* At the start of 1814, it was obvious that the American war effort was not going anywhere in a hurry, and American government attempts to get the fight on track weren't going much more smoothly. At least America and Britain began peace negotiations in 1814, though the American negotiators were painfully aware of the weakness of their bargaining position. In one bright spot, Andrew Jackson was able to bring the fight against the Creek Red Sticks to a dramatic close, to then impose a punitive peace on Indian friends and foes alike. In the Niagara district, however, even hard-fought efforts by the Americans -- at Chippewa, Lundy's Lane, and Fort Erie -- failed to give them the initiative.

* While the Americans had achieved a number of successes during 1813 -- certainly they had done much better than they had in 1812 -- they had also suffered their fair share of reverses, and for the most part they were no better off at the beginning of 1814 than they had been a year earlier. The Royal Navy blockade of American ports had been extended to New England in April, effectively choking off almost all commerce. The US Navy's frigates remained bottled up in their harbors; at the beginning of the year, the USS ESSEX under Stephen Decatur still remained at large in the Pacific, but two Royal Navy warships, HMS PHOEBE & HMS CHERUB, hammered the ESSEX into surrender off the coast of Chile on 28 March 1814. Some small fast US Navy raiders and privateers were able to continue to fight, but they couldn't amount to anything more than a distraction to the British. Come the spring, the Americans would be strategically worse off, after Napoleon's abdication on 6 April freed British forces to focus on America.

Madison was still for continuing the fight, grasping at one glimmer of hope in the form of a truce ship that had arrived before the new year. While the British had made it clear they had no interest in Russian mediation to end the conflict, they were open to direct negotiations. Madison selected the existing team of Gallatin, Bayard, and Adams to conduct the negotiations, adding House Speaker Henry Clay of Kentucky and Massachusetts Congressman Jonathan Russell as reinforcements.

There were loud protests over the selection of Clay and Russell -- Clay being seen as too much of a "War-Hawk", and Russell being seen as lacking stature -- but all five commissioners were confirmed. Congress was, however, able to prevail on Madison to give up the fiction that Gallatin was still the "official" treasury secretary, all the more because Navy Secretary William Jones, to no surprise, found the burden of wearing a second hat as acting treasury secretary too burdensome: "I am as perfect a galley slave as ever laboured at the oar; the duties of both [offices] have become intolerable."

Madison chose Senator George W. Campbell of Tennessee to become treasury secretary. Campbell was confirmed, though he wouldn't prove very effective in the job. In any case, the Belgian city of Ghent was selected for the negotiations with the British, the American peace commissioners making their way there to begin talks.

* The problems of raising men and revenue that had plagued the American war effort from the start continued. Congress again raised bounties for enlistments, but getting the money for them was very troublesome. Although the new taxes had gone into effect at the beginning of the year, they were still grossly inadequate to fund the war, and so Congress authorized the government to take out loans and issue treasury notes. Nobody was too reassured by such measures, since they simply permitted the government to sink more deeply into debt.

One of the planks of Republican policy was a distaste for a central bank, and in fact the charter of the national bank established by Congress in 1791 had lapsed in 1811, with the government allowing it to die. A faction of Republicans, with support from Federalists, wanted to restore the bank, seeing it as a source of government loans that could be obtained on friendly terms. They were a minority, and the effort to re-establish a central bank went nowhere. Unfortunately, the attempt to obtain loans and issue notes didn't do much better, yielding only a fraction of the money needed -- few thought the government's credit was very good -- leaving the Madison Administration in desperate financial straits.

Trade policy was also in a state of chaos. The existing non-importation rule was being widely flaunted, trade with the enemy being so widespread as to be normal. The system was sometimes "gamed" as well, with "privateers" disposing of "prizes" that were obtained with a suspicious lack of violence, though there was no way to prove that payments had been handed to the "victims" under the table. To decisively choke off trade with the British, the Madison Administration had been pushing for a new version of the Embargo Act that would be well more restrictive than any preceding measures. Somewhat surprisingly, given the dodgy history of those measures -- not to mention the fact that American ports were under blockade in the first place -- the revitalized Embargo Act had been passed before the new year.

However, the vessel that had brought Britain's proposal for negotiations in late December had also brought news concerning Napoleon's defeat at Leipzig. Militarily defeated, the Emperor's Continental System had collapsed, and with it much of the formal rationale for trade sanctions. At the end of April 1814, Madison proposed to Congress that most of the trade restrictions be dropped. It was effectively conceding that such measures were counterproductive and bound to fail, but the president's reversal of policies in which he had invested so much effort proved a public shock, what a Republican paper called a "political earthquake".

