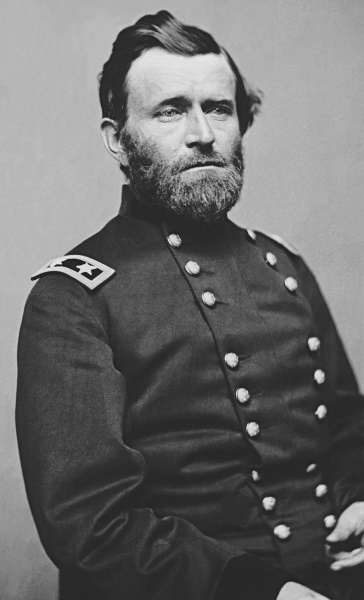

* In the summer of 1862, Union forces in the Mississippi River region were largely idle, with dispersed components scattered around the central Federal base at Corinth, Mississippi. The Union objective was to control the Mississippi, and to do that demanded the capture of Vicksburg, Mississippi, the Confederate strongpoint dominating the river. Major General Henry Halleck, the commander of those forces, was not eager to take action -- though his subordinate, the aggressive Major General Ulysses Grant, chafed at the inactivity.

US Navy Flag Officer David Farragut was more determined than Halleck, taking his fleet upriver from New Orleans to Vicksburg -- only to find that his ship's guns were unable to effectively bombard the city, which sat on high bluffs. He went back to New Orleans to load up more troops and returned to Vicksburg, but had no better luck; taking the city was beyond his means. After a Confederate ironclad, the ARKANSAS, inflicted serious damage on his fleet, Farragut went downriver and stayed there.

Inconclusive battles followed. In early August 1862, a Confederate force attacked the Union garrison at Baton Rouge, Louisiana; the rebels were driven off, but the Federals abandoned the city anyway. In mid-September 1862, a Confederate force attacked Grant's troops in the town of Iuka, in northern Mississippi. The assault failed, but the Confederates were able to escape capture.

* The outbreak of war between North and South in 1861 created two major fronts of action between the two sides: one in the East, focused in Virginia, and one in the West, focused on the Mississippi River. The primary goal of the Union in the West was to seize control of the Mississippi -- which would cut the Confederacy in half, and deprive the South of use of the river for communications and supply.

The Union drive got off to a good start in February 1862, when the Union Army of the Tennessee, under Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant, captured Forts Henry and Donelson, on the Kentucky-Tennessee border. That unhinged Confederate positions in Kentucky, leading to their withdrawal; Nashville, Tennessee, was bloodlessly occupied by Union forces on 25 February. The surrender of the two forts greatly encouraged the North, with Grant promoted to major general of volunteers.

The capture of the two forts led to a supremely violent collision between Grant's forces and those of Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston on 6 & 7 April 1862, in the vicinity of Shiloh Church in Tennessee; the bloodletting exceeded that of all other battles in American history to that time. General Johnston was among the dead, being replaced by his second-in-command, General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard.

While the Confederate force had to withdraw, the great numbers of killed and wounded raised a huge outcry in the North and put Grant under a cloud -- with the theater commander, Major General Henry W. Halleck, taking effective command of Grant's force and sidelining him. However, Union morale was boosted in late April when a US Navy force under Flag Officer David Glasgow Farragut captured New Orleans. The fall of New Orleans cut the Confederacy's river communications off from the open sea, and proved as discouraging to the South as it had been encouraging to the North.

