* Work on pressure suits for aviators began before World War II, but it wasn't until after the war that the first practical suits were introduced. They were designed for military purposes, but were adapted to use in space when the first crewed space capsules were launched.

* In the years after World War I, as aviators began to reach higher and higher altitudes, life support became an increasingly difficult issue. Not only was there little oxygen at high altitudes to breathe, at low air pressures blood could boil, and the temperatures were very low.

One of the first people to consider development of a pressure suit for survival at very high altitudes was the Scots physiologist John Scott Haldane -- not to be confused with his son, the well-known biologist J.B.S. Haldane -- who suggested the idea in 1920 as a means of supporting high-altitude flight. Serious work in the concept didn't begin until the 1930s, driven by the high-profile extreme-altitude research balloon flights of the era, as well as the invention of the supercharger and later the turbocharger, which allowed piston-powered aircraft to reach much higher altitudes.

One of the first to actually work on the pressure suit was an American named Mark E. Ridge, who in the early 1930s tried to interest the US military in developing a pressure suit for an open-gondola balloon flight into the stratosphere. The military wasn't interested, so Ridge contacted John Haldane in London. Haldane had been working with Sir Robert Davis of Siebe, Gorman & Company on experimental deep sea diving suits; in response to Ridge's ideas, Haldane and Davis built a high-altitude protection suit, based on a diving suit, but with substantial modifications. The Ridge-Haldane-Davis suit was ground-tested in a vacuum chamber to a simulated altitude of 27,400 meters (90,000 feet); in 1936, a British Royal Air Force (RAF) pilot flew to 15,200 meters (50,000 feet) in a derivative of that suit.

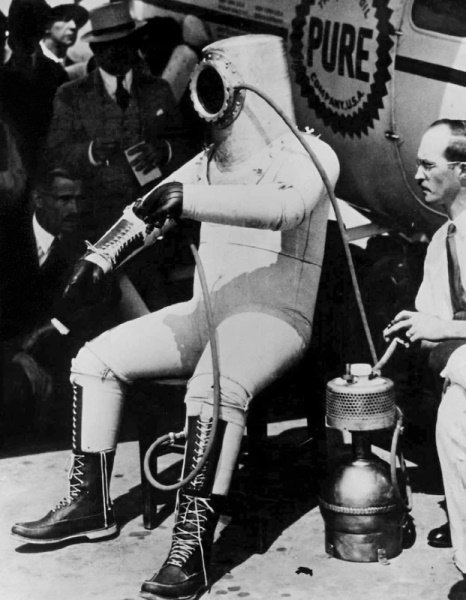

Well-known American aviator Wiley Post was also interested in pressure suits, Post believing that high-altitude winds could help him win long-distance flight records, if there were only some way to survive at such heights. Pressurizing the cockpit was problematic, both technically and because it would add too much weight -- and so in 1934, Post worked with the B.F. Goodrich Company, in collaboration with Goodrich engineer Russell Colley, to build a pressure suit.

Their first suit couldn't maintain pressure; the second suit proved too tight, with Post having to be literally cut out of it. Post and Colley largely redesigned the suit; the third iteration was workable, if only just, with Post finally wearing it on flights to high altitudes in 1934. Oxygen was provided by an external tank, with heating provided indirectly by the aircraft engine. That was as far as the matter went for the time being, Post being killed in an air crash in Alaska in 1935 that also killed humorist Will Rogers.

* From the mid-1930s, threats to peace began to emerge, leading to the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. Up to and through the conflict, most of the major combatants worked on pressure suits, though none saw serious operational service. The Italians developed a "semi-rigid" suit that permitted access through an aperture in the back; while it proved impractical, the ideas embodied in its design had merit, and would be revisited later. In the USA, work on a pressure suit design crystallized into "Project MX-117", initiated by the Army Air Corps in 1939, with a network of companies working on the effort, including Colley's group at B.F. Goodrich; Bell Aircraft; the Goodyear Rubber Company; the US Rubber Company; and the National Carbon Company.

