* The confrontation between Union and Confederate forces at Gettysburg was unplanned. There was nothing strategic about the town; it was just where the two armies happened to meet. The battle began in the morning along the approaches to the northwest of the town, and quickly increased in violence. It then shifted to the hilly terrain at the north of the town, maintaining its fury. At the end of the day, both sides had lost many soldiers, with nothing in particular to show for it.

* As Buford had predicted, the rebels moved on Gettysburg when the sun came up on 1 July 1863. An Illinois cavalry regiment on picket duty along the Chambersburg Pike, which led into Gettysburg from the northwest, traded shots with rebels moving down the pike about three miles (five kilometers) out of town. The Union cavalry regiment saw they were facing Confederates in at least brigade strength, and decided to withdraw.

Neither side was particularly prepared to bring on a general engagement that morning. Lee's forces wouldn't link up for another day, and Meade had ordered his commanders to set up defensive positions about 20 miles (32 kilometers) south of Gettysburg. However, events were already beginning to acquire a momentum of their own.

The geography of Gettysburg would dictate the shape of the battle. The Chambersburg Pike went over three ridges on the way to Gettysburg: first Herr Ridge, then MacPherson Ridge, and finally Seminary Ridge, just to the west of the town. A stream named Willoughby Run flowed between Herr Ridge and MacPherson Ridge; the Lutheran Theological Seminary stood on top of Seminary Ridge just south of the pike. An unfinished railroad line ran parallel to the Chambersburg Pike to the north.

Confederate Major General Henry Heth -- he'd been promoted following the death of Stonewall Jackson -- got to the top of Herr Ridge at about 08:00 AM, and found Buford's cavalrymen competently deployed, facing him along the east side of Willoughby Run. Heth sent two brigades forward to drive out Buford's troopers. One brigade, under Brigadier General James J. Archer, moved parallel the south side of the pike, while the other, under Brigadier General Joseph R. Davis, a nephew of the Confederate president, moved along the north side of the pike. Buford had about 2,750 men to face almost three times that many rebels. He ordered a messenger to ride off and ask Major General John Reynolds for reinforcements.

The rebels knew they held the advantage in numbers and advanced confidently, expecting to sweep the Union cavalry off the field. However, north of the turnpike they ran into a hail of lead from Buford's horse artillery and his troopers firing their breech-loading carbines from behind a low stone wall: Buford's men were no pushovers. Buford said later of his troopers: "Their fire was perfectly terrific, causing the enemy to break."

The rebels regrouped and pressed their attack, and by about 09:00 AM the Federals were starting to yield ground. Buford was watching the fight from the tower of the Lutheran Theological Seminary when Reynolds arrived and asked: "What's the matter, John?" Buford replied: "The devil's to pay!" Reynolds had ridden ahead of most of his troops and told Buford that substantial reinforcements wouldn't arrive for a while; he asked Buford if he could hold out until then. Buford replied: "I reckon I can."

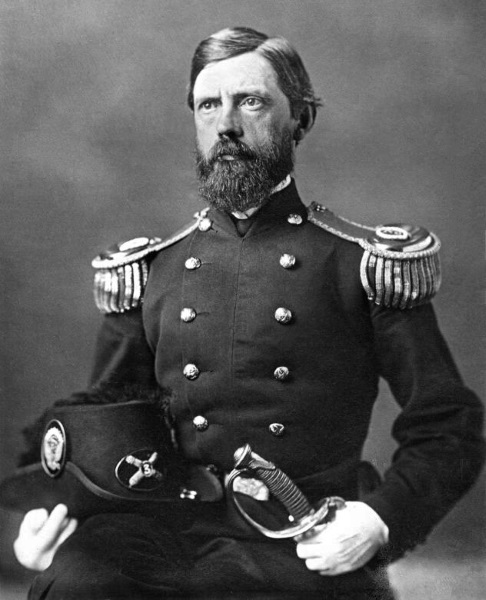

Reynolds then sent a messenger to Meade, telling the man to say: "The enemy is advancing in a strong force, and I fear they will get to the heights beyond the town before I can. I will fight them inch by inch, and if driven into the town I will barricade the streets and hold them back as long as possible." When the message was relayed to Meade, he said: "Good! That is just like Reynolds. He will hold out to the bitter end." Reynolds was a cool, highly professional West Pointer who was much admired in the Army of the Potomac, and the fact that he was a Pennsylvanian made him that much more determined to stop the rebels in their invasion of his home state.

