* In classical times, the general assumption was that all the species of plants and animals on the Earth had been established at Creation, a few thousand years ago. It wasn't until the late 18th century and early 19th century that scholars began to wonder if the processes that seemed to geologically reshape the Earth didn't imply a world that was very old and always in a state of change.

Ideas that species might also have been around for a long time and were in a continuous state of change -- having "evolved" in other words -- arose in parallel, and were boosted by the discovery of long-lost beasts of the past, preserved as fossils. Such speculative ideas were neither well thought out nor well accepted. The first nudge on a process that would change the status quo began in late 1831, when a young English gentleman naturalist named Charles Robert Darwin departed Britain on a small Royal Navy research ship, the HMS BEAGLE, for a five-year voyage around the world. On his return, Darwin settled into the family life and began to investigate the ideas he had picked up on his journey.

* Before the era of modern science, the general belief in the West was that the Earth had been around for a few thousand years, with all the creatures created at the start and remaining unchanged to the present day. There was a belief in what was called the "Scala Natura (Scale of Nature)", in which the organisms of the world were arranged in a scale of increasing refinement, with, the earth at the bottom, plants above that, then the beasts, with humans at the top of the Earthly hierarchy -- but beneath the angels. This arrangement did not imply any relationship between the various levels of the scale other than one of rank, the notion being no more that there was "a place for everything and everything in its place." The ranks had been fixed at the Creation and would remain fixed until Judgement Day.

It wasn't until the beginnings of modern science that this static mentality began to erode. The voyages of discovery conducted by Europeans from the 15th century on led to an explosion of knowledge about the plants and animals of the Earth, and in the 18th century, the Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus (1707:1778) took on the task of cataloging them all.

In the "Linnaean" system, organisms were organized as distinct "species", or different animals that couldn't interbreed, sometimes with a number of "breeds" or "races" or "varieties" (the last term generally meaning plants) associated with a single species. There were corner-cases as well, for example crossbreeds or "hybrids" between species that were sterile -- such as mules, which were a cross of a horse and a jackass. A number of species could be organized into a "genus" (for example, the genus of cats or "felines"); with a number of genera becoming an "order" (felines, canines, bears, and the like becoming the order of "carnivores"); a number of orders becoming a "class" (carnivores, rodents, primates, and so on becoming the class of "mammals"); and classes becoming members of "kingdoms" (either "animal" or "plant").

Linnaeus was not the first to attempt such a classification, but he was the one who prevailed, his work bolstered by his excellent writing skills, his charismatic ability to influence others, a global network of naturalists feeding him information, and an obsessive thoroughness. The Linnaean classification system, with its scheme of Latin names for organisms (Canis lupus for "wolf", for example), remains in effect to this day, with some additions -- such as subdivisions of the kingdom of animals and plants as "phyla" (the class of mammals being organized with reptiles, birds, fish, and amphibians as the phylum "vertebrates", or creatures with spinal cords). Sometimes plant phyla are referred to as "divisions".

There was little in the system of Linnaeus that contradicted the long-standing notion that species had been created in the past in the same form as they existed in the present, though late in his life he seems to have had some vague questions about things. His neat categorization of different species, which by modern standards was remarkably if not close to perfectly accurate, might well have led someone surveying the Linnaean organization "tree" to ask the question: why do these tidy familial groupings exist? Why should there be families of cats, of owls, of bats? What was particularly confusing was that there were equivalent organisms in different families, for example insect-eating bats and insect-eating birds, or sharks and mammalian dolphins. If they had been created, why the duplication? Indeed, if species had been created, why such a wild diversification over such a range of variation? Why so many different species of beetles?

During this era of the "Enlightenment", some people were asking such questions explicitly. The French naturalist George-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707:1788), presented a new vision of the past history of the Earth in his monumental NATURAL HISTORY, published in many volumes from 1749 to 1789. Buffon suggested that the Earth and the planets were born from a catastrophe that threw material off from the Sun, with life then arising spontaneously on Earth as the planet cooled. Buffon also suggested that modern species were derived from different ancestral species. This was clearly proposing the evolution of species, though Buffon was very limited in his proposal, saying that, for example, all the different species of cat were derived from one ancestral species of cat, with no connection between the evolutionary tree of cats and the corresponding tree of wolves and dogs. As far as how or why this evolution occurred, Buffon could only offer speculations on what he called "internal moulds" that guided the direction of this evolution, ideas that sound fuzzy now.