* From 1940 through 1943, these research groups came up with a number of new pressure suit designs. As a rule, the MX-117 suits featured transparent dome-like plastic helmets and airtight rubberized fabric garments, which tended to suffer from "ballooning" -- the suit would ?spread-eagle? or "starfish" under inflation, making movement difficult. Wiley Post's final suit had featured a quilted cover garment to restrain ballooning; the suit was also built with the seated position as the default, and its helmet was strapped down to prevent it from "riding up" from his shoulders.

A major breakthrough came in the development of accordion-like semi-rigid joints -- fabric over alternating small-large rigid hoops -- at the knees, hips and elbows, which did much to improve mobility. Such suits were nicknamed "tomato worm suits", in honor of the segmentation of the tomato hornworm caterpillar's body. The suits designed under the MX-117 program provided considerable inspiration for sci-fi art and movies of the 1940s.

The US Army Air Forces (USAAF) -- which had superseded the Air Corps in 1941 -- pushed development of pressure suits to support high-altitude bombing; but interest in high-altitude flight operations faded, with enthusiasm for pressure suit fading as well. The USAAF Army canceled the MX-117 program in 1943, though studies continued on "anti-G / anti-gee" garments for fighter pilots, which used inflatable bladders that restricted blood flow to keep fighter pilots from blacking out under high-gee maneuvers.

The Soviet Union had also tinkered with high-altitude pressure suits in the early 1930s. At the time, there was an international competition in high-altitude balloon flights, something like an early "space race", which drove efforts to develop a protective suit for such purposes. Initial work was performed by engineer E.E. Chertovsky of the Aviation Medicine Department of the Civil Air Institute of Scientific Research in Leningrad (previously and now Saint Petersburg). His first suit, the "Ch-1" of 1931, was a nonstarter, suffering badly from ballooning. Chertovsky went on to develop the improved "Ch-2" through "Ch-7" suits, the last introduced in 1940, with better flexibility and other improvements.

In the meantime, from 1936, the Central Aerodynamics & Hydrodynamics Research Institute (TsAGI in its Russian acronym), the primary Soviet organization for aeronautical research, conducted work on pressure suits. The first TsAGI suit, the "SK-TsAGI-1", was introduced in 1937; it featured accordion-style joints for flexibility and a "closed-loop" air system, featuring a lithium hydroxide ?scrubber? to clean carbon dioxide out of the air for re-breathing ? respiration actually doesn't convert much oxygen into CO2 with each breath, but once CO2 concentrations reach about 1%, it becomes noticeably toxic, and can be lethal at higher concentrations.

TsAGI constructed a series of suits up to the "SK-TsAGI-8" of 1941 -- when work was halted by the Nazi invasion, and effectively given up for the duration of the conflict. The Red Air Force was operationally focused on front-line support, and had little interest in high-altitude operations.

BACK_TO_TOP* During World War II, Dr. James P. Henry of the University of Southern California experimented with a new concept in aircrew protection, leading to the first of what became known as "capstan type" partial pressure suits. Henry's partial pressure suit operated by exerting mechanical pressure on the body, compressing the abdomen and limbs in the manner of a gee-suit through the use of inflatable bladders in the abdominal area and pneumatic tubes (capstans) running along the limbs. The wearer's head was fully enclosed in a tight-fitting, rubber-lined fabric hood, fitted with a transparent visor and fed by oxygen delivered through a corrugated rubber hose.

Henry contacted the David Clark Company (DCC) to develop his suit concept. DCC had actually started out before the war manufacturing brassieres and other lingerie, but due to the diversion of rubber to military use during the war, had gone into the business of making anti-gee suits and other gear for the government. DCC was overwhelmed with military work and didn't have resources to spare at the time, but the company did remain in contact with Henry, and provided support to his lab for experiments.

