* The failure of Major General George McLellan's slow 1862 drive against Richmond left the Union war machine in the East in some state of confusion, while the leadership shuffled generals and forces around, and President Lincoln considered the emancipation of slaves. Confederate General Robert E. Lee suffered from no such confusion, quickly organizing his Army of Northern Virginia for a drive north -- leading to a clash at Centerville, Virginia, followed by a second battle of Bull Run.

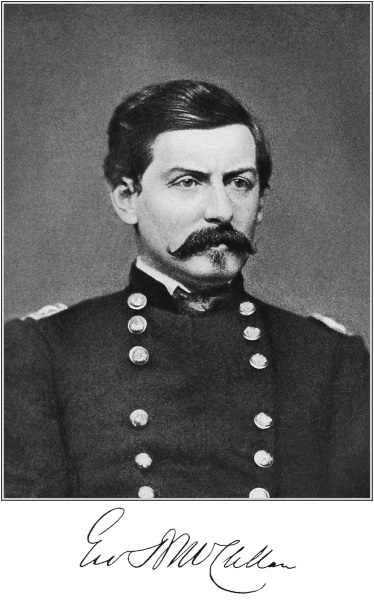

* During the spring of 1862, it seemed as if the days of the Confederacy were numbered. The South had suffered a string of defeats, while a Union offensive, plodding forward under the command of Major General George Brinton McClellan up Virginia's James River Peninsula, seemed certain to seize Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy.

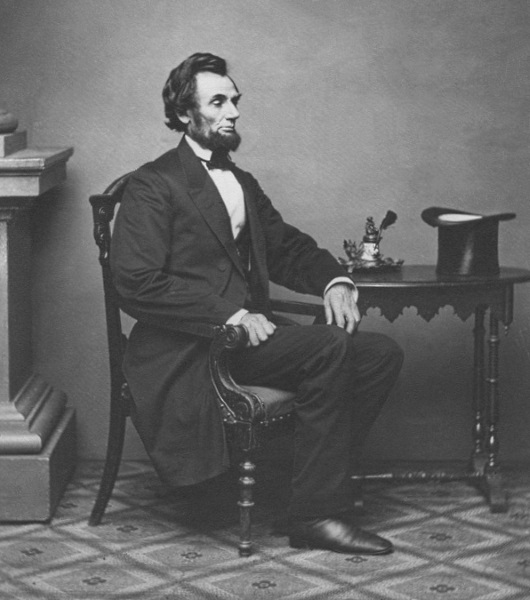

However, after the commander of the opposing Confederate forces, General Joe Johnston, was wounded in action, he was replaced by General Robert E. Lee -- who promptly took the offensive, leading to the chaotic "Seven Days' Battles", intimidating McClellan into abandoning his advance. By 1 July 1862, McClellan's Army of the Potomac had withdrawn to a defensive position at Harrison's Landing on the James River. His forces were demoralized, many of the troops knowing they could have defeated the rebels had their leadership been less timid. The confidence of Union President Abraham Lincoln in McClellan, which had been steadily declining, was all but exhausted.

Lincoln decided to visit McClellan's forces at Harrison's Landing, arriving by steamer on the afternoon of 8 July. On riding with McClellan to inspect the troops, the President was encouraged to find that the men, who had been generously resupplied, seemed in good spirits and good condition. An Army chaplain found the sight of the lanky President trying to ride a nervous horse too small for him comical, but had to add: "The boys liked him, his popularity is universal ... all have faith in Lincoln. 'When he finds out,' they say, 'it will be stopped.' ... God bless this man and give answer to the prayers for guidance I am sure he offers."

McClellan, who had always regarded Lincoln as a crude hick, did not feel any such admiration, writing his wife later that Lincoln was "an old stick and of pretty poor timber at that", and said that he had to "order the men to cheer and they did it very feebly."

The President spent the next day conferring with McClellan and his generals, and at this point McClellan made a major error of judgement. A few weeks earlier, the general had asked the President for permission to present his views on the overall military situation. The President had graciously agreed and suggested they should be submitted in a letter if that would not take up too much time. McClellan now presented Lincoln with the letter. It proposed a war of restraint: "It should not be at all a war upon population ... neither confiscation of property, political executions of persons, territorial organizations of States, or forcible abolition of slavery should be contemplated for a moment." By combining forces under a general-in-chief, the Union would be able to defeat the South's armies in the field and restore the Union. McClellan humbly said he did not seek that post, but would not refuse it.

"All right," Lincoln said, after reading the letter, and stuck it in his pocket without another word. After further conversations with the generals, Lincoln departed later that day and, having given few positive signs, left McClellan fearing the worst -- the general writing his wife with bitter complaints against the President, and more so against Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. McClellan's low estimation of Stanton was perfectly correct, since the war secretary was an intriguer, inclined to double-dealing: writing McClellan continuously to express his unfailing loyalty and devotion, simultaneously working to turn the rest of the presidential cabinet against the general.

While the letter McClellan had presented to the President was a non-starter, the general had no idea of how far off base he really was. The letter had proposed policies for a restrained war, at the very time Lincoln was realizing that a restrained war was out of the question. For example, in response to protests against the authoritarian measures his armies had imposed in conquered regions of the South, Lincoln had recently written a reply:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

What would you do in my position? Would you drop the war where it is? Or would you prosecute it in future with elder-stalk squirts charged with rosewater? Would you deal lighter blows rather than heavier ones? Would you give up the contest, leaving any available means unapplied?

END_QUOTE

He added in a letter: "I shall not surrender this game leaving any available card unplayed." If that meant confiscations, arbitrary arrests, reducing Confederate states to subjugated provinces, or, most of all, emancipation of the slaves by force -- then so be it. McClellan had clearly proven with his letter that he wasn't the kind of general who could fight such a war.

