* Into the fall, General Grant gradually relieved Bragg's grasp on Chattanooga, allowing Union reinforcements to flow in. Near the end of November, the Federals were ready to move -- and in a day's fighting, they drove the rebels off with a wild charge up the steep slopes of Lookout Mountain. The door to north Georgia was opened. A Confederate force that had been detached to deal with Burnside in Knoxville came to ruin there, resulting in a humiliating defeat for the rebels.

* Grant arrived in Chattanooga on horseback on 23 October, with his crutches still strapped to his saddle. Matters seemed dismal, with soldiers catching and eating dogs and whatever else they could get their hands on, while the Confederates stared down the besieged Yankees from the heights around the city. The Federals in the town were also outnumbered, with 45,000 men to Bragg's 70,000, though that didn't take into account the reinforcements under Hooker at Bridgeport, and those under Sherman then moving eastward.

Despite the difficulties, the mood at headquarters was upbeat. Thomas had done wonders in creating a sense of order, and plans for lifting the siege had been drafted by the chief engineer of the Army of the Cumberland, Brigadier General William F. "Baldy" Smith, even before the exit of Rosecrans. Smith had originally been an officer of the Army of the Potomac but had been shipped west because of his inclination to quarrel. Fortunately, Smith was a competent military engineer, and Grant was impressed by his plans. Grant simply added his now-considerable authority to the effort. When Grant took a hand in things, they got done.

Just west of Chattanooga, the Tennessee River flows through a southerly hairpin turn, looping around to form "Moccasin Point" on one side, and brushing the northern end of Lookout Mountain on the other. It then loops north again around Raccoon Mountain. There was a road from Bridgeport, Alabama that crossed the Tennessee at a place named Kelley's Ferry; cut through a pass named Cummings Gap in Raccoon Mountain; crossed the Tennessee again at a place named Brown's Ferry; cut across the top of Moccasin Point; and then led into Chattanooga over a pontoon bridge. It offered a straightforward route into the town to keep it supplied and reinforced.

The only problem was that the rebels were in the way. Smith's plan envisioned an attack by Hooker's force under cover of darkness northward along the east slope of Raccoon Mountain, while a combat team from the Army of the Cumberland floated silently downstream in pontoon boats to overwhelm Confederate pickets at Brown's Ferry. Once the team was in place, they would use their pontoon boats to throw up a bridge, and a larger force would cross the river to help clean out the rebels in the area. The pontoon boats and elements of the bridge were already under construction.

Grant gave the formal go-ahead, ordering the plan to be put into effect immediately. In the dark hours of the morning of 27 October, 1,500 Federals floated quietly downstream in 60 pontoon floats on the Tennessee's strong current. They overwhelmed the Confederate pickets at Brown's Ferry, set up a defensive perimeter, and started setting up the pontoon bridge. The Confederate brigade holding the area tried to throw the Yankees out when the sun came up, but was driven off. The Federals only suffered 38 casualties in the operation, including six killed. The pontoon bridge was completed by midmorning, and reinforcements from Chattanooga began to pour across. Hooker was also advancing from the south with two divisions, having left two other divisions along the route to ensure security. The rebel brigade prudently skedaddled back to Confederate lines.

Hooker and his two divisions arrived at Kelley's Ford the next day, 28 October, and Western and Eastern soldiers greeted each other enthusiastically. Unfortunately the geniality would not last, with rivalries between informal Westerners and the tightly-drilled Easterners leading over the next few weeks to jeers, along with the occasional scuffle. That was just human nature and was of little importance. Grant wired Halleck:

THE QUESTION OF SUPPLIES MAY NOW BE REGARDED AS SETTLED. IF THE REBELS GIVE US ONE WEEK MORE TIME I THINK ALL DANGER OF LOSING TERRITORY NOW HELD BY US WILL HAVE PASSED AWAY, AND PREPARATIONS MAY COMMENCE FOR OFFENSIVE OPERATIONS.

* Grant was getting a little ahead of himself, but not by much. One of the divisions that Hooker had left behind to guard his rear, under Brigadier General John W. Geary -- a towering man, a veteran of the Mexican War, the first mayor of San Francisco and a territorial governor of Kansas -- had deployed at Wauhatchie, down the valley between Raccoon and Lookout Mountains and roughly facing Cummings Gap.

Longstreet had been delayed in his plans to cut the Union supply line to Chattanooga by foul weather, and the Federals had beaten him to the punch. Longstreet still had fight in him, and decided to attack Geary's division that night. Fighting broke out about midnight, with a division of about 4,000 rebels attacking about 5,000 Federals. The odds were somewhat long and Longstreet had hoped to have a second division available for the assault, but typically Bragg had countermanded the marching orders for the second division without telling Longstreet.

Hooker, alarmed by the commotion to the south, dispatched one the two divisions with him, under Major General Carl Schurz, to go to Geary's assistance. Hooker was prudent but over-reacting. Even though there was a full moon and clear skies, night attacks without means of battlefield illumination are very troublesome and dangerous, often involving a fair amount of shooting at one's brethren. The Federals were in defensive positions and all they had to do was sit tight and shoot at anything moving about in front of them: the odds were good the target was an enemy.

