* Charles Darwin's research led him to the construction of a theory of evolution of life on Earth. He realized from the start of the exercise that his theory would be controversial, and spent two decades amassing evidence to make sure he could make a credible case. He was finally forced to go public when he learned, by sheer chance, that a younger naturalist named Alfred Russel Wallace had come up with the same idea. The publication of Darwin's THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES in 1859 was one of the landmark events of the 19th century. The book proved just as controversial as he had expected, though it also proved influential, helping Darwin to acquire allies -- foremost among them the dogged Thomas H. Huxley.

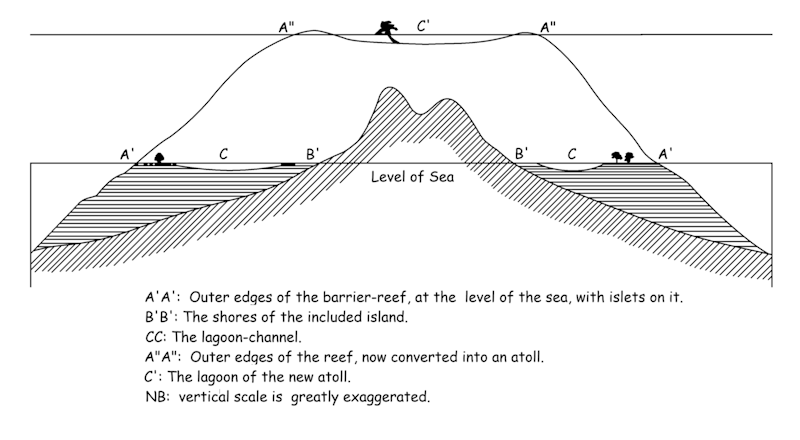

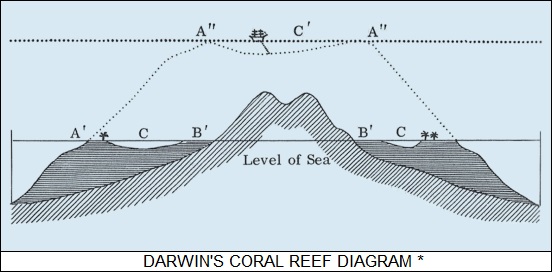

* In 1842, the year he set up house in Down, Darwin published THE STRUCTURE & DISTRIBUTION OF CORAL REEFS. It helped enhance his scientific reputation and would earn him honorable mention in the history of geology. Earlier scholars had believed atolls, the little islands consisting of a ring of coral concretions, grew on top of the rim of extinct, submerged volcanoes. Darwin, absorbing Lyell's gradualism, saw a progression in time from the "fringing reefs" that hugged the shores of an island, to the "barrier reefs" that set up a remote wall around an island, to the atolls. A fringing reef would grow up around an island; as the island subsided or eroded away, the reef would continue to grow, forming a barrier reef; and once the original island disappeared, all that would be left was the atoll.

However, Darwin's legacy would prove to be more than just a footnote in geology texts. The enormous pile of observations he had acquired during the voyage of the BEAGLE were in the process of being assembled into a theory of the origins of species. Beginning in 1837, Darwin had begun writing up a set of notebooks, with the pattern of his ideas coming together in a fit of note-writing. The fact that different families of species were found in different geographic locations suggested that each family was derived from a common ancestor, which had arrived in that locale in the past, with the "family resemblance" of members of the family, such as the birds of the Galapagos, also suggesting derivation from some common ancestry. Darwin knew from the variation in domestic animals, such as dogs or pigeons, that species were mutable, capable of being changed greatly in form. Lyell's gradualism gave a timescale on which such changes in species might take place, but that left one big problem: what mechanism focused the changes?

The answer had come to him in 1838, after reading the ESSAY ON THE PRINCIPLE OF POPULATION, published in 1798 by the pioneering economist Thomas Malthus (1766:1834). Malthus suggested that human populations tend to increase faster than their food supply, with the limit on the food supply finally putting a cap on the numbers of individuals. Darwin now saw matters clearly: species competed to eat, to reproduce, to avoid predators, to endure disease and harsh climate, and those more successful in the game would dominate while the less successful would die out. If any chance variations occurred in specific individuals that made them more successful in this "struggle for existence", those changes would be passed on, with changes gradually accumulating to the extent of creating new species. Darwin called the concept "natural selection", as a foil to the "artificial selection" used to create new domestic varieties of plants and animals.