Following the end of the war, the company was able to work with Henry to develop the "S-1" partial pressure suit, which led to a series of refined derivatives. Trying to nail down the evolution of military pressure suit series is confusing, frustrating, and not entirely relevant to a document on spacesuits; enough to say that one of the significant early derivatives was the "T-1". Only the helmet of the T-1 provided air pressurization, with a tight neck seal ensuring the air didn't leak out; the suit itself provided pressure simply by constriction.

The T-1 was of course very snug-fitting, and so was very uncomfortable for prolonged use. Later derivatives of the T-1, the "MC-3" and "MC-4", were not much of an improvement in terms of comfort, though helmet designs did advance considerably. These suits could be worn with a coverall garment to ensure the capstans didn't get snagged on cockpit controls; they became something of a trademark of pilots of experimental rocket planes and the like of the era.

* Work also continued in the USA on development of full pressure suits. The US Navy introduced an experimental suit, the "Mark I" in 1956, which led to an operational suit, the "Mark IV", in 1958. The Mark IV became the standard high altitude suit for US Navy aviators.

The military pressure suits of the era tended to be similar in configuration. They all featured a layered set of "garments":

The garments could be and often were combined -- for example, a pressure garment might have a liner layer, while the cover garment might incorporate restraints. It is not always easy to determine from documentation exactly how many separate garments each type had. Of course, a suit was completed with boots, gloves, helmet, and other accessories, often including a survival kit.

In the Mark IV, the cover garment was military green, made of nylon, and incorporated the restraint system -- which was based on non-stretching tapes, lacing cords, and zippers. The cover garment had a prominent zipper running diagonally down the front. A user wore regular military boots, but had pressurized gloves, which also with two layers and were connected to the suit via zippers. The helmet featured a tilt-up visor.

The US Air Force (USAF) -- the Army Air Forces became an independent service in 1947 -- took a different path. In 1955, the USAF issued a request for full pressure suit designs. The USAF needed such suits for high-altitude reconnaissance missions, and for the X-15 near-space rocket plane -- a collaborative program between the Air Force and the US National Advisory Council on Aeronautics (NACA, which in 1958 became the core of the new US National Aeronautics & Space Administration / NASA). A number of contracts were awarded, with two designs selected in 1957 as the most promising:

Incidentally, as with DCC, ILC got its start in the brassieres business, being well-known for its "Playtex" product line. The spacesuit business was originally handled out of a company division in Dover, Maryland, and so the company name is often given as "ILC Dover"; it is simply called "ILC" here for simplicity.

The Air Force chose the DCC suit for further development. The first David Clark full-pressure suit to go into USAF service was the "MC-2" suit, the developmental derivative of the XMC-2-DC suit. The MC-2 suit was used early in the X-15 program, with first flights in 1959. It differed significantly from the Mark IV in that the pressure garment was covered by a separate restraint garment made of nylon mesh -- the mesh being known as "linknet" and developed by DCC. The restraint garment was covered in turn by a cover garment.

The MC-2 left something to be desired and led to the standard Air Force high-altitude full pressure suit, the "A/P22S-2". It looked much like the MC-2 externally but featured many refinements, particularly an improved pressure garment and helmet -- the sealing scheme for the MC-2 helmet had left the helmet visor well forward of the pilot's face, resulting in "tunnel vision", and so the A/P22S-2 helmet placed the visor much closer, giving a better field of view.

From 1961, X-15 pilots wore a modified version of the A/P22S-2, with gee-suit features and an aluminized cover garment, as opposed to the plain cloth cover garment of the standard Air Force suit. The Air Force needed a solution faster than could be provided by the A/P22S-2, and so ironically the Navy Mark IV was adopted as an interim solution -- the USAF acquiring a modified version as the "A/P22S-3".

The Air Force MC-2 suit evolved not only into the A/P22S-2 suit, but also other refinements, including the "A/P22S-4", "A/P22S-6" (AKA "DCC S1024" in company nomenclature), and "A/P22S-6A" (AKA "DCC S1024B"). Pilots in the final flights of the X-15 program used the A/P22S-6, up to the end of the effort in 1968.

