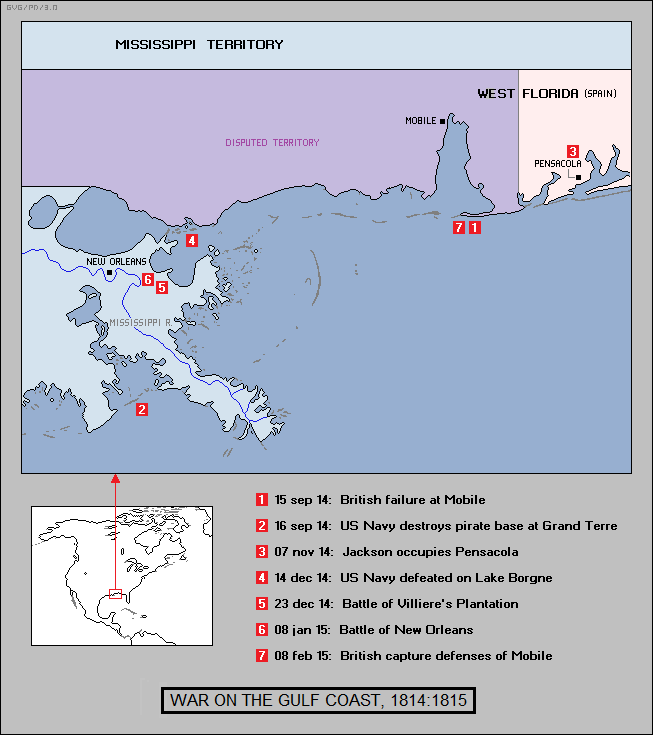

* Following the British rebuffs at Baltimore and Plattsburg, the war shifted focus to the Gulf Coast. Andrew Jackson had relocated to Mobile to deal with the threat, quickly taking action to block a British assault on Mobile and drive out the British presence in Spanish Pensacola. However, although few realized it -- least of all the Federalists, who met in Hartford, Connecticut, to organize their resistance to the conflict -- the war was in its final stages. The two negotiating teams in Ghent were able to come to an agreement, and in December signed a peace treaty. The treaty had to be ratified before it took effect, however, and in the meantime the struggle continued, with events building up towards a collision in front of New Orleans.

* After the rebuff at Baltimore, as mentioned the British fleet departed to the West Indies, to prepare for an attack on a new target: New Orleans.

The Mississippi River was a major path of communications through much of the center of the North American continent, and whoever controlled New Orleans had control over the Mississippi. As Jefferson had perceptively written in 1802 to Robert Livingston, the US ambassador to France: "There is on the globe one single spot, the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans, through which the produce of three-eighths of our territory must pass to market, and from its fertility it will ere long yield more than half of our whole produce and contain more than half our inhabitants."

Louisiana had originally been settled by the French, but it had been transferred to Spain in the 1760s as part of the fallout from the Seven Years' War. In 1800, Napoleon cut a secret deal with Spain to get it back; when the deal became public, Jefferson was alarmed, since it made France America's "natural enemy". Jefferson leaned toward France and against Britain, but the deal pushed the Americans towards the arms of the British, much against the instincts of the Republicans; in addition, taking military action to deal with the matter promised to be expensive. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 had relieved that problem for the Americans, but the British had never become all that reconciled to the deal -- the British questioned the legitimacy of anything Napoleon did, and they were also not at all pleased that the Americans had paid him $15 million for the territory, money that was then used to make war on Britain.

Given that many of the inhabitants of New Orleans and neighboring areas were French- or Spanish-speaking, there was valid reason to doubt they would fight for America with any enthusiasm -- and indeed, many of the non-English-speaking inhabitants of the city wanted nothing to do with America's war against the British. New Orleans looked like an easy target, made all the more attractive by the amount of loot that could be obtained from the city's warehouses. Once the British captured the city, their control over the mouth of the Mississippi would give them considerable bargaining power in the negotiations in Ghent. It was conceivable that it could even provide leverage to pry the Louisiana Territory away from the United States and block American expansion to the West, though that was taking a very ambitious read on matters.