In fact, evolutionary ideas along such lines were something of a fashion among the intellectuals of the Enlightenment. The French encyclopedist Denis Diderot (1713:1784) actually foreshadowed modern evolutionary thinking by proposing that the variations in species were strictly random, though he proposed that life arose through spontaneous generation, and that change was driven by what we would now consider to be some sort of "life force". The concept was later referred to as "vitalism", envisioning that there was something more to life processes than could be explained by the laws of physics and chemistry -- an "elan vital" or "life force" as it was once called. Vitalism was not a blatantly unreasonable idea at the time, since nobody could even imagine the complexities of biochemical reactions as they are now understood, but in hindsight vitalism seems less an explanation than a non-explanation, simply throwing up one's hands and declaring the matter an unexplainable mystery.

A prominent British physician named Erasmus Darwin (1731:1802) published a text titled ZOONOMIA in 1796 that proposed a form of evolution of species, though it was hardly scientific in its description. In fact, Erasmus Darwin was something of an eccentric, given to writing odes to free love and in praise of sex. It would fall to one of his descendants to do a proper job of things.

The Enlightenment ended up being something of a frontal assault on conventional thinking, or at least the critics could interpret it as such. The violent excesses of the French Revolution helped discredit attacks on authority by the intellectuals of the Enlightenment, and the generation of thinkers that followed tended more towards the reactionary. Georges Cuvier (1769:1832) was Buffon's intellectual successor in French naturalism, though absolutely not his heir. Cuvier used his undoubted brilliance and his powerful position in academia to emphatically reject evolution, insisting that as per tradition the species were fixed, having been created and then remaining unchanged to the present.

A later age would see Cuvier as on the wrong side of the argument, but in fact the evolutionary musings of the era were vague and not backed up by much serious observation or experiment. Nobody could now consider their ideas as particularly scientific; their assault on tradition also tainted their ideas with radical ideologies that many found offensive, even dangerous.

BACK_TO_TOP* The idea of evolution didn't go away. A contemporary French naturalist, Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, Chevalier de Lamarck (1744:1829), proposed a theory of evolution that actually included a mechanism, something of a first. The simplest way to explain his theory, now known as "Lamarckism", is to consider the well-known example of the giraffe. As Lamarck saw it, the giraffe with its extraordinarily long neck arose from ancestors with shorter necks. In their attempts to reach the higher branches of trees, giraffes stretched their necks as far as they could; this stretched neck would be passed down to their progeny, which would have a longer neck that they stretched farther still.

In the same way, the children of a blacksmith with powerful arms would also have a powerful build, which they would enhance in turn; animals in cooling climates would acquire heavier coats of fur and then pass them down to their offspring. On the other side of the coin, unused organs would gradually wither away -- flightless birds generally had small wings useless for flying. Lamarck's theory effectively proposed a form of "directed" evolution, based on two linked ideas: that adaptations were obtained as a direct response to the "needs" and "strivings" of an organism, and these adaptations were then passed down to progeny.

In modern times, the second notion, "inheritance of acquired characteristics", is much more heavily emphasized as Lamarck's legacy than the first -- despite the fact that the idea was hardly new to him. People had long believed in inheritance of acquired characteristics, that having been the traditional folk wisdom, and in fact the idea still lingers among the unlettered today.

* Lamarckism was a superficially appealing idea, but it was, in itself, a dead end. Lamarck's notions of "heredity" -- the mechanism by which parents passed characteristics on to their progeny -- were both vague and misinformed. An organism's capabilities are essentially fixed when it is conceived. This is not to say that an organism is as rigid in structure as any machine rolling off the production line, only that heredity deals an organism a particular set of cards at the outset and its life will be a game played with those cards.

