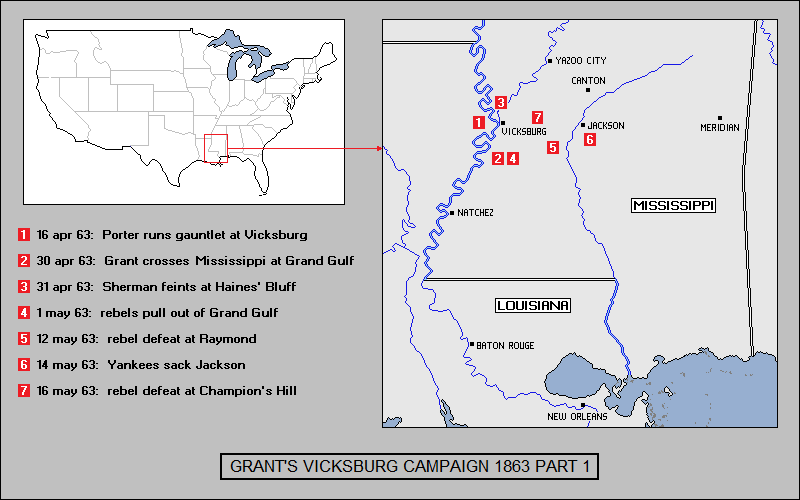

* Grant's run down the Mississippi past Vicksburg caught Confederate General John Pemberton, in charge of the defense of the city, flat-footed. Pemberton never regained his footing, either, with Grant moving fast and inflicting a series of defeats on the Confederates. However, Grant's frontal assaults on Vicksburg itself proved failures; downstream, Union General Nathaniel Banks was enduring similar troubles in his efforts to take the Confederate stronghold at Port Hudson.

* Grant's end-run around Vicksburg put him right where he wanted to be. He selected a place named Grand Gulf, on the east bank of the river 20 miles (32 kilometers) downstream from New Carthage, as the beachhead for his river crossing, and prepared his men for the move. In the meantime, Pemberton, who had reacted quickly to all of Grant's other experiments, was now bewildered.

On 11 April, Pemberton had reported to Richmond that Grant appeared to have given up and gone back to Memphis. Pemberton had been considering the transfer of forces to central Tennessee to reinforce Braxton Bragg, on the assumption that Grant was shifting troops to help Rosecrans. Porter's run past Vicksburg on the 16 April didn't fit Pemberton's preconceptions, and he couldn't make any sense of it.

The outnumbered Grant was taking every measure to make sure Pemberton stayed bamboozled. Grant's futile probes through the Yazoo Delta had at least one positive result: Pemberton had been forced to disperse troops through the region to defend against Yankee incursions, and early in the month, Grant had dispatched a division under General Fred Steele to Greenville, 100 miles (160 kilometers) north of Vicksburg on the east bank, to thrash about for a week and keep the rebels in an uproar. Steele's effort was successful, but was overshadowed by a second diversionary effort, one that would prove to be among the most spectacular adventures of Union cavalry in the war.

Federal cavalry had never got much respect; they had certainly never performed the spectacular raids that had so distinguished rebel cavalry commanders like Bedford Forrest. To be sure, the Union troopers were narrowing the gap, but they had never pulled off one of the daring excursions through enemy territory that had made Confederate cavalry a source of pride to the South.

It was time to give the rebels a taste of their own medicine, and the cavalry troopers of Grant's army thought they could do it. Unlike their counterparts back East, Western troopers often had extensive experience as horsemen from growing up on the frontier, and were a match in such skills for the best the Confederate cavalry had to offer. On the morning of 17 April 1863, 1,700 cavalrymen of the 2nd Iowa, 6th Illinois, and 7th Illinois, plus a six-gun battery of 2-pounder artillery left La Grange, Tennessee, just above the Mississippi border, and moved south across the state line, carrying five day's rations. Their mission and objectives were a mystery to all but their commanding officer and his lieutenants.

The commander was 36-year-old Colonel Benjamin H. Grierson, whose background would not have suggested any comparison with Forrest. Only a year and a half previously, Grierson had been a musician squeaking out a living as a music teacher in Illinois. He had protested loudly to General Halleck when he was assigned to the 6th Illinois Cavalry in 1861, since Grierson hated horses; he'd been kicked in the face by a pony when he was 8 years old, and scarred for life. However, Grierson seemed to have a natural aptitude for cavalry warfare, and Sherman had recommended him in the highest terms to Grant.

Two railroads ran north-south through Mississippi: the Mobile & Ohio, which skirted the Alabama border, and the Mississippi Central, which ran roughly down the middle of the state. They were crossed by the Southern Mississippi Railroad line, which ran east to west, forming a dividing line between the lower third and upper two-thirds of the state. Grierson was to cut these rail lines, tear down telegraph wires and poles, destroy rebel supplies, confuse the enemy, and generally raise hell in the enemy's rear.

Grierson's raiders quickly encountered small detachments of Confederate troops, getting into petty clashes. Word got back to the local Confederate cavalry commander, 29-year-old Clark R. Barteau, left in command after Van Dorn was sent off to assist Braxton Bragg in February. Barteau immediately set out after Grierson's troopers. Barteau only had 500 men, but Grierson had no reason to stand and fight; his mission was to cause damage and create confusion, and a clash would slow the Union men down behind enemy lines, only drawing more trouble on to them. On 20 April, Grierson weeded out about 150 of his men who had been injured or become ill and sent them back to La Grange, with orders to cover the tracks of the main force as best they could, and lure the Confederates along with them. The "Quinine Brigade" managed to confuse Barteau for the better part of a day.

