* After the battle at Murfreesboro in late 1862, Braxton Bragg's Confederates remained in a stand-off with William Rosecrans' Federals into the new year. Come the late winter and spring, Bragg sent out cavalry forces to disrupt, with some success, Union offensive preparations.

It wasn't until early June that Rosecrans got moving in earnest, his goal being to seize Chattanooga, Tennessee, while a secondary Union force under Ambrose Burnside moved on Knoxville, up the hill country. Bragg was unable to stop the Federal offensives, with Chattanooga and Knoxville captured in early September. However, Bragg had received reinforcements and then maneuvered against Rosecrans, leading to a confrontation at Chickamauga Creek in mid-September.

* After the Battle of Murfreesboro, Tennessee, at the start of 1863, the Union Army of the Cumberland -- under the command of Major General William S. Rosecrans -- set up camp in Murfreesboro, while the Confederate Army of Tennessee -- under General Braxton Bragg -- settled down at Tullahoma, Tennessee, about 40 miles (64 kilometers) to the south.

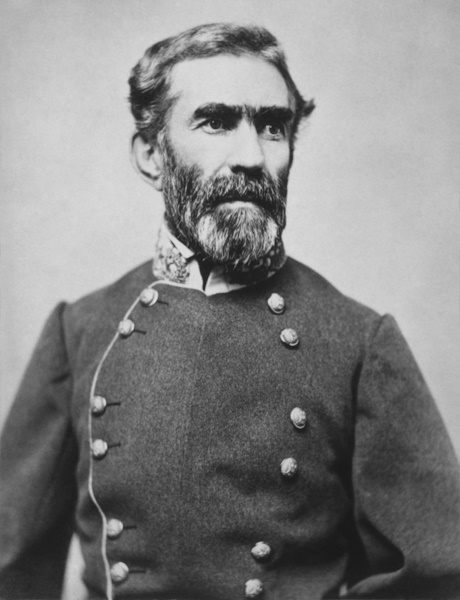

Braxton Bragg was a technically competent general, but his people-management skills left much to be desired: he wasn't easy to get along with, one particular fault being an inclination to get into quarrels with his chief lieutenants. Following the withdrawal of the Confederates from the battlefield at Murfreesboro, the quarreling got so loud that Richmond -- the Confederate capital in Virginia -- sent Joe Johnston, the senior Confederate general in the West, from Mobile, Alabama, to Tullahoma to investigate. After ten days of inspection, Johnston reported to Richmond on 3 February that the troops were "in high spirits, and as ready as ever to fight" and that Bragg had demonstrated "great vigor and skill."

It is likely that this was Johnston's sincere opinion -- he was always sympathetic to his subordinates, even one as abrasive as Braxton Bragg -- but matters were more complicated than they seemed. Lieutenant General Leonidas K. Polk had written to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, suggesting that Bragg be relieved and sent to Richmond, where his organizational skills would be valuable, and replaced as commander of the Army of Tennessee by Joe Johnston.

Johnston learned of the letter, and it did not sit well with him. Johnston had no liking for back-door politicking by generals, and he didn't get along well with Jefferson Davis either. The fact that Polk was on personal terms with Davis, the two having been classmates at West Point decades earlier, likely didn't help matters. Johnston completed his inspection on 12 February, and once more reported the condition of the men in glowing terms, praising the "great skill" of General Bragg. Johnston concluded: "I am sure that you will agree with me that the part I have borne in this investigation would render it inconsistent with my personal honor to occupy that position ... General Bragg should not be removed."

Johnston thought it would be an injury to give Bragg the axe, and an insult to then take his place. Johnston then left Tullahoma for Chattanooga, Tennessee. Davis and his Secretary of War, James Seddon, begged Johnston at length to reconsider taking charge in Bragg's place, but Johnston, thoroughly disgusted with everything, remained silent on the issue. Finally, on 12 March, while back in Mobile, Johnston received peremptory orders to go back to Tullahoma and take command anyway. He dutifully returned -- and then things took an even more unexpected turn: Bragg's wife had typhoid, and was judged unlikely to live.

Johnston indeed had to take command, since Bragg was constantly at his wife's bedside, but Johnston could not possibly order Bragg to Richmond when the poor man's family was in such trouble. The woman recovered, but by that time Johnston was down and out himself from a relapse of a wound he'd suffered in battle a year earlier. Bragg remained in command of the Army of Tennessee. He had been given a reprieve in spite of all the odds, and laid plans to carry on the war against the Yankees.

Rosecrans had let the rebel Army of the Tennessee get away at Murfreesboro, and there was going to be a rematch sooner or later. The next Federal objective in the region would be Chattanooga, the key to east Tennessee and Georgia, and Bragg wanted Rosecrans to pay dearly for it.

Strategically, however, the contest between Bragg and Rosecrans was a secondary theatre in the struggle for the West. The main issue there at the time was the Union push down the Mississippi River; if the Union took control of the river, the Confederacy would be cut in half. The key to the river was the Confederate stronghold at Vicksburg, Mississippi, under the command of Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton. Union Major General Ulysses S. Grant was determined to capture Vicksburg, devising a series of plans to that end. He wasn't making much progress for the moment, but he wasn't remotely close to giving up.

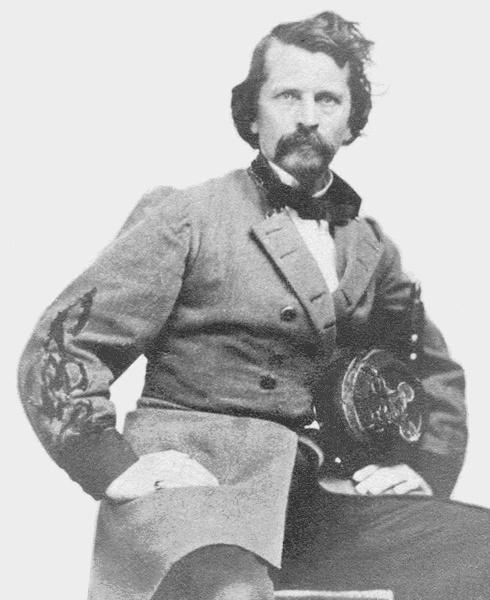

* The struggle for east Tennessee went on. Rosecrans was inactive for the moment, but Bragg's cavalry -- led by Brigadier Generals Joe Wheeler, Nathan Bedford Forrest, and John Hunt Morgan -- were doing what they could to inflict pain on the Federals, if with mixed results.

