* General Grant had not been able to capture Vicksburg through brute force, so he settled in for a siege. Lacking supplies and with no relief in sight, General Pemberton finally surrendered on 4 July 1863. Less than a week later, Port Hudson downriver surrendered to Nathaniel Banks; the Union now controlled the Mississippi River. Confederate forces in the state of Mississippi were then driven off, and resistance crushed. Grant was again a Union hero.

* Having found frontal attacks suicidal, Grant was content to resort to a traditional siege. His army was receiving regular food and supplies, Pemberton's was not, and what food there was in Vicksburg had to be shared with civilians. Grant's artillery fired into the city around the clock, assisted by bombardments and target spotting from Porter's gunboats.

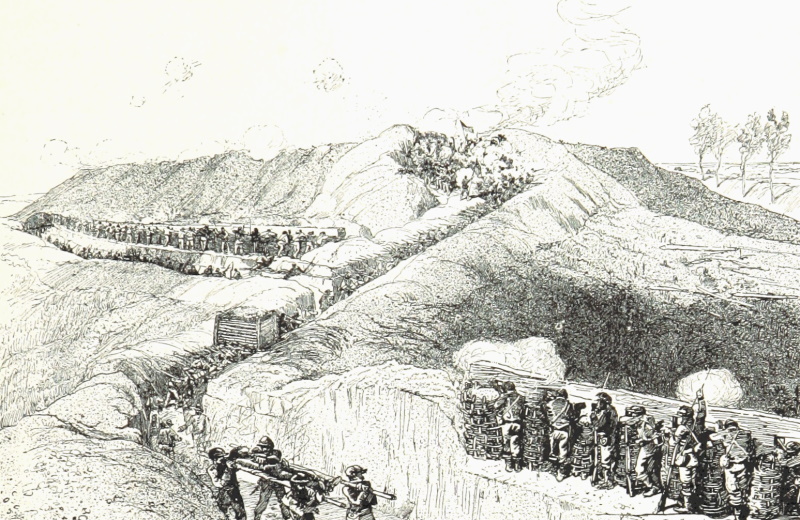

Grant had few trained engineers, but with a combination of a little reading and a lot of sense and ingenuity, his soldiers quickly learned the art of the siege. They dug zigzag trenches, or "saps", towards Confederate lines, protected by cylindrical baskets woven from twigs and filled with dirt, known as "sap rollers", that could be rolled forward to provide protection for diggers. Trench mortars were improvised by shrinking iron bands around tree trunks, then hollowing them out to accommodate 6- or 12-pound (2.7- or 5.4-kilogram) shells.

The defenders rolled fuzed barrels full of powder, which they called "thunder barrels", down into the Yankee positions, and recovered dud Union shells to put them to use in a similar fashion. Confederate sharpshooters sniped at the Union soldiers, while rebel gunners occasionally fired turpentine-soaked projectiles into sap rollers, setting them on fire. The Federals dug lateral slit trenches from the main trenches, from which Union sharpshooters sniped back at the Confederates -- doing a good job of making the Confederates keep their heads down. The Federals also accumulated artillery to the extent that any time the rebels tried to use a cannon, it would quickly be blasted away by counterfire.

The Federals pressed forward, knowing the outcome was not in doubt. They amused themselves by sticking a cap on a ramrod, shoving it above the trenches, and seeing how many bullet holes it would accumulate. With the lines drawing so close, soldiers from the two sides began to shout jokes and taunts at each other, and fraternize to an extent. In one case, a Union soldier whose brother was in the Confederate army actually went into the town, the two spending time wandering around together.

The Federals kept tightening their grip. By mid-June, Grant had over 200 guns firing into the city, while Porter added the weight of his fleet's armament to the bombardment. His mortar boats threw tens of thousands of shells into Vicksburg. The targets were Confederate defenses, but since these were all over the city, the effect was that no place was safe. All the buildings were destroyed or damaged. Civilians began to dig caves into Vicksburg's yellow clay hills, prompting Union soldiers to call the place "Prairie Dog Village". Some of the caves were mere cubbyholes, while others were large and well-furnished. Only about a dozen civilians were reported killed during the siege, with possibly three times more wounded, but the citizens of Vicksburg still lived in continuous terror.

