier in the conflict he had shown an inclination to fly off the handle in emergencies -- but clearly, he had learned much by that time.

Although one of the reasons Bragg had not pressed the attack on the Army of the Cumberland was the mistaken belief that Rosecrans still outnumbered him substantially, that had not been true for the first weeks of the siege of Chattanooga. Now it was. Bragg was attempting to lay a siege against a force that was bigger than his, and as more Federal reinforcements marched to Rosecrans' aid, the situation could only get worse. As for reinforcements, none were available to Bragg.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Yankees holed up in Chattanooga, as well as the Yankee officials who were moving heaven and earth to relieve them, remained extremely worried about what Bragg's forces would do next. The defenders might have been less anxious if they had known more about the condition of the rebels in the towering ridges around the town. The besiegers were in as bad or worse shape as the Yankees in the town below, having little to eat and suffering from inadequate clothing as the weather got colder. Their victory at Chickamauga Creek had bought the rebel soldiers little more than misery. Their morale plunged.

The poor morale was reflected in the quarrels of their leaders. Braxton Bragg's Army of the Tennessee had never been noted for the harmony of its leadership, but the failure of Bragg to exploit the rebel victory at Chickamauga Creek led to unprecedented antagonism, and the exit of a number of senior officers from his command.

Bragg, to no surprise, touched off the quarrel himself. Two days after the battle of Chickamauga Creek, Bragg sent stiff messages to Polk, Hindman, and Hill demanding explanations of why they had failed to carry out his orders in battle. The result was of course bitter feuding. The three generals appealed to Longstreet on 26 September to help them in their feud with Bragg. Longstreet had the most clout, was seen as dispassionate and, as a detached officer who normally reported to Lee, could also be seen as disinterested. He wasn't, not completely, writing Confederate War Secretary Seddon: "I am convinced that nothing but the hand of God can save us or help us as long as we have our present commander."

Longstreet's intervention, as could be expected, did little more than antagonize Bragg. Both Polk and Hindman were relieved of command by Bragg at the end of September. As a parting shot, Polk wrote a letter to Jefferson Davis, bitterly criticizing Bragg. Bedford Forrest left as well, but instead of being fired, he quit. The root cause was the friction between Forrest and Wheeler. On 28 September, Forrest had received a terse order from Bragg ordering Forrest to turn his men over to Wheeler's command; Forrest was given no explanation. Though he did as ordered, he also wrote a flaming protest to Bragg.

The trouble was smoothed over, with Bragg explaining that Forrest's cavalry would be returned in a short time. Forrest went on leave to visit his wife, who he had not seen for well over a year. However, while on leave, Forrest got wind of an order that placed Wheeler in charge of all cavalry in the Confederate Army of the Tennessee. That meant, at least as Forrest interpreted it, that Wheeler had now taken permanent possession of all of Forrest's men.

The intense but normally understated Forrest journeyed back to Bragg's headquarters in a mighty rage, stormed into Bragg's tent, and ranted: "I have stood by your meanness as long as I intend to! You have played the part of a damned scoundrel, and are a coward, and if you were any part of a man I would slap your jaws and force you to resent it! You may as well not issue any more orders to me, for I will not obey them ... and I say to you that if you ever try to interfere with me or cross my path it will be at the peril of your life!"

Bragg let him go unhindered, more in spite of Forrest's abuse than because of it. Bragg was too hard-headed to be much moved by such talk, even though Forrest was not a man to make idle threats. Bragg knew that Forrest was a great warrior, but not a real soldier as a military professional defined the term, and so Bragg was tolerant of Forrest's lack of discipline. The likes of Polk, Hindman, and Hill were supposed to be professionals, and Bragg held them to higher standards.

