* The morning after the Battle of Chancellorsville, Joe Hooker had an opportunity to renew the fight on good terms against the Confederates. He didn't have the nerve, instead withdrawing his force. Robert E. Lee saw the defeat of the Army of the Potomac as an opportunity to take the war to the North, and led his Army of Northern Virginia across the Potomac. Hooker followed the Confederates, but there was no more confidence in his leadership; he resigned under pressure, to be replaced by George Meade.

* Despite the confusion, the Federals managed to organize a defense. By the next morning, Sunday, 3 May, elements of Couch's II Corps and Slocum's XII Corps facing Stuart had cleared fields of fire and built breastworks and abatis -- which were trees trimmed down and their branches cut to points to impede an attack. North of this line, Meade's V Corps and Reynolds' I Corps, which had forded the Rappahannock during the night, protected Federal lines of retreat back to the river.

Sickles' III Corps held the southern end of the Federal position, forming a salient centered on Hazel Grove, about a mile south of Chancellorsville. They had pulled back from their forward thrust at Catherine Furnace after dark, enduring a hideous gauntlet of fire from both Confederates and confused Union troops. What remained organized of Howard's routed XI Corps protected the Army of the Potomac from an attack from the east. Howard's men had taken a severe beating, but there was no immediate danger from that direction in any case.

There was something unreal about the situation that morning. With the arrival of Reynolds and his men, Hooker had 76,000 effectives in a reasonable defensive position, threatened by 43,000 rebels who were split in half. The Federals had been badly shaken by Jackson's flank attack but not seriously damaged in terms of numbers, equipment, or (at least as far as the troops in the line were concerned) morale. They should have at least been an intimidating prospect for an attack -- and if they took the offensive, they would be able to destroy the separated Army of Northern Virginia one part at a time.

Unfortunately, Couch's assessment of Hooker was correct: he was a beaten man. He refused to attack, simply sending orders back to Sedgwick at Fredericksburg for him to come to his relief -- and then Hooker destroyed his chances of even being able to conduct an effective defense. He had been worried by the vulnerability of the salient occupied by Sickle's III Corps. The night before, a rebel probe had in fact cut off Sickles, and Couch later wrote that it caused Hooker "great alarm, and preparations were at once made to withdraw the whole front, leaving General Sickles to his fate; but that officer showed himself able to take care of his rear, and communication was restored at the point of the bayonet."

During the night, Sickles requested reinforcements but nobody would wake Hooker. When Hooker did wake up that morning, he refused the request and ordered Sickles to fall back towards Chancellorsville. Sickles was entirely reluctant to give up the high ground around Hazel Grove, but orders were orders, and so at about 6:00 AM he fell back.

Then Jeb Stuart launched his attack. Advance units occupied Hazel Grove without effective opposition, capturing 100 Yankees and three guns of Sickles' rearguard. The Confederates had moved up 30 guns near that place during the night and immediately set them up on the high ground. From there, they could take the entire Union position under effective fire, and did so without delay.

A.P. Hill's division, now under Brigadier General Henry Heth, took the lead in the drive on the Federal position across the Plank Road. With help from the artillery firing from Hazel Grove, they pushed the Federals back, but the rebel advance quickly fell into confusion in the rough terrain. The battle disintegrated into a terrible brawl with Confederate and Union regiments attacking and counterattacking, trees smashed apart by shot and shell to crush soldiers with falling limbs, fires spreading through the underbrush to burn the wounded alive while their cartridge boxes cooked off and tortured them further.

Among the dead was Hooker's friend Hiram Berry, killed by a rebel sharpshooter. Berry's corpse was carried off the field. When Hooker saw the group of officers bearing the body, he called out: "Who have you got there, gentlemen?" On finding it was Berry, Hooker jumped off his horse and said: "My God, Berry! Why was this to happen? Why was the man on whom I relied so much to be taken in this manner?"

As the fighting raged, some Federals drifted to the rear, others stood their ground and fought back stubbornly. Heth's rebels took an ugly beating, and many Confederate regiments became dispirited with fear. Fellow regiments coming up to bolster the attack became confused in some cases, firing into their comrades in the front line. Others advanced past regiments who hugged the ground, too frightened to move, and were badly torn up in turn.

Even Jackson's legendary Stonewall Brigade, bled to exhaustion in a charge, had to be rallied to charge again by Stuart, who rode among them, mocking the Yankees and encouraging the soldiers to get up and fight once more. They advanced to a hundred yards of the main Federal artillery battery on top of high ground named Fairview Heights, behind the center of the Union line, and were then torn to pieces by massed canister fire.

Although the Confederates were taking a beating, they were dishing one out as well, and the Union men were being slowly worn down. Fire from the Confederate battery at Hazel Grove was proving particularly troublesome. Under pressure, at about 9:00 AM troops from Major General William French's division began to fall back from their positions astride the Plank Road, and the gunners on Fairview Heights had to pull back as well. The Union soldiers fell back in reasonably good order and set up a new line, closer to Chancellorsville.

