* The first person to attempt the scientific study of the mind was the 17th-century French philosopher Rene Descartes. His analysis, in hindsight, left much to be desired, in particular promoting a questionable divide between brain and mind. In the following century, the Scots scholar David Hume would question that division -- but he was unsurprisingly ignored, with "Cartesian dualism" and mysticism continuing to plague the study of the mind to the present day.

* From prehistoric times, humans have puzzled over their own awareness, their ability to see and think about the world, as well as themselves; that they were "mindful", that they had a conscious mind. From that realization, the question followed: what exactly is the mind?

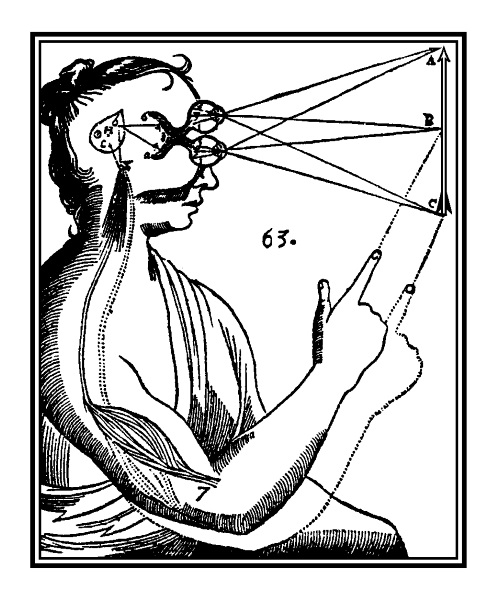

Humans have long had an inclination -- common if not necessarily universal -- to model our mind as manifesting a "spirit" or "soul", an immaterial entity inhabiting a meat body. One of the first to try to nail down that fuzzy idea was French philosopher Rene Descartes (1596:1650), who judged the seat of the soul to be the pineal gland deep in the brain. He reasoned so because the brain is split into left and right halves; the pineal gland bridges the two, suggesting it is of central importance to the brain's traffic.

Descartes was in error. Today, it is known that the pineal gland is an "endocrine gland", which produces the hormone melatonin, important for maintaining the sleep cycle. It's associated with the brain, but serves only a supporting role in the brain's workings. Although the pineal gland does keep resurfacing as an element in fringe science theories, there was no basis for assuming, as Descartes did, that it was the seat of the soul.

Descartes made a more fundamental error in his attempt to nail down the residence of the soul, since in doing so he formalized what is now called "Cartesian duality" or "Cartesian dualism". A cartoonish way of thinking of Cartesian dualism as an "inner self" -- a little person, a "homunculus", in our heads who observes the world outside through the "Cartesian theater" of our eyes, ears, and other senses, or similarly observes memories, or the processes and results of reasonings.

We might call the homunculus "Harvey", after the title of the classic 1950 movie, in which the protagonist, Elwood P. Dowd -- played by Jimmy Stewart -- had an invisible friend named "Harvey". Harvey was supposed to be a giant rabbit, but since he was invisible, his precise form is irrelevant, and any attributes could be granted to him arbitrarily. Invisible beings are like that.

OK, Harvey's silly, but the fact of the matter is that Cartesian dualism, the "ghost in the machine", is silly as well. After all, if we have a conscious mind because we have an inner self, Harvey, then where does Harvey get his conscious mind? If the answer is: "He just does, it just is so!" -- then why bother to invoke an inner self? Why not just claim consciousness "just is so", and dump the excess baggage? Or do we claim the inner self has another inner self at the next level down? Is there yet another inner self below that level as well? And so on, more inner selves forever. We have gained nothing but an infinite regression, a "strange loop", from which Cartesian dualism has never escaped.

In modern times, Descartes is often ridiculed for his notions of the mind -- but the French cognitive researcher Stanislas Dehaene (born 1965) noted that that Descartes was modern in regarding humans as mechanistic, with Descartes stating: "I suppose the body to be nothing but a statue or machine made of earth, which God forms with the explicit intention of making it as much as possible like us."

Descartes compared the human body to a pipe organ, there being no more elaborate device in the 17th century, saying that the functions of the body were equally understandable, including:

QUOTE:

... the digestion of food, the beating of the heart and arteries, the nourishment and growth of the limbs, respiration, waking and sleeping, the reception by the external sense organs of light, sounds, smells, tastes, heat and other such qualities, the imprinting of the ideas of these qualities in the organ of the "common" sense and the imagination, the retention or stamping of these ideas in the memory, the internal movements of the appetites and passions, and finally the external movements of all the limbs.