* Soviet work on pressure suits revived following World War II, with research being conducted from 1946 by the Gromov Flight Research Institute (Gromov LII in its Russian acronym), leading to the establishment of a formal research and development organization at State Factory 918 in 1952. The organization still is in the business of building pressure suits. It would be later renamed "Zvezda (Star)" -- exactly when it acquired the name isn't clear, but it is referred to as the "Zvezda" organization in the rest of this document for convenience.

Following up from the Gromov LII work, from 1953 to 1959 the Zvezda organization developed a series of high-altitude pressure suits, The initial series of suits, starting with the "VSS-04", all had a roughly similar configuration:

The "SI-1" series of suits from 1955 added such features as improved restraint and joint systems; gloves and boots that were easier to put on and take off; plus a spherical full helmet with a top-hinged faceplate. By 1959, the configuration had evolved to the "S-9" suit, which added an aluminized outer coverall garment and a solid helmet with an up-hinging visor; and then the "Vorkuta" suit, which had separate pressure and restraint garments.

Incidentally, in the early 1950s, Zvezda actually made pressure suits for dogs, as a component of high-altitude ejection tests. The dog suit was a pressure-tight bag, featuring stub extensions for a dog's front paws, made of three-ply rubberized fabric with a plastic bubble helmet. The suit was mounted in a frame on an ejection sled, with straps restraining the suit and its occupant to the sled, which carried the suit's oxygen supply.

BACK_TO_TOP* On 4 October 1957, the Soviet Union set off a competition in space by launching the first artificial Earth satellite, "Sputnik 1". It was followed by more Sputniks, and somewhat belatedly American satellites, leading to an effort to send a nonfunctional payload to the Moon.

Following in the tracks of the satellite launches, both the USSR and US set up programs to put a man into space. The Soviet program was named "Vostok (East)", in which a Soviet "cosmonaut" would be put into orbit using a derivative of the R-7 missile. Vostok was actually coupled to the Soviet space reconnaissance program, the Vostok being very similar to the "Zenit" imaging reconnaissance satellite, then being developed in parallel. Both Vostok and Zenit were built around a re-entry sphere or "sharik", which in the case of the Vostok carried the cosmonaut, and in the case of the Zenit carried cameras and film. The sharik would parachute down onto land; since the impact was still hard enough to kill the occupant, the cosmonaut would eject before the sharik touched down.

The Americans responded with the "Mercury" program, which envisioned sending an "astronaut" into space first on suborbital hops, using a Redstone battlefield rocket, and then into orbit on an Atlas missile. Mercury had no real connection to the US spy satellite program, that being pursued on a different track. Mercury would splash down into the ocean, the astronaut and capsule being recovered by a helicopter off an aircraft carrier.

