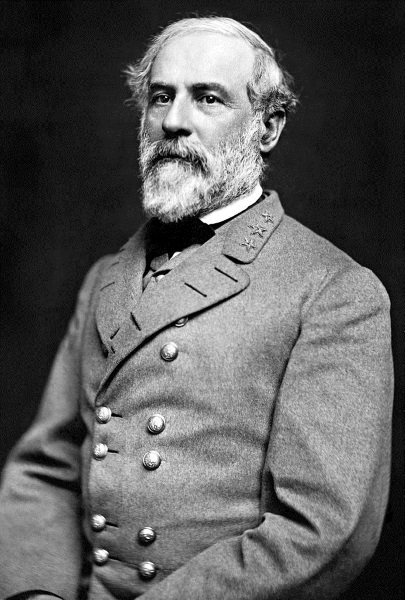

* Lee's Army of Northern Virginia had dealt the Union Army a painful blow at Bull Run. The immediate result was that McClellan's authority was restored, and he competently worked to get his forces back in order. Lee was soon moving north into Maryland, with the Army of the Potomac marching, cautiously, to confront him.

* On Tuesday, 2 September 1862, the full impact of the second Union defeat at Bull Run became obvious as stragglers drifted into Washington. They were ragged, shoeless, and had little to eat for days. A column of pathetic wounded men was trickling in as well. Some order was made of the confusion, and the seized carriages and cabs and carts were organized into trains to ferry supplies and the injured to their proper destinations.

With a rebel army on the prowl, panic began to grow. Secretary Stanton had given orders to move the contents of the city's arsenal to New York City so that the weapons and ammunition would not fall into Confederate hands, and War Department papers were being bundled up so they could be removed quickly. The sale of liquor had been prohibited; government clerks were being armed and formed up into companies; Union gunboats were anchored in the Potomac; and Stanton had a steamer standing by to evacuate the President and other Administration officials, if it came to that.

The torrential rainfall that had doused the combatants at Chantilly the afternoon before had left puddles ankle-deep in the streets, but the skies were sunny that morning when Lincoln and General Halleck came to General McClellan's house. There the President asked McClellan to take charge of the city and the scattered soldiers falling back into it.

It happened just as McClellan had foreseen: "Bien." But it wasn't good. Lincoln had, like many others, come to the conclusion that McClellan had wanted Pope to fail. Reinforcements had been sent forward in a way that seemed indifferent at best, and the President had hardly forgotten McClellan's astonishingly thick remark about leaving Pope "to get out of his scrape" as best he could. McClellan's resurrection hadn't just "happened"; McClellan had done much to make it happen.

In fact, McClellan had been maneuvering for position even as Pope's fall was in progress. He had wired Halleck on 31 August:

I AM READY TO AFFORD YOU ANY ASSISTANCE IN MY POWER, BUT YOU WILL READILY PERCEIVE HOW DIFFICULT AN UNDEFINED POSITION, SUCH AS I NOW HOLD, MUST BE. AT WHAT HOUR IN THE MORNING CAN I SEE YOU ALONE, EITHER AT YOUR OWN HOUSE OR THE OFFICE?

When the full dimensions of the disaster became apparent, Halleck replied:

I BEG YOU TO ASSIST ME IN THIS CRISIS WITH YOUR ABILITY AND EXPERIENCE. I AM UTTERLY TIRED OUT.

John Hay perceived that the President thought McClellan a little crazy, but there was simply no alternative to him for the moment. Pope was as defeated as his army, the wind had been completely knocked out of him, and whatever hopes Lincoln had placed in Halleck had been proven false. Lincoln would describe Halleck to John Hay as "little more than a first-rate clerk." The President said of McClellan: "We must use the tools we have. There is no man in the Army who can man these fortifications and lick these troops into shape half as well as he ... if he can't fight himself, he excels in making others ready to fight." If McClellan had made the Army of the Potomac to a degree his personal instrument, an unacceptable situation for the Commander-in-Chief, that fact alone made McClellan indispensable in the current crisis.