The fighting revealed an unlikely hero in the front lines, a pretty young lady named Annie Ethridge who wore sergeant's stripes on a black riding habit. Annie had been a laundress with the 3rd Michigan when that regiment went to war. The other laundresses had left when the regiment marched off from Washington to fight, but Annie had stayed, to become a cook in the officer's mess. She was described as a quiet, modest young woman who was adored by the entire 3rd Michigan. Any man who said anything unkind of her faced the wrath of the entire regiment. That morning she rode into the thick of the fighting on her horse, carrying canteens of coffee and a sack of hardtack. The men tried to make her go back, but she insisted they have something to eat and drink and betrayed not the slightest fear. She then went to encourage a Union battery that had been badly cut up by the Confederate barrage, and talked them into holding their ground.

A short time later, Hooker was standing on the porch at Chancellor House when a Confederate shell from the batteries at Hazel Grove hit one of the pillars on the front porch and split it. Part of the pillar hit Hooker in the head, and he fell down unconscious. Some of his officers thought he had been killed, but they managed to get him up again. Hooker was partially paralyzed and in pain. Darius Couch of II Corps came to Hooker for instructions, but Hooker neither gave him instructions nor suggested that Couch, the next in the chain of command, take over.

Couch did what he could to stabilize the line. A critical portion of his defense was held by Colonel Nelson Miles and his men. Miles was still recuperating from a wound he had taken at Fredericksburg, but he managed to hold off several Confederate drives. He was then wounded by a sharpshooter and carried off the field. The bullet had gone into his stomach, fractured his pelvis, and stopped in his thigh; everyone thought he would die, but he would survive the wound and return to duty.

The shrinking Federal position was under increasing stress as the rebels focused artillery fire into the Yankee defense. Couch believed he could save the day with a determined counterattack, but when he was summoned by Hooker at 9:30, he was simply ordered to lead the army northward and off the field of battle. Using Winfield Scott Hancock's division as a rearguard, the bitterly disappointed Couch pulled the Army of the Potomac back to a line north of Chancellorsville. The withdrawal was completed at noon. The rebels tried to press an attack on the new Yankee lines, but the defenses were solid: the attack was broken up by Federal artillery, directed by Brigadier General Charles Griffin.

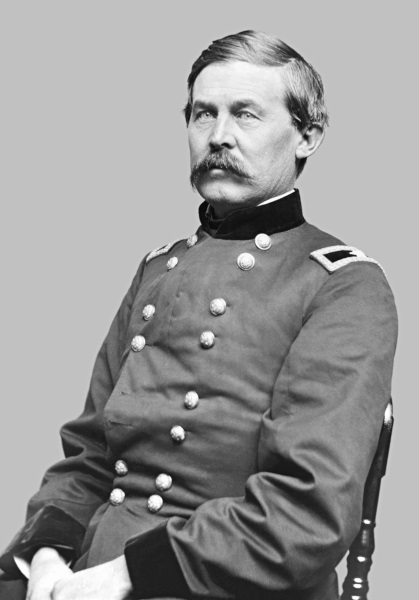

Griffin was a lean, tough regular with a walrus mustache who was very popular with his men. He had specifically asked Meade to use artillery instead of infantry to check the attack. Meade gave him the go-ahead as long as Griffin thought the guns could do the job. He replied: "I'll make them think Hell isn't half a mile off!" He lined up a dozen guns and hit the rebels with double charges of canister at short range. The Confederates, badly torn up, decided they'd done enough for one day.

In any case, Lee and Stuart's forces had finally linked up. Lee himself rode up towards Chancellor House, which was burning furiously, and was greeted by the cheers of his men. Lee was about to press the attack once more against the Federals, when a messenger brought him news: General Sedgwick was attacking the Confederate forces at Fredericksburg.

* Sedgwick had received orders late the night before to cross the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg and come to the aid of the rest of the army at Chancellorsville by sunrise. In fact, when Sedgwick got the message, he was already across the river with most of his command, just south of Fredericksburg. However, he still had to penetrate the defenses that had frustrated the Army of the Potomac in December, and the Confederates had improved them since then. The trenches were manned by 9,000 rebels under Jubal Early, and presented a deadly obstacle.

Sedgwick ordered Brigadier General John Gibbon, still back at Falmouth with his division, to lay a pontoon bridge across the Rappahannock and join the attack. Gibbon responded quickly, but found that in the moonlight the rebels were easily picking off his engineers. He decided to wait for dawn.

Sedgwick moved upstream during the night. Once he and his men arrived at Fredericksburg at dawn, Gibbon and his men were able to move across the river largely unmolested. Goaded by messages from Hooker and his chief of staff, Dan Butterfield, Sedgwick immediately sent his divisions forward to attack the Confederates on Marye's Heights above the town. The rebels were set up behind a wall, establishing a very strong position; Burnside's assaults on the heights in December had proven disastrous. Sedgwick's first attack foundered in blood, as had happened under Burnside. Sedgwick, watching the fiasco, said: "By Heaven, sir, this must not delay us."

A second attack was organized. Some of the commanders, remembering the futile charges of the December battle, formed their men into columns instead of lines, then ordered them to charge at a double-quick with unloaded rifles and overwhelm the enemy with the bayonet. The Federals pressed their assault but were thrown back. However, men of the 7th Massachusetts, hiding behind a fence, noticed one section of the rebel line that seemed lightly held. A party of stretcher-bearers set out under truce confirmed that was the case, and the Massachusetts men rushed the weak point.