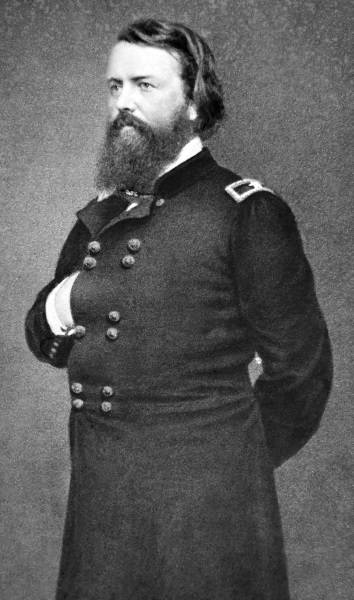

Lincoln made up his mind. On the morning of 11 July, Major General Henry W. Halleck, in charge of Union forces in the Western theater, received the following telegram:

ORDERED. THAT MAJ. GEN. HENRY W. HALLECK BE ASSIGNED TO COMMAND THE WHOLE LAND FORCES OF THE UNITED STATES AS GENERAL-IN-CHIEF, AND THAT HE REPAIR TO THIS CAPITAL AS SOON AS HE CAN WITH SAFETY TO THE POSITIONS AND OPERATIONS WITHIN THE DEPARTMENT UNDER HIS CHARGE.

* The growing disgust with McClellan's lack of aggressiveness had led the Lincoln Administration to order Major General John Pope to come to Washington DC, and take command of Union forces in northern Virginia. Pope had made a name for himself with victories against Confederate forces in the upper Mississippi; although he was well-known as a loud-mouthed braggart, nobody doubted his aggressiveness, and the belief was that his willingness to fight, a quality notably lacking in McClellan, would outweigh his defects.

Pope had arrived in late June, delighting hard-war Republicans in Congress with his tough talk. Since that time, he had been trying to weld his forces -- now organizationally assembled as the "Army of Virginia" -- into an effective striking force. It was not an easy job, and Pope was not doing it well. The separate commands he had inherited were burdened with traditions of defeat, burdened with traditions of defeat and a lack of confidence in their corps commanders:

Pope's major concern was the morale of his troops. In an attempt to deal with that problem, Pope began his command of the Army of Virginia by issuing a ringing address titled "To the Officers and Soldiers of the Army of Virginia", and which ran in part:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

Let us understand each other. I have come to you from the West, where we have always seen the backs of our enemies, from an army whose business it has been to seek the adversary and to beat him when he was found; whose policy has been attack and not defense ... I presume that I have been called here to pursue the same system and to lead you against the enemy. It is my purpose to do so, and that speedily.

END_QUOTE

The speech was a disaster. One of his brigadiers called it "windy and insolent", and the men began to call their new leader the "Five-Cent Pope". Pope wasn't making any friends elsewhere in the US Army, either, his loud criticisms of McClellan having offended many in the Army of the Potomac. In short, Pope was getting off to a bad start. When he issued messages signed "Headquarters in the Saddle", jokes began to circulate that suggested Pope had a certain confusion between his headquarters and his hindquarters. His violent talk of harsh measures against Confederate civilians made him one of the most hated Yankees in the South.

* Pope did move quickly. On 12 July, he ordered Nathaniel Banks and his corps to Culpeper Court House, a rail stop to the west of the town of Fredericksburg, Virginia. This move threatened the important rail junction at Gordonsville, 27 miles (43 kilometers) to the south. Banks then ordered his cavalry under Brigadier General John P. Hatch to destroy railroad tracks in the area.

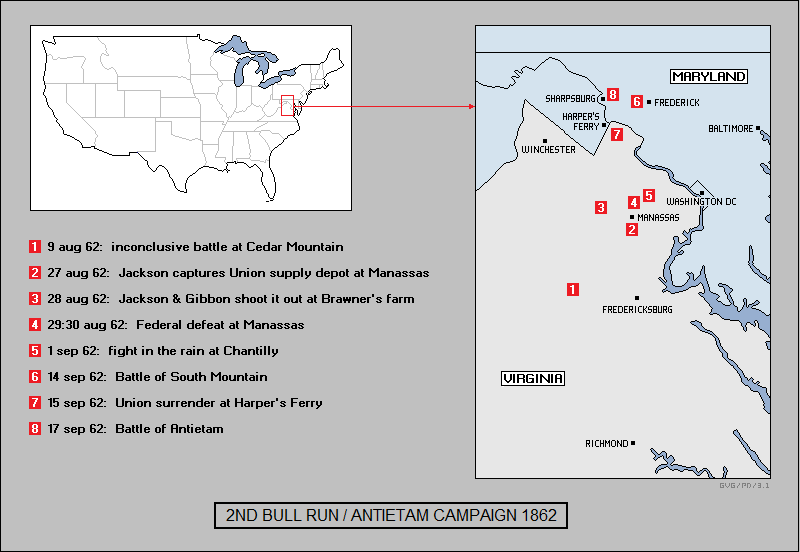

Robert E. Lee learned of the move the day it took place. The next morning, 13 July, he considered the risks of pulling troops out of the defense of Richmond; judged McClellan entirely passive, and not likely to do anything for the moment; then ordered Major General Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson to Gordonsville with two divisions, Jackson's own and Major General Dick Ewell's. A frantic search for railway cars followed. On 16 July, Jackson's 18,000 men piled on to 18 trains, and by the 19th, they were in place around Gordonsville.

