* The Americans renewed their attempts to conquer Canada in 1813, with results roughly as dismal as they had been the year before; to compound the humiliation, the British hit the Americans hard in the Niagara District, inflicting widespread destruction. In the Southwest, in response to an uprising by a faction of Creek Indians known as the "Red Sticks", a Kentucky militia force under Andrew Jackson took the field, though with ambiguous results for the moment. At sea, the US Navy was increasingly constrained by Royal Navy power, which the British also employed to perform attacks on American coastal communities.

* The British and Indian survivors of the fiasco on the Thames made their way through the woods to the west. The British, fearing that Harrison planned to pursue and worried that their forces on the Niagara frontier would be bottled up, withdrew to the more defensible position on the Burlington Heights in early October.

The Americans didn't pursue. The new American commander in the region, Major General James Wilkinson, had arrived in Sackets Harbor on 20 August, having been previously in command in Louisiana. The intent was that Wilkinson would conduct an offensive to capture Montreal, and he looted the Niagara frontier of regular troops for the purpose; although Harrison arrived by ship with a force of 900 at Niagara during October, he and his men were promptly put on the march to Sackets Harbor. The Niagara frontier remained a neglected theater of war, under the nominal direction of George McClure, an Irish-born brigadier general of the New York militia.

War Secretary Armstrong had originally pushed for a drive on Kingston, but Wilkinson had convinced him, with good reason, that Montreal would be the more important strategic target. The assault on Montreal was to involve a parallel drive by two substantial forces:

There was something unpleasantly familiar about the arrangements for the offensive. Neither force was big enough to take Montreal on its own, and Wilkinson had no confidence in Hampton. Hampton had no confidence in Wilkinson either, though he was far from alone in his opinion; Wilkinson was regarded as an extremely dubious quantity by those who took orders from him, sometimes described as a "conman in uniform".

People who met Wilkinson for the first time were often impressed. In appearance, he was no rugged soldier, being clearly well-fed and fond of comfort, but once he started talking, people found him charming, confident, enthusiastic, with a strong streak of military optimism -- a far cry from his inert predecessor Dearborn. Republic politicians thought him a military genius, the answer to their prayers. Those who actually dealt with him in practice quickly realized that his impressive appearance was completely deceptive, that he was entirely treacherous to deal with, being dishonest, corrupt, interested only in self-advancement, totally unconcerned in the welfare of his troops or in effective military action. It wasn't known at the time, but he'd actually been a paid agent of the Spanish -- who, characteristically, he betrayed in directing movements against them.

Winfield Scott had been under Wilkinson's command, with Scott describing the situation as like "being married to a prostitute." Scott said that he'd carry two pistols if he went into battle with Wilkinson, with one to shoot the enemy, the other to shoot Wilkinson. Scott was so loud in his contempt for his superior officer that he was put before court-martial for insubordination in 1810 and suspended for a year without pay. Hampton had also served under Wilkinson and had no illusions about him.

Wilkinson's shady dealings led to his own court-martial in 1811, but he had a definite skill for playing court proceedings, and he was acquitted -- though as one observer put it, "many very queer transactions ... were exposed." Louisiana had become a state in the Union on 30 April 1812, and the Louisiana delegation in Washington pressed the government to kindly remove him. Wilkinson had gone to Washington, where he energetically lobbied for his new command. For whatever reasons, War Secretary Armstrong decided to put Wilkinson in charge in the north.

Wilkinson's strategic focus on Montreal was sound, but that was the only element in his thinking that was. One of the big problems was that Wilkinson got started late in the year, in territory noted for its unpleasant winter climate. He didn't really get started until mid-October, when he shifted his forces from Sackets Harbor to Grenadier Island, in the Saint Lawrence inlet. The troops were exposed to harsh and stormy weather that wrecked many of their boats, ruined a substantial portion of their food supplies, and reduced many of them to disease. Wilkinson was among the ill, with the general using whiskey and laudanum to brace himself up. That didn't improve his judgement in any degree, one of his officers describing him as "very merry".