Lincoln had made the decision on his own, and only after it was done did he announce it to his cabinet. Stanton was shocked. He had been petitioning the other cabinet members to push through an ultimatum demanding that McClellan be permanently removed from any authority; Stanton was expecting to court-martial McClellan, not re-instate him to command. Stanton said, trembling: "No order to that effect has been issued from the War Department." Lincoln replied: "The order is mine, and I will be responsible for it to the country." Chase proclaimed that restoring the general was "equivalent to giving Washington to the rebels." Montgomery Blair said that Stanton and Chase would have preferred the loss of Washington to the re-instatement of McClellan.

That afternoon, McClellan and some of his staff rode down the road to Centerville towards the battleground as soldiers drifted back up the road toward him. He halted them and ordered them to fall into ranks. Soon he encountered a cavalry regiment, with Pope and McDowell "sandwiched in their midst", as McClellan put it. The defeated generals were tired, dirty, and demoralized. McClellan said: "I never saw a more helpless-looking headquarters." He rode up to them, erect on his big black horse, dapper with a yellow sash around his waist, snapped off a salute to them, and informed them he had been put in charge of the army.

Suddenly there was a dull thump of artillery on the horizon. McClellan asked: "What was that?" Pope suggested it was an attack on troops guarding their flank, and asked if General McClellan would mind if he -- Pope -- and McDowell rode off to Washington? McClellan replied, almost cheerfully: "Not at all, but for myself I am going to ride to the sound of the firing and see what is going on in the way of fighting." McClellan would have been scarcely human had he not wanted to gloat a little.

There were others in the crowd who didn't want to stop at a little gloating. General Hatch, who had been relieved of duty north of Gordonsville at the beginning of the whole campaign, had been put in charge of Rufus King's division, King having fallen onto the sicklist. Hatch had ridden up to listen in on this exchange, and, feeling he had a score to settle with Pope, shouted out loud: "Boys, McClellan is in command of the army again! Three cheers!"

There was a moment's confusion as the words soaked in, and then like a slow wave the cheering started, rising into mass frenzy. The soldiers, their burdens lifted for the moment, threw their caps and knapsacks into the air, embraced each other with joy, shouted themselves hoarse. The news filtered back along the column with the same electrical results, men instantly restored to excitement after the crushing experience they had been through: McClellan had returned.

* In the meantime, Halleck had issued the formal order giving McClellan the reins: "Major General McClellan will have command of the fortifications of Washington and of all the troops for the defense of the capital." Pope's Army of Virginia was no more, and his corps were now incorporated into the Army of the Potomac. The next day, Wednesday, 3 September, the President ordered Halleck to prepare the army for active operations, and Halleck passed the word on to McClellan.

McClellan quickly moved to put things in order. Whatever his other limitations, his efficiency and managerial skill were beyond any serious dispute. The streets and saloons and whorehouses were milling with demoralized soldiers; they were rounded up and sent back to duty, and those who were too hopeless or had no organization left to report to were sent to an improvised "convalescent camp" in Alexandria. The camp was little more than a dumping ground for the army's misfits, but at least it got them off the streets.

The wounded were attended to as well as could be managed. They drifted back during the week, often in very sad condition. Hundreds had spent a rainy and miserable night lying in straw in a field around Fairfax Court House, attended to by a handful of doctors and a few earnest nurses. More carriages were seized on the street to provide transportation for the wounded. The Prussian ambassador was left standing on the street when his carriage was taken from him; Secretary of State Seward quickly put safeguards in place to keep such insults from happening again. An enlisted man even tried to take the President's barouche from him, only to be stopped by a horrified sergeant. Lincoln replied that the man was only doing his duty.

McClellan seemed to work miracles, though in fact the blow the army had taken at Bull Run, though very painful, was far from mortal. The men were just disorganized, and they were collectively soldiers enough to seek organization if there was someone credible in charge to provide it. On Thursday, 4 September, McClellan sent out advance units to find the enemy, who were now believed to be moving north. On Friday, 5 September, the army marched, six corps, 84,000 strong, to intercept the Confederates who had been reported moving north towards Maryland.

The demoralized soldiers cluttering the streets into the week had left a bad impression on the citizens that would not easily be dispelled, but the townsfolk were impressed as the Army of the Potomac came marching through the town, in prefect order, well-drilled and equipped for battle. Their weapons and kit and uniforms were worn by service in the field, and the shiny gleam that they had a year before was gone, but in its place was a core of resolve. Significantly, they were not marched past the White House; instead, they were routed past McClellan's house, where they issued great cheers for their commander. Two corps, under Sigel and Major General Samuel P. Heintzelman, were left behind under the command of Nathaniel Banks to defend Washington. The next evening citizens were startled to see soldiers resting on the White House lawn, with the President moving among them, serving them water with a pail and dipper.

