* In the 1990s, creationism's defeats in court led to the emergence of a new approach to anti-evolution agitation, by resurrecting the Reverend Paley's Natural Theology in modern clothes. Roughly in parallel, creationism began to supplant the traditional thermodynamic / complexity attack on evolutionary science with a revised approach, based on information theory, though it wasn't a real improvement.

* Had creationists simply asserted their views, there would have nothing much of concern in the matter. They had a right to speak their minds, no matter how absurd they might sound, and they had, could have, no effect at all on the workings of science. The problem arose because they were determined to derail the teaching of evolutionary science in public schools.

Following the downfall of the state anti-evolution laws in the 1960s, creationists began to push for laws to mandate "equal time" in teaching MET and creationism in the public schools. The state of Tennessee passed an "equal time" law in 1973, but it was struck down by a Federal Court in 1975 as a violation of the Establishment Clause, since it explicitly required teaching the Biblical account of creation in the Book of Genesis.

The lesson of this bungle having been learned, the ICR's creation science became the tool of choice for pushing anti-evolution teachings in the public schools, and the movement acquired high-profile backers. During the election of 1980, Republic presidential nominee Ronald Reagan publicly referred to evolution as a "theory only" to a group of evangelical ministers, and in 1981 both Louisiana and Arkansas passed laws for the "balanced treatment" of creation science and MET.

The rise of modern creationism led to pushback. The ACLU retained an interest in the matter; it was complemented by the "National Center for Science Education (NCSE)" -- a group based in Oakland, California, associated with the American Association for the Advancement of Science. The NCSE was established in 1983, having emerged from an informal network of local grassroots organizations; its charter was to support science education standards in public schools, keeping an eye out for creationists and other anti-science groups working to undermine them.

The feud over MET had, in short, become much more politically troublesome; politicians who didn't have a particular axe to grind in the issue recognized it for the no-win game it was, and avoided it. Not surprisingly, it ended up in the high courts. Just after Arkansas and Louisiana pushed through their "balanced treatment" laws, the ACLU began lawsuits in Federal court on the basis that the laws violated the Establishment Clause. The Arkansas law was seen as more vulnerable, since it made specific reference to such Biblical matters as a "worldwide flood", with the suit brought against the state in 1981 by a minister, the Reverend Bill McLean. The case was named MCLEAN V. ARKANSAS BOARD OF EDUCATION.

Early in the next year, 1982, a Federal district court judge named William Overton ruled against the Arkansas law, saying that creation science was "inspired by the Book of Genesis" and had no "scientific merit or educational value as science." He dismissed the law as an unconstitutional violation of the Establishment Clause. Overton was a district court judge, and the verdict only applied to his district; the state of Arkansas did not appeal to the Supreme Court, and so that was as far as the ruling went in itself.

However, the fact that the Supreme Court let the ruling stand set a significant precedent. On the basis of the Arkansas ruling, the Louisiana law was summarily dismissed in a pretrial hearing. Backers of the Louisiana law appealed and the appeals process gradually migrated up to the US Supreme Court, the case being named EDWARDS V. AGUILLARD -- Edwin Edwards being the governor of Louisiana, Don Aguillard being a teacher acting as point man for the case. In 1987, Justice William Brennan delivered the verdict for the majority, judging the Louisiana law as an attempt to push a sectarian religious agenda through the school system, concluding: "This violates the Establishment Clause."

The court noted that the ICR, which had backed the creationist case, didn't bother to hide its religious agenda, observing that the organization's charter statement stated that the institute had been founded to meet the "urgent need for our nation to return to belief in a personal, omnipotent Creator." The verdict did agree that there was nothing wrong with "teaching a variety of scientific theories about the origins of humankind", but that such an exercise would need "clear secular intent". There was no way creation science, as it was formulated and practiced, could meet that standard.

