* The workings of the mind are readily observed through well-established tools, most importantly "heterophenomenology" -- that is, the use of reports of test subjects as data. Experimental probes of cognition, and consciousness, are now highly refined and effective. Mainstream behavioral psychology of course has insights into the mind as well, as does a more generalized approach, known as "intentionality".

* Dualists often say the human mind is beyond our ability to inspect and to understand. Nonsense. We know what the mind is, it's the brain in runtime, the brain's virtual machine, and we can study behaviors -- its cognitions -- including perception; planning and problem-solving; memory; learning; language; and imagination. We can observe all such cognitions in carefully-designed experiments with test subjects, observing their behavior in response to a test, and recording their reports on the experience. If desired, we can monitor their brain neural activity monitored to find a relationship between a particular neural activity and a particular experience.

There was a time when any such introspective reports were regarded with suspicion in cognitive science, and not without cause. The sciences are based on objective reliable observations, not subjective impressions -- that is, science takes a "third-person" point of view (POV), while reports are from a "first-person" POV.

The objection to using personal reports on what goes on in people's minds is that it is absurd to use first-person reports on events of the mind as third-person evidence. However, that's all we've got. Yes, we have means of observing the functioning of the mind, but the only thing available for describing the experience associated with such activity are reports of the test subjects.

There is no reason to dismiss personal reports out of hand as unreliable and irrelevant. Opinion pollsters obtain reports of personal opinions in quantity all the time. Although opinion polls are often badly done, the methodology for conducting good polls is well established:

It is easy to spot dishonest "push polls" which are often conducted by advocacy groups; they ask biased and leading questions, the goal being propaganda instead of information-gathering. Professional polling organizations tend to conduct much more robust polls.

To be sure, it is completely obvious that the only information a poll can obtain is: "What do you think?" -- but that is precisely the question being asked in cognition-consciousness studies. More generally criminal trials, on which much may hang, use eyewitness reports as a normal procedure. Criteria for judging the validity of witness reports have been established, with the credibility of such reports increasing with:

There's also the important question of the pertinence of witness reports. If questions are asked of witnesses about cognitive processes, it is important to sort out specifics from conjectures. We can ask witnesses what they saw, or felt, or remembered, or thought to do under certain situations -- and if they give a coherent story that holds up under cross-examination, then in the absence of a credible alternative story, the responses can be taken seriously.

Certainly, if Alice asks Bob to hold out his hand flat and tells him to close his eyes, then gently prods one of his fingers with a pin, Bob will report which finger it was, and if he felt any pain. We have no cause to question his report. If we tracked the activation of the neural pathway associated with the prod, we would then have a correlation between that pathway and the sensation felt by Bob.

The conjectures of witnesses, in contrast, are of limited value. It is, for example, common for people to believe they have an immortal soul -- but since they can never provide a single unambiguous detail of it, the only thing we can learn from such reports is that people have an ingrained inclination to believe in the immortal soul. Of course, as Stanislas Dehaene pointed out, such common assertions are intriguing to science, since they pose the question: Why do we believe such things, when we have no honest reason to do so?

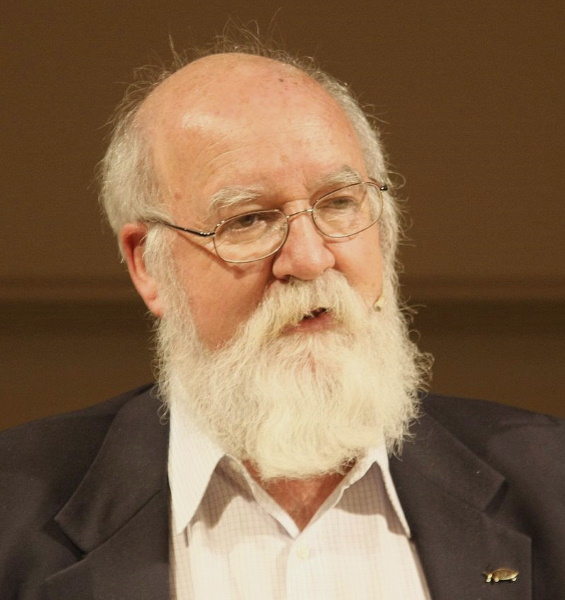

In any case, the philosopher / cognitive researcher Daniel Dennett (1942: 2024) liked to call the derivation of objective data from first-person reports "heterophenomenology" -- and apologized for using such an ugly-sounding word.