Federal cavalry had moved very slowly; Hatch had taken a few days to organize and obtain supplies, and by the time he was ready to move, he found himself blocked by a "Stonewall", with a large number of Confederate troops looking forward to a fight. The raid was called off and Hatch was sacked, to be replaced by a tough, competent Indian fighter, Brigadier General John Buford. Hatch's muddled performance and the continued idleness of McClellan gave Lee further encouragement to take the offensive against Pope.

While Jackson's force was too small to take on the Federals on its own, on 27 July Lee ordered Major General Ambrose Powell "A.P." Hill to take his "Light Division" -- so-called because of its mobility -- and join Jackson. Unfortunately, there was a mismatch in temperaments between Jackson and Hill:

The same message memorably ordered: "I want Pope to be suppressed." Jackson almost certainly saw that in big bold letters, and events built up steam towards a violent collision.

BACK_TO_TOP* The reversals of fortune in a war that had seemed almost won by the Union had, as noted, pushed Lincoln not towards defeatism but to the conclusion that more severe measures were necessary. That meant, above all, emancipation.

The US Congress was already taking some action. Congress had passed a "Confiscation Act" in August 1861, which had established the right of the Federal government to confiscate property of rebels -- notably slaves, who had already picked up the inclination to flee to Yankee lines and declare themselves "contraband of war". It had been a half-hearted measure, in particular not clarifying if such "contrabands" were to be freed.

As a consequence, Congress came up with a "Second Confiscation Act", which President Lincoln signed into law on 17 July 1862. The new Confiscation Act was much less hesitant than the first, authorizing the seizure of all assets of rebel officials and officers, not just their slaves. Rebels would be disenfranchised; slaves that fell into Federal authority whose masters were in rebellion against the United States would be automatically freed; and the President should make provisions for the voluntary relocation of them in "some tropical country beyond the limits of the United States."

To cap it all, the act specified that "the President of the United States is authorized to employ as many persons of African descent as he may deem necessary and proper for the suppression of this rebellion, and for this purpose he may organize and use them in such manner as he may judge best for the public welfare." In other words, it authorized a measure that was one of the worst nightmares of Southerners: the arming of their slaves to fight the Confederacy.

Despite the strong language, there was still less there than met the eye. Enforcement was not defined, and even President Lincoln felt that Congress was exceeding its authority in freeing a slave. He agreed to the law under the clarification that the slaves in question were war captives and legally Federal property. Nothing was said about the slaves in the border states, and the legality of slavery remained formally intact. The law was still a major political blow to the teetering structure of slavery. Property rights that were revocable on the basis of the owner's political sympathies were weak, and using freed slaves to suppress the rebellion was implicitly setting slavery against itself. No one in power who gave their legal assent to such a law could believe that there could be any return to the status quo before the war.

Lincoln certainly did not. On 12 July, he had talked to border state congressmen at the White House to promote the idea of buying up slaves and freeing them. He'd been floating the idea for some time, pointing out that it would be cheaper to buy the slaves and free them than continue the war. He told the congressmen:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

If the war continue long, as it must, if the object be not sooner attained, the institution in your states will be extinguished by mere friction and abrasion -- by the mere incidents of war. It will be gone, and you will have nothing valuable in lieu of it.

END_QUOTE

He tried to reassure them that no drastic measures were intended: "I do not speak of emancipation at once, but of a decision at once to emancipate gradually." Nobody had paid much attention to the President's notions of "compensation emancipation" before, and they didn't then; of the 28 border state men, only eight went along, while the others raised objection after objection. In doing so, they failed to realize that instead of stopping the game, they were simply dealing themselves out of it. The logic of war almost forced the Union to take action against slavery, and the attempts by pro-slavery congressmen to simply brush off the issue handed the cards to their antislavery colleagues, who generally found Lincoln's talk of gradual and compensated emancipation weak and contemptible.

On 13 July, Lincoln attended a funeral. The Stantons had lost a newborn, and the President went to the ceremony in a carriage with Navy Secretary Gideon Welles and Secretary of State William Seward. The President clearly had something on his mind, and spoke earnestly on the propriety of emancipation as a "military necessity absolutely essential for the salvation of the Union, that we must free the slaves or be ourselves subdued." The two cabinet secretaries were somewhat startled by this unexpected change in thinking, and gave cautious answers -- but clearly something had hold of Lincoln's mind and wasn't about to let go.

On 22 July, the President assembled his cabinet and read to them an emancipation proclamation, to be implemented immediately. Welles and Seward had expected something along such lines; it was now the turn of the other cabinet secretaries to be shocked. They sorted out their opinions. War Secretary Stanton and Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase wanted something stronger; Attorney General Edward Bates liked it as it was; Navy Secretary Welles wanted something weaker; Postmaster General Montgomery Blair and Interior Secretary Caleb Smith didn't want it at all, at least not before the elections in the fall.

Finally, Secretary of State Seward spoke, approving of the proclamation, but questioning that the time was right for it. He reasoned that in the face of the defeats the Union cause had so recently suffered, "it will be considered our last shriek on the retreat." Seward recommended that it be postponed until the North had won a battlefield victory. Nobody in the cabinet was closer to Lincoln than Seward; the President had not thought of that, considered it, then agreed. He put the proclamation aside, to be retrieved when a military victory unlocked the door for it.

* It took Major General Henry Halleck about two weeks to tie up loose ends in his far-flung Western department; he did not arrive in Washington until 23 July 1862. Once there, he immediately left for Harrison's Landing on the James to confer with General McClellan. McClellan had not been informed of the change in command when the decision had been made, and only learned about it in a newspaper article on 20 July. He was offended, and with very good cause, writing his wife: "In all these things, the President and those around him have acted so as to make the matter as offensive as possible. He has not shown the slightest gentlemanly or friendly feeling, and I cannot regard him in any respect as my friend."