* Whatever satisfaction those who approved of the court's decision might have felt at the judgement, it did nothing to stop or even slow down the culture war over MET. In fact, it helped accelerate the growth of private Christian schools, where ICR texts were used in biology classes. The battle over MET in public education didn't go away either, with creationists probing for ways to get their message in, on the dubious belief that all that was required was to find some formula that would be able to squeak by the law.

Figuring out that formula proved much tougher than expected. One tactic was to claim that "evolutionism" was a closet religion, and so its teaching in the schools also violated the Establishment Clause. Jokers suggested there seemed to be an element of desperation in this ploy: having failed to establish creation science as science and not religion in disguise, the only thing left to do was try to establish evolutionary science as religion in disguise in turn. There was also an irony in creationists, in attempting to establish the primacy of religion, portraying religion as the "dirty secret" of MET.

It couldn't work, and it didn't work. A case along such lines went up to the California Supreme Court in 1981, and was shot down. In 1993, a California high school teacher named John Peloza brought a similar suit against his own school on this basis. A Federal circuit court ruled against him in 1994, the judgement concluding bluntly: "Evolutionist theory is not a religion." The reality was that any line of reasoning that could show that evolutionary science was a religion could probably qualify, say, baseball leagues as religions as well. Creationists continued to insist that evolutionary science was a religion, but they no longer had any basis for hope that the courts would buy it.

However, by this time, yet another tactic was in the wings, an effort to provide stickers on biology texts along the lines of:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

This textbook contains material on evolution. Evolution is a theory, not a fact, regarding the origin of living things. This material should be approached with an open mind, studied carefully, and critically considered.

END_QUOTE

The notion had originated in legislation to require teachers to give oral disclaimers -- but since the enthusiasm of teachers in providing the disclaimers tended to vary considerably between science teachers who were sympathetic to creationism and those who hated it, the effort quickly moved on to stickers. Alabama was the first to use the stickers, in 1996, and the idea caught on in other US states. In 2002, after the state of Georgia began to use the stickers, a group of citizens initiated a court case against the practice, claiming it was clearly motivated by religious belief. Parodies circulated of the stickers.

It was actually hard to see anything objectionable in the text of the stickers, with any reasonable scientist perfectly happy to encourage open minds. The problem was that the stickers existed. The same comments were essentially just as applicable to any other branch of science, so why wasn't there an effort to put them on all science textbooks? It was clear the exercise singled out MET for unique scrutiny among the sciences, the only goal being to imply that there was something unusually dodgy about that particular subject, requiring a label somewhat along the lines of that on a pack of cigarettes: WARNING! HAZARDOUS TO YOUR HEALTH!

In 2005, a Federal court ordered the state of Georgia to give up on the stickers -- they still linger in Alabama, it appears only because nobody thought a court challenge over the matter was worth their time. It seemed there was no way to sneak creationism past the courts by dressing it up as science: no matter how spamloaf was served, the courts weren't going to be tricked into thinking it was steak. Judges are used to being doubletalked, they're sensitive to it, and as a rule they don't take kindly to it. It might have been amusing for creationists to throw bafflegab into the faces of scientists in public debates -- but in front of a court of law, the creationists might have done themselves as much good to have soaked themselves with lighter fluid and lit a match. As Harvard paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, a participant in the 1987 Arkansas trial, put it:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

Debate is an art form. It is about the winning of arguments ... [Creationists] are good at that ... But in courtrooms they are terrible, because in courtrooms you cannot give speeches. In a courtroom, you have to answer direct questions about the positive status of your beliefs. We destroyed them in Arkansas. On the second day of the two-week trial, we had our victory party.

END_QUOTE

Having reached a legal dead end, creationists didn't give up, with a faction arising to advocate a new game -- an effort to update Paley's Watchmaker argument, disguised in a modern clothes, labeling the exercise as "Intelligent Design (ID)".