In 1842, the year he published CORAL REEFS, he wrote out a short sketch of his ideas. In Darwin's view, there was no fixity of species. Instead of a particular species being created according to a fixed template, in modern terms like a specific model of car or other vehicle, a particular species was an interbreeding population of similar organisms, with a range of variation around a set of average or, in the statistical sense, mean characteristics. Over time, pressures on that population, due to competitors, predators, changes in climate, and so on, would shift the mean of that population, or in other words created a changed species. If a particular species was split into two populations -- by some geological change that created a barrier, migration of some members of that population, or some variation in habits that isolated a subgroup of individuals from the rest -- then in time the mean features of those two populations would vary enough to make them distinct, ultimately resulting in different species. That was exactly what he saw with the finches of the Galapagos.

Like Lyell's ever-changing Earth, species themselves shifted in a very gradual fashion over time, deep time, with those less fit to deal with the struggle for existence dying out, while those more fit to survive propagated and expanded their population -- indeed, a changing Earth necessarily implied changing species, adapting to altered environmental circumstances. The branching tree of species described by Linnaeus was not just an accident: it reflected the branching of species into other species over time through the probabilistic game of natural selection, with the "transmutation" of species taking place randomly as though through throws of the dice, and the results then being subjected to the tests of survival and propagation.

There was, in his view, no Higher Power as the Reverend Paley had envisioned as specifically guiding the creation of different species -- except for the Grim Reaper, who consigned the unfit to oblivion. Darwin understood the public would find this idea shocking. As far as he went, he didn't have a problem with that implication, having become more agnostic as he grew older. His naturalistic studies had made him very familiar with the cold cruelty of the natural world, the predation and the ghastly parasitism, a notion that he found difficult to reconcile with the idea of a benevolent Creator. The death in 1851 of his ten-year-old daughter Annie, apparently from tuberculosis, did nothing to encourage any different view.

Darwin never became an outspoken atheist, however; he simply didn't have that kind of confrontational personality, saying in his autobiography: "I have never been an Atheist in the sense of denying the existence of God". There was also the important fact that his wife Emma's religious faith was strong and unwavering. He could not criticize her faith -- though she was aware of his attitudes, and would try to tell him there was a bigger view of things that he might be missing in his focus on detail.

* The Reverend Paley might have said as much, and it would have been just as irrelevant to the facts of the natural world. Darwin was interested in such facts, down to an extraordinary focus on detail. Partly that was just his personality, but he also knew perfectly well that his ideas were going to run into resistance. The casual evolutionary speculations of his grandfather Erasmus simply wouldn't do; Darwin reread through ZOONOMIA, which he had once read with pleasure, in light of his new ideas and "was much disappointed; the proportion of speculation being so large to the facts given." Darwin knew he was going to have to make a very good case, since at the outset "the evidence in favor of transmutation was wholly insufficient; and ... that no suggestion respecting the causes of the transmutation ... was in any way adequate to explain the phenomena."

He was determined that no stone available to him would be left unturned in bolstering his theory, and that he would not go public with his ideas until he had nailed them down thoroughly. The world did not need another bout of foolish hand-waving about evolutionary ideas. By 1844, he had accumulated enough background to construct a full preliminary document on natural selection a few hundred pages long. However, that same year, a book titled VESTIGES OF THE NATURAL HISTORY OF CREATION, written under a pseudonym by a Scots journalist named Robert Chambers and proposing evolutionary ideas, became a best-seller. It was a colorful book, full of wild and sensationalistic notions, not the sort of thing that a reputable scholar would take seriously, and the British scientific community regarded it as dubious at best.

England was in a period of general social unrest and Darwin, always cautious, became even more so, and determined to make his case as solid as possible. He did make sure that a copy of his notes was set aside, to be released to the public if he died suddenly; his health was not good, being often afflicted with fits of the shakes, nausea, and vomiting. What afflicted him still remains a mystery. It may have been the infection he had picked up in Chile, but others suggest the whole thing was due to emotional stress. His ailment now seems beyond useful diagnosis in any case.

