* As mentioned in the previous chapter, the British codebreaking operation at Bletchley Park cracked other ciphers besides Enigma. One of the most challenging was the top-level cipher used by Hitler to send orders to his senior generals, using on the Lorenz SZ-40 and later SZ-42 cipher machines.

The Lorenz machines were teletypewriter-based cipher systems. Such "telecipher" systems have some resemblance to rotor-based systems like Enigma, but are somewhat different animals. They were primitive "digital" systems, based on processing "binary" data, as are modern computers, and so pointed the way towards modern digital cipher systems.

This chapter describes the basic concepts of telecipher systems, the Lorenz machine and the British efforts to crack it, and the Colossus computer that was ultimately built to automate the decryption of Lorenz messages.

* Telecipher systems were invented during the First World War by Gilbert Vernam of AT&T and Parker Hitt, by that time a colonel. Teletypewriters were introduced early in the 20th century. They were automatic typewriting machines that could print out text messages sent over a telephone line or by radio, were an extension of 19th-century telegraph technology. As mentioned, teletypewriters used a digital transmission scheme, with two different electrical signals sent to represent a binary value of "1" or "0", or what is now known as a "bit" of information.

Multiple bits can be sent to represent sets of values greater than 1 or 0. For example, two bits can represent four values, from 0 to 3:

: 00 = 0 01 = 1 10 = 2 11 = 3

Three bits can represent eight values, from 0 to 7:

: 000 = 0 001 = 1 010 = 2 011 = 3 : 100 = 4 101 = 5 110 = 6 111 = 7

For every added bit, the number of patterns that can be represented is multiplied by a factor of two. Four bits can represent sixteen values, five can represent 32 values.

Teletypewriters used a five-bit code, known as the "Baudot" code, to represent different characters. The Baudot code was basically invented by a Frenchman named Emile Baudot in 1875 as an improvement on Morse code. It appears that Baudot's code was substantially revised by others before it came into actual use, but it still bears his name. While five bits should only be able to encode 32 characters, two of the characters are reserved to "shift" between two sets of characters, much like the modern "Caps Lock" key on a typewriter or computer. This allows the Baudot code to provide a larger set of printable characters, along with characters to perform teletype control functions.

Five of the Baudot codes are interpreted in the same way, no matter what the shift setting is. These codes include those to perform the shifts:

: 00000 NULL "Null" character, defining idle teletype output. : 01000 CR "Carriage Return", move printing to left margin. : 00010 LF "Line Feed", roll paper up one line. : 11111 LTRS "Letters", shift to letters. : 11011 FIGS "Figures", shift to numbers & figures.

The rest have one of two meanings, depending on whether the "LTRS" or "FIGS" character has been sent previously:

: LTRS FIGS : ---------------------- : 00100 space : 00011 A - : 11001 B ? : 01110 C : : 01001 D $ : 00001 E 3 : 01101 F ! : 11010 G & : 10100 H STOP "STOP" indicates end of message. : 00110 I 8 : 01011 J ' : 01111 K ( : 10010 L ) : 11100 M . : 01100 N , : 11000 O 9 : 10110 P 0 : 10111 Q 1 : 01010 R 4 : 00101 S BELL "BELL" causes the teletype bell to ring. : 10000 T 5 : 00111 U 7 : 11110 V ; : 10011 W 2 : 11101 X / : 10101 Y 6 : 10001 Z " : ----------------------

The Baudot code was one of the first binary codes used to define text characters; it has been followed by other code schemes. The best-known modern standard is known as "ASCII (American Standard Code For Information Interchange)". ASCII is an 8-bit coding scheme commonly used in modern computers; traditionally it was effectively a 7-bit code, covering 128 standard characters, along with an alternate set of 128 characters that could vary by platform or by region. ASCII is an effective subset of a 16-bit scheme known as "Unicode", which more or less covers the world's character sets.