BACK_TO_TOP* The origins of ID can be traced to the 1986 book EVOLUTION: A THEORY IN CRISIS by Michael Denton, a biochemist at the University of Otago in New Zealand. Denton's book was a secular criticism of MET, his skepticism being based largely on the complexity argument. As Denton said in an interview:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

[MET] fails to explain is the apparent uniqueness and isolation of major types of organisms. My fundamental problem with the theory is that there are so many highly complicated organs, systems and structures, from the nature of the lung of a bird, to the eye of the rock lobster, for which I cannot conceive of how these things have come about in terms of a gradual accumulation of random changes.

It strikes me as being a flagrant denial of common sense to swallow that all these things were built up by accumulative small random changes. This is simply a nonsensical claim, especially for the great majority of cases, where nobody can think of any credible explanation of how it came about. And this is a very profound question which everybody skirts, everybody brushes over, everybody tries to sweep under the carpet.

END_QUOTE

Denton here revealed, unintentionally, the basis of the complexity argument in its many forms, in that it was simply an argument of personal incredulity: "I think it's silly, so it can't be true." He also illustrated how creationists necessarily disregard the greater difficulty in proclaiming that organisms must have emerged by magic, or some completely unexplained process equivalent to it. It certainly came as big news in the evolutionary science community that MET was in a state of "crisis" -- or it would have been big news, had much attention been paid to Denton. Not much was, and those who did had no problems recognizing that most of Denton's ideas were stock creationist arguments, sometimes cosmetically disguised.

It was at least realized by those who did take notice of Denton that he wasn't cut from exactly the same mold as the ICR crowd. His criticism was secular, making little or no mention of religion; he had legitimate scientific qualifications; some of his critics thought he raised a few interesting issues; and he was relatively open to feedback. However, he made no lasting impression on the scientific community. He made a much stronger one on the creationist community, which saw his secular read on creationism as having potential.

A decade after the publication of Denton's book, it was becoming apparent to American creationists that the courts weren't going to buy creation science, and a change in tactics was in order. In 1989, a zoologist named Percival Davis and a biophysicist named Dean Kenyon published an anti-evolution textbook named OF PANDAS & PEOPLE to provide an alternative to mainstream, evolution-oriented textbooks. While it was nothing more than a compilation of traditional creationist arguments, in consideration of the obvious hostility of the courts to the term "creationism", it carefully avoided overtly religious language and introduced the term "Intelligent Design" as an alternative term.

Critics eventually managed to find an early draft of the book, revealingly titled CREATION BIOLOGY and littered with explicitly creationist terminology that was replaced with ID terminology in the published version. A draft copy for OF PANDAS & PEOPLE was also found where the replacement of "creationist" in the text by "design proponent" was fumbled, resulting in "cdesign proponentsist".

Although that boo-boo was corrected in the published edition, OF PANDAS & PEOPLE was still heavily criticized for its shoddy scholarship by the science community. OF PANDAS & PEOPLE was not adopted by school boards, but the idea of ID had been introduced.

The concept was picked up by a University of California at Berkeley law professor named Philip E. Johnson, who had "got religion" in the wake of an ugly divorce and become completely opposed to MET. He was highly impressed by Denton's EVOLUTION: A THEORY IN CRISIS, and leveraged off of it in a 1991 book titled DARWIN ON TRIAL.

DARWIN ON TRIAL was, in effect, a law professor's take on creationism. Johnson felt his background as a professor of law qualified him to critique the sciences, since he was formally trained to analyze the logic of arguments and the assumptions underneath them. Unfortunately, he didn't have the background to understand the assumptions, recycling old and flimsy creationist arguments without comprehension of their defects. He certainly failed to appreciate the obvious fact that his background in law gave him as much authority in critiquing science as a scientist would have in critiquing the law -- that is, effectively none.

Aside from the legal colorings, Johnson differed from traditional creationists by assailing the entire basis of science, saying that it was corrupted by its "materialistic bias". In short, he had a problem with the doctrine of the scientific community that asserts that only observable and measurable physical mechanisms can be invoked to explain the natural laws of the Universe, science being based on observations and experiments -- stuff like that. Science, according to Johnson, had gone wrong, and had to be "reformed" of its "materialistic mindset".