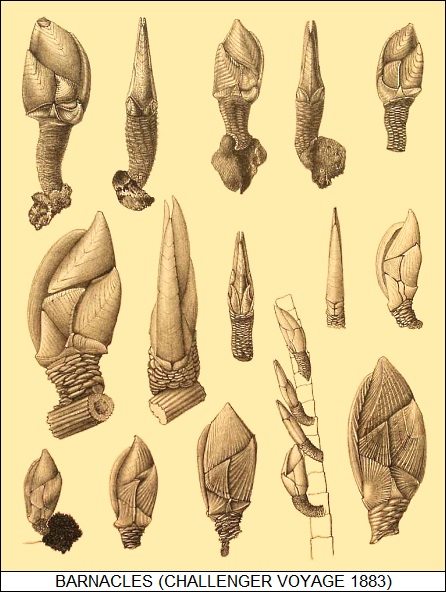

He continued his research, including an eight-year effort to perform a definitive study of the cirripedes -- barnacles. Darwin had been to that time something close to the stereotype of the gentleman naturalist, bright and interesting to his scientific community, but still something of a dabbler. He wanted to perform a serious, exhaustive research effort to demonstrate credibility to the scientific community -- and besides, examination of a single family of creatures in maximum detail would give him more ammunition for his ideas about natural selection.

Barnacles, incidentally, provided Darwin a good set of examples for his evolutionary thinking. Although such sedentary ("sessile") creatures might be assumed to be mollusks, related to clams and the like -- they once were, that's how Linnaeus classified them -- in fact, they are a family of crustaceans, related to crabs, lobsters, and shrimp. A larval barnacle is a free-living organism that looks much like a larval shrimp; even after it matures and settles down, there is a shrimp-like creature embedded inside its shell, head to the bottom, its fringed feet waving back and forth for food.

It didn't seem hard to see that the barnacle's ancestors had been free-living organisms along the lines of a shrimp that adapted to a sedentary lifestyle not so different from that of a mollusk. There is also a wide range of variation among barnacles, with the family including parasitic forms that infect other crustaceans that actually resembled a fungal infection, sending tendrils out through its host.

In any case, Darwin got as much exhaustion as he might have ever wanted out of this research effort, examining about 10,000 barnacles in the course of his work. He wrote in 1852: "I hate a Barnacle as no man ever did before ... " He finally completed the effort with an enormous sense of relief in 1855, and published two volumes describing his research.

He then went on to a series of detailed experiments on how organisms might propagate to remote lands -- for example, observing how seeds and the like could float in salt water or reside in the digestive tract of a bird, and still germinate. He also started raising pigeons as an experiment, only to fall in love with the birds and become an enthusiastic pigeon-fancier, engaging in contacts with the extensive network of British pigeon-breeders.

BACK_TO_TOP* By the end of 1857, Darwin had been tinkering with evolutionary ideas for two decades, but even then he didn't feel ready to go public with natural selection. He had distributed his preliminary draft on the subject to close friends and correspondents, including Sir Charles Lyell, who Darwin greatly admired; Sir Joseph Hooker (1817:1911), a well-known botanist; and Thomas H. Huxley (1825:1895), a biologist. Reactions were mixed. Lyell did accept that evolution occurred, but had problems buying off on natural selection. Huxley was more impressed, telling Darwin: "How extremely stupid of me not to have thought of that!"

Huxley tried to persuade Darwin to stop sitting on his work, saying that he was likely to be trumped by somebody else if he didn't. Just as today, in those times priority of discovery in scientific research went to whoever published first. Darwin was still in no hurry. He wanted to build a huge, definitive, multivolume work to make a solid case for evolution by natural selection -- but then a wild accident of chance intervened.

Darwin had been corresponding with Alfred Russel Wallace (1823:1913 -- note the unusual spelling of his middle name), a young naturalist who was then performing field studies in what is now Indonesia. Wallace was in many ways the opposite of Darwin. Darwin had been born wealthy and had never had to work for a living; Wallace was born poor and had spent much of his adult life scrabbling to get by, shooting exotic animal specimens for sale to other naturalists while on shoestring expeditions to the far parts of the globe. He spent four years on his first expedition, to South America, only to have his ship catch fire and sink with all his collection on the way back to England. The ship that rescued the crew almost sank as well before it reached port.

The only silver lining was that Wallace's agent in London had been astute enough to insure the collection for 200 pounds, a generous sum of money in those days. In any case, there was something of the incurable optimist in Wallace, and he didn't hesitate to go back to the field -- partly, it seems, because he liked it there. Darwin tended to regard native folks as savages; Wallace tended to mingle in with them, in preference to the company of white colonialists. The two men were, however, very similar in their love of the study of nature, and as it turned out in some of their ways of thinking.

Since Wallace had to make a living collecting specimens, he tended to acquire them in large numbers, and was struck by the variation among members of the same species. It is obviously true that humans vary greatly in height, body structure, hair color, and so on; Wallace saw that this insight applied to other animals. In addition, Wallace observed, as had Darwin, the way families of organisms tended to be clustered in specific regions. On reading Malthus, Wallace understood, just as Darwin had, that there was a struggle for existence that winnowed out individuals of various species, with those whose variations made them better suited for survival propagating, and those whose variations hobbled them dying out. In a cooling climate, the elephants in a population that featured more body hair would gradually predominate as those that featured less dwindled.