Grierson wasn't done with the trickery, either. On the next day, 21 April, he ordered the 2nd Iowa Cavalry, under Colonel Edward Hatch, to split off and make a wide loop towards the rebel base at Columbus, Mississippi, then back to La Grange. Barteau took up the trail behind Hatch and caught up with him near the town of Palo Alto. A skirmish followed. Hatch outnumbered Barteau by 200 men, but decided to retreat; the longer he kept the rebels tied up chasing him, the less trouble they would make for Grierson. Hatch circled back north, drawing Barteau's cavalry into fights and leading them further and further away from Grierson's column. Hatch and his men would return to La Grange on the morning of 26 April, having successfully managed to draw rebel forces away, while Grierson continued south, leaving destruction in his path.

* Grierson's column was preceded by a group of scouts who were dressed as Confederate soldiers, which meant they would have been hanged if captured. The "Butternut Guerrillas" -- as they were known from their tan-colored Confederate uniforms -- scouted out towns ahead of the advance, seized bridges before they could be burned, captured telegraph offices to ensure that no warnings were sent, and located food and forage.

On 22 April, Grierson detached another unit for independent operations. The 35 men of Company B of the 7th Illinois Cavalry under Captain Henry C. Forbes were sent east to the town of Macon, Mississippi, to cut telegraph lines and sow confusion. On 24 April, Grierson's brigade reached the town of Newton Station, on the Southern Mississippi Railroad. Low on supplies by this time, the raiders were happy to capture two trains full of supplies and munitions. They celebrated for a short time, but Grierson ordered them to get to work, trashing the rail junction and burning whatever they couldn't carry off. Pemberton was in Jackson, Mississippi, at that time; he was so fixated on catching Grierson and his men that he had effectively forgotten that Grant was downstream from Vicksburg, and up to no good. Pemberton ordered tens of thousands of men into the field to trap the raiders.

Meanwhile, Captain Forbes and Company B were busy on their own. They entered Newton Station 15 hours behind Grierson -- but fell for one of Grierson's deceptions themselves, riding east when in fact Grierson had ridden west. Forbes ended riding into the town of Enterprise, southeast of Newton Station, the next day. He had been told there were no Confederates there, but found it full of enemy soldiers. Forbes coolly pulled out a white handkerchief, rode up to Confederate headquarters, and demanded in Grierson's name that they surrender. The rebels, confused, asked for an hour to consider it. Forbes agreed, and casually rode out of town with his company, shifting to a gallop when they got out of sight. He later wrote: "We never knew officially what the Confederates' reply was, as for reasons best known to themselves they failed to make it reach us. Perhaps it was lack of speed." Company B stopped to eat, but continued their retreat all through the night.

In the meantime, Pemberton had been told that Grierson was east of Newton Station, further confusing him. At that time, after a half day of rest at a plantation, Grierson was in fact moving west in hopes of linking up with Grant at Grand Gulf. He began torching bridges to slow down Confederate pursuit. Captain Forbes and Company B, who were now on Grierson's trail, were in grave danger of being trapped. On 26 April, he sent three men, including his brother Sergeant Stephen Forbes, to ride ahead on fresh horses, and try to make contact with the main column.

They rode hard; night fell, and they continued their ride, until they were challenged out of the darkness by a voice with a Northern accent: "Halt! Who goes there?!" The three shouted back: "Company B!" After a moment, the pickets shouted out: "Company B has come back!" A cheer rippled down the column in the darkness. Sergeant Forbes rode up to Colonel Grierson and said: "Captain Forbes presents his compliments, and begs to be allowed to burn his bridges for himself." Captain Forbes caught up with a rear guard left by Grierson at a nearby bridge the next day, the 27th. They crossed together, burned the bridge, and then galloped off to rejoin the main column.

On 29 April, Grierson was forced to reconsider his plans. There was no evidence that Grant had made a landing, while captured couriers and dispatches made it clear the rebels were closing in. The only way to escape was to keep on moving south towards Union-controlled Baton Rouge.

By that time, the men were exhausted and their horses were failing. They took replacement horses from plantations and farms, but the pace was a killing one, with man and beast strained to the limits of their endurance. They moved as fast as they could, and made good progress -- only to find on 1 May their way blocked by three companies of Louisiana horse soldiers. A short fight resulted; Grierson brought up artillery and drove the Confederates off, but now the rebels were completely alert, and knew where the raiders were. Grierson drove his men all night long, detailing Captain Forbes and his men to bring up the rear, and make sure no sleep-drugged stragglers were left behind.

They were only six miles (10 kilometers) out of Baton Rouge when Grierson relented, allowing them to fall out to rest at a nearby plantation. Grierson went into the house and began to play a piano, and then was interrupted by a report that Confederate troops were approaching. Grierson didn't believe it, and went out to meet two companies of Union cavalry cautiously advancing up the road. One of Grierson's men had been carried by his horse into their camp, asleep in the saddle, and they had been sent to confirm the man's story.

