* The failure of American efforts against Canada in 1814 left the Madison Administration at a loss, unable to gain an advantage in the war while the ability of the government to fund the conflict continued to evaporate. British assaults on American coastal communities ramped up, ultimately leading to a raid on Washington DC in which the government was driven out in humiliation and government facilities burned. In Ghent the British, understanding the strength of their bargaining position, pressed their American counterparts across the negotiating table for painful concessions.

However, the British then suffered stinging reverses at Baltimore and on Lake Champlain; coupled with the depredations of American raiders on British shipping and the choking off of British commerce due to war, the Americans began to see that they might well be able to at least hold their own in a peace settlement.

* While the fighting sputtered on in America, across the Atlantic that August the American peace commissioners were sitting down at the table with their British counterparts in Ghent. The American team was first-class, most notably with the smooth, shrewd, and diplomatic Gallatin more or less at the head, though Adams and Clay were substantial enough as well. Adams and Clay were bound to clash, however, Adams being prim and pious, while Clay enjoyed his liquor and all-night sessions at the card tables -- it was almost a replay of the relationship between John Adams, John Quincy's father, and Benjamin Franklin in American diplomacy with France a generation before. Gallatin proved able to keep them more or less working together by knowing when to say something and when to keep quiet, and such disputes as arose among the negotiators were never much more than quibbling. As Adams put it: "Upon almost all of the important questions, we have been unanimous."

The British team was not their equal, most of Britain's best diplomats being off at the Congress of Vienna, trying to sort out the tangles of the emerging post-Napoleanic Europe. The British were represented by Henry Goulburn, an undersecretary in the Colonial Office; William Adams, an Admiralty lawyer; and Lord James Gambier, a Royal Navy admiral. The British came to the negotiating table in a confident mood, with Adams irritably describing their attitude as "arrogant, overbearing, and offensive." However, the British representatives overplayed their hand, their proposals being properly rejected as outrageous; they quickly found themselves on a leash, unable to make any serious offers without consulting with London -- a process that helped drag out the negotiations, though the British found delay all to the good, allowing the Americans to squirm.

The British position was stern, calling for restrictions of American fishing in Canadian waters; territorial concessions and demilitarization along the northern border to improve Canadian security; and most significantly, an Indian buffer state hemming in the US Northwest. Such a buffer state would keep faith with Britain's Indian allies and, not at all incidentally, place a limit on American expansion to the West. Although the Americans had hoped to press demands of their own, particularly an end to impressment, thanks to America's weak military position, they could hope to get no more than maintain the status quo ante bellum.

* The British negotiators had good reason to feel they held the strong hand. Ever since the fall of Napoleon, the British had been hauling veteran troops across the Atlantic to aid in the fight against the Americans. From the spring to the summer the total number of British soldiers in the theater had almost doubled, to 30,000 men; by the end of the year, the total would reach 40,000. Ironically, with so many able-bodied Canadians called up into the military, there was no way Canada could possibly feed such a large force -- and in reality it was kept provisioned by a cross-border trade with the Americans that had become so heavy in volume that calling it "smuggling" was almost comical, there being nothing particularly covert about it.

As noted, the trade had been going on since the start of the conflict, but now it was becoming even more profitable. Federalist New Englanders, who never wanted the fight in the first place, had no problems with commerce with the enemy; even the authorities were involved, and those few outsiders who tried to obstruct the trade often found themselves targets of harassment by local officials. The one good thing in the trade for the government in Washington was that American suppliers could and did charge a premium for their products, increasing the drain of the war on the British treasury.