Some of Madison's long-time backers were, as a Republican paper phrased it, "pretty warm ... and a little violent", but most Republicans just sighed and accepted reality, just as had the president. The Federalists couldn't have been happier, with Nathaniel Macon saying of them: "I have not for a long time seen the feds look in as so good humor; they all have a smile on their countenance." The revocation flew through both houses of Congress with overwhelming majorities; when the political earthquake subsided, all that was left outlawed was direct dealing with the enemy. Indirect dealings weren't covered, but they had been the status quo anyway, and now the government was no longer shooting itself in the foot over desperately-needed import duties -- no longer determined to punish its own citizens in its determination to punish the enemy.

At the end of the congressional session, the administration had got nearly all of what was wanted. It hadn't been easy, with members of Congress engaged in such interminable sessions of nitpicking debates and speeches that on occasion half of the seats in the House of Representatives were empty -- members preferring the congenial atmosphere of offices or pubs to being bored to tears. Republicans were still able to prevail; although the Federalists were able to tap considerable public resentment over the conduct of the war, they were still unable to take control of events.

BACK_TO_TOP* Through the winter of 1813:1814, Andrew Jackson remained at Forth Strother, hoping to rebuild his force. Much to his surprise, in early January about 800 new recruits showed up for duty there. Although these men were almost completely untrained and undrilled, Jackson decided to put them to use immediately.

William Weatherford and a large body of Red Sticks had set up a fortified camp near the confluence of the Tallapoosa and Coosa Rivers, building breastworks to plug up the neck of an isthmus of land established by a horseshoe bend in the Tallapoosa, manned by about 900 warriors, along with their women and children. Jackson marched his men to destroy the Red Stick base, but the Red Sticks got wind of his movement, and on the morning of 22 January 1814 attacked Jackson and his men at Emuckfaw Creek, a few hours of march from the Horseshoe Bend encampment. Jackson's own spies had reported the Red Sticks making preparations for the attack the evening before, so he wasn't taken by surprise -- but the Red Sticks pressed his men very hard and likely would have massacred them, had the Indian plan of attack been better implemented.

Jackson, realizing that his green troops really weren't up to serious fighting and that he didn't really have enough men anyway, decided to march his force back to Fort Strother. The Red Sticks followed him, however, and attacked as Jackson's men were crossing Enotachopco Creek on 24 January. Jackson's rear-guard panicked and fled, but he was able to drive off the Red Sticks, inflicting heavy losses on them, discouraging them from further attacks. However, his own losses were not trivial and Jackson understood that if it hadn't been for dumb luck, he might well have been hurt much worse. He realized couldn't take to the field again until he had a more effective force.

The two battles were played up as victories back in Tennessee, attracting public attention and more recruits, and so by February Jackson had about 4,000 men, including 600 Army regulars. One of the additions was a regiment led by a strapping young man named Sam Houston, who would later become another hero in the fight for Texas. Houston, who had lived among the Cherokees for five years, had a deep understanding of the Indians, and also a high regard for Jackson, Houston seeing him as a fearless patriot.

The Army regulars were particularly welcome, Jackson deciding to use them to drill and otherwise impose discipline on his unruly militia. He went to severe lengths to show the militiamen that he meant business. When an 18-year-old militiaman named John Woods threatened an officer with a musket after a dispute, Jackson was enraged: "Which is the damned rascal?! Shoot him! Shoot him! Blow ten balls through the damned villain's body!"

And so, after a perfunctory court-martial, Wood faced a firing squad on 14 March. For the rest of Jackson's life, the incident would be used by his enemies to demonstrate what a monster he was -- but the immediate effect was that, as one of Jackson's officers wrote: "A strict obedience afterward characterized the army."

With such obedient soldiers and continued drill, Jackson felt able to go on the offensive. Late in the month, he took to the field with about 3,000 men to assault the Red Stick position at Horseshoe Bend. When Jackson arrived, he was impressed with the stoutness of the Red Stick position; Indians were not usually much at fortifications, but they had laid out their defensive line well to provide a field of fire that made an assault extremely dangerous. It was fortunate in a sense that Jackson's January expedition hadn't made it there, since the result would have almost certainly been failure.