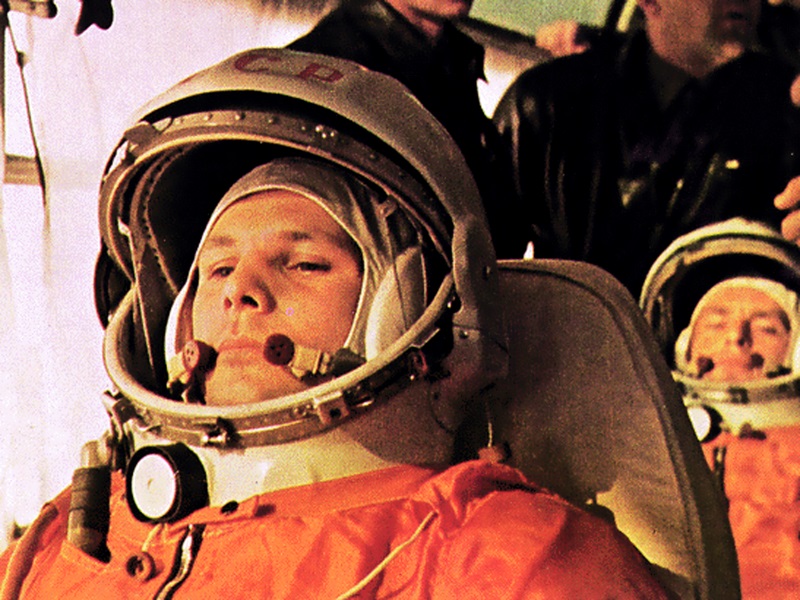

The Soviets won the crewed spaceflight race, putting cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin into orbit on 12 April 1961. The Americans responded within a month, sending astronaut Alan Shepherd on a suborbital hop on 5 May 1961. Over the next two years, there would be five more Vostok flights, as well as a second suborbital Mercury flight, and four orbital Mercury flights.

Of course, both cosmonauts and astronauts required spacesuits. Two different classes of spacesuits would eventually be developed by the USSR and the US:

The Vostok spacesuit was an IVA / rescue suit, being developed by Zvezda, which made the "S-10" prototype in 1959, leading to the operational "SK-1" suit ? "SK" standing for "Skafandr Kosmicheskiy (Diving Suit for Space)". The SK-1 was much along the lines of earlier Soviet military pressure suits, the major difference being that the cover garment was bright orange, to make the pilot more visible to recovery teams. Orange coloration would be a common, if not universal, feature of IVA / rescue suits. The helmet was solid, not removeable, and had dual visors.

The restraint scheme used a system of adjustable loop cords and steel ropes running from armpits to hips to control vertical ballooning, preventing the helmet from riding up on the cosmonaut's shoulders. A ratchet system was used to adjust rope length. The suit featured soft joints of the orange peel type. It had a total weight of 20 kilograms (44 pounds).

The SK-1 suit had an external life-support system, being supported by capsule systems, operating on an "open-loop" basis -- that is, without CO2 scrubbing. It did have a short-endurance reserve for high-altitude ejection; the cosmonaut also had a life vest and survival kit. The suit provided sanitary facilities to allow a cosmonaut to relieve himself. As with all the space suits used by both sides in the era, each suit was custom-fitted to a particular wearer.

The SK-1 suit was used on all the Vostok flights, with some improvements over time; a minor modification, the "SK-2", was produced for the flight of "Vostok 6" with cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space, the suit featuring minor modifications as appropriate to gender. Incidentally, Tereshkova was also the last woman to fly in space for almost twenty years: the Soviets weren't very enthusiastic about putting women in orbit, the Americans were even less so.

The Mercury spacesuit was a modification of the Goodrich's Mark IV high-altitude pressure suit for the US Navy, differences including:

The air supply was provided by an umbilical connection with the capsule. The "silver suit" appearance became a common item in sci-fi movies of the era. The Mercury suits were formally referred to by NASA as models "XN-1" through "XN-4", but they were generally referred to as "Quick Fix" suits.

The Mercury suit was tweaked during the course of the Mercury program:

Roughly in parallel with the Mercury program, the Air Force was also considering putting men in orbit, using the "X-20 Dyna-Soar", a spaceplane that was to be launched by a Titan III heavy booster. Of course, X-20 crew would require spacesuits, and so the USAF awarded a contract to DCC for an IVA suit, with DCC providing an evolved version of the A/P22S series. The Air Force also investigated EVA suit designs -- but nobody could really figure out what serious purpose the Dyna-Soar would serve, and so it was canceled in 1963. However, as discussed below, the Air Force was not quite out of the crewed spaceflight business.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Soviet Vostok flights were followed by two "Voskhod" flights in 1964:1965, while the US Mercury flights were followed by nine crewed "Gemini" flights in 1965:1966. The first Voskhod flight involved flying three cosmonauts in what amounted to a modified Vostok capsule. The "Voskhod 1" mission, performed in October 1964, was effectively a stunt, conditions being too cramped to permit the cosmonauts to do anything but endure. Space being at a premium, that meant that the cosmonauts couldn't wear IVA suits, a practice that would come back to haunt the Soviets.