McClellan was discouraged and restless. He had recently entertained in his camp Fernando Wood, just elected mayor of New York City, and a conniving Southern sympathizer. The two men had talked politics; Wood suggested that McClellan consider the presidency, and in response McClellan wrote a letter outlining his political views. However, McClellan had the sense to run the letter past one of his officers, Major General William F. "Baldy" Smith. Smith took one look at it, then replied in shock that "it looks like treason", and it would lead to disaster if it was ever published. Certainly handing such a document to a shifty fellow like Wood was tempting political suicide. McClellan destroyed the letter, but his enemies in Washington were perfectly aware that Wood had paid him a visit, and could imagine its significance.

In any case, when Halleck arrived, he wasn't enthusiastically received. McClellan had a low opinion of his new superior, as did most people who had to deal with Halleck. McClellan later remarked: "I do not think he ever had a correct military idea from beginning to end."

McClellan still managed to keep from stepping on Halleck's toes. Indeed, McClellan was full of grand offensive plans for another drive on Richmond, but since Robert E. Lee so monstrously outnumbered him -- McClellan believing Lee had 200,000 troops -- massive reinforcements were needed. Halleck responded that no more than 20,000 men were available, and if that wasn't enough to do the job, the Army of the Potomac would have to be withdrawn from the Peninsula. If they couldn't do anything, what was the point of keeping them there? Somewhat startled by this obvious logic -- Halleck clearly did have at least a few correct military ideas in his head -- McClellan excused himself to confer with his corps commanders, and in the morning said he felt he could give it a try with that number of men.

Halleck returned to Washington, only to find a telegram waiting for him. The message had apparently been sent immediately after his departure, and related how enemy reinforcements were "pouring into Richmond". Another 20,000 men would be required. Halleck was flabbergasted and went to the President, who hardly blinked. He told Halleck that if the Army of the Potomac was given 100,000 men, McClellan would be delighted and promise to be in Richmond the next day. The next day would come, McClellan would report that the enemy had 400,000 men, and ask for 100,000 more reinforcements.

Halleck considered that, to come to another logical conclusion that McClellan hadn't thought of. If the grand reports of rebel strength that McClellan was continuously citing were true, then leaving Pope's and McClellan's armies separate was inviting destruction in detail; better to combine them immediately. On 29 July, Halleck ordered every steamer in Baltimore to proceed to the James, and on 30 July he ordered McClellan to evacuate his sick and wounded "in order to enable you to move in any direction." McClellan was very suspicious, and again with good cause: Halleck had already made up his mind to withdraw the Army of the Potomac from the James.

After a month's sullen idleness, McClellan's army was going into motion again. In what direction was very uncertain, all the more so because of the impression the man in charge, Henry Halleck, made on those around him.

There was nothing very impressive in Halleck's appearance. He was flabby, slouchy, rumpled, goggle-eyed, almost always grumpy, and lacking in energy. He had an unnerving tendency to address people while staring at some point in space over their shoulder, and a mannerism of slowly rubbing his elbows while lost in thought, a habit that exasperated Navy Secretary Welles. Welles had occasions to work with Halleck, but always went away wondering what had been accomplished. Welles wrote that Halleck had "a scholarly intellect and, I suppose, some military acquirements, but his mind is heavy and irresolute." Into the hands of this man had been entrusted the direction of the entire US Army.

BACK_TO_TOP* Although the Union Army of the Potomac was idle along the James at Harrison's Landing, it was still a powerful force, and if somebody with drive were to put it into motion, there was not much Robert E. Lee could have done to stop it. There was actually little fight in George McClellan -- but for all Lee knew, McClellan was getting ready to renew his attack on Richmond, while John Pope drove down from the north.

Lee needn't have worried about McClellan. That same Sunday, the order came from Halleck to withdraw the Army of the Potomac to the Aquia Creek base, on the Potomac near Fredericksburg. After four months of intermittent fighting, McClellan's Peninsula Campaign was over. It had started out in confidence that the Union would certainly capture Richmond, but had ended up a dismal failure; worse, it was almost entirely a failure of leadership, of a general with less nerve than that of the men that he led.

Even though Lee was uncertain of McClellan's intentions, Lee could easily envision the Army of the Potomac being transferred to northern Virginia. That prospect gave Lee both an opportunity to strike, and an immediate need to do so. Once it was deployed in northern Virginia, the combined force would represent a grave threat to Lee. It was best to deal with Pope while the opportunity lasted. Once Pope was dealt with, Lee would then be freed for offensive actions against the North. Lee gave Stonewall Jackson general orders to take on Federal forces in Northern Virginia. Jackson's forces moved out of their camps around Gordonsville, Virginia, on Thursday, 7 August.

McClellan, at that time, was little more than a bystander to events, with not much more to do than manage the transfer of his command. Pope, on his part, was starting to demonstrate that he was in over his head. On Friday, 8 August, Pope transferred his headquarters to Culpeper Court House and ordered Banks to take his two divisions south to counter Jackson's movement. Banks was eager to fight, though he knew that aware that he had only 8,000 men to the 30,000 reported for Jackson.

The opposing forces made contact the next day -- Saturday, 9 August -- near a landmark named Cedar Mountain. Banks then got an order from Pope to attack the enemy "as soon as he approaches", with reinforcements to be sent to back him up. Banks, though no military professional, was shocked at the idea of throwing himself at such a larger force, with only vague reassurances of reinforcements to back him. Nonetheless, he swallowed hard and did so.