On the other side of the lines, Grant had his own fear: that Joe Johnston would attack, and allow Pemberton's army to break out. Johnston was rumored to have 30,000 men, and though Grant had a low opinion overall of Confederate generals, he respected Johnston. Grant had his men build a second set of defenses faced to the rear to deal with any attack by Johnston, and assigned divisions to keep an eye on him.

Given that Grant's well-supplied army outnumbered both Pemberton's and Johnston's forces combined, and that communications with Pemberton were almost completely cut off, Johnston had little chance of seriously threatening the entrenched Federals, and he knew it. He wired Richmond:

I CONSIDER SAVING VICKSBURG HOPELESS.

Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon energetically prodded Johnston to attack Grant, even if only as a matter of honor. Johnston did not see the honor in the futile wastage of his men, who he thought of as his own sons. Southern newspapers bitterly criticized him, one stating that he was giving Grant a "terrible letting alone"; but Johnston, rarely inclined to daring, did nothing.

* Life was slow for Grant at that time, but he at least had the satisfaction of solving a problem that had been bothering him for a long time. General John McClernand's lack of military competence and consideration for others, coupled with his continuous posturing for the newspapers, had not endeared him to Grant or any of the other generals in Grant's command. Grant had been waiting for a good excuse to have him removed.

Some time earlier, Grant had sent his young inspector general, Lieutenant Colonel James H. Wilson, over to McClernand to deliver an order, requesting that McClernand provide troops to a force commanded by Sherman that was keeping an eye on Joe Johnston. McClernand exploded in Wilson's face, shouting: "I'll be goddamned if I'll do it!" -- and followed with a stream of abuse. Wilson responded with a cold fury, threatening to "beat the boots" off of him. McClernand backed up and apologized, but when Wilson told Grant of the incident, Grant replied: "I'll get rid of McClernand the first chance I get!"

In mid-June, Sherman was given a newspaper that quoted McClernand as saying the positive achievements of the bloody fiasco in front of Vicksburg on 22 May had been due to his leadership, and the defeat was due to the failure of Sherman and McPherson to back him up. Sherman and McPherson were of course enraged. The accusations would have been vicious and unjust even if McClernand had expressed them in private, but he had expressed them in public. That was going much too far: on 18 June, Grant wrote up an order relieving McClernand of his duties.

Lieutenant Colonel Wilson took the order to McClernand's tent late that night, and found McClernand waiting for him, wearing a full dress uniform; clearly, the visit was not a surprise. McClernand read the order and said: "Well, sir! I am relieved!" Wilson did not hide his satisfaction, but McClernand uncharacteristically managed to demonstrate a little grace under pressure, saying: "By God, sir! We are both relieved!" McClernand protested to the President himself, but Lincoln politely declined to help him. McClernand was out of Federal Army of the Tennessee for good.

With McClernand gone, Grant focused on taking Vicksburg. By this time, Grant's strategy of digging his way in had taken a more devious turn. On 23 June, 35 soldiers who had been coal miners were put to work digging a tunnel under the rebel lines. In two days, they had dug a tunnel 45 feet (13.7 meters) long, which then branched off to three smaller tunnels 15 feet (4.6 meters) long. On 25 June, these tunnels were loaded with 2,200 pounds (1 tonne) of gunpowder.

The Confederates had become aware of the mine and were in fact digging a countermine to try to stop the Yankees -- even as the gunpowder was being put into place. That afternoon, Grant's men set off the charge, killing six Confederates and blasting a crater in the rebel defenses. A black cook named Abraham who had been helping the rebel soldiers was tossed into Union lines with no serious injury; he was adopted by the Yankee soldiers, becoming something of a sideshow attraction.

