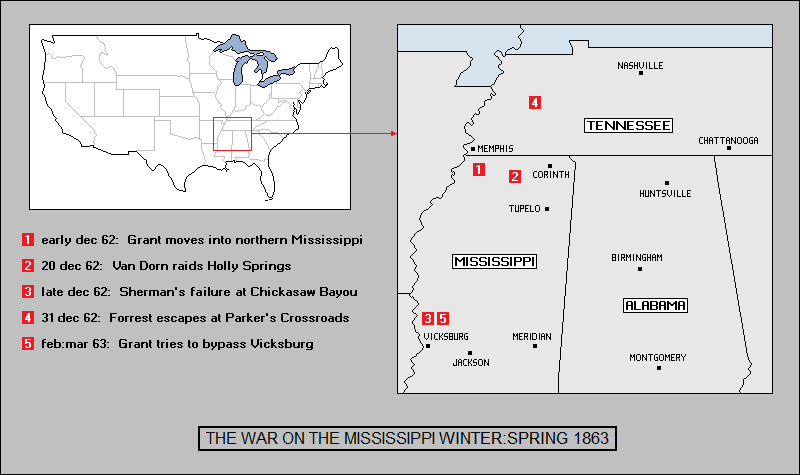

* The war along the Mississippi began to heat up in the fall of 1862. The Confederates were the first to move, attacking the Union base at Corinth, Mississippi, in early October -- with disastrous results for the rebels. In December, General Grant attempted to move on Vicksburg, but the effort was derailed by rebel cavalry raiders, and an energetic Confederate defense at Chickasaw Bayou. Grant assessed his mistakes and learned from them.

* Confederate General Earl van Dorn was an ambitious man, and accordingly decided to move on the Federal base at Corinth. Sterling Price, following his retreat from Iuka, linked up with Van Dorn, which gave Van Dorn 22,000 men in three divisions. He planned to lead them north towards western Tennessee as a deception, and then turn abruptly east to fall on Corinth.

Van Dorn had "reasonable" expectations of success. Price was happy with the plan as well, and looking forward to a battle. Although Price had got the better of the Yankees at Iuka, he'd been forced to make a hasty exit, and had been idle since then. Unionist editors were calling Price "Old Skedad", and commented, in reference's to Price's hefty size, that "as a racer he had seen few equals for his weight." They even called him a "West Pointer" -- an unjust slur that his defenders were quick to deny.

Unfortunately, Van Dorn's guarded optimism was based on misperceptions. Grant was absent, having gone to Helena, Arkansas, to discuss cooperation between Union forces on the two sides of the Mississippi; he had left Rosecrans in charge in Corinth. Rosecrans was perfectly aware that the rebels might attack Corinth, and so he had concentrated his forces in the town. Van Dorn's intelligence told him there were 15,000 Federals in Corinth, but in reality there were 23,000 in four divisions, meaning the defenders outnumbered the attackers. True, many of Rosecrans' soldiers were untrained, and since Corinth was a filthy pesthole, many of his men were ill and demoralized.

To make matters worse for Van Dorn, he had received intelligence from a woman of Corinth that described the town's defenses. The woman's message was correct as far as it went -- but it had been intercepted by Union General Ord, who sat on it a while and then sent it on, unchanged, after the defenses had been greatly strengthened with a double set of earthworks.

Van Dorn's and Price's forces had joined together in the town of Ripley, about 30 miles (48 kilometers) southwest of Corinth, on 28 September. They moved north to reach the town of Pocahontas on 1 October, where they turned east as planned. They had to move quickly; the summer's drought had dried up all sources of water on the road from Pocahontas to Corinth, and besides, Rosecrans now knew what Van Dorn was up to.

The Confederates reached the outer earthworks of the Corinth defenses on 3 October 1862 and promptly attacked. After a half day's fighting, they managed to dislodge the Federals from their forward positions and take a few artillery pieces. However, the rebels had paid dearly for their gains, for the Yankees fought stubbornly and fell back only when forced to. Van Dorn's men still kept up the pressure; by nightfall, they were before the defenses around the town itself. Both Van Dorn and Rosecrans expected to renew the battle in the morning, and both expected to win. They had a long-standing rivalry that went back to West Point, having both graduated in 1856, with Rosecrans fourth from the top of the class, Van Dorn fourth from the bottom.

Before dawn on 4 October, Van Dorn's artillery opened up on the Federal positions. Union batteries immediately replied, rising to a noisy duel that one Union general with a romantic touch found "grand", like the "chimes of old Rome when all her bells rang out." The firing died down to occasional pot-shots from sharpshooters -- snipers, in modern terms -- after sunrise. Rosecrans was puzzled, and told a colonel to take his regiment out to investigate: "Feel them, but don't get into their fingers." The colonel was full of steam and replied: "I'll feel them!" He took out his regiment to probe the forest outside the town, and was immediately hit with a volley that cut up his regiment, sending the soldiers packing. The colonel was wounded and captured.