The battle started at noon, picking up fury in the late afternoon, with the fighting not dying out until darkness made it impossible to do so. The result was a mindless brawl, with the Union men fighting fiercely and pressing the rebels hard at first; but ultimately, simple numbers won out, with the Federals getting much the worst of it, the Battle of Cedar Mountain being a clear Union defeat. The Confederates lost over 1,300 men, the Federals over 2,400, many of them taken prisoner. It had been a soldier's battle; the Federals in particular had shown extreme courage in the face of a superior force.

There was no credit in the action to their generals. Banks' command to attack was rash, with Pope bearing as much or more responsibility for his vague and irresponsible orders. Jackson had demonstrated little in the way of military judgement, and had the odds been more even, the Confederates would have very likely been defeated. Jackson privately told one of his staff that the Battle of Cedar Mountain was "the most successful of his exploits." The critics carped at him; some called him arrogant; mad; no better than lucky, at best.

Pope had brought up reinforcements, expecting another battle -- but Jackson, recognizing the odds were no longer in his favor, pulled out south on Monday night, 11 August. Jackson wasn't really retreating, that wasn't an idea he understood very well; he was simply regrouping to renew the fight on more even terms. By this time, Lee was getting solid intelligence of the shift of McClellan's forces to Pope's command.

* On 13 August, the day after Jackson returned to Gordonsville, Lee sent Major General James Longstreet with ten brigades to reinforce Jackson for more ambitious offensive operations. Longstreet was a level-headed, low-key, strong-willed man who rubbed along well enough with Jackson, partly by not taking Jackson any more seriously than he saw good cause to do.

Lee arrived in Gordonsville on 15 August to find that Pope had obligingly placed all his forces in a trap. Pope's men occupied a triangle bounded by the Rappahannock on the north, the Rapidan on the south, and the O&A railroad on the west. The Rappahannock and the Rapidan joined about ten miles (sixteen kilometers) west of Fredericksburg. If Pope's forces could be driven east into the junction of the two rivers, they could be penned in and destroyed with little chance of escape.

It was a neat plan -- but it quickly unraveled in confusions. The commander of Lee's cavalry division, Major General James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart -- a daring, flashy cavalryman, who wore a cape and a plumed hat -- was to take his command out late on Sunday, 16 August, and burn the vital railroad bridge over the Rappahannock. The rest of Lee's forces would move out once the sun came up on Monday morning. Due to miscommunications, the two brigades in Stuart's command failed to coordinate their actions; worse, Stuart and his staff ran into Yankee cavalry during the night. Most of the rebels got away, but the Federals did capture a Confederate captain who had orders outlining Lee's plans in his dispatch case. Much to Stuart's fury, the Union cavalry also made off with his cape and plumed hat.

Things having gone awry, Lee rescheduled the attack for 20 August -- but Pope, having inspected the orders in the captured dispatch case, started to pull out in haste on 18 August. By the 20th, when Lee departed, Pope's forces were mostly north of the Rappahannock. If Pope was contemptuous of the defensive in theory, he was demonstrating great skill at it in practice.

BACK_TO_TOP* Lee now faced a theater of action that could be contained in a rectangle. The base of the rectangle was the Rappahannock River on the southeast, with the O&A railroad on the southwest, the Bull Run stream on the northeast, and a string of low mountains, the Bull Run mountains, on the northwest. The rectangle was about 25 miles (40 kilometers) west of Fredericksburg and the Aquia Creek base, where Union reinforcements were arriving.

The O&A ran over three streams, with Cedar Run in the south, Broad Run towards the north, and Bull Run at the very top of the rectangle. There was a whistle stop named Catlett's Station near Cedar Run, another named Bristoe Station at Broad Run, while Pope's big supply base at Manassas was between the Broad Run and the Bull Run.

The Warrenton Pike ran through the middle of the rectangle parallel to the O&A, passing through Warrenton in the south, then north through Gainesville, Groveton, over the hilly country where the battle of Bull Run had taken place the year before, and then out of the rectangle towards Alexandria and Washington.

The Bull Run mountains on the northwest were cut by a pass named Thoroughfare Gap, through which the Manassas Gap railroad line ran from the town of Salem on the west of the mountains to the towns of Hay Market and Gainesville, and finally to the Union supply base at Manassas. All in all, the area provided a region of varied terrain that provided considerable inspiration to a general with Lee's disciplined imagination. The most noticeable detail was that the O&A could be cut at three bridges within that region. Since Pope was dependent on that railroad, destroying any one of those bridges would greatly inconvenience him.

By 24 August, the Yankees were in front of Lee in such strength that he had no hope of dislodging them by a direct attack. However, Pope was still dependent on the O&A railroad lifeline, and by convincing Pope that his lifeline was in serious danger, Lee might be able to force Pope to retreat, throwing confusion into the imminent link-up of Federal forces and leaving the Yankees disorganized, scattered, and vulnerable to attack in detail.

Lee decided to divide his forces, sending Stonewall Jackson with three divisions to move on the Federal supply base at Manassas, while Longstreet held the line on the Rappahannock with four divisions. Jackson was to move out in the morning, advance behind the screen of the Bull Run Mountains, descend around the mountains through Thoroughfare Gap, and raise hell in Pope's rear along the O&A. It didn't matter where, just as long as it properly scared Pope, and, God willing, nervous Yankee politicians in Washington. Lee and Longstreet were to follow along the same route after a day or two. If Jackson managed to stampede Pope, the two wings of Lee's army would then reunite near the old Bull Run battleground to exploit any blunders Pope might make.