The Federal commander in Baton Rouge, Major General Christopher C. Augur, was so impressed that he insisted that Grierson and his men parade through the town. Grierson tried to beg off, but General Augur wouldn't take no for an answer, and so the exhausted and dirty men were forced to spend two more hours on horseback. Some things about the military never change.

Grierson and his men had accomplished a remarkable feat, pulling off a highly effective raid that would have done justice to Bedford Forrest -- even scoring one up on him, since Forrest operated in areas where the locals were friendly to the Confederacy, while Grierson's troopers had been surrounded by hostiles. The Federals had ridden over 600 miles (960 kilometers) in 16 days, losing only 26 men while inflicting a hundred casualties on the enemy, and paroling hundreds more prisoners. They destroyed over 50 miles (80 kilometers) of rail and telegraph lines, as well as large quantities of enemy supplies.

Most importantly, they left Pemberton all but unstrung. Pemberton, despite his curt military manner, was an indecisive general, simply becoming confused when confronted by disorderly realities. His cavalry were scattered, chasing after Grierson and his men, leaving Pemberton blind to the actions of Grant, by then rapidly on the move himself. Grierson became famous in the Northern press; less than two months later, he would be promoted to brigadier general.

BACK_TO_TOP* Grant's push began early in the morning on 29 April, when Porter's gunboats engaged the Confederate batteries sited on the bluffs above the Mississippi at Grand Gulf. Although appearing enthusiastic to Grant, Porter had been writing his superiors with his misgivings about taking on these batteries, giving himself some cover in case something went wrong -- and after a half-day exchange of fire with the rebels, he had reason to believe he had been proved right. The gunboats took a severe pounding, with 75 men killed or wounded, while the Confederates remained essentially unharmed.

Grant was, as usual, undisturbed. Since it wasn't safe to cross at Grand Gulf, then he would simply cross someplace else -- though Grand Gulf would have to be dealt with soon afterward, since the rebel forces there were a threat to his rear. He organized his men for a crossing and had the steamships run downriver past the rebel batteries at Grand Gulf during the night. Lacking any intelligence on a good place to perform the crossing, he took the simple step of sending men across the river in a small boat to grab a local slave.

The slave proved to be intelligent and very cooperative, giving excellent advice on the best place for a landing. He recommended the town of Bruinsburg, pointing out that there was high ground all the way from there to the town of Port Gibson, 10 miles (16 kilometers) inland. From there, Grant's men could then advance on solid ground to attack Grand Gulf, or take whatever other actions their commander considered wise. The next morning, 30 April 1863, one of MacPherson's divisions and all four of McClernand's, a total of 23,000 men, crossed the Mississippi.

By that time, Pemberton was completely awake to the fact that he had serious trouble on his hands, but was still very much in a fog as to precisely where it was coming from. Grant had followed up Steele's feints and Grierson's raid with a third deception.

On the same morning of 31 April, Sherman performed a major demonstration near Haines' Bluff, not far from Chickasaw Bayou, where he had come to grief in December. Grant had instructed Sherman to decide for himself whether to conduct the feint. Grant had been concerned that it would not only deceive the rebels but the Northern public as well, who might consider it another defeat; Sherman had angrily replied that he cared nothing for what the papers might say. Sherman took a small fleet and the better part of a division up the Yazoo, with the men given orders to "look as numerous as possible." They marched back and forth, went around in circles, crowded the decks of steamships, repeatedly got on and off the vessels, set large numbers of campfires, played their regimental bands for all they were worth, and in general had great fun trying to excite the Confederates.

The Confederates hammered the fleet with cannon fire. They inflicted some damage on the riverboats, but all the Yankee vessels and soldiers were pulled out without incident on the evening of 1 May, having suffered few casualties. Confederate commanders on the spot recognized that the attack was a feint, and reported as much to Pemberton -- but it did much to confuse Pemberton of Grant's real intentions. By the time Pemberton sorted things out, Grant's men were on the eastern shore of the Mississippi and moving fast.

The 23,000 men that Ulysses Grant had moved east across the Mississippi on 30 April 1863 didn't match the numbers of Confederates in the region, but they were all Grant had available for the moment. Union reinforcements were on the way, but he couldn't wait for them: the rebels were confused and disoriented by the raids and diversions, and Grant wanted to keep them that way.

The first item of business for the Federals was to take out the Confederate garrison at Grand Gulf, and McClernand moved out with his corps that afternoon to deal with them. The Confederate commander at Grand Gulf, 32-year-old Brigadier General John S. Bowen -- who had once been a neighbor of Grant's in Saint Louis -- sent a brigade down the road to the far side of a town named Port Gibson to confront the Yankees. The two forces made tentative contact as darkness was falling, and so serious fighting had to wait until morning, 1 May. Bowen was completely outnumbered; he was forced to fall back that afternoon. He managed to inflict 900 casualties on the Federals, at the cost of 800 of his own men. Bowen didn't feel confident of holding out and evacuated Grand Gulf a few days later, giving Grant a little breathing space while he waited for Sherman to arrive.

Grant also had to think of what to do with his 12-year-old son Fred, who had talked his way on board the second group of ships that had run past Vicksburg. Fred had since been demonstrating considerable resourcefulness in catching up with his father. The boy arrived with Charles Dana shortly after the fighting around Port Gibson, with the two of them mounted on a pair of big old plow horses. Since telling Fred to go back home was clearly not going to work, Grant simply shrugged and let him tag along.