In short, Wallace had also discovered natural selection, and wrote his ideas up in a short, tidy paper while he was suffering from a fever during his distant travels. In early 1858, he sent the paper to Darwin so that he might review it, and pass it on to Sir Charles Lyell if it seemed to have merit. On reading the paper, Darwin was mortified, writing Huxley: "Your words have come true with a vengeance that I should be forestalled."

Darwin passed the essay on to Lyell as requested, and went into a huddle with his scientific colleagues to determine what he ought to do. The solution was for Darwin to present two older papers he had written on natural selection -- but never released publicly -- along with Wallace's paper to the Linnaean Society of London, an organization of naturalists. The papers were presented on 1 July 1858; the whole arrangement was a bit dodgy but Wallace, an easy-going sort, swallowed whatever annoyance he might have felt and only recorded his pleasure at being given such consideration by prominent scientists. Wallace clearly recognized that Darwin was literally years ahead of him in nailing down the details; Darwin would get the star billing, and Wallace was content at the recognition that filtered down to him. At least it spared his name all the abuse that would later be heaped on Darwin's.

* Incidentally, both Darwin and Wallace had been trumped on the discovery of natural selection by four decades and didn't realize it. In 1813, an American-born scholar named William Charles Wells (1757:1817) published a paper in which he pointed out that dark-skinned folk were better acclimated to tropical climates. He believed this was due to the fact that the darker members of the population were more likely to survive and propagate than the lighter members in hot, sunny tropical conditions.

Darwin himself couldn't have put it more neatly. However, Wells hadn't made very much of a case for the idea, only suggesting it as a mechanism for the emergence of dark skin color, not proposing it as a general principle for the emergence of species. His paper didn't make much of a splash and was forgotten -- though Darwin would eventually learn of it and, fussily conscientious as always, ensure that credit was given where it was due.

Modern research into the literature of early naturalists also shows that James Hutton came up with the core idea of natural selection in a work published in 1794, but Hutton wasn't a particularly clear writer to begin with, that particular book was little read, and there's no evidence that Darwin ever came across it. In any case, the fact that there were predecessors to Darwin's work should not be interpreted as belittling Darwin's contributions: the work before Darwin was on the order of fantastical sketches of flying machines, while Darwin's accomplishments were on the order of building an airplane and flying it from London to Paris.

BACK_TO_TOP* Darwin's 1858 presentation on natural selection to the Linnaean Society was hardly a bombshell. In fact, few paid much attention to it, likely because it had just been thrown out briefly as an idea without much backup to validate it and demonstrate its implications. Darwin followed the presentation of the papers with a little over a year of energetic work on a much more complete exposition of his ideas, something that would do a proper job, though it wouldn't be the excruciatingly detailed multivolume work that he felt was really required.

The book was published on 1 November 1859 under the title of ON THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES BY MEANS OF NATURAL SELECTION. Not surprisingly, it became known by the simpler title of THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES. Darwin presented his argument in a well-structured fashion, working through the basic elements of the theory:

The evidence for variation under domestication was obvious. As Darwin showed, humans had long exploited the malleability of organisms to raise new breeds of dogs, domestic animals, and crop plants through selective breeding. He chose as a particular example his beloved pigeons.

He also pointed out that there was a considerable variation of species in

nature. Although there was no immediate evidence to believe the malleability

of life in the wild was as great as that in domesticated breeds, there were

obviously related families of organisms, such as the barnacles Darwin knew

so painfully well, that exhibited a great deal of diversity. In addition, he

noted that species tended to exhibit local variations, with experts able to

tell what locale a particular specimen was from. This was the case with the

Galapagos tortoises, which were distinct to each island.

* That said, he presented his notion of natural selection. The ideas of Thomas Malthus suggested that organisms propagate at a rate that would cause them to outstrip their food supply, unless their numbers were checked. That led to the core concept of natural selection, that those species whose variations gave them an advantage in the "struggle for existence" would survive and prosper, while those that didn't would die out. It was a simple idea, a mere suggestion that natural forces could perform selection that led to new forms of organisms, just as an animal or plant breeder used selective breeding -- artificial selection -- to obtain new forms.