The Confederates, in contrast, had difficulty even figuring out which way they were going. Their confusion was apparently aggravated when about 200 fear-crazed mules from Geary's division broke loose in the shooting and the dark and noisily stampeded towards the rebels, who thought they were being attacked by cavalry and stampeded in turn. With the arrival of Schurz with his division, the Confederates found themselves being hammered, and decided they'd had enough. By about 04:00 AM, they had all left the field of battle.

Later on, an Ohio soldier would immortalize the battle with a parody of Lord Tennyson titled CHARGE OF THE MULE BRIGADE, which in part went as follows:

"Forward, the Mule Brigade; Charge for the rebs!" they neighed. Straight for the Georgia troops Broke the two hundred.

The story about the effect of the mule stampede may have been somewhat exaggerated after the fact, but it is true that the quartermaster with ultimate authority over the mules did write Grant: "I respectfully request that the mules, for their gallantry in this action, may have conferred on them the brevet rank of horses."

* In fact, the whole relief operation left the Federals generally in very good humor. They had suffered about 450 casualties and inflicted about twice that many, including a good haul of prisoners. John Geary was not celebrating, however, since one of the dead was his own son, shot while commanding a battery of artillery.

The relief effort was completed at precisely the right time, since the Yankee soldiers in Chattanooga had just completely run out of food. On 30 October, a little steamboat that had been put together by Hooker's engineers at Bridgeport, appropriately christened the CHATTANOOGA, docked at Kelley's Ford, towing two barges with 40,000 rations and forage for such horses and mules as were still alive. The new supply route was called the "Cracker Line" in honor of the supplies of hardtack that flowed over it, and could support both the Army of the Cumberland and the reinforcements now available to help them spring out of their encirclement. The cry went up: "Full rations, boys! Three cheers for the Cracker Line!"

The depression that had gripped the hungry soldiers in Chattanooga began to fade. Their situation still remained difficult. There was no way to provide all the supplies needed using the river route. The Union logistical machine went to work creating a rail network that could flood the town with everything needed.

BACK_TO_TOP* While the Union effort to relieve Chattanooga had the effect of making the Yankees there much more of a threat to the Confederates than the Confederates were to them, Braxton Bragg wasn't in a position to do much about it; he just didn't have the resources. In fact, instead of being reinforced, Bragg was sending troops away. The presence of Union forces in Chattanooga was intolerable, not only because of the town's strategic location, but because it was the gateway to Georgia and Atlanta -- however, the presence of Burnside and his force in Knoxville was just as intolerable, since it fractured the hold of the Confederacy on the mountain region.

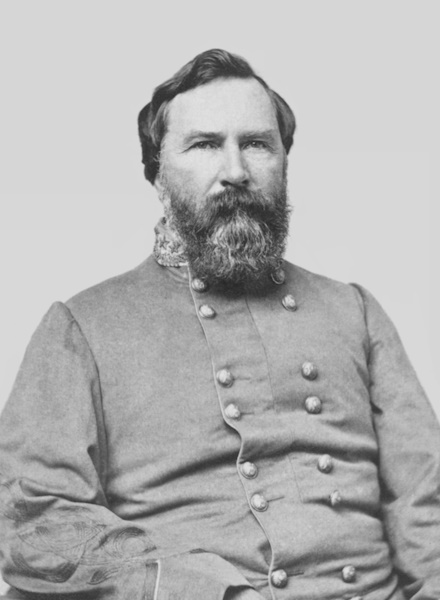

During Jefferson Davis's tour of the South, Davis had sent Bragg a letter with a suggestion that Longstreet and his two divisions be sent to deal with Burnside, with Wheeler's cavalry in support. That gave Longstreet a total of about 15,000 men to evict the 25,000 under Burnside. Longstreet moved out with his troops on 4 November.

Longstreet was unsurprisingly gloomy over his assignment. He saw no sense in dividing Confederate resources in the face of superior Union forces, to fight two battles from a position of inferiority. He told Major General Buckner: "This was to be the fate of our army -- to wait till all good opportunities had passed, and then in desperation to seize upon the least favorable one."

Longstreet had also been thoroughly infected with the demoralization and irritability of Bragg's command: Longstreet had become used to fighting for Lee, who was all that Bragg was not, and the contrast was discouraging. In fact, it appears that Bragg, who was perfectly aware of that Longstreet had no great regard for him, ordered the move partly just to get rid of him, whose stubbornness was low-key but unyielding. On 31 October, Bragg had written Jefferson Davis that Longstreet's absence would "be a great relief to me."

Longstreet hoped to move swiftly and destroy Burnside's forces by parts, since that was the only way his smaller force could defeat a larger. However, due to supply problems, compounded by the destruction of bridges in the rough and mountainous terrain, fast movement was impossible. The locomotives available were extremely decrepit, while food and cold-weather gear were very scarce. Longstreet and Bragg traded angry messages. Much later Longstreet recollected: "Thus, we found ourselves in a strange country, not as much as a day's rations on hand, with hardly enough land transportation for ordinary camp equipment, the enemy in front to be captured, and our friends in the rear putting in their paper bullets." He concluded: "It began to look more like a campaign against Longstreet than against Burnside."

* Burnside was entirely aware of Longstreet's movements. Grant was being prodded by the War Department to send help to Burnside, but Grant had his hands full with Chattanooga, and Burnside didn't seem particularly worried anyway. In fact, Burnside told Grant that the most sensible thing he, Burnside, could do was to engage Longstreet outside of Knoxville and then simply withdraw slowly to the city's defenses. That would keep Longstreet busy and separated from Bragg for as long as possible. Although Burnside was aware that he had a much larger force than Longstreet, he saw no reason to try to wipe the rebels out: if, when the Federals broke out of Chattanooga, Longstreet's troops would be isolated and forced to withdraw anyway.