Jackson had about 2,000 militia and volunteers, nearly 600 regulars, several hundred friendly Cherokee and Creek Indians, and a few pieces of artillery. His objective was not the capture of the camp but the destruction of the warriors there, and so he deployed Coffee and his cavalry, along with the friendly Indian force, on the far side of the river to deal with any Red Sticks trying to escape. At mid-morning on 27 March, Jackson threw his men against the Red Stick line; progress was slow at first, but then the Cherokees on the other side of the river decided to cross over and attack as well, with some of Coffee's cavalrymen cooperating.

The attack from the rear did much to confuse the defenders, and when Jackson ordered a full assault on the breastworks, his troops managed to penetrate the barrier -- Sam Houston was one of the first over the top, though he took an arrow in the leg doing it. The Red Sticks fell back and fought from improvised strongpoints, with the struggle going on all the rest of the day and then, after darkness put a temporary halt to the fury, the next morning. Red Sticks who tried to escape across the river were killed. By the time the mopping-up was completed, hundreds of Red Sticks had been slaughtered, with Jackson's men taking trophies from the dead. Jackson reported: "I lament that two or three women and children were killed by accident." His casualties amounted to only a few dozen men.

Jackson had won a decisive victory against the Creeks at Horseshoe Bend, though he still had no reason to think the war against the Red Sticks was over. William Weatherford had been absent from the battle and remained at large, and Jackson hardly believed he had killed all the Red Sticks. He spent the next two weeks destroying Indian villages in the area, though they were typically deserted, the inhabitants having realized they were defenseless and run away. In mid-April, he and his men took over an old abandoned French fort not far from Horseshoe Bend and built it up, the men naming it "Fort Jackson" after their commander.

Jackson remained concerned about William Weatherford, but Weatherford decided to call it quits; he no longer had a force of warriors large enough to effectively carry on the fight, and he had a large number of women and children to protect. In late April, Weatherford simply walked into Fort Jackson and gave himself up to Jackson personally, proclaiming: "My people are no more! Their bones are bleaching on the plains of Tallushatches, Talledega, and Emuckfaw."

Jackson had plenty of good reason to order Weatherford hanged, but realized that it was in the Creek chieftain's power to persuade surviving Red Sticks to surrender. Weatherford promised to do so, and Jackson accepted it, simply releasing him -- after warning Weatherford of dire consequences if he didn't keep his word, while promising protection if he did. Jackson didn't go idle after releasing Weatherford, sending out what might be called in more modern terms "search and destroy" patrols to find and deal with Red Stick holdouts. Faced with annihilation, Red Sticks went forward to surrender in numbers. The little war with the Creeks was over, and Jackson dismissed his militia so they could return to their homes in Tennessee.

Jackson's victory over the Red Sticks impressed the leadership in Washington. There being a desperate need for officers who could win battles, in June Jackson was made a major general in the Regular Army and assigned regional command. Congress had to approve any additions to such a rank -- but William Henry Harrison, having grown tired of being snubbed by the War Department, submitted his resignation, and so a slot came open for Jackson.

* The little war with the Red Sticks was over but the paperwork remained, and the paperwork turned out to be anything but inconsequential. In July, Jackson called all the Indian chiefs in the region to Fort Jackson, making it clear that a failure to comply would be unwise. Friendly Creek chiefs found the threats of force accompanying the "invitation" puzzling, but having backed Jackson in the war against the Red Sticks, they had no reason to read much into the matter. When the meeting took place on 1 August, however, they found that Jackson felt no gratitude for their support in the conflict; when the terms of the settlement proposed by Jackson were read out to them, they found out to their shock that he intended to strip the Creek nation of half its land. He also demanded land concessions from the Cherokees, despite the fact that they had fully supported him against the Red Sticks.

Jackson intended to break the promises that the government had made to the tribes. Jackson rationalized, with dubious sincerity, that with less land the tribes would be forced to settle down instead of wandering, setting up proper farms and towns, and so reduce tensions with the white settlers. If the peace were not kept, the tribesfolk would be destroyed, so the treaty was in their best interests -- if in the same sense that it was in the best interests of a victim of a robbery to hand over the money to an armed bandit instead of being killed.

The chiefs protested bitterly at the injustice of Jackson's demands, but he contemptuously replied that they had brought it on themselves by not turning over Tecumseh to the government when he had visited the region in 1811. The pleas continued, the chiefs pointing out that Jackson had not seen the need to make an issue of Tecumseh when the general had wanted their help, but the general was indifferent. The chiefs had no choice: Sharp Knife would crush them if they opposed him. In addition, the unrest had left many of the tribespeople in a destitute and starving condition, and Jackson promised them, in sincerity, food and clothing for their cooperation.