Along with the notion of natural selection, Darwin also introduced the concept of "sexual selection". The elaborate tailfeathers of a peacock obviously served no useful purpose for individual survival and were hard to explain. However, since only males had the fan of tailfeathers, that suggested that sex had something to do with it. Under sexual selection, peahens were attracted to peacocks with more elaborate tails, and so peacocks with bigger tails tended to propagate more than those with smaller tails, ultimately leading to a riot of elaboration. Even at the outset Darwin realized that simple individual survival -- the ability to catch prey or the ability to avoid becoming prey, the ability to survive on available food, the ability to fight off disease and stand extremes of climate, or in other words the obvious elements of the "struggle for existence" -- wasn't all there was to the matter.

For example, he observed the interdependence of flowers and pollinating insects such as bees, with each unable to survive without the other -- what in a later time would be called a "mutualistic" or "symbiotic" relationship, implying that the two lines had "co-evolved" in a mutual fashion. Bees also often had a hive organization in which the death of an individual, such as the death of a bee after using its stinger against an enemy, would contribute to the survival of the hive as a whole. In more general terms, Darwin pointed out that "selection may be applied to the family, as well as to the individual" -- a concept which would turn out to have subtleties that proved troublesome to work out, but which is now acknowledged as "kin selection". Darwin realized at the outset that there was more to natural selection than simple brute competition.

In any case, evolution by natural selection implied that variations in a species isolated from each other by geography or habit would gradually diverge into two separate species, and that the overall history of species could be diagrammed as a branching tree, with similar species arising from recent branches and less similar species arising from older branches. The tree was often "pruned" as emerging species pushed aside established species. As the fossil record showed, species often went extinct and died out, and the same process could be seen in the actions of "invasive species" that were introduced to remote lands, to then drive local competitors to extinction.

Darwin emphasized that natural selection was a very gradual process, that the changes in a species would happen by slow degrees, generally not perceptible from one generation to the next. Natural selection was also necessarily opportunistic and lacking in vision: the only changes that would be promoted would be those that provided an immediate advantage, however slight, with changes advantageous only over the long term going nowhere. To be sure, changes that neither harmed nor aided the fitness of a species could be carried along, though they wouldn't be tuned by selection. Darwin pointed out examples of intermediate forms of adaptations he had come across to reinforce the notion of gradual change -- for example, a poisonous snake he had seen in South America that would shake its tail to make noise by thrashing the ground, even though it had no rattles on its tail. Rattlesnakes had moved on from this behavior to sport modified scales on the tail that generated a distinctive rattling sound.

* Darwin noted that the way different species varied often followed clear patterns. For example, cave-dwelling fish obviously derived from fish from the outer world generally lost their eyes, such organs being irrelevant to survival in continuous darkness, in fact a liability because of their vulnerability to injury and infection. Evolution, in its short-sighted way, simply threw the eyes away even though they were something that might come in handy in changed circumstances. It wasn't a question of all the blind creatures being related, either, because in many cases they were clearly from different stocks.

Another aspect of the case Darwin made was the flexibility of life. Why were there woodpeckers in South America that lived on the pampas, where there were no trees? Why were there crabs on Indian Ocean islands that ate coconuts, with specialized claws to tear them open? He certainly found a wild variation in function among the barnacles, which also had the surprising feature of looking like mollusks on the outside but looking more like shrimp under dissection. If these creatures had all been designed, their forms were arbitrary; they only fell into a perceptible pattern with the assumption that they had arisen through a branching process following purely opportunistic paths.

He was also fascinated by the patterns of instinct, which in insects and similarly unintelligent beasts was invariably inflexible and unchanging -- what in our modern age would be characterized as robotic, executing as commanded by a fixed program. Darwin felt that natural selection could also account for the instincts of creatures, such as ants, that nobody would think capable of anything resembling real thought.

In addition, instincts covered a wide range of variability, just as natural selection might assume, with Darwin pointing to the wide variation in the structure of bird's nests as a bit of evidence. He used as another example the neat hexagonal honeycombs of most honeybee hives, describing a Mexican bee species that didn't produce such a neat structure, as if it were lower on the evolutionary tree of instinctive behaviors. Along the same lines, he observed that paper wasps also built nests full of hexagonal cells -- but made of paper, not wax, which suggested the "parallel" evolution or at least modification of the concept in the two different species. However, he was careful to say that there was much that needed to be learned about paths of natural selection, and that scientists should not jump to conclusions about the paths of evolution without robust evidence.