On their left, Colonel Thomas Allen of the 5th Wisconsin sent his men with fixed bayonets, ordering them: "When the signal FORWARD is given, you will start at double-quick, you will not fire a gun, and you will not stop until you get the order to halt. You will never get that order." They went forward in a rush and the Union men poured over the wall, grappling with the rebels in savage hand-to-hand fighting. Other Federal units joined in, and Early's men crumbled. The rebels managed to collect their equipment and flee south. It was about 11:00 AM.

Sedgwick had done the seemingly impossible, and it was essential that he follow it up quickly. He did not. He was a common-sensible, plain, methodical man who was generally not inclined to hurry, and didn't manage to get his men on the move up the Turnpike towards Chancellorsville for several hours. By that time, Lee had sent Lafayette McLaws' division to block the Turnpike. The two forces made contact at about 3:30 PM. Sedgwick's men charged the Confederates and broke their lines, only to be thrown back and almost crushed when the rebels threw in reserves.

Sedgwick had 19,000 men to McLaws' 10,000; however, Sedgwick had been only able to commit a single advance division of 4,000 men to the attack. His other divisions arrived a short time later, but it was too late in the day to organize another attack on McLaws.

After the sun went down, Lee ordered Richard Anderson to take his division and reinforce McLaws. That left a mere 25,000 men to keep an eye on Hooker, but Lee had correctly decided Hooker had no fight in him. An opportunity was available to destroy Sedgwick's force, and Lee wanted to take advantage of it. Lee sent orders to Early for him to return to Fredericksburg and threaten Sedgwick from the rear.

BACK_TO_TOP* When the sun came up on Monday, 4 May, Hooker was actually in the strong position he had thought he had been in three days earlier. His men, having long ago learned the survival value of digging in, had fortified their contracted lines with great skill. Had Lee decided to attack then, he would have been bloodily driven back.

Lee was busy elsewhere for the moment, focused on wiping out Sedgwick's corps, and didn't have the resources present in front of Hooker's lines to make such an attack. In fact, the rebel forces there were in grave danger from a counterstroke, and many of the Union men knew it. If Joe Hooker knew it, he didn't seem concerned, and his men spent the day in relative quiet.

While Hooker sat, Sedgwick was concentrating on the business of survival. Early's forces had chased Sedgwick's pickets out of Fredericksburg, and as the day wore on, Sedgwick found him and his 19,000 men confronted with a rebel force of 21,000 that was trying to encircle him. Sedgwick moved his corps northward toward the river and set his men up in a defensive horseshoe, while engineers laid down two pontoon bridges over the Rappahannock at a place called Scott's Mill Ford. Lee planned to destroy the bridges with artillery, and then attack Sedgwick's position from south and west.

Lee didn't get his forces organized until late in the afternoon. It wasn't until 5:30 PM that the attack jumped off; after a short and nasty fight, the assault became confused in the rough terrain. Despite the efforts of Confederate artillery, the two pontoon bridges were still intact by the time nightfall put a stop to the attacks. Sedgwick was still worried and at midnight sent a message to Hooker, pointedly requesting permission to withdraw.

Hooker had called a meeting of his corps commanders to debate the question of withdrawal. Meade, Howard, Reynolds, Couch, and Sickles arrived and were asked to vote on the matter. Meade, Howard, and Reynolds voted to stay, while Sickles and Couch voted to withdraw. Couch actually wanted to fight, but had no confidence in Hooker's leadership. The vote was in favor of fighting -- but Hooker ignored it, and ordered the army to retreat anyway. Reynolds loudly complained, apparently within hearing of Hooker: "What was the use of calling us together at this time of night when he intended to retreat anyhow?!"

Sedgwick had all his men back across the river and had dismantled his pontoon bridges by sunrise on Tuesday, 5 May. Evacuating the bulk of the Army of the Potomac from its position north of Chancellorsville was more complicated. Matters were made worse by the fact that the dispirited Hooker was one of the first to return across the river, leaving the organization of the retreat to his corps commanders, and by torrential rains that bogged down the soldiers and kept the engineers busy extending the pontoons. By the morning of Wednesday, 6 May, the evacuation was complete. The battle of Chancellorsville was over.

* The news of the defeat made its way back to the White House through a telegram from Dan Butterfield. President Lincoln cried out: "My God! My God! What will the country say?!"

Hooker's soldiers straggled back to Falmouth, to be joined a bit later by Stoneman's cavalry troopers. The Union cavalry had accomplished little on their raid, having struck at a large number of insignificant targets without seriously inconveniencing the Confederates. Hooker was furious; Stoneman's days were numbered. In fact, Hooker was busily blaming the defeat on everyone but himself, while his generals loudly bickered with him and among themselves. Nobody was much fooled by Hooker's bluster. Darius Couch asked to be transferred; he refused to take orders from Hooker any more.

Critics said that Hooker must have been drunk to have behaved as he had. Couch disagreed, saying that a few drinks would have likely done Hooker a lot of good. Some time later, Hooker admitted: "I was not hurt by a shell, and I was not drunk. For once I lost confidence in Joe Hooker, and that is all there is to it."

Darius Couch went back to Pennsylvania and out of the action for the rest of the war, It is one of the interesting might-have-beens of the war to consider what would have happened had Hooker been disabled by that cannonball at Chancellor House, and the cool and aggressive Couch had risen to the command of the Army of the Potomac. Couch was replaced in command of II Corps by Winfield Scott Hancock.