While the army marched, the administration considered what to do with the losers. Pope got a dispatch on Friday, 5 September: "The Armies of the Potomac and Virginia being consolidated, you will report for orders to the Secretary of War." Pope's vision had been imperfect; he had indeed unified his and McClellan's commands, but now McClellan was in charge. Pope reported, and was immediately ordered to go to the Northwest and suppress the Indian uprising there. He would be in Saint Paul before the month was out, effectively removed from the real war for the duration, though he would prove effective in suppressing the tribes. McDowell was cleared of all the accusations thrown at him -- he'd been accused not just of treason, but also drunkenness, when his hatred of demon liquor was well-known -- but he never got a combat command again, since nobody wanted to serve under him.

The Army of the Potomac was marching to battle, but officially they had no leader at the head of their columns. McClellan's orders had only specified command of the defenses of Washington. That was mere bureaucracy, however, and in fact McClellan was still the commander of the Army of the Potomac; after all, no order had been issued relieving him. Field command had been offered to Burnside, who had energetically refused it, and there was no other choice. Halleck and Lincoln engaged in an odd game of finger-pointing as to who would give the order putting McClellan in charge, with the end result that McClellan never got an official order at all. He went ahead with what instructions he had, though he believed that if the Army of the Potomac were defeated he would be held responsible, possibly even hanged. Given some of the hysteria in high places, it is hard to say that McClellan was being silly.

That Sunday evening, 7 September, Navy Secretary Gideon Welles and his son Edgar were walking the streets of the town, when they were passed by McClellan and his staff. Welles saluted McClellan, and McClellan pulled his horse over to the sidewalk to give his respects. Welles asked where they were going. McClellan replied that they were off to take command of the forces marching from the city. Welles was no great admirer of McClellan, but was not inclined to the petty: "Well, onward, General, is now the word; the country will expect you to go forward." McClellan replied that was his intention.

Welles, an honest man, replied sincerely: "Success to you, then, General, with all my heart." Although the injuries, both imagined and very real, McClellan had received in the past from his political superiors could hardly be forgotten, he left the city with a blessing that he might desperately need.

BACK_TO_TOP* Lee had written Confederate President Jefferson Davis on Wednesday, 3 September, from Chantilly, opening his message with: "The present seems to be the most propitious time since the commencement of the war for the Confederate Army to enter Maryland." His reasoning was of logic and necessity, as it had been through the summer. His forces were worn and tattered by the victories they had won, short on food, clothing, ammunition and other supplies, but the Army of Northern Virginia faced three difficult choices: they could either withdraw; stay where they were; or go North.

While withdrawing would allow Lee to rest and refit his exhausted soldiers, it would also abandon the initiative obtained in the last week, and it was just as obvious to Lee then as it had been earlier that time worked for the Union army, not the rebels. Given time, the Federals would mass in such strength that the Confederacy would be certainly doomed.

Staying where they were wasn't an option, either. Again, it would abandon the initiative to the Federals, and besides, there were no supplies or provisions available in the area, which had been picked clean by marauding armies.

That only left the offensive. Washington was a desireable but impossible target. The defenses were extensive and well-constructed, and the Army of the Potomac was there in force to man them. McClellan could not have conceived of anything more convenient to the Federal cause than for Lee to attack Washington. However, with the Army of the Potomac in a disorganized state, Maryland was wide open. Even if Lee could not defeat the Federals in battle, such a movement would have many benefits. He could obtain food and forage from the Maryland countryside; by putting the Yankees on the defensive, he could forestall another advance on Richmond before the winter set in, buying time for the Confederacy, and also allow Virginians to get their crops in unmolested. Lee wrote: "We cannot afford to be idle, and though weaker than our opponents in men and military equipments, must endeavor to harass them if we cannot destroy them."