Wilkinson finally set out with his force down the Saint Lawrence on 2 November. Republican papers played up the expedition, proclaiming final victory was just around the corner, but people on the spot knew better. Judge Nathan Ford, a prominent New York Federalist and a persistent thorn in the side of the Madison Administration, observed Wilkinson and his little army, to describe it as "weak beyond measure" and branding it a fraud: "Those who live upon the lines know & see the shameful deception which is played off on the credulity of those who are remote from the scene." Ford granted Wilkinson "a pattent right for superior stupidity."

Wilkinson's men made a nuisance of themselves wherever they came ashore with their looting and other malicious amusements. A British force of 1,200 men under Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Morrison finally confronted the Americans on 11 November at Crysler's Farm, on the Canadian side of the river; although almost twice as many Americans were sent into the fight, they were largely undisciplined in battle, and the British sent them packing. The Americans lost over a hundred dead, many more wounded, with British losses about half that.

* Even before Wilkinson had got underway, Hampton's supportive drive had fallen apart of its own dead weight. Hampton had advanced north across the border, to then run into a small force of Canadian militia under Lieutenant Colonel Charles de Salaberry set up near the Chateauguay River, south of Montreal, on 26 October. Hampton outnumbered the British by almost ten to one, but the defenders were well set up behind log defenses in terrain that favored the defense. Hampton tried to split his forces and catch the British in a two-pronged attack, but swamps and other difficulties disrupted the assault into incoherence, while the Canadians poured fire into the Americans whenever they had the chance. Hampton finally called it quits and went back to where he had come from, even though he had only suffered less than a hundred casualties. Chateauguay was a bright victory for the Canadians, with both French- and English-speaking militiamen enthused at driving off the American rabble.

Wilkinson got the news of Hampton's defeat on 12 November and used it as an excuse to give up his own effort. He pulled back to French Mills, just behind the New York state border, claiming he planned to renew the offensive once weather permitted. There were almost no facilities at French Mills, however, and the place was difficult to supply, with the result that Wilkinson's men died in scores of disease and deprivation through the winter. The climate there was bitterly cold, one officer writing: "You can almost gather in the Atmosphere by handfulls as you do Water. Several Sentinels, have frozen to death on post and many are badly frostbitten."

BACK_TO_TOP* In the meantime, the neglect of the Niagara frontier had led to calamity there. McClure had been talking up a tough war with the militia under his command -- but he was unable to make any good use of them, only obtaining insubordination, unruly conduct, and desertions. While his force disintegrated, the British command was braced by the arrival of Lieutenant General Gordon Drummond, who had replaced General Rottenburg as lieutenant general of Upper Canada. Rottenburg had been seen as timid and lacking in initiative; Drummond didn't have those problems.

On 10 December 1813, confronted by a buildup of British troops around Fort George, McClure decided he couldn't hold the installation with the handful of militia there and pulled out across the Niagara, with the men burning the town of Newark behind them -- but leaving in such haste that they failed to do more than spike the guns of the fort, even discarding large numbers of tents and other material that fell into British hands. The burning of Newark infuriated the British, McClure commenting that "the Enemy is much exasperated and will make a descent on this frontier if possible."

McClure was perceptive of British intent, but the garrison at Fort Niagara remained complacent. Thanks to snowy winter weather, the Americans didn't think an attack was imminent -- but in the predawn hours of 19 December, about 550 British troops under Colonel John Murray crossed the Niagara, quietly bayoneted American guards, and then simply charged through the fort's open gates, putting the bayonet to everyone they saw. The fort commander, Captain Nathaniel Leonard, promptly surrendered. The British captured 27 cannon, thousands of small arms, stockpiles of ammunition, and worst of all the bulk of American food stores in the area. Not only had the British seized the most significant American strongpoint in the region, they had also rendered American operations there logistically impractical.