There was still a silver lining to the disaster at Chancellorsville if anyone were sharp-eyed enough to see it. There was grumbling and complaint after the battle among the public and in the ranks, but it didn't amount to very much. Neither the country nor the Army of the Potomac seemed very much deterred by the defeat.

For the Confederacy, Chancellorsville was a brilliant victory. Robert E. Lee had taken on a force almost twice the size of his own and sent it back to where it had come from, inflicting greater casualties than he had taken.

It was, however, only a tactical victory. Lee's silver cloud had a very black lining. The Union Army of the Potomac had been hurt but not disabled. The Federals had taken 17,000 casualties, the Confederates 13,000, but relative to the size of forces the Confederates had taken a more painful loss they were less able to make good. The arrangement of the pieces on the chessboard remained unchanged.

One of the Confederate casualties was of enormous significance. Stonewall Jackson seemed to be quickly recovering from the loss of his arm, but on 7 May he was diagnosed with pneumonia. Hopes that he might survive the illness were lost when the doctors told Jackson's wife they did not think he would live through the day. Jackson rambled, obtaining momentary clarity in the midafternoon to say: "Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees." He then faded, rambled more, and died. He was 39 years old.

Jackson's body lay in state in the Confederate Capitol in Richmond, and was observed by crowds. The body was then taken to Lexington, Virginia, where Jackson had taught at the Virginia Military Institute, and put to rest. The battle had cost Robert E. Lee the services of one of his best subordinates, as well as dozens of other senior officers. While the South celebrated, Lee worried about the future.

* Nonetheless, Robert E. Lee knew that if he did not inflict a decisive defeat on the Union, there would be nothing to prevent the more powerful North from eventually overwhelming the Confederacy. Remaining on the defensive would be deferred suicide. That meant Lee had no choice but to move north again, as he had the previous year, in hopes of putting Northern cities, particularly Washington, at risk. His own army was also desperately in need of food and other supplies. Such materials were abundant above the Potomac, and taking the war out of northern Virginia would give its citizens a breathing spell from the wastage that accompanied the presence of large armies.

On 14 May 1863, Lee went to Richmond to discuss his plan with Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his cabinet. They were all uneasy with the idea of another invasion of the North. Vicksburg, Mississippi, was then under siege by Union forces; if it fell, the Yankees would have effective control of the Mississippi River, and the Confederacy would be cut in half. Sending the Army of Northern Virginia to relieve the besieged city seemed the more prudent plan. Lee argued his case for three days, and in the end the cold logic of the situation and the force of his personality won out. Another invasion of the North was a desperate and risky measure, but the alternatives were worse.

Before beginning on the campaign, Lee reorganized his forces. Previously, the Army of Northern Virginia had been organized into two corps of about 30,000 men each, one under Lieutenant General James Longstreet and one under Stonewall Jackson. Jackson was now dead and buried, leaving a major hole in the army's command structure.

Lee took the occasion to divide the army into three smaller corps that he judged more manageable, announcing the names of the corps commanders on 30 May. I Corps command went to Longstreet. II Corps commander was Lieutenant General Dick Ewell. III Corps command went to A.P. Hill. That was something of a gamble on Lee's part: Hill was a great fighter, but his aggressiveness made him impatient, and on occasion he had proven inclined to attack without waiting for orders.

Lee also chose to bolster Jeb Stuart's cavalry command by assigning him four additional cavalry brigades that had previously been independent. One of the brigades was under the command of Brigadier General William E. Jones, a tough disciplinarian so cantankerous that he was known as "Grumble" by his men. Jones was sour and wore plain, even raggedy, clothes; Stuart was genial and flashy, a show-off who wore a plumed hat and red-lined cape. The two men couldn't stand each other.

On 3 June 1863, elements of the Army of Northern Virginia began to shift their positions in preparation for the offensive into the North.

BACK_TO_TOP* Joe Hooker was quickly aware that the Confederates were on the move. He had been provided intelligence on 27 May indicating that the Army of Northern Virginia had received marching orders, and on 4 June got word from balloon observers that the rebels were moving out of the Fredericksburg area.

Hooker had regained some of his old bluster, and suggested to Washington that the Army of the Potomac move across the Rappahannock, then "pitch into" the Confederates in the area. President Lincoln immediately rejected the idea that Hooker's army should try to cross a major river when the whereabouts of Lee's army were completely unknown. Lincoln believed the army could become "entangled on the river, like an ox jumped half over a fence and liable to be torn by dogs front and rear, without a fair chance to kick one way or gore another."

Hooker collected more intelligence and soon learned that Confederate cavalry were assembling near Culpeper, Virginia, at a whistle-stop town on the Rappahannock named Brandy Station. Hooker sent out his cavalry corps under Brigadier General Alfred Pleasonton to confront Stuart's troopers. Pleasonton divided his forces into two parts. Three brigades of cavalry and one of infantry under Brigadier General John Buford were sent a few miles upstream of Brandy Station to attack the rebels from the front. A larger force of two divisions, one under Brigadier General David McMurtie Gregg and another under French-born Colonel Alfred Duffie, were sent a few miles downstream to circle around and strike the rebels from the rear.