On 9 August, the chiefs signed the Treaty of Fort Jackson, most doing so under protest; only one of the signatories was a Red Stick chief, Jackson in effect having imposed a punitive treaty on his own allies. The government found the terms of Jackson's treaty harsh but Westerners were thoroughly enthusiastic, and when the government in Washington later tried to alter parts of the treaty in favor of the Indians, angry local reaction and Jackson's public stature ensured it didn't happen.

BACK_TO_TOP* While American control over the Northwest had been consolidated in 1813, Fort Detroit remained an isolated post in wild territory, difficult to supply in the winter when Lake Erie froze up. That led to American raids on Canadian farms in the regions of Upper Canada north of Lake Erie. In January 1814, Colonel Anthony Butler, military commander in the region, learned that the British were planning a winter offensive against his forces, and so sent his troops out on a much more comprehensive operation to seize stores from Canadian farms and towns, then burn what was left behind to deny it to the British.

To the extent that the Americans cared to justify such an action, the British depredations in the Niagara district were cause enough. The days when Americans believed that Canadian Late Loyalists would be sympathetic were long gone; the Late Loyalists, as both sides had found out, generally cared very little about anything but their own interests. Now the Americans had gone to the other extreme, having concluded that all Canadian citizens were enemies.

The British offensive didn't come off, being frustrated by a mild and muddy winter. However, General Drummond took offense at the American plundering of the area and dispatched about 300 men to deal with them. On 4 March, the British troops met up with an American force of about half their number at Long Woods, about 110 miles (175 kilometers) northeast of Fort Detroit. The Americans, under the command of Captain Andrew Holmes, were in a strong position, on a hill and protected by a log barricade, and the British were "shot to pieces". They had to retreat, being taken off the playing board. American newspapers made much of the victory at Long Woods.

* The papers did not make so much of a fuss over an action some weeks later, when eight vessels departed from Presque Isle carrying 700 Pennsylvania volunteers under Lieutenant Colonel John B. Campbell. The little fleet sailed almost due north across Lake Erie to make landfall at the town of Port Dover on 15 May. Instructed by the example of what had happened to Buffalo the year before, they diligently shot livestock and put buildings to the torch. A local girl, Amelia Ryerse, described the scene: "Very soon we saw columns of dark smoke arise from every building, and of what had been a prosperous household, at noon there remained only smouldering ruins." A Pennsylvania soldier was appalled, saying the "destruction and plunder" engaged in by the invaders "beggars all description."

Having accomplished their mission, the Americans then departed. Isaac Brown wasn't happy with the action, offering apologies to his British counterpart and ordering that Campbell be court-martialed. Given the mutual escalation of brutalities, few other Americans were all that upset about Campbell's excesses, and to Brown's annoyance all Campbell got out of the court-martial was the mildest of reprimands. He would soon be promoted to colonel.

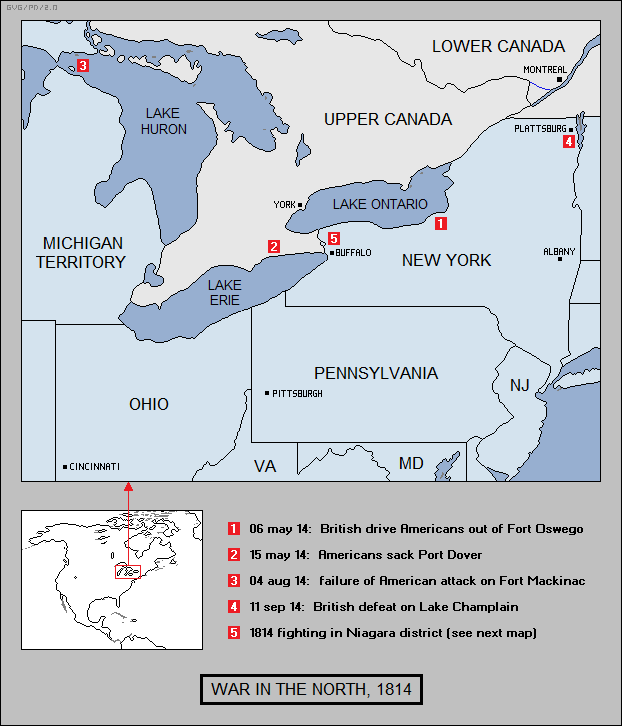

The papers also did not make so much of a fuss over an American effort to retake Fort Mackinac. The fort, being at the straits between Lakes Superior and Huron, provided a neat chokepoint that blocked American maritime movements in the region, and so there was good reason to try to recapture the installation. Come the summer of 1814, Captain Arthur Sinclair, who had replaced Perry in command of the Lake Erie fleet, sailed several of his ships north into Lake Huron, carrying about 700 men under Major Croghan.