A Federal brigade under Brigadier General Mortimer D. Leggett charged into the crater, but was stopped cold. The Union diggers had lost the element of surprise and the rebels were waiting, greeting the Yankees with terrible volleys of rifle fire. The attack bogged down into bloody close-quarters combat, with the Federals tossing black-powder grenades while the Confederates caught them and tossed them back. The rebels also rolled lit shells into the crater. The Federals hung on to their position in the crater for three days, to finally pull back on the afternoon of 28 June. They had lost almost 200 men, while the Confederates had lost less than half that number.

The Federals set off another mine on 1 July, not too far from the position of the first. This second mine caused severe damage, killing 12 rebels and injuring 108. However, Federal officers did not believe that the explosion had seriously disrupted Confederate defenses, and so did not attempt to follow it up with an assault.

BACK_TO_TOP* Downriver at Port Hudson, Nathaniel Banks was conducting his own siege, while simultaneously fending off Halleck's meddling. Like Grant, Banks did not welcome Halleck's interference in his plans, and had kept him in the dark. Halleck had of course discovered that Banks had not joined forces with Grant, Banks preferring instead to focus on Port Hudson. Halleck wrote Banks critical messages dated 3 and 4 June, expressing dissatisfaction and strongly suggesting that Banks send "spare forces" to Vicksburg. Banks replied with strained patience his reasons for moving on Port Hudson, and Halleck grudgingly came around -- Halleck was annoying, but not completely unreasonable. By that time, relief from badgering by Halleck was likely very welcome to Banks, since things had not otherwise been going well.

Reports from Confederate deserters in early June had indicated that the defenders of Port Hudson were not far from running out of food and that their morale was poor. However, when Banks' men made a probing night attack in the dark hours of 11 June, they were firmly driven off by the alert defenders. Although this bloodying gave Banks pause, new reports from Confederate deserters indicated the defenders of Port Hudson were on their last legs. On 13 June, Banks conducted an hour-long bombardment of the rebel defenses, and then sent a formal note across the lines demanding that Gardner surrender. Gardner returned a shorter, but equally formal, refusal.

The next day, Banks pounded Port Hudson for an hour once again, and sent his men in. The results were disastrous: the Federals suffered 1,792 casualties, the Confederates only 47. The only thing that Banks learned from the fiasco was that Confederate deserters were not to be trusted. He did not know if Gardner's men were really at their limits, but he was becoming only too aware that his own men were. Fighting in Louisiana swamp and scrub in June was unhealthy, and many of Banks' men were falling ill and dying. By this time, he was down to 14,000 effectives. Many of his men were close to the end of their enlistments and had no enthusiasm for further soldiering.

In response to Banks' reports of the wavering of his soldiers, Halleck gave helpful, and unfortunately characteristic, advice: "When a column of attack is formed of doubtful troops, the proper mode of curing their defection is to place artillery in their rear, loaded with grape and canister, in the hands of reliable men, with orders to fire at the first opportunity."

Banks, for whatever his other limitations, was no monster, and was unlikely to have found Halleck's recommendation inspiring. Banks also had other sources of discouragement. Frantic reports indicated that Confederate forces were massing to move on New Orleans in his rear. Although such news could not have helped him sleep well at nights, he was determined to maintain his hold on Port Hudson. The rebels might retake New Orleans before Port Hudson fell, but if so, Banks would simply have to take it back again when he was free to do so.

In the meantime, the Federals kept blasting Port Hudson with artillery fire. If the rebels were too well dug in to be done much real harm, they could at least be given no rest. The number of Confederate deserters increased through the month, and if Banks no longer took much faith in what they said, the quantity said something in itself.

BACK_TO_TOP* By the first of July, all evidence showed Grant that Vicksburg couldn't hold out much longer. Artillery bombardment and sharpshooter fire were picking off the defenders, while those that remained were slowly starving.