* Grant's original plan was to link up with Nathaniel Banks, and then their combined forces would fall on Vicksburg and Port Hudson in sequence. However, Banks replied that though he was sympathetic to the idea of a combined operation, he didn't have the transport to move his men to Grant in a useful period of time. In reality, though the lack of transport may have been a factor, Banks was worried that Confederate forces would move on New Orleans once his army had gone north to help Grant.

To Grant, Banks' refusal was just as well in some ways. Banks outranked Grant, meaning Banks would be in charge if the two generals joined forces, and Banks was certainly not the best general the Yankees had. Grant later wrote: "I therefore determined to move independently of Banks, cut loose from my base, destroy the rebel force in the rear of Vicksburg and invest or capture the city." Grant sent off a message to Halleck describing his plans, even though he knew Halleck would disapprove -- since if rebel forces in the region combined, they would well outnumber Grant's force. The message was no more than a formality, since the nearest Federal telegraph station was in Cairo, Illinois, about 400 miles (645 kilometers) upriver. By the time Halleck's response came back, Grant would be in the thick of it.

The plan did seem to have holes in it. While Grant had his men seize every farm wagon, buggy, cart, or other vehicle they could get their hands on, there was only one road leading from Grand Gulf. Sherman, having just arrived with his corps, warned Grant that it would be impossible to supply 50,000 men over a single road. Grant replied: "I do not calculate upon the possibility of supplying the army with full rations from Grand Gulf. I know it will be impossible without constructing additional roads. What I do expect, however, is to get up what rations of hard bread, coffee, and salt we can, and make the country furnish the balance." Sherman was uneasy with the idea, but decided to do what he could to make it work.

Grant's men were already expert foragers; all Grant's supply strategy meant was that they didn't have to exercise discretion in their looting, and they were energetic in their thievery. A farmer rode up to a division commander on a mule and complained that Yankee soldiers had stolen all he owned; the general replied: "Well, those men didn't belong to by division at all, because if they were my men, they wouldn't have left you that mule."

Grant's army was still poorly equipped in many ways, with men lacking blankets, tents, and sometimes even shoes. Whatever their condition, it was important to move quickly. Joe Johnston -- now the supreme commander of the Confederate Department of the West, with headquarters in Tullahoma, Tennessee -- was already sending messages to Pemberton, suggesting that he consolidate his forces and crush the Federals before they isolated Vicksburg. Confederate reinforcements were in fact already building up in Jackson, Mississippi, about 50 miles (80 kilometers) due east of Vicksburg. Grant decided to march on Jackson and drive off those reinforcements.

Pemberton remained befuddled. The Big Black river flowed southwest between Vicksburg and Jackson, to empty into the Mississippi. Pemberton assumed incorrectly that Grant intended to move directly on Vicksburg, and so began to set up fortifications west of the river to block such an advance. Pemberton moved out of Vicksburg with 20,000 men, leaving 10,000 behind for the defense of the city, and organized them behind the Big Black to wait for Grant's attack. He also ordered a brigade of 2,500 men under Brigadier General John Gregg to move from Port Hudson to Jackson, pick up the reinforcements there, and then march west to strike Grant's expected attack from the rear.

Gregg's men had reached the town of Raymond, 15 miles (24 kilometers) west of Jackson, when they made contact with McPherson's 10,000-man XVII Corps to the west of the town early on 12 May. Gregg assumed that the Federals in front of him were merely a feint and threw his men forward. The rebels hit McPherson's men hard, throwing them into confusion, almost sending them fleeing in panic. Then Black Jack Logan showed up.

36-year-old Major General John A. Logan was in command of McPherson's 3rd Division. He was a "political general", an Illinois lawyer who had become a congressman and had swung a military appointment. While many political generals were inept, Logan was a natural war leader. He was fearless, powerfully built, with a long black mustache and long black hair that gave him his nickname. Black Jack galloped into the middle of the crumbling line, and with "the shriek of an eagle", rallied his men for a counterattack. The fighting was fierce, with the muzzles of the rifles of the two sides crossing at points of contact. The Union men were now aroused; their superior numbers quickly began to roll over the rebels. By mid-afternoon, Gregg's men had been forced back to Raymond.

The Federals had suffered almost 450 casualties, the Confederates over 500. Gregg had lost a fifth of his men and knew he faced complete annihilation. He ordered his men to pull back to Jackson. The citizens of Raymond had prepared a great picnic for Gregg's men; McPherson's men found it waiting for them when they swept into town, and had a quick feast before they continued in pursuit of their defeated enemy.

BACK_TO_TOP* The next morning, Joe Johnston arrived in Jackson, after four days of roundabout railroad travel, only to find Gregg's demoralized soldiers straggling into town, with the Federals not far behind them. With reinforcements arriving, Johnston would soon have 12,000 men in Jackson, but McPherson's and Sherman's corps numbered about 20,000. The Federals had already successfully cut all communications between Pemberton and Johnston. Johnston wired Richmond: I AM TOO LATE.