* British activities in the Gulf region started to ramp up after the arrival of Cochrane in the West Indies, where his forces were to link up with troops hauled over from Spain. General Ross was actually supposed to have been in charge of the troops; following his death in action at Baltimore, the decision was made to replace him with Major General Sir Edward Pakenham. It would take time for Pakenham to cross the Atlantic, so in the meantime the troops were under the leadership of Major General John Keane.

Cochrane had been preparing the groundwork for actions in the Gulf well before his arrival there. In the spring of 1814, he had ordered Captain Hugh Pigot to proceed to Apalachicola Bay, in the middle of the Florida panhandle, and recruit disaffected Indians to the British cause. Pigot had arrived with two ships, the HMS ORPHEUS and HMS SHELBOURNE, on 11 May, finding many destitute Indians -- refugees from Andrew Jackson's war against the Red Sticks, eager to return to the fight with British arms and support. Later, the British moved up the Apalachicola River to build a fort at Prospect Bluff; come the summer, Cochrane sent Major Edward Nicholls of the Royal Marines with several hundred men to Prospect Bluff to organize the Indians there into a fighting force. Nicholls was supported by a squadron of Royal Navy vessels under Captain Sir William Percy.

Andrew Jackson was by no means unaware of what the British were doing in Florida, indeed he likely had an exaggerated fear of the threat they posed. The presence of the British in Florida was helpful to him, however, to the extent it helped promote the case for evicting the Spaniards from the land; he tried to use the reports of Indian activities there to give him a mandate from the War Department to move against the Spanish. Given how badly the war was going in general for the Americans at the time, few in the government thought it a good idea to get into a direct fight with Spain at the moment, and Jackson was told not to start a new war.

Jackson took a highly flexible view of his instructions, writing a stern message to the Spanish commander in Pensacola, Mateo Gonzalez Manrique, saying that warlike Indians had taken shelter in Spanish Florida with the permission of local authorities, with Jackson adding that his intelligence suggested the British were going to supply the Indians with arms. Jackson demanded that Spanish authorities cooperate with America in dealing with the Indians, and should not violate their neutrality by allowing the British to arm the Indians. Commandant Manrique shot back an angry reply.

Jackson's appraisal of British intent was entirely accurate. Alarmed by American threats, Commandant Manrique asked the British for help in defending Pensacola, with Captain Percy quickly hauling Major Nicholls and about a hundred of his men to the town, while several hundred Indians warriors marched in as well. The British arrived there on 14 August, with Nicholls taking charge of the defense of the area and also considering offensive actions.

The British were focused on Mobile at the time, seeing it rightly as vulnerable to capture. Once it had been captured, British forces could advance overland to Natchez; New Orleans, blockaded both from the Gulf and upriver, would then certainly fall. Jackson understood this perfectly well, and so he went south to Mobile to confront the threat, arriving there on 22 August. The first thing he did on arriving was to order Major William Lawrence to take a small force to Fort Bowyer, on the sandspit at the entrance to Mobile Bay, and get it into fighting condition. The fort was in poor condition and wasn't particularly impressive, but Lawrence skillfully put matters right, fitting it with 20 guns.

BACK_TO_TOP* In the meantime, the British were investigating other opportunities for making trouble in the Gulf, with Nicholls issuing a proclamation encouraging the "Spaniards, Frenchmen, Italians, and British" of Louisiana to abolish the "American usurpation" of the land, casting off the "faithless, imbecile government" in Washington. To help distribute the message, the British contacted Jean Lafitte -- sometimes spelled "Laffite" -- who was the boss of a big gang of pirates who resided in Barataria Bay, to the west of the Mississippi Delta.

The Baratarian pirates weren't really any vicious gang of cutthroats; they were essentially in business on the edge of the law, engaged in smuggling, particularly of slaves, and in privateering against Spain on behalf of emerging independent Latin American states. They did well at their business, with New Orleans enriched by their activities, and there were many prominent citizens of Louisiana who found dealings with the pirates profitable enough to decide to look the other way. However, in 1814 the American authorities decided to not look the other way, with Louisiana Governor William Claiborne putting a price of $500 on Lafitte's head. Lafitte put a price of $1,000 on the governor's head in return -- it seems as a gag, Lafitte having a showy personal style.