It's not really so ugly in practice, Dennett commenting in a 2003 essay:

QUOTE:

Heterophenomenology is nothing new; it is nothing other than the method that has been used by psychophysicists, cognitive psychologists, clinical neuropsychologists, and just about everybody who has ever purported to study human consciousness in a serious, scientific way.

END_QUOTE

All Dennett was saying was that there is no difficulty in observing the turning of the wheels of the mind -- we've been doing it for a long time. We can observe the behavior of test subjects, ask them questions, and perform controlled experiments on them. People check each other out on a casual level every day, to obtain understanding.

BACK_TO_TOP* Very well, there's no real problem in observing the cognitions of the mind; but what about consciousness, over which so much fuss is made? Dualists are inclined to claim that consciousness is completely beyond understanding. Yes, there was a time not too many decades past in which the scientific community avoided the term consciousness, the general opinion being that it was undefineable.

Not at all. Consciousness is one of the two aspects of the brain's behaviors: everybody knows there are things going on in the mind of which we are conscious, while there are other things of which we are not conscious. Dehaene suggested consciousness involves three elements:

Of course, if it just recognized a particular object and automatically took a predetermined action -- seeing a fire and setting off an alarm, for example -- it would be operating reflexively, not really thinking things over. However, that's still a big step towards consciousness. Once we get to the point of thinking over what to do next, assembling a solution from the elements of a world model, we're obviously mindful. Of course, we can remember the solution and, more or less as a reflex, use it again when the same circumstances arise.

To be sure, consciousness is, as Dennett noted, an ensemble of capabilities, with vigilance, attention, and conscious access providing elements. Some organisms have a much more limited capabilities than others. Nonetheless, if we're up and about, and doing something that requires mindfulness, nobody sensibly disputes that we're conscious.

Some claim introspection -- self-examination -- as an issue in consciousness, and certainly we do a lot of "thinking about thinking" AKA "metacognition". However, metacognition is only part of our thinking. Alice, when engrossed in an activity, focuses on the activity, and in a Zen fashion takes action with little self-consciousness. Self-examination isn't a continuous element of consciousness, our own selves only being a component of all the many things in the world that we spend our time considering. Some people are by habit far less self-conscious than others.

True, sometimes Alice is self-conscious. Again, if we perceive, we will also perceive ourselves perceiving. If Alice thinks something unexpected to her, she may ask herself: "That's odd, why did I think that?" -- and examine her memory of it. Similarly, if she makes a mistake, she may reflect on what went wrong to figure out a better way of doing things. Such introspection may seem confusing, another strange loop that leads to an infinite recursion, but that's over-thinking matters. Video presentations of sports events do "instant replays" all the time; nobody sees that as conceptually troublesome, and there is no infinite recursion involved. We could re-enter a memory loop as many times as we wanted, though it would be obsessive to do it persistently.

Metacognition does imply there are different elements in the mind often working at different purposes, any unusual thought or perception often provoking the self-skeptical question of: "Did I get that right?" Of course, there are people who never have any skepticism about their actions; they are best avoided.

BACK_TO_TOP* In sum, consciousness is an aspect of the behaviors of the mind, and is just as open to inspection as the behaviors themselves; they are inextricably linked. Dehaene spent much of his career conducting experiments to probe cognitive processes, in particular to pin down the borders between the conscious and unconscious, using optical -- or auditory, or tactile -- illusions and other fundamental experiments to see what people are aware of; what they are not aware of; and what registers on them, even when they're not aware of it.