Furthermore, many Marylanders were fighting in the Army of Northern Virginia, and a Confederate presence in the state might attract thousands of badly-needed recruits. The shock of the invasion would also increase war weariness in the North, as well as improve the prospects of foreign recognition. The rebel victories since the end of June were receiving considerable publicity in Great Britain and France, and a successful campaign on Northern soil might just convince them that the Confederacy was a going proposition.

On 4 September, Lee sent a telegram to Jefferson Davis explaining that he intended to proceed, and without waiting for approval put the Army of Northern Virginia on the march northward, moving to the town of Leesburg and then beyond to White's Ford, where the Potomac cut through mountains and his men could walk across the river. The first units made it there on Thursday, 6 September 1862. The rebels continued their crossing for three more days.

Roughly 50,000 men made the crossing. While Lee had received about 20,000 reinforcements from Richmond, he lost about 15,000 from straggling and desertion. Many of his men were sick, exhausted, and could not keep up; some of the soldiers from northern Virginia found the proximity of their homes too much to be resisted; and some North and South Carolinans, fighting against the injustice of aggression against their own home states, wanted no part of an invasion of another. The men who remained were the hard core. They would stand and fight even against terrible odds. One wrote his family: "None but heroes are left."

* The Confederates assembled near Frederick, Maryland, about 50 miles (80 kilometers) northwest of Washington. The enthusiastic reception they had expected from Marylanders didn't materialize. Confederate sympathy was strong in Baltimore and the tidewater regions of the state, but farther inland the temperament was Unionist, and only a few sympathizers waved little Confederate flags. Some of the citizens set out buckets of water or even gave up their shoes, but these were more acts of sympathy for the raggediness of Lee's men than for their cause. In one small town, a rebel soldier noted that "the houses were all shut up & nearly all the people we saw looked as though they had lost a dear friend."

A loyalist woman wrote of the Confederates: "I asked myself in amazement, were these dirty, lank, ugly specimens of humanity the men that had driven back again and again our splendid legions with their fine discipline, their martial show and colour? I felt humiliated at the thought that this horde of ragamuffins could set our grand army of the Union at defiance. Oh! They are so dirty!

I don't think the Potomac River could wash them clean!" A Maryland boy said much the same: "They were the dirtiest men I ever saw, a most ragged, lean and hungry set of wolves." But he could not help adding: "Yet there was dash about them that the northern men lacked. They rode like circus riders. Many of them were from the far South and spoke a dialect I could scarcely understand. They were profane beyond belief and talked incessantly."

They were dirty, but their rifles were clean and their cartridge boxes full. They were shoeless, ragged, half-starved, ill, but still tough, smart fighters. Alfred Waud, a war artist from HARPER'S WEEKLY, was in the custody of Jeb Stuart's cavalry troopers for a short time, and described them as homely in dress but well-equipped, carrying carbines "mostly captured from our own cavalry, for whom they expressed utter contempt."

Their leaders were fighters as well, but they had been having a peculiar spell of bad luck. On 31 August, while the rain was pouring down and the Federals were in retreat from Manassas, Lee had been standing by his horse, Traveler, when a cry came up: "Yankee cavalry!" The horse had been startled, Lee had turned to grab the reins, then tripped and fell in his clumsy rain gear. He broke a bone in one hand and badly sprained the other. Lee rode north in an ambulance, with both hands in bandages. Stonewall Jackson ended up in an ambulance as well. After crossing the Potomac, some friendly Marylanders had given him a big gray mare that threw him, giving him a painful back injury. Longstreet was hobbling around wearing a carpet slipper, having obtained a big blister on his heel.

John Bell Hood and A.P. Hill were having problems of a different sort: they were both under arrest. Hood got into a dispute with Brigadier General Robert Toombs -- a politician in uniform, one of the founders of the Confederacy, who had gone into the army after falling out in the government. The two men had a difference of opinion over which deserved a set of captured Yankee ambulance wagons; Hood was ordered to give the ambulances to Toombs, but the Texan pig-headedly refused to obey the order. Longstreet relieved him of command pending a court-martial, but Lee ordered Hood to accompany his division anyway.

Stonewall Jackson was also still on A.P. Hill's back, and when Jackson interfered with the march of Hill's division, Hill angrily offered to resign on the spot. Jackson told him he was under arrest. It seemed the Army of Northern Virginia was marching North with a hand tied behind its back.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Confederates tried to charm the Marylanders as best they could. Lee wrote up a proclamation inviting them to add their strength to the Confederate cause, and Stuart staged a ball on Monday the 8th in a deserted school building, only to dash off to repel a Federal probe, then to return with stories of adventure for the pretty young ladies present. There was little public response to either measure, and he knew he had to move on anyway.