Reynolds had ordered all of his I Corps to march to Gettysburg and had asked that III Corps and XI Corps follow up. The first element of I Corps, the two-brigade 1st Division under Brigadier General James A. Wadsworth, arrived first and went into the fight at about 10:00 AM, with the Federal soldiers dropping their knapsacks and loading up their muskets as they quick-stepped up MacPherson Ridge. Buford's hard-pressed cavalrymen were delighted to see the reinforcements moving into battle. The troopers called out: "We've got them now! Go in and give them hell!"

Reynolds rode into the thick of it to encourage his men, calling on them to push forward, and was then struck behind the ear by a bullet that killed him instantly. He was 42 years old. With the fury of the battle increasing, there was no time for Federal soldiers to register shock at Reynolds' death; they had other things to worry about.

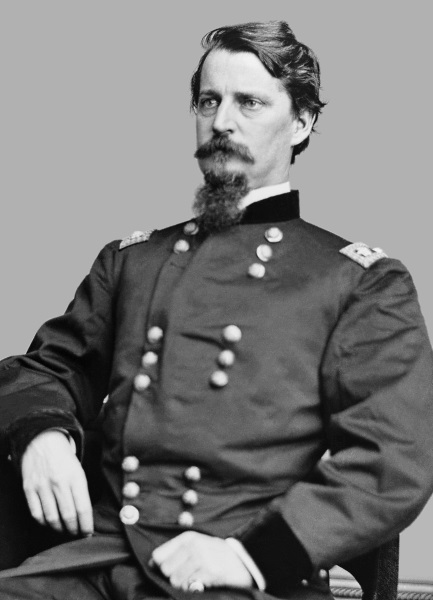

* Major General Abner Doubleday had been Reynolds' second-in-command. Doubleday had just arrived with the rest of I Corps, following Wadsworth's 1st Division. With Reynolds dead, Doubleday was now the senior Union officer on the field.

The 1st Brigade of the 1st Division had deployed across and south of the Chambersburg Pike, along with two of the five regiments of the 2nd Brigade. This 1st Brigade was the 1st Brigade, the legendary Iron Brigade or Black-Hat Brigade, with their trademark black felt slouch hats and a battle history underlined in blood. When Archer's advancing rebels saw who they were up against, they were startled. The Federals overheard the Confederates saying to each other: "There are those damned black-hatted fellers again!" "Tain't no militia! It's the Army of the Potomac!"

The Iron Brigade lived up to their reputation, meeting the rebel attack head-on and then flanking it from the south. The Confederates broke and ran, leaving behind dead, wounded, and prisoners. One of the prisoners was James Archer, who was roughly snatched up by a burly Irish private with the stereotypical name of Patrick Maloney, from a Wisconsin regiment. Archer was taken to Abner Doubleday. They had been friends in the old army, and Doubleday, forgetting circumstances, greeted him warmly: "Good morning, Archer! I am glad to see you!" Archer's reply was more than warm: "Well, I am NOT glad to see YOU by a damn sight!"

* To the right of the 1st Brigade's line, north of the railroad cut, the other three regiments of their brother 2nd Brigade held the line. However, the Union line was too short and a North Carolina regiment flanked the Yankees from the north, making their position impossible. Wadsworth reacted quickly, ordering the three regiments to fall back to Seminary Ridge. However, while two of the regiments pulled out immediately, the commanding officer of the third regiment had been hit before he could give the order to withdraw, and the regiment only fell back after taking severe casualties.