Burnside accordingly dangled his force in front of Longstreet. Joe Wheeler's cavalry tried to maneuver around the Federals, but Union cavalry under Brigadier General William P. Sanders managed to frustrate them. Longstreet tried to repeatedly flank Burnside's force as it withdrew, leading to a confrontation in the mud and rain on 16 November at Campbell's Station, about 15 miles (24 kilometers) to the west of Knoxville. Confederates attacks were clumsy and uncoordinated; the fight ended up being an artillery duel, with a loss of about 300 Federals and 174 rebels. Burnside was able to continue his withdrawal, covered by Sanders' cavalry, and pulled into the defenses of Knoxville on 17 November. Sanders was killed by a rebel sharpshooter during a skirmish the next day.

Longstreet arrived before Knoxville and found the defenses thoroughly solid. For the moment, he probed and inspected the fortifications, trying to figure out what to do next.

BACK_TO_TOP* Life in Chattanooga was idle and quiet while the Union tried to get the pieces in place for offensive action. There was fraternization between the pickets, as was likely to happen under such circumstances. Tennessee Private Sam Watkins -- a commonsense observer of life at the bottom of the Confederate States Army, whose recollections of the fighting would become well-known -- related how he had seen a Yankee soldier strike up an acquaintance with a rebel sergeant, with the two men trading items and stories. Later on he found out that the Yankee was none other than Colonel John T. Wilder of the Lightning Brigade, scouting out possible river crossings.

Grant went near the front lines one day, and the Confederates became aware of his presence. Instead of trying to shoot him, the order went out: "Turn out the guard for the commanding general!" The rebels lined up and saluted Grant, who returned the favor.

Everybody knew the cordiality could not last. In fact, when Grant heard on 5 November that Longstreet had left with his troops, Grant wanted to attack Bragg immediately; Bragg was weakened for the moment, but if Longstreet managed to defeat Burnside quickly, those rebel troops would be back again soon enough, or might take off on an excursion to threaten Grant's supply lines. Furthermore, Grant knew that President Lincoln regarded the relief of east Tennessee Unionists as a very important matter, and if those loyal citizens were threatened, Grant would probably have to go to their aid. Better to knock the props out from under Longstreet's offensive by smashing Bragg.

Thomas had to tell Grant it simply wasn't possible. The men were now well-fed, but the horses needed to haul artillery had either been eaten or were weak, and replacements hadn't yet arrived. Grant tried to argue the matter, suggesting alternate plans for moving the artillery -- but Thomas was an artillery man by training and quickly demolished Grant's suggestions. Grant accepted that an immediate attack was out of the question. He sent messages to Sherman, which amounted to: HURRY UP. More specifically, they ordered Sherman to leave one division behind to continue work on rebuilding railroad lines in the region, and bring up the other four divisions as fast as possible to Chattanooga.

The rail work was delegated to a division under Brigadier General Grenville M. Dodge. Dodge was expert engineer, who Indian tribesmen watching him in the Far West had nicknamed "Level Eye", and he put his troops to work efficiently and effectively. He had a monstrous job. Grant wrote later: "The road from Nashville to Decatur passes over a broken country, cut up with innumerable streams, many of them of considerable width, and with valleys far below the road bed. All the bridges over these had been destroyed, and the rails taken up and twisted by the enemy. All bridges and culverts had been destroyed between Nashville and Decatur, and then to Stevenson."

Dodge and his men accomplished miracles. Over the next month and a half, they would rebuild 182 bridges, a similar number of culverts, and re-lay about 101 miles (163 kilometers) of track. Few of his troops had any previous experience in such work, but they did a remarkable job that laid the logistical foundation for future offensive actions into the South.

Sherman arrived in Bridgeport, Alabama, on 13 November, ahead of his men, to be greeted by a message from Grant telling Sherman to come to Chattanooga for discussions. Sherman got into the town by the Cracker Line the next evening. He was glad to see that Grant was off his crutches, but shocked at the difficult situation in the town. "Why General Grant, you are besieged!"

"It's too true," Grant replied -- but he had plans for fix that problem soon enough. Grant felt that Thomas' men were still demoralized by their defeat at Chickamauga Creek, and wanted Sherman's relatively fresh troops to lead the breakout assault. Grant felt that once Sherman's men began driving back the rebels, Thomas' men would recover their spirits and prove effective again. Hooker and his troops would lend a hand where it seemed necessary.

Sherman had to get his men to Chattanooga first. Longstreet had been gone for ten days and could be back at any time, so there was a need for haste. Sherman left to collect his troops the next afternoon, and hoped to have them there to begin the breakout on 20 November.

BACK_TO_TOP* Although Sherman left Chattanooga in a hurry on 14 November to collect his troops, haste was not possible due to rainy weather that only seemed to get worse, turning the roads into quagmires. Sherman wasn't in place with three of his divisions, ready for assault, until 23 November. The fourth division, under the command of Brigadier General Peter J. Osterhaus, was stranded when the rising Tennessee washed away a pontoon bridge. Grant shrugged, ordered Osterhaus to join Hooker's forces instead, and detached a division under Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis to join Sherman as a replacement. Sherman took the precaution of massing his troops across the Tennessee River in the hills to keep Bragg from realizing the scale of Union reinforcements. Grant hoped that the comings and goings of Union columns around Chattanooga would confuse Bragg. It worked.