At 10:00 AM, Van Dorn sent his men in with a full-scale assault that was met by a storm of cannonballs, shells, and canister, inflicting terrible casualties on the attackers. An Alabama lieutenant wrote later: "Oh God! I have never seen the like! The men fell like grass." Three regiments in the center of the charge did manage to pierce Federal lines, taking a terrible volley from Federal troops firing from the rear that sent rebels falling down in "ghastly heaps"; some managed to even make it into the heart of the town itself. It was brave but futile. The Yankees were pressing them still, threatening to cut them off, and all the rebels could do was fight their way back out of the town again.

By noon, it was over. Van Dorn's men had taken enough punishment and were falling back off the battlefield; Price wept as he saw his decimated regiments limping away from the fight. By 1:00 PM, Van Dorn was leading them from Corinth along the same road they had come, leaving the dead and badly wounded behind. A Federal wrote of the scene in front of one strongpoint: "The ground was covered so quickly with gray coated men that one could scarcely step without stepping on them. The ditch was literally full and the parapet covered as thick as they could lie -- in some places two or three deep."

Rosecrans did not follow, though Grant had ordered him to pursue if the battle went his way. Rosecrans wanted his men to get some rest, thinking they could pursue the Confederates in the morning. Grant was disgusted with Rosecrans' indifference, sending a force of 8,000 men south from Bolivar, Tennessee, to intercept Van Dorn. They succeeded in catching up with the rebels the next day, 5 October, resulting in a short, nasty little battle that left about 600 killed and wounded on each side. The Confederates doubled back towards Corinth, then took an unguarded side road that ultimately led them back to Holly Springs. Rosecrans had by this time begun his pursuit but took the wrong road, and the rebels slipped past him.

Van Dorn had lost almost 5,000 men, while inflicting only 3,000 casualties on the Federals. An immediate public cry went up for his blood, critics citing his "negligence, whoring, and drunkenness." A court of inquiry would be called at Van Dorn's request in November to investigate. It would exonerate him of all blame -- but, as a Mississippi senator wrote Jefferson Davis, as far as the citizens of the state were concerned, "an acquittal by a court-martial of angels would not relieve him of the charge."

Whatever the case, Van Dorn had been badly beaten. The afternoon after the battle of Corinth, Rosecrans rode over the battlefield, encouraging his men and chatting with rebel prisoners -- a practice for which he had an odd fondness. He found an Arkansas lieutenant propped up against a tree and with a bullet through his foot, and commented on the sad litter of dead lying about that there had been "pretty hot fighting here." The lieutenant replied: "Yes, General, you licked us good. But we gave you the best we had in the ranch."

BACK_TO_TOP* Van Dorn's clear failure at Corinth figured in calculations that had already been in progress in Jefferson Davis's mind for the past two months. The calculations had been set in motion by a set of far-flung circumstances. The first was the problem the citizens of Charleston, South Carolina, had with their current military commander, General John C. Pemberton.

The 48-year-old Pemberton was something of an odd quantity. He was a Pennsylvanian by birth, but dedicated to the South and the Southern cause. He was devoted to the concept of States' Rights, and had married to a Virginia woman. Pemberton was still an outsider, all the more so because he had never acquired Southern gentility, remaining blunt and curt. He had been placed in command of Charleston's defenses, but although he was industrious, he was also overbearing and inflexible. He often stepped on toes, and the prominent citizens of the city wanted to get rid of this not-quite-a-Southerner.

The second of these circumstances was the peculiar position of the General Beauregard, who had been on sick leave at Bladon Springs, Alabama. In June 1862, after organizing the evacuation of Corinth, ill health had forced him to give up his command, with Braxton Bragg taking his place. Beauregard had been the Confederate commander in Charleston before Pemberton, and the Charlestonians wanted him back. Although the relationship between Beauregard and Jefferson Davis was distinctly frosty, Davis finally decided to give in to the Charlestonians, with Beauregard receiving orders to proceed to Charleston in early September. He arrived by train on 15 September, receiving a hero's welcome. He would never again fight in the West.

Having moved that piece, Davis then moved the one displaced. Pemberton was to take command of the Department of Mississippi, organized on 1 October, and direct the defense of Mississippi and the free portions of Louisiana against further aggression by the Federals. Pemberton arrived in Jackson, Mississippi, on 14 October to take charge. He had a difficult task. There were only about 50,000 men in his command, including the cut-up and demoralized Trans-Mississippians under Van Dorn and Price, plus the garrisons of Vicksburg and Port Hudson. They had to defend the region from much larger Union forces to the north and south. Davis felt the inflexibility that had made Pemberton so unpopular in Charleston would be a positive asset in his new post. It was a big gamble.

Van Dorn, not surprisingly, was very upset at being passed over for the job in favor of an imitation Southerner who hadn't seen any fighting since the Mexican War -- but Davis managed to soothe him by assuring him that with Pemberton in charge, he, Van Dorn, would be able to direct his energy on taking the offensive against the Yankees. That was not just soft talk from Davis; if Van Dorn had proven rash in his capacity as an army commander and his men had paid bitterly for it, that sort of willingness to take big chances was often a virtue in a cavalry commander. Van Dorn was put in charge of Pemberton's cavalry, where he would indeed prove highly enthusiastic and effective.