After landing at Sault Saint Marie in late July, the Americans prepared to assault the island fortress -- though it was an intimidating prospect, Sinclair calling it a "perfect Gibraltar". The guns on his ships couldn't be elevated high enough to hit the British fort, and so Croghan's men had no benefit of naval support. On 4 August, an American force trying to advance on the fort through the forest ran into an ambush set up by the British and their Indian allies, driving off the Americans in confusion and inflicting a disproportionate number of casualties on them. Two schooners were lost in the fight as well, with the Americans then deciding to call it quits and slink off back home. Sinclair left two ships behind to blockade the fort, but they were lost a month later, a British party stealthily boarding one in the dark and then using it to capture the second. The Americans didn't try to recapture Mackinac again.

Having failed in that effort, in the fall American forces under Brigadier General Duncan McArthur returned to Upper Canada to lay it to absolute waste. McArthur was so enthusiastic in his destruction that he even proposed to give the same treatment to Michigan Territory come the spring of 1815, destroying everything except garrison posts -- his rationale being that the territory was "not worth defending and merely a den for Indians and traitors." Fortunately, McArthur would not have the opportunity to put his plan into action.

* In the east, General Wilkinson's command finally fizzled out to its sorry end. Recognizing that French Mills was a poor place to keep an army -- Federalists in the region were busily sending out reports of the bad condition of the troops there -- in mid-February, War Secretary Armstrong had ordered Wilkinson to withdraw his troops, with half sent to Sackets Harbor and half to Plattsburgh. The soldiers burned everything they left behind, including the fleet of boats on which so much effort and expense had been expended.

Wilkinson tried to save himself by taking to the field again in March 1814, advancing across the Canadian border from Plattsburgh with 4,000 men. They soon encountered a few hundred British troops at a strongpoint at La Colle; after a noisy but generally bloodless exchange of fire -- the Americans didn't have the capability of doing the defenders any real harm, and sensibly didn't press their attacks with any earnestness -- Wilkinson turned his men around and marched them back home again. Even Republican papers screamed for his head; War Secretary Armstrong removed him from command. Wilkinson once again faced a court-martial, but that was a game he knew how to play very well, and once again he would be acquitted.

BACK_TO_TOP* While the British were increasing their troop strength in Canada, the Americans were matching them with troop increases of their own. In addition, Secretary of War Armstrong could sometimes recognize military leadership talent and make use of it. Armstrong promoted Jacob Brown to the rank of major general and placed him in command of the Niagara-Lake Ontario theater. To replace Wade Hampton, Armstrong promoted Hampton's executive officer, George Izard, to major general and gave him command of the Lake Champlain frontier; Winfield Scott was made a general as well, and placed in command at Buffalo.

The naval arms race on Lake Ontario had continued in the meantime. During the winter, Yeo had overseen the completion of two frigates at Kingston, with work proceeding on a full ship-of-the-line. At Sackets Harbor, Chauncey was working on two frigates of his own -- the 42-gun USS MOHAWK and the 58-gun USS SUPERIOR. Given the timidity of the two opposing naval commanders, the struggle for control of the lake had devolved to what was called a "battle of the carpenters", as each side drove to build up naval forces to cow the other.

The single-minded push for more powerful warships antagonized ground commanders on both sides as they watched the arms race soak up resources. Chauncey reacted to complaints on the matter with general indifference, an indifference he also gave to the unfortunates under his command. Sackets Harbor didn't have the resources to support the hordes of military men and workers assembled there; the men were poorly housed and poorly fed, living in squalor and disease.

In early May, the British felt they had the upper hand on Lake Ontario, with an amphibious assault descending on Fort Oswego, south on the short of the Lake from Sackets Harbor, on 6 May. The American defenders gave a fair account of themselves, but they were outmatched and forced to pull out. The British captured substantial amounts of supplies and then withdrew themselves, burning the installation behind them. Yeo then set up a blockade on Sackets Harbor; the Americans took to running convoys of bateaux along the shorelines at night, in waters too shallow for the larger British ships to maneuver. On 20 May the British tried to break up a flatboat convoy, but the Americans went up the Big Sandy River, set up an ambush, and managed to grab two British gunboats that went in after them, as well as shoot down dozens of redcoats to a handful of casualties of their own.

