* In the late 1960s, the spacesuit came of age, with the Americans developing the "A7L" suit for the Apollo Moon program, and the Soviets developing the "Sokol" suits for their Salyut space station program. Later suits would be improvements or follow-ons to these designs -- though a new generation of suits is now emerging.

* There were 11 crewed Apollo flights from "Apollo 7" in 1968, an Earth-orbit mission, through "Apollo 11" in 1969, the first Moon landing, to "Apollo 17" in 1972, the last of the six Moon landings. There had been tinkerings with various Moon suit designs since the Apollo program had begun in 1961, some of the concepts being thoroughly wild.

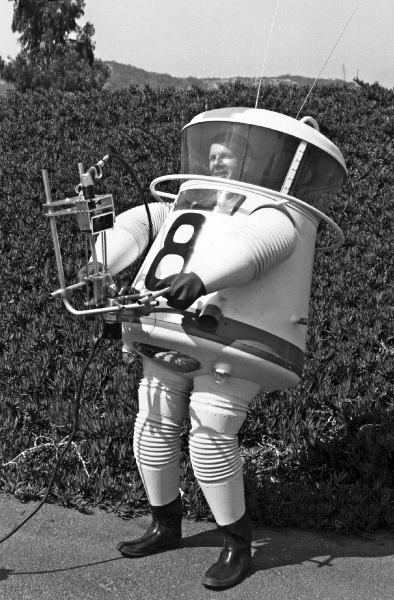

One that got quite a bit of press in the early 1960s was the "keg on legs" spacesuit from Grumman, which was a metal can with spacesuit arms and legs. It was entirely dubious in appearance, and it seems just as worthless in practice; NASA was not impressed, and in hindsight the Grumman suit appears to have been little more than a publicity stunt. Another "keg on legs" suit from Republic Aviation, this item resembling an oil barrel with a domed top, arms and legs being tacked on, was even more dubious.

More seriously, NASA also explored a series of "rigid" Moon suits, something like a suit of medieval armor in plastic, such as the "RX" series developed by Litton. The rigid suits never flew. Apollo early test flights were supposed to use slightly updated DCC G4C suits; however, due to delays, these suits were used for training early on, but never flown on an Apollo capsule.

NASA conducted a lengthy competition to obtain a suit for Apollo, finally selecting a team of ILC and Hamilton Standard in 1965. The refined version of that suit, the "A7L", was a marvel of engineering, designed to operate over an extreme range of temperatures. As with the David Clark G4C suit, the A7L came in IVA and EVA configurations. The A7L was entered from the back, using a sealing zipper scheme to close up the suit, and featured three garments:

The suit featured accordion-style joints, and was generously fitted with pockets and straps for hauling around small items. Boots were built into the suit; there were sealing connection rings for gloves and helmet attached to the TLSA. An astronaut put on a "Communications Carrier Assembly" AKA "snoopy cap" with mikes and earphones before snugging on the helmet, which was an all-transparent polycarbonate plastic bubble that snapped into the neck ring. NASA hadn't been particularly happy with the fact that earlier operational suits had visors that could open -- one more thing to go dangerously wrong -- and felt the one-piece bubble helmet was the better way to go.

The IVA suits were only used on takeoff and re-entry, the Apollo crew changing to coveralls in mid-flight. The EVA configuration featured a number of accessories:

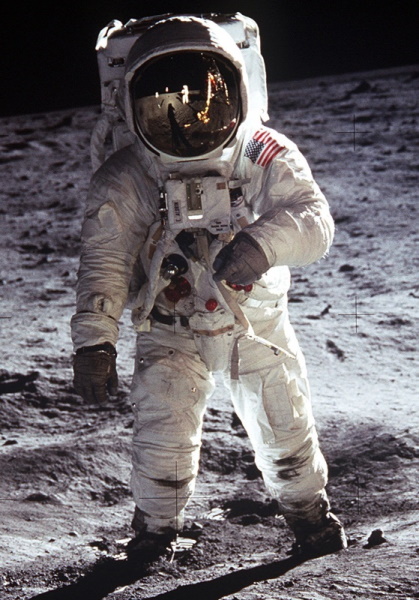

The A7L featured pockets and a "cuff checklist" to allow the astronaut to track activities. The A7L suit itself weighed 22 kilograms (48 pounds), while the PLSS backpack weighed 26 kilograms (57 pounds). The suit could maintain its wearer in temperatures ranging from -180 to +155 degrees Celsius (-290 to +310 degrees Fahrenheit). The A7L suits were custom-fitted to each astronaut, with three made for an astronaut -- one for training, one for flight, one for flight backup.