* There were command shufflings among the Federals as well at the time. General John McClernand, nominally under Grant's command but chafing at circumstances that left him little opportunity for military glory and personal advancement, had gone to Washington in late September to propose a plan of action to President Lincoln.

McClernand had access to Lincoln, since both had not only been sent to Congress from Illinois, but also had worked as lawyers in that state. McClernand suggested to the President that a new levy of Illinois troops be raised and that he, McClernand, lead them down the river and seize Vicksburg. Lincoln -- frustrated in his attempts to get regular army generals to move against the rebels, and taking account of McClernand's political influence in their mutual home state -- approved the plan. However, McClernand had gone over the heads of General Halleck and War Secretary Edwin Stanton to make his case to the President; Halleck had objected to the scheme, only to be overruled. McClernand's insubordination was not forgotten by either Stanton or Halleck.

McClernand received secret orders from Stanton on 21 October, authorizing him to raise troops from the states of Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa for an expedition against Vicksburg, with the important constraint that these forces not be required by General Grant. McClernand was delighted, and set out at the end of the month for Illinois, to begin raising troops.

Grant knew nothing of this, at least for the moment. He was preoccupied with the challenge of maintaining an over-extended army in enemy territory, and had given some weight to his fears. When Halleck had sent him a message asking why he hadn't pursued Van Dorn after the battle of Corinth, living off the land to support his men, Grant replied that such an action would result in disaster. That was an odd reversal, with the usually inert Halleck urging action, and the usually energetic Grant dragging his feet. It was entirely unlike Grant, and an indication of how discouraged he had become over the hot, dry summer.

Near the end of October, Grant received news that helped put the wind back into his sails. He was sent orders clearly designating him as commander of the Department of the Tennessee, giving him authority along the Mississippi from Cairo on down to rebel-held territory. Another order sent Rosecrans to take command of the Union Army of the Cumberland in Nashville gave Grant further relief, since he had found Rosecrans pigheaded and insubordinate, and had been considering sacking him. Rosecrans had been no happier with Grant -- and in fact, the day before Rosecrans had received orders for Nashville, he had written Halleck to ask for a transfer.

In addition, Navy Secretary Welles was not happy with Flag Officer Captain Charles H. Davis, in charge of the river fleet. Davis was a very pleasant man of considerable intellectual capacity -- but to Welles, his lack of initiative in the river operations against Vicksburg demonstrated he lacked the will to fight. On 1 October, Davis was kicked upstairs, likely to his relief, to the Bureau of Navigation, where his skillset would be put to better use. Davis was replaced by David Dixon Porter, now a rear admiral.

That was somewhat surprising, since Porter lacked seniority and Secretary Welles had plenty of experience with him, being fully aware that Porter was an egotistical blowhard and an organizational backstabber -- indeed, Porter had lobbied to replace Davis. In compensation Porter was brave, energetic, resourceful, and aggressive, which Welles saw as greater virtues than his faults, and so on 9 October, Porter was given responsibility for the Mississippi squadron. On 15 October 1862, he arrived in Cairo, Illinois, to take charge of the 125 vessels, 1,300 officers, and 10,000 men of the river fleet.

* A third command shuffle came down from the top. Since the fall of New Orleans, the city had been under the command of Ben Butler. His rule there had been heavy-handed, earning him hatred through the South; and tainted with corruption, though Butler was much too slick to let anything stick. He had no abilities as a warfighter. He was still far too useful as a prominent Democrat in the service of a Republican administration to be simply sacked, and he was a skilled administrator.

Lincoln believed he had the ideal solution right at hand, in the form of Major General Nathaniel Banks, another Massachusetts politician in uniform, at the time in charge of the defenses of Washington DC. Up to then, he hadn't demonstrated much ability as a warfighter either, but he was honest, and he was well more interested in fighting battles than Butler. Possibly he deserved another chance? The conclusion was to swap Butler for Banks; on a political basis, it was an even trade.

On 8 November 1862, Banks was given orders placing him in command of the Department of the Gulf, and the next day Halleck sent him instructions detailing his agenda. Banks was to move on Mobile and Vicksburg; then Jackson, Mississippi; then the Red River; and, all that done, on to Texas. That was a remarkable set of expectations for an amateur general who had never won a battle, but Banks was enthusiastic. He was told that he would be given 20,000 reinforcements, and fairly delighted Lincoln with his energy.

BACK_TO_TOP* Grant had, for the time being, lost the energy that he had demonstrated up to Shiloh; in fact, he was proving a annoyance to the Lincoln Administration. The Union Army drew profiteers along in its wake, such creatures having few friends among the military command -- except as much as they could buy them. Grant found the profiteers a nuisance. When his father, Jesse Grant, came downstream from Illinois in the company of some eager cotton speculators by the name of Mack, Grant's patience snapped.

That might have not been so harmful, except for the fact the Macks were Jewish. Grant greatly overreacted: in early November 1862, he issued an order evicting all the Jews from his military department, without regard for their actual activities or social status: "The Jews, as a class violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department and department orders, are hereby expelled from the department within twenty-four hours of from receipt of this order."