* By June, Chauncey had his frigates MOHAWK and SUPERIOR on the lake, balancing the opposing British fleet. On the Niagara frontier, the Americans were preparing for another move against the British. Jacob Brown crossed the Niagara River on 3 July with his force of 3,500 men, having explained his goals for the operation in abstract terms to one of his officers who recorded Brown's comments for posterity: "If we could do nothing else, we might at least strike such a blow as to restore the tarnished military character of the country, which ... was an object worth the sacrifice of the whole force which he commanded."

The men had been heavily drilled by their officers, Winfield Scott said to have marched them and damned them all day long; he was a giant of a man, able to impose discipline on them by his presence. The troops were dressed in white pants and gray jackets, for the simple reason that blue cloth wasn't available. Brown's officers had collectively resolved as "a point of honor to go into action with sashes and epaulettes and to wear [them] throughout the campaign." It might seem absurd in hindsight to have worn bright red sashes and gold trim well suited to the parade ground that, in battle, was guaranteed to draw fire -- but they were perfectly aware that they were enhancing their risk. That was the point of the exercise: if they were to go down, they would do so showing the British what they were made of. Many in the ranks were infected to a degree with the same spirit of daring.

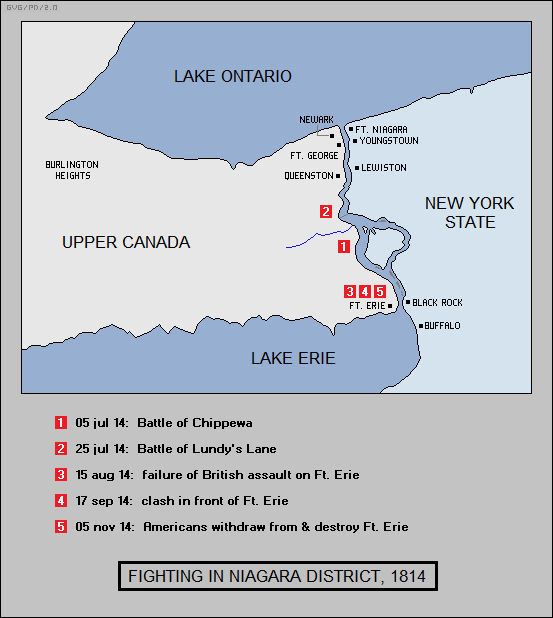

American boats landed before dawn in the fog. Winfield Scott, demonstrating a typical excess of dash, was in a bit too much of a hurry to step off his boat and nearly drowned, but the force landed without serious hazard and quickly surrounded Fort Erie. Completely surprised and unprepared, the British commander of the fort surrendered without much of a fuss. The victors marched triumphantly into the fort, the fifers and drummers proudly rolling out "Yankee Doodle".

General Drummond was away at York, and so the defense fell to General Riall. The Americans advanced north towards the Chippewa River, 16 miles (26 kilometers) from Fort Erie. There was only one bridge across the Chippewa and Riall, who had about 1,500 men under his command, could have set up a solid defensive line on the river's northern bank. However, his experience with the Americans the year before had led him to believe that he was once again facing a mob of worthless militia who would cave in on the first display of British force, and so on 5 July he marched his men south to confront the Americans.

Riall was very much mistaken, though the first American troops he encountered were volunteers, the British brushing them aside easily. However, having done so, he was then confronted by a brigade under Winfield Scott. Riall assumed they were militia as well thanks to their gray uniforms -- but when his own men went forward, they found the American line painfully solid, with Riall supposedly saying: "Regulars, by God!" That at least was as Scott had it later; Riall was certainly shocked when the Americans broke his own line, sending him and his men back across the Chippewa to the safety of their defenses.

The Battle of Chippewa cost both sides hundreds of casualties. The Americans had clearly won the fight and exulted in the triumph, even fishing for compliments from British prisoners. Riall's Indian auxiliaries, having lost confidence in him, abandoned him. Observing American flanking moves around his position on the Chippewa, on 8 July Riall abandoned his position and withdrew to the security of Fort George. The next day Brown moved north to Queenston -- where his foraging parties made a nuisance of themselves to the locals, Riall registering his satisfaction with the energy with which Canadian militia took on bands of marauding Yankees.

Canadian resistance of course only made the Americans more savage; after a skirmish on 18 July, a group of volunteers under Lieutenant Colonel Isaac Stone trashed and torched the village of St. David, to the west of Queenston. Brown was not happy with such indiscipline; having thrown Campbell to a court-martial only to see him all but praised, Brown simply dismissed Stone from the Army the next day -- an action that caused considerable resentment among the volunteers, who believed that whatever bad treatment the damned Loyalists got was better than what they deserved.