The delay actually worked in Grant's favor, for on 22 November Bragg had decided to detach two more divisions to assist Longstreet, then besieging Burnside in Knoxville. By the time the Federal assault was ready to go forward on the morning of 24 November, the two rebel divisions were already moving out, making the odds in favor of the Yankees just that much better.

Bragg was betting that the strength of his position on the high ground would compensate for his inferiority in numbers, and he also believed, with some but not enough justification in fact, that Longstreet's move towards Knoxville would encourage the Federals to send troops off in that direction -- a belief that had been reinforced by the confusing movements of Sherman's forces. Bragg was trying to confuse the Federals in turn, sending Grant a note on 22 November: "As there may still be some combatants in Chattanooga, I deem it proper to notify you that prudence would dictate their early withdrawal." Grant, who had no high opinion of Confederate generals in general, and particularly had no high opinion of Braxton Bragg, saw the message as the joke it was.

Bragg knew that the Federals were building up reinforcements, writing to his wife that he found a strange beauty in the impressive terrain, "brilliantly lit up in the most gorgeous manner by the myriads of camp fires." The myriads of campfires meant myriads of Union troops. They wouldn't remain at their campfires for long. Grant had received reports from a rebel deserter that Bragg was pulling out. In this case, the deserter may have been confused by the two divisions that Bragg was sending to assist Longstreet. Although the report was incorrect, it left Grant eager to move.

At 12:30 on the afternoon of the 23rd, Thomas' men moved out in front of the town on what seemed to be a dress parade, marching with spit and polish and bands blaring until all of Thomas' men were in formation. Confederate pickets got out of their entrenchments to watch the festivities -- but at 1:30 PM, Federal buglers and drummers called a "charge" and the Yankees swept forward abruptly, overrunning the advance line of rebel entrenchments around a small hill named Orchard Knob. The Federals quickly altered the entrenchments to face the other way. Grant was pleased that the Army of the Cumberland was by no means as cowed as he had assumed. Bragg was still not particularly worried, since he felt that even the relatively thin force on top of Missionary Ridge held such an advantage due to the terrain that the Federals had no hope of dislodging them.

The next morning, 24 November, Bragg received news that the Federals were pouring across the Tennessee River upstream of Chattanooga, poised to flank the weakly-defended northern end of the rebel line of Missionary Ridge. The force was Sherman and his men. Bragg was shocked by the news; although he knew that Sherman had been on the march towards the area, Bragg had assumed that Sherman was taking his divisions into the mountains to help Burnside. Bragg sent frantic orders to the tough General Cleburne, in command of one the divisions sent to reinforce Longstreet, to return the division on a double-time and block Sherman's force.

* The Confederates held the high ground in an arc halfway around the town, with Missionary Ridge dominating the northern segment of the rebel line and Lookout Mountain looking over the other. Missionary Ridge was very steep, with the rebels well dug in and supported by artillery.

Grant's plan specified that Hooker move his men against Lookout Mountain, while Thomas demonstrated towards Missionary Ridge to keep the rebels in place and Sherman administered a knockout flanking blow from the north end of Missionary Ridge. Hooker had three divisions -- consisting of one of those that he had brought from back East, one provided by Thomas, and Sherman's division under Osterhaus that had arrived late. Thomas had four divisions, while Sherman had four divisions as well, including three he had marched to the area and another provided by Thomas. Howard commanded two more divisions as a reserve.

Things went well, if not as planned. Sherman's troops had rowed across the river in the darkness the night before, capturing the sentries without firing a shot. By noon the next day, his engineers had set up a long pontoon bridge across the swollen Tennessee. Sherman moved his men onto high ground against light opposition, thinking that he was now poised to roll up Bragg's defenses. That afternoon, however, Sherman found out that his maps were faulty. He was on Tunnel Hill, named for the railroad tunnel that ran under it, and this hill was detached from Missionary Ridge by a rocky narrow valley. He would not be able to begin his proper assault for another day, and he had lost the advantage of surprise.

Hooker's attack on Lookout Mountain proved easier than expected. His primary goal was not to seize the mountain as such, but to clear the rebels off its slopes; seize the Chattanooga Valley, which lay between Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge and contained Chickamauga Creek; and then capture Rossville Gap, which cut through Missionary Ridge and gave the Federals a back-door route into Bragg's positions on the ridge.

There were only three rebel brigades on Missionary Ridge to hold back three divisions of Yankees. The rebel defense was disjointed and confused, while the Union attack went like clockwork. The Confederates were ordered to perform a fighting withdrawal, and they did so against fast-moving lines of Federals moving up the mountain in mists and intermittent drizzle. The rebels inflicted casualties on the attackers and then fell back. By sundown, Hooker's men were in possession of the western side of the mountain.

* Grant was not entirely satisfied with operations on 24 November, and hoped to deal with the rebels decisively the next day. That night, there was an eclipse of the moon. Both sides took this for a portent: the Confederates felt it meant bad luck for them, and the Federals agreed.