To the south of the railroad cut, the two regiments of the 2nd Brigade that had been fighting alongside the Black Hats -- the 14th Brooklyn and 95th New York -- realized the danger and faced north, established a line along the Chambersburg Pike, and started firing into the flank of the Confederate 2nd Mississippi, which was in pursuit of the other Federal regiments in retreat. The 14th Brooklyn and 95th New York were joined by a third regiment, the 6th Wisconsin, one of the 1st Brigade's regiments that had been held in reserve.

The rebel attack was broken up by this fire; the Confederates sought cover in the railroad cut. The Yankees were exposed to their fire, and Lieutenant Colonel Rufus Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin ran up to Major Edward Pye of the 95th New York, shouting: "We must charge!" Pye replied almost cheerfully: "Charge it is!" The three Federal regiments surged forward, taking severe casualties, but surrounding and trapping the 2nd Mississippi in the cut. The Federals had been badly bloodied in the charge and could have easily slaughtered the trapped rebels -- but the Yankees were somehow able to restrain their bloodlust, setting up a chant of: "THROW DOWN YOUR MUSKETS! THROW DOWN YOUR MUSKETS!" The Mississippians knew their position was hopeless and surrendered in mass. Colonel Dawes found himself burdened with an "awkward bundle" of surrendered swords. The Federals took about a thousand prisoners.

The surviving rebels had fallen back to Herr Ridge. It was about 11:00 AM, and the battlefield was now more or less quiet, except for occasional pot-shots taken by soldiers or cannoneers. The rebels had run into far more trouble than they had expected and taken the worst of the fight, but the day was still young, and they were not planning on giving up so easily. Both sides reshuffled and braced up their positions in preparation for executing or receiving an attack.

* Confederate General Heth planned to renew the assault, encouraged by messages from his corps commander, A.P. Hill, who was just up the Chambersburg Pike at the village of Cashtown. Hill was sick that day, but told Heth that reinforcements were on the way.

The Union commander on the field was now Major General Oliver Howard, who had arrived in Gettysburg at about 10:30 AM, in advance of his XI Corps. Since he was the ranking officer in the area, he took over from Doubleday.

Gettysburg was at the junction of nine roads, which defined the avenues of attack into the town, laid out roughly like the positions of a clock:

General Howard had observed the retreat of Wadsworth's regiments north of the railroad cut from the top of a building in Gettysburg and feared the worst. The worst didn't happen, but Howard knew that the rebels would come forward again in a very short time.

MacPherson Ridge and Seminary Ridge joined together in the north to form Oak Ridge, which terminated at a knob named Oak Hill north of the Mummasburg Road. Oak Hill overlooked Gettysburg from the northwest. At 12:30 PM, the rebels began a push in the area, setting up guns on Oak Hill and accurately bombarding the Federals below them. Large bodies of Confederates moved into position for attack. A brigade of Union reinforcements under Brigadier General Henry Baxter was moved up to hold the line, but it didn't seem to be enough to stop any serious assault.

However, Howard had been prudent and quick in the deployment of his XI corps. He placed one division under the command of Brigadier General Adolph von Steinwehr to the south of Gettysburg on a knob named Cemetery Hill to protect his flank, and von Steinwehr -- a Prussian Army officer in a previous life who looked the part -- professionally set his men to digging defenses in the cemetery on top of the hill.

Howard ordered two other divisions under Major General Carl Schurz into the threatened sector. The Union soldiers ran into battle and set up to meet the rebel attack. Unfortunately, even with two divisions the Federal line was thin and there was a large gap in the lines between the XI Corps troops moving into place and the I Corps troops, still roughly where they had been during the fighting in the morning.

The rebels preparing to attack were from the division of Major General Robert Rodes, part of Dick Ewell's II Corps. That morning, Ewell had ordered Rodes' division and a division under Jubal Early to move directly to Gettysburg to support Heth. Lee sent a message to Early granting approval for Early's actions, but warned Early to not force a general battle until Confederate forces had been concentrated in the area.