BACK_TO_TOP* The victory at Chippewa hadn't actually accomplished much in specific; to obtain a real advantage, Brown had to seize both Fort George and Fort Niagara. To do that he needed support from Chauncey's warships, but Chauncey had made it perfectly clear to Brown that the Navy was not going to act as "an appendage to the Army." Chauncey believed that the Niagara district was of no real strategic importance, and told Brown he ought to take his troops to Sackets Harbor to support a move on Kingston. There was a certain fair logic in Chauncey's thinking, but many officers under his command realized that it made no sense for the Navy to sit by idly while the Army fought and bled. Unfortunately, although Chauncey was in bed with malaria at the time, he refused to allow his lieutenants to take the fleet to Brown's assistance.

Brown, getting nowhere, pulled back to a more secure position on the Chippewa on 24 July, to refit and prepare for an assault on the Burlington Heights. However, the British had plans of their own; braced by reinforcements from Europe, they were transferring troops from York and Kingston, unhindered by Chauncey's fleet, to confront the Americans on the Niagara frontier. British forces had followed Brown's withdrawal. On 25 July, concerned about the movements of the British, Brown ordered Scott to take his brigade back on the road to Queenston in hopes of disrupting British movements. Scott advanced to a crossroads named Lundy's Lane, and late in the day unexpectedly ran into the British.

The result was one of the most savage battles of the war, mostly fought in the dark, with the inevitable consequence that both sides occasionally fired on their own. Confusion was magnified by the fact that both sides spoke the same tongue, with a British participant describing the situations that arose: "Who goes there? -- A friend. -- To whom? -- To King George. If the appellants, as you would call them, were of that persuasion, all was well, but when a friend to Madison, then there was a difference of opinion."

The British outnumbered Scott's men, but the Americans were not intimidated, throwing back British attacks, attacking and being thrown back in turn. After two hours of fighting, both sides began to receive reinforcements; ultimately each side had about 2,900 men in the fight. The fighting continued inconclusively until about midnight, when Brown ordered Scott's force to pull back across the Chippewa river. The British were too cut up to follow.

Both sides took about 850 casualties. Scott was wounded in the shoulder and would not see further action in the war; Brown was shot in the thigh; while General Riall was captured when he walked into a group of American soldiers in the dark. Both sides claimed victory, but the fight was a draw. It might be better said both sides took a whipping, having accomplished nothing more than to pile up dead and wounded.

* A few days after the Battle of Lundy's Lane, Brown pulled his force back to Fort Erie to the south, where they braced up the defenses. The British followed and laid siege to the fort in early August. To cut off the defenders from resupply General Drummond, who had returned from York, sent a raiding party across the river against Buffalo on 3 August, but the Americans were more warlike than they had been the year before, and the raiders walked into am ambush. The British suffered some casualties and became unnerved, returning to their own side of the river; Drummond was furious, accusing his men of cowardice.

From 7 August, the British bombarded the fort, to no great effect until 14 August, when a magazine blew up with a loud explosion. Drummond believed, incorrectly, that he had done the Americans serious damage, and so he ordered an assault to take place the next morning. Three columns were to attack the fort simultaneously with Drummond, who still believed his men were timid, insisting that the attackers rely on the bayonet, and ordering them to charge without fitting flints to their muskets lest they give themselves away.

The night was too dark, the plan of attack too complicated; the Americans were alert, and the British suffered badly trying to get into the fort. They did manage to get inside and raise hell, with one of the leaders of the assault -- Colonel William Drummond, the general's nephew -- shouting to his troops for all to hear: "GIVE THE DAMNED YANKEES NO QUARTER!" To underline the point, Drummond then shot an American officer who was trying to surrender; a few moments later Drummond took a ball in the heart, fired by an American soldier who had found the loudmouthed redcoat annoying.

The fight dragged on until both sides noticed, as an American lieutenant commented later, "an unnatural tremor beneath our feet, like the first heave of an earthquake." There followed a tremendous explosion as a magazine brewed up. To this day, nobody knows why it did so, whether it was due to some accident or the act of a defender who didn't live to talk about it; but the British were caught in the open, many of them blasted into the air, as the cartridges in their cartridge boxes popped off like firecrackers. Some American witnesses later claimed the British attack had already been broken by that time -- but in any case, after the explosion, the surviving British scrambled back to their own lines in haste.