A second attack was performed immediately following the surrender of Fort Niagara by a force of about a thousand British troops and Indians under Irish Major General Phineas Riall, resulting in the pillaging and burning of the town of Lewiston near the fort. The British then hit south, attacking Black Rock and Buffalo on the morning of 30 December, scattering the militiamen to then sack and burn the towns. The Americans could only fall back to a line well away from the river and hope the British didn't try to push any farther. They didn't; the only real estate they retained on the east side of the Niagara River was Fort Niagara, which they held to the end of the conflict.

The disinclination of the British to press their advantage was the only good news in the fiasco. The Americans had suffered a tremendous disaster, with New York Governor Daniel Thompkins lamenting the destruction in the Niagara Valley: "The whole frontier from Lake Ontario to Lake Erie is depopulated & the buildings & improvements, with a few exceptions, destroyed." McClure, jeered at by all and with good reason to fear his own troops, went home; he wasn't missed. Federalists blasted the Republican administration. To divert attention from the failings of leadership, the government played up stories of atrocities by the raiders, inflaming the public and laying the ground for further retaliation in kind.

BACK_TO_TOP* As might have been expected, in 1813 the naval war turned solidly against America. The humiliations of 1812 led to an outcry among the British public to deal with the insolent Americans, and so the Royal Navy presence in the western Atlantic was heavily reinforced. Under the direction of Admiral Warren, the blockade was tightened up along the East Coast to bottle up US Navy vessels and privateers, though New England remained exempt for the time being.

Even those raiders that managed to slip loose on moonless nights found the hunting more difficult, since the Royal Navy had set up convoys, with warships protecting groups of merchantmen. Privateering continued with considerable success, with raiders such SCOURGE, RATTLESNAKE, and TRUE-BLOODED YANKEE raising hell in Britain's oceanic backyard -- the YANKEE proving particularly effective, even burning seven vessels in a Scottish harbor. However, privateering was by no means as easy as it had been the year before: privateers usually tried to take prizes back to port, and thanks to Royal Navy vigilance, more often than not prizes taken by privateers were simply recaptured, in a few cases changing hands multiple times. Privateers increasingly decided to content themselves with capturing a ship, taking the most valuable loot off of it, then burning it.

US Navy warships still engaged in duels with Royal Navy warships on the high seas, with mixed results. On 24 February 1813 the sloop USS HORNET, under Captain James Lawrence, engaged the 18-gun Royal Navy sloop HMS PEACOCK off the mouth of the Demerara River in Guyana and defeated the British vessel after a short, nasty fight. Lawrence's luck ran out a few months later. On 30 April 1813, in response to a challenge from the captain of the blockader HMS SHANNON, Lawrence took the USS CHESAPEAKE out of Boston harbor to shoot it out -- and lost, being seized by the British after a battle that left the dead and wounded piled up on both sides. Britons felt that the Royal Navy had avenged the humiliations of the previous year. Lawrence was among the dead, his last words being reported as: "Don't give up the ship!"

It became something of an American battle cry, and Lawrence was played up as a hero -- Perry's flagship USS LAWRENCE was named after him and flew a war banner labeled with DON'T GIVE UP THE SHIP. However, Navy Secretary Jones then forbade his captains to accept such challenges -- Lawrence had been incompetent to snap at the bait in the first place, and had he not ended up a dead hero he might well have been court-martialed. In Britain, the defeat of the USS CHESAPEAKE was seen as avenging the humiliating defeat of the HMS GUERRIERE the year before, the victory being wildly played up as all but a "second Trafalgar".

Of necessity, the US Navy had to engage in hit-and-run tactics -- and in fact in early March, after encouragement by Navy Secretary Jones, Congress had authorized construction of six new 16-gun sloops similar to the USS WASP. Occasional confrontations between US Navy and Royal Navy ships continued, with mixed results for the Americans:

The Americans seemed to be holding their own, but only in an emotionally significant sense: even if the US Navy could take two Royal Navy warships for every American warship lost, that would still only result in the complete elimination of the US Navy, without real damage to the combat capability of the Royal Navy.