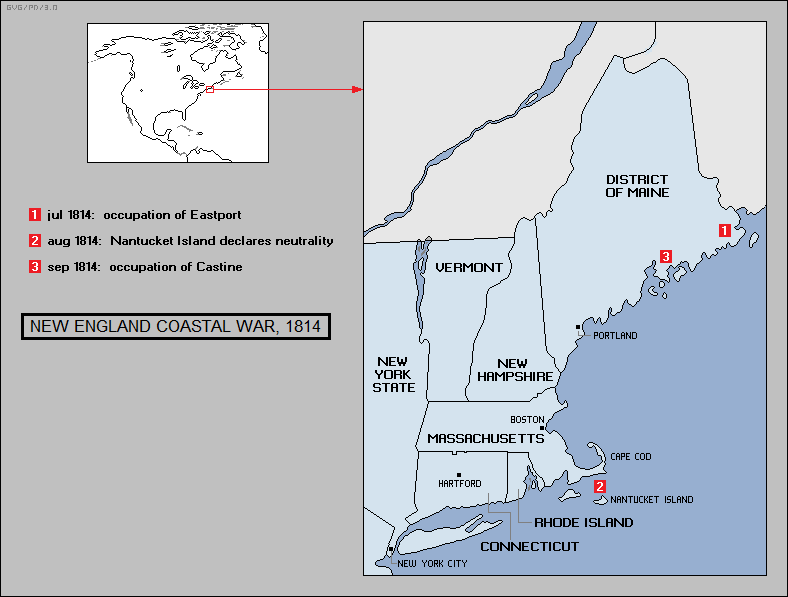

Of course, the provisions allowed the enemy to raise more hell, with the British expanding their coastal operations, the prime targets being Maine and, as earlier, the Chesapeake Bay area. In mid-July 1814, British forces occupied Eastport in Maine, following that action up with the occupation of Castine in September, encountering no real opposition in either case. The light frigate ADAMS was burned on 3 September to prevent its capture by the British.

In any case, the occupation was no great trouble to the inhabitants, who had little liking for the war, were given a loose leash by the occupation authorities, and did a good business supplying them. Indeed, there were reports of locals expressing joy at the humiliation of the government in Washington by the invasion and welcoming the British enthusiastically. The government in turn cut off mail service to the occupied region and talked with regional authorities about a campaign to retake the area, but nothing was ever done.

The British struck at other ports on the New England coast, sometimes inflicting substantial damage, though in a few cases getting the worst of it. There was no seriously challenging Royal Navy might, however, with some coastal towns paying "protection money" to the British to buy safety. The Massachusetts island of Nantucket, isolated by Royal Navy blockaders and confronted with starvation, was persuaded by the British to simply declare neutrality in August, the authorities there releasing British prisoners from the local prison and cutting off dealings with the Federal government. It was a sensible deal from the point of view of the British, since otherwise they would have had to occupy the island and take responsibility for keeping the people fed. As with the occupation of Maine, there were many Americans who had no great problem with the blockade, going out to Royal Navy vessels to sell produce or other goods, and being handsomely paid in hard currency.

BACK_TO_TOP* Matters were less polite in Chesapeake Bay. Admiral Warren's conduct of the naval war hadn't made his superiors back home very happy; Warren spent too much too complaining about lack of resources, and though his superiors recognized he had valid complaints, that was still not the stuff a Royal Navy officer was supposed to be made of. He had been relieved of command in November 1813, to be replaced in early April by Admiral Alexander Cochrane, a Scotsman. Cochrane, now with a more substantial force of raiders under General Robert Ross of the Royal Marines, a veteran of the fighting in Spain, began to escalate attacks in the region.