END_QUOTE

While Dehaene, as a Frenchman, had an obvious motive to be sympathetic to Descartes, one of the giants of French intellect -- the concept of "Cartesian coordinates" is a fundamental element of modern math and physics -- Dehaene also cited the pioneering American psychologist William James (1842:1910) as saying: "To Descartes belongs the credit of having first been bold enough to conceive of a completely self-sufficing nervous mechanism which should be able to perform complicated and apparently intelligent acts."

Why, then, did Descartes invoke the soul to explain the mind? Simply because:

There was nothing new in Descartes' time in thinking humans had a soul; his innovation was to suggest that the idea could be dressed up in scientific clothes. Given that the most complicated machine he could think of was a pipe organ, that incredulity was somewhat understandable. Nonetheless, his "argument of incredulity" yielded nothing but "magical thinking": instead of admitting he knew nothing, he papered over his ignorance with meaningless verbiage, and pretended he had an explanation.

BACK_TO_TOP* Today, transforming the ancient discussion of the mind, we have machines, such as the ubiquitous smartphone, of complexity far beyond what Descartes could have possibly imagined. Even more to the point, machines like smartphones now incorporate "artificial intelligence (AI)" features that can use "words or other signs" to communicate -- which actually is not so hard to do, at least at a basic level -- and perform acts of reasoning.

Nonetheless, the argument of incredulity continues to dog the study of the mind. The idea of "machines who think" continues to provoke outraged protests, despite the fact, as will be demonstrated, that now we do have machines who think. Much of the incredulity is rooted in Cartesian dualism -- which remains alive, if not well, because it has such a strong appeal to intuition.

Cartesian dualism sometimes appears in subtly disguised or indirect forms, one of the prominent ones being the "mind-body problem" -- which, in blunt terms, is the assertion that the mind is not a consequence of the biochemical workings of the brain. This notion was articulated by the German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646:1716):

QUOTE:

One is obliged to admit that perception and what depends upon it is inexplicable on mechanical principles, that is, by figures and motions. In imagining that there is a machine whose construction would enable it to think, to sense, and to have perception, one could conceive it enlarged while retaining the same proportions, so that one could enter into it, just like into a windmill. Supposing this, one should, when visiting within it, find only parts pushing one another, and never anything by which to explain a perception. Thus it is in the simple substance, and not in the composite or in the machine, that one must look for perception.

END_QUOTE

The statement that "one is obliged to admit" is, to put it politely, a reach. Like Descartes, Leibniz was a very intelligent man of great accomplishment, but his reasoning in this matter made no sense. Leibniz simply asserted, without justification, that the mind's ability to perceive had no mechanistic basis, and so it was futile to try to reduce it to the action of components of a system, to see how they enabled the system as a whole. Perception instead had to reside in some basic "substance" underlying and distinct from the physical system -- some kind of a Harvey. Incidentally, this is why Cartesian dualism is sometimes called "substance dualism"; it envisions the mind as having a substance of its own, apart from the biological substance of the brain.

Leibniz might just as well have asserted that keeping time had no mechanistic basis. To understand the operation of a mechanical clock, we break it down into its subsidiary components, determining their individual roles and their relationships. No one component of the clock can keep time by itself. Once we have itemized all the components, identified their functions, and determined their relationships, we have fully understood the operation of the clock, and have nothing more to learn about it. Yes, we might learn more about the fabrication of the components and such, or about other designs of clocks; but such studies would tell us nothing more about the operation of the clock in hand.

Leibniz, in contrast, maintained that since no single component could keep time, the system had to be driven by some underlying principle of "clockiness" inherent in all its components. Leibniz was effectively saying that the mind didn't really have an explanation, that unlike a clock, it couldn't be reduced to the operations of a set of fundamental components. In short, Leibniz embraced:

This issue is another one that continues to bedevil the study of the mind. Incidentally, decomposition and composition are together labeled as "fallacies of distribution".