As usual, Lee was thinking big. His clear immediate target was Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, near the Susquehanna River. A key bridge of the Pennsylvania Railroad ran over that river; destroying that bridge would effectively cut the Union in two -- reinforcements from the West would not be able to reach the East by rail except by the most roundabout route. That done, he could attack Philadelphia, Baltimore, or other vulnerable cities in the North. With a rebel army rampaging through the streets, the Union might well be forced to sue for peace.

The only problem he could see was that there were two Federal forces in a position to threaten his supply line to the south: 12,000 Federals in occupation of Harper's Ferry, 16 miles (26 kilometers) away, and 2,500 Yankees at Martinsburg, about 10 miles (16 kilometers) farther west along the railroad line beyond Harper's Ferry. Lee had assumed these two garrisons would be evacuated immediately once he moved north, but the War Department had perversely told them to hold their ground, even though McClellan recognized their vulnerability and had pleaded for them to be withdrawn. Lee would have to eliminate these garrisons before the big push north could take place.

McClellan's concern over the vulnerability of the garrisons was well founded. The force at Martinsburg was too small to put up effective resistance, and Harper's Ferry was all but indefensible. There were heights on all sides of the town except the southwest: Maryland Heights above the Potomac to the northeast, Loudoun Heights across the Shenandoah to the southeast, and Bolivar Heights to the northwest.

Lee had been having such good luck in dividing his forces that he decided to do it again. Jackson, who had by now recovered from his back injury, was to lead three divisions in a roundabout route well up the Potomac, march them across the river, capture or drive out the garrison at Martinsburg, and then occupy Bolivar Heights. Major General Lafayette McLaws would take two divisions by the direct route to Maryland Heights, and Brigadier General John G. Walker would similarly move directly to Loudoun Heights. The Federal garrison in Harper's Ferry would then be effectively surrounded and have to surrender.

Longstreet was strongly opposed to the plan. They had got away with dividing their army once in the face of a stronger force, but doing it in the enemy's back yard was pushing their luck. Jackson, on the other hand, was enthusiastic, and in any case, boxing in the Yankees at Harper's Ferry made the separation of forces unavoidable. Lee set the plan in motion by issuing "Special Order 191" on 9 September, instructing the various commands in their movements.

Lee was, for the moment, not highly concerned about superior enemy forces in the vicinity, despite the fact that the newspapers revealed McClellan was back in command, and Stuart had observed the Federals on the march towards Frederick. When Walker expressed astonishment at the risks Lee was taking, Lee replied that McClellan was "an able general, but a very cautious one. His enemies among his own people think him too much so. His army is in a very demoralized and chaotic condition, and will not be prepared for offensive operations, or he will not think it so, for three or four weeks. Before that time I hope to be on the Susquehanna."

Special Order 191 pinpointed the locations of the different elements of the commands for the next several days, and the order was handled carefully by its recipients. Jackson personally copied the order and had it sent to Major General Daniel Harvey "D.H." Hill -- yet another hot-headed Confederate front-line commander, noted for his particularly acid hatred of Yankees -- who read it and locked it away. What neither man knew was that Hill had also been sent an official copy of the same order. It never got to him. Through some sequence of steps that remains a total mystery, it ended up in the pocket of an anonymous staff officer, who used it to wrap three cigars.

* On Wednesday, 10 September, Lee's army marched through the streets of Frederick on the way to their objectives. People lined the streets, with young women waving flags, both Union and Confederate. One buxom young lady had the Stars & Stripes pinned to her dress, causing a witty Louisiana soldier to call out: "Look h'yar, miss, better take that flag down -- we're awful fond of charging breastworks!" His fellows laughed. The girl blushed and smiled.

Brigadier General Howell Cobb of Longstreet's command -- another one of the Confederacy's founding fathers -- was recognized by Unionists and loudly jeered. He returned the compliments, threatening to come back after they beat McClellan and put the Unionists in jail. Simply trading insults was not his style, however; he was a stump politician, and when he came upon a young girl waving a rebel flag, he used it as an occasion to deliver an impromptu speech in praise of the Confederate cause that had the crowd applauding him with amusement.