Johnson could never clearly explain what his "nonmaterialistic science" was supposed to look like. Had he simply meant that scientists should get religion, that would have been a shrug: scientists had the same right as all citizens to accept or reject religion as they pleased, and which way they went was irrelevant to the standing of their professional work. Johnson went much farther than that, insisting that the sciences could not rightfully ignore the possibility of direct supernatural intervention. That idea was reminiscent of the classic science cartoon -- in which two researchers are standing in front of a blackboard, with clusters of equations on left and right, joined by the text:

AND THEN A MIRACLE OCCURS

One researcher says to the other: "I think you should be more explicit here in step two."

It is, again, not clear if this argument, if it could be called that, was invented by Johnson -- but he certainly popularized it. Creationists began to insist that sciences could not justify the belief that an event had to be in accordance to the laws of nature, that instead, the default assumption was that it had to be due to miraculous intervention.

The argument was absurd. As David Hume pointed out, we cannot prove that the material Universe we see around us is not an illusion -- but no sane person has any real doubt in the matter, and anyone who sincerely does is not likely to be long for this world. It's silly to even ask, it's not a real question. By the same coin, if we accept that the material Universe actually exists, then we also accept that it operates by consistent natural rules. We can't prove that the Sun will rise tomorrow morning, but nobody sane has any doubt it will, or would seriously assert it wouldn't.

If the world were not consistent in its workings, we could learn nothing from experience. In all their practical actions, creationists are as materialistic as everyone else -- observing regular patterns in events and recognizing certain consequences following from actions, in order to get things done. Focusing on the possibility that there may be exceptions to the rules as we have observed them is both unarguable and, given an inability to nail down the exceptions, completely useless. If we argue that the law of gravity may not work all the time, nobody in their right mind would think to jump off a building and expect to be able to fly. However often creationists declared independence from the tyranny of the laws of nature, they could never in practice have any expectation of achieving it.

Johnson was, in effect, attempting to make a case for refusing to learn from experience, in willful indifference to the fact that he could only maintain his anti-materialistic doctrine to the extent that he didn't stake anything he cared about losing on it. On the other side of that coin, to claim that any event, no matter how unprecedented and unexpected, should be recognized as an intervention by an "Unseen Agent" -- ID advocates were generally careful not to say "God", though they found it very difficult not to bring Him into the discussion anyway -- is merely an argument of ignorance:

"We are clueless, therefore Unseen Agent."

"No, we are clueless, therefore clueless."

We could invoke any Unseen Agent we like, and there would be as much evidence to support one as another; that is, no evidence at all. If Johnson wanted to believe in the miraculous, there was no real argument against him doing so -- but it could amount to nothing of substance. He at least admitted that his core agenda was ideological, not technical, claiming that he was simply promoting a point of view, acting as a magnet to people who might be able to put them, somehow, on a firm scientific basis. He was perfectly correct in his belief that DARWIN ON TRIAL would attract the attention of like-minded individuals.

There was substantial interest in the book, leading to a 1992 meeting at Southern Methodist University near Dallas, Texas. At the meeting, Johnson met biochemist Michael Behe of Lehigh University, mathematician William Dembski of Baylor University, and philosopher Stephen Meyer. They formed up an "Ad Hoc Origins Committee" to push anti-evolution ideas, with the group meeting again in 1993 at the California beach town of Pajaro Dunes. The 1993 meeting solidified the group, with Johnson, Behe, Dembski, Meyer, and molecular biologist Jonathan Wells becoming the core of what the ID movement.