However, if the US Navy was no more than a nuisance on the high seas, the officers of the service were determined to make themselves as big a nuisance as possible. Captain David Porter of the USS ESSEX, hunting in the South Atlantic, felt he might do better in the Pacific, going through the Straits of Magellan to show up around the Galapagos in the spring. Among the crew was a pre-teen midshipman named David Farragut, who decades later would become the US Navy's first admiral. From the Galapagos, Porter began to hunt British whalers with such effectiveness that a whale oil shortage resulted in Britain, making lighting difficult. Late that year, after taking a number of prizes, Porter dropped anchor at Nuka Hiva in the Marquesas Islands to refit, resupply, and give his men some leisure time. In December, Porter got news that he was being hunted by the frigate HMS PHOEBE and the sloops CHERUB and RACOON; the odds didn't look so bad to Porter, so he departed towards Chile to look for action.

* As far as America's gunboat assets were concerned, Navy Secretary Jones found the little vessels frustrating and annoying, saying they were "scattered about in every creek and corner as receptacles of idleness and objects of waste and extravagance without utility." In March, Jones had shut down gunboat stations in locations where he judged them ineffective, and consolidated the survivors in a set of flotillas where they could provide more concentrated firepower and would be easier to control. Jones also managed to convince Congress to fund the construction of dozens of "gun barges", with one or two guns each, that could be shifted around as "floating batteries" to help protect vital harbors.

The gunboats did obtain some successes. On 9 October 1813, 26 gunboats fought it out with the Royal Navy frigate HMS ACASTA and sloop HMS ATALANTA in a stubborn brawl that ended only when weather intervened. On 13 November 1813, Royal Navy blockaders chased the merchantman SPARROW into shallow water, where the ship grounded; the British tried to seize her, but American gunboats intervened and drove them off, even seizing a British sloop. The gunboats might not have been any good in a stand-up fight, but they could make a damned nuisance of themselves.

The gunboats were effectively defensive weapons; some Americans had ideas for offensive weapons to be used against the blockaders. Robert Fulton, an inventor who had begun the first successful American commercial steamboat service in 1807 on the Hudson River, had a bent towards weapons and had unsuccessfully attempted to push concepts for "torpedoes" -- crude naval mines -- and man-powered submarines to the British and French some years previously. In 1813, Fulton returned to his experiments on torpedoes, attempting to use them against Royal Navy blockaders bottling up New York harbor.

There were others who thought torpedoes a good idea; in the spring, the government in Washington decided to offer a cash bounty to anyone who destroyed a British blockader, the bounty being proportional to the value of the target, and so developing torpedoes and similar dirty tricks became something of a cottage industry along the blockaded coast. The British acquired an exaggerated fear of torpedoes, becoming inclined to take reprisals against ports from which torpedoes were deployed. The Royal Navy's excitement over torpedoes seems to have been generated more by the malevolence of the concept -- they were seen as damned unsporting -- than by their effectiveness, which was negligible. The only real damage done was by a merchantman rigged as a floating bomb, and abandoned to a British blockader back in June 1813; the British put a prize crew on the merchantman, but the blockader had moved off when somebody tripped the bomb, sending the prize crew to the next world.