The Union troops moved into place in the dark morning hours of 8 June. Unfortunately, Duffie's division got lost and Gregg's division was forced to wait, throwing the downstream movement off schedule. Upstream, Buford's lead brigade moved across the river at daybreak, led by Colonel Grimes Davis.

Davis's men roared down the road towards Brandy Station, first encountering a unit of about 100 rebels who had been rudely awakened by the attack. The Confederates were forced to withdraw, but a rebel lieutenant who had been left behind managed to ride up on Davis and put a pistol ball into his head, killing him. Davis, a Mississippian who had stayed with the Union, was a notably energetic and bold officer, and his death robbed the Union cavalry of a potentially significant leader.

By that time, Jeb Stuart was aware of the trouble. He ordered the wagon train he had assembled to support his movement north to the rear, and sent reinforcements to deal with Buford's men. The Union troopers finally ran up against stiff Confederate resistance, and their charge faltered. They fell back, dismounted, and formed up a line along with infantry that had moved forward in support.

In the meantime, the Federal force under Gregg and Duffie had sorted itself out and was moving to attack Stuart's force from the rear. Grumble Jones reported the movement to Stuart, who dismissed it, saying: "Tell General Jones to attend to the Yankees in his front, and I'll watch the flanks." When given this response, Jones commented: "So he thinks they ain't coming, does he? Well, let him alone, he'll damned soon see for himself."

Gregg's column advanced on Brandy Station while Duffie led his men further around the Confederate rear. As Gregg's men moved up the road to Fleetwood Hill, which commanded the approach to Brandy Station, they were spotted by Major Henry McClellan, Stuart's adjutant. Stuart had run off to fight Buford's men with three brigades, leaving McClellan with only a handful of troopers -- but McClellan was a fighter and wasn't going to be run off. He found a light howitzer with a small supply of ammunition, and ordered his men to fire on the Union column.

The Federals at the head of the column, a brigade under Colonel Percy Wyndham -- a fiery British adventurer in Union blue -- paused in response to the fire. The Yankees were uncertain of rebel strength and decided to wait for the main body to come up the road. In the meantime, the boom of the howitzer finally alerted Stuart to the fact that there was something wrong in his rear.

Stuart sent four more guns and two regiments of Grumble Jones' troopers back to stop Gregg's division. They arrived at Fleetwood Hill just as the little howitzer ran out of ammunition. Wyndham's cavalry was in a full charge up the hill and ran straight into Jones' troopers. The result was a violent collision, with the Union cavalry smashing through and riding over the rebel horsemen. Gregg's men rode up the hill, to encountered more Confederate soldiers coming up as reinforcements. They put a stop to the Union charge, with the Union troops falling back, pressed by the rebels. Gregg sent a messenger to Duffie to ask him to assist -- but by the time Duffie arrived, the Confederates had stabilized their defense, and were not inclined to be pushed out.

In the meantime, to the northeast, Buford had made another drive against the Confederates, but despite fierce fighting the Federals were unable to break through. By that time, it was late afternoon and Pleasonton realized there was nothing more he could do. At 4:30 PM, he ordered his forces to withdraw, and they did so in good order.

The battle of Brandy Station was in almost any terms a Confederate victory. There were 866 Union losses to only 523 Confederate casualties. Among the rebel casualties was Brigadier General W.H.F. "Rooney" Lee, Robert E. Lee's 26-year-old son, who was wounded in the thigh while leading a cavalry charge. The Federal attempt to smash Jeb Stuart's cavalry had failed, and Stuart was pleased with the results.

However, there was a dark side to the victory. Stuart's cavalrymen were accustomed to riding rings around the Yankees. While they did beat the Federals at Brandy Station, they were hard-pressed for a time to do it. The Union cavalry was clearly not the gang of clumsy plowboys they had once been. Pleasonton's men were proud of their performance, and the days when Confederate cavalry could do what it pleased were fading. Even Henry McClellan would write that the battle of Brandy Station "made the Federal Cavalry."

* Stuart was forced to spend a week reorganizing his force. The Confederate offensive was on a timetable and did not wait for him.

On 10 June, Ewell put his II Corps on the road. He accompanied the march in a buggy. They crossed into the Shenandoah Valley through Chester Gap, and by 13 June were converging on the town of Winchester, in the northern part of the valley.

There was a force of 5,100 Union soldiers in Winchester under the command of Major General Robert H. Milroy. The War Department had been wiring Milroy for a week, pleading with him to withdraw to Harper's Ferry, 30 miles (48 kilometers) to the north, but Milroy felt his defenses were strong enough to hold. The Confederates made contact with Milroy's men, and in response Milroy ordered them to fall back to three forts north and west of Winchester. President Lincoln did not share Milroy's confidence, and the next day wired the general's commander:

GET MILROY FROM WINCHESTER TO HARPER'S FERRY IF POSSIBLE. IF HE REMAINS HE WILL GET GOBBLED UP, IF HE IS NOT ALREADY PAST SALVATION.

By this time, Dick Ewell's troops were moving into position to attack the critical West Fort. Their movements went unnoticed, even though Milroy had himself hoisted to the top of a flagpole in the West Fort in a basket to survey the countryside with a spyglass.

At about 5:00 PM on 14 June, the rebels went forward under the support of 20 guns in an enthusiastic charge, and brisk fighting followed. The West Fort fell as the sun was going down. Milroy pulled his men out and set them on the road to Harper's Ferry at about 10:00 PM.

