* In the summer of 1941, Hitler's armies invaded the Soviet Union and sent the Red Army reeling back in a series of staggering defeats. The catastrophe was a bloody testament to Josef Stalin's foolishness.

* Following his decision to invade the Soviet Union, Hitler began a major expansion of the Wehrmacht. By the jump-off date for BARBAROSSA, there would be almost 4 million soldiers in the ranks and over 150 divisions. This expansion in particular increased the number of panzer divisions from ten to twenty. However, there had been no coordinated tank production plan, and the number of tanks in each of these twenty divisions was only two-thirds of the numbers in the earlier ten divisions. The average number of tanks in the panzer divisions available for BARBAROSSA was 125, and production of newer and heavier tanks was not enough to compensate for the dilution of numbers. Most of the tanks available were the Panzer Mark IIIs and Mark IVs, as well as the light Czech 38 tank. Their guns of all these tanks lacked hitting power. Similarly, German anti-tank guns would also prove to be too light.

In addition, the panzer divisions needed about 3,000 trucks to transport infantry, ammunition, and supplies, and trucks were in limited supply, particularly since motorized infantry divisions needed many trucks as well. Captured French trucks were used to stretch the limited stocks, though the French vehicles were not very rugged. There was a shortage of tires as well. Much of the logistical support for the infantry divisions for BARBAROSSA was to be provided by 625,000 horses; the German Army was still far from a fully mechanized force, with the restricted mobility of infantry formations and particularly the weak logistical capability amounting to a brake on offensive operations.

The Luftwaffe was also strained to support the operation. While the Luftwaffe had obtained brilliant successes in the early campaigns of the war, it had been badly cut up during the Battle of Britain and aircraft production had not been rapid enough to make up the shortfall. There were no more aircraft available than there had been to support the invasion of France and the Low Countries. Hitler could judge his forces adequate to the task, but not more than that; BARBAROSSA was a throw of the dice, based on an optimistic forecast of events. If the optimistic forecast proved incorrect, German prospects for success would be diminished in proportion to just how incorrect they were.

The quality of German soldiers, however, was not to be doubted. They had won victory after victory, were very confident, highly trained, and well led. The Wehrmacht was, man for man, one of the best fighting forces in the world. Unfortunately, the rapid expansion of the military meant that the traditions of the old officer corps had been diluted. Many of the new young officers were dedicated Nazis and shared Hitler's crackpot bigotries. They would quickly descend to senseless brutalities in the campaign against the Slavic hordes to the east.

* On paper, the Red Army was impressive, with 4.5 million men and 23,000 tanks. In practice, much of its equipment was obsolete, and as the disastrous Winter War in Finland had proven, its organization and leadership were very poor. Stalin's purges had taken a military organization with innovative and professional leadership and all but wrecked it. With war with the Germans looming, the Red Army scrambled to reorganize. Crash programs were instituted to improve the quality of the new officers who had been so hastily promoted to fill the vacuum at the top. In a tacit acknowledgement of the indiscriminate foolishness of the purges, 4,000 officers who had been purged were pulled back in from the Gulag or from punitive-duty posts.

Stalin had disbanded the Red Army's large-scale mechanized formations in 1939, dispersing its armor among infantry divisions. The German victories in Poland and the West had proven that decision unwise, and the mechanized formations were hastily thrown back together. They were mostly equipped with the fast but lightly-armored BT-7 tank, which could be taken out by any German anti-tank weapon. A much improved successor, the T-34, was going into production, but it wouldn't be available in numbers for some time.

By the spring of 1941, the Red Army's reorganization was still woefully incomplete. Only 30% of Soviet tanks were fully operational. Motor transport was in short supply, as was artillery ammunition of all types, as well as radios. The Red Air Force, the VVS, was also overburdened with obsolete equipment, and suffered from poor maintenance and equipment shortages. Pilot training was sketchy at best, since the flight schools were overloaded, under-equipped, and did not have enough experienced instructors.

Soviet military planning, which almost entirely reflected the wishes of Stalin, did not acknowledge the possibility of a German invasion in the immediate future. However, a war with the Germans was seen as likely over the long run and some preparations were made. Stalin built up stockpiles of food, strategic metals, and oil. He also built up industrial centers east of the Urals, where they would be out of reach of Hitler in case of an invasion.

Stalin refused to listen to suggestions that the strategic stockpiles be moved east of the Urals as well. That was part of a larger controversy over the positioning of Red Army forces. One school of thought favored placing them near the USSR's borders, while another school wanted them placed farther in the interior, where they would have more time to react to an attack.

In 1936, the Soviet Union had begun work on an extensive series of fortifications, known as the "Stalin Line", to protect the USSR along a line from the Baltic to the northern side of the Pripet Marshes. In 1941, the Stalin Line had become a formidable obstacle to an invader, though it was by no means continuous, but after the USSR's seizure of new territories to the west the Stalin Line stood well east of the Soviet Union's new borders. Stalin insisted that the Red Army leave their existing fortifications, move up to the new border, and dig in there. He felt that the advantages of a forward position outweighed the loss of the fortified line.