In 1995, Johnson published a second book titled REASON IN THE BALANCE, in which he criticized scientific materialism, suggesting as a replacement a "theistic realism" that acknowledge the influence of the Creator in the workings of nature: AND THEN A MIRACLE OCCURS. The next year, 1996, the Seattle-based Discovery Institute -- a conservative think-tank that had been founded in 1990 by Bruce Chapman and George Gilder -- worked with Johnson to set up a branch that would eventually be named the "Center For Science & Culture (CSC)", devoted to ID.

Johnson followed up REASON IN THE BALANCE with his 1997 book DEFEATING DARWINISM BY OPENING MINDS and, in 2003, THE WEDGE OF TRUTH, helping lay the philosophical foundation, such as it was, for the DI's efforts. Johnson eventually went into retirement after suffering a stroke and tiring of the fray, but other "fellows" of the Discovery Institute carried on the fight.

The two most prominent ID advocates were Behe and Dembski. In 1996, Behe published a book titled DARWIN'S BLACK BOX that attracted some public attention. Behe's primary focus was yet another variation on the complexity argument, what he called "irreducible complexity". The idea was that there were biological structures that couldn't lose a single component and still work; according to Behe, it was impossible for irreducibly complex biostructures to have evolved, and so they had to be ID -- creations of the Cosmic Craftsman.

That was nonsense on the face of it. In the first place, any machine that fails completely when it loses any single part is poorly designed; most machines degrade more gracefully than that, and those designed for reliability feature redundancy that allows them to go on working after being significantly damaged. In other words, redundancy is a better sign of ID than irreducible complexity.

More significantly, the implication in saying that irreducibly complex biostructures couldn't evolve was that "reducibly complex" biostructures, featuring redundancies, could evolve. However, in the course of evolution, it is expected that unused elements, not being subjected to selection, have a tendency to genetically "break" and disappear. There was nothing to prevent a reducibly complex biostructure from losing parts of itself, until it couldn't lose any more and still work.

Worse for Behe, he identified a number of biostructures as being irreducibly complex -- but his critics responded with models that showed how all of them could have evolved. He shot back that the models were theoretical, but that was "moving the goalposts": he had claimed that the biostructures had to be the work of the Cosmic Craftsman because there was no possible way they had evolved, but if it could be shown there was a way in principle, his argument crashed and burned.

William Dembski originally caught public attention with his 1998 book THE DESIGN INFERENCE. He constructed a laboriously mathematical "proof", based on information theory, the centerpiece being what he called the "Law of Conservation of Information". It was yet another form of complexity argument, in effect a rethinking of the old and weary SLOT argument. Again, it was hard to say that the idea of using information theory to attack MET was invented by Dembski, but he was the most prominent advocate of the idea, doing much to popularize the notion, with creationists of all persuasions picking up the idea and running with it. Whatever the case -- it went nowhere.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Law of Conservation of Information is based on the notion that the difference between life and non-life is that life has "information". The law itself is usually stated as "information cannot be produced by undirected processes" -- or, equivalently: "Only an intelligence can create information".

It's not really different from the thermodynamic / complexity argument against MET: "An unmade bed never makes itself." As per the Law of Conservation of Information, the information in the human genome that produces a functioning human had to have been produced by an "Intelligent Designer", since it couldn't have arisen on its own. The genome, so the reasoning goes, is something like a computer program, or something like that; computer programs have "information", and since programs don't write themselves, some intelligence had to write them. It's this supposed distinction of "information" that sets up the "magic barrier" between the elaborations of life and non-life: life contains "information"; the natural orderliness of snowflakes isn't a problem because they don't contain "information".

The trouble with the Law of Conservation of Information is that it is, like the SLOT argument against MET, meaningless. It can't be found in any reputable science text, and in fact its credibility is so low that creationists often evasively imply it, instead of coming right out and stating it. An examination of details suggests it's not going to acquire more credibility any time soon, either.