Even in a more blatantly prejudiced era, Grant had gone way too far. Rabbis blasted the order, Jewish organizations protested -- and most importantly, a Jewish Kentucky Unionist from Paducah named Cesar Kaskel took a train to Washington, and had a personal audience with the President. Lincoln wrote out an order in Kaskel's presence instructing Halleck to see to it that the order was immediately rescinded. The order was formally canceled the next month.

The only practical result had been to embarrass Grant and diminish his credibility. After the butchery at Shiloh and his recent indecisiveness, Grant's position was becoming increasingly weak. He was known to have a history of problems with alcohol, and rumors emerged that he was hitting the bottle again.

Grant was in need of a wake-up call. He got it when he learned of the "mysterious rumors of McClernand's command." Grant didn't know any specific details about the secret army that John McClernand was raising to seize Vicksburg. In fact, even Halleck wasn't let in on the plan -- though, since he oversaw army logistics, he had an idea that something was going on. However, when Grant saw troops accumulating in his district that he knew nothing about, he knew that some threat to his authority was in progress. He wired Halleck in Washington DC on 10 November:

AM I TO UNDERSTAND THAT I LIE STILL HERE WHILE AN EXPEDITION IS FITTED OUT FROM MEMPHIS, OR DO YOU WANT ME TO PUSH AS FAR SOUTH AS POSSIBLE? AM I TO HAVE SHERMAN UNDER MY ORDERS, OR IS HE RESERVED FOR SOME SPECIAL SERVICE?

Halleck responded immediately:

YOU HAVE COMMAND OF ALL TROOPS SENT TO YOUR DEPARTMENT AND HAVE PERMISSION TO FIGHT WHERE YOU PLEASE.

That sounded decisive, and Halleck had many good reasons to back Grant against McClernand. McClernand's orders had specifically stated that he only had authority over the troops he had raised if they weren't needed for other operations in the department, which gave Halleck considerable leverage over him. However, Grant knew Halleck only too well, and was not entirely reassured.

This insecurity did Grant some good, since he got moving again. On 13 November, his cavalry entered Holly Springs, Mississippi, since evacuated by the rebels, with Union infantry columns just behind the cavalry. Holly Springs became a Union supply dump, a stepping-stone for an advance down the line of the Mississippi Central Railroad that would cut off Vicksburg and leave it to fall into his hands. Or so Grant believed.

Trouble was brewing for him. The rebels were not sitting idle, waiting for the Federals to do something. On 10 December 1862, Brigadier General Nathan Bedford Forrest -- a cavalry commander, an extraordinarily competent warfighter despite his lack of military background -- received orders from Braxton Bragg instructing him to "throw his command rapidly over the Tennessee River and precipitate it upon the enemy's lines, break up railroads, burn bridges, destroy depots, capture hospitals and guards, and harass him generally."

Bragg's general idea, conceived in response to a request by General Pemberton in Vicksburg, was to cripple Grant's ability to conduct offensive movements into northern Mississippi. The orders were music to Forrest's ears -- he couldn't have received orders more in tune with his mindset if he had written them himself -- and he left immediately with 2,100 men, mostly new recruits armed with homely weapons such as flintlocks and shotguns. He took his men across the Tennessee to the town of Clifton on 14 December using two flatboats he had constructed, and then flooded the boats in a nearby creek to hide them.

The crossing was observed by the Federals, and on 15 December Grant was told of it in a telegram from the commander of the Federal garrison in Jackson, Tennessee. Grant, not normally overly impressed by the Confederates, regarded Forrest as extremely dangerous, and in a position to do the Union cause enormous harm. As it turned out, Grant was not exaggerating the threat.

* Spurred by the activities of his rival, General McClernand, Grant had been as aggressive as he could in the winter weather. By early December, Federal advance forces had reached the town of Oxford, Mississippi, 40 miles (64 kilometers) south of the Tennessee border.

Grant was not actually moving on Vicksburg, however. The land offensive was intended to provide backup and diversion for an amphibious assault down the Mississippi. David Porter's fleet was to transport some 30,000 men under the command of General Sherman and land at a place called Chickasaw Bayou, up the Yazoo river north of Vicksburg. The terrain featured steep bluffs that would be a difficult prospect if they were adequately defended, but Grant hoped he would keep the Confederates distracted, allowing Sherman and his men to make their landing and then fall on Vicksburg.

Porter sent a small fleet of three ironclads and two lightly-armored "tinclads" down the Mississippi in early December to clear out Confederate fortifications and obstructions that might impede the stream of transports carrying Sherman's men. The rebel defense of the waters was in charge of Isaac Brown, skipper of the now-lost ARKANSAS. As resourceful in defense as he had been in offense, he improvised "torpedoes" -- naval mines, in modern terms -- out of big whiskey jugs filled with gunpowder and fuzed with cannon primers, anchored an arm's length below the surface of the muddy water.

Confederate torpedoes were not noted for their reliability, but despite the improvised nature of Brown's torpedoes, they proved effective. On 12 December, while the little Union fleet moved up the Yazoo, firing on rebel positions on the banks and fishing the deadly whiskey bottles out of the river, the ironclad CAIRO hit one and sank in eight minutes, leaving only the tops of her twin smokestacks sticking out of the water. Lieutenant Commander T.O. Selfridge, the ship's captain, got his men out efficiently, and there were no casualties. The four remaining ships ended their work and went back downstream to the mouth of the Yazoo, where Porter, just having arrived from Memphis, was waiting for them.