Cognitive experiments actually go back almost two centuries. One of the first recognizably modern cognitive experiments was conducted by the English scientist Sir Charles Wheatstone (1802:1875) in 1838. He had invented the "stereoscope" -- the ancestor of the later "ViewMaster", a viewing device in which a subject views, with each eye, the same scene, but imaged from a slightly different angle. The same principle is embodied in modern "virtual reality (VR)" googles. With all such devices, the brain processes the two images to give an illusion of depth.

Wheatstone got curious as to what would happen if a subject were asked to view two different images instead, making sure that all a subject could see was the two images, and not be distracted by backgrounds. The result was that the subject shifted back and forth in attention to the two images, not being able to focus on both at the same time; the subject could try to maintain focus on one for a time, but with little success.

The phenomenon became known as "binocular rivalry". By extension, as "attentional rivalry", it applies to any sort of rivalry between senses, for example vision and hearing; we can't be reading something and attentively listening to something at the same time. This was pointed out as long ago as Descartes, and the insight likely wasn't original to him.

Subsequent cognitive experiments to the present day may not need any elaborate apparatus; though in the 21st century, they may be reliant on computers, and can make use of EEG and fMRI to monitor brain activity. One significant simple test was performed by psychologists Lloyd and Margaret Peterson in the 1950s, on short-term memory. Participants were shown three-letter strings, like "QVA" or "PNR", and then asked to recall them. After 3 seconds, they could recall 80% of them -- but after 18 seconds, they could only remember 10%.

Cognitive experiments on unfortunate people with localized brain defects have been particularly interesting. Significant work has been done on subjects with "blindsight", in which people who are blind due to a brain injury, not due to any defect of the eyes, can still recognize and respond to patterns in tests. Blindsighted people can, in some cases, navigate down a hallway featuring obstructions without difficulty.

Dehaene's work demonstrated that even normally-sighted people have a degree of blindsight. If a sequence of characters is displayed in rapid succession, the viewer will usually see the first one, but not a later character displayed for a very short interval. However, monitoring of the brain shows the hidden character will still be seen, but not made conscious.

Other intriguing experiments have been conducted with patients suffering from "split-brain syndrome", the ground-breaking research in the field having been performed by psychologists Roger W. Sperry (1913:1994) and Michael Gazzaniga (born 1939); Sperry shared the 1981 Nobel Prize in Physiology & Medicine for research on the subject.

In rare cases, patients with severe epilepsy have obtained some relief from the affliction through a surgical operation that involves cutting through the corpus callosum, the bridge between the two brain hemispheres. For the most part, split-brain patients (SBP) act normally -- but tests can be performed that show each brain hemisphere is, to a degree, "doing its own thing".

For example, suppose we have an SBP named Steve. If different songs are played to Steve simultaneously, using an earbud headphone in each ear, then if he's asked to sing what was heard, he'll sing the melody of the song that he heard in his left ear, with the lyrics of the song he heard in his right ear. This is due to the specializations in the brain hemispheres. The left brain hemisphere has control over speech -- note that the left brain hemisphere is hooked up to the right side of the body, while the right brain hemisphere is hooked up to the left side of the body. As a result, the left brain hemisphere focuses on the lyrics instead of the melody, while the right brain hemisphere doesn't pay attention to the lyrics, instead focusing on the melody.

There was some notion early on that SBPs had two personalities in one head, but that has been judged an exaggeration: yes, there are two parallel streams of consciousness, but they are indirectly linked in various ways. They remain too mixed up with each other to completely go their separate ways. SBPs generally get along well enough, because the two hemispheres have to react to the same environment and same events, and also acquire means of coordinating the actions of the two hemispheres.