Joe Wheeler had gone off raiding Tennessee in January, and on the 13th of that month had achieved a notable success by sinking four cargo vessels and a gunboat at Harpeth Shoals, upriver from Nashville -- interrupting Federal use of the Cumberland as a supply line. Unfortunately, on 3 February he ordered a half-baked attack on a Federal outpost at Dover, well to the north, and was thrown back with serious losses; Bedford Forrest lost some of his best men and had two horses shot out from under him.

Unimpressed with Wheeler's leadership, Forrest told Wheeler to his face that he would resign before taking any more orders from him. Wheeler, having had enough for a while, took his men back to Columbia, Tennessee -- the western linchpin of Bragg's defense, on the Duck River -- to rest and refit for a time.

Wheeler was joined on 22 February by two divisions of cavalry under Major General Earl Van Dorn, detached from Pemberton's Vicksburg command to help protect the Central Tennessee line. Wheeler was assigned to protect the eastern part of the line, while Van Dorn, with the help of Forrest, was assigned to protect the west.

Van Dorn and Forrest quickly found themselves engaged with the enemy. On 4 March, Rosecrans sent two columns toward Columbia, one moving south along the rail line under Colonel John Coburn, another moving west from Murfreesboro under Major General Phil Sheridan; Sheridan was to join Coburn's column as it moved down the railroad line at a place named Thompson's Station. Unfortunately for Coburn, Van Dorn and Forrest met him there first on 5 March, taking Coburn himself and 1,200 of his men prisoner, while scattering the rest of his 3,000 troops. The rebels turned east to deal with Sheridan, but he was cautious and remained out of reach.

Forrest wasn't quite ready to go home yet. He rode his men deep into Union lines and struck at Brentwood, only 10 miles (16 kilometers) south of Nashville, on 25 March, seizing 800 prisoners and destroying a Federal supply depot, and then escaped by his well-tuned method of throwing out blows and feints to slip away in the confusion.

Elsewhere, Bragg's cavalry hadn't done quite so well. John Hunt Morgan had taken a nasty bloodying on 20 March from a smaller Yankee force at the town of Milton, about 20 miles (32 kilometers) southeast of Nashville, and would take another like it two weeks later at the nearby town of Liberty. Morgan had achieved success earlier in the war, but his star was fading. Bragg still was pleased, while Rosecrans was distressed: win or lose, Confederate cavalry were still a distraction.

BACK_TO_TOP* As spring arrived in central Tennessee, Bragg's cavalry generals continued their attempts to harass Rosecrans' army, once again with mixed results. On 10 April, Van Dorn arrived at the Federal outpost at Franklin, halfway between Nashville and his own base of operations at Columbia. The Federals were present in Franklin in strength and Van Dorn withdrew after a tentative probe. The Yankees claimed Van Dorn had failed in an all-out attack, but the general was known to have an excessive enthusiasm for the offensive that had led him to grief in the past; since there were no more than a hundred casualties on each side, it seems clear that Van Dorn was being uncharacteristically prudent.

Joe Wheeler's luck was improving. Also on 10 April, his men ambushed two Union trains, capturing 20 officers, including three of Rosecrans' staff; seizing $30,000 in Federal greenbacks; and liberating 40 Confederate prisoners. Wheeler dodged Union attempts to capture him and returned to base with only one man wounded.

By that time, Rosecrans was thoroughly fed up with being harassed. When a Colonel Abel D. Streight, in command of an Indiana regiment, proposed a Federal cavalry raid behind Bragg's lines, Rosecrans was enthusiastic. Streight planned to cut the Western & Atlantic Railroad, which ran from Atlanta to Chattanooga, which helped supply Bragg's army.

Streight was given four regiments of Midwestern infantry to press into service as cavalry, along with two companies of north Alabama Unionists who were to act as guides, giving him a total of 2,000 men. Pressing footsoldiers into service as cavalrymen was unpromising -- as was the fact that, since Rosecrans was low on horses, Streight would make do with mules. However, Streight reasoned that mules were smarter than horses and were more sure-footed, an asset in rugged terrain.

Unfortunately, while Streight tried to organize his force in Eastport, Mississippi -- nestled in the corner of the state joining Tennessee and Alabama -- he began to find the mules very troublesome. Many of his mules turned out to be infected with distemper, and a few hundred of them were unbroken two-year-olds who greatly enjoyed throwing Streight's novice cavalrymen into the dirt. Mules are indeed intelligent, but those more familiar with the beasts could have told Streight that along with such intelligence comes a degree of infuriating independent-mindedness and downright cussedness. To add to these troubles, at the last moment several hundred of the mules escaped into the countryside, braying loudly and obnoxiously to mock the Union soldiers who tried to chase them down.

In any case, on 22 April, five days behind schedule, Streight's men moved out, screened from rebel scouts by a 7,500-man force under Brigadier General Grenville M. Dodge that had marched from Corinth. The raiders made reasonable progress at first, though on the 26th 500 men deemed physically unfit to continue on the raid were sent back to Eastport, reducing Streight's numbers to 1,500.