* In any case, a telecipher machine scrambled Baudot codes using what was known in the old days as "modulo-two arithmetic" and is now known as an "exclusive OR" or "XOR" operation. The basic rules of the XOR operation are as follows:

: 0 XOR 0 = 0 : 0 XOR 1 = 1 : 1 XOR 0 = 1 : 1 XOR 1 = 0

In simpler terms, if two bits that have the same value are XORed, the result is always a "0". If two bits that have a different value are XORed, the result is always a "1". Binary values made up of multiple bits, such as the five-bit Baudot codes, can be XORed on a bit-by-bit basis:

: val1: 10011 : val2: 00110 : ----- : result: 10101

Why the XOR operation was described as "modulo-2 arithmetic" is explained in the next chapter and can be ignored for now. Note that if a given value is XORed with a number of different binary values, no two of the different values will give the same result value. In other words, information will not be lost by an XOR operation.

An XOR operation was easy to implement with the electromechanical switches available at the time. Suppose we have a number of electromechanical switches that have two input pins for attaching electrical wiring, which we'll label "A" and "B", plus a control pin that can be wired to an electrical signal to flip the switch with an electromagnet, and an output pin.

Disregarding the specific details of the electrical signal on the control pin, we'll say that if this signal is ON, that's equivalent to a "1" data bit, and if it is OFF, that's equivalent to a "0" data bit. We'll also say that if the control pin is OFF (0), input pin A is connected to the output, and if it is ON (1), input pin B is connected to the output:

: control is OFF (0): A -> output : control is ON (1): B -> output

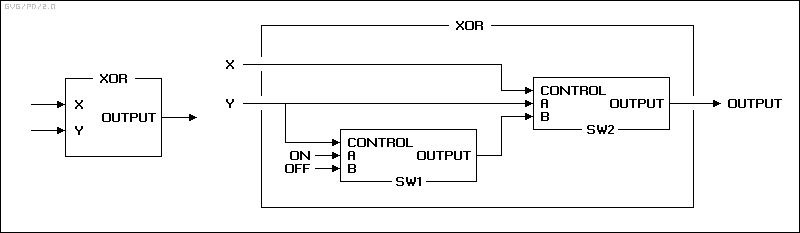

We can use these switches to build an electromechanical circuit to XOR two bits together. In modern terms, this circuit is called an "XOR gate". The input pins are named "X" and "Y" to prevent confusion with the input pins of the electromechanical switch already described. This XOR gate contains two such switches, wired as follows:

The switches are labeled "SW1" and "SW2". Notice how SW1 is wired. If the input Y is ON (1), pin B of SW1 is wired to the output, and the output of SW1 is connected to an OFF (0) signal. If the input Y is OFF (0), pin A is wired to the output, and the output is connected to an ON (1) signal. What this switch does is convert an ON (1) signal to an OFF (0) and an OFF (0) to an ON (1). This is actually a simple binary arithmetic operation in itself, known as "inversion", and SW1 is equivalent to an "inverter gate" in modern terms.

The input X controls the SW2 switch. If the input X is ON (1), SW2 is connected to the output of the SW1 inverter through pin B. If the input X is OFF (0), SW2 is directly connected to the input Y. The following table shows the XOR gate outputs for the values of the X and Y input pins:

: Y = ON (1) Y = OFF (0) : ---------- ----------- : X = ON (1) OFF (0) ON (1) : X = OFF (0) ON (1) OFF (0) : ---------- -----------

This can be seen with a quick inspection to define an XOR operation. By the way, an XOR gate can also be regarded as a "controlled inverter gate", in that if one input is 1, the second input is inverted, and if the first input is 0, the second input is passed through unchanged. Of course, to XOR binary values with multiple bits, we would build multiple XOR gates. To XOR five-bit Baudot codes, we would build five XOR gates, using a total of ten switches.

Please remember that this explanation is completely conceptual and ignores practical issues such as the type of electrical signals, switch construction, and so on, and isn't based on any actual specific implementation of an XOR for a real telecipher machine. However, this is one way it could have been done, how it was done in practice almost certainly followed a similar line of reasoning, and indeed a modern microelectronic XOR gate is conceptually similar as well.