BACK_TO_TOP* It was the 18th-century Scots scholar David Hume (1711:1776) who was the first to challenge the idea of Harvey, an inner self -- actually, he was the first as far as mainstream philosophy is concerned, the notion having been at least implicit in Buddhism long before, and Hume may have been tipped off by studying Buddhism. In any case -- as Hume put it, in his freshman work A TREATISE OF HUMAN NATURE -- he could not see that the stream of consciousness in the mind was more than:

QUOTE:

... a bundle or collection of different perceptions, which succeed each other with an inconceivable rapidity, and are in a perpetual flux and movement ... The mind is a kind of theatre, where several perceptions successively make their appearance; pass, re-pass, glide away, and mingle in an infinite variety of postures and situations.

END_QUOTE

Our stream of consciousness, as per Hume, is a sequence of dynamic processes that imply awareness -- the acts of seeing, of hearing, of visualizing, of remembering, of reasoning, and so on. When we have no perceptions, when we have no thoughts, then we are not conscious. The stream of consciousness amounts to a shifting and conflicting focus of attention between the processes, with the sense of "self" provided by their melting together through short-term memory into a "bundle" or "gestalt" of the individual components.

When we attempt to examine our thoughts, the very exercise of examination gets in the way, that examination simply taking its place in the stream and displacing whatever perception or idea that preceded it -- to be displaced in its turn by some other perception or idea. There's no mysterious "inner self" watching the stream flow by; the only thing we can do is examine our memories of previous states in the stream of consciousness, which is not the same thing.

Mental processes compete for our attention. We cannot properly concentrate on two things at once, so the processes switch between each other, sometimes rapidly, forming a single stream of consciousness. If we remember one thing, we necessarily forget another, at least for the moment; if we concentrate on something, it displaces whatever it was we had been previously thinking about. How often does our train of thought go off the rails when we're distracted, or simply let the mind wander?

Hume suggested that the "bundle" of mental events in the stream of consciousness ends up being perceived as the self simply because of our instinctive inclination to "simplicity", to think of something in tidy terms because it's less bothersome. This is yet another one of the problems that bedevils the study of the mind: we find it only too easy to read things into it that there's no good reason to believe are there.

However, there's no problem with calling the dynamic collective of our mental landscape a "self". We can also regard the self as a useful visualization, in much the same way that we often visualize ourselves from the viewpoint of our "mind's eye" performing some action, as if we were outside observers -- though few have any problem seeing that as an exercise in imagination. Besides, as discussed later, that visualization is very sketchy.

To the extent we think of ourselves as "I", all the "I" amounts to is an idea, not all that different from our idea of another person, a "you", covering both real and fictional beings. The idea of an "I" isn't even particularly essential; when we become engrossed in an activity, in a Zen fashion we simply do it and, self-consciousness having gone quiet, forget the thought of "I".

Put another way, humans are "perceivers", simply because they perceive, and necessarily perceive themselves perceiving. We are aware that we are aware, the mind providing a mirror of itself. The idea that we are perceivers because we have some "inner self" or "inner perceiver" is passing the buck, talking in circles, saying nothing interesting; the "inner self" is just so much excess baggage, we just perceive and that's it, the buck stops there. We find that idea hard to grasp simply because, there being nothing else like consciousness in our experience, we have nothing to compare it to -- or at least we didn't, before we figured out how to build machines who think.

Once grasped, this "monist" or "pragmatist" view of consciousness -- as opposed to the dualist view of the mind advocated by Descartes -- seems hardly alarming, since it in no way changes our awareness of existence. It's like the old gag about the person who was startled to find out he'd been speaking prose all his life, and hadn't realized it.

The pragmatic point of view honestly is problematic, however, since from Hume's time it has often and unfortunately been expressed as: "Self is an illusion." That is often interpreted as Hume saying he didn't believe he really existed. Nonsense. He had no issue with the idea that humans are aware and are perceivers, that each had a unique set of experiences and memories, that each had a mind; he just did not see that the notion of some "inner perceiver" was justified, or even made any sense.

Indeed, since the "inner self" can be identified with the mind, Hume has been accused of saying that humans have no mind. Nonsense again; if we identify the stream of consciousness, backed up by our store of memories, as the mind, there's absolutely no difficulty. The mind isn't a "thing in itself"; it's no more or less than the elaborate and structured set of behaviors generated by the brain -- feeling, perception, thought, action. This is reflected in common usage of the term "mind":

In modern terminology, the mind is just what the brain does: "the brain in run-time." What else might the mind be? If it's more than the brain in run-time, then what else is it? If nobody can give a useful description of what else, then the conversation is effectively over, or at least can go nowhere forever.