Ewell had expected such a move, and had ordered a division under Major General Edward Johnson to cut off Milroy's line of retreat. The two forces ran into each other at about 3:30 AM at a bridge that ran across a deep railroad cut. Milroy's force was substantially larger than Johnson's, but Milroy was unable to coordinate an effective attack, while the Confederates took up good defensive positions in the railroad cut. They also set up a gun on the narrow bridge and repeatedly forced back Federal attacks with canister and grapeshot fired at point-blank range. Confederate gunners were shot, but enough volunteers came forward to keep the gun firing and the Union men at bay.

As the sun came up the next morning, a Confederate brigade under Brigadier General James Walker came up the road and threw themselves into the fight. Milroy's force dissolved, with the soldiers breaking and scattering. Many were captured. The Federals suffered 443 killed and wounded, as well as losing 3,358 men as prisoners. Ewell seized 23 guns and 300 wagons, with a loss of only 269 men.

On 15 June, Ewell's men began their crossing of the Potomac near Shepherdstown. The crossing was completed by 18 June. The next day, Ewell sent his lead division through the Cumberland Valley into Pennsylvania. The state appeared wide open. Ewell's general objective was the state capitol of Harrisburg, on the north bank of the Susquehanna River.

* Also on 15 June, Lee sent orders to Longstreet at Culpeper and A.P. Hill at Fredericksburg to put their men on the march and move fast. Lee himself was to follow in two days' time. The march was hot and dusty, many men fell out, and a few died.

On 16 June, Jeb Stuart's men mounted up to join the movement. Pleasonton's Union cavalry, encouraged by the good showing they made at Brandy Station, gave Stuart's troopers little peace as they moved toward the Blue Ridge Mountains. On the afternoon of 17 June, a Federal brigade under Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick met a smaller force of Stuart's cavalry under Colonel Thomas Munford near the village of Aldie, in the Loudon Valley. Kilpatrick sent his men in piecemeal and they were badly cut up. The outnumbered rebels stood their ground until about 7:00 PM, and then decided to retire.

Kilpatrick had been trying to link up with Colonel Alfred Duffie's 1st Rhode Island cavalry, but instead of finding Kilpatrick, Duffie ran into three brigades of Stuart's men. Duffie was surrounded and didn't manage to escape until early in the morning of 18 June, having lost over two-thirds of his 300 men in the process.

These skirmishes had gone badly for the Yankees, but they weren't in any mood to give up easily, and the clashes in the Loudon Valley continued. On 19 June, Stuart fought an all-day rearguard action against a division of Federal troopers under General David Gregg along a ridge west of Middleburg. Stuart was forced to withdraw to a further ridge. Stuart was so hard-pressed that even though Longstreet had brought his men into the Shenandoah Valley through Ashby's Gap and Snicker's Gap that day, Lee ordered him to move back into the mountains to back up Stuart.

There was no serious fighting in the Loudon Valley on 20 June because of heavy rains, but the shooting flared back up with a vengeance on the 21st. Stuart was forced back to Upperville and wild battles raged around the town. The fighting went on all day, with Stuart finally withdrawing through Ashby's Gap at about 6:00 PM.

Pleasonton's soldiers and horses were worn out by the five days of fighting and did not pursue. The final score was 613 Union casualties versus 510 Confederate casualties. In absolute numbers, the Federals had got the worst of it -- but not by so much, and not by more than they could afford. They hadn't been able to penetrate Stuart's screens, but they had kept him on the defensive and pressed him hard, and the Union cavalry were rightly proud of themselves.

Stuart understood that as well as the Federals did. Being roughed up by the Yankee cavalry he and his men had so long held in contempt was humiliating, even if he had given them a bloodying. He was also smarting from the criticisms the carping Southern newspapers had thrown at him for his bumbling at Brandy Station. The Richmond EXAMINER had pointed an accusatory finger at "vain and empty-headed officers", and other papers had been equally unkind. Stuart, who was indeed vain, burned to recover his reputation. Lee, who along with his other virtues was an excellent judge of character, knew that Stuart's pride might make him rash. Stuart wanted to ride off and harass Hooker's army, but Lee emphasized that the cavalry's proper place was to protect the western flank of the advancing Confederate forces.

Then, on 23 June, Lee suggested that Stuart might indeed be allowed to engage in an extended foray, but only under the condition that Hooker's army did not move north across the Potomac. If the Federals did move north, Stuart was to immediately take up guard on the Army of Northern Virginia's flank. Stuart was so excited about the prospect of further glory that the conditions stipulated by Lee carried little weight.

The next morning, 24 June, Stuart ordered his two largest brigades, under Beverly Robertson and Grumble Jones and totaling about 3,000 men, to stay behind and guard the Blue Ridge passes. He gave orders to his three best brigades, under Wade Hampton, Fitzhugh Lee, and Colonel John R. Chambliss (in brigade command in the absence of the wounded Rooney Lee) to accompany him on a raid. They left in the dark hours of 25 June -- and for all practical purposes, rode right out of the coming campaign.

By that time, Ewell's advance forces were over ten miles (16 kilometers) up the Cumberland Valley into Pennsylvania. Longstreet and A.P. Hill had begun their crossings of the Potomac at Shepherdstown and Williamsport on 24 June. The Confederates were now fully committed to their invasion of the North.