* The chaos at the head of the Confederate Army of the Tennessee caused considerable unease in Richmond. The situation was so clearly out of control that Jefferson Davis felt personally obligated to travel to Tennessee and sort things out, leaving Richmond on 6 October. There was nothing in Jefferson Davis' stiff personality that suggested he had any competence as a peacemaker -- but things had gone to the point where he couldn't make things much worse either. He arrived on 9 October and sat everyone down in a meeting, where they traded complaints about each other and bickered.

That approach going nowhere, Davis then decided to talk to the generals individually. His loyalty to Bragg was strong, but he realized that even if the antagonism towards Bragg was completely unjust, the fact remained that none of Bragg's lieutenants felt the man was fit to be their leader.

The big problem was to find a replacement. Davis had no great respect for Bragg's quarrelsome lieutenants, and did not regard them as suitable commanders of an army. He sounded out Longstreet for the assignment, but Longstreet turned down the offer, suggesting Joe Johnston as an alternative. Davis regarded Johnston as defeatist and was not happy with the idea, but there were no more preferable qualified candidates. There was nothing to do but retain Bragg. All Davis did in the end was confirm removal of D.H. Hill from Bragg's command. Hill was sent back east, likely to his relief.

These troublesome matters attended to, Davis then conducted a presidential inspection of Bragg's army and conferred with Bragg on future plans. Bragg told Davis that he was confident of eventually starving the Federals out of Chattanooga. Davis found this attitude unaggressive; Bragg quickly countered with a plan to shuttle more troops from the East and take the offensive. Davis was sympathetic to the plan, but reasonably felt he could not deplete Lee of any more troops. The idea went nowhere.

Longstreet also proposed offensive operations, if on a limited scale, to make sure that the Federal supply lines to Chattanooga were solidly cut and stayed cut. The resupply of Rosecrans' trapped army was largely an engineering problem; Longstreet knew that if the Yankees were not always competent in all the skills of warfighting, they were almost superhuman when it came to feats of military engineering, and that was the sort of problem they were guaranteed to solve. Bragg weakly agreed with Longstreet's opinions on the matter.

* Davis addressed the troops of the Army of the Tennessee on 14 October, doing his best to encourage them. He left on 17 October on his special train, swinging through the South towards Mobile, Alabama, to inspect the defenses there.

With time on his hands while the train made its way from stop to stop, Davis sorted out the particulars of some of the problems that had fallen into his lap while at Bragg's headquarters. On 23 October, he wired Bragg and Johnston to arrange the assignment of General Hardee to the command Polk had vacated in the Army of the Tennessee, while Polk took Hardee's place at the recruiting and training center at Demopolis, Alabama.

On 25 October, Davis met with Bedford Forrest. Much to Forrest's satisfaction, Davis sent a recommendation for promotion of Forrest to major general to the Confederate Congress; assigned Forrest to his own command in northern Mississippi; and arranged for the transfer to the new command of two battalions of cavalry, which had been part of Forrest's old command, and an artillery battery from the Army of the Tennessee. That was a small command for a major general, but now Forrest had greater authority -- and he not only knew how to make the best use of the resources he had, he was also ingenious at finding new resources where none seemed available.

Davis returned to Richmond on 8 November. He had seemed unusually relaxed, and spoke well and enthusiastically at his various stops. Now he was back at the seat of government, with all the pressures of the war fully focused on him once more.

BACK_TO_TOP* While Bragg and his generals quarreled, the Union was funneling reinforcements and supplies towards Chattanooga. By the first of October, the transfer of XI and XII Corps from the Army of the Potomac was well underway. More reinforcements were coming. On 23 September, Grant had wired Major General William Tecumseh Sherman to depart the Vicksburg area with two divisions for the relief of Chattanooga, and to pick up a third division that MacPherson had sent to Helena.