* To come to grips with the supposed Law of Conservation Of Information requires an understanding of definitions from mainstream information theory. The roots of information theory can be traced back to Claude Shannon, an electrical engineer and mathematician who was employed by AT&T Bell Laboratories. After World War II, Shannon was working on the problem of how much telephone traffic could in theory be carried over a phone line. In general terms, he was trying to determine how much "information" could be carried over a "communication channel". The question wasn't academic: it cost money to set up phone lines, and AT&T needed to know just how many lines would be needed to support the phone traffic in a given area. Shannon was effectively laying the groundwork for (among other things) "data compression" schemes, or techniques to reduce the size of documents, audio recordings, still images, video, and other forms of data for transmission over a communications link or storage on a hard disk.

Shannon published several papers in the late 1940s that laid the foundation stones for information theory. He created a general mathematical model for information transmission, taking into account the effects of noise and interference. In his model, Shannon was able to define the capacity of a communications channel for carrying information, and assign values for the quantity of information in a message -- using "bits", binary values of 1 or 0, as the measure, since binary values could be used to encode text, audio, pictures, video, and so on, just as they are encoded on the modern internet.

A message size could be described in numbers of bits, while the capacity of the communications channel, informally known as its "bandwidth", could be described in terms of bits transferred per second. Not too surprisingly, Shannon concluded that the transfer rate of a message in bits per second could not exceed the bandwidth of the communications channel. Shannon confusingly called the actual information content of a message "entropy", by analogy with thermodynamic entropy. The name was from a suggestion by the Hungarian-American mathematician John von Neumann, who noticed a similarity between Shannon's mathematical expression and the statistical definition of thermodynamic entropy.

In hindsight, using the word "entropy" in this context was a dubious idea and the seed of later difficulties. Neither von Neumann nor Shannon realized that they had set in motion endless confusion over the relevance of information theory to physics and other fields of research. In 1961 Shannon himself, confronted with growing chaos, flatly denied that his work on information theory was intended to address "applications beyond communications channels" and that it was not "necessarily relevant" to any other fields. It might have applications in other fields, it might not, but Shannon could say nothing of substance about such applications. In any case, Shannon's "entropy" might be much better described simply as the "quantity of information", at least to save everyone a lot of exasperation.

Noise, in Shannon's model, wasn't distinct from a message -- they were both information. Suppose Alice is driving across country from the town of Brownsville to the town of Canton. Both towns have an AM broadcast radio station on the same channel, but they're far enough apart so that the two stations don't normally interfere. Alice is listening to the Brownsville station as she leaves town, but as she gets farther away, the Brownsville station signal grows weaker while the Canton station signal gets stronger and starts to interfere -- the Canton broadcast is "noise". As she approaches Canton, the Canton broadcast predominates and the Brownsville broadcast becomes "noise". To Alice, the message is the AM broadcast she wants to listen to, and the unwanted broadcast is "crosstalk", obnoxious noise -- not categorically different from and about as annoying as the electrical noise that she hears on her radio as she drives under a high-voltage line.

As far as Shannon was concerned, the only difference between the message and noise was that the message was desired and noise was not; both were "information", and there was no reason the two might not switch roles. In Shannon's view, message and noise were simply conflicting signals that were competing for the bandwidth of a single communications channel, with increasing noise drowning out the message.

* Shannon's mathematical definition of the amount of information is along the lines of certain data compression techniques -- "Huffman coding" and "Shannon-Fano coding", two different methods that work on the same principles. His scheme involves taking all the "symbols" in a message, say the letters in a text file; counting up the number of times the symbols are used in the message; assigning the shortest binary code, say "1", to the most common symbol; and successively longer codes to decreasingly common symbols. Substituting these binary codes for the actual symbols produces an encoded message whose size defines the actual amount of information in the message.

The Shannon definition of information is workable, but not as general as might be liked -- so two other researchers, the Soviet mathematician Andrei Kolmogorov and the Argentine-American mathematician Greg Chaitin, came up with a more general and actually more intuitive scheme, with the two men independently publishing similar papers in parallel. Their "algorithmic" approach expressed information theory as a problem in computing, crystallizing in a statement that the fundamental amount of information contained in a "string" of information, is the shortest string of data and program to permit a computing device to generate that string.