* Darwin acknowledged that the geological record for the evolution of life was necessarily sketchy, but he also pointed out that the fossil record clearly demonstrated a succession of forms consistent with an evolutionary concept. Darwin insisted that organisms would evolve by small and usually indistinguishable steps, rejecting the idea that it happened in abrupt transitions. This concept of abrupt emergence, known as "saltationism", essentially asserted that an individual of one species would give birth to individuals of a new species.

There is a simple and immediate objection to the idea: where is an organism with sexual reproduction that has emerged in one big step going to find a mate? Worse for the notion, while the variations from generation to generation of an organism may be abrupt and drastic, when they are drastic, they usually result in monsters. The variations are usually much subtler, even all but un-noticeable, with natural selection tuning the changes over the generations.

Although a minor change in the coloration of an animal might, or might not, be a benefit to it, completely changing its coloration at random is unlikely to help. A simple doubling in size, without the needed complementary modifications of the organism, is not likely to give it any advantage -- human giants, the result of thyroid gland malfunction, are impressive but live uncomfortable and short lives, humans not being adapted to be that big. Taking a small step in the dark is likely to work out much better than a big leap.

Darwin famously said in chapter 14 of THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES that "natura non facit saltum" -- "nature does not make leaps". Saltationism is like rolling a hundred dice in a shaker and expecting to have them all come up 6. That would happen, on the average, over an interval that would make the lifetime of the Universe seem like the blink of an eye. Evolution is more like rolling a hundred dice and setting aside every die that comes up 6, then rolling the remaining dice again until there are no dice left. That might take an hour.

* Darwin also pointed out that the geographical distribution of species was consistent with evolution. For example, why were there distinct and easily distinguishable groups of monkeys in South American and Afro-Asia? It seemed that the two groups had split off at some time in the distant past and branched out along two different paths, what Darwin called a "principle of divergence".

This phenomenon was particularly striking in the case of isolated islands like the Galapagos. In the first place, the islands were only home to organisms whose ancestral forms could have survived an ocean-crossing journey: birds and some reptiles, but no large mammals. In the second place, these organisms were clearly related to organisms found on the nearest land mass. In the third place, even among the island group, organisms on each island tended to visibly differ from their cousin organisms on the other islands, as if the set of organisms on all the islands were evolving along different branching paths.

Darwin added that the organizations of organisms into clearly related families as established by Linnaeus was absolutely consistent with the concept of evolution by natural selection, with the mechanism clearly accounting for the branching paths of that organization. The homologies between closely-related species were particularly intriguing, since they demonstrated common structures being wildly adapted to different purposes. He also pointed to the transitions in the development of embryos to show that they hinted at past relationships to other creatures -- for example, at some point in its existence a human fetus has a tail -- and the fact that many creatures had "vestigial" organs, for example the rudiments of rear legs in the whale.

* THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES did admit there were difficulties to the idea, such as the existence of complicated and highly refined organs that would seem unlikely to have arisen by a such a scheme; the incompleteness of the fossil record available to him in determining transitional forms; and the lack of known mechanisms by which changes occurred in individuals and were passed down to descendants. Darwin's vague discussions of hereditary mechanisms were the least satisfactory part of his argument. He did not feel these were fatal problems, simply issues that needed to be addressed farther down the road.

As far as the evolution of humans from other organisms went, Darwin did nothing more than hint at the possibility in THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES, since he knew that would be controversial, and so he wanted to make sure he did an adequate job when he addressed the issue in earnest. As far as the origins of life itself, that was basically out of his domain of concern, though he did privately and briefly speculate on how it might have happened.

THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES is a painstaking, thorough, plodding work. It is not a stimulating read for most modern readers, and it says something about Darwin's insistence on nailing down the details that he actually wanted to write something much bigger, more definitive, and no doubt even more eye-glazing. In fact, its very plodding nature was the key to its importance: Darwin had clearly done his homework, and THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES was too formidable to be dismissed.

BACK_TO_TOP* Although Darwin's 1858 presentation to the Linnaean Society had been ignored, THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES was not. On the day after Christmas 1859, the normally conservative TIMES OF LONDON published a glowing review of ORIGIN OF SPECIES. Darwin didn't know at the time that the author was his correspondent T.H. Huxley. Darwin hadn't told Huxley too much about the theory before the presentation to the Linnaean Society the year before, but Huxley found Darwin's thinking sparkling.