Even if an organism did acquire new biological features, it has no real means of passing them down to the next generation. That would imply the organism had some means of modifying or "editing" its heredity. This "editor" system would have to have some "blueprint" of how the organism was put together, and would have to "scan" the entire organism to see how it conformed to this blueprint. When the modifications due to the efforts of the organism to, say, stretch its neck were uncovered in the scan, the editor would have to then make the appropriate updates to heredity. This system would be extremely elaborate, and since Lamarck's time, nobody has found a trace of it.

Worse, acquired characteristics are not necessarily good; if an animal loses an eye, how would the editor know this was something undesireable? The editor would have to be able to make value judgements, determining what new features amount to improvements and which amount to defects. In addition, while it is possible to imagine a giraffe getting a longer neck by its efforts, anyone who's ever worked as a problem-solver knows that problems in themselves do not necessarily suggest obvious solutions. How could a blind creature "strive" to see?

There's a little fine print on this condemnation of Lamarckism. We do know today that we are hosts to a colony of microorganisms, most notably in the gut, and that we are in part dependent on that colony for our health. That set of microorganisms will change over our lifetime, possibly to our benefit. A mother passes on a sample of the bacteria in her gut to a baby, and so that would amount to a sort of inheritance of acquired characteristics. That in no way suggests Lamarckism was on the right track.

* Although Cuvier could not have known just how broken Lamarckism was, he did correctly see that it was broken. Since he was well-known and influential while Lamarck was not -- despite the high-flown title, Lamarck was poor and obscure -- Cuvier's views on the fixity of species carried the day for the time being. Although he can't be faulted for his rejection now, he can still be faulted for his insistence on the fixity of species, particularly because he admitted that there had been changes in species over the history of the Earth.

Fossils, the stony remains of the skeletons of ancient organisms, had been long known, but had been dismissed as the remains of freaks or monsters. Cuvier took them perfectly seriously as evidence of past life -- for example, he examined the skulls of the extinct elephants that would become known as "mammoths" and proclaimed them unarguably different from living elephants. Significantly, Cuvier identified particular types of fossils as associated with particular buried layers of geological deposits, or "strata". He still believed that nature was basically static and unevolving, that the strata were associated with distinct eras that ended in global catastrophes that wiped out species, with a new set of species created in their place. This concept became known as "creationist catastrophism" -- the Maker having implemented all the creatures of each era, and then destroyed them after their time was done.

BACK_TO_TOP* Cuvier's pioneering work on the study of fossilized species, what is now known as "paleontology", amounted to an exercise in sawing off the branch underneath his own ideas, though he would not live long enough to see the branch fall.

Scientific and public interest in fossils was high at the time. William Smith (1769:1839), a British engineer working for a canal-digging company who learned to pay close attention to what he was digging up, discovered that a particular layer of sedimentary rock could be identified by its distinctive fossils. Smith, as a working person, was not taken very seriously by the British scientific community at first, but other naturalists confirmed the notion. Smith's pioneering geological work showed that there had indeed been a succession of species through history, though as far as that went it was completely compatible with Cuvier's notion of catastrophism.

Cuvier himself was the first to identify a fossil of a great reptile, the first evidence of an age when huge reptiles dominated the Earth. A toothed jawbone well more than a meter long had been dug up from a mine near the river Meuse in the 1770s, but nobody knew what to make of it. In 1795, French troops operating in the region brought it to France, where it was passed on to Cuvier. He identified it as the jawbone of a whale-sized ocean-going reptile, apparently a species of monitor lizard, which was subsequently named Mosasaurus -- meaning "Lizard of the Meuse".