By 30 April, Streight's column was at the foothills of the Appalachians, halfway across northern Alabama, when the rear of his column came under attack. It was Bedford Forrest, commanding a thousand men. Forrest had been riding to intercept Streight for the better part of a week, and had finally caught up with him. Streight didn't realize he outnumbered the rebels but he was at least shrewd enough to set an ambush, establishing a defensive line while his Unionist Alabamans kept Forrest's men busy. When the Alabamans broke to the rear, the rebels followed and ran into massed volleys of rifle fire and canister. The Confederates were badly bloodied and thrown back.

Another commander might have been discouraged by such a setback, but Forrest just got mad; the Yankees had taken two artillery pieces and had wounded his brother, Captain William Forrest. He threw his own cavalry after Streight, pursuing the Yankees relentlessly and giving them no rest. And so it went, for the rest of that day into the moonlight, through the next day, and into the next day. Streight laid ambushes to halt his pursuers momentarily, but the rebels would quickly rally and come on. Forrest managed to keep his own men effective by giving some of them rest while the others kept up the pressure. The rested men would then catch up with the main body, while another group got a chance to rest.

By 3 May, Streight's men had been driven through the hills to Gaylesville, almost at the Georgia border, and were so exhausted they could go no further. Forrest sent a courier to Streight to demand his surrender. The two commanders met in a parley, with Streight by no means ready to give up -- until he noticed a seemingly endless stream of rebel artillery moving up behind Forrest. It was really just a silly trick, the same two guns over and over again, going in a loop -- but Streight, likely too weary and frazzled to think clearly, fell for it, saying: "Name of God! How many guns have you got? There's 15 I've counted already!"

Forrest answered, deadpan: "I reckon that's all that's kept up." Streight went back to confer with his officers. When he heard a report that the bridge that offered his only apparent hope of escape was heavily guarded by rebel troops, he went back to Forrest and surrendered. The Confederates took their captives into Rome, Georgia, across the state border, where all, rebel and Yankee alike, were kindly treated to a feast by the local citizens.

* On the evening of 5 May, Forrest received word that another column of Yankee raiders was on the move; he led his men out in a hurry, but it turned out to be a false alarm. On 10 May he received other news: orders to report to Braxton Bragg for promotion to major general, and assignment to the command left vacant three days previously by the death of Earl Van Dorn.

On 7 May, a Columbia physician named Dr. George B. Peters had ridden his buggy to Van Dorn's headquarters, walked in, shot Van Dorn in the back of the head with a pistol, returned to his buggy, and then rode to Union lines. Van Dorn lingered until the afternoon. He was 42 years old. While some thought the murder was politically motivated, it was generally believed the general had been showing an inappropriate amount of attention to the doctor's pretty young wife. Van Dorn always had a streak of rashness and it had, it seemed, finally cost him his life.

BACK_TO_TOP* By the summer of 1863, the fortunes of the Union appeared to be very much improving. On 3 July, Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was defeated by Major General George Meade's Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg Pennsylvania, and forced to withdraw back to Virginia. The next day, 4 July, Pemberton surrendered Vicksburg to Grant, following a lightning campaign in which Pemberton was completely outmaneuvered, and then an extended siege of the city. The Union now had control of the Mississippi.

In the wake of those two victories, Union President Abraham Lincoln was to receive more good news of success from middle Tennessee -- though along with the satisfaction he got some frustration as well. While in Murfreesboro, Rosecrans had been focused on refitting his Army of the Cumberland to take the offensive, doing no more than fending off the attacks by Bragg's cavalry. Rosecrans accumulated great stockpiles of every item needed for battle and continuously harassed the War Department for more. He was a very single-minded man, obstinate and inflexible in pursuing his own goals. Once spring arrived, the War Department harassed Rosecrans to move out of Murfreesboro and take action. He replied at length, stubbornly stalling for time.

Rosecrans was inventive in thinking up strategic reasons for not moving -- for example, suggesting that if he advanced on Bragg, Bragg would simply withdraw and combine his forces those defending Vicksburg, to fall on Grant and relieve Vicksburg. Rosecrans also cited what he claimed was a rule of war, that a nation should not try to fight two decisive battles at once. Grant had been Rosecrans' superior officer not too long before and was only too familiar with Rosescrans' quirks; but Grant, normally imperturbable, was still incredulous when he heard that story.

The procrastination was not entirely Rosecrans' responsibility. In early June, Rosecrans' chief of staff, Brigadier General James A. Garfield, drew up a plan to begin an offensive; all of the other generals under Rosecrans' command disapproved of an advance, and the plan was canceled. In the meantime, the troops of the Union Army of the Cumberland grew bored and listless, "rusting away" as one of them put it.

On 16 June, Major General Henry W. Halleck -- the nominal top general in the US Army, holed up in the War Department in Washington DC -- telegraphed Rosecrans, demanding to know if he intended to move and indicating that the answers could only be YES or NO. Rosecrans asked for five days, but 21 June came and Rosecrans was still motionless. Finally, on 24 June, just as Lincoln was about ready to explode, Rosecrans sent a telegram to the War Department:

THE ARMY BEGINS TO MOVE AT 3 O'CLOCK THIS MORNING. W.S. ROSECRANS, MAJOR GENERAL.

Not counting garrisons left behind, Rosecrans had 65,000 men available for his offensive. They were organized in three corps:

There was also a reserve corps under Major General Gordon Granger, and a cavalry corps under Brigadier General Robert B. Mitchell.

Braxton Bragg had about 46,000 men to deal with this force. Along with the cavalry corps under Wheeler and Forrest already mentioned, he had a corps under Lieutenant General Polk and a corps under Major General William J. Hardee, with such reserves as he could scrape up in his headquarters at Tullahoma. The Confederates were outnumbered, but the terrain favored the defense.

Having been left unmolested by Rosecrans to that time, Bragg had labored to refit and drill his army, as well as improve his defenses. In principle, he had reason to feel confident -- but in practice, his normally sour disposition had been made worse by a bad case of boils, and his relationship with his senior generals had never been worse; he regarded them with contempt, and they returned the compliment. There was something in Braxton Bragg that bred failure, even when things otherwise might be thought to be going well.