The last rebel defenders of Lookout Mountain pulled off of the eastern side of the peak during the night to brace up the defense of Missionary Ridge, damaging the bridge over Chickamauga Creek to block pursuit. Union soldiers crawled up the cliffs of the tall mountain during the night and planted the Stars & Stripes on top just before dawn. When the sun came up, the banner was waving on top for all to see. The fight for Lookout Mountain had cost the Federals about 480 men while the rebels had lost about 1,251, most taken prisoner. The newspapers played up the "Battle Above The Clouds" and the men who did it, though Grant later pointedly wrote that it was all a myth, nothing more than a large-scale, one-sided skirmish. That was uncharitable, but few Union generals felt charitable towards Joe Hooker.

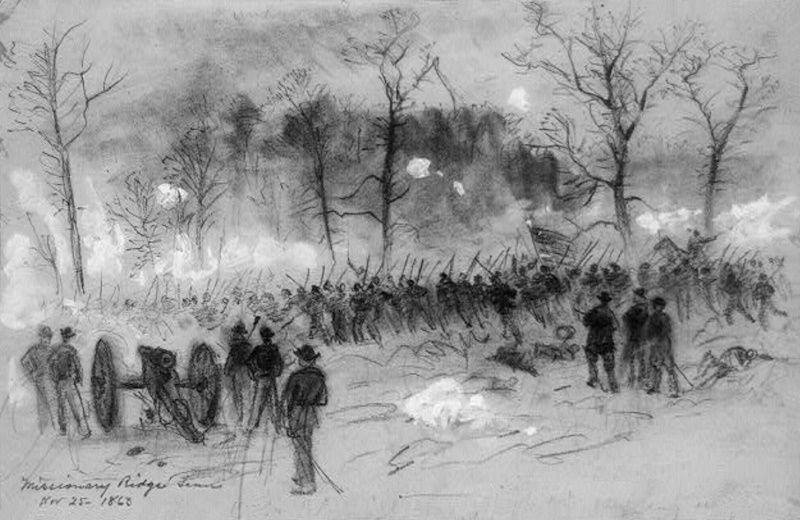

* Sherman's attack on the north end of Missionary Ridge from Tunnel Hill on 25 November 1863 began about 10:00 AM -- and went nowhere, even though Howard's two reserve divisions were added to the weight of the four Sherman already had on the spot. The broken terrain was an obstacle to a coordinated attack, and Pat Cleburne's men held the rocky and steep slopes of the far side of the gulch. The rebels threw back attack after attack, inflicting serious casualties on the Federals, who literally rolled back down the hillside. The Federals were unable to inflict any serious harm on the defenders. Cleburne described the fire his men sent into one Union advance as "a continuous sheet of hissing, flying lead."

At about 2:00 PM, Thomas was ordered to detach a division to help Sherman, but Sherman had replied that there was really no place to squeeze them into his narrow front; the division was quickly turned around and put back in place. At 3:00 PM, the Confederates, sensing that Sherman's troops were exhausted, hit them with a countercharge that completely took the wind out of them.

Sherman decided he'd had enough, and sent a message to Grant at his headquarters on Orchard Knob, saying that further efforts were futile. Grant had not had enough, and sent back a simple order: "Attack again." Sherman sensibly followed the letter of his instructions, sending in only about 200 troops from Brigadier General Joseph Lightburn's brigade. They were, as Sherman expected, badly cut up and sent falling back. Sherman lit a cigar, took a few drags on it, and then said to an aide: "Tell Lightburn to entrench and go into position." Sherman cared for his men; he had sacrificed as many of them as his orders had required him to, and he was unwilling to sacrifice any more.

* By that time, Hooker was across the Chattanooga Valley and pounding at Rossville Gap. He would have been there hours earlier, but his men had halted for about three hours while the bridge over Chickamauga Creek was repaired. Once they got across the creek, they quickly moved on the rebel defenders in Rossville Gap from several directions, smashing the Confederates there and putting Bragg's entire defense at risk. Grant had little confidence in Hooker and no great confidence in the two corps he had been given from the Army of the Potomac, which he regarded with some basis in fact as cast-offs. However, both Hooker and his men were proving much more effective than Grant had expected.

The real surprise was in the center of the attack, in front of Missionary Ridge. Sherman had been telling Grant that the Confederates facing Tunnel Hill were being continuously reinforced, though that wasn't true; in mid-afternoon PM Grant noticed a movement on the top of Missionary Ridge that he interpreted as yet another transfer of reinforcements to block Sherman. He ordered Thomas to make a "demonstration" in front of Missionary Ridge to keep the rebels occupied.

Thomas had been doing little all day and was restless. He had a personal reason to want to be more involved with the battle, having a score to settle with Braxton Bragg. Some time earlier, Thomas had received a letter from a Northerner to a rebel officer, and had tried to pass it through the lines with a covering note so it could reach its proper recipient. Bragg immediately replied by sending back the message with a note of his own: "Respectfully returned to General Thomas. General Bragg declines to have any intercourse with a man who has betrayed his State." It was Bragg at his pettiest; Bragg had once been Thomas' commanding officer and it hit a nerve in the normally unflappable Thomas: "Damn him! I'll be even with him yet!"

A simple demonstration wasn't adequate revenge, but it would have to do. The order went to Gordon Granger, directing the corps remaining under Thomas' control, to move forward with his four divisions, 25,000 men in all, and take the Confederate rifle pits at the base of Missionary Ridge.