Selfridge, apprehensive about his commanding officer's reaction to the loss of one of his ships, requested a court of inquiry. Porter merely replied: "Court! I have no time to order courts! I can't blame an officer who puts his ship close to the enemy. Is there any other vessel you would like to have?"

For whatever Porter's other faults, he was absolutely no bureaucrat, and honestly cared about the men in his command. Selfridge, likely astonished by this reaction, wasn't quick enough to reply before Porter turned to the captain standing on the bridge: "Breese, make out Selfridge's orders to the CONESTOGA." Despite the loss, the Federals accomplished their objective: the river had been cleared for the attack on Vicksburg. Incidentally, the CAIRO would be raised a century later, and is now on display in Vicksburg.

BACK_TO_TOP* The rebels were determined to hold Vicksburg. Jefferson Davis had ordered Braxton Bragg to send reinforcements to Vicksburg from his base at Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Davis himself arrived at Vicksburg in the company of General Joe Johnston on 19 December. On 21 December, the two men took a train to Grenada, 60 miles (96 kilometers) south of Oxford, where Pemberton was in command of his forces in the field.

Davis and General Johnston were not particularly good traveling companions, the two men having a long history of quarrels. At Grenada, the bickering between them flared up again. Pemberton wanted to fight a defensive battle, building Vicksburg into an impregnable fortress, and Davis agreed. Johnston, in contrast, favored a war of offense, taking on the Federals and defeating them in the field. Johnston and Davis left with their disagreement unresolved, and the strategy for the defense of the region remained uncertain.

Pemberton had not been thinking in entirely defensive terms, however. Even before the arrival of his two superiors, he had ordered General Van Dorn to strike into the rear of Grant's army at Holly Springs, now the main supply depot supporting the Federal advance into Mississippi. Van Dorn, always enthusiastic, rode off with his men in search of the glory that had so far evaded him. He left his base at Grenada, Mississippi, on 18 December, moving north with 3,500 cavalrymen.

Grant was overextended, reliant on a single and vulnerable supply line, and well aware of the weakness. He sent warnings to his commanders to be prepared for surprise attacks. Unfortunately, the Union commander at Holly Springs was Colonel Robert Murphy, who had so quickly given up at Iuka three months before. Van Dorn's troopers stormed into Holly Springs on the morning of 20 December, achieving complete surprise -- despite the fact that Murphy had received a warning that Van Dorn was on the move. Most of the 1,500-man garrison surrendered without firing a shot, though an Illinois cavalry regiment boldly fought their way out. Van Dorn's men had a party with all the loot, and burned supplies worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. They missed the opportunity of capturing Julia Dent Grant, General Grant's wife, who had left Holly Springs to join her husband in Oxford the day before. Of course, it seems unlikely that good Southern gentlemen would have chosen to do something so impolite as to haul her off to prison.

* Forrest was having equally good luck. On 18 December, his men encountered a force of Yankees under Colonel Robert G. Ingersoll, who fell back to the town of Lexington, Tennessee, and fought it out with the rebels attacking from their front. Suddenly, Forrest's troopers appeared from all sides and swept down on the Federals, capturing Colonel Ingersoll and 150 of his men, while the rest scattered west towards Jackson, Tennessee, 25 miles (40 kilometers) away.

Forrest knew the defeated men would carry wild stories of Confederate strength to Jackson with them. He quickly encircled the town, his men making dramatic demonstrations, pounding on drums, and in general acting as noisy and aggressive as possible. The reason for the show was because the rebels were outnumbered four to one, and Forrest knew they had no chance of taking the place by brute force. The ruse worked. Intimidated by all the commotion, the commander at Jackson, Brigadier General Jeremiah Sullivan, braced for a last-ditch defense. The noisy demonstrations increased all day during 19 December, but at dawn on the 20th, the sun came up to show no rebels in the vicinity. Sullivan realized he had been tricked, and set off east after Forrest.

Or so he thought; in reality, Sullivan had been conned again. Forrest had left a false trail and was actually moving north. He never believed in fighting battles except on his own terms, his actual objective was to cut Federal communications, and his men did the job enthusiastically. They destroyed the Mobile & Ohio rail line between Jackson and Union City, near the Kentucky border, by tearing up track, wrecking culverts, burning ties and bridges, snatching up Union outposts, and in general doing enough damage to leave the rail line out of operation for the time being. Taking a break on Christmas day, Forrest reported back to Bragg that he had killed or captured 1,300 Federals at a cost of only 22 men, indicated his satisfaction with his troopers.

Under assault by Van Dorn and Forrest's fast-moving raiders, Grant's plans were coming unraveled. With Holly Springs in ashes, he had no supplies to continue his offensive; and with the rail lifeline north to Kentucky unstrung, he couldn't get any more supplies either. He would have to fall back to Memphis.