Rodes had just arrived with his division of five brigades, marching around Gettysburg from the northeast to the northwest, and had immediately noticed the gap in the lines between Federal I Corps and XI Corps. He felt he could move on the I Corps line from the north in a flank attack and quickly roll up the I Corps. He had been warned that no major battle should begin until the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia was present, but he felt he had a chance he couldn't pass up.

Rodes ordered guns set up on Oak Hill to support the attack and organized his brigades for the assault. He did so hastily, without performing reconnaissance, and threw his men into the attack shortly after 02:00 PM, with the rebels advancing over the eastern slope of Oak Ridge. Despite Rodes' haste, the Federals had still had enough time to establish and extend their positions. The Confederate assault was a complete and suicidal botch. Lee's men had learned to be aggressive, and were accustomed to having it pay off; now they found that it could well be rash and fatal instead.

The attack was led by two brigades, one under Colonel Edward A. O'Neal and the other by Brigadier General Alfred Iverson JR -- though saying "led" is an exaggeration, since neither officer was at the head of their troops. O'Neal's Confederate brigade ran headlong into Baxter's Union infantry, who had set up a strong position behind a stone wall. Baxter's men hit O'Neal's advancing soldiers with a terrible hail of musket fire, taking down almost 700 of the brigade's roughly 1,700 men. Rodes later said: "The whole brigade was repulsed quickly and with loss."

O'Neal's brigade had been taken off the playing board. Baxter then decided to deal with Iverson's Confederate brigade, which was on the move to the south. Baxter ordered his men to double-time south and take up positions behind a stone wall, where they waited until the rebels were at close range. The Federals then stood up and hit the Confederates with a volley that laid out 500 rebels in a nice neat straight line; the Yankees then charged the Confederates and took 400 prisoners. Iverson's brigade had now also been removed from the board. Iverson, who was watching from the rear, became completely hysterical; one of his staff officers had to assume command and collect the shattered brigade.

As Iverson's men fell back off the battlefield, Rodes sent in two more brigades, one under Brigadier General Junius Daniel and the other under Brigadier General Stephen Dodson Ramseur. Daniel moved his men down MacPherson ridge, out of range of the Federals to the east, intending to get to the Chambersburg Pike and then hook up into the Union flank north of the road.

Daniel didn't know about the railroad cut north of the pike, which happened to be occupied by a Pennsylvania regiment that was using it as a convenient line of defense. The rebels ran into a heavy volley from the Pennsylvanians, who then charged the rebels. The Yankees were driven back by Confederate artillery and Daniel sent his men forward again, fueling a seesaw fight that chopped both the rebel and Yankee units to pieces. However, Daniel's men did not manage to break the Federal line in the railroad cut.

Ramseur, for his part, moved south towards the Union line, in fact roughly duplicating the path of Iverson's unlucky brigade and on a collision course with Union General Baxter's men. The rebels were warned off at the last moment by two of Iverson's officers who told them they were walking into a trap, and Ramseur adjusted his line of march in hopes of flanking the Federals from the north.

The Yankees had been bracing their line in anticipation of just such an attack. Baxter's brigade was part of a division under Brigadier General John C. Robinson, a tough old Regular officer noted for his remarkable beard, and Robinson had committed another one of his brigades, this one under Brigadier General Gabriel Rene Paul. Ramseur's Confederates ran into Paul's Yankees and the result was a grinding slugging match. Paul took a terrible head wound that tore his eyes out, and both his and Baxter's brigades were forced back slowly after they started running low on ammunition. The 16th Maine Volunteer Regiment acted as a rear guard and was almost completely destroyed. As they crumbled, the Maine men ripped up their regimental colors rather than see them taken.

BACK_TO_TOP* Robert E. Lee was watching this bloodbath from the top of Herr Ridge. Lee was trying to sort out the situation and when General Heth asked for permission to renew his attack, Lee replied: "No, I am not prepared to bring on a general engagement today. Longstreet is not up."