For example, if Steve reaches for something with his right hand, under the control of the left hemisphere, the right hemisphere will generally play along and help with the left hand. It is an interesting question as to whether Steve could play the piano; he might find it clumsy to learn to do so, but it would seem to be just a question of one hemisphere listening to what the other hemisphere is playing, and then playing along. It would be like two people playing a piano duet, each playing with only one hand.

Occasionally, however, there can be confusions or disagreements, with the two hands doing unrelated or contrary things. Presumably, over time, each brain hemisphere becomes more experienced and sensitized to what the other brain hemisphere is doing, and gets better at second-guessing it. The interaction of the two brain hemispheres is unavoidable and continuous; they have no alternative but to get along.

Cognitive experiments have also been conducted to show how selective our awareness is. Two American cognitive researchers, Christopher Chabris (born 1966) and Daniel Simons (born 1969), created a 25-second video that they would show to groups of subjects. The video involved a half-dozen people in white shirts passing a basketball around in an elaborate fashion, asking them beforehand to concentrate and count how many times the ball changed hands among half the group. Afterwards, the group was asked if they noticed the man in the black gorilla suit -- who, during nine seconds of the video, walked into center stage, pounded his chest and roared, then walked off again. Whenever this experiment was performed, the majority of the group did not notice nor remember the man in the gorilla suit.

The researchers came up with a variation on the same video, in which watchers knew the gorilla would make a showing, but changed background details during the video, with everyone cued to notice the gorilla, but few noticing anything strange going on. Similarly, the London Transport Board made a short video named WHODUNIT, that involved a detective doing the "Miss Marple" thing, to pick the culprit out of a group of suspects. It's not revealed until after the culprit is arrested that a gang of stagehands was energetically running around the edges of the scene during the shoot, changing detail after detail, invisibly to the viewer -- the moral of the video being: LOOK OUT FOR CYCLISTS.

Of course, subtle -- sometimes not so subtle -- discrepancies from scene to scene are nothing unusual in video productions. The production staff will include a "gaffer", to make sure a scene is consistent in details from shoot to shoot. There are people who have a hobby of spotting and documenting such "gaffes" in videos that weren't caught, but most people don't notice them unless they are glaringly obvious.

Dan Dennett once participated in an experiment in which he was inspecting text on a computer display, with an eye-tracking system observing where his eyes were focused on the text. In the course of the experiment, the software controlling the text display would make changes in the text, exchanging one word for another one of similar length. Anyone standing behind him watching the text display could easily see the text flickering; Dennett saw nothing amiss.

The same experiment has been more recently done using images, with faces swapped, for example; subjects rarely notice anything wrong. This failure to spot visual discrepancies is known as "change blindness". It isn't news to stage magicians and makers of optical illusions, who have long known it is not so hard to trick an audience.

BACK_TO_TOP* Cognitive psychology is one of two main branches of psychology, the other being "behavioral" psychology. Cognitive psychology inspects the workings of the brain as manifested in and correlated to behavior; behavioral psychology simply observes how people think, without much concern for the operation of the brain. The two are sometimes seen as at odds -- but they're more complementary, each informing the other. After all, if somebody wants to understand the Alien Attack game, they can just observe its behaviors of the game without having any more than the most general idea of the smartphone hardware. Of course, we do get a fuller understanding of the game if we know how the hardware executes it.

As an example of the leverage behavioral psychology gives in understanding the mind, in 1999 psychologists David Dunning (born 1960) and Justin Kruger (born 1973) of Cornell University published a study in which they compared the competence of students to the self-assessments of those students to their own competence. It turned out the least competent students considerably over-estimated their competence, while the most competent tended to under-estimate theirs. This has become known as the "Dunning-Kruger (DK) effect" -- or sometimes "Climbing Mount Stupid" or, somewhat less harshly, "Climbing Mount Clueless".