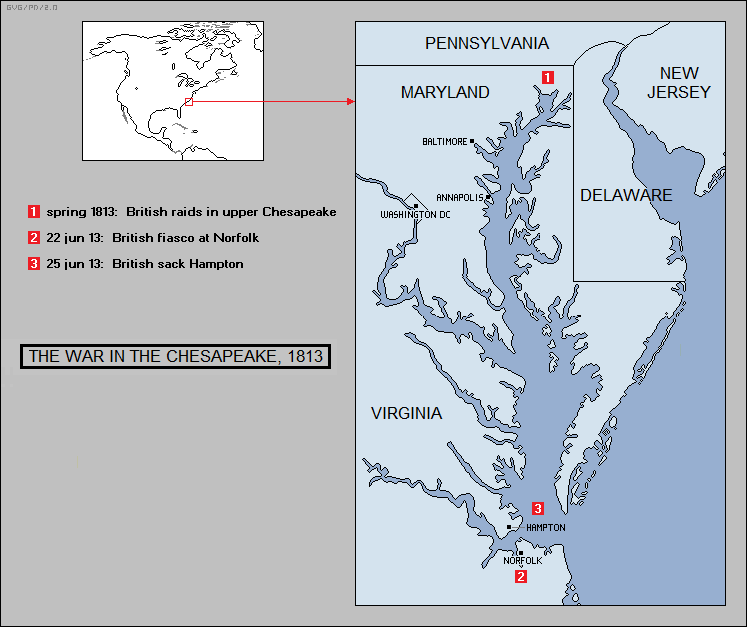

BACK_TO_TOP* With naval superiority established, from the spring of 1813 the British began coastal raids, focused on Chesapeake Bay. Admiral Warren sought "to chastise the Americans into submission" and relieve the pressure on British forces in Canada. The raids were delegated to Warren's second-in-command, Rear Admiral Sir George Cockburn -- pronounced "Coburn" -- with his forces targeting the upper Chesapeake Bay region from late April, burning buildings and ships at dock, with his men hauling off loot.

The Americans weren't able to do much to stop the British incursions, which only added to the public fury. A congressman reported: "On my way from Philadelphia to Washington, I found the whole country excited by these depredations. Cockburn's name was on every tongue, with various particulars of his incredibly coarse and blackguard misconduct." Cockburn's actions were actually restrained, with his men ordered not to molest unarmed civilians, no civilian structures destroyed unless they were used in battle, and provisions taken from civilians paid for -- if at knockdown prices set by the invaders, with payment in script that couldn't be redeemed until the war was over, if any of it ever was. One British lieutenant-colonel took no comfort in such cosmetic niceties, saying it was "hateful to see the poor Yankees robbed, and to be the robber ... you ruin a poor peasant if you take his only cow."

More amicably, the British often came ashore at coastal villages to buy provisions with hard currency, and Americans were perfectly willing to provide what they wanted; the King's gold was as good as any, and obtaining a profit was certainly preferable to being looted. Presumably for lack of any wiser policy, the government in Washington formally endorsed the practice. The British also encouraged American slaves to run away and join them, allowing them to enlist or accept relocation to the West Indies. The American government hardly approved of that practice, with observers noting how the British were provoking "loud houlings" from slave-owners. The British, who were generally antislavery, were entirely unsympathetic, one Royal Navy lieutenant commenting that the Republicans were "cruel masters" who would:

BEGIN QUOTE:

... grind and degrade those under them to the lowest stage of human wretchedness ... American liberty consists in oppressing the blacks beyond what other nations do, enacting laws to prevent their receiving instruction and working them worse than donkeys. "But you call this a free country when I can't shoot my nigger when I like -- eh?"

END QUOTE

In June, Warren joined Cockburn with reinforcements, with Warren deciding to attack the harbor of Norfolk in Virginia, in particular targeting the USS CONSTELLATION, which was anchored there. Norfolk's defenses rested chiefly on Craney Island, which guarded the narrow channel of the Elizabeth River. The island had a 7-gun fortification and was manned by 580 regulars and militia, in addition to 150 sailors and marines from the CONSTELLATION. The British planned to land a force on the mainland and, when low tide permitted, march against the flank of the defenses; when the tide rose, another force would be rowed across the shoals to perform a frontal assault.

On 22 June 1813, the landing party was put ashore, but the terrain made things very difficult for the attackers and they came under highly accurate fire from the CONSTELLATION's guns, being forced to withdraw. The frontal assault suffered much the same fate, with American guns sinking three barges and throwing the assault in confusion. After taking 81 casualties, the British sailed off in disorder, the defenders having suffered no casualties.