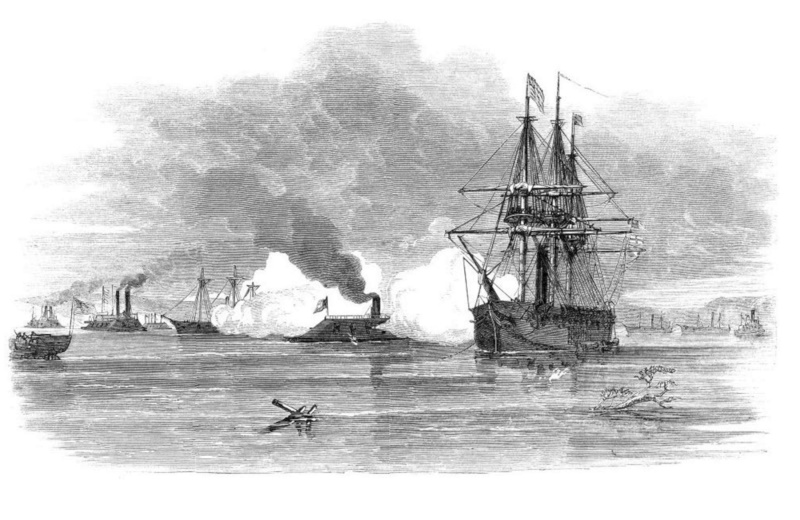

At the end of May, Halleck captured Corinth, Mississippi, the main Confederate base in the upper Mississippi region. It was hardly any great victory; Halleck, a timid general, moved so slowly that Beauregard was able to withdraw all of his force and most of his materiel unmolested. Nonetheless, the Confederate defense of the region had become unhinged; on 6 June, a force of Union river ironclads and other warships -- under the overall command of Navy Flag Officer Charles Henry Davis -- defeated a scratch Confederate fleet at Memphis. The city was then occupied by the Federals. The Confederacy had lost control of eastern and central Tennessee.

* The fall of Memphis left Halleck in a very good position to strike against a weaker and demoralized enemy at will. Unfortunately, with Halleck in charge, "will" was not much in evidence. Morale faltered in the ranks. Corinth was no prize in itself: there was little water there, a summer drought set in not long after the Federals arrived and made matters that much worse, and such water as was to be had was full of dirt and disease. Flies and mosquitoes were thick, while Northerners became acquainted with an unfamiliar bloodsucking parasite, the tiny chigger mite, that was even nastier. As a Wisconsin man put it, the chigger's mission was "to eat and die; every soldier was a walking chigger cemetery."

There was demoralization at the top as well. Halleck was not an easy man to work for, lacking in energy and focus, inclined to the petty and disagreeable. Major General William Tecumseh Sherman -- Grant's close colleague and good friend -- was talking with General Halleck, and Halleck mentioned that Grant had applied for a month's leave, to depart in the morning. Sherman suspected something was up. He went over to Grant's tent, where he found Grant forlornly bundling up some letters. Grant confirmed that he was leaving. When Sherman asked him why, Grant replied: "Sherman, you know. You know I am in the way here. I have stood it as long as I can, and can endure it no longer."

Sherman asked: "Where are you going?"

"Saint Louis."

"Do you have any business there?"

"Not a bit." Sherman didn't accept that reply casually. He pointed out that a year before -- when he had suffered a fit of nervous exhaustion, and had been temporarily relieved of duty -- the papers had called him "crazy as a loon" and now he was in "high feather". He told Grant that if he departed, "events would go right along, and he would be left out; whereas, if he remained, some happy accident would restore him to his true place." The game wasn't over yet, not by a long shot, and if he left he would simply deal himself out of it. Grant gave it some thought. He said he would consider the matter, and not leave without getting in touch with Sherman. A week later, Grant told Sherman he would stay.

* Halleck had overall control of an army of 120,000 men, enough to roll over any opposition the Confederates had in the region, but on 9 June he began to methodically dismember his own force. That was not without some good reason: he had to hold down a large territory where the locals weren't always very enthusiastic about the Union cause, and besides, if all of his soldiers remained holed up in unhealthy Corinth through the summer, a good number of them would be struck down by disease.

Halleck ordered four divisions under Major General Don Carlos Buell to march east, to hook up with forces under Major General Ormsby Mitchel. The combined force would then drive on Chattanooga, Tennessee -- from where it could advance on Knoxville, Kentucky, or due south to Atlanta, Georgia. That was the only fighting Halleck planned for the moment.

Sherman was sent west to Memphis with two divisions to repair railroads and generally attempt to restore normalcy to the lives of the population. Major General John McClernand -- an Illinois politician in uniform, not much respected by the regular Army generals who dealt with him -- was also sent off with two divisions to Jackson, Tennessee, with the same mission. Halleck stayed in Corinth with the remainder of his force, where he provided direction for the other three parts.

One of the consequences of this shuffling was that Grant was put back in charge of what had been his old Army of the Tennessee, which gave him control over Sherman's and McClernand's commands. Grant received permission to set up his command in Memphis with Sherman, and rode off on 21 June with an escort of a dozen cavalrymen. Confederate raiders got wind of Grant's travel plans, but were too slow and failed to capture him.

Grant arrived in Memphis on 24 June and found things "in rather bad order, secessionists governing much in their own way." He asked Halleck for more troops, but Grant was still on a short leash. Despite the command rearrangement, he was only slightly in a better position than he had been before the change, and the result of the request was another session of bickering with Halleck that went on for several weeks. The next month, Halleck would be called to Washington DC to become the general-in-chief of all the Union armies; from there, Halleck would continue to exert long-distance control over Grant.