Given a chart graphing confidence against actual knowledge, the "0" point for knowledge gives confidence of "1"; that's Mount Clueless. As knowledge increases, the confidence quickly drops off to a low level, to slowly rise with accumulated expertise, but not reaching "1" again. The DK effect demonstrates there is no clear dividing line between cognitive and behavioral psychology, since the effect reflects on a necessary element of cognition -- the relationship between knowledge and perception of knowledge:

If we think towards a particular end, as opposed to idle speculation or daydreaming, we need to know that we're on the right track, or at least could be on it. Any cognitive process that works toward a goal requires:

It is fairly easy to determine progress in, say, putting together a jigsaw puzzle, as we put together the pieces; and completion, when we put the last piece in. For less cut-and-dried cognitive tasks, it may not be so easy to recognize progress or success.

Hume pointed out that belief is emotional -- belief being a conviction, a feeling, that something is true. That feeling may not be solidly grounded in reality. Sensible folk may head off on a course of action that they believe might pay, but aren't confident that it will. As per the DK effect, people who know nothing about a task, but still charge forward confidently, are too ignorant to realize they're just spinning their wheels, never admitting they don't know what they are trying to accomplish. Again, such people are best avoided.

The DK effect does reinforce the conclusion that subjective reports can be regarded as reliable -- in that it says we can, with a high degree of reliability, expect incompetent people to overstate their competence. We may confidently dismiss uncorroborated testimony of people not known for competence, since they are known to be unreliable sources of information.

* Psychology concerns itself with what people are thinking. In probing the mind, that may be more than is necessary. It may be more useful to take a pragmatic approach, observing people's behavior to determine their intent. If Bob goes into the kitchen and gets food, Alice knows that he's hungry and is going to eat, no question about it; Bob's exact mental processes aren't so clear, but there's not much ambiguity about his intent.

Similarly, when Alice is at work, she concerns herself less with why her colleagues behave the way they do, than with what they are doing. Some she knows, from their behavior, that they are generally friendly and reliable; others friendly and not so reliable; some indifferent and distant; others hostile, and to be avoided. When she's driving, she has to similarly determine the intent of other drivers: is a driver going to let her get into the traffic flow on the freeway or not? Much hangs on the answer.

We can similarly determine the intent of animals. Suppose we see Ella stalking carefully through the back yard; we can easily see that she's stalking a bird, or possibly some other small mammal, or less possibly sneaking up on another cat -- the last being clearly playful in intent. However, intent doesn't stop there; we also recognize that Ella is a predator, and is adapted to hunting small prey, even without considering what she's actually doing at any one time. Scaling up to a tiger, we know better than to walk into a tiger cage at a zoo, because we know that a tiger is a predator big enough to kill a human, and is very likely to do so given the opportunity.

Extending the idea further, even a virus has an intent; it is genetically programmed to infect our cells and replicate. There's no reason to limit intent to organisms, either; a heat-seeking missile clearly intends to shoot down an aircraft, in fact it doesn't have any other intent. It has that intent built into its design, remaining apparent even when the missile is stockpiled. Indeed, there is an intent built into a can-opener: to open cans. Of course, there's no intent in, say, a rock or a planet; they can be put to various uses, but there's no good cause to think they exist to do anything in particular. They just exist.

We have now generalized thinking about intent to the notion of "intentionality", a term that often comes up in cognitive studies. It's a complement to psychology: instead of trying to get into people's heads to know why they are doing something, we just watch what them to see what they're trying to do, and don't care so much to figure out why. It may be so obvious as to not need further inquiry.

* In any case, there are things cognitive experiments and the reports obtained from them can tell us, things they cannot, and the study of cognition inevitably ends up being channeled by those constraints. Not at all incidentally, with this approach cognition / consciousness are necessarily defined in behavioral terms. There's nothing else there to discuss -- they're not things in themselves, they're behaviors. Dualists keep looking for something else there, some sort of Harvey, but they can never say anything of substance about it, because there's no substance there.

BACK_TO_TOP