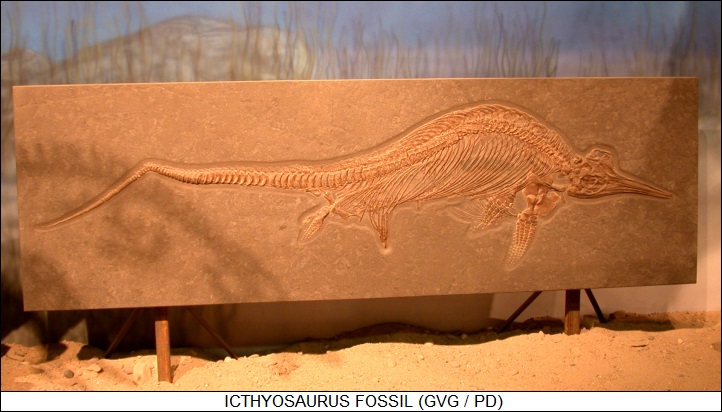

This discovery was followed by others. In 1811, a 12-year-old English girl from Dorset named Mary Anning (1799:1847) discovered the fossil of an ocean-going reptile reminiscent of a porpoise, which would be named Icthyosaurus; a fragmentary fossil of this species had actually been discovered in 1699, but nobody knew what to make of it. Anning would become a famous fossil-hunter, discovering another reptilian sea creature, a classic long-necked "sea serpent" that was named Plesiosaurus, in 1821.

William Buckland (1784:1856), a bright, lively, and eccentric don of Corpus Christi College in Oxford, England, found the bones of a big land reptile fossilized in the same strata as Mosasaurus, describing his find in an 1824 paper and calling it Megalosaurus, meaning "Great Lizard". It was a carnivorous beast almost as big as an elephant, that walked on all fours and had a nasty set of sharp teeth. In the meantime, another British naturalist, Gideon Mantell (1790:1852), was picking over the fossil bones of a big herbivorous reptile, which he revealed to the world in an 1825 paper as Iguanodon, meaning "iguana tooth".

BACK_TO_TOP* Over the following decades, fossil evidence of strange lost worlds of the past began to pile up, with the succession of such worlds increasingly obvious in the fossil record. The geologist Adam Sedgwick (1785:1873), a Cambridge don who, along with William Smith, would be recognized as one of the founding fathers of modern geology, probed the earth of Wales and characterized the strata he found. Others were engaged in similar exercises, and in 1841 John Phillips (1800:1874), a nephew of William Smith, published a scheme in which he organized the "eras" of the past as identified by the fossil species observed in the strata.

As Phillips had it, the oldest strata belonged to the "Paleozoic" era, characterized first by invertebrates and then fishes; followed by the "Mesozoic" era, characterized by reptiles, though also yielding early birds and mammals; and finally the "Cenozoic" era, characterized by the predominance of birds and mammals. Each era was divided into "periods", the organization being much like that used today. In 1845, Sedgwick wrote that there was clearly a "progressive development" of forms over eras and periods, but interpreted the sequence as evidence only of creationist catastrophism.

Sedgwick was aware of the concept that one set of forms might have evolved into another by some process. The notion of evolution hadn't died out with Cuvier, though it was clearly on the wrong side of scientific opinion in the 1840s, and Sedgwick only recognized the idea to emphatically denounce it. So did his contemporary, the great British comparative anatomist Richard Owen (1804:1892), who lit into those who proposed evolutionary views.

Owen was still a brilliant researcher who noticed intriguing relationships between different species. He observed that a human hand, a bat wing, and a whale's paddles all had the same general "five-fingered" structure, in each case adapted to a different lifestyle, and noticed other "homologies", common patterns of structure, among other animals. He flatly denied that homologies suggested evolutionary relationships, however much in hindsight they actually did, insisting that it was simply a matter of re-use by the Maker of the same "engineering concepts" in different creatures, a notion referred to as "common Design". He would energetically resist all proposals of evolution to the end of his life, and would make many enemies with the bitterness of his resistance.

* He was assisted in his efforts, at least for a time, by Sir Charles Lyell (1797:1875), another one of geology's founding fathers, though Lyell was too civil to press the case anywhere near as furiously as Owen. Lyell had started out studying to be a lawyer, but he had taken classes from Buckland, a flamboyant lecturer, and got the rock bug. Lyell was inclined towards conservatism about evolution, but in terms of geology he became something of a scientific radical, taking on the catastrophist status quo.