BACK_TO_TOP* Downriver, following the surrender of New Orleans in April, Flag Officer Farragut spent almost two weeks refitting and resupplying his vessels, which had suffered damage in the fight for the city, and then proceeded up the Mississippi. His fleet included 1,400 troops, from the command of Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler, a Massachusetts politician in uniform, now the effective military dictator of New Orleans. It was a hell of a trip. All Farragut had were his deep-draft screw warships -- excellent for fighting on the open ocean but poorly suited to river warfare, which required flat-bottomed paddle-wheeled craft. His ships ran aground often; their sails were of no use on the river, and keeping the big vessels fueled was laborious; and the 1,400 troops brought along came down with malaria and dysentery.

The ships still carried a lot of guns, and the Confederates could offer little resistance. Baton Rouge, the Louisiana state capital, surrendered quietly on 12 May 1862, the state government having fled inland to the town of Opelousas the week before. Natchez, Mississippi, fell a few days later. A Louisiana woman wrote in her diary, reflecting the naive ideas of warfare popular in the early days of the conflict: "This is a most cowardly struggle, These people can do nothing without gunboats ... These passive instruments do their fighting for them. It is at best a dastardly way to fight."

The ultimate target of Farragut's drive was Vicksburg, Mississippi, the center of trans-Mississippi commerce of the Confederacy, a rail hub to the east fed by the Red, Arkansas, and White rivers from the west. Union President Abraham Lincoln regarded its capture as more important than that of New Orleans, having told Flag Officer David Dixon Porter -- Farragut was his adoptive brother -- during a White House visit earlier in the 1862: "We may take all the northern ports of the Confederacy, and they can still defy us from Vicksburg. It means hog and hominy without limit, fresh troops from all the states of the Far South, and a cotton country where they can raise the staple without interference."

Farragut's assumption had been that Vicksburg would be unguarded and would fall as easily as Baton Rouge and Natchez; but the fall of New Orleans had alerted the rebels to the importance of Vicksburg, and small detachments of troops and artillery began to arrive there, starting on 1 May. On 18 May, one of Farragut's ships, the sloop ONEIDA, arrived at Vicksburg, and the ship's captain, Commander Samuel Phillips Lee, sent the Confederates an ultimatum ordering them to surrender the city. Five hours later Lee got a response from the city's military governor, Colonel James L. Autrey: "Mississippians don't know, and refuse to learn, how to surrender to an enemy. If Commodore Farragut or ... General Butler can teach them, let them come and try."

Autrey had called Lee's bluff. The guns of Farragut's ships could not be elevated high enough to be effective against the rebel fortifications being built along the high ground of the town, and there were enough Confederate troops in the city to easily repel the soldiers Farragut had with him. More rebel troops were rumored to be on the way. Farragut concluded there was nothing else to be done for the moment. He went back downstream to New Orleans, leaving garrison forces at Natchez and Baton Rouge. Natchez had been re-occupied for a short time by the Confederates in the interim; the unlucky citizen of that town who had carried Farragut's demand to surrender to the mayor was jailed for treason and almost executed. General Beauregard had to personally intervene to save the poor fellow's life. It appeared Vicksburg was going to be a problem for the Federals.

* After Farragut returned to New Orleans, he was flooded with angry telegrams from Washington, complaining about his failure to attack Vicksburg. When he heard the news, Assistant Navy Secretary Gustavus Fox cried out: "Impossible!" -- and immediately dispatched an order in triplicate on three different ships, instructing Farragut to go back upriver immediately. Two days later, Fox sent an even more emphatic message:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

The President requires you to use your utmost exertions (without a moment's delay and before any other naval operations are permitted to interfere) to open the Mississippi and effect a junction with Flag Officer Davis.

END_QUOTE

On 6 June, the day of the Confederate defeat at Memphis, Farragut started back upriver. The fleet arrived on 25 June. Flag Officer Davis's river fleet was not far north on the river from Vicksburg, with Davis standing by to see what he could do to help.

This time, Farragut had more soldiers, a total of 3,200 -- and brought along mortar schooners, which could reach Vicksburg's defenses. They pounded the city for two days, and then on the 28th, Farragut decided to run upriver past the guns of Vicksburg. Eleven warships started out at 2:00 AM, and opened fire on the city in the darkness, while the Confederate batteries returned the fire.

It was not particularly effective fire in either direction. Although Farragut's flagship, the HARTFORD, scored a few hits on the batteries, most of the Union fire fell short. Similarly, the rebels scored few hits on the Federal warships. Only three of the vessels had to turn back, and Farragut suffered only 15 dead and 30 wounded. For the citizens of Vicksburg, however, the bombardment was terrifying. A Confederate officer wrote: "The roar of the cannon was continuous and deafening. Loud explosions shook the city to its foundations; shot and shell went hissing through the trees and walls, scattering fragments far and wide in their terrific flight; men, women, and children rushed into the streets, and amid the crash of falling houses commenced their hasty flight to the country for safety." A woman was killed by a shell fragment.