Grant typically thought more about what harm he could do to the enemy than about what harm they could do to him, and if Van Dorn and Forrest were in his rear, that meant he was in theirs as well: he could catch both of them and put them out of business for good. Orders went out to Federal units in north Mississippi and west Tennessee, putting them in motion to search out and bag the rebels, with Grant making his intentions clear: "I want those fellows caught, if possible."

There were other tasks to take care of. He ordered Colonel Robert Murphy dismissed from the service for his "cowardly and disgraceful conduct at Holly Springs." Much more important was getting word to General Sherman that the amphibious assault on Vicksburg could hope for no support from Grant's forces, and should be called off. With telegraph and rail lines cut, all Grant could do was dispatch a courier to Memphis, and hope the rider got there in time.

BACK_TO_TOP* Sherman had in fact departed downstream with three divisions from Memphis on 19 December. On the 21st, while loading up another division at Helena, Arkansas, he received reports that rebel cavalry had captured Holly Springs, but since he lacked details or confirmation, he continued on course with his plan.

If the breakdown in communications was an inconvenience to Sherman, it was a bigger one to General McClernand. Still up in Springfield, Illinois, he had been nagging Washington for three weeks to be granted the authority to take to the field with the forces he had raised. After a personal message to the President, he was informed that orders were on the way, designating him as commander of Grant's XIII Corps. McClernand was distressed, taken somewhat by surprise at finding himself still under Grant's command. He was still more angry and distressed when the orders that Grant were to send him didn't show up. Grant had actually been punctual in cutting the orders and sending them out, but Forrest had been even more efficient in cutting Grant's telegraph lines, and the orders went nowhere.

In any case, Sherman's expedition proceeded downstream. There were over fifty transports in the Union fleet -- summarily requisitioned from steamboat companies upriver -- escorted by three river ironclads, two wooden gunboats, and a pair of rams. They would join the four gunboats already at the scene. On Christmas Day, 25 December 1862, Sherman put a brigade on shore about ten miles (16 kilometers) north of the mouth of the Yazoo at a place called Milliken's Bend to wreck a section of railroad. The next day, the fleet proceeded ten miles (16 kilometers) up the Yazoo itself, soldiers alert on the decks for sharpshooters, to make a landing at a place called Johnson's Farm, north of Vicksburg, another ten miles away.

The soldiers came ashore to find the swampy country dark, confusing, and intimidating. They would have found it even more sinister if they knew that the Confederates had plenty of advance warning of their arrival. Before the war, a planter had installed his own private telegraph line along the west bank of the Mississippi, running over 40 miles (64 kilometers) along Vicksburg on the opposite shore. The rebels had an observation post at the northern terminal, and at about midnight on Christmas Eve, a soldier named Philip Hall, who was manning the Vicksburg end of the line, got a telegram:

GREAT GOD, PHIL, EIGHTY-ONE GUNBOATS AND TRANSPORTS HAVE PASSED HERE TONIGHT.

Hall managed with considerable difficulty to get to Vicksburg across the river, where he found the commander of the city's defenses, Major General Martin Luther Smith, at a Christmas Eve ball in the home of a local physician. On receiving the news, Smith paled and shouted out: "The party is at an end!" At the time Smith had only about 6,000 men, but with advance warning, by the time the Federals had landed he had managed to get 6,000 more men from Jackson, Mississippi. 13,000 more were on the way.

On 27 December, Confederate resistance began to materialize. Rebel sharpshooters began to pick off Union soldiers -- including Brigadier General M.L. Smith, one of Sherman's division commanders, who took a bullet in the hip, putting him out of the fight. When Commander William Gwin took his ironclad BENTON to blast rebels out of their hiding places in the woods, the ship ended up trapped in a narrow stretch of water where it could not evade the fire of an enemy battery. The BENTON was hit at least thirty times, with three of the shots going through gunports to tear up the crew badly. Gwin, who refused to take cover, was mortally wounded by a solid shot that tore away his right arm and much of his chest.

The casualties added to the disorientation of the soldiers on the ground. Johnson's Farm was nothing more than a clearing in the middle of swampy woods, surrounded by three bayous. Getting tens of thousands of soldiers organized for an attack on the bluffs to the south, where the rebel defenders lurked, was an exercise in confusion. A bridge was built across the wrong bayou, and companies got separated from their regiments. If Sherman had been expecting to surprise the rebels, he had failed. The men spent all of 27 and 28 December in disorganization and delay, and tentative probes on the 28th towards the bluffs to the south of the bayou flatlands drew heavy Confederate artillery fire. The rebels, under the command of Brigadier General Stephen D. Lee, were wide awake and ready for trouble.

* It wasn't until Monday, 29 December, that the attack got underway, or more accurately tried to get underway. Sherman had wanted all four divisions to make a simultaneous attack on the bluffs -- but between the confused terrain, their own disorganization, and rebel fire, only a single brigade managed to get across Chickasaw Bayou and make contact with the enemy.

The brigade was under Frank Blair JR, previously a Missouri congressman from the influential Blair family, now a brigadier general under Sherman. The Union men advanced rapidly and boldly, only to find themselves in a savage crossfire that cut down hundreds. One regiment made it all the way to the edge of the bluffs, but the Federals could advance no further under the rain of fire from the rebels.