Sherman had been idle, a condition that the perpetually restless general was not really constructed to like, and the movement would have been welcome except for a personal tragedy -- the death of his nine-year-old son Willy from typhoid as Sherman was planning the move. He told his wife: "With Willy dies in me all real ambition." Sherman went on with his duties in a state of black depression, setting his troops in motion on foot or by railroad towards Corinth. On 11 October, he took a train with his staff and a battalion of troops towards Corinth, only to be attacked at a fortified way-station at a place named Collierville by rebel cavalry under Brigadier General James Chalmers.

Chalmers had 3,000 men and Sherman only had a fifth that number, but Sherman managed to stall for time by discussing terms of surrender with Chalmers. Reinforcements arrived and drove the Confederates off. The Yankees had got the worst of it, with over a hundred casualties to half that for the rebels; the raiders had even taken Sherman's favorite horse and one of his uniforms. The loss was slight in the bigger picture of things, and simply having seen some action did much to snap Sherman out of his funk.

Sherman reached Eastport on the Tennessee River on 19 October. By that time, he had acquired two more divisions from Major General Stephen Hurlbut in Memphis, for a total of five. At Eastport, the superlative Union logistics machine provided him with transports loaded with supplies, guarded by two Navy river gunboats. The vessels gave Sherman a reliable means of transport and support, but he had also been instructed to rebuild the Memphis & Charleston railroad across northern Mississippi and Alabama. This effort would delay the arrival of Sherman and his 17,000 men at Stephenson, Alabama to early November, but Sherman threw himself into the project.

He had another agenda in the railroad project. At one time, Sherman had demonstrated every due consideration for rebel property, but those times were over. In mid-September, Halleck had asked Sherman for his ideas on the conduct of the war, and replied in such detail that he apologized to Halleck for "so long a letter". The long letter had concluded: "I would make this war as severe as possible, and show no symptoms of tiring until the South begs for mercy ... The South has done her worst, and now is the time to pile in our blows thick and fast."

Accordingly, Sherman told his troops as they built the railroad line to live off the land. They did so enthusiastically. Sherman hoped that the foraging would render the land so barren that rebel raiders would have no means of sustenance passing through it. In fact, Sherman halfway entertained the idea of marching his army back and forth through the region until there was nothing left to steal or destroy.

* That was all very well -- at least from Sherman's point of view -- but the real focus of Federal worries in the West was Chattanooga. Rosecrans' morale was shaky, and the position of his army in Chattanooga was about the same. From the high point of Lookout Mountain, rebel artillery could easily bombard relief columns trying to move into the town by rail, river, or road. Other rebel forces held the Tennessee River more directly. The only path that was still open was a convoluted road 30 miles (48 kilometers) long that circled north around Chattanooga, finally ending up on the Tennessee to the east of the town. The road was poor at best, in some places nothing but a trail over jagged precipices, and there was no forage for the mules. The route was muddy and dangerous, and so inhospitable that thousands of mules died trying to make the trip over it. The road was inadequate for supplying a full army. Worse, it would not be able to support evacuation of that army if it came to that.

On 2 October, Joe Wheeler and his 4,000 rebel cavalrymen, including those grudgingly loaned by Forrest, descended on a Federal wagon train on its way down the road. The Confederates destroyed 300 wagons and killed all the mules. Federal troopers moved in on him, inflicting over a thousand casualties before Wheeler took the survivors back over the Tennessee on 9 October. The raid had been costly and Wheeler didn't want to try it again any time soon -- but by killing so many Yankee mules, he had done much to render the Union defense of Chattanooga even more tenuous.

Cold and hunger ground down the defenders, but the citizens of the town were worse off. They had no more food than the soldiers, and the Federals had torn down houses to built fortifications and provide firewood, leaving the people to seek refuge in a few stone buildings and in pathetic shanties. Most eventually fled the town. It took a hard-hearted soldier not to pity them. A Union officer encountered some of them on the road, "exposed to the beatings of the storms, wet and shivering with cold. I have seen much of misery consequent upon this war, but never before in so distressing a form as this."