The Royal Navy sloop HMS SOPHIE, under the command of Captain Nicholas Lockyer, came to the pirate base on Grand Terre island in Barataria Bay in early September, with British officers going ashore to talk to Lafitte, asking him to distribute Nicholl's proclamation. They also had a personal message written by Admiral Percy for Lafitte, the letter indicating that the British wanted him to sign up and support their cause, offering him a commission in the Royal Navy and 30,000 pounds in hard currency if he did so. They added that he would be sorry -- "war instantly destructive" was the phrase used -- if he didn't. That put Lafitte between a rock and a hard place, since the news of what General Jackson had done to the Creeks strongly suggested that if the pirates signed up with the British and the British didn't prevail, the pirates would suffer "war instantly destructive" anyway. The British gave him two weeks to think it over.

In essence, Lafitte had to gamble his future on which side he thought would win the war -- a calculation influenced by the fact that if the British prevailed, the Royal Navy would very likely suppress piracy in the Caribbean, putting the Baratarian pirates out of business. He was in a difficult position, but one that offered a degree of leverage as well: Lafitte sent a message to Governor Claiborne, reporting the discussions with the British, offering to side with the US government, and asking the governor for amnesty for him and his men if they did. Claiborne was not swayed, and in fact the authorities escalated their actions against Lafitte, with the US Navy commander in New Orleans, Commodore Daniel Patterson, ordered to move on Barataria Bay and clean out the pirates.

Patterson commanded a force of 15 vessels, the largest being two schooners, the USS CAROLINA -- with 14 guns -- and the USS LOUISIANA -- with 16 guns. The rest of the squadron included a few smaller schooners, a half dozen gunboats, and a number of miscellaneous vessels. He left dock on 13 September, to descend on Grand Terre on 16 September. Lafitte and most of the pirates managed to get away, but Patterson captured 80 of them, along with eight of their vessels and a pile of loot. Patterson torched whatever was left behind, and so when Captain Lockyer returned to get Lafitte's answer to the British proposal, he found only a burned and deserted village. The one silver lining for Lafitte was that British threats against him had been rendered null and void; the pirate's quandary had been resolved.

BACK_TO_TOP* The British also moved against Mobile, with a force of Royal Marines and Indians being taken there by Percy's ships, arriving on 15 September. That afternoon, the British warships began to pound Fort Bowyer; since they had almost four times as many guns, they had good reason to think they could pound it into submission. However, thanks to a lack of cooperation from the winds the vessels couldn't get into position to deliver effective fire, ending up trying to do the best they could from anchor. After an hour of shooting, the fort shot away the anchor chain of the HMS HERMES, which drifted towards the American guns and was given a terrible smashing-up. The crew abandoned and torched the ship, which finally blew up when the flames reached its magazine.

The British realized they were playing a losing game and left. The little battle had resulted in dozens of British casualties, but only a handful of Americans killed and wounded. Jackson was pleased at the repulse of the British, but not so pleased at the strong role luck had played in the engagement. He couldn't rely on staying lucky, and in fact he was expecting the British to return to Mobile at any time.

However, having failed to bypass New Orleans by capturing Mobile, New Orleans had become by default the primary British target in the Gulf. Jackson had received a message from a New Orleans "committee of safety", the letter pointing out that the numbers of white folk available to defend the city had their hands full trying to keep the large slave population under control in the face of British attempts at subversion, and begging Jackson for assistance. Jackson appreciated the threat to New Orleans, but he was not happy for the locals to tell him up-front that they couldn't be counted on to help.

For the moment, Jackson's preoccupation remained Pensacola. Since Pensacola was a neutral port, American ships had access to the place, and ship captains reported the presence of the British there to Jackson -- who properly reasoned that the British in Pensacola had violated Spanish neutrality, giving him cause to move against the town. That would be in violation of his orders from Washington; he wrote a letter to acting War Secretary Monroe in which he justified the operation, and then went forward, on the assumption that if successful, he would suffer no harm.