The second and last Voskhod flight was "Voskhod 2", in March 1965. There were two cosmonauts, Alexey Leonov and Pavel Belyaev, instead of three on the flight, but it involved the very first EVA to be performed. That demanded development of an appropriate EVA suit, and work on the "Berkut (Golden Eagle)" spacesuit was initiated in the spring of 1964 on a crash program basis.

The Berkut was a modified SK-1 suit, with a self-contained backpack life support system (LSS) capable of keeping a cosmonaut alive for 45 minutes -- along with a backup umbilical to the spacecraft -- plus a removeable helmet, twin pressure garments, and a coverall garment with multiple thermal layers. Unlike the orange SK-1 coverall, the Berkut coverall was white to reflect sunlight.

Wearing the Berkut suit, Leonov performed the first EVA ever on 18 March 1965. Belyaev also wore a Berkut suit, in case he had to assist Leonov. Leonov had a good deal of trouble, the suit proving hard to move around in, and Leonov was even forced to partially depressurize his suit so he could get back into the space capsule -- but Soviet media still played up the event as a triumph.

Following Voskhod, the Soviets moved on to the "Soyuz" modular capsule, which could carry up to three cosmonauts. It didn't get off to a good start, with the "Soyuz 1" flight of April 1965 resulting in disaster, killing cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov when the landing parachutes didn't deploy correctly. Further Soyuz flights would generally go better, and indeed the Soyuz is still flying in the 21st century.

At the outset of the Soyuz program, cosmonauts still did not wear IVA suits, but EVAs were planned for the program, and so from mid-1965, Zvezda worked on a new EVA suit, the "Yastreb (Hawk)". The Yastreb suit was a follow-on to the Berkut suit, but the Yastreb added refinements, such an improved restraint system, the Berkut having suffered too much from ballooning; and a life support system that could maintain a cosmonaut for two hours. The LSS was closed-loop, with CO2 gas scrubbing, an open-loop system turning out to be excessively bulky.

Since the Yastreb was for temporary use in orbit, it had to be easier to put on and get off than the Berkut suit, and it also had a more effective joint restraint system using lines and pulleys. The Yastreb suit's LSS pack was worn on the front; one of the unusual features of the Yastreb was that the pack could be slipped down over the legs to make getting in and out of a hatch easier. The Yastreb suit was only flown on Soyuz 4 / Soyuz 5 -- a dual mission performed in January 1969 that involved a docking between the two spacecraft and a crew transfer.

The US Mercury capsule had been little more than a technology demonstration, to show that a human could be put into space, survive there for a relatively brief period, and then be brought home safely. The US had committed to landing on the Moon under the "Apollo" program; Gemini was a two-man capsule intended to evaluate technologies and procedures for a Moon voyage, including flights with a duration of up to two weeks, and rendezvous between two spacecraft.

The nine crewed Gemini flights were "Gemini 3" through "Gemini 12". On the initial Gemini flights, the astronauts wore David Clark Company "G3C" spacesuits -- the designation meaning "Gemini Type 3 suit, Clark company" -- with an evolutionary relationship to the A/P22S suits David Clark built for the X-15 program. The most significant difference was that the cover garment was more sophisticated, being made of nomex synthetic -- a polymer similar to nylon but fire-resistant, sometimes called "high-temperature nylon" AKA "HT-1". The cover was white instead of aluminum; some training suits had the aluminization and were worn by astronauts in publicity shots early in the program. As with the Mercury suit, the G3C was supplied with oxygen from spacecraft systems.

The Gemini 4 flight, the crew being James McDivitt and Edward H. White, involved the first American EVA or "spacewalk", which had been hastily inserted into the flight plan in response to Leonov's EVA, the issue of EVA not being seen as a particularly big deal at NASA. The astronauts wore improved David Clark "G4C" suits, the primary change from the G3C being addition of a "thermal / bumper" garment, between the restraint garment and the nomex cover garment. The thermal / bumper garment consisted of a layer of felt to provide micrometeorite protection, over layers of alternating mylar polymer and dacron cloth to provide thermal protection. The dacron interlayers provided an "airspace" that retained heat, sealed in by the top and bottom mylar layers.