Lyell obtained his inspiration from the work of the Scots scholar James Hutton (1726:1797), who had rejected the idea of a catastrophic history of the Earth, instead proposing that eras of vulcanism would raise materials from underground to directly or indirectly form islands and continents -- which would then gradually settle into the Earth, to melt and provide another burst of vulcanism. He believed that the Earth lived in a "steady state", with "no trace of a beginning, no prospect of an end."

Hutton's notions were more speculative than rigorously scientific but -- Lyell, casting aside catastrophism, was inspired to flesh them out into a much more detailed scientific theory, basing his reasoning on the new geology described by William Smith, Adam Sedgwick, and others, and incorporating the "footprints" of the past as found in fossils. Lyell described his "uniformitarianism" or "gradualism" in the monumental three-volume work PRINCIPLES OF GEOLOGY, published from 1830 to 1833, which envisioned a world of vast time, cyclically reshaped by slow processes of geology.

Hutton had been an all-but-impenetrable writer, but Lyell was crisp and persuasive, bolstered by the instinct established in his legal background to make a clear and persuasive case. Gradualism eventually eclipsed catastrophism -- though many of Lyell's colleagues were reluctant to swallow his insistence that life was basically gradualist as well. Lyell based this belief on his interpretation of the fossil record, in which he emphasized similarities between species from levels of strata instead of differences, but he was fighting the consensus that there was a progression of forms, and the evidence would continue to tilt against him. Owen would characteristically light into Lyell on this matter in 1851, and the two men would end up feuding -- feuding was something of a habit with Owen.

Lyell's notions were based on a desire to deflate evolutionary ideas, but like Cuvier, Lyell was to an extent sawing at the branch he was sitting on. Catastrophism suggested periodic interventions by the Maker; uniformatism saw the world as quietly and endlessly shifting by slow increments through geological processes taking place in endless time. That notion of "deep time", though Lyell didn't recognize the fact at the time, also provided a stage on which organisms could themselves shift by slow increments, evolving from one form to another.

BACK_TO_TOP* Charles Robert Darwin (1809:1882) was born to a privileged English family of the town of Shrewsbury, near the border of Wales. His father, Doctor Robert Waring Darwin, was a son of Erasmus Darwin, and had married Susannah Wedgwood, daughter of the famous potter Josiah Wedgwood. The family had money and prestige on both sides of the house. Susannah bore six surviving children -- four girls and two boys, Charles being the younger of the brothers. Susannah died abruptly in 1817 at age 52, when Charles was eight years old.

Except for this tragedy, Charles' upbringing was comfortable, as the family's upper-class status might suggest. He tried at first to follow in his father's footsteps and become a doctor, enrolling as a student at the Edinburgh University in 1825, but he found the studies "intolerably dull", and observations of surgeries -- in the days before the introduction of general anesthetics -- destroyed whatever interest he might have had in it. Charles increasingly focused on his interest in naturalism, to the detriment of his medical studies.

After two years in Edinburgh, it was obvious to all concerned that young Charles did not have a future as a doctor. His father then tried to steer him down the path towards the clergy. This career path was not guided by any particular religious conviction, it was just that a life as a vicar was regarded as comfortable and suitable for a gentleman, and would give Charles plenty of time to pursue his naturalistic studies. Charles went along with the notion, beginning studies at the University of Cambridge in 1827, with the expectation that he would move on to a theological institution once he had completed his general studies at Cambridge.

There he was exposed to the writings of naturalists of the time, one prominent influence being NATURAL THEOLOGY, published in 1802 by the British naturalist and theologian William Paley (1743:1805). The Reverend Paley's NATURAL THEOLOGY suggested that the elaborations of the species of the Earth and the complexity of their organs argued for the work of an "Intelligent Designer", in the modern rendering, who had created them. Paley, for example, pointed to the complexity of the eye as an example of an object that could not have existed unless some Higher Power had specified it. He argued that if one found a watch, even if it was broken, its complexity and orderly structure would have to imply a "watchmaker", and the complexity and orderly structure of organisms similarly implied a "Divine Watchmaker".

Paley's ideas were consistent with the creationism then established as doctrine. The irony was that Paley's work was the last gasp of "natural theology"; it was an idea with notable weaknesses, which had been pointed out a half-century before Paley by the Scots scholar David Hume (1711:1776):

Darwin accepted Paley in his youth, but would later find Hume's questions far more penetrating -- Darwin eventually saying that he had "believed what I could not understand and what is in fact unintelligible."