Lee could still see a fight going on to the northeast. He realized it was Jubal Early's division, which had just arrived on the battlefield and was advancing on the Union XI Corp's right flank. Lee felt forced to respond to events, and sent in Heth's division, along with a fresh division from A.P. Hill's III Corps under Major General William Dorsey Pender that had just recently arrived, to hammer the Federal lines to the south. Plans had been trailing events since the beginning of the battle, and even Lee wasn't able to reverse the trend.

Rodes had deployed his fifth brigade, under Brigadier General George Doles, to the east of Oak Hill in expectation of linking up with Jubal Early's division when it arrived. There was a small hill to the east, just short of the Harrisburg Road, that stood above otherwise open terrain, and Doles felt it would be a useful position to occupy in preparation for the arrival of Early's men.

However, the same insignificant hillock was spotted by Brigadier General Francis C. Barlow -- a division commander, leading one of the two divisions under Major General Schurz that had been sent northward to extend the Federal line. Barlow's men went forward and swept the rebels off the hill. Schurz ordered his other division, under Brigadier General Alexander Schimmelfennig, to move forward to ensure that Barlow's division wasn't flanked. This brought Schimmelfennig's men into contact with the rest of Doles' Confederates, and the fight went to a full roar.

It would not have been much of a contest, since Doles had a little over 1,300 men to face over 5,500 Federals, but Jubal Early arrived on schedule. Early's troops hit Barlow's men, who broke and fled back towards Gettysburg. These were the same divisions, mostly of German immigrants, that had done so poorly at Chancellorsville, and they were doing no better now. They did have good reason to run, since their line was tenuous and they were greatly outnumbered by Early's rebels -- but it still did nothing to improve the reputation of the "Dutchmen".

At the head of the Confederate counterblow was a brigade under the dashing Brigadier General John B. Gordon. Gordon was in pursuit of the fleeing Yankees on his great black stallion when he spotted a wounded Union officer lying on the ground. Gordon took pity on the man and dismounted, gave him water, and asked his name. "Francis C. Barlow," the man replied. Barlow had been seriously wounded in the chest by a bullet. Both men judged the wound mortal. Barlow asked to relay to his wife that his last thoughts had been of her. Gordon arranged for the message to be sent into Federal lines under a flag of truce, and had Barlow put in the shade of a tree before moving on with the fight.

Barlow was soon moved by rebel troops to a field hospital. Barlow actually survived his wound. He believed later that Gordon had been killed in action, but the two men met by chance in Washington after the war and became good friends. Gordon wrote: "Nothing short of resurrection from the dead could have amazed either of us more." The little hill over which the two men had fought later became known as Barlow's Knoll.

The entire Union XI Corps line was crumbling under Early's attack, with the routed Yankees flooding through the streets of Gettysburg and the rebels close behind. General Schimmelfennig was part of the flow until a rebel bullet hit his horse. He took refuge in a woodshed to escape the Confederates, staying there until the shooting was over. Early was triumphant at the success of his troops, saying later: "It looked indeed as if the end of the war had come."

* The Confederates had been making gains against I Corps as well. Heth had gone forward with his men, though he didn't stay there for long. He was wearing a civilian hat that was too big for his head, and his clerk had padded the sweatband with rolled-up sheets of paper to make it fit. A bullet struck Heth along the sweatband, with the rolled-up paper absorbing much of the blow; the slug still cracked his skull and knocked him unconscious. Brigadier General James Pettigrew assumed command.

The men of Union I Corps, as they had already proved earlier in the day, were not easily intimidated. One Confederate officer put it simply: "The fighting was terrible." Confederate color-bearers dropped in succession. The Iron Brigade fought back tenaciously, but the pressure was more than they could bear and they cracked. In fact, in that day's fighting the Iron Brigade was all but destroyed, losing over 1,150 of the 1,800 men in its ranks. Private Maloney, who had captured General Archer, was among the dead. The Iron Brigade would never be the same again. A rebel officer riding into the woods through the wreckage of the Federal position heard the "dreadful -- not moans but howls -- of the wounded. I approached several with the purpose of calming them if possible. I found them foaming at the mouth as if mad."