Pemberton had tried to coordinate food distribution, but once reserves of livestock were gone there wasn't much left for soldiers and citizens to eat. They turned to horses and mules, then dogs and cats, and gathered blackberries and weeds to eat. They made a wretched bread of ground peas. Even water was in short supply, since the Mississippi was too dirty to drink, and there were few wells in Vicksburg. Pemberton's men were emaciated, weak, and covered with parasites. They could not hold out indefinitely.

Grant was aware of all of this. He planned a final assault for 6 July. Johnston, in the meanwhile, had finally decided that he had to attack Grant's positions to help Pemberton's army escape, scheduling his attack for 7 July. That wasn't soon enough to help Pemberton, who knew the defense of the city was on its last legs. On 1 July, he consulted his division commanders to learn the condition of their troops. The response was that the men were too exhausted to even break out the city.

On 3 July, Pemberton sent Major General John Bowen over to the Union lines under a flag of truce to discuss surrender. Bowen was dying of dysentery, but he had been friends with Grant before the war, and hopefully that might count for something in the negotiations. Grant told Bowen that the only thing he wanted was "unconditional surrender", but agreed to further discussions. That afternoon, Pemberton and several of his officers came across the lines to meet with Grant and a handful of his generals.

Grant told Pemberton that he had to surrender unconditionally. Pemberton was not the kind of person who was easily cowed, and the meeting did not go well. After the Confederates had returned to their lines that evening, Grant sent over final terms that were surprisingly lenient, in particular indicating that all of Pemberton's men would be paroled. That was done for practical reasons. Grant did not want to deal with 30,000 prisoners when he could better use his resources to keep up the pressure on the Confederacy. Furthermore, it was unlikely many of the rebels were in any physical condition to do much fighting for the Confederacy any time soon, and most were too discouraged to want any more of the war.

Sometime after midnight, Pemberton sent a message to Grant. Grant, sitting in his tent with his son Fred, read the note, then said to the boy: "Vicksburg has surrendered." It was the 4th of July, 1863.

The Federals quickly moved into the city. There was little gloating; Union soldiers brought sacks of food to help the famished Confederates. One Federal outfit raised a cheer for "the gallant defenders of Vicksburg." There was a degree of fraternization between the soldiers of the two sides as well, and even some edged joking. One Confederate called out to a Union engineering officer, a Major Lockett, who had been on the move a great deal while working on Federal siegeworks: "See here, mister, you man on the little white horse! Danged if you ain't the hardest feller to hit I ever saw. I've shot at you more'n a hundred times!" Lockett took it in good humor.

Porter sent a fast steamer up the Mississippi to Cairo, the nearest place where news could be wired to Washington, and on 7 July Navy Secretary Welles dashed into Lincoln's office with a telegram signed by Porter:

I HAVE THE HONOR TO INFORM YOU THAT VICKSBURG HAS SURRENDERED TO THE US FORCES ON THIS 4TH DAY OF JULY.

The Battle of Gettysburg, in Pennsylvania, had ended the day before, but the defeated Confederates had escaped, much to the exasperation of the President. He was then elated by the news of the fall of Vicksburg. The President put an arm around Gideon Welles' shoulders and say: "What can we do for the Secretary of the Navy for this glorious intelligence? He is always giving us good news. I cannot in words tell you my joy over this result. It is great, Mr. Welles, it is great!"

Lincoln wasn't alone in his joy. There was celebration throughout the North. Churches rang bells and cities fired off cannon salutes. Along with the defeat of the Confederates at Gettysburg, there was depression in the South. The perceptive among Confederate leadership realized that their hopes of winning the conflict had just greatly faded. In hindsight, in fact, the Confederacy had just all but lost the war.

* There remained the problem of Port Hudson -- but not for long. Banks' men had dug their way close to Confederate lines; they planned to blast craters in them on 11 July to allow a storming party of a thousand men to pass through. Fortunately for them, on 7 July the news arrived that Vicksburg had fallen.