Is there really a "mind-body problem"? It is only a problem if we think of the mind as some sort of immaterial, magical "second brain" -- Harvey -- that we have to think with. We already have a brain, why do we need a second magic brain? As the physicists like to put it: "Who ordered that?"

Hume himself didn't think he was saying anything particularly outrageous once matters were properly understood:

QUOTE:

... all the nice and subtile questions concerning personal identity ... are to be regarded rather as grammatical than as philosophical difficulties ... All the disputes ... are merely verbal, except so far as [such a consideration] gives rise to some fiction or imaginary principle of union [an inner self] ...

END_QUOTE

Despite that, Hume found himself on shaky ground, becoming the target of outraged criticisms. Indeed, by saying the mind was a "kind of theatre", wasn't he implicitly endorsing Cartesian dualism? This would prove another long-standing difficulty in understanding the mind: people seem so naturally inclined towards dualism that it's hard to avoid slipping into it.

Hume was intellectually cautious, fast to give up positions he knew he couldn't defend; he quickly distanced himself from his comments on the self. He mentioned them later in his DIALOGUES CONCERNING NATURAL RELIGION:

QUOTE:

What is the soul of man? A composition of various faculties, passions, sentiments, ideas; united, indeed, into one self or person, but still distinct from each other. When it reasons, the ideas, which are the parts of its discourse, arrange themselves in a certain form or order; which is not preserved entire for a moment, but immediately gives place to another arrangement. New opinions, new passions, new affections, new feelings arise, which continually diversify the mental scene, and produce in it the greatest variety and most rapid succession imaginable.

END_QUOTE

This was a more polished version of his comments from the TREATISE. It was merely a parting shot, because Hume -- apparently to avoid tiresome controversy -- made sure the DIALOGUES weren't published until after his death.

Hume was confounded in his considerations of the self by semantics, and also by the fact that he had effectively no scientific knowledge about the brain available to him. We still don't have a comprehensive understanding of the brain today, but we do know that the "bundle" theory of the mind is backed up by the fact that what we know about the operation of the brain in that it is distributed, parallel, and nonlocalized, not directed from any specific center -- certainly not the pineal gland. Only a small part of our brain is ever activated at one time, with the elements in operation shifting rapidly. Even at that, as noted the brain still uses a considerable amount of energy in its operation; if the whole brain were active at one time, its energy consumption would be unsupportable.

BACK_TO_TOP* Beyond semantics, there are objections to cognitive pragmatism because it discards the element of the magical in human consciousness. Pragmatism asserts that the mind is a manifestation of the mechanistic processes of the brain -- those of perception, thought, and memory. From a scientific point of view, that's no problem at all; indeed it is the assertion of a uselessly inexplicable "magic brain", Harvey, that's a problem, at least if it's taken very seriously. We have a basic understanding of the workings of the brain, but we can observe nothing of this "magic brain". Why is it even supposed to be interesting?

Unfortunately, rejecting dualism raises a storm of protest -- because it undermines the notion of a soul, that the mind reflects a distinct and immaterial spirit that can survive the death of the body. If the mind is strictly a product of the biochemical workings of the brain, there's no soul.

A cognitive pragmatist would have to reply: "Okay, so what?" The difficulty with attempts to reject the material basis of the mind is that it's hard to argue for the nonmaterial, by definition there being nothing tangible there to point to. As the old eerie ditty has it:

I saw a man upon the stair, A little man who wasn't there. He wasn't there again today; Oh, how I wish he'd go away.

Possibly his name is Harvey. The typical argument for the immaterial basis of the mind is that the mind itself is immaterial, and therefore it cannot have a material basis -- it can only exist because of the soul. This is a confusion over the fact that the mind is no more or less than a structured set of behaviors generated by the brain; the brain's a perfectly material thing that can be, say, weighed, but that's obviously not true of the behaviors generated from it. We can observe the behaviors in action, they're material to that extent, but we can't put them on a scale and weigh them.

However, instead of simply dismissing the argument of immaterialism, Hume -- in his tidy essay "On The Immortality Of The Soul" -- characteristically chose to accept it at face value, and then showed it went nowhere. After all, as Hume slyly observed, if it is arbitrarily claimed that material substance cannot support the mind, we have no more or less justification to think that some completely unknown immaterial property could, either:

QUOTE:

Matter ... and spirit, are at bottom equally unknown, and we cannot determine what qualities inhere in the one or in the other.