* Gilbert Vernam's idea was to encipher plaintext Baudot codes by XORing them with a random stream of bits used as a mask. Suppose we have the following Baudot codes:

: data: 10100 00001 00110 10010 00100 10100 00110 10000 10010 00001 01010

-- and the following stream of bits chosen as a mask:

: mask: 01001 00101 11011 10110 00111 11001 10101 01010 10000 11001 10001

XORing these two streams gives:

: data: 10100 00001 00110 10010 00100 10100 00110 10000 10010 00001 01010 : mask: 01001 00101 11011 10110 00111 11001 10101 01010 10000 11001 10001 : ----------------------------------------------------------------- : cipher: 11101 00100 11101 00100 00011 01101 10011 11010 00010 11000 11011

The cipher bit stream is then transmitted by wire or radio. Deciphering is simple, as the XOR operation has a neat symmetry. All the receiver has to do is XOR it with the same mask to get the original Baudot codes:

: cipher: 11101 00100 11101 00100 00011 01101 10011 11010 00010 11000 11011 : mask: 01001 00101 11011 10110 00111 11001 10101 01010 10000 11001 10001 : ----------------------------------------------------------------- : data: 10100 00001 00110 10010 00100 10100 00110 10000 10010 00001 01010

Such a cipher is conceptually simple. The troublesome part, unsurprisingly, is making sure that the sequence of bits in the mask is as long and unpredictable as possible.

Vernam's original idea was to build a telecipher machine that could read two paper tapes. Paper tape was discussed in an earlier chapter as an element of the US M-134 code machine, and in the context of this chapter it can be seen more specifically as a primitive scheme for storing sequential digital data. A hole punched in the paper tape could represent, say, a "1", while the absence of a hole could represent a "0". The reverse might be true, the principle remains the same. The tape could then be wound through a "paper tape reader", which had opto-electronic detectors to sense punch holes. For example, for the plaintext stream given above:

: 10100 00001 00110 10010 00100 10100 00110 10000 10010 00001 01010

-- the paper tape might look like this, with an "o" representing a hole (defining a 1 bit) and a "+" representing a hole for the cogwheel gear used to feed the tape through the reader:

: ----------------------- : + + + + + + + + + + + : o o o o o : o : ... o o o o o ... : o o o o o : o o : + + + + + + + + + + + : -----------------------

In Vernam's concept, one paper tape would store the plaintext, while the other stored the mask. Interestingly, this work led to Joseph Mauborgne's discovery of the one-time pad. Vernam initially believed that he could use a short random key repeatedly, but this provided a periodicity that weakened the cipher. He then suggested multiplying two random keys together to generate a key that was a multiple of the two. Mauborgne showed that even a completely random key was not secure if it was used more than once, and so devised the one-time pad, or in this case the "one-time tape".

Both the virtues and the drawbacks of the one-time tape cipher were quickly obvious. Distributing unique, long, random keys was impractical, and so other means had to be devised to generate a long and unpredictable, or "pseudo-random", mask value from a simple group of initial settings.

* It was Parker Hitt who figured out how to generate such mask values. The basic element for doing this job was a "wheel" that stepped forward with every character processed by the telecipher machine, in much the same way that an Enigma rotor stepped forward with every character encrypted in a message.

The wheel could optionally have a "pin" at every step position along the edge of the wheel, with step positions having a pin or no pin in a random sequence. The pin pattern could be changed by the operator. The pins were used to control a mechanically-driven switch, wired as part of a switch circuit that would invert a bit, or not invert a bit, depending on whether a pin was present or not. This meant that as the wheel rotated with each character processed, the pattern of pins generated a matching pattern of "1"s and "0"s.