There were loud celebrations in the Yankee positions. When the Confederates on the other side of the lines were told the news by their opponents, many refused to believe it, calling it "another damned Yankee lie". The next morning, Major General Gardner took the sensible approach of requesting under a flag of truce evidence from Banks that Vicksburg had in fact fallen. Gardner was provided with convincing evidence, and surrendered Port Hudson on 9 July 1863.

After the fall of Port Hudson, Banks paroled all the enlisted Confederate prisoners, though he held on to the officers. Banks had reason to feel magnanimous and sent a wagon train loaded with rations to the starved defenders. He also graciously returned Gardner's sword to the rebel general at the end of the formal surrender ceremony "in recognition of the heroic defense".

Banks had let most of the Port Hudson garrison go because he wanted to be free to deal with Confederate forces that were then threatening New Orleans. Once Banks returned his troops to New Orleans, the Confederates pulled back; they remained a threat, but not an active one for the moment. Banks was in high spirits for his success at Port Hudson: He wrote his wife: "We have taken from them the power to establish an independent government. It can never be done between the Mississippi and the Atlantic. You can tell your friends that the Confederacy is an impossibility."

BACK_TO_TOP* Although Vicksburg had fallen, Grant still had Joe Johnston to worry about. Catching and destroying Johnston and his army was unlikely, but at least they could be driven off the playing board for the time being.

Johnston's men had reestablished themselves on the Yazoo, and so Grant ordered 5,000 men to steam upriver under the protection of three of Porter's gunboats. Grant sent orders to Sherman as well: "I want Johnston broken up as effectually as possible, and roads destroyed." Grant suggested that MacPherson's corps be split off to assist Banks in front of Port Hudson, but that proved unnecessary with the surrender of the fortress downriver.

The Yazoo river expedition set out on the morning of 12 July. On the 13th, the force encountered fire at Yazoo City, from guns manned by rebels under the enterprising Isaac Newton Brown. The Federals landed troops and forced the Confederates to withdraw, but when the Eads ironclad gunboat BARON DE KALB, previously SAINT LOUIS, steamed back upstream that evening, it hit two torpedoes and sank. None of the crew was seriously hurt, and though Porter was unhappy about the loss of the ironclad, it was acceptable for what had been gained. The expedition had succeeded in driving out Confederate forces, and smashing what few resources they had were able to assemble.

Sherman had been on the move for a week by this time. He had been forced to spend time rebuilding bridges, but on 6 July he set out in pursuit of Joe Johnston. Johnston, on learning that his attempt to relieve Vicksburg had become pointless with the city's surrender, had retreated back to Jackson to set about improving its defenses. The countryside was dry and dusty; Johnston hoped thirst would force Sherman into a rash attack that would be driven off with great loss.

Johnston greatly underestimated the stamina of Sherman's men, who drank from the few ponds where water remained, even though the Confederates had thrown carcasses of livestock in them to pollute them. Then torrential rains fell. It turned the roads into quagmires, but the Federals now had plenty of drinking water, and they weren't going to be stopped by some mud.

Sherman's men converged on Jackson on 10 July. While Johnston was not one to risk all on the offensive, there was no one keener on the defense, and Sherman knew better than to attack head-on. Instead, he worked around Jackson in an attempt to invest it, sending out parties to destroy the city's connections with the rest of the Confederacy. On 12 July, however, one of his divisions accidentally stumbled into a crossfire, with the lead brigade cut to pieces, losing 465 men; the division commander was sacked. Sherman's assessment of Johnston was confirmed. Sherman wrote Grant a few days later: "If he moves across the Pearl River and makes good speed, I will let him go."

In fact, Johnston realized he was close to being surrounded; he decided to withdraw on 16 July. That night he and his men pulled out of Jackson quietly and efficiently, taking with them everything they could carry of military value. During the fighting for Jackson, they had managed to inflict 1,122 casualties on the Federals at a loss of 604 to themselves. Sherman was as good as his word, and let Johnston go. The Federals then moved into the town, to completely demolish it. When they left the place, they nicknamed it "Chimneyville".