They remained pinned down until nightfall, and then managed to trickle back "one at a time", as Sherman put it. He concluded, realistically: "Our loss had been pretty heavy, and we accomplished nothing, and had inflicted little loss on the enemy." The Federals had lost almost 1,800 men, the Confederates a little more than 200.

Sherman was not going to give up easily. He had commented before ordering the disastrous charge on the bluff: "We will lose 5,000 men before we take Vicksburg, and we may as well lose them here as anywhere else." He decided to load one of his divisions on transports and take them up the Yazoo to perform a diversionary attack at a place called Haines' Bluff. The civilian captains of the steamship transports were by that time wishing they hadn't signed on for the job; Sherman had to place armed guards on them to motivate them to stay at their posts.

Porter, always energetic, was supportive, even going so far as to suggest that one of the steam rams be sent ahead to clear out any Confederate torpedoes that might be in their way: "I propose to send her ahead and explode them. If we lose her, it does not matter much." The captain of the ram was less casual about the idea; he proposed rigging the vessel with a long boom fitted with improvised minesweeping tackle, and Porter agreed. The minesweeper and the transports set out in the moonlight on the night of 31 December. The sound of their attack was to signal another assault on the bluffs by the three divisions remaining downstream.

It never happened. At about 04:00 AM on New Year's Day, Sherman got a note from the expedition explaining they were completely fogbound, and could go no further. Sherman then assessed his situation. There was no trace of Grant; Sherman could hear the sounds of trains arriving at Vicksburg, almost certainly bringing in Confederate reinforcements; and the rain was beginning to come down heavily.

This last circumstance was particularly discouraging, since Sherman had noticed high-water marks on trees "ten feet above our heads". It was time to quit. He loaded his men up on the transports and went back down the Yazoo. Porter invited Sherman on board his flagship. Sherman came there, wet and depressed, stating: "I've lost 1,700 men, and those infernal reporters will publish all over the country their ridiculous stories of Sherman being whipped."

Porter was unconcerned: "Tcha! That's nothing; simply an episode of the war. You'll lose 17,000 before the war is over, and think nothing of it. We'll have Vicksburg yet, before we die. Steward! Bring some punch!" This good-natured, callous, and completely sensible remark helped calm the exciteable Sherman down enough for Porter to give him more bad news: McClernand was on a ship anchored at the mouth of the Yazoo and waiting to see him.

McClernand was there to finally assert command -- very much to Sherman's disgust and complaint. McClernand also relayed the news of Grant's withdrawal; Sherman concluded that it was probably a good thing that their expedition up the Yazoo had failed, thinking that "we might have found ourselves in a worse trap, when General Pemberton was at full liberty to turn his whole force against us." On 3 January 1863, the fleet steamed back up the Mississippi to Milliken's Bend, where Sherman formally handed over command to McClernand the next day. Sherman wrote his wife: "Well, we have been to Vicksburg, and it was too much for us and we have backed out."

Confederate papers began to speak of Vicksburg as the "Gibraltar of the West". Pemberton confidently wired Richmond:

VICKSBURG IS DAILY GROWING STRONGER. WE INTEND TO HOLD IT.BACK_TO_TOP

* While Sherman was floundering on the Yazoo, Grant was having frustrations of his own. There had been one bright spot on 21 December, when Van Dorn and his men, riding north from the ruin they had left at Holly Springs, moved on a small Union outpost just south of the Tennessee border at a place named Davis Mill. There were fewer than 300 Yankees there, under the command of a Colonel W.H. Morgan, assigned to protect a vital railroad trestle over the Wolf River. Although Van Dorn outnumbered the Federals over ten to one, Colonel Morgan was no pushover. He had his men fortify an old sawmill with railroad ties and bales of cotton, and built a nearby Indian mound into a moated earthwork. Both strongpoints were well sited, giving clear and supporting fields of fire on the railroad approaches.

Around noon that day, Van Dorn's men attacked the small band of Federals, but were quickly driven off. After two hours of exchanging pot-shots with the Union men, with the fire too intense to allow the rebels to even get close to the trestle much less torch it, Van Dorn sent a courier under a flag of truce over to the Yankee defenses to demand their surrender. Morgan, unimpressed by Confederate efforts to that time, gave them a polite NO. Their bluff called, the rebels withdrew, leaving behind about 70 casualties. Colonel Morgan lost three men.

Van Dorn was not greatly discouraged by this small defeat; his men had done plenty of damage to the rail line, and failing to destroy the trestle was not a major omission. The raiders moved north across the Tennessee line, continuing their destruction of the rail system and any other resources useful to the Federals, then ran back south of the border on 23 December. On the 25th, they made contact with a Federal column but escaped largely unharmed, and on the 28th they were back in Grenada. The raid had been a pleasant and profitable adventure, with Van Dorn's reputation among the Mississippians soaring in consequence.

* To the north, Bedford Forrest was having an adventure of his own. After resting in Union City on Christmas Day, he paroled his prisoners, most of them reporting back to their own commands with interesting "intelligence" they'd overheard from their guards. Of course, the conversations had been theatrics orchestrated by Forrest to give the Yankees the idea that Braxton Bragg's army was close in the tracks of the raiders. Forrest and his men then departed southeast, tearing up more track and causing trouble.