* McClellan arrived over the Potomac by steamship that day, 24 August, trailing the soldiers he had been sending north to John Pope over the last two weeks. They had not been pleasant weeks for him. He had no reason to like Pope, and experience had taught him not to believe a word he was told by his superiors. Halleck had sent him reassurances, saying that: "It is my intention that you shall command all the troops in Virginia as soon as we can get them together." -- and sent McClellan's friend, Major General Ambrose Burnside, to provide encouragement. Burnside was an uncomplicated, honest, outgoing, likeable fellow, completely lacking in guile; nobody would mistrust him, but McClellan was beyond simple reassurances.

Halleck had been shrill and continuous in his badgering of McClellan, to the point where McClellan had felt obligated to complain about the "tone" of the messages he was receiving. When on 21 August he had received a message saying that Pope's forces were hard-pressed he felt an unavoidable satisfaction, writing his wife: "Now they are in trouble they seem to want the 'Quaker', the 'procrastinator', the 'coward', and the 'traitor'. Bien." As he left on the 23rd, he had further written his wife: "I take it for granted that my orders will be as disagreeable as it is possible to make them -- unless Pope is beaten, in which case they will want me to save Washington again. Nothing but their fears will induce them to give me any command of importance or treat me with otherwise than with discourtesy."

McClellan was completely correct. When he arrived at Aquia Creek, he wired Halleck for instructions, and was told in reply that he could stay at Aquia Creek or Alexandria, "so as to direct the landing of your troops". It didn't matter where McClellan went; his only role was to simply help in the handing over of his divisions to Pope. He was, for the moment, no more than a bystander to events.

Those events were beginning to reveal a pattern of confusion among the Federals. While Pope was accumulating an enormous army, as noted it had been originally thrown together from separate commands. Adding new elements from the Army of the Potomac, which had a collective distaste for Pope that he had done much to encourage, hardly made it more coherent.

Whatever confusion took place among the Federals, Lee was certain to exploit. A little over a week earlier, McClellan had written Halleck, saying: "I don't like Jackson's movements. He will suddenly appear where least expected." McClellan had his moments of perceptiveness: in fact, Stonewall Jackson was busily preparing exactly such a magic trick.

* Stonewall Jackson's men moved out at sunrise on Monday, 25 August 1862, beginning their move into Pope's rear behind the shield of the Bull Run Mountains. Federal lookouts reported the departure to Pope, but he failed to understand what was going on.

Jackson pushed his men hard, through the day, well into the next after a short night's sleep. To get into the rear of Pope's forces, they had to pass through Thoroughfare Gap, which was a narrow cut with steep, rocky sides. If the Federals were holding it, they would be very hard to dislodge; but Jackson had moved both swiftly and silently, and the pass was unguarded.

The rebel's initial target was Bristoe Station on the Broad Run. Burning the railroad bridge there would cut the O&A; Pope would neither be able to receive supplies and reinforcements, nor easily send men up the rail line to chase after Jackson. In late afternoon, the Confederates descended on Bristoe Station, achieving complete surprise -- derailing two trains and burning the bridge, though one train managed to reverse and go back north to spread alarm.

With Pope distracted, that afternoon Lee had dispatched Longstreet to follow Jackson's path behind the Bull Run Mountains. Longstreet moved out with five divisions, 32,000 men, a single division being left behind to protect the Rappahannock crossings. Among his division commanders, the most noteworthy was Brigadier General John Bell Hood -- an adoptive Texan, noted for extreme aggressiveness, if not any strong inclination to carefully think things out. His division included his brigade of Texans, who were to a man enthusiastic fighters as well.

That night, Jackson's men moved on Pope's supply base at Manassas, not far from Bristoe Station, enjoying a huge party on the Federal stores there. The sutlers' wagons were full of particular prizes, from canned lobster to Rhine wines. One of the privates would recall decades later: "It makes an old soldier's mouth water now just to think of it." They took what they could carry, and burned the rest.

BACK_TO_TOP* By that time, the authorities in Washington were becoming aware that something was very wrong, bewildering reports coming in by telegraph suggesting the Confederates were everywhere and anywhere. Pope, however, was almost ecstatic, believing he had an opportunity to destroy Jackson. Pope wired orders to his corps commanders to get their forces on the move, telling McDowell:

IF YOU MARCH PROMPTLY AT THE BREAK OF DAWN UPON MANASSAS JUNCTION, WE SHALL BAG THE WHOLE CROWD.

Pope had the right idea, but his lieutenants had good reason to wonder if it was really that simple. Pope, on hearing reports of continued fireworks at Manassas Junction, believed that Jackson was still there, conveniently waiting to be "bagged". Pope had no idea at all of the disposition of the rest of Lee's forces, who might well be assumed to be on the move themselves. McDowell was cautious enough to send a division to guard Thoroughfare Gap.

However, when Pope's forces finally got to Manassas Junction at noon on Thursday, 28 August, they found no rebels there. All that was left were ashes, ruins, and the scattered cast-offs of "the recent rebel carnival". Nobody had the least idea of where Jackson and his men had gone, with the result that the elements of Pope's command ended up in confused marching and counter-marching that frustrated them and wore them down.

Jackson had actually, after some confused marching of his own, managed to get his men reassembled at Stony Ridge, north of the Bull Run battlefield, by that afternoon of 28 August. A map drawn that day of the immediate area would have showed the Manassas Gap railroad, running towards Thoroughfare Gap at the bottom. At Gainesville, the Warrenton Turnpike crossed the railroad, running northwest through Groveton and then over the Bull Run on a "Stone Bridge". It was roughly ten miles (16 kilometers) from Gainesville to Centerville.