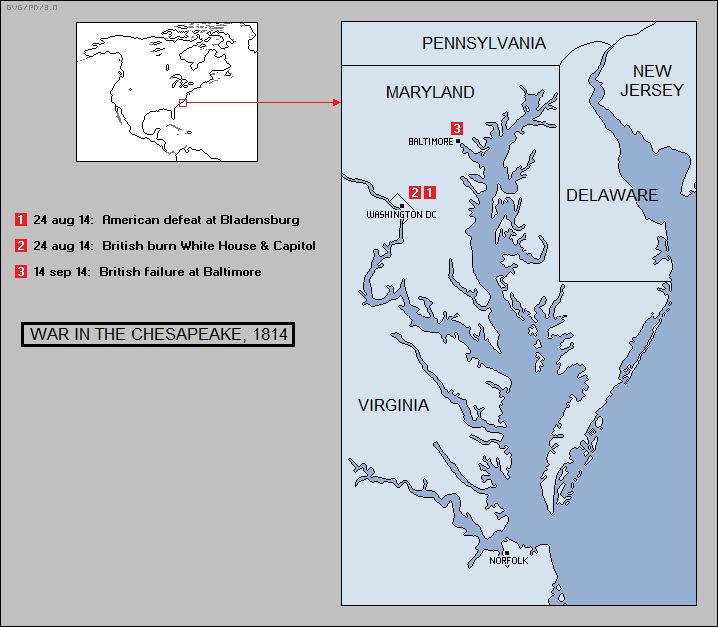

After conducting scattered coastal raids to keep the Americans off-balance, the British moved on Washington, initially in a series of raids up the Patuxent River, which ran north of the Potomac and terminated near the city. There were running skirmishes through June between British vessels and a small flotilla of gunboats and gun barges under the command of Commodore Joshua Barney, a Revolutionary War hero and an accomplished privateer. Barney was unable to do more than harass the invaders, finally being forced to torch his vessels and put his sailors on the march to Washington.

There was some hope that the British would be satisfied with the destruction of Barney's annoying "mosquito fleet", but they were feeling ambitious. On 19 August 1814, a force of some 4,000 British troops under Cockburn and Ross departed from landings on the Patuxent River and marched on Washington. Although the vulnerability of Washington had long been apparent, War Secretary Armstrong had never taken the possibility of a British attack on it very seriously: Washington was really just a small town, of no real consequence except for the fact that the government resided there -- and if it were attacked, the government would simply go someplace else. Baltimore seemed like a much more significant target, not just because of its greater extent and affluence, but because it was the biggest host port for privateers.

As a result, resources were not available to defend Washington when the British did decide to move on the town. Local militia were brought in, being placed under the command of General William Winder and marched about in a confused manner in the August sun. The summer heat, made all the more insufferable by the region's notorious suffocating humidity, drained the men; through lack of sleep and a failure of the leadership to keep them properly fed, they were reduced to exhaustion.

At the Battle of Bladensburg on 24 August, Ross dispersed a motley force of about 5,000 weary militia, Commodore Barney's Navy men, and others pressed into the battle line -- the defeated troops departing the battlefield in such disorder that the event became known as the "Bladensburg races". Barney was wounded and captured. Ironically, the American troops inflicted well more casualties on the invaders than they suffered themselves, suggesting that if the defenders had been more disciplined and better led, the British incursion might well have been a disastrous failure.

Ross then entered Washington, occupying the government buildings. The president had already left, with his wife Dolley managing to save some of the valuables in the White House -- but she left in such haste that when British troops entered the building, they found dinner set. They ate and drank their fill, took some loot, and then torched the structure. The Capitol building, which at the time contained the Library of Congress, and other government installations were also burned.

The British were conscientious enough to avoid damage to residential areas. Dr. William Thornton, a British-born Federalist and superintendent of patents, managed to save the Patent Office by convincing the British that it would be a crime to destroy the knowledge it contained. When the invaders set upon the offices of the Republican newspaper THE NATIONAL INTELLIGENCER, which had been heaping abuse on Cockburn in its pages, neighbors managed to talk the troops out of burning it, since it would have taken the neighborhood with it. Cockburn satisfied himself by personally supervising the enthusiastic smashing up of the building by his men. The editors of the paper actually complimented Cockburn on his restraint once they began printing again, pointing out that such looting of civilian housing as took place had been performed mostly by locals.

The Americans torched the Navy Yard themselves before they pulled out, destroying the unfinished warships COLUMBIA and ARGUS in the process. Thanks to the combined incendiary efforts of the two sides, a British officer reported the "sky was brilliantly illuminated by the different conflagrations." There were thunderous summer storms the next day, 25 August, which blew down several structures and injured or killed a number of British troops. There was also an incident that day in which a dry well that was being used as a powder magazine blew up in a tremendous explosion that scattered British soldiers, whole or in pieces, over the landscape. The invaders left the city that day, finally withdrawing on their ships five days later.

In the meantime, a Royal Navy force under Captain James Gordon had been working its way up the Potomac to support the raiders. The British flotilla ran late, not reaching Fort Washington, just downstream of the city, until 27 August, after the invaders had left. The fort presented no obstacle to Gordon's ships since it had been hastily abandoned, with the British then docking at Alexandria. Gordon seized all the public stores he could get his hands on, as well as 21 merchantmen loaded with cargo, and then departed. American forces made things hot for him as he went downstream, but he made his escape with his ships and loot generally intact.