Of course, since Baudot codes have five bits, we need five of these elements in parallel, each with a wheel with a different pin pattern, to generate the pseudo-random mask values. The next issue is the length of the mask sequence, which should be very long. The brute-force way would be to make the wheels as large as possible, but even wheels with hundreds of positions wouldn't be long enough. Hitt came up with a better approach. Suppose we have one wheel with five positions that generates the following binary sequence:

: W1: 10010

-- and a second wheel with seven positions that generates another binary sequence:

: W2: 1100101

These are unrealistically small wheels, but they are convenient as examples. Now suppose the two wheels are rotating in parallel. Then the sequence defined by the two wheels won't repeat until after 5*7 = 35 rotations, when the two wheels are back in step again. The following example illustrates, with the bit sequences broken up in groups of five bits with spaces to make it easier to read:

: W1: 10010 10010 10010 10010 10010 10010 10010 10010 10010 ... : W2: 11001 01110 01011 10010 11100 10111 00101 11001 01110 ...

By extension, if there are five wheels in parallel, each with a different prime number of positions, then the sequence won't repeat until after a number of rotations equal to the product of all five of those prime numbers multiplied together. So if the number of positions on the five wheels were 5, 7, 13, 17, and 23, then the length of the sequence would be:

: 5*7*13*17*23 = 177,906

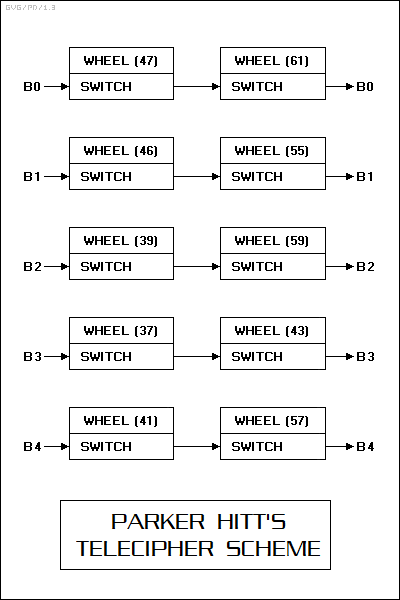

This is still much too short. Of course, wheels with larger primes, such as 43 or 51 could be used, but Hitt extended the concept to greatly multiply the length of the sequence, by using two wheels connected in series for each of the five Baudot bits. This scheme effectively XORed the two sequences together, and if they were different prime values, the length of the two sequences would be the multiple of the prime values.

Using the five-position and seven-position wheels described above but operating in series, not parallel, gives:

: 10010 10010 10010 10010 10010 10010 10010 10010 10010 ... : 11001 01110 01011 10010 11100 10111 00101 11001 01110 ... : ------------------------------------------------------ : 01011 11100 11001 00000 01110 00101 10111 01011 11100 ...

This meant that the length of the sequence was not only equal to the product of the number of positions on all ten wheels, but also lengthened the sequence for each of the five bits, making the sequence harder to predict.

Incidentally, the number of positions on the wheels doesn't actually have to be a prime number: the only important requirement is that they have as few common factors as possible. So, we could imagine a possible encryption scheme featuring ten wheels -- five pairs -- with values marked as below:

-- where "B0" to "B4" are Baudot input bits, and "X0" to "X4" are encrypted output bits. The size of the sequence generated by these wheels is given by:

: 47*61*46*55*39*59*37*43*41*57 = : : 47*61*(2*23)*(5*11)*(3*13)*59*37*43*41*57 = : : 6.21E16

This is on the same order as the number of possible configurations of the Enigma machine. Using such a telecipher system would be similar to using an Enigma machine, with the cipher key amounting to the initial positions of the wheels.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Germans adopted telecipher machines for high-level communications in World War II, the best-known of them being the Lorenz "Schlusselzusatz 40/42 (SZ-40/42)" machine. "Schlusselzusatz" meant "key attachment" and meant that the device was a box without a keyboard or printer that was used in conjunction with a conventional teletypewriter.