Rosecrans, for all his slowness in getting started, was energetic once he got moving. He chose to avoid direct confrontation with Bragg's Confederates, sending out columns as feints and maneuvering to outflank the rebels. This plan was seriously threatened at the outset when rain fell out of the sky in floods on the advancing Federals. The rain was unseasonably heavy and continued for two weeks, but the troops slogged on.

The Union soldiers were encouraged at the outset by the initiative of Colonel John T. Wilder and his brigade of 1,500 cavalrymen, in Thomas's XIV Corps. Wilder had been forced to surrender to Bragg the previous September at Munfordville, Kentucky. Although he had been paroled, the incident was humiliating and Wilder had a score to settle with the rebels. The men in his brigade were actually infantry who had been pressed into service as a mounted force, but they were just as determined as their boss, and were also armed with new Spencer seven-shot repeater carbines. Wilder had paid for the carbines out of his own pocket, with his men signing up to reimburse him out of their pay, though the Army eventually provided the funds to buy the weapons.

Wilder, who had run an iron foundry before putting a uniform, was no military professional, but he was strong-willed and had a certain resourcefulness. Lacking sabres for his cavalrymen, he equipped them with long-handled hatchets. Wilder's men were mockingly known as the "Hatchet Brigade" -- and later some of them would admit they had been entirely green, with barely any concept of feeding or currying their horses. Events would still prove that if they were amateurs at horse soldiering, they had a talent for it.

The Confederate defenses were based on ridges running across the line of march of Rosecrans' army. To penetrate that defense, Rosecrans needed to seize a pass through those ridges. The most crucial one was Hoover's Gap. Wilder's men charged through the gap and drove the rebels off. The horsemen managed to get to the south end of the pass, and, backed up by four artillery pieces, held off counterattacks before

That evening Pap Thomas arrived with his troops, to find Wilder's men in heavy action against the rebels. The Yankees' Spencer carbines poured such a volume of fire on the Confederates that the rebels thought they were up against a much larger force.

Thomas was elated by this bold action, shaking Wilder's hand and announcing: "You have saved the lives of a thousand men by your gallant conduct today. I didn't expect to get this gap for three days." Wilder took about 61 casualties holding Hoover's Gap, compared to 146 casualties for the rebels, and had opened the gates to the Confederate defense north of the Duck River. Soon his men exchanged their nickname of the "Hatchet Brigade" for a new one, the "Lightning Brigade".

The rebels conducted counterattacks the next day, 25 June, but on learning that Federal troops were outflanking the Confederate divisions on the fighting line, Bragg ordered a withdrawal to Tullahoma. Polk and Hardee had their divisions back in the defenses by the late afternoon of the 28th.

Tullahoma was strongly fortified and Bragg hoped to make a stand there. However, Rosecrans had no interest in throwing his men against earthworks. After pausing to resupply on the 27 June, he continued his advance on the 28th, directing the line of march to the southeast of Tullahoma, striking for the Nashville & Chattanooga rail line, another Bragg supply line.

By the evening of the 28th, Bragg was uncertain about what to do. Polk advised retreat, though Hardee was more hopeful that they could hold their ground. Bragg decided to sleep on it, but he didn't get better news the next day. Wilder's cavalry had moved deep into his rear and had cut two branch rail lines, though they failed to cut the main line. Tullahoma was in danger of being isolated and surrounded. On the night of 30 June, Bragg gave the order to pull out and fall back below the Elk River, just north of the Alabama border.

The withdrawal was conducted professionally: Bragg had time to remove all his equipment, while Forrest and his cavalry conducted rear-guard actions. By 3 July, Forrest's troopers, having held the Yankees back until Bragg's army was safe south of the Elk, fell back themselves. A local woman shrieked at Forrest: "You great big cowardly rascal! Why don't you turn and fight like a man instead of running like a cur? I wish old Forrest was here. He'd make you fight!" Forrest was a fighter to the core and not easily intimidated, but he would later say he would have preferred to face an enemy battery than that one angry woman.

Bragg was beyond seeing any humor in the situation. "Yes, I am utterly broken down," he admitted, adding: "This is a great disaster." His troops continued their retreat into northern Alabama and then across the swollen Tennessee River, where they would be safe from immediate pursuit. He had saved his army but lost middle Tennessee. He took a train to Chattanooga so he could report to Richmond, to add one more great disaster to the several others that had just been inflicted on the Confederacy.

Rosecrans moved his army into the evacuated Confederate works at Tullahoma. He had lost only about 570 men and taken more than 1,630 prisoners. Many of the prisoners were Tennessee men; with the Federal conquest of their state, they had no further enthusiasm for fighting for the Confederacy. In contrast, Rosecrans' men -- though wet, tired, and muddy -- were enthusiastic about their relatively bloodless victory. Rosecrans himself went back to accumulating supplies and preparing his next move. This time, he didn't intend to wait so long. Chattanooga was a prime target, and he was determined to take it.

Washington DC was still unhappy that he stopped at all. The Confederacy had been dealt severe blows in the first week of July, and it seemed entirely possible to Lincoln and his people that if the pressure were kept up, the rebellion might be ended in a matter of months. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton needled Rosecrans in a telegram:

YOU AND YOUR NOBLE ARMY NOW HAVE THE CHANCE TO GIVE THE FINISHING BLOW TO THE REBELLION. WILL YOU NEGLECT THE CHANCE?

Rosecrans felt with fair reason that the prod was unjust after the significant gains his army had obtained for the Union. His reply had a pained and indignant tone:

I BEG IN BEHALF OF THIS ARMY THAT THE WAR DEPARTMENT MAY NOT OVERLOOK SO GREAT AN EVENT BECAUSE IT IS NOT WRITTEN IN LETTERS OF BLOOD.