* Charles Darwin graduated with modest honors in early 1831, going on a field trip in Wales with the prominent Adam Sedgwick that summer. On return from the field trip, he found a note from another Cambridge naturalist, John Henslow (1796:1861). Henslow had been one of Charles' academic patrons and had a deal for him. The Royal Navy survey vessel HMS BEAGLE was about to depart on a global mapping and survey voyage, and an unpaid position was open for a naturalist.

The job had a flip side, in that Charles was to be a dinner companion for the vessel's captain, Robert FitzRoy (1805:1865). A Royal Navy officer had to remain aloof from and superior to his subordinates, which made for a somewhat lonely and miserable existence -- the previous captain of the BEAGLE had shot himself. The FitzRoys were prone to depressions, suicides were not unknown in the family, and Captain FitzRoy needed to have a person on board of appropriate social station to converse with lest he gradually go off the deep end. The fact that this was a real concern would be demonstrated when FitzRoy finally slit his own throat with a razor decades later.

Robert Darwin, a conscientious but domineering father -- he was a huge walrus of a man, Charles would say his father was the biggest person he ever met in his life -- had been concerned about young Charles' lack of direction, scathingly saying in an outburst of temper that his son "cared for nothing but shooting, dogs, and rat-catching" and would end up becoming "a disgrace to yourself and all the family" in a letter. Robert's concerns about his spoiled children had a basis in fact; Charles' elder brother Erasmus, named after his famous grandfather, had been following a life of idle socializing, and that was all he would accomplish to the end of his days. Robert worried at first that Charles was going off on yet another useless tangent, and one that could be uncomfortable and possibly hazardous as well.

In the face of his father's opposition, Charles turned the offer down, though Robert Darwin told Charles that the recommendation of "any man of common-sense" would alter the case. Charles found that common-sensible man in the form of his uncle, Josiah Wedgwood, son of the famous Josiah Wedgwood, who persuaded Charles to stick to his guns and backed him up. Robert Darwin caved in -- he was overbearing, but basically an indulgent parent. Charles signed up for the voyage; FitzRoy had second thoughts about taking him on, but Charles, a soft-spoken and pleasant young man, fully won him over. The BEAGLE departed England on 27 December 1831; the journey was planned to last two years, but it would not return for five years and three days.

Charles took along with him a stack of books recommended to him by Sedgwick. At the outset of the voyage, Charles believed in the current orthodoxy, his faith resting on the Bible; like Sedgwick, Charles believed in the doctrines of creationist catastrophism, and his views on the origins of the species of the world were along the lines of those of the Reverend Paley. However, Captain FitzRoy, a naturalist himself, gave Charles a copy of the first volume of Lyell's PRINCIPLES OF GEOLOGY. It would make a big impression on Charles Darwin -- he would acquire the other two volumes while on his world trip -- and help set off a chain of thought that would alter history. FitzRoy would live long enough to regret his gift.

BACK_TO_TOP* The BEAGLE's voyage was intended to collect information, and so it was basically unhurried, lasting far longer than planned. It did not start off well, with Darwin suffering badly from seasickness, an affliction he would never completely overcome. A stop in the Canary Islands was unprofitable due to quarantine that kept the crew on board the ship.

However, a layover in Cape Verde Islands proved interesting. Darwin was absolutely fascinated by the geology of Saint Jago, the largest of the Cape Verdes, with a sea cliff on the island featuring a uniform white stripe, consisting of a bed of corals and seashells sandwiched between volcanic layers. Darwin saw it as evidence for Lyell's gradualism; his faith in catastrophism began to erode.

The BEAGLE finally reached Bahia, Brazil, where Darwin drank in the riot of color and life in the South American jungles, finding the diversity of plants and animals fascinating. He spent ten weeks in a cottage in Rio de Janeiro, collecting samples and making notes. One of the things he took serious note of was the local practice of slavery -- which appalled him, antislavery sentiments having been the custom of the Darwin family.