* Madison returned to Washington that day. While he was the target of abuse and jeers, most of the blame was conveniently laid on War Secretary Armstrong. Armstrong was forced to resign, with Secretary of State Monroe putting on a second hat as war secretary. The burning of Washington caused particular resentment among Americans against Britain; it was also denounced by some opposition MPs and newspapers in Britain. The STATESMAN of London protested: "The Cossacks spared Paris, but we spared not the capitol of America." Britons were more generally pleased with the action, seeing it as exactly what should have been done to the upstart Americans, and only just considering American depredations against Canadian towns. General Ross was officially commended -- though by that time, he wasn't in a condition to appreciate it.

BACK_TO_TOP* The next target of the British was Baltimore. The city had been preparing for an attack since the previous year, and had a substantial force of relatively well-drilled militia. The land approach was covered by several lines of defenses; the harbor was guarded by Fort McHenry, and blocked by a line of sunken gunboats. General Winder attempted to take command of local forces, but the authorities wisely refused to pay any attention to him, instead preferring to direct the fight themselves.

General Ross landed a force of about 4,500 men at North Point near the city in the dark hours of the morning of 12 September. A few hours later, after sunrise, the British collided with a force of 3,200 militia under General John Stricker; the defenders were finally pushed back, but they managed to inflict more casualties on the British than they suffered themselves. The most significant British casualty was General Ross, picked off by an American rifleman in the last moments of the battle. Ross was very popular among his troops, and his death did much to dispirit them.

Colonel Arthur Brooke took command and the next day brought his men up to the approaches of the city's defenses. Lacking naval support and finding the defenses stout in appearance, Brooke decided not to push his luck; with no other sensible course of action available, he withdrew in the dark hours of the next morning, much to the celebration of the defenders.

Royal Navy warships would not be in a position to support an attack on the city's defenses unless they could neutralize Fort McHenry, which would allow small warships to move in close. From 13 September into 14 September, Cochrane's warships pounded the fort with a bombardment of 1,500 shells and rockets, but the fort was sturdy and little damaged; only four Americans were killed, plus two dozen injured. Cochrane then tried to send in a force in small boats under the cover of darkness to neutralize the city's defenses. It didn't work; the boats were detected, and the Americans fired on them. The shooting was wildly inaccurate in the darkness and the British were not heavily injured, but they had lost the element of surprise. Come the sunrise, the shots were likely to be well more effective, and so the intruders went back to their ships.

Lacking any other ideas, the British cut their losses and left, with the fleet sailing to the Caribbean, where new opportunities presented themselves. The Americans played up the victory, feeling it avenged their humiliation at Washington.

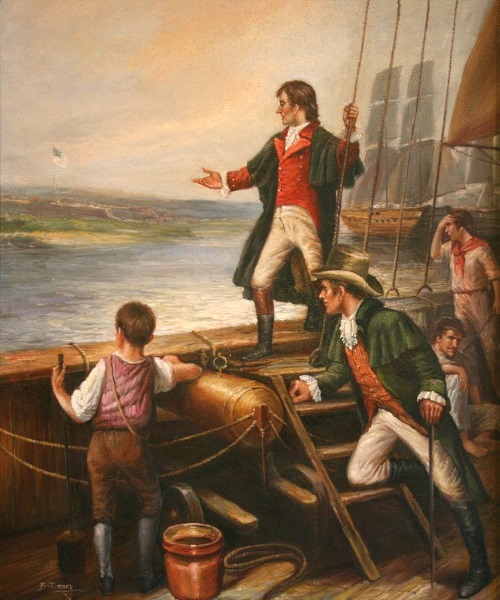

The battle would certainly create the most lasting memento of the war, in the form of the American national anthem. During the incursion, a Federalist named Francis Scott Key went to a British ship to negotiate the release of a prisoner; since the British feared he would report back on their activities, they detained him until they departed. Key witnessed the bombardment of Fort McHenry from the deck of a British warship, being inspired by the scene to write new patriotic lyrics for a popular drinking song of British origins that had already been given several other sets of lyrics:

Oh! Say, can you see by the dawn?s early light, What so proudly we hailed at the twilight?s last gleaming, Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight, O?er the ramparts we watched, were so gallantly streaming? And the rockets? red glare, the bombs bursting in air, Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there. Oh! Say does that star-spangled banner yet wave, O?er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

The "Star-Spangled Banner", as Key named it, was rousing and became popular, even though the range of the song from low pitch to high made it difficult to sing; in 1931, it would become America's official national anthem.