On the morning of 14 May, as a drenching rain fell from the sky, Johnston began to pull his troops north out of Jackson. He left General Gregg behind with two brigades and a regiment as a rear-guard. McPherson made contact at about noon; Gregg's men managed to put up effective resistance until they were finally overrun by a howling bayonet charge. The American flag was soon flying from the dome of the state capital building in the town. The fight for Jackson had cost the Federals about 300 men, the Confederates about 200. The town fell so rapidly that the citizens didn't realize things were going badly until they saw Union soldiers in the streets.

The Yankees sacked the place: Jackson was a Confederate manufacturing center, and so had to be demolished. A reporter from the Chicago TIMES with the penny-dreadful name of Sylvanus Cadwallader wrote: "Foundries, machine shops, warehouses, factories, arsenals, and public stores were fired as fast as flames could be kindled." Sherman's men paid special attention to ruining the rail lines through the town. They tore up the tracks, lit bonfires with the ties, and softened the rails enough to wrap them around trees. The twisted rails would become a trademark of Sherman's men, being named "Sherman bowties". That night, Grant slept in the same hotel room that had been occupied by Joe Johnston the night before.

Grant's speed and decisiveness had driven a wedge between Johnston and Pemberton. It was brilliant generalship, with an inferior force falling on a component of a superior one and dealing it a blow. However, Johnston's force was still essentially intact, and the success at Jackson had to be followed up swiftly.

Grant was greatly helped in his own plans by the fact that he knew what Joe Johnston was thinking. Some time before, a citizen of Memphis had been branded a rebel sympathizer, to be thrown out of that city by Federal authorities. The man had quickly been recruited as a Confederate courier -- but the expulsion had been staged: he was a Yankee spy. Johnston had given him a message to carry to Pemberton, but the message ended up in Grant's hands instead. In the message, Johnston ordered Pemberton to link up with him and smash Sherman and his corps, which he wrongly believed was in the town of Clinton. Grant was perfectly happy to let them try. He sent the message on its way to Pemberton, then ordered McClernand to march north with his XIII Corps and get between the two rebel forces. McPherson was ordered to take XVII Corps and reinforce McClernand.

In the meanwhile, Pemberton was still confused. He first ordered his men to march south and cut Grant's supply line; then, on prodding from Johnston, he reconsidered and sent them northward, towards Johnston's forces. Pemberton's troops collided with McClernand's and McPherson's men on the morning of 16 May, at a hill on a farm owned by a local named Sid Champion.

Pemberton had 23,000 men, the Federals 32,000. Although the rebels had little warning, they managed to set up a good defensive line, making skillful use of the terrain. The Confederate defense stretched over 6 miles (10 kilometers), in the form of a vee roughly centered Champion's Hill, with a commanding view of the terrain below. The northern side of the vee was held by Major General Carter L. Stevenson; the center around Champion's Hill by John Bowen; and the southeast side of the vee by Major General William W. "Old Blizzards" Loring.

The fighting began in earnest when a Union division under Major General Andrew Jackson Smith made contact with Loring's men; the two sides quickly got tied up in a hot firefight. However, the decisive action was to the north: Grant sent Logan's division of McPherson's corps against the Champion's Hill strongpoint from the north, while most of McClernand's XIII Corps attacked it from the east. In fact, only one of McClernand's divisions managed to get into the fight, but it was led by the aggressive Brigadier General Alvin P. Hovey, the "Fighting Hoosier". The two Federal divisions went into action at about 10:30 AM. The rebels were stretched thin, and quickly gave way.

On coming to the crest of Champion's Hill, a Federal brigade under Brigadier General George F. McGinnis found themselves confronted with six rebel batteries, loaded and ready to fire. Thinking quickly, McGinnis ordered his men to fall to the ground; the guns fired a cloud of canister over their heads, and then the Union men got up and rushed the guns. A Mississippi battery managed to get off another load of canister before the batteries were all overrun and captured.

With his defense caving in, at about 1:00 PM Pemberton called on Bowen and Loring to send reinforcements to the center. Both generals protested that they were heavily threatened themselves, but Pemberton repeated the order. At 1:30 PM, Bowen moved north with his troops, though Loring stayed where he was. Bowen's men counterattacked, screaming the rebel yell, rushing the Federals with what one Union man called "terrific fierceness". They hit the Yankees hard, and the Union attack began to fall back. The Federals gave ground reluctantly: Lieutenant Colonel R.F. Barter of the 24th Indiana took the regimental colors himself to rally his men and was shot down, badly wounded. 201 of the 500 men in his regiment fell in a matter of minutes.

Grant threw in reinforcements, consisting of two brigades from McPherson's XVII Corps. One regiment among them, the 5th Iowa, threw off everything they carried except for guns and cartridge boxes and charged up the hill, shouting like madmen. As they were going up the hill, they met scores of wounded coming back down. The wounded were still excited and enthusiastic, shouting at the reinforcements to "wade in and give them hell!"

Both sides were eager for the fight, and blasted away at each other for an hour. An Iowa sergeant wrote later of the combat delirium that seized the men: "Every human instinct is carried away by a torrent of passion, kill, kill, KILL, seems to fill your heart and be written all over the face of nature." Rebel and Yankee soldiers fired until they had used up their ammunition, then stole more from the dead to keep on fighting.

On the northern side of the battle, Federal soldiers were starting to waver when Black Jack Logan showed up on his horse like a "cyclone", rallying them with language that "savored a little of brimstone." An officer protested: "The rebels are awful thick up there!" Logan replied: "Dammit, that's the place to kill them -- where they are thick!"