In July 1832, the BEAGLE arrived at Montevideo, Uruguay, where a local revolution was in progress; there was no going ashore until the squabbling died down. The BEAGLE's business finished there, the vessel moved down the Argentine coast, where Darwin examined the strata of exposed cliffs. The strata were so deep that it would clearly would have taken a long, long time to lay them down; if there were cataclysms capable of such exertions, it would be hard to understand why the strata were so neat, with few disruptions.

By the end of 1832, the journey had moved on to the Straits of Magellan, but the weather was foul and the passage risky, so the BEAGLE remained in the area on its survey mission. The ship made landfall on Tierra del Fuego, returning three locals that Captain FitzRoy had more or less kidnapped on a previous voyage to the region and taken to England. Darwin found the native Fuegans the most impoverished and brutish folk he had ever seen or would ever see, walking around naked in the worst weather, and eating whatever they could kill or scavenge, such as the rotten carcasses of whales that had been washed ashore.

One of the three Fuegans who had gone to England, known as Jemmy Button after the price that had been paid for him, told Darwin that when things got desperate -- an unpleasant notion since "normal" conditions for the Fuegans were nasty enough -- the locals would kill and eat their old women, even before they would kill and eat their dogs. After all, the dogs were valuable, the old women just so much dead weight.

There is now some fair suspicion that Jeremy Button was pulling Darwin's leg, others more familiar with the Fuegans not having seen evidence they actually ate old women. Whatever the truth, Darwin judged them "savages", thieves and cannibals, not much removed from beasts, though he admitted that Jemmy Button seemed bright and adaptable. Still, he clearly saw in them the vision that the gap between man and beast might not be as great as he had previously assumed. He was also impressed by the way the Fuegans had adapted to their environment, once watching a near-naked woman suckling a baby in a driving storm of sleet as if nothing the slightest was wrong.

The BEAGLE finally backtracked into the Atlantic to harbor in the Falkland Islands, which had been seized by Britain that same year, and then sailed to the coast of Argentina again. Darwin went on a number of inland expeditions over the Argentine pampas in the company of colorful Argentine gauchos, who Darwin regarded as extremely courteous cutthroats, by halves admirable and appalling. There was a bitter war going on at the time between the white settlers and the native tribes; when the settlers cornered a group of natives, all the adults, men and women alike, were slaughtered, with the children carried off to be sold as slaves. The natives did much the same to the settlers when they could.

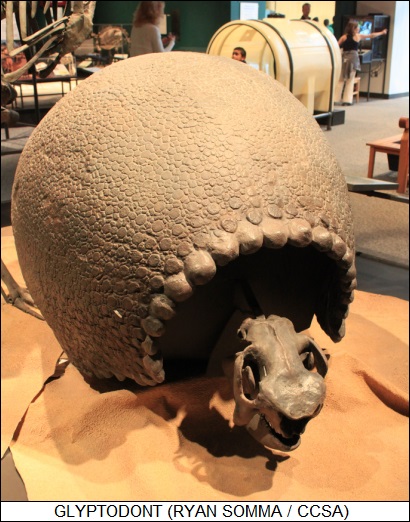

During his journeys in the region, he also took time to dig up a fossil bed. He found the skeleton of a large hoofed beast, along the lines of a rhino or hippo but not closely related to either, which would be named the Toxodon. He found the skeleton of what was anatomically similar to a South American tree sloth but much bigger, also about as big as a rhino, and ground living, which would identified as a member of the family of ground sloths or Megatheres; and a skeleton of an oversize armadillo, as big as a bear, a member of the family of Glyptodonts. He also found a fossil horse, which had existed in South America and then died out, to be reintroduced when the Spaniards arrived. Significantly, among the fossils he found remains of modern creatures: some of the beasts in the fossil bed had died out, while others continued to thrive.