The suit was necessarily clumsy, but astronauts who went to the Moon found it surprisingly easy to move around in a sixth of the Earth's gravity. One significant problem was that lunar dust was charcoal-like and tended to smudge the suits badly, which was not just unsightly -- it made them prone to solar overheating.

Later Apollo Moon flights allowed the astronauts to ride an electrically-powered "Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV)", or "Moon Buggy"; the A7L wasn't designed for sitting, so a modified "A7LB" suit was introduced that was compatible with Moon Buggy tripping. Changes consisted mostly of moving zippers and connectors around, with a consequence that the A7LB was somewhat heavier than the A7L.

The Apollo Moon flights were followed by the "Skylab" space station flights. Skylab was a modified Saturn V upper stage, put into orbit in May 1973, with three visits by astronauts, using the Apollo capsule for transit, through the rest of the year. Skylab accommodations were downright luxurious compared to every other spacecraft flown to that time, with the astronauts provided with private sleep stations, exercise gear, a workable zero-gravity toilet, and even a wipe-down "shower" stall.

Skylab astronauts wore modified versions of the A7LB suit for station operations, featuring a thinner ITMG protection layer to reduce weight, the level of protection required not being as great as on the Moon. For EVA, the Skylab A7LB suits also featured a simplified helmet-visor assembly, plus an umbilical for oxygen and cooling water supply, a self-contained system being seen as more cumbersome. The suit had a half-hour backup oxygen supply in case the umbilical was blocked or broken.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Soviets actually beat the US in lofting a space station, sending up lofting "Salyut 1" in mid-April 1971. The Soyuz was to be used for transit with the Salyut space stations; the "shirtsleeve" environment used on early Soyuz flights was initially retained for the Salyut program, the airlock system on the Soyuz being updated so that no space suit such as the Yastreb was required. That policy led to disaster.

The first Soyuz mission to Salyut 1, "Soyuz 10", failed to dock; the second, "Soyuz 11", docked successfully, with cosmonauts Georgiy Dobrovolsky, Viktor Patsayev, and Vladislav Volkov spending almost 24 days in orbit. On the return to Earth of Soyuz 11 on 30 June 1971, the re-entry module lost pressure at high altitude, killing the three cosmonauts. Soyuz flights were halted while Zvezda was tasked with developing an IVA suit as fast as possible that would require the least modification of the Soyuz capsule.

Zvezda had designed an improved military pressure suit, the "Sokol (Falcon)", and modified it as a space rescue suit, with the result designated "Sokol-K", the "K" essentially standing for "kosmos / space". Considerable revisions were required from the original Sokol, such as a new helmet; in the final product, the cosmonaut wore cotton long underwear, covered by a lined pressure garment, and then a cover / restraint garment. The boots and helmet were integral, with a communications cap worn under the helmet; the gloves were connected by locking rings. The Sokol-K suit obtained air or oxygen -- there were separate lines for the two -- from the spacecraft. It was very lightweight, only 10 kilograms (22 pounds).

Since the Soyuz didn't use ejections seats, the Sokol-K didn't feature any provisions for parachuting; a separate survival kit was provided for dealing with conditions after touchdown, with the kit including a survival garment that would be worn in place of the Sokol-K suit. In addition, it included from 1986 a survival weapon, the "TOZ-92 / TP-82", which looked a bit like a sawed-off break-open double-barreled shotgun -- a scaled-down one, with bores of 12.5 millimeters (32 gauge), also useful as a flare gun -- but with a pistol grip. Along with the twin shotgun barrels, it had a rifle barrel between and below the shotgun barrels, firing a 5.45x39-millimeter round, the same as used by the AK-74 assault rifle; and featured a buttstock that could be clipped on to the base of the handgrip -- the buttstock being useful as a machete / tool when the canvas cover was removed.

In any case, initial flight service of the Sokol-K suit was on "Soyuz 12", launched in September 1973, with cosmonauts Lazarev and Makarov on board. There was no way to quickly adapt the Soyuz capsule to handle three cosmonauts wearing IVA suits, so for the time being, Soyuz flights only handled two crew. The Soyuz capsule was eventually remodeled to handle three crew with Sokol suits.

The Sokol-K suit proved satisfactory, but it was a rush job and left something to be desired. Its fit was not particularly comfortable, particularly under the knees; it was hard to put on and take off unassisted; and the downward view out the helmet was poor. Work went forward on improved suits, first the "Sokol-KM", followed by the "Sokol-KV", both of which were experimental, and then the operational "Sokol-KV2" suit, introduced in 1980 and still the standard Russian IVA suit.