By 28 December, Forrest's work was more or less complete. Now the problem was to get away from the Union forces that were assembling around him. Characteristically, Forrest devised his escape plan in terms of attack. He decided to move into the center of the converging Federal columns, hit them as opportunity presented -- and then run, leaving the enemy in chaos and confusion. While ice-cold rain pelted the men in their saddles, they turned south instead of east.

Forrest's fearsome reputation, which he did everything to encourage, helped him a great deal. The Federal commander in Columbus, Kentucky, Brigadier General Thomas A. Davies, had been so alarmed by the presence of Forrest in Union City, only 10 miles (16 kilometers) away, and the wild stories provided by paroled Union soldiers of an invading rebel army, that he ordered the $13 million in supplies in Columbus loaded on steamboats so it could be removed. He also had his garrisons in New Madrid and Island Number Ten spike their guns and throw their powder in the river.

Similarly, 250 miles (400 kilometers) downstream from Columbus in Memphis, rumors that Forrest and his men were coming to liberate the city from the Federals put the pro-Confederate citizenry in such a state of excitement that the Union commander of the garrison there, Major General Stephen A. Hurlbut, was forced to site artillery at strategic locations in the city to maintain control.

Grant feared Forrest, but was not buffaloed by him. Grant was closely monitoring and encouraging the movement of three Federal columns, one from Corinth, one from Fort Henry, and one consisting of General Jeremiah Sullivan and two of his brigades, who had managed to pick up Forrest's trail. Sullivan wired Grant on 29 December:

I HAVE FORREST IN A TIGHT PLACE. MY TROOPS ARE MOVING ON HIM FROM THREE DIRECTIONS AND I HOPE WITH SUCCESS.

On 30 December, Forrest and his troopers paused and hid to discreetly watch Sullivan's lead brigade march by. The next day, 31 December, Forrest encountered Sullivan's other brigade blocking his way and, after sending four companies back to provide warning if the lead Federal brigade doubled back, began hammering away at the Federals with artillery about mid-morning. By about 1:00 PM, the rebels had captured three guns and 18 wagonloads of ammunition. White flags were showing along the Federal line; Forrest sent a messenger across to demand that the Union men surrender. Unfortunately, Sullivan's lead brigade then attacked him from the rear. As it turned out, the four companies Forrest had sent back for protection against such a possibility had gone up the wrong road.

It was unlike Forrest to be surprised, but it was totally unlike him to be panicked, and he sent his men forward and back in sharp attacks, stalling the Federals and allowing the raiders to escape. Legend has it that when one of his officers cried out to him in a dither: "What shall we do?! What shall we do?!" -- Forrest shouted back: "Break in half and charge both ways!"

Whatever the actual facts, the "Battle of Parker's Crossroads", as it was later memorialized, ended with Forrest's men giving the Yankees the slip -- though the raiders had to leave all the loot they had seized that morning, along with three guns of their own, no doubt much to the vexation of Forrest. 300 rebels were also taken prisoner; they had been fighting on foot, and their mounts had been scattered when the shooting began.

Sullivan was elated, reporting to Grant that "a good cavalry regiment" could easily go out and sweep up the disorganized rebels. Unfortunately, the Federals didn't have one on hand that was equal to Forrest's men, and the rebels got back to Clifton the next day, raised the sunken flatboats, and escaped across the Tennessee into safe territory.

Forrest had gone behind Federal lines less than three weeks before, leading men with poor weapons and little experience. When they returned, they had the best equipment the US Army could provide and had done the Federals $3 million in damage; inflicted casualties (including parolees) equal to their own number; kept ten times that many Yankees running in circles; captured or destroyed ten guns; and seized 10,000 rifles and a million rounds of ammunition. All that was incidental to their primary mission, which was thoroughly destroying Grant's rail communications from the town of Jackson up to the Kentucky border. They were now an elite. They would acquire a name along with their reputation: Forrest's Old Brigade.

* By that time, Grant's forces in Mississippi, their supplies destroyed and supply lines cut, were already backtracking to where they had come from. The Mississippians crowed at the retreating Yankees, until Grant decided to solve the problem of providing food for his men by simply robbing it from the locals. He sent out "all the wagons we had, under proper escort, to collect and bring in all supplies of forage and food" from the surrounding countryside. The good citizens of the state of Mississippi did not find this so amusing. In response to their protests, Grant responded with unarguable logic that "it could not be expected that men, with arms in their hands, would starve in the midst of plenty."

"Plenty" is what it was. Grant had expected to obtain only the barest subsistence by this tactic, but the wagons returned full of good things to eat. His soldiers had plenty of experience in quietly obtaining food that happened to be nearby, and with the blessing of the high command, they didn't even need to be quiet about it. They were only supposed to forage for food, but the foraging was accompanied by widespread looting and torchings that left the Mississippians less inclined to crow about the misfortunes of the Federals. Besides his aggressiveness, Grant had another great virtue as a leader. He learned from his experience, in this case finding out that "we could have subsisted off the country for two months instead of two weeks." He pocketed the lesson for future use.

BACK_TO_TOP