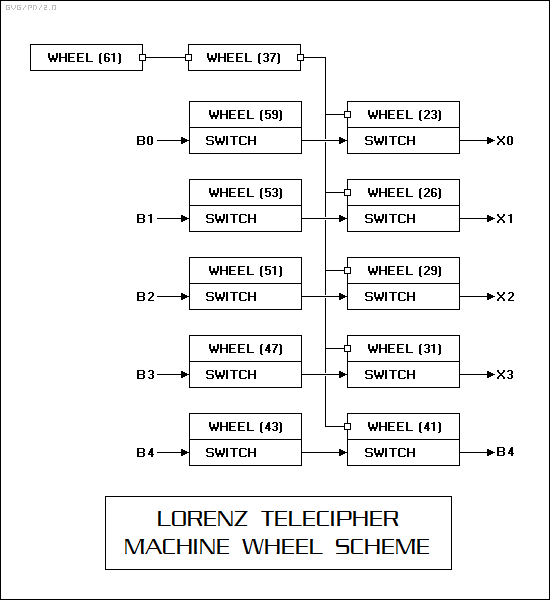

Although the example in the previous section defined a telecipher machine with ten wheels, the Lorenz telecipher machines actually included two extra wheels, for a total of twelve. The number of positions on each wheel was 23, 26, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, 47, 51, 53, 59, and 61:

The two extra wheels were not linked to switches. They were added was because Hitt's original scheme had proven to have some vulnerabilities that could be reduced if the wheels advanced in an irregular fashion. The set of five wheels on the right above, and the added wheel with 61 positions, advanced with every character. The 61-position wheel was mechanically coupled to the wheel with 37 positions; it would only advance if there was a pin active on the 61-position wheel. The 37-position wheel was mechanically coupled to the five second-stage wheel-switch units; they would only advance if there was a pin active on the 61-position wheel.

Lorenz was used by the German Army high command for high-level communications. The first Lorenz transmissions were picked up in early 1940 by the British police, who were hunting for possible German spy transmissions from Britain. One of Bletchley Park's top codebreakers, Brigadier John Tiltman, became interested in the these transmissions, and soon recognized that they were being produced by a Vernam-style telecipher machine. The series of messages were codenamed FISH, and the machine that generated them was codenamed TUNNY. As the volume of FISH intercepts grew, a new section of Bletchley Park was set up to focus on them. This section was under the command of Major Ralph Tester, and so was known as the "Testery".

The first step in cracking FISH was to determine the operation of TUNNY. Unlike Enigma, the British didn't have working versions of the TUNNY machine themselves, and they had to reverse-engineer TUNNY from the FISH intercepts. This exercise was based on one of the interesting properties of an XOR operation. If Holmes XORs two different Baudot characters with the same mask, say:

: 10010 11001 : 01110 01110 : ----- ----- : 11100 10111

-- then if he XORs the two results:

: 11100 : 10111 : ----- : 01011

-- the result is the same as the XOR of the two original Baudot characters:

: 10010 : 11001 : ----- : 01011

In other words, the mask has been eliminated. If Holmes knows what the two characters are, or in other words he has cribs into the ciphertext, he can then determine the mask sequence. However, the cribs can't be the same text, because an XOR of a value with itself always gives a zero result.

That might seem to be a very slender thread to grasp, but it is such slender threads that break ciphers. Occasionally, German operators used the same TUNNY wheel starting positions for two different messages, an event that the Bletchley Park codebreakers referred to as a "Depth", which gave hints as to the operation of TUNNY.

A few Depths were discovered, but did not reveal much about the TUNNY machine. However, on 30 August 1941, a German operator sent a message containing about 4,000 characters. On completion, the receiving operator replied that he hadn't received the message properly, and that it should be resent. The message was sent again, with the wheels set to the same starting position as before. This was a ghastly blunder, contrary to all proper procedures for using the Lorenz machine; any operator caught doing this could expect harsh punishment.

This error might not have been so deadly had the two messages been exactly the same, since XORing them together would have yielded a completely uninformative string of zeroes. Fortunately for the British, the sending operator didn't type the second message into the Lorenz machine in exactly the same way as the first. For example, the first message began with the phrase "SPRUCHNUMMER (message number)", as was standard practice, but with the second message the operator abbreviated it to "SPRUCHNR". In all, the second message was about 500 characters shorter than the first message. Tiltman was able to obtain the text of both messages, and more importantly to determine the mask sequence used to encipher them.