BACK_TO_TOP* Joe Hooker led the Army of the Potomac out of camp on 25 June, crossing the Potomac on 27 June. After crossing the river, however, Hooker and the Army of the Potomac went their separate ways.

Not long after Chancellorsville, President Lincoln, War Secretary Edwin Stanton, and General Henry Halleck -- the nominal commander of the US Army, though the officers under his command generally found him a useless, fussy, and obnoxious headquarters operator -- had agreed that Hooker wasn't fit to command an army, and should be sacked. To deflect public criticism, they decided to wait for the volatile Hooker to offer his resignation, and they were doing much to encourage him to do so. Halleck and the War Office had been badgering him incessantly since Lee began his move north, simultaneously pushing him to take action while imposing conditions on what actions he could take. Following a dispute with Halleck over the disposition of troops near Harper's Ferry, Hooker submitted his resignation on the afternoon of 27 June. Halleck replied, disingenuously, that it had to go to the President for approval.

In fact, a Colonel James A. Hardie had left Washington by train even before Halleck sent that reply. Hardie's mission was to find Major General George Gordon Meade and inform him that he was to lead the Army of the Potomac. In the dark hours of the morning of 28 June, Hardie awakened Meade to tell him the news. Meade, punchy with sleep, at first thought he was being arrested. Hardie compounded Meade's confusion by saying: "General, I've come to make trouble for you."

When Meade found out that he was being given command of the Army of the Potomac, he wasn't much happier. He tried to turn it down, suggesting that other officers, particularly John Reynolds or John Sedgwick, were better qualified, and in fact technically senior to him. As with Burnside before him, Meade was told that the assignment was an order, not a request. Meade abandoned his protests and replied: "Well, I've been tried and condemned without a hearing, and I suppose I shall have to go to execution."

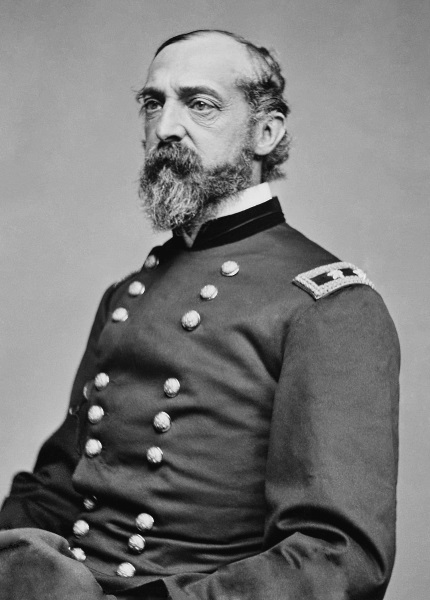

Meade was then 47 years old. He was a West Pointer who had served in the Mexican War; he was competent, intelligent, coolly courageous under fire, and neither given to self-promotion nor political partisanship. He wasn't particularly impressive in appearance, being a tall skinny man with a balding head and glasses, and in fact he tended to be quiet and bookish. However, his quiet demeanor concealed an explosive temper. His troops called him an "old goggle-eyed snapping turtle"; he both knew it and accepted it. He was not what anyone would call a natural leader of men.

Hardie took Meade to Hooker's tent. Hooker had no specific advance warning of the change in command, though considering how often the Army of the Potomac changed hands he couldn't have been too surprised. Meade wrote his wife that Hooker had no trouble with the transfer, saying of his command that "he had enough of it, and almost wished he had never been born." Hooker was very cooperative and generally pleasant about the matter.

However, Hooker didn't have much in the way of a battle plan to hand to Meade, and Meade didn't even have a clear idea of where all the Army of the Potomac was. Fortunately, the instructions Halleck provided in the order promoting Meade to command were surprisingly loose. Meade had a free hand to do what he pleased, as long as he followed the stipulations to shield Washington and Baltimore, and to bring the enemy to battle. Halleck wrote: "You will not be hampered by any minute instructions from these headquarters."

John Reynolds and John Sedgwick dropped by to offer their congratulations and promise their support, which reassured Meade, who had feared they might be resentful at being passed over. In fact, Reynolds had gone to Washington a few weeks earlier to make it clear to the authorities that he did not want command of the Army of the Potomac, unless he was free from political interference in his decisions. Reynolds had no reason to feel that he had been badly treated in not having been given the top job. Sedgwick had more reason for complaint, and in fact at first he seemed to take the news badly, but he was a level-headed man and got over it quickly.

Meade threw himself into his work, and in the afternoon of 28 June he telegraphed Halleck:

I MUST MOVE TOWARDS THE SUSQUEHANNA, KEEPING WASHINGTON AND BALTIMORE WELL COVERED, AND IF THE ENEMY IS CHECKED IN HIS ATTEMPT TO CROSS THE SUSQUEHANNA, OR IF HE TURNS TOWARD BALTIMORE, GIVE HIM BATTLE.

On the morning of 29 June, the Army of the Potomac moved out and marched north towards the Pennsylvania border. Intelligence reported that the corps of A.P. Hill and Longstreet were camped near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, and so Meade ordered Dan Sickles' III Corps, John Reynolds' I Corps, and Oliver Howard's XI Corps to concentrate near Emmitsburg, Maryland, just below the Pennsylvania border, to meet the threat.