The Confederate occupation of Frederick did lead to one odd matter of consequence. According to one version of the story, a small child ran into the house of 95-year-old Barbara Frietchie and shouted: "Look out for your flag, the troops are coming!" Thinking the child meant Union soldiers, she ran to the door and began waving a small American flag; when the soldiers started cat-calling her, she realized her error, but kept on waving it anyway. The soldiers were annoyed and let her know, but a Confederate officer simply told Frietchie: "Go on, Granny, wave your flag as much as you please."

The woman became a local heroine for this little incident, and then the story spread and grew in the telling, to the point where the New England poet John Greenleaf Whittier wrote a poem glorifying how Frietchie had personally defied Stonewall Jackson at the risk of her life:

"Shoot, if you must, this old gray head, But spare your country's flag," she said.

It was all overblown nonsense, of course. According to another story, she had simply waved the flag at McClellan's troops arriving two days later. Confederate papers complained, but it became one of the enduring petty legends of the war.

Inflated stories were only to be expected. Rumor and hysteria were running wild in the North. Halleck had forbidden reporters to travel with the Army of the Potomac; although enterprising newspapermen proved clever at evading the ban, aided at times by publicity-hungry generals, the newsmen did not have access to military telegraphs, and the War Department itself wasn't saying anything. In the absence of any real news, there was nothing to restrain public fears.

Baltimore was in something of an uproar. The city's secessionists, long suppressed by Federal authority, were excited at the prospect of liberation, but the place was under the military jurisdiction of Major General John Wool, then in his late seventies. Though Wool might be a little shaky he was still full of fight, and would defend the city for the Union from threats within and without using every means at his disposal.

In contrast, Philadelphia was completely defenseless, and the citizens there were extremely agitated. There was nothing Lincoln could do but reassure them, telling them that the rebels were far away, and that the best thing to do was to seek out Lee's army and attack it -- not send troops to protect every nervous township.

Pennsylvania Governor Andrew G. Curtin was busily calling up the state militia and doing everything he could to prepare for a Confederate invasion. Pennsylvania had a lot of regiments in the Army of the Potomac, so Curtin was owed a lot of favors in Washington. He had called them in, and to keep him happy Halleck sent, over the objections of General McClellan, Brigadier General John Reynolds, a Pennsylvanian, to Harrisburg to direct the defense of the state for its government.

* Lee was completely mistaken in believing that the Army of the Potomac was in a chaotic and demoralized condition; it was neither. Under McClellan's leadership, the army had reformed its ranks rapidly and was in good fighting trim. Lee's estimate of McClellan's cautiousness was perfectly accurate, however. McClellan had been advancing slowly, marching not much more than 6 miles (10 kilometers) a day, and by Thursday, 11 September, his army was no closer than 15 miles (24 kilometers) to Frederick.

Much of the problem was a lack of military intelligence; McClellan's considerable talents always dried up when it came to determining the strength and intent of an adversary. Stuart's troopers had been easily frustrating the clumsy Union cavalry, and McClellan didn't even know the rebels had been in Frederick until after they had left. McClellan characteristically estimated the strength of Lee's invasion force at around 120,000.

However, by this time, skepticism about such figures was becoming widespread. On 8 September, the NEW YORK TRIBUNE ran an article entitled "A Glimpse Behind Enemy Lines" by a commonsense reporter who had interrogated rebel prisoners and Union men who had been paroled -- in simple terms, released by the Confederates on the agreement that they would not be returned to the fight -- to build his own estimates. The reporter concluded: "The enemy has had no more men, not so much ordnance, nor provisions, nor nearly so much encumbering baggage but he has outgeneraled us ... this is the plain, unvarnished truth: we have been whipped by an inferior force of inferior men, better handled than our own."

Other newspapers still took the inflated figures at face value. McClellan never doubted, would never doubt, he was greatly outnumbered, and as usual was calling for reinforcements. Halleck was also sending him messages warning him that the rebel move was possibly a feint, intended to draw off the Army of the Potomac to allow an attack on Washington. Given that there were tens of thousands of troops still in the city under Banks and the place was well-fortified, it is hard to understand why Halleck was so alarmed, except for the fact that he was Halleck.