The Sokol-KV2 was easier to put on and take off -- it added a distinctive "vee" arrangement of two zippers up front. The traditional rubberized pressure garment was replaced by one using a more modern polymer; it also featured a bigger helmet with a better field of view, along with some other tweaks. The Sokol-KM and -KV suits had featured a liquid cooling undergarment, but that was judged overkill, and not included with the Sokol-KV2.

Chinese Shenzhou "taikonauts" obtained a version of the Sokol-KV2. An experimental "Strizh (Swift)" IVA suit was also developed for the Soviet Buran shuttle program of the 1980s -- of heavier construction than the Sokol, since it had to support high-altitude ejection. Buran never flew a crew, and the Strizh was abandoned.

* In 1972, the redundancy of the Navy and Air Force pressure suit programs led the Pentagon to hand the "charter" for work in the field to the Air Force, with the USAF "Life Support Special Project Office (LSPRO)" assigned to do the work; the Naval Air Development Center maintained a liaison officer at LSPRO to make sure Navy interests were considered. The Navy then abandoned their Mark IV-type suits and adopted Air Force suits.

The David Clark Corporation was the beneficiary of this consolidation, obtaining a monopoly of sorts on the supply of US military pressure suits. While the Air Force had focused on the DCC MC-2 suit and its derivatives in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the company was working in parallel on another series of pressure suits, with the initial customer being the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) for the CIA Lockheed A-12 Archangel high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft. The result was the "Pilot's Protective Assembly (PPA) Model S901". This led to the "S1010 PPA" of the mid-1960s for the Lockheed U-2R spyplane program, and the S1024 AKA A/P22S-6 suits mentioned earlier.

In the 1970s, DCC evolved the design to the "S1030" suit for the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird, the Air Force version of the A-12. An improved "S1031 PPA" was also introduced for the U-2R. The Air Force finally decided to acquire a common suit for the SR-71 and U-2R, and in the early 1980s obtained the "S1031C" that could be used in both aircraft. Refinement continued, leading to the "S1034 PPA", introduced in the early 1990s, and at last notice still service standard.

The David Clark S1030C of the early 1980s provides a baseline for description of this family of pressure suits. The S1030C was a precision-built garment with a weight of about 16 kilograms (35 pounds) and was available in twelve standard sizes. It featured seven garment assemblies, including:

The helmet had an internal sizing and fitting system, originally developed by the Navy in full pressure suit developments of the late 1950s. It had both clear and tinted visors; ports were included in the chin area to permit ingestion of food and fluids from aluminum squeeze tubes. It took about 45 minutes to don the suit, with the help of two techs; successor suit designs were easier to put on. Other enhancements in later suits include improved urine collection systems, and a seawater-activated automatic life preserver system.

These military pressure suits were the basis for the IVA suits used on the NASA space shuttle. For the first four shuttle flights, the crew wore the David Clark "S1030A" AKA "Ejection Escape Suit (EES)", much like the suits worn by Air Force pilots flying the SR-71 Blackbird, and sat on Lockheed-built ejection seats derived from the SR-71's SR-1 ejection seat. The suits and ejection seats were useful only at relatively low altitude and speed.

Following the shakedown flights, the crews wore no special protective garments, taking off and landing wearing NASA blue flight coveralls and a DCC "Launch Entry Helmet (LEH)". The LEH was effectively a US Navy HGU-20/P helmet -- which looked like a full pressure helmet, but wasn't, merely providing oxygen through a face mask, along with crash and fire protection.

Following the loss of shuttle Challenger / STS-51-L after launch in 1986, NASA decided to restore use of pressure suits, initiating a "fast track" program with the David Clark Corporation to obtain a solution. The result was the "S1032 Launch Entry Suit (LES)", which was a partial pressure suit to provide anti-gee protection, emergency pressurization, anti-exposure protection, high altitude escape, and sea-survival for shuttle orbiter crews. The LES featured an integrated parachute, emergency oxygen system, and survival kit pack, worn on the back. Although early LES suits were blue, NASA soon standardized on bright orange.

In the mid-1990s, the LES was replaced with the improved David Clark "S1035 Advanced Crew Escape Suit (ACES), a full pressure suit with tech derived from the USAF David Clark "S1034 Advanced Lightweight Pressure Suit (APLS)". ACES only provided life support for ten minutes. Total weight of the ACES suit was 42 kilograms (92 pounds), including parachute, survival kit with flotation device, and life-support systems.