To explain what that means, Kolmogorov-Chaitin (KC) theory defines strings as ordered sequences of "characters" of some sort from a fixed "alphabet" of some sort -- the strings might be a data file of Roman text characters or Japanese characters; or the color values for the picture elements (picture dots, "pixels") making up a still digital photograph; or a collection of basic elements of any other kind of data. As far as the current discussion is concerned, the particular type of characters and data is unimportant.

The information in a string has two components. The first component is determined by the total quantity of information encoded in that string. This quantity of information is dependent on the randomness of the string; if the string is nonrandom, with a structure that features repeated characters or other regularities, then that string can be compressed into a shorter string. This component of information is the length of the smallest string into which the original string can be compressed.

Consider compressing a data file. If the file contains completely random strings, for example "XFNO2ZPAQB4Y", then it's difficult to get any compression out of it. However, if the strings have regular features, for example "GGGGXXTTTTT", they can be compressed -- for example, by listing each character prefixed by the number of times it's repeated, which in this case results in "4G2X5T". This is an extremely simple data compression technique, known as "run-length limiting (RLL)", but more elaborate data compression schemes work on the same broad principle, exploiting regularities -- nonrandomness -- in a file to reduce the size of the file.

The second component is defined by the size of the smallest program -- algorithm -- to convert the string. To convert the string "GGGGXXTTTTT" to the string "4G2X5T" requires a little program that reads in the characters, counts the number of repetitions of each character, and outputs a count plus the character. To perform the reverse transformation, a different little program is required that reads a count and the character, then outputs the character the required number of times. The sum of sizes of the compressed string and the programs gives the information. Smarter programs using a different compression scheme might be able to produce better compression, but a smarter program would tend to be a bigger program: We can't get something for nothing.

* What Shannon was trying to do in establishing information theory was to determine how big a message could be sent over a communications channel. He had no real concern for what the message was; if somebody wanted to send sheer gibberish text over a communications channel, that was from his point of view the same as sending a document; noise was simply information other than the message that was supposed to be sent over the channel. The amount of information in the message only related to the elaboration in the patterning of the symbols of the information. The content of the message -- its "function" or "meaning", what it actually said -- was irrelevant.

In KC theory, the amount of information was defined as the best compression of this information, along with the size of the programs needed to handle the compression and decompression. The compression of the information increased depending on how structured or nonrandom the information was -- for example, if the information was very repetitive, it could be compressed considerably. If it were highly random, in contrast, it wouldn't compress very well.

Notice that in this context, "information" can be "nonrandom" or "random" -- "information" and "random" are not opposed concepts. In addition, "messages" and "noise" are simply information, the first wanted and the second not, and either can be "nonrandom" or "random" as well.

In summary, as far as mainstream information theory goes, the answer to the question: "How much information is there in a file?" -- is very roughly: "How much disk space does the file take up on a hard disk after it's been compressed?" What does this say about what's in the file? Nothing; anything could be in the file, doesn't matter whether it makes the slightest sense or not, the compressed file size defines the amount of information in it.