The letters of blood would be written in the near future.

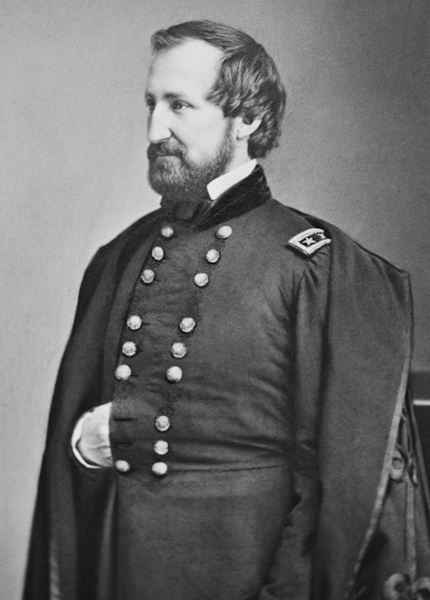

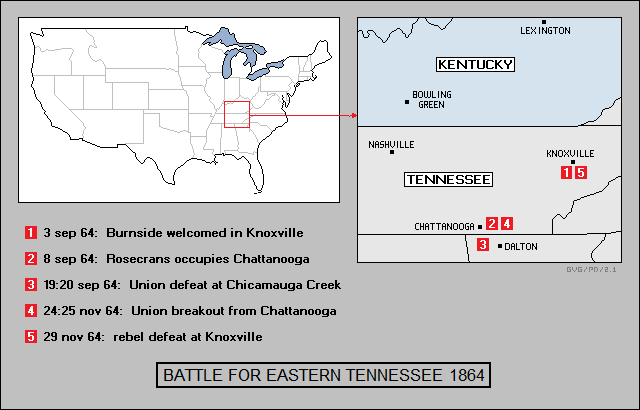

BACK_TO_TOP* In early June, as Rosecrans was preparing his movement south in central Tennessee, Union Major General Ambrose E. Burnside, in command of the Union Army of the Ohio, was assembling forces for an offensive of his own. He was to drive into the hill country of east Tennessee, his specific objective being the liberation of Knoxville. The Unionist citizens of that region had long been waiting for liberation from Confederate authority, and that goal was near and dear to Lincoln's heart.

Burnside had been delayed by detachment of some of his troops to help in the fight for Vicksburg. He brought garrison troops from places like Cincinnati as replacements, but these men were green and needed training before they would be ready for offensive operations. Burnside was a decent, likeable, earnest man -- but wasn't the most competent general, with an unfortunate history of military bungling. Whatever his other deficiencies, he was not lacking in aggressiveness, and on 14 June he sent a column of 1,500 cavalry plus mounted infantry under Colonel William P. Sanders into east Tennessee to scout out the region and disrupt the Confederates there. Sanders and his men returned on 23 June, having had considerable success in all their objectives. Sanders reported that the friendliness of the locals was a great help.

Encouraged, Burnside wanted to move quickly, but then events took an unexpected turn. John Hunt Morgan showed up in the Federal rear, leading 2,500 cavalry on a wide-ranging raid. Morgan had proposed the raid before Rosecrans began his offensive and Bragg had agreed, since it promised to disrupt Rosecrans' lines of communications and supply. Morgan was enthusiastic enough to even suggest that he and his men go north of the Ohio, but Bragg turned him down, since he wanted Morgan to be available if and when Rosecrans decided to move.

Morgan had no intention of obeying. He had enjoyed no great and glorious successes in recent months, and he felt that the only way to seriously disrupt Federal plans was to take bold actions. Morgan and his troopers crossed the Cumberland into the heart of Kentucky on 2 July 1863, slipping past a barrier of 10,000 Union soldiers. His command included four of his brothers and a brother-in-law. After attacking Union outposts with mixed results and losing one of his brothers in a fight, Morgan and his raiders crossed the Ohio on 8 July, using a pair of stolen steamers. They then rode a zigzag course east across Ohio, raising consternation and alarm all around.

Morgan succeeded in disrupting Federal plans for an offensive into east Tennessee, which at least made Bragg's withdrawal from Tullahoma much less complicated, and also succeeded in stirring up a troublesome hornet's nest. Homegrown militias were no great threat, but even in clashes with such weak foes Morgan took casualties he couldn't afford. They also slowed him down while stronger Union forces converged on him.

By mid-July, Morgan and his men were exhausted and desperate to escape south across the Ohio. When they tried to ford the river on 18 July, they discovered it was swollen by the heavy rains that had drenched the region, and found a few hundred Union troops blocking their way. Morgan decided to wait until the next morning to attack, but when the sun came up it turned out that the outnumbered Federal infantry had quietly and sensibly pulled out. That didn't give him much relief, since he was then attacked by 5,000 Union cavalry backed up by a gunboat. Morgan lost about half his command, most of them captured, and led the rest off in near-rout. About 300 of the survivors managed to ford the river that afternoon, but as a proper leader Morgan did not wish to cross until all his men had gone over to safety.

The Yankees pounced on him again before he could get everyone across; Morgan and the handful of men still remaining with him were finally chased down and forced to surrender on 26 July, only about 50 miles (80 kilometers) away from Pittsburgh. The captives were taken back to Cincinnati. Burnside announced that Morgan and his senior officers were ineligible for parole. Acting on false reports that Abel Streight had been sent to a criminal prison after his surrender in Alabama, the Ohio state authorities ordered them confined in the state penitentiary; there they were dressed in convict clothes, and much to their outrage their beards and hair were shaved off. Eventually the governor of Ohio apologized for this last action, saying it was a bureaucratic fumble, but that did little to ease their indignation.