The Federal defense had been broken, but the Yankees had not been routed. I Corps troops fell back to Seminary Ridge and reformed into a defensive line. They had little time to prepare before the rebels, in the form of General Pender's division, hit them again. A battery of Union artillery under Lieutenant James Stewart managed to stall the Confederates by throwing double-shotted canister into their ranks as fast as possible. One of the Federal gunners wrote later:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

Up and down the line, men reeling and falling; splinters flying from wheels and axles where bullets hit; in rear, horses tearing and plunging, mad with wounds or terror; drivers yelling, shells bursting, shot shrieking overhead, howling about our ears or throwing up great clouds of dust where they struck; the musketry crashing on three sides of us; bullets hissing, humming and whistling everywhere. Smoke, dust, splinters, blood, wreck and carnage indescribable.

END_QUOTE

The Federal defense crumbled and broke again, with some I Corps troops falling back into Gettysburg to run into the tangle of XI Corps men there, and others falling back into the relative safety of the Union defense Howard had earlier ordered set up on Cemetery Hill to the south.

* Major General Winfield Scott Hancock rode into town with a group of aides at about 04:30 PM. Meade, on hearing of the death of Reynolds, had told Hancock to turn command of his II Corps over to John Gibbon and ride to Gettysburg to take charge.

Hancock arrived to see the fight going badly for the Federals. One of his group commented: "Wreck, disaster, disorder, almost the panic that precedes disorganization, defeat, and retreat were everywhere." Fortunately, everybody respected the professional, courageous, and striking Hancock, and the news that he had arrived in itself helped restore calm.

Hancock found Howard near Cemetery Hill and told him that Meade had placed him, Hancock, in charge. Howard didn't accept it: "I am in command and rank you." Howard's corps had crumbled under similar circumstances at Chancellorsville under Stonewall Jackson's flank attack, and Howard's pride didn't allow him to give up control when faced with a second such disastrous humiliation. Hancock did not argue the matter with Howard. Hancock assessed the battlefield situation and looked over the terrain. The rebels now held Gettysburg itself, but that was of no great importance. What was more interesting was the complex of hills and ridges to the south of the town:

Hancock liked what he saw and told Howard: "I think this is the strongest position by nature on which to fight a battle that I ever saw, and if it meets with your approbation, I will select this as the battlefield." If Howard insisted on being in charge, Hancock would at least pretend to go along. Howard agreed, and from that moment on, Culp's Hill, the Round Tops, Cemetery Ridge, and other features in that area ceased to be local names and became part of history.

Although the position was strong, it was very extended and the survivors of XI Corps and I Corps could not hold it by themselves for long. Hopefully they wouldn't have to, since Major General Daniel E. Sickles was on the way with III Corps and Major General Henry W. Slocum was moving up with XII Corps. They weren't there yet; nobody was sure when they would arrive; and the battered soldiers on the spot had to hold out for as long as they could.

Hancock braced up the defenses on Cemetery Hill as best he could, then he ordered Abner Doubleday to send I Corps men over to occupy Culp's Hill. Doubleday was frazzled and protested that his men were badly used up. This was undeniably true, but irrelevant under the circumstances. Some sources say Hancock roared at Doubleday and ordered him to send in every man he had, but that seems a bit out of character. Hancock was capable of blistering abuse when necessary, but he was cool under pressure; Doubleday's men had clearly been severely mauled, and there was no intelligent reason to browbeat Doubleday under such conditions if a sensible reply could do the job. Other sources say that Hancock replied, calmly: "I know that, sir. But this is a great emergency, and everyone must do all they can."

In any case, ragged survivors of Wadsworth's division were ordered into position on Culp's Hill. There was no more than a brigade's worth of effectives left, but Culp's Hill was forested and covered with great boulders, making it a natural fortress, and the troops were soon joined by the lead division of Slocum's XII Corps. The second division of XII Corps followed. Slocum was not with his troops; he had judged the battle for Gettysburg likely to be another defeat, and so wanted to distance himself from the failure. Slocum's absence suited Hancock fine, since he could now give XII Corps orders. He sent the second division south to occupy the Little Round Top.