Thomas waited and nothing happened. It turned out that Granger had been distracted by conducting a personal artillery duel with some rebel guns on Missionary Ridge, and hadn't got around to ordering the attack. Thomas and Grant found him and confronted him. Thomas said: "Pay more attention to your corps, sir!" Grant added: "If you will leave that battery to its captain and take command of your corps, it will be better for all of us." Granger took the hint, and at 3:40 PM, six guns were fired in succession to begin the assault.

The attackers faced a triple line of rebel entrenchments, including the rifle pits at the bottom of Missionary Ridge, one halfway up its slope, and one at its top. Bragg had about 112 guns on top of the ridge. As the line of Federals advanced, the Confederate guns all went off. Although the Confederate fire was deadly, it had a perverse effect on the Federals: instead of intimidating them, they stepped up the pace, with some breaking into a run, and many shouting: "CHICKAMAUGA! CHICKAMAUGA!" They were rested and equipped, and had scores to settle of their own -- not only with the rebels who had bloodied them at Chickamauga Creek, but at the Union reinforcements who had gallingly come to "rescue" them.

The Federals quickly overran the Confederate line of entrenchments at the base of Missionary Ridge, with a few rebels scrambling up the steep slope but most, unnerved by the determined charge of the Yankees, simply throwing down their weapons and giving up. Once the Union men got to those trenches, they found themselves exposed to fire from above, and in sheer annoyance some of the troops decided to keep right on going. As they moved out, the others began to pick up the idea, and suddenly the entire wave of four Federal divisions was charging straight up the ridge, even as their officers called out for them to stop. They were ignored. Faced with the prospect of being left behind by their own men, the officers gave it up and joined the charge.

It seemed suicidal. One rebel officer concluded that all the Federals were drunk. Grant was watching from the rear with Thomas. Grant was chewing on a cigar, pulled it out of his mouth, and said, and demanded: "Thomas, who ordered those men up the ridge?!"

Thomas replied casually: "I don't know. I did not." Gordon Granger was there, and Grant then barked at him: "Did you order them up, Granger?!" Granger replied: "No, they started up without orders. When those fellows get started, all Hell can't stop 'em!" Grant did not share Granger's enthusiasm, since the Confederate position seemed impregnable and the men were sure to be slaughtered. He considered calling the men back, but decided against it, muttering: "It's all right if it turns out all right. If not, someone will suffer." Thomas, not easily troubled, simply watched the rush up the slope.

The men scrambled upwards, moving as fast as they could with their packs, rifles, and heavy overcoats, getting on their hands and knees when they had to, or jabbing bayonets into the slope to pull themselves up. They were taking casualties but kept right on coming. The rebels found it unnerving.

Bragg, in his usual sour way, would later say that Missionary Ridge should have been held by a skirmish line. In fact, the Confederates had been overconfident of the strength of their position on Missionary Ridge, and had done a poor job of setting up their defenses. The troops at the entrenchments at the bottom of the ridge had been supposed to fire a few volleys and then retire up the hill to more defensible positions, but that had not been made clear to them; between the capture of most of them and the terrified flight of the others, they helped panic their colleagues up the ridge. Worse, the top line of defenses on the ridge had been laid out on the very ridgeline, without regard to fields of fire. For much of the charge up the ridge the Confederates were either not able to get the Yankees in their sights, or were in the position of firing through their own people.

The Confederates on top of the ridge had a full view of the mad rush of 25,000 Federals up the hillside, and it was too much for them. Nothing that had happened to the Confederate Army of the Tennessee had done much to give them morale; they broke and ran, ignoring their officers, including Braxton Bragg, who ordered and threatened and pleaded with them to stand their ground. Bragg himself eventually decided to flee, narrowly evading capture. When the Federals got to the top of the ridge, all they encountered was the sight of a panicked rush of Confederates down the far slope. A winded Indiana private said: "My God, come see 'em run!"

Major General Montgomery C. Meigs, who as the Army quartermaster-general had come out from Washington to help deal with supply issues, had been standing with Grant on Orchard Knob, but suddenly one Union major spotted Meigs among the troops pouring over the top of the ridge, with the general "wild with excitement, trying himself to wheel one of those guns on the rebels flying down the opposite side of the mountain, and furious because he couldn't find a lanyard with which to fire the gun."

A Kansas private reported: "Gray-clad men rushed wildly down the hill and into the woods, tossing away knapsacks, muskets, and blankets as they ran. Batteries galloped back along the narrow, winding roads with reckless speed, and officers, frantic with rage, rushed from one panic-stricken group to another, shouting and cursing as they strove to check the headlong flight. In ten minutes, all that remained of the defiant rebel army that had so long besieged Chattanooga was captured guns, disarmed prisoners, moaning wounded, ghastly dead, and scattered, demoralized fugitives. Mission Ridge was ours." Years later, a Confederate soldier told a Union officer: "You Yanks had got too far into our innards."

The winners were jubilant, "completely and frantically drunk with excitement", waving flags and cheering loudly. Phil Sheridan was sitting straddled on a captured gun and cheering, though another officer who jumped on a gun didn't bother to check to see if it was hot first, and could barely sit down again for two weeks. Gordon Granger, who had galloped off to join his victorious troops as they dashed up the slope, rode around excitedly, laughing and roaring: "I'M GOING TO HAVE YOU ALL COURT-MARTIALED!" Their humiliation at Chickamauga Creek had been avenged, and they had shown up the newcomers who had been supposed to carry the battle.