General Drummond called the conduct of his men "disgraceful", conveniently disregarding his poor planning of the battle -- though it did not escape the notice of General Prevost. The British had simply been handed a terrible defeat, losing hundreds of men to dozens of the defenders, one American soldier saying that in the aftermath there were "legs, arms, and heads lying in confusion", with another summing it up with: "I never before witnessed such a scene of carnage and havoc among human beings."

BACK_TO_TOP* Drummond, for want of anything better to do, went back to bombarding Fort Erie. Both sides otherwise passed the time with purposeless small-scale raids on each other's lines. Brown was encouraged to withdraw, the American presence at Fort Erie being both militarily insignificant and precarious -- but instead he called on the New York state government for militia to brace his force, with several thousand militiamen arriving in Buffalo in early September. They were reluctant to leave New York soil, but Brown was able to prevail on about half of them to cross the river to Fort Erie.

Meanwhile, rains had been falling steadily, reducing the British positions around the fort to swampland. Drummond's men were increasingly falling ill and he was running low on food, being forced to put his men on half-rations. On 16 September, Drummond decided to face reality, and call it quits. However, while the British were pulling out on 17 September the Americans performed a sortie in force in the rain and darkness, to overrun two batteries where they spiked the guns, and blew up the magazines. Drummond threw his men back at them but the Americans, having made their point, then withdrew back to the fort. The action was bloody, with hundreds of casualties on both sides, but inconclusive -- though the British did get somewhat the worse of it, and so the Americans were given yet another boost to their morale.

In the meantime, General George Izard was marching 3,500 troops from Plattsburgh to the Niagara district, in principle to support Brown. Izard was not happy with the move, thinking Plattsburg offered more opportunities, but War Secretary Armstrong ordered it done, and so it was done. Izard was not made any happier by the fact that it would have been much easier to march to Sackets Harbor and have Chauncey's ships haul his troops across Lake Ontario, but as usual Chauncey refused to cooperate. Izard's force finally reached the Niagara district on 10 October -- after 40 days of march in which one of the most powerful US Army forces in the region had been effectively removed from the playing board, a fact which didn't escape the notice of the British.

Izard outranked Brown and so took command of the combined force, which handily outnumbered Drummond's. Izard spent about ten days performing inconclusive maneuvers and then decided it wasn't worth the bother, feeling with good reason that the Saint Lawrence valley was a much more worthwhile theater of operations. Still, with a superior force the Americans had been in a position to crush Drummond, and Brown smoldered that it wasn't done. In any case, Izard gave up the campaign, allowing the volunteers to go home while his soldiers set up for the winter around Buffalo, building shelters to keep out the snows -- except for about 2,000 of them, who Brown marched off to Sackets Harbor to brace up the defense there. It wasn't a duty assignment that made Brown any happier; after he arrived, Brown and Chauncey spoke to each other as little as possible.

* Izard left a garrison at Fort Erie, it seems partly for the honor of the thing, but also as a bargaining chip in peace negotiations. However, as the weather grew colder he began to worry that as the river froze up the garrison would be isolated, neither able to withdraw nor be resupplied. The garrison withdrew on 5 November, blowing up the fort behind them. A British officer found the sight impressive: "The explosion was tremendous, and worth seeing." When the British inspected the ruins, they found nothing intact. The important thing, of course, was that the Americans were gone, and another British officer gloated: "The campaign has ended as usual, unfavorable to the United States arms; as they are not in possession of a foot of ground in Canada."

The Americans wouldn't come back across the Niagara River in force again; the fighting in the district had effectively come to an end. Brown could take pride in the fact that his troops had indeed fought well at Chippewa, Lundy's Lane, and Fort Erie. War Secretary Armstrong wrote him: "You have behaved nobly. You have rescued the military character of your country from the odium brought upon it by fools and rascals." Brown himself was particularly pleased with the conduct of the militiamen; nothing much could have been expected of them earlier, but now he praised them for having "behaved gallantly".

Brown had to privately agree that the British were right, that the fighting had accomplished nothing tangible for the United States, saying "the general execution of the plan of campaign has been disgraceful." Brown saw the disgrace as starting with Madison and working its way down. The glory that the Americans won on the battlefield had been obtained by all but wrecking the little army that Brown and his officers had so painfully built up, leaving nothing in condition for greater efforts any time soon. Given the near bankruptcy of the government, there was no prospect of rebuilding the force -- even maintaining it as it was seemed problematic. The one saving grace of the blood expended by the Americans on the battlefield was that it helped convince the British that further fighting with the Americans was likely to be expensive. There was no prospect of the Americans winning the war; but they might be able to save the peace.

BACK_TO_TOP