The Federals took up their positions with little interference, though Hancock had been expecting to be confronted with waves of howling rebels at any moment. As the Union men took up positions on the hills, their confidence increased. Hancock himself inspired courage, and experienced soldiers saw, just as Hancock had, that the Federal position was a strong one. Some even saw in it the possibility of revenge for the slaughter inflicted by the Confederates on Yankee troops at Fredericksburg.

As the Federals moved into their positions, Hancock sent a message to Meade indicating that the situation had stabilized. In fact, things seemed very promising. Slocum finally decided that he needed to be at the head of his corps, arriving on the battlefield at about 07:00 PM. Hancock turned over command to Slocum and rode off to report back to Meade at his field headquarters in Taneytown, Maryland, about 12 miles (19 kilometers) away.

BACK_TO_TOP* Lee was on Seminary Hill, inspecting the Federal positions on Cemetery Hill. Of course Lee recognized the military usefulness of the terrain as quickly as Hancock did, and so Lee ordered A.P. Hill to take Cemetery Hill. Hill had to refuse the order: his men were badly beaten up themselves, and they were almost out of ammunition. Hill never turned down a fight if he had the least hope of winning it, and so Lee did not press him further.

Lee sent a courier off to tell Dick Ewell, north of Gettysburg, to take up the attack. Lee didn't have time to write up the orders, simply saying that Ewell should "press those people in order to secure possession of the heights." He was to do so "if practicable", but to "avoid a general engagement" until reinforcements arrived.

While Lee was waiting for Ewell to begin his attack, Longstreet arrived in advance of his troops. Longstreet saw an opportunity at Gettysburg, but it was not the same one that Lee saw. Longstreet felt that the Army of Northern Virginia should swing around to the southeast of the Army of the Potomac and take up a strong defensive position. The Federals were notoriously touchy about any threat to Washington, and would feel compelled to attack.

Longstreet was inclined to defend and then counterpunch; Lee was inclined to the bold offensive. Lee saw an opportunity in the present to get the upper hand and keep it, allowing the Army of Northern Virginia to destroy the Army of the Potomac as Meade tried to feed his forces into the battle incrementally. Lee replied: "No, the enemy is there, and I am going to attack him there." Longstreet understood the strength of the terrain that the Federals were occupying. He argued with Lee: "If he is there, it is because he is anxious that we should attack him -- a good reason, in my judgement, for not doing so."

Lee brushed him off: "I am going to whip them or they are going to whip me." Lee's blood was running hot, and Longstreet knew there was no arguing with him for the moment. Longstreet didn't forget the matter, though, and for the rest of the battle Lee and his best surviving lieutenant were to be at odds, spoken or not, on the way things should be done.

* Lee waited for Ewell to begin his attack; and waited; and waited. Nothing happened. Longstreet wasn't happy about the idea of taking the offensive on the Federals, but as he watched Union reinforcements arrive and Yankee soldiers digging in, he suggested to Lee that if he wanted to attack, he needed to do it quickly.

Lee received a distraction in his wait in the form of a visit from two of Stuart's cavalry troopers, who relayed to Lee the various misadventures Stuart's command had endured since setting out north. Lee was very unhappy with Stuart's absence, but it was at least a relief to know that Stuart and his men hadn't been bagged by the Yankees, and would rejoin the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia soon.

Finally, the sun was starting to drop low in the sky, and at about 07:00 PM Lee rode off to Ewell's headquarters to find out what the hangup was. Ewell, normally an aggressive and astute commander, was apparently hot and tired that day, since his behavior was uncharacteristically listless. Even after his troops cracked Union XI's Corps lines, he did not press forward in pursuit. He did personally ride into Gettysburg to investigate the situation, in the company of John Gordon. To his shock, Gordon saw Ewell struck by a bullet. Gordon cried out: "Are you hurt, sir?!" Ewell, who had lost a leg earlier in the war, saw a bit of humor in the question, and replied: "No, no, it don't hurt a bit to be shot in a wooden leg."