BACK_TO_TOP* Despite the good news from Baltimore, for the moment the situation seemed dark. The government was effectively bankrupt, with no tax revenues and no big lenders available to provide temporary funds; the only thing left was to issue Treasury notes and sell war bonds -- and they were going at an ever steeper discount. Not only was it impossible to recruit more troops, it was difficult to hang on to the troops already in the ranks, and desertions were on the rise. Who could blame them? They weren't being paid or fed or clothed, and the camps tended to be pestholes where disease cut lethally through the ranks. The soldiers had every reason to leave, and often the only way to keep them in service was by threats, executions of deserters having been rising steadily. To compound the manpower drain, duels among the officers had become so common that the War Department had to ban the practice, threatening to dismiss any officers who engaged in them and survived.

Over two years of war had granted few real gains on the battlefield, while Federalist agitation raised the prospect of secession of New England. The American position in the war seemed only too well summed up by the blackened ruins of the White House and the Capitol building -- scenes that greatly discouraged Congress when the body returned to session in the city in the last half of September. Congress met in the Patent Office, since there were no other undamaged government buildings of adequate size left in the city.

A motion was put forward to relocate the government, at least temporarily, to another city, such as New York or Philadelphia. Southerners were against it, feeling such an arrangement might become permanent and grant more power to a Northern city than they liked. Besides, most of the government's staff lived in Washington, it would be a hardship for them to relocate, and it also demonstrated a certain defiance to continue to meet in Washington. The government stayed where it was. Work to repair the damage inflicted by the British was put in motion; Congress also authorized the purchase of all 10,000 volumes in Thomas Jefferson's library to restock the Library of Congress.

While the consensus had been to stay in Washington, that hardly meant much happiness over the fact. Bureaucrats had to rent out private buildings for their staffs and politicians similarly had to obtain quarters in private homes, leaving everyone irritable with the uncomfortable conditions and the high prices that had necessarily come along with them. Navy Secretary William Jones commented that Congressmen were "in bad temper, grumbling at everything." They were not any happier when Monroe came forward to propose to Congress expanding ground forces by 70,000 men, including 40,000 militia and 30,000 regulars. While Monroe was careful to soft-pedal the fact, the expanded regular force clearly implied conscription -- a concept against all good Republican principles -- and the reaction was strongly negative.

William Jones submitted his resignation as Navy Secretary that month, being confronted with personal problems over debt and no doubt sick of his thankless job. He would hang on until December, to be replaced by a Massachusetts businessman from the merchant trade with the grand name of Benjamin Crowninshield. Other cabinet members were quitting the administration as well, leaving Madison scrambling to find replacements willing to take on the impossible job of continuing the war. When the news of the status of the negotiations with Britain arrived in October, Madison and his people were discouraged at the severity of British demands. The final ruin of America's war with Britain seemed imminent.

BACK_TO_TOP* However, the American government had been encouraged by an honest victory in the north. After General Izard left Plattsburg for the Niagara district, Brigadier General Alexander Macomb had stayed behind with a force of about 3,300 men. The US Navy had a fleet of middling-to-small warships on Lake Champlain under Commodore Thomas Macdonough, the most formidable vessel being the 24-gun brig USS EAGLE. Navy Secretary Jones hadn't been keen on construction of the EAGLE, but Madison had insisted, and it tilted the balance of power on the lake to the Americans.

The British had assembled an invasion force of about 11,000 men under the command of General Prevost to drive down towards Plattsburg, many of the troops being veterans of the Napoleonic Wars. What Prevost's goal was remains fuzzy: he could have hardly contemplated a real campaign of conquest, it seems his intent was to improve the British bargaining position, and to help encourage separatism in New England.

Prevost was also not the best choice to command the operation. Although he was a competent war manager who had made most of the right decisions in directing the defense of Canada, he was no battlefield warfighter, and the troops and officers he took charge of did not find him inspiring. Few of them had been happy to have defeated Napoleon after years of war, only to be hauled off to another war across the ocean, and their morale was not the best. Prevost managed to make it worse through leadership by nitpicking; as is not unusual for soldiers on long campaigns, many of the officers who had arrived from Europe had become informal in their dress, and Prevost persistently nagged them about it. Combat soldiers are inclined to have a low opinion of headquarters operators, and to them Prevost seemed a perfect example of the type.