With Missionary Ridge gone, the rebel siege of Chattanooga was broken for good. Bragg managed to collect his forces and withdraw in reasonable order, with the two divisions under Pat Cleburne and Alexander Stewart performing a stubborn rearguard action that allowed the Army of the Tennessee to get off the battlefield in good order. It was late in the day and late in the year, and the early fall of darkness allowed the Confederates to make their escape without immediate pursuit by the Federals.

* The Yankees took up the pursuit the next morning, 26 November. They overran the Confederate railhead at Chattanooga Station, finding the rebels gone, with supplies burning in the streets and discarded equipment lying everywhere. On 27 November Cleburne's men set up am ambush at Ringgold Gap, a very narrow mountain pass about 15 miles (24 kilometers) south of Chattanooga, inflicting almost 450 casualties on a force of 12,000 under Joe Hooker and losing less than half that many themselves. The fight allowed Bragg to regroup in Dalton, Georgia, which was defensible for the moment.

Bragg of course blamed the defeat on the "shameful conduct of the troops". Yankee soldiers who collected rebel prisoners and dead after the battle were more sympathetic, observing how ragged, starved, and ill the enemy was. The Confederates had lost only about half the number of men killed and wounded as the Federals, but the Yankees had hauled in over 4,000 rebel prisoners -- with Confederate losses were tallied at about 5,700, compared to a total of about 5,800 for the Federals. A good percentage of the Union casualties were taken in the mad dash up Missionary Ridge, which though a military miracle had been by no means bloodless.

As Civil War battles went, these were moderate losses, nothing to compare to Antietam, Gettysburg, or Chickamauga Creek -- but the victory had outsized strategic implications. The rebels would never drive the Yankees out of Chattanooga, while the Federals were now poised to jump into the heart of the Confederacy. A Northern reporter described Chattanooga as now "a gateway torn asunder." The Confederate victory at Chickamauga Creek had encouraged Southerners, but end it had come to nothing. A demoralized Confederate lieutenant told his company commander: "This is the death knell of the Confederacy."

The fight on Missionary Ridge gave the Union new heroes as well. Seven Congressional Medals of Honor, the highest American military decoration, were awarded to men who had participated. One was a teen-aged first lieutenant named Arthur MacArthur JR of the 24th Wisconsin, who carried the regimental colors to the top of the ridge after three other color-bearers had been killed. Decades later, MacArthur became the US Army commander of American forces in the occupation of the Philippines. His heroism would inspire his son, Douglas MacArthur, who became one of America's most prominent generals of World War II.

* At first Grant had sulked while Thomas' men cheered on top of Missionary Ridge, since the actual conduct of the battle had completely stood his plans on their head. Grant said, using extremely hot language by his standards: "Damn the battle! I had nothing to do with it!" However, Grant was too much of a pragmatist to stay unhappy for what amounted to a massive victory.

The day after the bloody reverse at Ringgold, Grant abandoned the pursuit of Bragg's army. It was way too late in the year to move a full Union army through rough terrain, and the War Department was nagging Grant to do something to help Burnside in Knoxville. Offensive operations into Georgia would have to wait until spring.

BACK_TO_TOP* Out West in Tennessee, the permanent loss of Chattanooga cut the supports out from under Longstreet's siege of Knoxvillec -- but even when Longstreet got the news, he didn't give up right away. That was not just obstinacy: he felt he had a better chance of escaping with his troops across the mountains into Virginia if he dealt with Burnside beforehand, and if Longstreet left without dealing Burnside a blow, Burnside would join Grant and destroy Bragg's Army of the Tennessee once and for all. Longstreet told one of his officers: "There is neither safety nor honor in any other course than the one I have chosen and ordered."

Such thinking required nerve, all the more so because Longstreet knew perfectly well that he was way out on a limb. With Bragg's force knocked off the playing board for the moment, the Federals could now concentrate their attention on Longstreet -- which was exactly what they were doing. Lincoln's congratulations to Grant had been short and to the point:

WELL DONE. MANY THANKS TO ALL. REMEMBER BURNSIDE.

On 27 November, Grant ordered that Granger's reserve corps to be sent to Knoxville. However, when Grant returned to Chattanooga on 29 November after chasing Bragg down into the Georgia hills, he found Granger and his men still sitting in Chattanooga; Granger, who seems to have had erratic ideas about how things were done in an army, had decided that the order was a bad idea and simply hadn't complied. Grant gave Granger's reserve corps to Sherman and ordered Sherman to relieve Burnside. Granger ended up being transferred to the Department of the Gulf.

Sherman was by no means happy with the assignment either. The Unionists in the hill country might have been dear to President Lincoln, but they were not to Sherman. Detesting politics on principle, political rationales made no sense to him; Sherman was baffled why anyone wanted to fight for such a wild, poor, and worthless region. Sherman wrote Grant: "That any military man should send a force into East Tennessee puzzles me."

* As it turned out, Sherman's move into the region would be a waste of time by anyone's assessment. After many delays, Longstreet ordered an attack on Burnside's defenses around Knoxville for the morning of 29 November -- focusing on a set of earthworks named Fort Sanders, named after the cavalry commander who had protected Burnside's escape into Knoxville.