The very day he moved out, 25 October, Monroe sent off a letter ordering Jackson to do nothing to provoke a fight with Spain. Monroe had been in no hurry to send off such orders; some historians suspected later that the government in Washington tacitly approved of an invasion of Spanish soil, but wanted to avoid official complicity in it. On the other hand, the war had demonstrated to that time that the organization of the government in Washington left something to be desired, and destruction inflicted on the city in August could have hardly made the government more responsive.

Jackson's force included Army regulars, Tennessee and Mississippi militiamen, and a band of Choctaw Indians. Jackson arrived at the outskirts of Pensacola on the evening of 6 November 1814. The town was protected by two small forts, Fort Saint Rose and Fort Saint Michael, with the entrance to Mobile Bay protected by a more substantial installation, Fort Barrancas. Jackson sent a message to Commandant Manrique, saying that American forces were going to occupy the town and that no harm would come to the defenders if they didn't resist, but that the Spanish authorities would need to hand over Fort Barrancas "until Spain can preserve unimpaired her neutral character." The messenger carrying the note from Jackson was fired on; Jackson wrote a second note and had a Spanish prisoner released to carry it to Manrique.

Manrique refused the demand and so the next day, 7 November, Jackson threw in his troops, overwhelming the town's defenders quickly and with little bloodshed. Manrique surrendered. Fort Barrancas did not give up immediately, and Jackson prepared to assault it the following morning -- but Major Nicholls blew up the fort, with the British evacuating, to go back out to sea. The destruction of Fort Barrancas suited Jackson fine, since he had no intention of holding Pensacola or had resources to do it; he simply wanted the place disarmed, and the Spanish suitably intimidated.

It was smartly done, Jackson having caught the British in Pensacola completely flat-footed, doing much to ensure that the British couldn't expect real help from the Spanish in Florida in the future. While in Pensacola he learned that the British were planning to move against New Orleans, so he returned control of Pensacola to Manrique in a polite ceremony, to put his men on a march west, returning to Mobile; then setting out to New Orleans on 22 November with 2,000 men, leaving behind the remainder of his force in Mobile under General James Winchester to counter any British attempt to take the town again.

BACK_TO_TOP* The action on the Gulf Coast didn't make much of an impression on the overall gloom many Americans felt over the war. After discussions among New England Federalists and state governments from early in 1814, in November the Federalists set up a convention in Hartford, Connecticut, to discuss their unhappiness with the status quo and what to do about it. The fact that the proceedings were kept secret raised enormous suspicions in the government, which took preliminary steps to deal with the prospect of New England seceding from the Union.

They need not have worried so much. There were hotheads among the Federalists at Hartford, but they didn't carry the day, with moderates able to retain control of the proceedings. The consensus was an agenda for Federalists to work for redress of their grievances on the national and regional level within the context of the law; if that didn't work, the door was left unlocked for more extreme measures. The Hartford Convention seemed much more treasonous than it actually was; one Federalist, unimpressed with the proceedings, said that the only result would be "a GREAT PAMPHLET!"

* Even as they were completing their deliberations in Hartford, the British and American peace commissions were finally, after months of delay and deadlock, moving swiftly towards a deal. In November, Lord Liverpool had informed Lord Castlereagh, the foreign minister, that it was time for Britain to wash its hands of the American quagmire: "I think we have determined, if all other points are satisfactorily settled, not to continue the war for the purpose of obtaining or securing any acquisition of territory."

The Americans were in no position to press demands, the British were making no demands in return, and so all that was left to discuss was fine print. In the end, nothing was said about impressment, though with the end of the Napoleonic Wars the American commissioners were privately reassured that they needed to fear nothing on that score; however, the British didn't rule out restoring the practice if they saw the need. There were still border issues to work out, but those were delegated to postwar commissions set up by agreement between both sides, with both sides to abide by the decisions of the commissions.

The American negotiators were not happy about what Clay called "a damned bad treaty", Clay believing that they would "all be subject to much reproach." However, it was far better than defeat, and so the Treaty of Ghent was signed on 24 December 1814. It did not mean the war was over, since the treaty was not to take effect until it had been ratified. Given the sluggish nature of international communications in those days, that was not going to happen overnight, and in the meantime the fighting would continue.