Jackson was still feeling aggressive, and just before sundown, he observed a column of Union soldiers, heading for the Stone Bridge, and went down to scout them out personally. The Federal column was the 4th Brigade of Major General Rufus King's division, under the command of Brigadier General John Gibbon. Gibbon was a 35-year-old regular with a background in artillery, a West Pointer -- and a Southerner, a North Carolinan. He had gone with the Union, while his three brothers had signed up for the Confederacy.

Gibbon's four volunteer regiments, about 2,100 men, were all from the West and were almost entirely green. They were called "strawfoots", from the custom of drilling the more ignorant recruits by tying straw to one boot and hay to the other so they could tell one foot from another. The 2nd Wisconsin had seen a little action, but the 6th and 7th Wisconsin and the 19th Indiana had never fired a shot in anger.

Gibbon had an instinct for leadership, however, and the men were well drilled. Gibbon had a reputation for being "steel cold", and by his own admission believed that a good commander was a "despot", but his despotism was moderated by the fact that his men had, after all, volunteered and wanted to be good soldiers. He found that to such men carrots meant more than sticks, and to instill esprit he had issued them regular-army broad-brimmed black hats. They called themselves the "Black Hat Brigade".

Gibbon's men had paid Jackson no mind, thinking him no more than a solitary rebel cavalry scout, but when Jackson's officers saw their commander return, they felt a combination of excitement and dread. One of them said: "Here he comes, by God." Jackson rode up to them, halted, touched his cap, and said calmly, his frustration resolved: "Bring up your men, gentlemen."

The Confederates threw themselves at Black Hat Brigade on a stretch of turnpike just below a farm owned by a fellow named Brawner, with about 6,200 rebels to 2,100 Yankees, and hit them with a devastating volley. If Jackson had hoped to panic the Yankees by surprise and superior numbers -- which he would have believed all the more if he had known how green Gibbon's men were -- he was thoroughly mistaken. The rookies returned the fire and, instead of falling back, advanced. The rebels had simply made them angry.

The two sides slammed away at each other, for the most part the men standing upright, with no cover, just firing and loading and firing again at close range. Gibbon's men received reinforcements and went on with the fight. The firing was terrific, and many soldiers would later call it the loudest they ever heard. It only stopped when it was too dark to shoot any more. Nobody had given any ground; they had just stood there and shot each other. About a third of the 2,800 Federals involved in the battle had fallen; they had bloodied Jackson's men even worse -- one of the casualties being Dick Ewell, who had to have a leg amputated.

From any practical viewpoint, the Battle of Brawner's Farm had been senseless, resulting in no more than mutual bloodletting to no great advantage of either side. In a moral sense, however, it was a victory for the Federals. Rebels who were used to walking roughshod over Yankees had attacked a force no more than half their size under the impression they would throw the Union men off the battlefield -- and smashed into a brick wall that didn't budge an inch.

From then on, the rebels would call the 4th Brigade "them damned black-hat fellers" whenever they came up to the line, a big compliment from an adversary. The Westerners would call themselves the "Iron Brigade", and few would dispute it. In a matter of hours they had gone from a gang of rookies to one of the toughest units in the US Army, and had paid for that distinction in streams of blood.

Still, from the wider point of view, the confrontation had served Jackson's purpose. If it had shown none of the brilliance that he was capable of, he had wanted to distract Pope, and the nasty fight at Brawner's Farm was certainly enough to get John Pope's attention, as well as distract it from elsewhere.

That same afternoon, Lee and Longstreet had reached Thoroughfare Gap. They had hoped it would be unguarded, but now the Union troops dispatched by McDowell were there in force. Longstreet, a hard man to rattle, was undisturbed. He kept up the pressure at the mouth of the gap while dispatching various units to climb the hills around it and attack the Federals men from the rear. It was a tough fight, but the Union troops finally had to give way and withdraw. What compounded this defeat was the fact that the news of the action didn't reach Pope. Pope had no idea that Lee and Longstreet were moving to Jackson's aid and, in his fixation on destroying Jackson, had all but put them out of his mind.

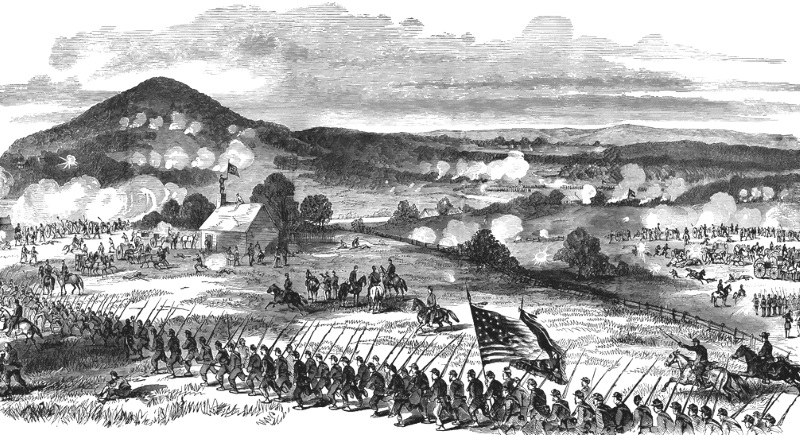

* John Pope was at Centerville the evening of 28 August 1862, in his pursuit of Stonewall Jackson. Pope was delighted to hear of the fighting near Brawner's Farm, since it meant that Jackson had finally been located, and so in principle could be destroyed. However, Pope was having trouble getting his command assembled, and when the assault on Jackson's position began next morning -- Friday, 19 August -- it was performed piecemeal, with whatever forces Pope had at hand.

The Federals still pressed Jackson hard, but he was encouraged by news that Lee and Longstreet had arrived. About 10:30 AM, rebel reinforcements started filing in to extend Jackson's position to the south, siting themselves across the Warrenton Turnpike along the western side of the battlefield. By noon, they were in place.