The G4C suit came in two configurations: what amounted to an IVA suit for an astronaut who remained in the capsule, and an EVA suit for the astronaut performing a spacewalk. Astronaut Ed White's G4C suit for EVA differed from the IVA suit configuration by featuring a thicker thermal / bumper garment, plus overgloves for thermal protection, surfaces could get very hot or cold in space, and a second visor with a gold film to block solar ultraviolet (UV) -- there being no atmosphere to block ultraviolet, it would be very easy to get a brutal sunburn.

The EVA G4C was supported by a 7.6-meter (25-foot) umbilical to the spacecraft, backed up by a reserve oxygen supply good for a few minutes, in case something went wrong with the umbilical. White found his spacewalk a marvelous experience -- though as it turned out, only because he wasn't trying to get any work done. The Gemini 7 flight was a long-duration test, carrying astronauts Frank Borman and Jim Lovell on a 14-day mission. Since they were not going to perform a spacewalk, they were outfitted in new David Clark G5C lightweight spacesuits that only weighed 7.3 kilograms (16 pounds). They were comfortable and easy to take off and put on; the crew wore pilot-style helmets under soft hoods. The suits had large faceplates that gave them an insectlike appearance, and so they were called "grasshopper suits". They were only used on Gemini 7, the remaining Gemini missions using G4C suits.

A spacewalk wasn't performed again until the Gemini 9 flight, with Tom Stafford and Eugene Cernan. Cernan was to make the second US EVA, scheduled to last almost three hours. Cernan was supposed to remove an "astronaut maneuvering unit (AMU)", a big pack fitted with a thruster system developed by the Air Force, from the Gemini's adapter section, and test it out. He was wearing a specially modified David Clark G4C EVA suit that had heat shielding over its lower backside, using a mesh known as "Chromel-R" -- an alloy, mostly nickel, with 10% chromium -- to protect it from the AMU's thrusters. Cernan also had an enhanced life-support pack, mostly to support a cooling system; life support was still provided by an umbilical from the capsule.

The Soviets had said nothing about Leonov's desperate effort to get back in the Voskhod, and Ed White's short stint of floating around in space had looked like a joyride. Cernan had trouble from the start, wrestling with his umbilical, turning and tumbling, struggling with a spacesuit that strongly resisted his every move. Although he had spent a considerable amount of time in the gym before the flight to condition himself, he still became overheated and exhausted. In the end, Cernan had to cut the EVA short after two hours, and had considerable trouble getting back into the Gemini capsule. The AMU pack was not used, and would not be flown again. It was obvious that NASA needed to rethink how EVAs were performed.

EVAs were conducted on the last three Gemini flights, though it wasn't until the final mission, Gemini 12, with the crew being James Lovell and Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin into orbit, that NASA was able to conduct a really satisfactory EVA, though improved training, plus fit of handrails, footholds, and tether connection points on the spacecraft. EVA had been a troublesome experience for NASA, but Gemini had proved its worth in making sure they weren't so much trouble in the future. The experience also led to refinements in the next generation of EVA suits, as discussed below.

Although the Air Force Dyna-Soar program was, as mentioned above, given the axe in 1963, the USAF was interested in the Gemini, planning on using it as an element of the "Manned Orbital Laboratory (MOL)", which was a two-crew space station, to be launched on a Titan III booster, with a Gemini on top for the crew's return to Earth. MOL required spacesuits of course, and so the Air Force obtained a set of IEVA suits from ILC, DCC, Litton, and Hamilton Standard. A dummy MOL was flown in 1966, but the program was killed in 1969, and none of the MOL suits ever flew. They did, however, provide contributions to spacesuit technology in general.

BACK_TO_TOP