McClellan did feel obligated to ensure that Washington was properly protected, so his forces advanced in three wings to cover the city: a center wing under Major General Edwin Vose "Bull" Sumner moving directly towards Frederick, a southern wing under Major General William B. Franklin moving along the Maryland shore of the Potomac, and a northern wing under Major General Burnside moving along the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad.

The soldiers were enjoying the leisurely march, as the weather was splendid and the country pleasant. The Unionist locals greeted the soldiers warmly and gave them gifts of food and drink. The foraging was also good. A regimental colonel told a lieutenant on no account "let two of your men go out and get one of those sheep for supper!" The lieutenant replied: "No sir!" -- but their diligence went for nothing; the soldiers had mutton stew for dinner that night anyway. The top brass vigorously discouraged such thievery and in many cases the soldiers paid for what they took, since they had accrued pay during their months on the Peninsula and weren't hurting for cash. Unfortunately, the temptations were many, the obstacles few, and the Marylanders found the Federal soldiers worse thieves than the Confederates.

* On the evening of Thursday, 11 September, McClellan finally got reliable word that Lee had departed from Frederick, and ordered Burnside to get his soldiers there quickly. An advance unit approached the town on the morning of Friday the 12th, to encounter a rear guard of rebel cavalry under Wade Hampton. The Federals drove them back into Frederick, but Union cavalry pursued them a little too closely, were bloodied, and lost some men as prisoners, including the commander of the cavalry detachment, Colonel Augustus Moor. The Confederates then pulled out completely in the face of Yankee infantry moving into the streets of the town.

No sooner had the shooting died away than the townspeople materialized to greet the Union soldiers warmly, waving flags and giving them food. When McClellan himself rode into Frederick on his horse Dan Webster at about 9:00 AM the next morning, Saturday 13 September, he was mobbed: women gave him their babies to kiss, hugged his horse (someone tied a little American flag to the bridle), kissed his uniform, decked both man and horse in flowers. He wrote his wife that they "nearly pulled me to pieces."

Then, an hour later, McClellan received a gift far beyond that of his glorious entrance into Frederick. Earlier that morning, the men of the 27th Indiana were resting in a field that by all appearances had been a rebel camp a few days earlier. Two soldiers, Sergeant John M. Bloss and Corporal Barton W. Mitchell, were sitting there idly when Mitchell spotted something in the grass. It turned out to be three cigars wrapped in a sheet of paper. The paper bore the heading: "Special Orders No 191, Headquarters, Army of Northern Virginia." The startled soldiers quickly sent the document up the chain of command, where the division adjutant general, Samuel E. Pittman, confirmed the handwriting to be that of Lee's adjutant general, Robert H. Chilton; Pittman and Chilton had been comrades before the war.

Pittman dashed off to McClellan's headquarters, where he encountered the general in a meeting with local businessmen. McClellan politely dismissed the civilians, took the letter, and then read it with rising excitement. "Now I know what to do!" he cried out when he was finished. The rebel army was scattered before him in fragments. He could fall on each fragment, and destroy them one by one. He said to John Gibbon, who had just dropped in: "Here is a paper with which if I cannot whip Bobby Lee, I will be willing to go home."

Lincoln had just sent him a telegram:

HOW DOES IT LOOK NOW?

At noon, McClellan sent back an effusive response:

I THINK LEE HAS MADE A GROSS MISTAKE ... I HAVE ALL THE PLANS OF THE REBELS AND WILL CATCH THEM IN THEIR OWN TRAP ... WILL SEND YOU TROPHIES.

McClellan was on the upswing, all the more so because he had been depressed over his difficult political position. He believed the President had no faith in him, but if he could destroy Lee's army and effectively win the war, what the President thought would not matter very much.

McClellan was correct in his judgement of Lincoln. While the general did not know that it was the President who had restored him to command over the objections of some of his cabinet, the President did it out of convenience only. He told John Hay: "McClellan is working like a beaver. He seems to be aroused to doing something after the snubbing he got last week." Then the President added: "I am of the opinion that this public feeling against him will make it expedient to take important command from him ... but he is too useful now to sacrifice."