All the violence and terror were for nothing. Farragut concluded that his run past the city had served no purpose, and wrote Navy Secretary Gideon Welles that it would take 12,000 or 15,000 men to take Vicksburg. With 10,000 rebels defending the city, there was little Farragut could do with the 3,200 men he had with him. For lack of anything better to do, the men's commander, Army Brigadier General Thomas Williams, put his men ashore on the Louisiana side of the river, setting them to work digging a canal across a hairpin turn to divert the Mississippi away from Vicksburg.

The canal proved to be miserable work, one problem being a lack of manpower. Williams attempted to address that issue by seizing local slaves, and enslaving them in turn; they were treated so badly that even local slave-owners were appalled. The morale of his troops was not improved by the fact that Williams was a rigid disciplinarian, insisting on strict inspections under difficult field conditions. In the meantime, Farragut's fleet was idle upriver of Vicksburg, presenting a good target for an attack, if the Confederates could find the means.

BACK_TO_TOP* 45-year-old Lieutenant Isaac Newton Brown of the Confederate States Navy was eager to attack Farragut's ships. Brown had been ordered in late May to take command of the unfinished ironclad ARKANSAS, sitting docked at Greenwood up the Yazoo River -- which flowed into the Mississippi from the west, just north of Vicksburg -- where she had been towed before the fall of Memphis. He was to complete construction of the vessel, and then take her to war. What he found was a "mere hull", with engines in pieces, and guns without carriages. A scow carrying a load of railroad iron to be used for armor was lying sunk nearby.

Brown had good reason to be discouraged, but he lit into the job with a whirlwind of energy. He raised the scow to get the iron, had the ARKANSAS towed downstream to Yazoo City where there were better facilities, and commandeered every resource he could get his hands on to get the ship ready for battle. He powered machinery with the hoisting engine of a handy steamship, and brought in rural blacksmiths to work the iron, while 200 carpenters worked on the vessel itself. The carriages for the ten guns were a problem, since nothing like them had ever been built in Mississippi -- but they were provided on contract from "two gentlemen of Jackson" who ran a wagon factory.

The ARKANSAS was as ready as she could be by 12 July. Brown spent two days organizing a crew, including men from the wooden rams that had been lost at Memphis and volunteers from the infantry, and on 14 July they went down the Yazoo to pay a social call on the US Navy. The ironclad made good progress that day, getting close enough to the Federal fleet to hear the Yankees engaged in gunnery practice -- but then it was discovered that steam had got into the powder in the forward magazine. Brown tied up at a sawmill, had his men spread the powder on tarps in the sun, and by constant shaking and turning they managed to get it dry by the time the sun went down. They packed what they could into the aft magazine and continued on their way. Brown had reports of 37 enemy warships in front of Vicksburg. He wanted to hit them at dawn.

The night's journey did not go smoothly. The vessel's two engines had a tendency to seize, one at a time, and throw the ship into the bank. This happened before dawn, and the crew had to work hard to get her afloat again. While they were working at this, one of the lieutenants went ashore to get information from a nearby plantation. All he found there, however, was an old slave woman who, being loyal to her masters, wouldn't tell him anyone had even been there. He was annoyed: "They have but just left. The beds are yet warm."

"Don't know about that. And if I did, I wouldn't tell you."

"Do you take me for a Yankee? Don't you see I wear a gray coat?"

"Certainly you's a Yankee. Our folks ain't got none of them gunboats."

It took an hour to refloat the ironclad. The sun was up by the time she entered Old River, a ten mile (16 kilometer) long spur of the Mississippi. Lookouts spotted three ships ahead: the Union ironclad CARONDELET, ironically commanded by Henry Walke, a friend and messmate of Brown's from the old Navy, and the wooden gunboats TYLER and QUEEN OF THE WEST, which had been sent upriver to investigate reports that the Confederates were building a warship on the Yazoo. They were about to receive convincing confirmation.

Brown ordered the men to battle stations. He stood exposed, directly over the bow guns, as the ARKANSAS steamed forward while the gunners, stripped to the waist, stood at their pieces. The Federals were startled by the sudden appearance of the Confederate monster. The QUEEN OF THE WEST -- which was built for ramming attacks, and otherwise unarmed -- prudently turned and ran, while the CARONDELET and the TYLER stayed on course, intending to fire their bow guns, then turn downstream and fight with their stern guns. Their captains hoped the sound of cannon fire would alert the fleet downstream.