Frustrated at Norfolk, on 25 June the British crossed the inlet to Hampton and overwhelmed the 450 militia defenders, with British troops then running wild and trashing the town. A British officer proclaimed that "every horror was committed with impunity, rape, murder, pillage: and not a man was punished!" Of course the American press indignantly reported on the crimes, inflating them for good measure. The troops were actually French deserters in British uniforms, known as the "Canadian Chasseurs", and they were a wild lot who obeyed their officers only if they felt like it, or were forced to do so. Recognizing that they were troublesome, the British hauled them off to garrison Halifax -- where they persisted in their bad habits, raising "the greatest alarm" among the citizens.

Come September, the British gave up their attacks in order to rest and refit, Warren retiring to Halifax with prizes seized, Cockburn to Bermuda with his men. The British had enjoyed considerable success in their coastal raids in 1813, but they failed to divert American attention from Canada while helping to unify Americans against Britain. The blockade, however, was proving all expected of it, strangling American commerce; even coasting vessels were vulnerable, forcing goods to be shipped from state to state by way of a poorly developed road system. That meant American producers couldn't get their goods to American buyers, resulting in a wild pattern of gluts and shortages. Late in 1813, a panic set in, wildly driving up prices, though the speculative bubble popped early the next year.

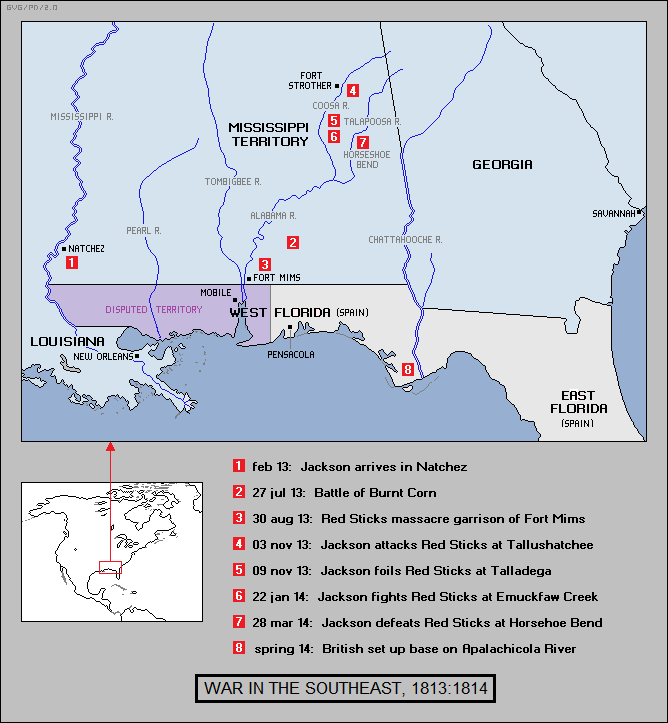

BACK_TO_TOP* There was fighting in the Mississippi Territory during 1813, though it only had an indirect relationship to the war against Britain -- being a conflict between white settlers and the Creek Indians, whose territory covered much of modern Alabama.

A fight had been brewing between the settlers and the Creeks even before the war had broken out. In May 1812, a band of Creeks had killed six settlers and kidnapped a woman named Martha Crowley. The incident, particularly the abduction of Mrs. Crowley, inflamed the citizens of the region, with the commander of the West Tennessee militia, Major General Andrew Jackson, calling up volunteers. Jackson was a tough, resourceful, and sharp-tempered frontiersman with an inclination towards the brute-force solution, and he believed the Creeks "must be punished". Incidentally, Mrs. Crowley eventually managed to escape her captors, and make her way to safety.

Tennessee's men were roused to join the fight, with many signing up with the militia. However, when Jackson received orders from the War Department in Washington late in 1812, he wasn't told to move against the Creeks; instead, he was directed to take his men south to New Orleans, where they could help defend the city and support moves against Spanish Florida. Getting organized took time, however, due to the difficulty of obtaining supplies for the expedition. The Federal government issued paper notes to support the expedition, but there was little confidence in them and they had no great purchasing power.