END_QUOTE

If we arbitrarily declare that some immaterial property can support the mind, then we can just as arbitrarily declare that material substance can, too. We can obtain no logical leverage with such an argument of ignorance.

One major motivation in making a case for an immaterial basis of the mind is to support the notion of life after death. However, even at face value, it doesn't support any such conclusion. What reason do we have to assume that something immaterial is necessarily immortal? Revealingly, few would see cause to argue for an immaterial basis of the mind if it wasn't chained to immortality, since that would reduce any such immaterial principle to excess baggage -- or, more accurately, show that it was always excess baggage.

In his writings, Hume repeatedly noted -- as the central premise of his "skeptical-empirical" philosophy -- that we only know about what demonstrably exists from practical experience. The immortality of an immaterial soul is, as he pointed out, not consistent with any practical experience. We know of no artificial or natural structure that lasts forever. We associate such permanence as we know with items of solidity and durability: diamonds, mountains, planets.

Such enduring objects are also by no means indestructible, and they are static -- unlike a living organism, changing only slowly and gradually through the course of their existence, unless devastated by some accident. When, in contrast, we try to grasp the immaterial, we envision disordered wisps that are evasive and transient in their form and behavior, easily and permanently dispersed. As Hume put it:

QUOTE:

Nothing in this world is perpetual, every thing however seemingly firm is in continual flux and change, the world itself gives symptoms of frailty and dissolution. How contrary to analogy, therefore, to imagine that one single form, seemingly the frailest of any, and subject to the greatest disorders, is immortal and indissoluble?

END_QUOTE

On what basis other than pure speculation can we claim there exists an immaterial structure that is indestructible, immortal? Indeed, isn't the phrase "immaterial structure" a self-contradiction? We could, in reply, claim that only material substance can generate the mind, that the evidently vaporous, unstructured, and fleeting nature of the immaterial prevents it from performing any heavy cognitive lifting, or any lifting at all. "Beings of pure thought / energy" are common props in science-fiction stories, but it's hard to figure out how they're supposed to maintain such a necessarily elaborate organization -- any more than we could figure out how a computer program could be executed with an immaterial computer.

Could we realistically imagine a fire, derived from the destruction of chemical bonds to produce fluctuating and turbulent flows of energy, as possessing anything equivalent to a nervous system, much less a brain? Even if we could show that such a thing is possible, we could hardly claim the fire is immortal; all fires burn out in time. As Hume put it on his deathbed: "It is a most unreasonable fancy that we should exist forever."

Besides, as Hume pointed out, if we can assume the survival of the soul after death, then we can with every bit as much justification believe that it existed before birth. The objection might be raised in reply that we have no verifiable memory of any previous existence; but we know nothing at all of any future existence, either, and one seems no more or less plausible than the other. As Hume said:

QUOTE:

The Soul ... if immortal, existed before our birth; and if the former existence no ways concerned us, neither will the latter. ... Our insensibility before the composition of the body, seems to natural reason a proof of a like state after dissolution.

END_QUOTE

If we dismiss the notion of life before birth -- as most people do, since it's a consideration of no useful consequence -- then why do we take the idea of life after death more seriously?

BACK_TO_TOP* An advocate for the existence of the immortal soul -- a "spiritualist", proposing the existence of intangible spirits and spirit worlds -- will point to the visions of those who have had "out-of-body experiences (OBE)" or "near-death experiences (NDE)" as proof. However, this is making a far-reaching claim on the basis of very weak evidence. British cognitive psychologist Susan Blackmore (born 1951), after undergoing an OBE, decided to scientifically investigate OBEs and NDEs and other "psi" phenomena -- but, as she wrote in 2000, her exercise in "parapsychology" came up zeroes:

QUOTE:

It was just over thirty years ago that I had the dramatic out-of-body experience that convinced me of the reality of psychic phenomena and launched me on a crusade to show those closed-minded scientists that consciousness could reach beyond the body and that death was not the end. Just a few years of careful experiments changed all that. I found no psychic phenomena -- only wishful thinking, self-deception, experimental error and, occasionally, fraud. I became a skeptic.

END_QUOTE

Although Blackmore admitted that she could not prove that OBEs and NDEs were just vivid illusions, in a 1987 article she pointed out the effort to prove they were anything more than that goes nowhere:

QUOTE:

I suggest that, wherever you start in parapsychology, if you base your research on the psi hypothesis, then you will be forced to do ever more and more restricted research, to back up into ever less and less testable positions, and to produce ever more feeble and flimsy buttresses to hold your theory together. In the end, whatever the questions you started with, you are forced to ask more and more boring questions, until there is only one question left: Does psi exist? That question, I submit, is unanswerable.