At about 2:30 PM, McClernand sent another division under Brigadier General Peter J. Osterhaus from the east to attack Bowen's flank. Pemberton went to Loring to personally order him to come to Bowen's aid -- but by that time, the rebel defense was crumbling and Confederate soldiers were fleeing the battlefield. All Pemberton could do was pull out fast. The Federals were moving to cut off Pemberton's line of retreat, but he managed to find an opening, leaving a brigade under Brigadier General Lloyd Tilghman as a rear guard. Pemberton's forces managed to make good their escape, since the Yankees were unable to organize for an attack on Tilghman and his men. However, Tilghman was killed by a shell fragment, making him one of the last men to die in the battle.

Loring's division was separated in the fight, but his troops finally managed to make their way to link up with Joe Johnston's force near Jackson. Although Pemberton blamed Loring for the defeat -- with some good reason, Loring having been insubordinate and less than diligent in the fight, out of his hatred of Pemberton -- Johnston defended Loring, and no action was ever taken against him.

It had been a savage battle. The Confederates took over 3,800 casualties, while Grant reported over 2,400. As Alvin Hovey was inspecting his badly-injured division, he found a group of soldiers carrying the colors of his old regiment, the 24th Indiana. He asked: "Where are the rest of my boys?" One pointed to the dead men littering the hill and replied: "They are lying over there." Hovey turned his horse away and wept. He would say: "I cannot think of this bloody hill without sadness and pride."

It was the decisive battle of the campaign, indeed one of the most decisive battles in the West. Vicksburg was, sooner or later, doomed.

* Pemberton fled over the Big Black River near the town of Bovina, about 10 miles (16 kilometers) west of Champion's hill. He took pains to build defenses on the east bank of the river, manning them with a fresh Tennessee brigade, while the rest of his badly-beaten troops went across over a bridge and on a small steamer.

The Confederate position was a strong one, and should have been formidable -- but Pemberton's men were demoralized, while the Yankees were on a roll. McClernand's men encountered the rebel defenses on the morning of 17 May, to promptly attack. The assault was led by an oversized Irish brigadier general named Mike Lawler, who was a brawler all through. Charles Dana said of him: "He is as brave as a lion, and has as much brains." Boldness was all that was needed, however, with Lawler sending his men in on a furious bayonet charge that simply swept over the Confederate rearguard; they quickly surrendered.

There were only about 200 rebel casualties, but over 1,750 were captured. There were less than 300 Federal casualties. One of the wounded was young Fred Grant, who had been nicked in the leg by a bullet. When an officer asked him what was wrong, he replied: "I am killed."

Pemberton had no choice left but to fall back towards Vicksburg, 12 miles (19 kilometers) away, with the beaten men retreating in pain and humiliation. Grant and Sherman, who had just followed up the rest of the army from Jackson, were exuberant. Sherman had no more doubts about his leader. The two rode well ahead of the body of their men to the north of Vicksburg, where they planned to set up a base.

They soon found themselves overlooking the bluffs where Sherman had come to frustration back in December. Sherman told Grant that he had felt grave doubts about the wisdom of Grant's strategy, but now he felt that he had just been through "one of the greatest campaigns in history."

That afternoon, the defeated rebels began to flood back into Vicksburg, to the dismay of the citizenry. A distressed woman asked a soldier: "Where are you going?" He replied: "We are whipped." The weary men, along with civilians fleeing the advancing Federals, continued to march into town in a state of confusion and disorganization until late that night. The soldiers and the townspeople all blamed Pemberton for the defeat.

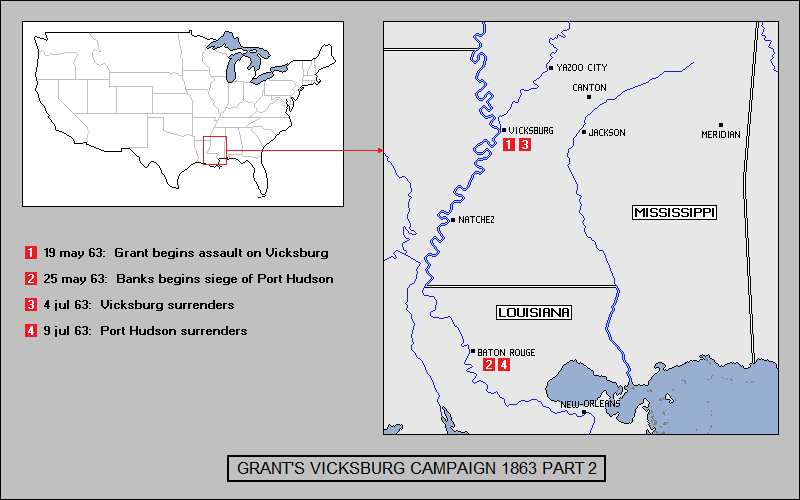

Pemberton was discouraged, but nowhere near giving up. Joe Johnston had wisely urged Pemberton to abandon Vicksburg, writing to him: "Instead of losing both troops and place, we must save the troops." However, Pemberton called a council of war, and his officers all voted to stay: they would hold Vicksburg as long as possible. Seven miles (eleven kilometers) of defenses had been built around the city, and Pemberton put his men to work bringing them to the highest readiness. Encouraged by the increasingly strong fortifications, Pemberton's men began to recover their morale. Pemberton had a total of 30,000 troops, providing him with plenty of manpower.