The two Yankee vessels fired at the rebel ironclad, missed, and turned around to escape, but the ARKANSAS was too fast. She closed on the CARONDELET and began to fire shells into the gunboat's exposed stern, damaging the ship severely. The CARONDELET's return fire glanced off the ARKANSAS' prow, doing no damage except to a seaman who stuck his head out of a gunport to see what was going on -- and had it immediately blown off. A lieutenant ordered one of the sailors to throw the body overboard to keep it from demoralizing the other men, but the fellow replied: "Oh, I can't do it, sir! It's my brother!"

Brown, who was still exposed above the ship's bow, was wounded himself a moment later. He felt a blow to his head and thought himself killed, until he took a handful of clotted blood from the wound and saw no bits of brain mixed in. Reassured, he remained at his post to direct the fight, but the TYLER had intervened to protect the CARONDELET, and Federal riflemen peppered the ARKANSAS. Brown was wounded again in the head, this time with a bullet. He was taken below decks to lie with the dead and wounded. When he came to, he got up and went back topside again.

As the three ships approached the Mississippi, Brown closed on the CARONDELET to ram her and finish her off, but the Federal ironclad ran into the bank, taking itself out of the fight. Brown directed his fury towards the TYLER, which was steaming as fast as she could down the Mississippi. The sailors on board the Union fleet downriver had indeed heard the firing, but they simply thought their comrades were shelling snipers. As the wooden gunboat approached with the ARKANSAS behind her, one officer said: "There comes the TYLER with a prize."

Every vessel of the fleet had its steam down and no guns were loaded. Suddenly the ARKANSAS was among them, a "forest of masts and smokestacks", as Brown put it. The ARKANSAS began to hammer the Yankee ships, with the gunners, as Brown put it, "firing rapidly to every point of the circumference, without the fear of hitting a friend or missing an enemy". Despite the surprise the Federal sailors reacted swiftly, Brown later saying: "I had the most lively realization of having steamed into a real volcano."

Shot smashed through her armor twice, laying out gun crews, while her smokestack was riddled, reducing her boiler pressure. The engine room became a sweltering oven and the black gang had to be relieved every 15 minutes. Brown said: "The shock of the missiles striking our sides was literally continuous." Despite this punishment, the ARKANSAS continued the fight, moving downstream through the anchored warships. When a Union steam ram tried to block the ship's exit, Brown ordered it rammed in turn; the ARKANSAS then slammed a shell into the wooden ship's boiler, resulting in a satisfactory explosion of steam. The rebel ironclad cruised out of the battle unpursued.

When the ARKANSAS approached Vicksburg, a crowd assembled on a bluff to greet her with cheers and tossing of hats, but when the ironclad came closer they fell silent. The vessel looked like a floating slaughterhouse. She had taken a severe beating in her passage through the Yankee ships, and 30 of her men were dead or wounded. The Federals had taken about 60 casualties; one vessel was disabled, and almost all of them had been hit, many by their own crossfire.

* Farragut had been sleeping late that morning; when the shooting started, he had gone above decks to watch the battle in his nightshirt, in very bad humor. When it was over, he went back down below decks, muttering angrily: "Damnable neglect, or worse, somewhere!" When he came back up in uniform, he was even madder. He had made up his mind to immediately run the fleet past Vicksburg in broad daylight and blast the upstart ARKANSAS to fragments, but his staff managed to beg him for a little delay: at least they should have time to wash the blood off the decks.

Farragut still ordered his ships to make the run at sunset. Not only was he still angry, he was worried that the Confederate ironclad might go downstream and destroy some of his vessels that were downstream, not having made the run with the rest of his fleet. He ordered all the guns to be loaded with solid shot, and even had the heaviest anchor he could find hung from a yardarm so that it could be dropped on the ARKANSAS to punch through her decks. Davis's ships were to remain behind and give covering fire.

The ships went by single-file, but in the twilight the ARKANSAS was almost invisible except for the flash of her guns -- and the Confederates, sensibly predicting that the Federals would retaliate, had moved the ironclad after sundown. The firing was confused, with neither side scoring many hits, except for the HARTFORD, which slammed an 11-inch (28-centimeter) shot through the rebel vessel's armor. Farragut made the passage south with about two dozen casualties, less than he suffered going north.

He was still determined to destroy the ARKANSAS. In the morning he sent a message to ask Davis to join in a combined daylight attack, but Davis refused. Farragut kept at him, and on 21 July Davis agreed to send the ironclad ESSEX downstream with the steam ram QUEEN OF THE WEST. The ESSEX was commanded by Commander William Porter, brother of Flag Officer David Dixon Porter. The idea was that the gunboat could pin down the ARKANSAS, while the ram sent her to the bottom.