It wasn't until the first week of the new year that Jackson and his men set out from Nashville, floating on boats down the Cumberland -- a roundabout way to get to New Orleans, the river flowing north through Kentucky to the Ohio, and then down the Ohio to the Mississippi. The weather was variable, sometimes sunny, sometimes wintry and icy. The force finally made it to Natchez in mid-February, the bulk of their journey over -- or so they thought. On reaching Natchez, Jackson got a letter from General Wilkinson, at the time still in charge in New Orleans, telling Jackson to stay put with his men in Natchez.

Jackson had dealt with Wilkinson before and was suspicious of him, but Jackson did as he was told, putting his men to military drill in Natchez to keep them occupied. Then he got another letter, this one from War Secretary Armstrong, telling Jackson that the services of the militia were no longer needed -- the war against the British going badly, the government in Washington was less enthusiastic about operations against the Spanish in Florida. Jackson was told that the men should simply be released from service, to make their way back home as best they could.

Jackson was baffled and furious, since he was being told to abandon his men, including his sick and injured. The order was not only unconscionable, it would certainly destroy his credibility as a leader. Jackson marched his men back home; Wilkinson refused to provide funds for supplies for the march and so Jackson took the financial burden on himself, setting out with his men in late March. The movement went more swiftly than expected, the troops greatly wanting to get back home, with the citizens of Nashville coming out in force to greet the militiamen when they arrived in May. The force then disbanded.

Although Jackson was a militia officer with no formal military experience -- he had been elected to his position, effectively the only rank he had ever held was general -- his men found him admirable, describing him as "tough as hickory wood", giving him the nickname of "Old Hickory". Eventually, they would find out he demanded much more respect than they thought of giving him voluntarily.

* Come the summer of 1813, tensions with the Creeks escalated sharply. Tecumseh's trip to the South in 1811 had been inspirational to many Creeks, and they banded together to resist the settlers. These Creeks became known as "Red Sticks" after the war totems and war clubs they carried. One of the most prominent of the Red Stick leaders was a Creek chief named Red Eagle, or William Weatherford -- who was actually 7/8ths white, but had been raised Creek, was more militant than many fullbloods, and had established a strong leadership position among the renegades. Creek chiefs tried to restrain the Red Sticks, leading to a civil war in miniature among the tribes.

In July 1813, a group of Red Sticks went to Pensacola in Spanish Florida to trade for weapons to be used in the fight. On July 27, as the Red Sticks were returning, they were attacked by about 180 Mississippi militia; the Red Sticks lost most of their supplies in the fight, which was later named the Battle of Burnt Corn, but sent the militia packing, with the Red Sticks returning south to re-arm.

Now the fighting between the whites and the Red Sticks began in earnest. On 30 August the Red Sticks attacked Fort Mims, a day's ride north of Mobile; the defenders were unprepared for trouble, and though they killed many of the attackers, the Red Sticks overran the site, and slaughtered most of those there. A few whites did escape and spread tales of monstrous atrocities, which though exaggerated had a substantial basis in fact. The massacre at Fort Mims spread alarm through the region, with expeditions then raised by the whites against the tribes.

In late September, Jackson called up the militia again. He was not in the best condition for a campaign at the time, having been wounded after siding with one of his officers in a violent dispute; Jackson would have lost one of his arms, but he refused to let the doctors cut it off. He was still carrying the pistol ball around with him, along with another he had obtained from a duel in 1806. Modern analysis of Jackson's hair samples show he clearly suffered from lead poisoning as a result, contributing to his continuous health problems. However, Jackson was too tough-minded to allow his ailments to keep him out of the field -- though no doubt they aggravated his legendary explosions of rage.