Huxley didn't agree with Darwin in all the details, in particular backing saltationism and suggesting to Darwin that he shouldn't have even touched the issue of the origins of life, but THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES still held immense appeal to Huxley. Darwin was retiring in demeanor and reluctant to rock the boat; Huxley was charismatic, aggressive, and very much a bomb-thrower who wanted to upset the established order. Huxley had been born poor and worked his way up to a position of scientific respectability. Not surprisingly, he tended to resent the wealthy gentlemen-scientists who held such influence in the forums of science. However, Darwin was an exception, particularly because he had given Huxley a lever to use against the conventional scientific wisdom of the time.

There were others beside Huxley who were impatient with the old ways and wanted change. Huxley was their natural leader, a fiery prophet to spread the teachings of Darwin. Huxley was actually looking forward to war, writing the master that as for the "curs that will bark and yelp" Darwin should realize that he had friends with an "amount of combativeness" that will "stand you in good stead." Huxley concluded with anticipation: "I am sharpening my claws and beak in readiness."

Huxley joined with Hooker, Lyell, and the American Asa Gray (1810:1888) to create what was called the "Four Musketeers" in defense of Darwin -- though Gray, a devout Presbyterian, eventually created a theistically-flavored view of evolution that the others weren't entirely comfortable with. As Gray saw it, there was certainly common ground in the thinking of Charles Darwin and John Calvin: did not Calvin believe that only a small number were chosen for salvation while the rest were damned? What really was the difference between that and natural selection? Certainly Gray gets credit for trying to reassure believers about evolutionary science, though his efforts would not prove particularly successful. Darwin had given creationism a blow that would prove fatal as far as its standing in the sciences went, but even in the present day, religious soreheads cling tenaciously to creationism and paint Darwin as a villain.

Huxley was correct in his belief that there were those who were inclined to "bark and yelp". Owen was one of the first, publishing a scathing review of THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES in a newspaper in April 1860. The review was anonymous, but everyone knew it was Richard Owen because of its acid style. Owen would gradually earn a level of animosity from Darwin granted to few others, with Darwin writing in a letter: "I used to be ashamed of hating him so much, but now I will carefully cherish my hatred & contempt to the last day of my life."

Partly the hostility of the critics was due to the inertia of catastrophist creationist dogma among the scientific community of the era, but Darwin's notions of the chance nature of evolution by natural selection, based on what amounted to throws of the dice and the selection of winning throws for survival, seemed like a hard thing to swallow. Worse, the implication that humans had evolved from earlier primates, what everyone called "apes". Technically speaking that was inaccurate, the ancestors of humanity were also the ancestors of modern apes, but such a nitpicking distinction was forever irrelevant: what the hairy grunting beasts were actually called, whether humans were the descendants of apes or merely their brethren, the idea that humans were another species of primate was still downright offensive, implying the rejection of the idea of the superiority of humans to all other animals. Adam Sedgwick went through THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES and wrote Darwin, in a civil but strained fashion, that he had read it with "more pain than pleasure".