It didn't work. Lieutenant Brown swung his ship out in the river to present her prow to her attackers. The ram struck only a glancing blow, while the ARKANSAS and the ESSEX hammered at each other at point-blank range. Porter said later: "We could distinctly hear the groans of her wounded." Then the Vicksburg shore batteries got into the fight and the two Yankee vessels had to quit and go back upstream. The ESSEX had been hit 42 times and the QUEEN OF THE WEST had been riddled, but neither ship suffered serious casualties or damage. The ARKANSAS lost about a dozen men.

Navy Secretary Welles later wrote that the sortie of the CSS ARKANSAS was "the most disreputable naval affair of the war." There was nothing more to be done; Farragut felt he'd had enough. Fuel was a problem, the sick list was long and getting longer in the Mississippi heat, and the river was falling so much that he worried about being stranded. A letter from Welles, written before the ARKANSAS had made its appearance, arrived to instruct Farragut to "go down the river at discretion." Farragut judged it discreet to do so immediately. He loaded up General Thomas Williams and his men, their canal incomplete, and took them downriver to Baton Rouge, along with the ESSEX and two wooden gunboats.

Before leaving, Williams conscientiously handed such slaves as had survived their forced service to him back to their masters -- though some managed to escape and seek their freedom. Farragut then proceeded to New Orleans to refit his ships for blockade duty along the Gulf Coast. Davis left the same day, to take his ironclads to support Federal operations in Arkansas.

BACK_TO_TOP* Farragut's Vicksburg expedition had been a bust, undone primarily by General Halleck's indifference. Farragut had written Halleck for help, and got nothing but equivocation in reply. Without a substantial ground force, there was no way to take Vicksburg. In compensation, when Farragut arrived in New Orleans, he found out that he had been promoted to the rank of rear admiral. Congress had promoted a batch of 13 naval officers to that rank; there had never been any admirals in the US Navy before that time.

The Confederates were elated: a home-built ironclad had taken on a huge Federal fleet, bloodied it, and seemingly had single-handedly lifted the river siege of Vicksburg -- though Farragut would have likely left in any case. A bold stroke against a superior enemy seemed to make all the difference, and with other bold strokes elsewhere the future for the Confederacy was beginning to appear much brighter than it had been only a month or two earlier. In fact, after the departure of Federal naval forces from Vicksburg, the Confederates felt encouraged enough to take the offensive against the Federal ground forces sitting passively at their garrisons throughout the south.

Confederate forces in the region were organized in two components:

Van Dorn had been the commander in Arkansas, with Price as one of his lieutenants. Van Dorn's army had been defeated by Union forces at Pea Ridge in early March, with Van Dorn leading the survivors, badly depleted by desertions, across the Mississippi after Shiloh to reinforce Confederate forces there.

Van Dorn was an energetic man, inclined to glorious schemes; he had considered leading his army north to capture Saint Louis, but was convinced by the success of the ARKANSAS to drive south towards New Orleans instead. Regaining control of that city would be a powerful boost to Confederate morale, just as its fall had led to discouragement.

On Sunday, 27 July, the day after the Union flotilla left Vicksburg, Van Dorn ordered Major General John C. Breckinridge to recapture Baton Rouge from Union Brigadier General Thomas Williams and his men. Breckinridge had 4,000 soldiers -- but by the 30th of July, that total had been reduced to 3,400 by illness, and he had learned the Yankees had 5,000 men in Baton Rouge, as well as the support of gunboats.

He wired Van Dorn of these obstacles, but said he would go ahead with the attack if the ironclad ARKANSAS could deal with the gunboats. The vessel was immediately sent downstream to provide support. It was scheduled to arrive on 5 August. Isaac Newton Brown was not in command, due to illness and other distractions, the acting captain being Lieutenant Henry Stevens.

The rebels were miserably equipped, and over the next week more of them fell ill. By Tuesday, 5 August 1862, Breckinridge was down to about 2,600 men, but they went ahead and attacked the Federals through a dense fog that morning. The Federals were better equipped and had more men, but about half of them were on the sick list as well. Breckinridge's troops made good progress at first, throwing back the Federal defense. When Thomas Williams realized that most of the officers on his flank had been shot or dispersed, he rode into the fighting, shouting: "Boys, your officers are all gone! I will lead you!" A few minutes later, a bullet struck him in the chest, knocking him off his horse and killing him.