The British moved up the Richielieu River towards Lake Champlain and then crossed into New York state, brushing off such resistance that appeared without breaking column, arriving in front of the defenses of Plattsburg on 6 September. Prevost then went inert, waiting for the better part of a week for his own fleet to come up to neutralize the US Navy fleet, whose guns would certainly make an assault on Plattsburg difficult.

Macomb had received militia reinforcements and had about 4,500 men holding down a strong line of defense, though his militia weren't really up to any serious fight. Macdonough's warships were anchored in Plattsburg Bay, set up to bombard the British if they came into range. On 11 September 1814, the British fleet, under Captain George Downie, appeared and closed to engage. The two fleets were roughly equal in strength, but Macdonough's men were better trained and he was a superior battle leader. He arranged his ships at anchor in a way so that they could be maneuvered in place by hauling in or letting out anchor lines.

The British fleet closed in and there was a violent collision, the two fleets hammering it out for over two hours. Macdonough was personally knocked about several times by flying debris, including the head of one of his gun captains. The British still got much the worst of it, Downie being killed and their largest ships captured; the survivors fled. Macdonough would become the hero of the hour, being granted medals, monetary awards, and a thousand acres (400 hectares) of land not far from the lake. Macdonough was flabbergasted by his abrupt fame, commenting: "In one month, from a poor lieutenant I became a rich man."

With the failure of the naval effort, Prevost immediately called off a cooperative land attack and pulled back to Canada. He had good reason to do so: without control of Lake Champlain, he could not be supplied for a push south into New York state, and even holding Plattsburg would have been impractical over the long term. However, he could have made much more trouble for the defenders than he did, and the complaints against him grew in volume.

* Winston Churchill once claimed that the Battle of Plattsburg was one of the most strategically important victories in the history of the American continent. That seems overblown, since Prevost had no intention of penetrating deep into American soil, even if he had won; the Battle of Lake Erie was far more significant to the course of the war. However, at a time when the American war effort was in desperate trouble, a British invasion had been decisively repelled, encouraging the Americans and discouraging the British. In Ghent, Goulburn had been politely needling the Americans by suggesting they read the headlines of British newspapers, with Clay privately admitting that the news of the war made him "tremble" -- but now it was the turn of the British negotiators to scowl at the headlines. The US victories at Baltimore and Plattsburg reached Europe simultaneously, improving the bargaining position of the American peace commissioners.

Britain was confronted with the substantial challenges of establishing the order of a post-Napoleonic Europe. When the Duke of Wellington, who had led Britain's army to victory against the French, was asked to take command in America, he replied in his blunt way that victory there would demand a substantial further commitment of resources: "I feel no objection to going to America, though I don't promise myself much success there."

Sending a general and sending troops wasn't going to alter matters much; winning the war demanded that Britain win the financially ruinous naval arms race on the Great Lakes. Wellington concluded that, under the circumstances, the government had no right "to demand any concession of territory from America." When Wellington talked, people listened; Lord Liverpool, the prime minister, suggested to the British commissioners that they recognize "the inconvenience of the continuance of the war."

British businessmen were also weary of having their merchantmen seized by American privateers and US Navy corsairs. The Royal Navy certainly had the upper hand at sea, but completely suppressing the raiders wasn't in the cards, and they were making enough of a nuisance of themselves to cause pain. More significantly, the war interfered with the normal and profitable commerce between Britain and America, which was well more troublesome to British business interests than the privateers.

Britain's war with France had gone on for over two decades, leaving everyone weary of fighting, weary of paying taxes to support the fighting -- and taxes or not, British government coffers were running on empty, while the war across the Atlantic was expensive beyond any hope of reasonable return. Actually winning the war against the Americans would demand even greater expense. Realities were driving the British towards washing their hands of a conflict that had never amounted to anything more than a useless annoyance to them in the first place.