Although Morgan had inconvenienced Burnside, loss of almost the entire raiding party was a stiff price to pay. The raid had also done much to dampen antiwar sympathy north of the Ohio. While Morgan had hoped that "Copperheads" -- pro-Confederate Union citizens -- would come to his aid, even the most extreme among them had not dared to take such a step. Many others who had been wavering in their loyalty to the Union cause found their resolve stiffened by the threat, real or imaginary, Morgan had posed to their communities.

* Ambrose Burnside always tried his best to do things right, but often seemed to bumble it in the end. However, even though John Hunt Morgan's raid into Kentucky and Ohio had delayed Burnside's move into east Tennessee, in the end Morgan was caught and his command scattered. Burnside had every reason to be happy with the way things had turned out.

The capture of Morgan didn't mean that the stream of telegrams from Halleck and the War Department nagging Burnside to GET GOING slowed down. Burnside finally moved out on 15 August 1863, with 24,000 men in three divisions with supporting cavalry. Opposing him were scattered rebel forces under Major General Simon Bolivar Buckner, whose force had been depleted by sending troops to assist Bragg in the fight against Rosecrans.

The most direct route into east Tennessee was through the Cumberland Gap, which the Federals had been forced to abandon when Bragg moved northward the previous fall. There were about 2,500 rebels in the Cumberland Gap, under the command of Brigadier General John W. Frazer. The assumption was that Frazer would be able to delay any Federal move until Confederate reinforcements arrived.

Burnside had no interest in trying to push directly through the Cumberland Gap. He sent one division through the mountains to the north to make a flanking attack on the gap, while the other two divisions went through the mountains to the south towards Knoxville. The mountain paths were painfully rugged, but Burnside had sensibly acquired pack mules for transport. It was still tough going; mules and sometimes their drivers fell off the paths through the mountains, to be killed as they tumbled down the rocky slopes. One Union soldier wrote: "If this is the kind of country we are fighting for, I am in favor of letting the rebs take their land."

Despite the difficulty of the terrain, Burnside's men faced little or no opposition and made excellent progress. One of the columns reached Knoxville on 2 September, and on 3 September 1863 Burnside himself rode into the city at the head of two divisions of infantry. The citizens applauded him enthusiastically. When a Union soldier set up a banner on the building that Burnside selected as his headquarters, the crowd went wild, the soldier writing later: "Shout after shout rent the air. Old men and gray-haired matrons took each other by the hand and laughed, shook and cried, all at the same time. Young men and maidens were uproarious, and little children were 'clean gone crazy'."

Burnside was swept up in the emotion, trading handshakes with two of his generals inside the building while tears ran down their cheeks. The whole scene was more like a Fourth of July celebration than a battle. Burnside was a star among the citizens of the city. Whatever failings he had as a general, he at least looked the part; he was a big man who cut a good figure, with incredible side whiskers. The locals were impressed, one calling him a "show general", commenting: "Not that he made any show, he was naturally that."

It was the brightest moment of Burnside's checkered military career, and he was delighted with his unaccustomed success. On 6 September, he sent a brigade of cavalry north towards Cumberland Gap. The brigade arrived the next day, and the cavalry commander demanded the surrender of the rebels. General Frazer refused. On the 8th, the division that had been sent north through the mountains arrived as well, and a second request was made for Frazer to surrender, which was also refused. In the meantime, Burnside had left Knoxville with an infantry brigade. He arrived on the 9th, making another request for surrender. Frazer finally decided to call it quits and gave up. Burnside sent his forces further east to complete the elimination of all Confederate authority in east Tennessee.

BACK_TO_TOP* On 16 August, after a short rest, Rosecrans' forces resumed the advance on Chattanooga, Tennessee. The terrain was extremely rugged and the Confederates felt confident that they could thwart the Federals. However, when Rosecrans was in good form he could be a very tricky opponent, and he managed to thoroughly confuse the defenders by sending three brigades up the north bank of the Tennessee River to put on as noisy a show as possible. Special details pounded on barrels and threw bits of plank into the river to convince rebel scouts that boats were being built for a large-scale river crossing, and on 21 August Federal gunners shelled Chattanooga itself, sinking a steamboat at the riverfront landing and disabling another.

In the meantime, Rosecrans kept the main body of his force hidden. His deceptions worked perfectly. 50 miles (80 kilometers) downstream from Chattanooga, just south of where the Tennessee crossed the state line into Alabama, Braxton Bragg had posted a brigade on the north side of the river to block the crossing at Bridgeport. In response to the demonstrations upstream, Bragg pulled the brigade out to deal with the supposed threat.

Rosecrans moved swiftly, throwing pontoons over the river and marching Thomas' corps across at Bridgeport; McCook's corps across at Caperton's Ferry, 12 miles (19 kilometers) downstream; and Crittenden's corps across at Shellmound, 10 miles (16 kilometers) upstream. Except for the three brigades engaged in continued deceptions plus a reserve division, the entire Union Army of the Cumberland was across the Tennessee by 4 September, complete with a wagon train carrying enough supplies and ammunition for several weeks of offensive operations. There was little rebel resistance to the crossings.

Of course, Rosecrans now had new obstacles in his path, in the form of three high ridges that blocked his advance. The first was Raccoon Mountain; backed up by Lookout Mountain; and then finally Missionary Ridge. Rosecrans had planned accordingly, and had detailed companies with long ropes to help pull cannons and wagons up steep roads.

The most important thing was to move quickly. McCook's column moved to hook southeast below the southern end of Raccoon Mountain, though Winston Gap to cross Lookout Mountain, and then due east into Georgia at the town of Alpine. Thomas' column went directly over Raccoon Mountain and then into Steven's Gap in the middle of Lookout Mountain, targeting the town of Lafayette, Georgia. These two columns threatened Bragg's vulnerable rail line towards Atlanta, while Crittenden's moved west along the railroad between the river and the mountains towards Chattanooga.