NASA is working on an "Artemis" program for crewed lunar exploration, with the work including space suits. NASA is introducing an "S1041 Orion Crew Survival System (OCSS)", which will be an improved derivative of the S1035 ACES suit. It features enhancements such as improved avionics, updated footwear, and a redesigned helmet.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Soviets worked towards a crewed Moon landing in parallel with Apollo, with two cosmonauts to travel to the Moon and one to land; of course, they required spacesuits to support that mission. Preliminary work had taken place from 1960 on the "SKV" suit -- that being a Russian acronym for "EVA suit" -- which was a semi-rigid suit, being built around a "hard upper torso (HUT)" made of fiberglass to which soft pants, arms, and a helmet were attached. The cosmonaut clambered into the suit through a door in the back of the HUT.

SKV was a purely experimental suit. Formal work on a derivative Moon suit, named "Krechet (Gyrfalcon)", was initiated in 1966, with the HUT being made of lighter aluminum alloy, leading to the "Krechet-94" production version. Parallel work was done on a soft Moon suit, the "Oriol (Eagle)" -- as well as an "Orlan (Sea Eagle)" soft suit for the mission commander, who wouldn't land on the Moon. The Moon suits demanded ten hours of operation; better thermal protection; better cooling, dictating a water-cooled liner; and provisions for water and sanitation. The Krechet-94 suit was much preferred to the Oriol soft suit, which was only being developed as a backup.

The Orlan suit had elements in common with the Kretchet-94; it was not designed as an IVA suit, instead as a lightweight EVA suit, with a total weight of 59 kilograms (130 pounds). It only had an endurance of 2.5 hours; it also had lighter thermal insulation, and no provisions for water and sanitation. It had a self-contained air supply, but featured a power umbilical / tether. It did not have to be custom-built for each wearer, instead featuring elements that allowed it to be adjusted to build within a range of body sizes.

Soviet cosmonauts would never get close to the Moon, and so the Krechet and Oriol Moon suits as such would never be used. The Orlan suit, however, did undergo further development, being improved for the Soviet space station program, emerging as the "Orlan-D" suit, which went into service in 1977. It featured a HUT and a liquid cooling garment; thermal-micrometeoroid protection layers; a helmet with glare and UV protection visors; plus a 20-meter (66-foot) tether / umbilical to provide electrical power and communications. Weight was 73.5 kilograms (162 pounds). It could support EVA activity for up to 5 hours.

The Orlan-D was followed by successively improved derivatives:

Several Orlan variants were designed for training as well. The Orlan-M/MK suit remains the standard Russian EVA suit. It was also used as the basis for the joint European-Russian "EVA SUIT 2000", intended for the European Space Agency's Hermes spaceplane, though EVA SUIT 2000 was canceled along with the Hermes program. The Chinese have used the Orlan-M/MK EVA suit on their crewed spaceflights as well -- calling it the "Haiyang", Chinese for "sea eagle".

An EVA suit was developed for the shuttle program, in the form of the "Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU)" suit. The EMU was based on a "Space Suit Assembly (SSA)" built by ILC, and a PLSS built by Hamilton Standard. The EMU had similarities to the A7L, but differed in major respects:

Minor accessories included a drink bag; a cuff checklist; a wrist mirror to allow inspecting suit elements out of line of sight; and a set of D-rings to allow the suit to be hooked up to a work surface. When several astronauts performed simultaneous EVAs, the suits could be marked with colored rings around the thighs to allow them to be told apart.

The suit pressure was lower than the shuttle cabin pressure, partly to reduce ballooning; the SSA had restraint elements to control ballooning, but it was easier to do at lower pressure. The lower pressure meant the astronaut had to go through an extended period of "pre-breathing" to prevent from getting the "bends". Unlike earlier NASA spacesuits, the EMU suits weren't built specifically for an astronaut; they were modular, with some elements, like the arms, made in a set of sizes, with components "mixed & matched" for fit to a particular astronaut. The weight of the completely equipped suit ran to 115 kilograms (254 pounds).

NASA also developed a "Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU)" backpack system that allowed astronauts to perform EVAs without a tether for the first time. As mentioned, an Air Force-developed Astronaut Maneuvering Unit was flown on the Gemini 9 mission, but the AMU was never actually tested on an EVA. One interesting trick introduced in the shuttle program for EVAs was the use of a special foot pad that could be attached to the shuttle robot arm, allowing an astronaut to be moved around with the arm.