Fort Sanders was formidable, but it was near a creekbed that could provide cover for an assault. Longstreet hoped to achieve surprise and so he planned for a daybreak assault without artillery preparation -- but showed his hand by seizing rifle pits in front of Fort Sanders the evening before, wanting to place sharpshooters in the pits to suppress the defenders. Unfortunately, the only result was that he completely lost the element of surprise.

The rebels were ordered to charge fast without firing and take Fort Sanders by bayonet. The Federals were waiting for them. The rebels dashed forward in the early light into a storm of bullets and canister shot. They did not notice strands of telegraph wire that the Yankees had wound around trees and stumps and stakes in front of their defenses. The dash towards the Federal entrenchments was broken as rebel troops in the lead were thrown on their faces by the wire. They got up again, swearing furiously, to run into more of the same while Union troops poured fire into them.

The defenders were mostly Scotsmen of the 79th New York Highlanders regiment. The rebels managed to make it to a ditch in front of the walls of Fort Sanders. The ditch had been assessed by Longstreet as about 5 feet (1.5 meters) deep, but which turned out to be about 9 feet (2.75 meters) deep. Longstreet, observing the ditch earlier with binoculars, had seen a man walking across it with his head and shoulder above the ditch. Longstreet failed to realize that the man had been walking on a plank set across the ditch.

The attackers had not thought to bring scaling ladders, and the far side of the ditch was muddy and icy. They went into the ditch to find themselves penned in, to be slaughtered by volleys of Yankee musketry and blasts of canister. Lieutenant Samuel L. Benjamin, the artillery commander in Fort Sanders, ordered his men to take 50 cannon shells and set them with 3-second fuzes; the shells were lit and thrown into the ditch, with devastating effect. Benjamin commented grimly: "It stilled them down." Some rebels managed to scale up the far side of the ditch, only to have the Scotsmen simply snatch them, haul them roughly over the top, and take them prisoner. One rebel officer was hauled away demanding that the Federals surrender while the Scotsmen laughed at him.

Longstreet was coming up with the second assault wave, and saw his plan was a complete bust. He ordered the recall sounded immediately, even though the brigadiers with him wanted to give it a try themselves. The Confederates floundering in the ditch pulled out, leaving behind dead, wounded, and those who'd had enough and surrendered. One rebel private of Irish persuasion, now a captive of the Yankees, saw some humor in the situation. He casually lit up his pipe and told his comrades: "Bedad, boys, General Longstreet said we would be in Knoxville for breakfast this morning, and so some of us are."

Burnside and Longstreet had been friends before the war. Given Burnside's decent nature, it was little surprise that a Yankee courier, under a flag of truce, soon came to Longstreet, relaying General Burnside's respects, offering Longstreet the opportunity to retrieve his dead and wounded; Longstreet didn't even have to ask. He gratefully accepted, and in fact he had to request an extension, there being an excess of dead and wounded on the field. The assault had cost him 813 casualties, about half of them taken prisoner. The one-sided fight had cost Burnside 13 men.

* That seemed like an entirely final settlement of the issue, but the same day Longstreet received an order from Bragg that pounded one more nail in the coffin of his excursion into East Tennessee. The order specified that Wheeler take his cavalry and rejoin the survivors of the Confederate Army of the Tennessee in Dalton, Georgia, and that Longstreet march his men to Dalton as well.

Wheeler left immediately, but was uncertain that moving towards Dalton was safe. Once again he demonstrated good sense, since he quickly learned that Sherman was on the march with six divisions and would certainly tear him to pieces. Longstreet decided to disobey the order. Beginning on the evening of 3 December, he pulled out from Knoxville, marching northeast in the direction of Virginia. He halted his force in Rogersville for the winter.

Sherman's cavalry arrived at Knoxville to find they were not needed. Sherman followed with his troops, and Burnside treated Sherman to a fine turkey dinner in a local home. Burnside suggested to Sherman that reports of the distress of the defenders of Knoxville had been exaggerated; Sherman was disgusted.

Grant wanted Burnside and Sherman to hunt down Longstreet, but much to Grant's annoyance, they didn't pursue. There was good cause for this, since the terrain was rugged, winter was setting in, and Longstreet was good at setting traps. Sherman wanted no more part of campaigning for a barren wilderness anyway. The real action in the West was now in the direction of Atlanta. Grant shrugged and dropped the matter. Sherman detached two of his divisions to help hold down East Tennessee, and marched the other four back to Chattanooga.

Longstreet's misadventures in the West were all but over. There would be complaints about his failures, but Longstreet had done what he could under impossible conditions. There was nothing in it all to give him much satisfaction, but at least he had washed his hands of Braxton Bragg. As far as Bragg himself went, he would soon find himself on the shelf.

BACK_TO_TOP* This document was derived from a history of the American Civil War that was originally released online in 2003, and updated to 2019. It was a very large document, and I first tried to simply break it into volumes for publication in ebook format; however, that proved unsatisfactory, and I decided to break it into separate focused volumes. This stand-alone document was initially released in 2025.

* Sources:

When I was interested in picky details, I'd scrounge the internet, particularly the Wikipedia, for leads.

* Illustrations credits:

Finally, I need to thank readers for their interest in my work, and welcome any useful feedback.

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 aug 25BACK_TO_TOP