Sherman was an unusually complicated man, part amusing and part frightening, often sensible, but sometimes a bit mad. Although he found satisfaction in the misery his troops had inflicted on the rebellious population, he was careful to provide the locals with food and other supplies to allow them to survive over the short term. Even in this, he still found some satisfaction, gloating: "The inhabitants are subjugated. They cry aloud for mercy."

* Grant was not quite finished inflicting pain on Mississippi. On hearing reports that the rebels were busily running goods through Natchez, downriver from Vicksburg, Grant sent a brigade from MacPherson's corps under Brigadier General T.E.G. Ransom to investigate. Ransom arrived there in mid-month and found the hunting good, collecting a vast haul of ammunition and thousands of head of Texas cattle; he didn't lose a man on the raid.

A month later, Grant dispatched two cavalry columns towards Grenada, a rail junction on the Yabolusha River, a tributary of the Yazoo. Much of the Mississippi Central Railroad's rolling stock was stockpiled there, trapped by the destruction of railroad bridges in Jackson. One cavalry column moved south from Memphis, while the other was sent north by Sherman; they converged on the town on 17 August. The outnumbered garrison fought briefly and then fled. The raiders had a party destroying dozens of locomotives, hundreds of railroad cars, as well as the railyard itself. They were a little embarrassed to learn later that the rebels managed to salvage the valuable locomotive drive wheels; sledgehammers would become a common item of equipment on future raids.

BACK_TO_TOP* On 13 July, President Lincoln penned a congratulatory letter to General Grant, admitting that he, Lincoln, had doubts of the wisdom of Grant's strategy, but events had proven "you were right and I was wrong." Nathaniel Banks also received personal praise from the President.

On 16 July, the Union cargo steamer IMPERIAL arrived in New Orleans, having traveled the full length of the Mississippi undisturbed. Soon after, Lincoln summed up the victory in a melodious phrase: "The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea." Grant had already received his reward, with his rank as major general made permanent in the Regular Army, the assignment being retroactively effective to 4 July. Sherman and MacPherson were also promoted to the permanent rank of brigadier general.

Not everyone in the Union was entirely pleased by Grant's performance at Vicksburg. One noisy Congressional faction was greatly disturbed by Grant's willingness to let Pemberton and his soldiers go free on parole, predicting that these men would soon be back in the lines and would have to be beaten all over again. They sent a delegation to Lincoln to demand that Grant be sacked. Later, Lincoln told a friend: "I thought the best way to get rid of them was to tell the story of Sykes' yellow dog. Have you ever heard about Sykes' yellow dog?"

Sykes, as the President explained, was a childhood acquaintance who had a yellow dog he was very fond of, but the other children hated. They finally decided to deal with the dog by wrapping a piece of meat around a blasting cap. They whistled for the dog, and when he came to chew on the meat, they lit the fuze. The dog was blown to bits, and when Sykes came out to investigate, he picked up the tail and the pieces connected to it, saying: "Well, I guess he'll never be much account again, as a dog." Lincoln, having reached the punchline, added the moral: "I guess Pemberton's forces will never be much account again as a army."

Most of the delegation wasn't there to hear it. As Lincoln told his friend: "The delegation began looking around for their hats before I had got quite to the end of the story, and I was never bothered any more about superseding the commander of the Army of the Tennessee."

* Grant's belief that the defenders of Vicksburg had all they wanted of war was borne out by events. As Pemberton led his parolees across country to Demopolis, Alabama, they faded out of the ranks with every mile.

Pemberton had been instructed to report to Joe Johnston. One moonlit evening Pemberton approached Johnston's camp. Johnston had been good friends with Pemberton, and in fact at one point had wanted him to be his adjutant. Johnston got up and put out his hand: "Well, Jack old boy, I'm certainly glad to see you!" Pemberton simply went to attention, saluted, and said: "General Johnston, according to the terms of parole prescribed by General Grant, I was directed to report to you."