The EMU spacesuit was improved, resulting in the "Enhanced EMU (EEMU)" suit. The Enhanced EMU program didn't involve the introduction of a new model of suit, so much as it involved a series of ongoing and incremental updates that added up to a new model of suit, mostly with an eye toward ISS service. The first EEMU update, introduced in 1994, was a compact follow-on to the MMU "jetpack" in the form of an American version of the Russian SAFER pack for emergency rescue, strapped onto the bottom of the PLSS backpack, with arms running up its sides.

Other EEMU changes made over the next few years included:

NASA has been working on an "Exploration EMU (xEMU)" EVA suit for the Artemis and other programs -- but ILC didn't make the cut, NASA selecting a suit from Axiom Space in 2022. Details of the xEMU suit are unclear at this time.

BACK_TO_TOP* Given the elaborate evolution of pressure suits, IVA suits, and EVA suits, a summary is useful to keep them all straight. US suits include:

Soviet-Russian suits include:

* Companies working on commercial crewed space flight are also developing space suits. In 2017, Boeing publicly revealed a "Boeing Blue" IVA suit for the company's "Starliner" commercial crewed space capsule, developed in collaboration with DCC. It appeared to be at least inspired by the DCC G5C "grasshopper" suit developed for the Gemini program, with a zip-up "soft helmet". It was about 40% lighter than contemporary IVA suits, and had touchscreen-capable gloves. Although it did provide thermal protection, it was not uncomfortably hot to wear under normal room conditions, without external cooling. Zippers in the torso area permitted adjustment from sitting to standing position. Umbilical connections were on the front, so they were easy for the wearer to reach.

Not to be outdone, crews for the SpaceX Crew Dragon capsule also wear a new IVA suit, first unveiled in 2020. The Dragon "Starman" suit was actually based on a concept from Hollywood costume designer Jose Fernandez, who had designed costumes for movie superheroes. The suit engineers then worked from that as a style guide. SpaceX has been generous with promotional material on the suits, but not with technical details.

Although ILC didn't get the contract for the NASA xEMU suit, the company has developed a prototype of a soft EVA suit, the "Z-1", with a weight of about 73 kilograms (162 pounds). It featured a closed-loop PLSS that started out with a high pressure, then gradually cut back on the pressure in order to minimize pre-breathing. One particularly interesting feature on the Z-1 was the "suit port" plate on the back, which would mate up with a portal on a planetary rover or other habitat. With the suit port, the suit would be stowed externally, to be entered by the astronaut from the back, and the PLSS then attached via the portal.

The Z-1 prototype had green trim, giving it something of a resemblance to the "Buzz Lightyear" character of the Disney-Pixar TOY STORY movie series, and so it was called the "Buzz Lightyear suit". Disney, notoriously touchy about infringements on their copyrights, chose to let that one slide. ILC then built a follow-on, the "Z-2", with the suit port and the new PLSS, but with a HUT and less weight.

* There have been many spacesuits that never flew, and not all new spacesuits under development ever will, either. In fact, it is now an interesting question of whether EVA spacesuits even have a future. Refinement of "virtual reality" technology suggests the possibility of developing robots that could perform EVA tasks, under the control of astronauts working from inside a space vehicle or habitat. If a robot were up to the job, it would be much easier to have it do the work, instead of having to build a suit to provide the elaborate environmental support for an astronaut. Why duplicate the habitat in the suit if there is no reason to do so?

Taking this thought a big step further, if we were to send astronauts back to the Moon or to Mars, would they even need to land? Robots and other gear could be sent on one-way trips down to the surface, with the robots under the virtual control. Due to communications time lags, it would be difficult or impossible to perform virtual control from Earth, but there would be little or no perceptible time lag from orbit around the destination. A network of small communications satellites could be deployed from the orbital ship to maintain contact with the surface site.

It may seem perverse to send astronauts to another world and not have them actually land on it -- but if they have to wear spacesuits, they're still isolated from it, and a younger generation that's more comfortable with virtualization may not be too concerned about the distinction between that and exploring through a virtually-operated robot. If the objection is raised that it seems lacking in daring, taking a trip across space to another world would provide all the daring anyone would really want, such a mission having plenty of deadly hazards even without a planetary landing.

* Sources include:

Materials were also obtained from NASA and ESA videos, as well as their websites.

Illustrations details:

* This document was built up from notes for documents on the Apollo and Space Shuttle programs and released as an ebook in 2015. In 2022, I updated the ebook and made this document for my VECTORS website.

Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 oct 22 v1.0.1 / 01 jun 24 / Review, update, & polish.BACK_TO_TOP