Rosecrans was aware that dividing his army into three columns meant that they could be destroyed by parts by an alert enemy. Most of Rosecrans' cavalry were accordingly assigned to precede McCook's column, which was the most isolated and at the greatest risk, while one brigade scouted ahead of Crittenden's column. Thomas' column had no cavalry, but it was the biggest, with 22,000 men, and could presumably take care of itself. Rosecrans accompanied Thomas, since it gave Rosecrans a central location in the advance to keep track of matters. It also gave Rosecrans the opportunity to keep up a little pressure on Thomas -- who was an excellent officer, but whose unexciteable nature sometimes meant a lack of haste.

The scheme worked perfectly. Rebel forces, faced with being cut off, pulled out of Chattanooga on 8 September, retreating to Rossville just across the state line into Georgia where they could block a gap in Missionary Ridge. Crittenden's corps moved into Chattanooga unopposed the next day. The Federals were triumphant, their morale boosted by the grandeur of the scenery through which they moved. Rosecrans was in high spirits.

Confederate deserters coming into Union lines reported to Federal officers that rebel forces were demoralized and disorganized. Rosecrans appeared to believe these reports, despite the famous shiftiness of Confederate deserters -- but many of them were surrendering on orders from their superiors and carrying well-rehearsed stories. Rosecrans heard what he wanted to hear.

BACK_TO_TOP* Rosecrans' trickery had driven Braxton Bragg out of Chattanooga, but Bragg wasn't panicked by any means; in fact, he was now laying a trap for Rosecrans. While Rosecrans had been building up supplies, Bragg had made preparations of his own, for example in June sending troops to work at farms to ensure that the bumper wheat crop was brought in to provide his troops with bread when the time came to fight.

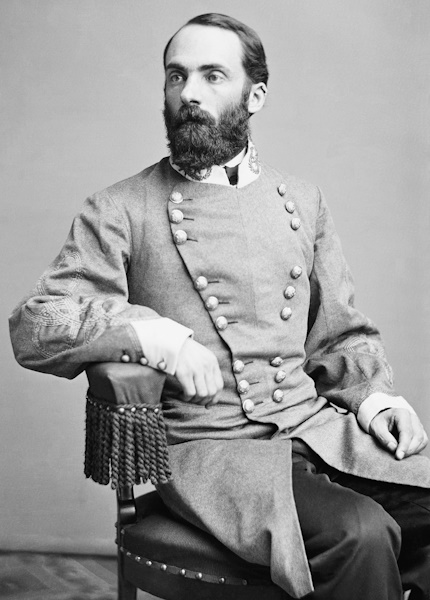

Bragg had also been receiving assistance, two "fighting generals" having been added to his command. Daniel Harvey Hill, who had been a lieutenant in Bragg's battery in the Mexican War, had been promoted to lieutenant general and sent west in mid-July from North Carolina to replace William Hardee as corps commander, Hardee having been detached to manage the demoralized herd of parolees released by the Federals after the fall of Vicksburg. Major General Thomas C. Hindman, a tough fighter, also arrived from Arkansas in mid-August, to become a division commander in Polk's corps.

Fighting commanders were all very good, but they needed troops to fight with. More soldiers were arriving. One of the silver linings of the defeats that the Confederacy had suffered that summer was that forces were now available for action elsewhere. The other side of the coin was that the Confederacy could not face more defeats any time soon. Bragg was receiving reinforcements in surprisingly large numbers.

Jefferson Davis had called a conference in late August to discuss the Confederacy's dire military situation. With disasters flaring up everywhere, Davis was hard-pressed to find the resources to deal with any one of them, let alone all. However, for the moment the Yankees were more or less inert along the Mississippi and in the East, and so Davis was able to divert forces to assist Bragg.

Major General Buckner, pulling out of east Tennessee ahead of Burnside's far superior forces, added 8,000 men to the ranks of the Confederate Army of the Tennessee, with Buckner placed in charge of a third corps of the Army of the Tennessee. With Grant's forces reduced and idle in Mississippi, Joe Johnston detached 9,000 men under Major Generals John C. Breckinridge and W.H.T. Walker, to be followed by a second installment of 2,500 more. Breckenridge became a division commander under Hill, while Walker was put in charge of a reserve corps.

Robert E. Lee was not enthusiastic about shifting forces to Bragg since he wanted to take the offensive against the Federals again -- but his voice now carried less weight in council than it had before Gettysburg, and so Bragg would get his reinforcements. Jefferson Davis wanted to send Lee west as well to take command of the Confederate Army of the Tennessee, but Lee declined, saying that Bragg as the officer on the spot would have a much better grasp of the battlefield situation.

On 8 September, the day before the Yankees occupied Chattanooga, General James Longstreet, one of Lee's main lieutenants, and his 12,000 men broke camp to be moved by railroad from northern Virginia to reinforce Bragg. It was a difficult operation. There had actually been a reasonable rail line for the journey a few weeks earlier, but it went through Knoxville, now in the hands of Ambrose Burnside. As a result, the move was clumsy and roundabout, made all the worse because the Confederacy's railroads were falling apart. One of Longstreet's officers commented: "Never before were such crazy cars used for hauling good soldiers." The move would take the better part of two weeks, and about half the reinforcements would get there too late.

Even if only half of Longstreet's 12,000 men arrived, that still gave Bragg a total of almost 70,000 men for operations, with Longstreet in command of yet another corps in Bragg's army. Although Rosecrans had 80,000 men in his command, a good proportion of them were guarding supply lines and otherwise holding down the rear. Bragg stood a good chance of actually outnumbering Rosecrans on the battlefield, a rare circumstance for a Confederate general.