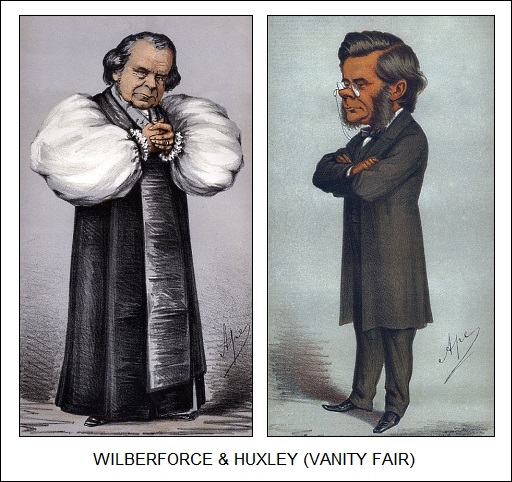

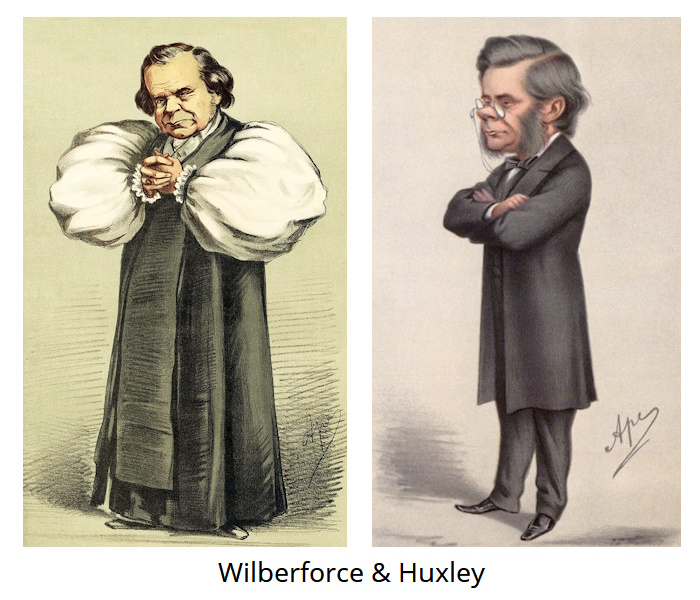

Huxley was more than willing to take on such skepticism. At the meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science at Oxford on 28 June 1860, he took on Owen in a clearly hostile argument over the similarity of the brains of humans and gorillas. The next day, Huxley conducted a debate with Anglican Bishop Samuel Wilberforce (1805:1873) of Oxford, who sneered at the concept of evolution. Wilberforce sniped at Huxley, asking if he was descended from apes on his grandmother's or grandfather's side. Huxley, who it seems had been expecting such an obvious jab and already had the response in his pocket, responded eagerly, whispering to a colleague: "The Lord has delivered him into mine hands." -- and then standing to reply:

QUOTE:

If then the question is put to me would I rather have a miserable ape for a grandfather or a man highly endowed by nature and possessed of great means and influence, and yet who employs those faculties for the mere purpose of introducing ridicule into a grave scientific discussion -- I unhesitatingly affirm my preference for the ape!

END_QUOTE

The crowd roared with laughter. The devout Captain FitzRoy was in the audience; he had come to Oxford on other business and then decided to attend the meeting. He stood up and declared to the audience that reading THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES had given him "the acutest pain" and, waving a bible over his head, told them that they should believe in God, not man. He was jeered down; Sir Joseph Hooker followed in the meeting by stating that Wilberforce had never read THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES and knew nothing about botanical science. Hooker wrote Darwin that "the meeting was dissolved forthwith, leaving you master of the field."

Huxley emerged from the meeting as the master's disciple, with his reply to Wilberforce making history -- as well as confirming the tone of sniping and trading of insults characterized by the war of extremists against evolution from that time on. Huxley never felt apologetic about it, either. In 1873 Bishop Wilberforce fell from a horse, struck his head, and died, with Huxley providing an uncharitable epitaph: "For once, reality came into contact with his brain, and the result was fatal." Such was Huxley's aggressiveness that he became known as "Darwin's bulldog".

* As a footnote, one of the interesting incidents in the early days of feuding over evolution was an attempt by a British naturalist named Philip Henry Gosse (1810:1888) to create what he believed to be the perfect compromise between science and religion. His book OMPHALOS: AN ATTEMPT TO UNTIE THE GEOLOGICAL KNOT was actually published in 1857, before the publication of THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES, with the intent of reconciling the evidence for an old Earth with scriptural determinations of a young Earth -- but the basic idea was just as applicable to evolutionary theory.

What Gosse proposed was that the evidence for an old Earth was all correct, but the Earth really was young: it had simply been created to look old, with fossils and geological strata in place at the outset. The world, in this concept, was something like a medieval castle built by Disney, implemented carefully to look exactly like a real medieval castle. The term "Omphalos" was Greek for "navel", a reference to the notion that Adam and Eve had been created with navels despite the fact they'd never had a birthcord. The Earth, according to Gosse, had similarly been created with a vestige of a history that never really happened.

Gosse was apparently shocked at the violence of the rejection of the idea, one publication calling it "too monstrous for belief". To the devout, it made the Creator a "cosmic prankster" who had created false clues to trick humanity. To the scientific, it acknowledged that the evidence for an old Earth (or, by implication, evolution) was valid -- but then tried to invalidate it by claiming without any justification that it was all a fabrication. It was a joke, a completely arbitrary and useless contraption, capable of explaining any and all observations of the real world with the glib and uninformative declaration of: "It was just made that way."

One could as easily claim that the entire Universe had been created last Thursday, with all evidence and memories of the past fabricated at that time, and defend "last Thursdayism" as just as valid as, in fact basically the same as, "Omphalos creationism". It was unfortunate that Gosse, an excellent marine biologist and in fact one of the inventors of the modern salt-water aquarium, went down in history for such a flimsy idea. The notion of Omphalos creationism still persists in 21st-century creationism at a background level, though it's clearly a tactic of desperation. Certainly, modern conspiracy theorists, with their habit of dismissing inconvenient evidence by declaring it a fabrication, end up seeming petty and timid in comparison to Philip Henry Gosse.

BACK_TO_TOP