... All those negative results teach us only one thing, that we have been asking the wrong question. And the whole history of parapsychology looks like a string of wrong questions. Parapsychology is, if it is based on the psi hypothesis, a magnificent failure; not because psi [demonstrably] doesn't exist, but because it asks unanswerable questions.

END_QUOTE

Research -- valid research -- into OBEs show they can be easily induced. Dehaene described an OBE as a kind of "dizziness", a misperception of where we think our body is, relative to where it actually is. NDEs turn out to be similar to the experiences people have when they faint. For example, the perception of "going into a tunnel" turns out to be due to tunnel vision in a brain starved of oxygen, while the "white light" experienced in reports of NDEs is due to spontaneous widening of the pupils, overlighting the retina. It should be noted that most people temporarily near death do not have NDEs; while people who thought they were near death, but were actually not in any serious danger, sometimes do have NDEs.

Spiritualists reject all physical explanations of psi experiences, insisting that the evidence they are "for real" is "irrefutable", even though none of it stands up to skeptical inspection. As Hume put it, "a weaker evidence can never destroy a stronger" -- or as the modern phrase has it, "extraordinary claims demand extraordinary evidence." In the end spiritualists, having only vaporous evidence to support their extraordinary claims, can only shift the burden of proof from themselves, daring the unconvinced to show spiritualism is in error.

The response, of course, is that spiritualism -- by definition, focused on immaterials that are not and cannot be reliably observed, meaning validated by any honest and competent observer -- is unarguable; it's more "magical thinking", it can't be supported or refuted by material evidence. We may believe it is absolutely right if we like, without fear of effective contradiction, but we are no wiser in any specific way if we do believe it. As the physicists also like to say, it's "not even wrong."

* Spiritualists have another issue in that, if there is an immaterial -- undetectable -- soul in control of our behavior, it has to interact with our physical body to get it to perform any actions, and that interaction would be observable. We have observed nothing of the sort, suggesting the soul is literally missing in action. The mind-body problem cuts both ways: if we can't find a bridge from the body to the mind, we can't find a bridge back, either.

More practically, the idea that the mind isn't rooted in the machinery of our brain is undermined by the way our mind is affected by weariness or low blood sugar, both able to reduce us to a stupor. More dramatically, psychoactive drugs can produce profound alterations of our consciousness -- while the minds of schizophrenics, with broken coherence in the stream of thought, are evidently fragmented. More dramatically, unfortunate people with brain damage also have clearly altered consciousness, often in distinctly specific ways corresponding to damage of a particular section of the brain. As the brain suffers from the ravages of age or ailments, the mind becomes more and more tattered and fragmented.

By all evidence, the mind is based on mechanistic processes. There is no credible evidence that the mind is independent in any way of the workings of the brain, much less that our consciousness can survive death. If the mind is based on some undefined and apparently undefinable property -- Harvey -- not associated with the evident workings of our brain, then why are the only things we know to be conscious those that have a properly functioning brain?

To be sure, if people want to believe in an immortal soul, there's no reason to challenge them; they have a perfect right to do so, and what of it? It is of no concern or interest to the sciences. If spiritualists see a dispute over the matter it is, as Hume would put it, "all on their side." Scientists, having jobs to do, have no good reason to be drawn into an argument over whether a pig with wings could fly. Indeed, there is nothing to prevent scientists from believing in an immortal soul themselves, and some do -- though the sensible among them will caution that their spiritual beliefs have no particular relevance to their professional work.

Spiritualists reject cognitive pragmatism and implicitly, often explicitly, embrace dualism, since dualism implies being able to perceive the immortal soul. That's an illusion. We are inclined to believe in dualism because we see a reflection of ourselves in the mind's eye -- but simply because we see ourselves in a mirror, does not mean there's really two entities there. Of course, the deeper irony is that pragmatism does not and cannot rule out the idea that consciousness can survive death; while dualism, in the same way, doesn't do anything to prove it.

It may seem a diversion to discuss the tension between science and spiritualism in a document focused on science. However, there is no place where that tension is stronger than in the study of the mind -- and so, unfortunately, there is no way to avoid the dispute.

BACK_TO_TOP