Tiltman passed the sequence on to Bill Tutte, who had recently come to Bletchley Park after graduating from Cambridge with a chemistry degree. Over a period of two months, Tutte and some of his colleagues in the Research section managed to use the sequence to reverse-engineer the TUNNY machine. In early 1942, the British Post Office Research Laboratories at Dollis Hill was asked to build a TUNNY machine, which was duly designed, constructed, and delivered. This machine deciphered FISH messages, but it could do so only as long as the initial wheel settings were known. Unfortunately, this took from four to six weeks, and by that time the intelligence was of very little value.

BACK_TO_TOP* A Cambridge mathematician named Max Newman was assigned to see how the deciphering process could be automated, with the assistance of two Bletchley Park cryptanalysts, Irving John Good and Donald Michie. The result was a machine built by Dollis Hill named "Heath Robinson", after a British cartoonist who liked to come up with screwball machines.

The Heath Robinson machine read two paper tapes, one punched with the ciphertext, the other with the mask sequence of the Lorenz machine. The machine could scan the ciphertext against the mask repeatedly, looking for a match. Heath Robinson went into operation in September 1943, but it proved a disappointment, mostly because it was very unreliable. A particular problem was that the paper tapes were fed in at very high speed, a thousand characters a second or more, and tended to snap.

Heath Robinson worked well enough to show that the basic concept was sound. It just needed a little work. Newman went to Dollis Hill and spoke with a brilliant electronics engineer named Tommy Flowers about the problem. Flowers suggested that an electronic system -- based on vacuum tubes or "valves" as they were known in Britain, instead of an electromechanical system -- could do the job.

Flowers' machine was more complicated than any piece of electronics built to that time, and there was great skepticism that such a "Colossus", as it was named, could be built and made to work. In particular, many believed that with large numbers of valves one would always be failing, and the Colossus would never be able to operate for more than a short period of time. Flowers replied that vacuum tube systems tended to be much more reliable if they were run continuously and not switched on or off. The project went ahead, with design work beginning in March 1943, and the first Colossus Mark I, with a total of 1,500 valves, in trials at Dollis Hill by December 1943.

The Colossus was shipped to Bletchley Park, reassembled over Christmas 1943, and was fully operational by January 1944. Lorenz began to provide valuable intelligence for Allied commanders preparing for the invasion of France that coming spring, most significantly indicating that the extensive deception effort, intended to fool the Germans that the invasion would be at the Pas de Calais instead of Normandy, was working as planned.

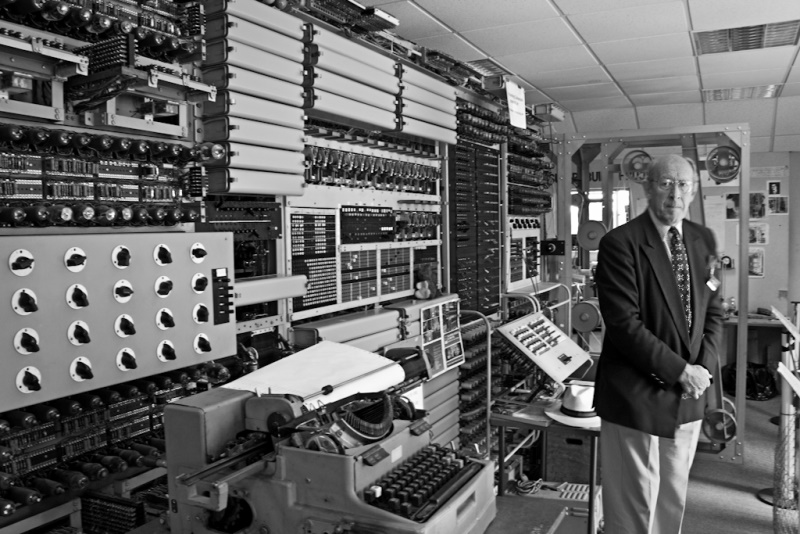

The initial Colossus Mark I was followed by the improved Colossus Mark II in June 1944. The Mark II had 2,400 valves and 800 relays. The system was surprisingly reliable, as Flowers had predicted. The Mark I was updated to Mark II specification, and eight more Mark IIs were built, for a total of ten "Colossi" in all. Each Colossus filled up a room, with multiple racks taller than the operators, plus a paper tape reader system for ciphertext input and a teletypewriter for output. Colossus read the ciphertext from paper tape at a rate of about 5,000 characters per second, with the mask sequence generated by an electronic system, not by paper tape as it had been with Heath Robinson. It was reprogrammable to a very limited extent, using patch cords and switches.