For the moment, however, both sides were ramping up their preparations for a harder war in the north. In October, Yeo finally launched his ship-of-the-line, the 112-gun HMS SAINT LAWRENCE -- though Lake Ontario soon froze over, and it accomplished nothing particularly warlike in the short time it had to cruise the lake. Yeo had two more ships-of-the-line, both with 120 guns, and another frigate under construction. The SAINT LAWRENCE did succeed in enhancing the fears of Chauncey, whose shipwrights were working on two American ships-of-line with 130 guns, and a 58-gun frigate. Once the spring of 1815 came, the two sides hoped to have more powerful fleets on Lake Ontario. Whether they would actually do much with them was another question.

BACK_TO_TOP* While the Royal Navy kept US Navy frigates bottled up in harbor through most of 1814, a few of the Navy's fast sloops managed to get to sea and raise hell. The USS PEACOCK, one of the six new sloops funded in 1813, left New York harbor in mid-March, capturing the 18-gun Royal Navy brig HMS EPERVIER on 29 April off of Cape Canaveral, Florida. After putting into Savannah, Georgia, for refit and resupply, the PEACOCK put to sea again in June, performing a loop for the rest of the year across the Atlantic and capturing 14 prizes.

The USS WASP, another one of the new sloops, left Portsmouth, New Hampshire in May. After capturing five prizes, the WASP had it out with the 18-gun Royal Navy brig-sloop HMS REINDEER on 28 June, the American warship prevailing after a short but very bitter fight, with the REINDEER burned in the aftermath. The WASP then put into the port of L'Orient in France to refit and resupply, taking two prizes along the way, to return to sea in early August. The WASP took another two prizes during August; then on 1 September cheekily took a prize from a convoy. That evening, the WASP got into a fight with the 18-gun HMS AVON, sinking the British vessel in the end. WASP took three further prizes, but after being spotted by a Swedish merchantman in mid-November, the vessel then disappeared with all hands -- sunk by a storm or freak wave or some other calamity. Nobody ever learned what happened to it.

Three other US Navy raiders were lost in 1814 as well, being captured after running into superior Royal Navy forces. The USS FROLIC, one of the six new sloops, was lost in April; the USS RATTLESNAKE, a 14-gun privateer bought up the US Navy, was lost in June; and the US SYREN -- a 16-gun brig built a decade earlier for the fight with the Barbary Pirates -- was lost in July.

Such losses were painfully expensive to a small force like the US Navy, but privateers were able to help keep up the pressure on British shipping. Marauders such as the PRINCE-DE-HEUFCHATEL, GOVERNOR TOMPKINS, and HARPY found the hunting good, capturing scores of vessels. So many British merchantmen were being captured in the waters around the islands that insurance rates soared.

While privateers were usually not interested in stand-up fights, they could fight hard when needed; when the privateer GENERAL ARMSTRONG was attacked that September by British boarding parties while in neutral port in the Azores, the Americans fought like "bloodthirsty savages", as one of the surviving British participants in the action put it, losing the ship but inflicting great slaughter on the British. They could have dash, too: one particularly cheeky privateer, Captain Thomas Boyle of the CHASSEUR, took his vessel on a raid into a British port, where he declared to the locals his personal blockade of Britain.

* Boyle was joking, of course; if the Royal Navy came out in force, he inevitably had to turn tail and run. American raiders on the high seas could not bottle up British ports, nor could they really do anything to interfere with the Royal Navy's blockade of American ports. Robert Fulton was among those who thought they could do something about the blockade, however.

Fulton developed a man-powered submarine named the "Turtle Boat", to be used to sneak up on a blockader at anchor and attach a torpedo under it; it was used for an attack on a Royal Navy vessel in June, but the screw intended to attach the torpedo broke off. It ran aground late in the month, and the British dispatched a team of marines to destroy it.

Fulton also designed one of the first steam warships, which was launched in New York Harbor in 1815; it was named FULTON THE FIRST in honor of Fulton, who abruptly died early in that year. It was a slow paddle-wheeled catamaran with thick wooden sides -- a crude weapon, but one that could have caused the British considerable trouble had it been available earlier. The Americans also launched the first two US Navy ships of the line in 1814, with the USS INDEPENDENCE launched in June and the USS WASHINGTON launched in October. Fitting them out proved time-consuming, however, and they never had it out with the Royal Navy.

BACK_TO_TOP