Williams' death might have been the breaking point for the Yankees -- but then the battle began to shift back in their favor. The ARKANSAS' engines had broken down, and the ironclad was aground, within earshot, but out of range of the fighting. Federal gunboats were free to pound the rebels with heavy shot and shell, with the bombardment beginning to tell against the Confederates. By midmorning, the rebels had been driven back and had to abandon the field to the Yankees. The Federals had lost almost 400 men, the Confederates over 450. Among the rebel dead was Lieutenant A.H. Todd, one of President Lincoln's brothers-in-law.

The crew of the ARKANSAS struggled with her balky engines all day and all night. The next morning the Union ironclad ESSEX came upstream to challenge her, and though the rebel ship went forth to meet the attack, her engines failed again and grounded her. Stevens ordered her burned; she exploded and sank in the Mississippi. The Confederates would never build another ironclad to trouble the Federals on the Big Muddy.

Despite the fact that the Federals had beaten the rebels at Baton Rouge, Breckinridge felt proud of the fact that his raggedy, poorly fed, sadly equipped, and wretchedly sick soldiers put up such a good fight against a much better-equipped enemy. In fact, two weeks later they were able to claim, with some good cause, that they had not actually lost after all. Ben Butler decided to consolidate his forces and abandoned the city, the troops pulling out to New Orleans.

A few months earlier, it had seemed that the Confederacy would be shortly cut in half down the Mississippi. Now, with a few bold blows, their soldiers and sailors had restored a good stretch of the river to Confederate control. Breckinridge sent most of his men to Port Hudson, north of Baton Rouge, where they would fortify its bluff, in hopes of creating another Vicksburg. If the Federals wanted to come back, they'd have their work cut out for them.

BACK_TO_TOP* While Flag Officer Farragut was scratching at the defenses of Vicksburg in early July, General Grant was under fire from his superior officer, General Halleck. On the 11th, Halleck ordered him to report to Corinth from Memphis. It took Grant three days to get there -- and then, somewhat to his relief, he found that instead of being raked over the coals on some pretext he had been, as the senior general in the region, more or less restored to his earlier authority. Specifically, he was in command of his own army, with elements under Sherman at Memphis and McClernand at Jackson, Tennessee; divisions under Brigadier General William S. Rosecrans, arrayed around Iuka, Mississippi; and a number of other units scattered around the department.

It was not an entirely satisfactory situation. The problem wasn't a lack of manpower: even after detaching a division for operations in Arkansas, Grant had 75,000 men left. The problem was that those men were, for the moment, very vulnerable. The summer had been hot and dry, and the Tennessee River had dried up to the point where it could not be used for supply. There were few rail lines; most of them had been torn up, while those that were not were only too easily cut by guerrillas and Confederate cavalry raiders. Earl Van Dorn's mobile force at Holly Springs represented a distinct threat. Although Van Dorn had managed to assemble only about 35,000 men, less than half of Grant's, he was not at the end of a long supply line, and could strike at will at any of Grant's separated forces.

Furthermore, Grant was perfectly aware that he had obtained his command by default, just because no one else was available to take the job. Grant later wrote: "I became a department commander because no one was assigned to that position over me." Authority granted on such a tenuous basis could easily be withdrawn.

Grant could only bide his time, remaining uncomfortably on the defensive. He sensibly made sure that he was in touch with his field commanders, and that his men were dug in, to deal with Confederate attacks. Despite Grant's preparations for trouble, he still described the time later as "the most anxious period of the war."

* The two Confederate forces arrayed against Grant, under Earl Van Dorn and Sterling Price, were having command difficulties at the time. Price had orders to harass the Yankees, and had called on Van Dorn for help. As usual, however, Van Dorn was full of grand plans, once more seeking a drive on Saint Louis or other targets in the upper Mississippi Valley; He suggested instead that Price assist him instead. Not surprisingly, communications between the two men fell apart, and Van Dorn decided to pull rank, or at least seniority, calling on the Confederate Secretary of War to back him up. Confederate President Jefferson Davis personally wired Van Dorn to inform him that he was in charge.

Price was not available to be informed, since he was on the march from Tupelo towards Iuka. On 14 September, the Union garrison in the town, under the command of a Colonel Robert Murphy, fled without destroying the stocks of hardtack and salt pork, and leaving behind a small fortune in bales of confiscated cotton. The conflict had, of course, interfered with the supply of cotton to the North, and so it had become a valuable prize of war for Union forces. Price moved in, unopposed, seizing the stores and burning the cotton.