The original Mark I Colossus was only designed to determine the mask sequence position relative to the ciphertext, a task known as "wheel breaking", with the final decryption performed by another Bletchley Park section using less automated means. Decrypts normally took a few days. The Colossus operators also became adept at modifying the operation of the machine interactively to deal with difficult decryptions, with the technical "boffin" shouting changes at two WREN assistants and seeing what the results were.

After gaining experience with such techniques, Good and Michie figured out ways to use the machine to help in "pin breaking", or deciphering the pin patterns of Lorenz wheels, which the Germans changed periodically. The Colossus Mark II's additional circuitry was designed to provide further leverage for pin breaking, though much of the work still had to be done by manual means.

The Germans also used another telecipher machine for high-level communications, the Siemens & Halske "T-52" series, which the British codenamed STURGEON, in keeping with the FISH theme. STURGEON's operation was along the lines of that of TUNNY, but it was an entirely different device, being a complete telecipher system with keyboard and printer, and not just an accessory box. Details on the British effort against STURGEON are scarce. It appears that it was not cracked as well as TUNNY, possibly at least partly because it wasn't in as widespread use, and wasn't seen as worth the same level of effort.

* After the end of the war, eight of the ten Colossi at Bletchley Park were immediately dismantled. The two others were moved about and finally destroyed in 1960, when all the plans for the machine were destroyed. Why the plans were destroyed at such a late date is hard to understand, unless it was through tragic bureaucratic carelessness. The existence of Colossus was not revealed until the mid-1970s, when the whole ULTRA operation became public.

Colossus might have been lost forever had it not been for Anthony E. Sale, now in charge of the museum at Bletchley Park. In the early 1990s, he began to collect what few scraps of information that he could find on Colossus in hopes of rebuilding it. Sale used his own money to seed a rebuild project, as he knew that if he waited for official funding, many of the people who had worked on Colossus wouldn't be around any longer to help.

Tommy Flowers and other Colossus alumni provided useful technical assistance, Sale was able to find sponsors to provide funding, and in 1996 Flowers switched on the rebuilt Colossus. It may not have been exactly the same as the original in every minor detail, but it was close enough for all practical purposes, and an extraordinary accomplishment. Since 1996 was the 50th anniversary of the introduction of the American ENIAC, long regarded as the first computer, the British working on the project felt a strong competitive angle to the rebuild of Colossus to show the Americans who had really come first.

There really didn't seem to be much of a dispute, and in fact the effort had been greatly aided by American assistance of a sort. US reports on Bletchley Park work had been released into the US National Archives in 1995, and Sale found them by searching the archive catalog over the Internet. Furthermore, it was already generally acknowledged by the mid-1990s that Colossus had preceded ENIAC, and certainly nobody had ever contested Turing's pioneering work in the computing field.

There was also the irony that both Colossus and ENIAC had been beaten to the punch by the ABC computer built between 1939 and 1942 by Professor Victor Atanasoff of Iowa State College in the US, with a US patent court formally ruling in the mid-1970s on the patent priority of Atanasoff's machine over ENIAC. Furthermore, the ABC, Colossus, and ENIAC were still not modern computers since they were not reprogrammable in any serious way, being "hardwired" to tackle a specific class of problems.

The first "reprogrammable" computer was British, and nobody disputes it. The "Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator (EDSAC)" was built in 1949 by Maurice Wilkes of Cambridge University in the UK -- though to muddy the trail further, he got most of his inspiration from attending lectures by John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert, the American fathers of ENIAC. Elaborate technologies tend to have elaborate parentage; further discussion of the whole legalistic priority dispute quickly becomes tiresome, as if it wasn't already.

BACK_TO_TOP