Meade urged haste, telling Reynolds "strong exertions are required." George McClellan had never done things in a hurry, always worried about being massively outnumbered by the Confederates. Meade had much less of "the slows" than McClellan, and also had a much better grasp of realities. Meade's intelligence suggested that Lee's rebel force numbered 80,000 and had 275 guns, which was within a few thousand men and a handful of guns of the truth.

Despite the past history of humiliations, the Army of the Potomac marched back onto Union soil with a general sense of enthusiasm and confidence. Northern Virginia had been badly trashed by the back-and-forth movements of armies, and the Virginians regarded Northern soldiers with the hatred earned by an invader. North of the Potomac, the land was green and prosperous, and the people generally glad to see them -- though that did not restrain some inconsiderate Union soldiers from their accustomed habits of looting.

The soldiers were looking forward to a fight. One officer wrote: "They are used to being whipped, and no longer mind it. Some day or other we shall have our turn." They felt this was going to be it, one soldier saying: "We felt some doubt about whether it was ever going to be our fortune to win a victory in Virginia, but no one admitted the possibility of a defeat north of the Potomac." A surgeon wrote of the troops: "They are more determined than I have ever before seen them."

John Buford's cavalry division rode ahead of the Union columns, probing for the Confederates. At midmorning on 30 June 1863, the troopers rode into the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, which was east of Chambersburg and north of Emmitsburg, where the citizens told them that a Confederate infantry brigade had just come and gone.

* Lee's columns had moved north into Pennsylvania with their usual swiftness. Dick Ewell had divided his II Corps into three parts to advance over a wide front, with Ewell accompanying the main column, which consisted of two brigades and a division under Major General Robert Rhodes moving towards the Susquehanna and Harrisburg through the towns of Carlisle and Mechanicsburg. A brigade foraged in parallel to the west, while Jubal Early's division headed east to make a crossing of the Susquehanna downstream at Wrightsville, allowing the rebels to attack Harrisburg from two sides.

Early's division had to go through the towns of Gettysburg and York to get to Wrightsville, and the Confederates came into Gettysburg late in the afternoon of 26 June, with Pennsylvania militiamen prudently fleeing ahead of them. Early commented dryly: "It was well that the regiment took to their heels so quickly, or some of its members might have been hurt."

The citizens of Gettysburg found the rebels "exceedingly dirty, some ragged", but observed their "perfect discipline". Early demanded supplies from the townspeople but they had hidden away most of their goods, and the Confederates were in too much of a hurry to insist.

Early's men reached York on the evening of 27 June and Wrightsville the next day -- only to find out that the long covered bridge that went over the Susquehanna from that town had been burned. Early pulled back to York to await instructions from Ewell.

* In the meantime, Ewell's main column had marched through Carlisle on 27 June, and by the next day his advance cavalry was camped on a hill just south of the Susquehanna and Harrisburg. Harrisburg seemed wide open and defenseless. However, that same night, a ragged Confederate spy who had been sent north by Longstreet and remains known to history only as Harrison showed up at Lee's headquarters. Harrison reported the Union Army of the Potomac was on the move, and that he had seen two corps camped near Frederick, Maryland, and Federal columns moving towards South Mountain to fall on Lee's supply lines.

He also informed Lee that Meade had replaced Hooker. Some time later, a few of Lee's officers commented that Lincoln had yet again given command to an officer who would be no match for their own superlative leader -- but Lee had known Meade well in the old Army, and did not agree: "General Meade will commit no blunder on my front, and if I make one he will make haste to take advantage of it."

Lee had no great confidence in spies and scouts, but Longstreet vouched for Harrison's reliability; with Stuart nowhere to be found, Lee had no better sources of intelligence. The next morning, Lee ordered Ewell to pull all his forces south and concentrate to the west of Gettysburg for battle. The rebel cavalrymen just south of Harrisburg had gone as far north as the Army of Northern Virginia would get during the entire war.

Longstreet and A.P. Hill were ordered to lead their corps to the area near Gettysburg as well. On 30 June, a Confederate infantry brigade under Brigadier General James Johnston Pettigrew -- part of Henry Heth's division in A.P. Hill's corps -- marched on Gettysburg. Heth claimed in his memoirs that they were following up a report about a shoe factory there, obviously a desireable target for footsore Confederates. However, not only did no one else recall this item, there was no shoe factory in Gettysburg. The story about the "shoe factory" became one of the enduring myths of the battle, often being recounted in histories of the event; but it appears to have been a mis-remembering, or puzzling fabrication, by Heth.

In any case, the rebel brigade got there just in time to see Buford's cavalry approach the town. Pettigrew had no mandate to start a fight, didn't want to bite off on what might be more than a brigade of infantry could deal with on their own, and so he ordered his men to withdraw a few miles away from the town. They planned to return the next day, once more back-up was available.

John Buford knew there would be a big fight. One of his brigadiers suggested that the enemy wouldn't return, and if they did, they would be easily driven off. Buford, a deceptively easy-going Kentuckian who was all fighter under the surface, replied: "No, you won't. They will attack you in the morning and they will come booming, skirmishers three deep. You will have to fight like the devil before support arrives."

BACK_TO_TOP