BACK_TO_TOP* Andrew Jackson arrived in New Orleans with his force on 1 December 1814. He had been warned that many of the people of the city were of doubtful loyalty, and on arriving discovered it was all too true. Jackson issued a proclamation to the citizens, saying he had learned that "great consternation and alarm pervade your city", admitting that the city was indeed threatened by the British but that Americans would "beat them at any point" if the "common enemy of mankind, the highway robber of the world" dared attack. He also made it clear in detail that a failure to cooperate with the defense would be unwise: "Those who are not with us are against us, and will be dealt with accordingly."

The seriousness of the British threat became apparent soon after Jackson's arrival. A direct assault on the city up the Mississippi was problematic, it being difficult to take large vessels upstream in the age of sail; the winding bends of the river made it all the more difficult, with the bends proving excellent positions to set up strongpoints with artillery to command the river. Two forts, Fort Saint Philip and Fort Bourbon, presented significant obstacles to a move upriver.

There were other approaches to New Orleans, of course. Lake Borgne -- actually an oceanic bay at the southeast corner of Louisiana -- offered a place to set off troops to attack the city from the east, while Lake Ponchartain, which links into Lake Borgne, gave access to the city from the north. Both bodies of water were shallow, however, meaning they were only navigable by shallow-draft vessels; the British chose to attack by way of Lake Borgne, with a force of 14,000 troops supported by Royal Navy warships, transports, and auxiliary vessels.

From 10 December, British gun barges and gunboats conducted running clashes with five of Commodore Patterson's gunboats, under the tactical direction of US Navy Lieutenant Thomas ap Catesby Jones -- the puzzling name was Welsh, meaning "Thomas son of Catesby Jones". Jones was unable to do more than harass the British, however, and was finally forced to stand and fight by uncooperative winds and tides on 14 December. The result was a sharp, nasty battle against a British force of over 40 armed ship's boats, in which Jones was wounded and all the American gunboats taken. The failure of American arms in the "Battle of Lake Borgne", as it came to be known, greatly agitated the citizens of New Orleans. Jackson, who took a very dim view of public unrest, responded by declaring martial law over the city on 16 December; it was questionable that he had the formal authority to do any such thing, but Jackson was never one to worry overmuch about formalities. Movements in and out of the city were to be supervised, and a strict curfew was imposed.

Jackson also called up the local militia -- though they were a motley bunch, widely diverse in ethnicity, social class, and level of motivation. Jackson put them to drill in hopes of making something out of them, since he needed all the help he could get, and particularly praised the black militia units. On 17 December, he also agreed to bring Jean Lafitte and his pirates into his force, granting the amnesty that Lafitte had asked for, in return for loyal service.

Jackson hadn't wanted anything to do with them, referring to them as "hellish banditti"; the pirates were violating American neutrality by preying on vessels of nations not at war with the United States, and even Jackson was aware that he couldn't lash out at the Spanish for violating their neutrality while condoning violations of Spanish neutrality himself. However, Governor Claiborne had come around to believing Lafitte's help was necessary; Claiborne was persuasive, with Jean Lafitte also performing a smooth sales job on the general. The pirates were skilled gunners, and so Jackson set them up in artillery units to contribute to the defense of the city. Lafitte himself returned to Grand Terre to keep an eye out for any British moves from that direction.

In the meantime, the British fleet had been offloading troops using barges, ferrying them to the Louisiana shores. The attractions of the Lake Borgne route were balanced by the fact that British troops had to advance over treacherous terrain, marked by marshes, swamps, and watercourses -- with General Keane's shortage of flatboats making things even more difficult for him. British troops found the alligators that infested the area particularly intimidating. On top of that, the weather was unusually chilly for the Gulf Coast, with frosts in the morning and some of the black troops in the British command dying of cold and exposure.