When the courier arrived with orders from Lee to attack, Ewell remained in his daze and did not organize an assault. Part of the reason appears to be that Ewell had never taken orders directly from Lee before, and Lee tended to phrase orders in forms that resembled requests, in this case telling Ewell to advance "if practicable". Most of his senior officers were very aggressive and a request was all that was required, but Ewell's previous boss had been the late Stonewall Jackson, who told Ewell exactly what to do, and expected it done to the letter even if it killed Ewell and every man in his command. Lee's orders in contrast seemed casual and carried no sense of urgency, and Lee's instructions to "avoid bringing on a general engagement" no doubt aggravated Ewell's passivity.

When Lee arrived to find out why Ewell failed to attack, an odd scene followed in which Lee tried to press for an attack; Jubal Early argued that the Federal position was too strong; and Ewell said almost nothing. However, by that time, an attack was no longer "practicable". The Union III Corps and XII Corps were arriving on the field. The Federals were now strong enough to give Ewell a severe bloodying if he attacked, and there was no more serious fighting that evening.

Recognizing the impracticality of an attack on the north, Lee suggested shifting Ewell's forces for an assault on the Union line at its southern end. Early protested again, arguing that such a shift would be time-consuming, and that the presence of Confederate forces to the north would be necessary to prevent the Federals from shifting their own troops to meet an attack elsewhere. This scenario meant that Longstreet's force would bear the burden of an assault, and Longstreet was at heart a defensive fighter. Lee left the meeting and rode back to his headquarters camp on Seminary Ridge, near the Chambersburg Pike, and thought over the situation.

Had Ewell gone forward that evening when Lee had wanted him to, the Confederates might well had cracked the Union line. However, given the spontaneous way the battle had grown from beginnings that were largely accidental, the idea that either side could have fought like a precision machine that day is not credible. The result was that the two sides had bloodied each other, with both sides taking thousands of casualties, but neither side had obtained a clear advantage in the fighting. They ended the day in roughly the same ratio of strength they had possessed before the shooting began.

By the time Lee arrived back at his headquarters he had rejected Early's arguments, and sent orders to Ewell to shift his forces south for an attack. On receiving these orders, Ewell hurriedly rode to Lee's headquarters to tell Lee that one of his officers had scouted out the Federal positions on Culp's Hill and judged that it could be taken by assault.

Lee was encouraged by this news. If Ewell managed to take Culp's Hill, the whole Federal position would come unhinged. Lee canceled his orders and instructed Ewell to prepare for the assault. After Ewell left, Lee, having given the matter more thought, decided that he would initiate the fight with Longstreet to the south, and sent a courier to Ewell to instruct him to wait for the sounds of Longstreet's attack before moving on Culp's Hill. By that time, it was about midnight, and Lee finally decided to get a few hours of sleep.

* Hancock arrived in Taneytown at about 09:00 PM. Meade had not been enthusiastic about fighting at Gettysburg at first, and much of the news he had received, particularly concerning the death of John Reynolds, had not made him more optimistic. However, the message that Hancock had sent Meade earlier and Hancock's personal testimony was persuasive. Meade broke camp and headed north at about 10:00 PM, arriving at Gettysburg in the dark hours of the morning.

Further Union reinforcements had arrived in the meantime. Sickles' III Corps was assigned to take up positions on Cemetery Ridge, and was braced by Hancock's own II Corps, led to the battlefield by John Gibbon. George Sykes' V Corps arrived in the early hours of the morning. The only major element of the Army of the Potomac still missing was John Sedgwick's VI Corps, which was moving by forced march and would hopefully show up the next morning.

Meade held a council of war at the gatekeeper's quarters at the graveyard on Cemetery Hill, asking General Howard: "Well, Howard, what do you think? Is this the place to fight a battle?" Howard answered: "I am confident we can hold this position." -- and the other officers agreed. Meade replied: "I am glad to hear you say so, gentlemen. I have already ordered the other corps to concentrate here, and it is too late to change."

BACK_TO_TOP