Price had hoped to move on to support an offensive into Kentucky being conducted by the Confederate Army of Tennessee -- led by Major General Braxton Bragg, the senior Confederate commander in the region between the Appalachians and the Mississippi -- but then events sidetracked his plans. First, Price found out his intelligence was faulty. Grant had relocated some of his forces that his been around Iuka, but Price found out that Rosecrans was still nearby with two divisions. Second, while Price was weighing his options, a courier arrived to inform him that Van Dorn was now in charge. Price decided to stay in Iuka and wait to see what Van Dorn wanted him to do.

One of Grant's great virtues was that he saw opportunities, where others saw threats. He later wrote: "It looked to me that, if Price would remain in Iuka until we could get there, his annihilation was inevitable." Grant moved against Price with four divisions, the two under Rosecrans and two under Major General Edward C. Ord that had been brought from Corinth, with a total of about 17,000 men. Since Price had about 15,000 men, Grant could not hope to overwhelm him with superior numbers, all the more so because a defender generally had the advantage. Grant decided to rely on strategy, sending Ord and his men to fall on Iuka from the north, while Rosecrans quietly swung around to attack from the south to take the rebels by surprise. It sounded nice on paper, and both Ord and Rosecrans were enthusiastic -- but armies tend to be blunt instruments and not always the tool for finesse. Rosecrans also warned that Price would be hard to trick, describing him as an "old woodpecker."

On 17 September, Ord moved out of Corinth to the town of Burnsville, about 12 miles (19 kilometers) down the rail line towards Iuka. There Grant made his headquarters and sent a message to Rosecrans, telling him to concentrate at Jacinto, eight miles (13 kilometers) south of Burnsville. The two columns would then move on Iuka, and attack at dawn on 19 September.

Rosecrans was delayed but Ord moved up on schedule, making tentative contact with Price's cavalry patrols around Iuka on the 18th. Since nothing more could be done until Rosecrans arrived, Ord then had to wait on Rosecrans. The recent great battle at Sharpsburg, Maryland, had ended in defeat for the Confederacy; Grant took advantage of the idle period to send a message to Price informing him of the defeat, to say that "this battle decides the war finally", and suggest that Price avoid "further useless bloodshed and lay down his arms." Price, unimpressed, politely replied that he would lay down his arms when the Confederacy won its independence from the United States.

Grant shrugged, and sent Ord forward on the 19 September 1862 -- telling him to move carefully, since Rosecrans apparently was still on the road. Ord's men advanced slowly, encountering little resistance; as the afternoon wore on, there was still no sign of Rosecrans, and so Grant ordered them to halt and wait for the sounds of battle before moving to attack. About 6:00 PM, Ord got a dispatch from the commander of his lead division written two hours previously, reporting "dense smoke" rising from Iuka and concluding that the enemy was withdrawing, burning their supplies as they pulled out. Ord moved forward again, just as cautiously, until night halted his men in place.

* Unknown to Grant and Ord, however, not only had Rosecrans arrived at the southern approaches to Iuka at about 2:30 PM that day, but a violent battle had followed. The fight was the cause of the smoke that had been reported to Ord. For some unfathomed reason, sounds of the fighting had not carried upwind.

Price had indeed been originally misdirected by Ord's movements, and had his men in place facing north, but on being told of Federal columns approaching from the south, he had ordered Brigadier General Henry Little to move south with two brigades, and confront the new threat; Price went along to see what was going on. Rosecrans' men were dispersed in an extended column that was hampered by forest; Little wasted absolutely no time in attacking the Federal advance units, overwhelming a Union battery of artillery, who stood to the last while taking severe casualties. The rebels seized nine guns, and things seemed to be going very well for them -- but then Little, conferring on horseback with Price, was struck in the forehead by a bullet and killed instantly. Rosecrans was able to bring his forces to bear and drive the Confederates back, only to be forced back himself once again by a stubborn rebel countercharge. Roughly 800 Federals and a little over 500 rebels fell in the fight.

Grant didn't know any of this until the following morning, when he got a message from Rosecrans outlining what had happened. It wasn't welcome news by any means, but Grant still thought he had Price where he wanted him. A little after 8:00 AM on the 20th, the Federals moved on Iuka in the pincher movement they had originally planned.

Nobody was there. All of Price's captured stores had been loaded on wagons, ready to move, even before the clash with Rosecrans, and Price had pulled out during the night over a road that Rosecrans had left unguarded. Rosecrans' judgement of Price had proven completely justified. Grant ordered Rosecrans to pursue the rebels, but his men ran into an ambush and Rosecrans gave it up. In the meantime, Ord was moving his men back to Corinth by rail, just in case Van Dorn intended to try something while the opportunity was available.

BACK_TO_TOP