Pope's clumsy attacks on Jackson's position continued for a day. One of the reasons he was unable to concentrate his forces was that Union troops moving up from the south found their way blocked by a substantial number of Confederates -- Longstreet's men. To the extent the news of the presence of these rebels reached Pope, he ignored it. Clashes continued until it was too dark to fight any more.

Although Washington had been reduced to complete confusion, during that day it seemed like things were looking up, with Pope wiring in that he was "driving the rebels handsomely." McClellan, however, seemed unenthusiastic at the very least. That day, Lincoln jumped into the volley of messages going back and forth between Halleck and McClellan to ask for a situation report. The message he got back from McClellan was startling:

I AM CLEAR THAT ONE OF TWO COURSES SHOULD BE ADOPTED: 1ST, TO CONCENTRATE ALL OUR AVAILABLE FORCES TO OPEN COMMUNICATIONS WITH POPE; 2ND, TO LEAVE POPE TO GET OUT OF HIS SCRAPE, AND AT ONCE USE ALL OUR MEANS TO MAKE THE CAPITAL PERFECTLY SAFE.

Lincoln found McClellan's tactless phrasing both revealing and infuriating. John Hay, one of Lincoln's private secretaries, wrote in his diary that the President was outspoken in his anger, and noted: "He said it really seemed to him that McC wanted Pope defeated."

BACK_TO_TOP* Pope was in fine spirits at dawn on Saturday, 30 August 1862. He believed he had Jackson on the ropes, which was true as far as that went, and sent a message to Halleck describing the enemy as "badly used up". Though Pope conceded his own losses at 10,000, he described the rebel's casualties as "two to one" of his own -- a gross exaggeration, based on no real intelligence available to Pope. His intelligence also failed to consider that Longstreet was on his flank.

Pope took his time to get his forces together, and threw themselves at Jackson in mid-afternoon. Jackson's line finally wavered on the edge of collapse, and he finally did something he had never done before: he called up the chain of command for help. Lee recommended that Longstreet go to Jackson's aid with a division. Longstreet, always calm, replied: "Certainly, but before the division can reach him, the attack will be broken by artillery."

Longstreet had prepared for this moment, siting 18 guns of an artillery battalion on a low ridge where they could fire up the Federal ranks advancing on Jackson's position. Longstreet gave them the order to fire, and solid shot rolled up the lines of Union soldiers. Longstreet later wrote: "Almost immediately, the wounded began to drop off [the] ranks; the number seemed to increase with every shot; the masses began to waver. In ten or fifteen minutes it crumbled into disorder and turned towards the rear."

The Federal assault, absolutely unprotected from the bombardment, fell apart. The news of Longstreet's success reached Lee, and he had his signalmen flag a message to Jackson's headquarters:

DO YOU STILL WANT REINFORCEMENTS?

The answer came back just as Longstreet had predicted it would:

NO. THE ENEMY ARE GIVING WAY.

At about 4:00 PM, Lee sent an order to Longstreet to tell him to attack with every man he had and exploit the chaos among the Federals. Longstreet's divisions charged forward, the spearhead being Hood and his division. The result was everything but a rout -- not a rout, Pope was finally able to set up a solid defense to protect the withdrawal of his forces in the dark over the Stone Bridge. The last got across at midnight, with the bridge then being blown.

The Union soldiers trudged from their defeat through the rain up the turnpike to Centerville in a state of deep black depression. They had fought their best, but their leadership had not been worthy of them. Pope was slowly realizing just how badly he had been beaten. After retreating to Centerville, he had been optimistic that he could stand and fight and give the rebels a bloodying, but when the dawn came on Sunday, 31 August, his assurance failed. The news of the disaster had by now finally made it to Washington. The public reaction was one of shock and hysteria. President Lincoln had a simple view of things, telling his secretary John Hay: "Well, John, we are whipped again, I am afraid."

* There was a battle on 1 September, in the vicinity of an estate named Chantilly not far from the battlefield of two days before, with the fighting taking place in a torrential downpour. It was necessarily confused, the only notable result being that Union Major General Phil Kearny -- a fighting legend to Union troops -- and Brigadier General Isaac Stevens -- once governor of Washington Territory, then a congressman from that territory -- were both killed.

That was the end of the Second Battle of Bull Run. One regimental historian later wrote that Pope:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

... had been kicked, cuffed, hustled about, knocked down, run over and trodden upon as rarely happens in the history of war. His communications had been cut; his headquarters pillaged; a corps had marched into his rear and had encamped with ease upon the railroad by which he received his supplies; he had been beaten or foiled in every attempt he made to "bag" those defiant intruders; and in the end he was glad to find a refuge in the entrenchments of Washington, from which he had sallied forth, six weeks before, breathing out threatenings and slaughter.

END_QUOTE

Nothing could cover up the humiliation and anger of Pope's men. The soldiers called out insults to Pope as they marched by him, one shouting: "Go west, young man! Go west!" McDowell got the same treatment, the soldiers jeering: "Traitor!" "Scoundrel!"

Federal casualties were about 14,500, including 4,000 prisoners. Confederate losses were about 9,500. The casualty ratio was not in the rebel's favor. The Yankees could bear such losses much more easily than the Confederates. However, a simple body-count is a poor and contemptible measure of military accomplishment. Lee had driven a much larger force than his own off the field, and reduced it to a state of disorganization and demoralization. The game was now in his court, and he had both the opportunity and, given that the Federals had not really been injured worse than himself, the immediate need to exploit his advantage.

BACK_TO_TOP