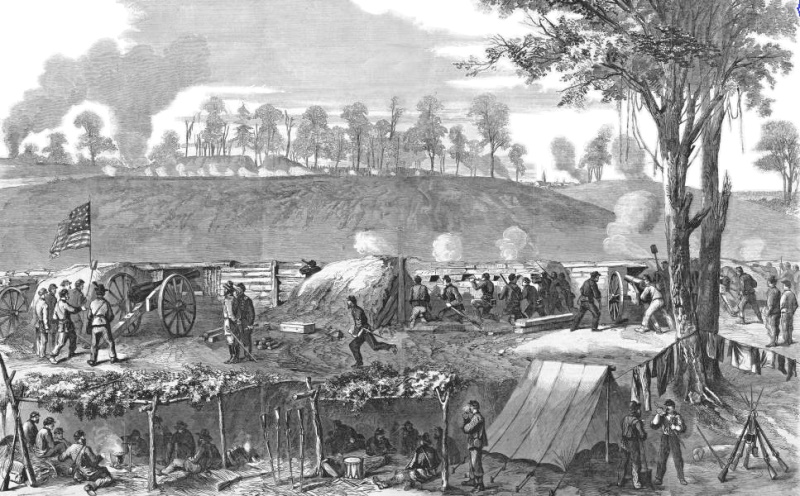

BACK_TO_TOP* Grant launched his first attack on the city's defenses on the morning of 19 May, to get a hot reception. McClernand's corps was sent in from the east, while McPherson and Sherman sent their men in from the north. The terrain was rough, covered with thick underbrush, cut by deep ravines, and littered with trees cut down by the Confederates as obstructions; the defenses themselves were well laid-out. Only Sherman's corps was able to make any progress, and not very much at that in the face of heavy fire. By nightfall, it was obvious the attack was a failure. The Federals had lost almost a thousand men, while Pemberton only lost about 250. Still, Grant wasn't discouraged, feeling confident of winning in the end. His troops, facing the ugly Confederate fortifications, didn't feel quite so confident.

For two days, Grant's men consolidated their positions around Vicksburg in preparation for an assault, clearing away obstacles and bridging ditches. A road was also built to the steamboat landing at Chickasaw Bayou. Grant's men had been living off the countryside, but a big army eats a lot, and the pickings were getting slim. A more predictable source of food and other supplies was an absolute necessity. The men were getting hungry, setting up a chant of "Hardtack! Hardtack!" -- when Grant inspected the lines. He told them that once the road was completed, there would be plenty of bread and coffee. The soldiers cheered.

Grant scheduled his second attack on Vicksburg for the morning of Friday, 22 May. After sunrise, Federal batteries and gunboats began a steady shelling of Confederate defenses that lasted four hours. At 10:00 AM, the firing faded out; masses of Union soldiers rose from their trenches, bayonets fixed, running toward the rebel defenses with loud hurrahs. The Confederates held their fire until Grant's men were well in range, then poured rifle fire and canister into their ranks. The Federals didn't have a chance. Though some of them actually made it to the edge of the city's defenses, they were too weak to hang on, and were quickly dislodged by counterattacks.

Under such brutal conditions, there were remarkable incidents of heroism. A regiment of Texans holding the Vicksburg lines mowed down the Yankees in front of them, strewing the ground with dead and wounded -- then, out of the smoke, a lone Union private, Thomas H. Higgins of the 99th Illinois, marched forward carrying the Stars & Stripes. The stress of battle had somehow overcome Higgins' instinct for self-preservation, for he marched forward over the bodies of his comrades straight toward the rebels, as if he were on parade. The Texans were astounded. Some called out: "Don't shoot that man!" Others cried: "Come on, you brave Yank!"

Higgins, having gone forward with every reasonable expectation of death, could not turn around and go back. The Texans captured him, and he became a hero even among the Confederates, who brought him before Pemberton to receive the general's regards. Higgins would be later awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, with the citation based partly on testimony by Confederates.

Even if many more Yankees had been as bold as Higgins, the attack was hopeless. Experienced soldiers recognized the futility and refused to advance; those who had advanced into range of enemy fire were dead, wounded, or pinned down in the hot Mississippi sun. By early afternoon, Grant himself had to admit that the battle was hopeless. McClernand was more optimistic, reporting success, and asking for reinforcements. Grant told Sherman: "I don't believe a word of it." McClernand insisted, and Grant ordered another push -- which predictably ended in another session of futile bloodletting. After that, nobody had any illusions that the door to Vicksburg was going to swing open easily.

Grant lost almost 3,200 men, with over 500 killed; Pemberton lost less than 500. Grant was furious at McClernand, though to an extent McClernand was a convenient scapegoat for the day's failures. In fact, in a staggering demonstration of thoughtlessness, Grant did not even bother to ask Pemberton for a cease-fire so that the Union dead and wounded could be picked up. They remained on the field for three days and Pemberton, appalled by the stench and misery in front of his lines, had to propose a ceasefire to Grant. Grant had an ugly callous streak, the suffering of his men not ranking high on his list of concerns. All he wanted was to take Vicksburg: "We'll have to dig our way in."