However, Bragg did not feel confident. When D.H. Hill arrived, he had expected to be greeted warmly by his old commander, but found Bragg taciturn, gloomy, and nervous. In fact, Bragg's health, never good, was steadily growing worse. Though he had few admirers, a sympathetic soul observed that Bragg's biggest problem was that he was often in the saddle when he should have been in bed. Bragg was also seriously plagued by his bad relationships with Polk and most of his other lieutenants, and by the past history of defeats suffered by the Army of the Tennessee. Even after being bolstered by waves of reinforcements, Bragg simply could not quite accept that he might really win a battle. Hill was astounded by Bragg's lack of intelligence on Yankee movements and intentions, with Hill finding the battle planning at Bragg's headquarters "haphazard".

* In contrast to Bragg, who lacked confidence, Rosecrans was thinking he was invincible. After taking Chattanooga, Pap Thomas had suggested consolidating their gains to make sure the Army of the Cumberland was properly supported for further offensive actions south. Rosecrans wouldn't hear of it. No doubt he knew that if he stopped again, Halleck would immediately send telegram after telegram to tell him to get going again, but Rosecrans was also extremely excited, thinking he was closing in for the kill. His columns were still on the march, chasing what he believed was an enemy in flight. He thought if he could keep up the pressure on Bragg, the Union Army of the Cumberland would quickly be in Atlanta, or even all the way to the seacoast.

In reality, Bragg was holding a line from Lee & Gordon's Mill, on Chickamauga Creek south on the from Rossville, to Lafayette, about 25 miles (40 kilometers) south of Chattanooga, with the line directly in the path of Thomas' force. Forrest's troopers were operating to the north of the line, keeping track of Crittenden's force, while Wheeler's cavalry were operating to the south, tracking McCook's column.

Bragg intended to concentrate his forces to trap Thomas' corps and destroy it, with the terrain providing a convenient trap. A ridge named Pigeon Mountain broke off from Lookout Mountain from the south, running in front of Lafayette and wrapping around the southern end of Missionary Ridge to create a dead-end valley known as McLemore's Cove, through which Chickamauga Creek ran. Thomas and his men were advancing over Missionary Ridge into McLemore's Cove, headed toward a break in Pigeon Mountain known as Dug's Gap. Bragg hoped to box the Federals inside McLemore's Cove and then wipe them out.

This operation involved sending out two columns of troops. One, a division from D.H. Hill's corps and led by the tough Irish fighter Pat Cleburne, was to plug up Dug's Gap and engage the Federals. With Thomas and his men preoccupied with the fight in front of them, a division under Hindman would move down Chickamauga Creek and hit the Yankees in the flank and rear.

Hindman's men moved out in the dark, and by the time the sun came up on 10 September they were a few miles away from the head of Thomas' column and were ready to strike. At this point Bragg's disastrous lack of "people skills" began to make itself felt.

Hindman waited for word that Cleburne had made contact before striking, but he waited and waited and heard nothing. Hindman finally got a message from D.H. Hill, who claimed that he hadn't heard anything about the move until sunup and added that he wasn't in a position to attack quickly anyway, since Cleburne was sick in bed and several regiments had been detached anyway. Apparently Bragg had simply issued orders and assumed, without checking on them, that they would be followed to the letter. On finding out that Hindman hadn't moved, Bragg sent orders for him to hurry up, since Crittenden's column was now moving through Rossville, directly in Hindman's rear. That had the exactly opposite result from what Bragg expected, since Hindman, who could not have failed to reflect while he had time on his hands that Bragg's plans seemed half-baked, now realized he was in a position to be surrounded and destroyed himself.

The next morning, Hindman pulled out the way he had come in. Bragg sorted out the command confusion with D.H. Hill, and Cleburne went forward through Dug's Gap. Bragg sent Buckner and his troops to back up Hindman and get him to move, and finally the entire trap was working the way it was supposed to. The only problem was that there was nobody there to trap. Thomas had finally taken notice of the movements of the Confederates and pulled his lead division back out of McLemore's Cove. Bragg was furious, and characteristically traded accusations with Hindman and Hill. They were now getting a full education of how things were done in the Confederate Army of the Tennessee.

* There was no hope of trapping Thomas now, so Bragg decided to try the same trick on Crittenden's column to the north. Crittenden had split his forces, with one division taking control of Lee & Gordon's Mill and the other two moving against the railroad line to Atlanta.

Leonidas Polk had withdrawn his corps in front of Crittenden's advance, but Bragg sent him cavalry reinforcements under Walker and ordered him to attack Crittenden's men at Lee & Gordon's Mill on 13 September. Polk protested that Crittenden had taken alarm and pulled his other two divisions back to that location, but Bragg pointed out that the Federals were still outnumbered, and re-emphasized the order to attack.

Bragg and Polk simply did not ever get along. Bragg rode up that morning to see how the battle was going; he arrived at midmorning and found out that it wasn't. Enraged, he finally organized Polk, Walker, and Buckner to move out in an assault at noon on 13 September, only to find out there were no Yankees to assault. Crittenden, like Thomas, had become aware of the rebels fumbling around in front of him and pulled back over Missionary Ridge. In a black mood, Bragg decided to concentrate his forces at Lafayette and wait for developments.

By that time, Rosecrans was entirely aware that there was an aggressive and reinforced rebel army in front of him, with intelligence filtering in that Longstreet was moving west on the railroads with more reinforcements. Rosecrans ordered Thomas and McCook to bring their columns northwest out of imminent danger and link up with Crittenden's men near Lee & Gordon's Mill, on Chickamauga Creek. The move was difficult in the rugged terrain, with Rosecrans becoming more frantic by the hour. He was angry that Burnside had decided to move east through Kentucky instead of sweeping south towards Chattanooga to link up with the Army of the Cumberland -- though in reality Burnside had been encouraged to change plans by glowing reports of Rosecrans' easy successes.

Bragg began to concentrate his own forces on the east bank of Chickamauga Creek. He wired Richmond:

ENEMY HAS RETIRED BEFORE US AT ALL POINTS. WE SHALL NOW TURN ON HIM IN THE DIRECTION OF CHATTANOOGA.BACK_TO_TOP