The President had once said that he would hold McClellan's horse if the general could bring him victories, but it was only the victories that counted, and McClellan was otherwise expendable. Lincoln was a civil and conscientious man, even to a degree a humble one, but he had a subtle will of steel with a cool and ruthless edge. He would do what he had to do to defeat the Confederacy and restore the Union, and McClellan was merely a useful, if imperfect, tool to that end.

* It was never discovered who had lost Special Order 191 and the three cigars. If he lived out the war, he decided that it would be unwise to come forward. Some speculated that it was the work of a traitor, but that seems unlikely; simply leaving the order in a field and hoping someone would find it would have been a most impractical scheme for passing on information to an enemy.

Special Order 191 told McClellan that Lee's command had been broken into four parts. In fact, Lee had been forced to change his plans slightly. Reports had reached Lee on 10 September that the Federals were advancing from Pennsylvania towards Hagerstown to the north. He moved to that town with Longstreet and 10,000 men, leaving D.H. Hill in Boonsboro, up the road from Frederick, with 5,000 men. Lee's army was actually in five parts, not four.

The advance element of the Confederate force intended to capture Harper's Ferry, consisting of 8,000 men under Lafayette McLaws, had made camp on the evening of 11 September about 6 miles (10 kilometers) northeast of that place. The next day, the 12th, they had deployed in three parts, one to guard the rear, one to seal off the eastern escape route from Harper's Ferry, and one to seize Maryland Heights.

Jackson's rapid advance down the Virginia side of the Potomac had forced the 2,500 Federals in Martinsburg to fall back to Harper's Ferry on 11 September. That put the Union strength in the town at over 14,000 men. Unfortunately, once the rebels got there, they would outnumber the Yankees by 7,000 men -- and besides being potentially outnumbered and holed up in a wretched defensive position, many of the soldiers were inexperienced, and their leadership in particular left much to be desired. Their commander was Colonel Dixon S. Miles, an old regular who had a good record from the Mexican War and Indian fighting, but had suffered troubles with the bottle and seemed to be showing his age. A fellow officer said that he "needed near him a man with sound judgement in order that misdirection and eccentricity might be prevented."

There was no such man near him. The first and most serious misjudgement Miles made was to not pull out of Harper's Ferry immediately. A retreat in the face of an advancing enemy was risky in the extreme, but remaining where he was amounted to suicide. This error was compounded by his deployment of his soldiers. He put most of his men on Bolivar Heights, left only 2,000 on Maryland Heights, the highest and most strategically important of the surrounding ridges, and left Loudoun Heights almost completely undefended.

The Confederates advanced up narrow and steep paths onto Maryland Heights on 12 September. Late that evening they ran into the Union defenders, who had set up an abatis, a lacework of felled trees with their branches pointed outward. The Federals fired on the rebels, who decided to wait until morning to advance further.

After the sun came up on 13 September, the Confederates quickly overran the abatis, sending the Federals back to another abatis about 400 yards (360 meters) uphill, in front of a crude breastworks of logs and rocks, protecting the 1,700 Yankees at the top of the heights. The two sides were roughly equal numerically, but the Union soldiers were almost all green. Despite that, under the command of Colonel Eliakim Sherrill, a former US congressman, they threw back two rebel charges.

Colonel Sherrill had little military experience but a good deal of courage, and he energetically encouraged his men to fight back, walking among them and waving his pistol. Then the Confederates charged again. Sherrill recklessly stood up on the breastworks to get a better view and show his defiance, and got a bullet through his cheek for his troubles; he was carried off the battlefield, and his men panicked. Under Confederate pressure, their resistance crumbled. By late afternoon, all the Federals had withdrawn across the Potomac, and Maryland Heights was in rebel hands.

John Walker had arrived at Loudoun Heights that morning at about 10:00 AM with his division of 3,400 men, finding much to their surprise that there were no Yankees there at all. Stonewall Jackson had arrived before Bolivar Heights at about 11:00 AM. By that evening it was apparent to all the defenders that their position was hopeless, all except Colonel Miles, who said: "I am ordered to hold this place and God damn my soul if I don't."

Miles did have the presence of mind to send out a small detachment of cavalry during the night, to contact McClellan and inform him that Harper's Ferry could not be defended for more than 48 hours. If no help arrived in that time, Miles would be forced to surrender.

BACK_TO_TOP