* While David Dixon Porter had not been able to contribute directly to Grant's whirlwind advance through Mississippi, he was thoroughly prepared to assist once the two men hooked up again.

On 20 May, Porter had sent four of his river gunboats upstream to the Yazoo to ensure that the Confederates were not preparing another nasty surprise like the ARKANSAS. They were -- but when the Yankee gunboats returned on the 23rd, they reported that the rebels had burned their naval yard at Yazoo City on the approach of the Federals, destroying three warships under construction. That was satisfying, though Porter wasn't inclined to let the pressure off the rebels; he sent the gunboats back upstream to destroy steamships, sawmills, and anything else of value. When the gunboats returned, the Confederates had no means of resupplying Vicksburg by water, even if the way had been cleared.

With the siege of the city under way, Porter set his sailors to assisting in the bombardment, but matters did not go quite as easily. On 27 May, Porter sent the CINCINNATI to investigate a suspected rebel artillery battery near the Vicksburg landings, and found that artillery battery to be only too alive and well. The CINCINNATI took several hits and sank; 20 of her crew were killed and 14 were wounded. Porter, knowing war involved losses, took the sinking of the gunboat casually. He kept other gunboats pounding the besieged rebels in Vicksburg.

Downstream at Port Hudson, Nathaniel Banks was engaged in a fight of his own that echoed the battle upriver. On 14 May 1863, he put his forces on the move, marching from Alexandria, Louisiana, towards the Mississippi, where they would move south down the west bank of the river, and cross a few miles north of Port Hudson.

Banks did not accompany them. He took a train to New Orleans, intending to take Union forces in Baton Rouge up the Mississippi to catch Port Hudson in a pincher movement between troops marching north and south. Although coordinating the movements of two widely-separated forces is notoriously difficult, Banks pulled it off. The two forces met up on schedule on 25 May and encircled the town. On 27 May 1863, Banks launched a full-scale assault.

The rebel garrison at Port Hudson was under the command of Major General Franklin Gardner, a Northerner from Iowa who had married a Louisiana woman and sided with the South. His command had been reduced by desperate calls for manpower to fight Grant to less than 6,000 men. In fact, Gardner had withdrawn from Port Hudson on 4 May, only to be told to return. Joe Johnston had then written an order on 19 May to instruct Gardner to pull out again -- but by the time the order reached Port Hudson, Gardner was surrounded.

Banks was in a hurry to take Port Hudson. He believed that the rebels might be taken off balance by a fast and furious assault, and besides, he had only left a skeleton force behind to hold New Orleans; if the rebels decided to move against the city, they could cut him off at the rear. The attack began with a bombardment by 90 guns, assisted by the fire of Farragut's fleet. Farragut had been at Port Hudson since 8 May, when he had bombarded the place for three days, to very little effect. Despite the poor results of the earlier bombardment, Farragut rarely turned down a fight, and his sailors did all they could to help.

The bombardment went well -- but when the Union soldiers went forward, they found themselves in a maze of ravines, choked with fallen timber and tangled magnolia groves, to be pounded by heavy grape and canister fire from the defenders. The Confederate defenses were skillfully laid out and murderously strong. One of the Federals later called the battle a "gigantic bush-whack". By noon, the attack was clearly fizzling; Banks still was determined to press on, even as his chances were fading. The attacks were futile, though his two black regiments, the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards, in the first trial of black Union troops in a major battle, acquitted themselves well under wretched circumstances, losing a quarter of their number.

At the end of the day, the Federals had suffered 1,995 casualties, in contrast to 235 Confederates. One of the Union wounded was Brigadier General Thomas Sherman, whose division had somehow not been informed of the attack plans. After a blistering dressing-down by Banks, Sherman led his men into battle on his horse, and quickly lost his leg. Riding tall in front of his men was grand and courageous -- but as most officers still among the living had realized by then, it wasn't very practical. Banks quickly called a truce with Gardner, so that the Union wounded could be collected off the battlefield; then asked for, and was granted, an extension when the ugly job of picking up the dead and wounded proved more laborious than expected.

The losses convinced Banks that the defenses of Port Hudson were almost "impregnable", as he wrote Grant, and he added very fairly that his men had "done all that could be expected or required of any similar force." He asked Grant for a brigade of reinforcements if it could be spared, though Banks knew that was unlikely. He remained determined to take Port Hudson, and like Grant upriver settled in for a siege, putting his men to digging siegeworks and pounding the Confederate fortress with shot and shell.

* North up the river around Vicksburg, Pemberton and his men were now bottled up in the city, and its fall was clearly only a matter of time. Grant was once more the man of the hour. Newspapers that had been abusing him for months now could not praise him enough. Sherman was properly disgusted, writing to his wife: "Grant is now deservedly the hero. He is now belabored with praise by those who a month ago accused him of all the sins in the calendar, and who next week will turn against him if so blows the popular breeze. Vox populis, vox humbug."

More significantly, Grant's men now had solid faith in their leader. Halleck, who had been making Grant's life miserable, became fully supportive and was sending heavy reinforcements. They were needed: the Union lines around Vicksburg were 12 miles (19 kilometers) long, and Grant's 50,000 men were stretched thin. By early June, 20,000 more troops had arrived. A Confederate observed that "a cat could not have crept out of Vicksburg without being discovered."

BACK_TO_TOP