On 10 October, Jackson put a force of 2,500 Tennessee militiamen on a march into Creek territory, looking for a fight. Jackson was to be reinforced by a second column of 1,500 East Tennessee militia under Major General John Cocke, while two other forces -- one consisting of Georgia militia under General John Floyd, the other of US Army regulars and Mississippi Territory militia under Brigadier General Ferdinand Claiborne -- were also to contribute to the campaign. The four forces were to move into Red Stick territory, destroy Red Stick villages, and set up a line of strongpoints to provide control over the region. Friendly Creeks and Cherokees -- the Cherokees wanted nothing to do with the Red Sticks -- assisted Jackson, providing scouting and intelligence.

Jackson moved his men south to the Coosa River, where he set up Fort Strother as an advance base. From there, his cavalry under the command of General John Coffee fought a battle at the Indian village of Tallushatchee on 3 November, with the militiamen bagging most of the defenders and slaughtering almost 200 of them. It was an ugly, butchering little fight; one of Jackson's scouts named David Crockett -- later a famous Texas frontiersman -- described how when he and his colleagues went against a house being used as a strongpoint by the defenders, an Indian woman appeared to come forward to surrender, only to put an arrow into and kill one of the attackers. Crockett said: "His death so enraged us all that she was fired on, and had at least twenty balls blown through her ... We now shot them like dogs; and then set the house on fire, and burned it up with the forty-six warriors in it."

Jackson reported to his superior, Tennessee Governor William Blount: "We have retaliated for the destruction of Fort Mims." Although Jackson's fierce reputation was deserved, he showed a different side by adopting a Creek boy named Lyncoya. Jackson sent the lad off to his wife, Rachel Jackson; the couple had no children of their own, but had already built up an adoptive family, and Lyncoya would be raised as if one of Jackson's own sons -- though the boy would die of pneumonia as a teenager.

Instructed by the example of what had happened to Tallushatchee, many Creek villages in the region declared their peace with Jackson. The general accepted their loyalty; William Weatherford was infuriated with the defections, and decided to destroy the village of Talladega in retaliation. Jackson got wind of Red Stick intentions, to march 2,000 men to Talladega, engaging about 1,100 Red Sticks on 9 November. He sent a force directly against the village, with instructions to make contact and then pull back, while cavalry and infantry columns advanced around each side of the village to seal it off. The Red Sticks fell into the trap, but managed to break out -- though not after losing about 300 killed, with Jackson losing only a handful. The Indians gave Jackson the name of "Sharp Knife".

That was effectively the end of the campaigning for the year. The force of East Tennesseans under General Cocke hadn't showed up, nor had any of the supplies that Jackson had expected arrived either, leaving him in a very difficult situation. His starving troops grew restless, all the more so because many of his militia believed they had stayed as long as they had signed up for. Jackson didn't agree with them; the militia counted their time in service as beginning when they went down the rivers to Natchez with Jackson, while Jackson insisted that the months during which they had been dismissed before being called up again didn't count. Cocke's force belatedly showed up at Fort Strother on 12 December, but they only made the supply situation worse, and the enlistments of the "reinforcements" were about to end as well. They were useless; Jackson told Cocke to march his men back to Tennessee and discharge them.

Jackson had to use threats to keep any of the troops around at all, but though he was a hard man, he was far from stupid, and the fact that he wasn't getting food supplies with anything resembling regularity made it very difficult to keep his men from leaving. How could he force them to stay to simply starve? Crockett wrote: "We were all likely to perish. The weather also began to get very cold; and our clothes were nearly worn out, and the horses getting feeble and very poor."

Jackson protested bitterly to the War Department and contractors over the failure to deliver food, but it did him little good, and he finally had to let the troops go. Incidentally, the force of Georgia militia under General Floyd had advanced into Red Stick territory from the east -- but on being given a serious bloodying by the Red Sticks, Floyd gave up the fight, withdrew, and discharged his men, with Georgia contributing little more to the war. General Claiborne's regulars and Mississippi militia similarly advanced from the south and made progress among the Red Sticks, but when the enlistments of his men gave up, desertions drained his force, and Claiborne had to give it up as well. All that was left of the war against the Red Sticks for the time being was Jackson and about 130 men still clinging on at Fort Strother.

BACK_TO_TOP