By the spring of 1834, after a revisit to the Falklands, the BEAGLE was back in Tierra del Fuego. The three locals who had been taken to England had reverted to their old habits, and the environment was so unpleasant that the vessel had to remove a missionary who had been left there, lest he be murdered and possibly eaten. The BEAGLE then passed Cape Horn and sailed up the coast of Chile. There, in early 1835, Darwin observed an earthquake that badly damaged the city of Valparaiso. It was more evidence for Lyell's gradualism, with Darwin observing such changes in the terrain as the rise of a rocky shoreline, with stones still bearing barnacles lifted up from the water. He also took a trip to the far side of the Andes, in which he was bitten by insects and came down with a nasty fever.

The most significant part of the journey, from Darwin's point of view, took place in the early fall of 1835, when the BEAGLE arrived in the Galapagos Islands, well off the coast of Chile. The creatures of the Galapagos were distinctive, even unique in many ways. There were sea-going iguanas, the only sea-going lizards Darwin had ever heard of, with a similar species of iguana that lived on land. There were giant tortoises on each of the islands, with locals able to identify which island a tortoise came from by minor variations in its appearance.

Of particular importance in hindsight, Darwin described "a most singular group of finches, related to each other in the structure of their beaks, short tails, form of body and plumage ... " Some had small beaks for eating insects, some had big beaks for crushing seeds, and there was a range of variations in size. In fact, they so differed in appearance and habits that Darwin hardly thought them related; he was astonished when his samples were inspected by expert ornithologists later, and he was told they were all finches.

Darwin had been becoming increasingly convinced of Lyell's gradualism, that the Earth changed its forms in a slow and gradual fashion. His stay in the Galapagos gave him the latent seed of an idea that the same ideas might apply to species as well -- that species evolved by slow changes over time.

The BEAGLE finally departed the Galapagos for Tahiti, where Darwin found the local people attractive, gentle, and civilized. The next stop, New Zealand, introduced him to the Maoris, who he found just the opposite, judging them dirty, inclined to drunkenness and violence. On then visiting Australia he found the Aborigines there to be only about a step above the Fuegans, though he regarded them as skilled with their spears and other weapons. He observed that their numbers were in decline, and observed that this was due to the introduction of Europeans: "Wherever the European has trod, death seems to pursue the aboriginal." Indeed, when he visited Tasmania next, the locals had been all either killed or deported to a small island, where they went into terminal decline.

On the passage through the Indian Ocean he spent considerable effort investigating the reef around Keeling Island, and cooked up a general theory of the formation of coral atolls. The final leg of the voyage led to a stop in Mauritius; then in Cape Town; followed by visits to the islands of Saint Helena and Ascension in the mid-Atlantic. Darwin wanted to be home by this time, but Captain FitzRoy, examining his survey data, decided to revisit Brazil to crosscheck, so the return to England was delayed until 2 October 1836. Charles Darwin had come home, and he would never leave the country again, spending the rest of his life fleshing out the ideas that had been seeded by his trip around the world.

* Back in England, Darwin cast about in the social circles of London for a time, wrote his memoirs of the trip, and began to assemble his notes and ideas. The memoirs were published in 1839 under the title of THE VOYAGE OF THE BEAGLE, and the book was widely read. By that time, he was a member of the Royal Society of London and a well-accepted naturalist, his studies on the voyage having attracted attention, with the sponsorship of sympathetic established figures like Sedgwick and Henslow not doing him any harm, either.

The conclusion of Darwin's few years of social experimentation in London was that he ought to get married and settle down. He sounded out a first cousin, Emma Wedgwood, decided she would be a suitable wife, and proposed. She accepted and they married in early 1839. The marriage was, as was fairly common in those times, much more a practical than a romantic arrangement, the two having long known each other but never otherwise having been all that close. It wasn't quite an arranged marriage, but it was a match that was soundly approved of by the elders of both families. They would still have a close relationship; Emma would bear him ten children, three of them dying young.

With support from two wealthy families, working for a living was not necessary, and in fact Robert Darwin reassured his son that his work as a naturalist was a fine and honorable career for a gentleman; there was no need to worry about bringing in money. It would turn out to be a good, even world-shaking, investment on Robert's part. In 1842, Charles Darwin installed his growing family in a large country house near the village of Down, southeast of London, where he would continue his researches and become a pillar of the community.

BACK_TO_TOP