Although Charles Dana personally liked Rosecrans, Dana was becoming frustrated by the general's indecisiveness. Rosecrans had been dealt a terrible emotional blow at Chickamauga Creek and was not showing signs of rallying. He was also engaged in a hunt for scapegoats, relieving McCook and Crittenden of command for fleeing the field at Chickamauga Creek, ignoring the fact that he had done the same himself. The two generals would later be exonerated by a board of inquiry. Dana wired Secretary Stanton:

THE PRACTICAL INCAPACITY OF THE COMMANDING GENERAL IS ASTONISHING AND IT OFTEN SEEMS DIFFICULT TO BELIEVE HIM OF SOUND MIND.

On 27 September, Dana suggested that Rosecrans be sacked, and later suggested that Pap Thomas would be an excellent choice for a replacement. Rosecrans' chief of staff, Brigadier General Garfield, was also discreetly telling people such as reporters and Treasury Secretary Chase how Rosecrans had fled the field at Chickamauga Creek, leaving Thomas to fend for himself, with Garfield present to lend a hand. That was a grossly self-serving version of events -- Garfield had essentially volunteered to go back to the fight so that Rosecrans could go to Chattanooga to organize a defense -- but there were many in Washington who were inclined to believe it. Lincoln described Rosecrans as acting "confused and stunned, like a duck hit on the head." When the President began to mock a general, it was a good sign that patience was running out.

* On 16 October, the War Department ordered General Grant to proceed to Louisville, Kentucky, where he would meet "an officer of the War Department with your orders and instructions. You will take with you your staff, etc., for immediate operations in the field."

No further explanation was given. Grant was on crutches at the time, having suffered a nasty fall off a horse while visiting New Orleans in September. He wasn't on the invalid list however, so he went upriver by steamboat to Cairo, Illinois, then went by train to Louisville by way of Indianapolis. War Secretary Stanton got on board in Indianapolis, introducing himself to Grant's staff surgeon under the mistaken impression that the Army doctor was Grant. It was a common mistake: nobody ever thought the shabby and unimpressive Grant looked much like a general.

What Stanton had to tell Grant more than made up for such a petty blunder. Although Grant had been more or less idle over the past few months, one of the bright linings of the disaster at Chickamauga Creek was that the long-standing and self-defeating command confusions in the Union Army were now being resolved. Grant's authority was expanded from his current command of the Union Army of the Tennessee to give him control of Rosecrans' Army of the Cumberland and Burnside's Army of the Ohio.

Grant now had control over the entire military machine in the West, except for Louisiana. The days when different Federal generals would move when each damn well felt like it were coming to an end. Sherman was to replace Grant in command of the Army of the Tennessee. Although the President was unhappy with Burnside for his failure to come to the aid of Rosecrans, for the time being he was left in command of the Army of the Ohio.

The immediate issue was what to do with Rosecrans. Grant's orders gave him the option of dismissing Rosecrans and replacing him with Pap Thomas. Grant had never got along well with Rosecrans, and agreed to the dismissal immediately.

On hearing reports from Charles Dana that Rosecrans meant to pull out of Chattanooga that evening, Stanton sent out messengers to find Grant that night, and presented the general with Dana's reports. Grant promptly sent a telegram to Rosecrans indicating that he was relieved of command and that Thomas should take his place, then sent a telegram to Thomas telling him to hold on "at all hazards". Thomas replied, characteristically and sincerely:

WE WILL HOLD THE TOWN TILL WE STARVE.

Grant left Louisville on 20 October, arriving in Stephenson by way of Nashville the next afternoon. There he met with Rosecrans, who was on his way out towards his home in Ohio after leaving Chattanooga quietly so as not to cause a stir. The two men had little liking for each other, but they were both determined to work for a common cause, and the short meeting was cordial. Rosecrans made a number of suggestions that Grant judged "excellent", and then went back to Ohio. Rosecrans would soon be sent to Missouri to take command there.

BACK_TO_TOP