There was an awkward silence. Johnston lowered his hand. Pemberton saluted again, then turned his back on Johnston and walked away. They never saw each other again.

Pemberton had no credibility in the Confederacy. In mid-July, Jefferson Davis detached Hardee from Bragg's command and sent him to Demopolis to take control of what was left of Vicksburg's army. That left Pemberton without a command; no one wanted to give him another one. Jefferson Davis was sympathetic. He believed that Pemberton had done the best he could under difficult circumstances, and Davis always stood by his friends when all others abused them. In fact, Jefferson Davis felt that it was Joe Johnston's lack of aggressiveness that had doomed Vicksburg, not any failing of Pemberton's. Relations between Davis and Johnston, never good, had taken a turn for the worse.

Pemberton went to Richmond, where he would spend the better part of a year looking for an assignment. He finally could bear it no more, submitting his resignation as a lieutenant general to become a lieutenant colonel of artillery. Such was Pemberton's dedication to his adopted nation, or possibly his refusal to accept humiliation, that he went back into combat when no one wanted him to -- at a time when the cause had been clearly lost.

* Although General Grant was a national hero for his victory at Vicksburg, he received mixed rewards for it. He proposed to Halleck to join forces with Banks and move on Mobile, Alabama -- but the War Department had other ideas, rejecting the proposal in mid-August, to then begin to methodically loot Grant's command to provide help to other theaters. Various corps and divisions were sent south to New Orleans to reinforce Banks for offensive operations towards Texas; west for a drive into Arkansas; upstream to reinforce Memphis and Missouri; and east to help Federal movements into eastern Kentucky. Grant was reduced from five corps to two, the corps of Sherman and MacPherson, and some of their units were detached as well.

That left Grant with little to do. He didn't like the inactivity, but his political stock was good for the present and not a worry. He was now one of the only two permanent major generals in the army, the other being Halleck. Halleck was still his obnoxious superior, but the scales were at least better balanced in Grant's favor -- all the more so because the President had a realistic grasp of the strengths and weaknesses of both men.

With relatively little concern about watching his back and time on his hands, Grant went on what might later be called a "boondoggle", steaming upstream to Memphis, where he was the guest of honor at a banquet and wildly applauded. It was not something he was used to; he found he liked it. He then steamed downstream to Natchez, Mississippi, where he met with local Southern men of influence and found them pleasantly cooperative with the new powers in the land. He continued his trip down to New Orleans, arriving on 2 September, where he was given an opulent welcome by General Nathaniel Banks.

However, on 4 September, a horse he was riding through the city bolted at the sound of a locomotive; the horse ran into a carriage, falling to the pavement, and taking Grant with it. Grant had a remarkable knack with horses, but for once it seriously failed him. Grant was knocked unconscious and suffered a dislocated hip. He was so badly battered that he lay in bed for a week before the swelling and bruises subsided enough to even allow him to roll over.

Malicious rumors went around that Grant had been so drunk that he had simply fallen off his horse. Many tales linger of Grant's fondness for the bottle, not all of them very credible -- Grant could ride horses when he was blind drunk that most people wouldn't try to ride when they were sober -- but even Nathaniel Banks, who wasn't inclined to snipe at others, wrote his wife that Grant's drunkenness "was too manifest to all who saw him."

BACK_TO_TOP* This document was derived from a history of the American Civil War that was originally released online in 2003, and updated to 2019. It was a very large document, and I first tried to simply break it into volumes for publication in ebook format; however, that proved unsatisfactory, and I decided to rewrite components of it to tell the story of famous battles and such. This stand-alone document was initially released in 2022.

* Sources:

* Illustrations credits:

Maps are the work of the author. Finally, I need to thank readers for their interest in my work, and welcome any useful feedback.

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 apr 22 v1.0.1 / 01 mar 24 / Review & polish.BACK_TO_TOP