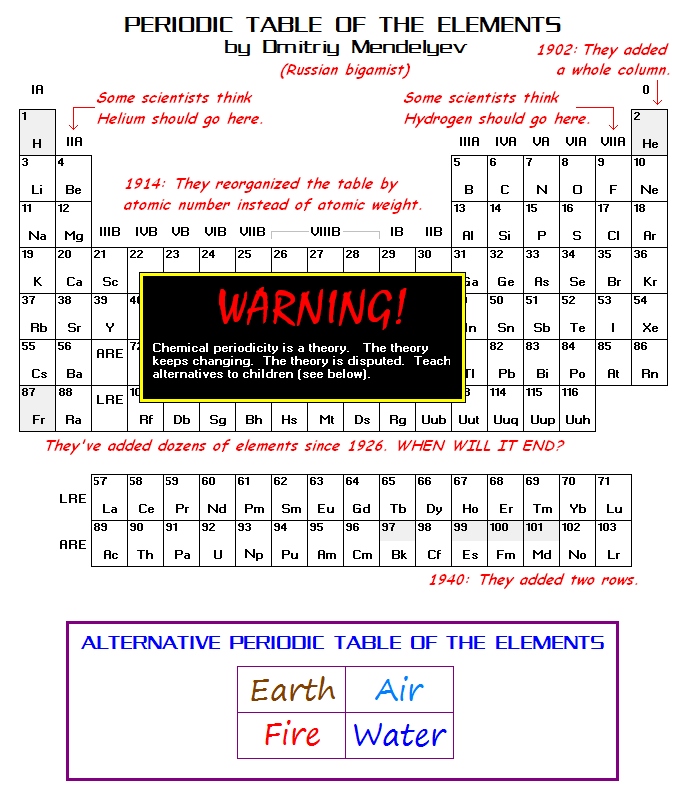

BACK_TO_TOP* The KC scheme is an abstraction; of course, practical examples mean real-world implementations of compression schemes. Let's consider the PNG image-file format used on the internet -- which uses a two-dimensional variation on RLL to achieve compression -- as an approximate practical tool. Under the definition of KC information, the size of the image file after going through PNG compression isn't exactly the information -- for one thing, there's no consideration in that of the size of the compression and decompression programs to do the job -- but there's no real problem in saying that the size of various image files after going through PNG compression can provide a measure of their relative amounts of information.

In any case, converting an uncompressed image file, such as a BMP file, to PNG can result in a much smaller file. However, the amount of compression depends on the general nature of the image. A simple structured image, for example consisting of a set of colored squares, is highly nonrandom and gives a big compression ratio -- a casual way of putting this is that the image contains a lot of "air" that can be squeezed out of it. A very "busy" photograph full of tiny detail is much more random and doesn't compress well. An image consisting of completely random noise, sheer "static", compresses even more poorly. Consider the following image file, containing a simple pattern:

-- and then a file containing a "busy" photograph of a flower bed:

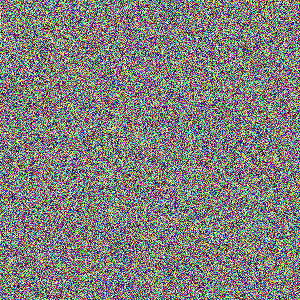

-- and finally a file containing sheer meaningless noise:

All three of these image files are full color, and have a resolution of 300 by 300 pixels. In uncompressed BMP format, they all are 263 kilobytes (KB) in size. In compressed PNG format the first file, with the simple pattern, is rendered down to 1.12 KB, less than half a percent of its uncompressed size -- a massive compression, not surprising since the image is mostly "air". The second file, with the flower bed, compresses poorly, down to 204 KB, only 78% of its uncompressed size. The third file, with the noisy pattern, does worse, compressing to 227 KB, 86% of its uncompressed size. It might seem that the third file wouldn't compress at all, but random patterns necessarily also include some redundancy, in just the same way that it's nothing unusual to roll a die and get two or more sixes in a row -- in fact, never getting several sixes in a row would be in defiance of the odds. Purely random information can be compressed, just not very much.

In any case, the bottom line is: which of these three images contains the most information? As far as information theory is concerned, it's the one full of noise. The intuitive reaction to that idea is to protest: "But there's no information in the image at all! It's pure gibberish!"

To which the reply is: "It is indeed gibberish, but that doesn't matter -- or to the extent that it does matter, it has lots of information because it's gibberish. The information content of the image is simply a function of how laborious it is to precisely describe that image, and it doesn't get much more laborious than trying to describe gibberish."

BACK_TO_TOP