The British reached the Mississippi just south of New Orleans on 23 December. Keane decided to halt for the moment at the plantation of one Jacques Villere; one of Villere's sons managed to get away and give warning that afternoon. Jackson responded promptly, later explaining to James Monroe: "Perfectly convinced of the importance of impressing an invading enemy in the first moment of his approach with an idea of spirited resistance, I lost no time in making preparations to attack him that night."

Jackson marched about 1,500 men to confront the invaders. After sundown, the USS CAROLINA moved down the Mississippi under the cover of the dim light, the ship's gunners then enthusiastically hammering the British with her guns -- much to the surprise and excitement of the British soldiers in the camp. One British officer remembered "flash, flash, flash came from the river; the roar of cannon followed, and the light of her own broadside displayed to us an enemy's vessel at anchor near the opposite bank, and pouring a perfect shower of grape and round shot, into the camp."

Jackson's men moved forward along with the CAROLINA's bombardment, resulting in a mad artless brawl in the dark, with friendlies firing on friendlies. The fighting lasted well into the night, the Americans pulling back north before daylight the next morning -- which was fortunate, since Keane had received the reinforcements he'd been waiting for, and could have crushed Jackson. As it was, the "Battle of Villere's Plantation" had no particularly specific result other than to kill and wound hundreds of men on both sides, and both claimed the win. Jackson had much better cause to crow, having demonstrated to the British that their campaign to capture New Orleans was not going to be a walk-in.

In fact, if the British had immediately returned to the offensive, they would have stood a good chance of brushing aside Jackson's awkward little army and taking New Orleans -- but Jackson's aggressiveness had made them cautious, disinclined to take the risk. Jackson, incidentally, later said that if the British had pushed him out of New Orleans, he would have torched the city behind him and then blockaded the river to isolate the invaders. Jackson's professional skills as a general were imperfect, but he had an instinctive understanding of war, and the ruthlessness to do whatever he thought he needed to do to win.

* General Pakenham finally arrived on Christmas Day to take charge of the British force. Pakenham, the Duke of Wellington's brother-in-law, was highly regarded by the troops and other officers for his courageousness and sensibility, if not his imagination. Wellington had commented of him: "Pakenham might not have been the brightest genius, but my partiality for him does not lead me astray when I tell you he is one of the best we have." The troops greeted him with artillery salutes. Pakenham carried a royal commission as governor of Louisiana in his kit, though of course that was nothing more than a scrap of paper unless he could defeat Jackson.

Pakenham felt confident of doing so; Jackson was determined to prove Pakenham wrong. The Mississippi, in its endless twists and turns, flows eastward at New Orleans, with the city having grown up on the north bank of the river. Constrained by the swampy terrain, the British force had only one avenue of approach; Jackson chose an old canal cutting across the northern line of advance for his defensive line, setting his men to making the ditch wider and deeper while building up breastworks behind it. He set up his headquarters in a house a few hundred yards behind the line. As a precaution, work proceeded in parallel on two fallback defensive lines.

In the meantime, the US Navy continued to attack the British, with the LOUISIANA joining the CAROLINA in taking pot-shots from the river into the invader's encampment. Although the bombardment wasn't very effective, it was damned annoying, and Pakenham quickly got tired of it. He had a battery of guns set up on a levee, which managed to destroy the CAROLINA with hot shot on 27 December, fire setting off the ship's magazine. Most of her crew had escaped before the explosion, and some guns were also salvaged from the wreckage. The LOUISIANA was towed out of range by small boats.

Pakenham's men advanced on Jackson's line on 28 December, in the belief that a show of force would drive off the defenders. It didn't work; the defensive line was well chosen, with a deep and open field of fire in front of it, and before the British had advanced very far they came under heavy cannon fire. The LOUISIANA contributed to the bombardment, with the ship's gunners energetically hammering the assault with hundreds of rounds of shot and shell. The British advance was immediately halted and thrown back. Obviously, more earnest effort would be needed to defeat Jackson's men.

The LOUISIANA withdrew back to New Orleans. There Commodore Patterson set up a defensive line on the far bank of the river, borrowing guns from the LOUISIANA to arm it and using his sailors to man it, with Louisiana militia providing support for the sailors.

BACK_TO_TOP