Many of Stalin's generals disagreed. They knew that building up new defenses would take time, and even if the defenses were complete, the Germans would be able to fall on them swiftly and with a high degree of surprise. Connections to rear supply areas were uncomfortably long; there were inadequate mobile forces in the rear to counter a German breakthrough; and the Red Army was not well trained in mobile tactics anyway, making the advantage of extra space questionable. A more rational scheme would have been to deploy light "tripwire" forces at the border to provide an alarm of an attack and delay it, with the bulk of the forces to the rear. Stalin did not agree, and arguing with him could be dangerous. The Red Army did what they could to dig in at their new forward positions.

* In January 1941, Georgiy Zhukov had helped direct elaborate war games that were conducted by the defense commissar, Marshal Timoshenko. Zhukov's forces played the role of attacker; in the games, his attackers had wiped out the defenders and penetrated deep into Soviet territory. Stalin was pleased with Zhukov and promoted him to the position of chief of general staff.

Zhukov was well-versed in the theory and practice of war. He was tough, competent, energetic, ruthless, and intolerant of failure in his subordinates. He was not liked, referred to by many as the "Zhuk (beetle / cockroach)" as a descriptive pun on his name, but he was generally respected. Most Soviet generals believed in an active defense, and Zhukov was no exception. It was the formula that had brought him victory at Khalkin Gol: stay on the defensive, build up forces in secret, and then hit the enemy with a massive counterstroke. He disagreed with Stalin's policy of basing the Red Army along the borders, and wanted to retain large and powerful forces well into the interior of the country. However, although Zhukov was inclined to the outspoken and showed no evident fear of Stalin, Zhukov he still knew better than to press the matter.

* Hitler had originally scheduled that BARBAROSSA begin on 15 May, and by the beginning of May nearly 80 divisions were in place. Their movements had been concealed by an elaborate campaign of misinformation and deception. Forward airfields had been built in secret, and vast stockpiles of fuel, ammunition, and supplies had been quietly set up near the jumping-off points. Despite all the effort, the plan was running behind schedule. The winter of 1940:1941 had been unusually long, leaving roads in the frontier regions muddy and difficult to use. Stocks of trucks remained inadequate. A delay seemed increasingly likely.

Then the delay became inescapable. On 28 October 1940, Italy had invaded Greece, but the Greeks put up a stiff fight and threw the Italians back to Albania, an Italian colony. The British sent an expeditionary force to help the Greeks. Hitler could not tolerate the presence of the British in the Balkans, since they threatened the Rumanian oil fields that provided the Reich's fuel supply; Greece had to be conquered, and the British driven out.

Hitler did not think that the capture of Greece would be difficult or time-consuming, particularly since Yugoslavia was in league with the Reich, having signed a friendship treaty on 25 March 1941. Given Yugoslav cooperation, German troops would be able to reach the border of Greece without obstruction. However, on 27 March, the anti-German faction in Yugoslavia, encouraged by British agents, overthrew the pro-German government, with the new regime signing a friendship treaty with the USSR on 6 April. Stalin wanted to show the Reich that the Soviet Union would protect its interests in the Balkans; the Fuehrer saw the Kremlin's actions in Yugoslavia as just one more good reason to crush the USSR.

On 6 April, with the ink on the friendship treaty between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union barely dry, powerful German formations invaded both Yugoslavia and Greece. The USSR hastily repudiated its friendship treaty. The campaign in the Balkans committed the Reich's military forces, and so BARBAROSSA would have to wait until the operation was complete, being postponed to 22 June. Some have claimed that this delay doomed the assault on the USSR from the outset -- but as discussed above, simple logistical difficulties had made a delay likely in any case. Hitler's generals certainly did not protest that the postponement had fatally compromised the plan.

Besides, BARBAROSSA was based on strategic intelligence that would turn out to be very wrong; Hitler was biting off more than he could chew, and it is hard to demonstrate that the delay in the start of the campaign made a decisive difference in the future course of events. In fact, the postponement of the start of BARBAROSSA helped put the Soviets off their guard: their intelligence had obtained warnings of a German invasion of the USSR in May, but it hadn't happened, the result being that later intelligence reports indicating an invasion were discounted.

In any case, Yugoslavia was overrun in 12 days. Stalin, fearful of Hitler, sat by and watched. Belgrade, the capital, was heavily bombed by the Luftwaffe, with large numbers of civilians killed. The conquest of Greece took another two weeks. By the end of April 1941, survivors of the British expeditionary force in Greece had been evacuated by sea. Thousands of British soldiers were taken prisoner, and most of the expeditionary force's heavy equipment had to be left behind.

As the Wehrmacht completed mop-up operations in the Balkans, armor and headquarters units began to move northwards back to jump-off points in Rumania, Poland, and East Prussia. Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft worked overtime in flights over the western parts of the USSR to provide precise maps of Soviet military assets that the offensive would need to wipe out. Stalin ordered that nothing be done to interfere with the overflights; there are tales that in a few cases Luftwaffe aircraft suffered engine trouble and landed at Soviet airfields, where they got repairs and fuel, to be sent on their way with a friendly pat on the back.

* The large numbers of Luftwaffe reconnaissance overflights should have alerted Stalin, and the massive German troops movements could hardly be concealed. Hitler glibly told Stalin that he was sending troops to Poland to keep them out of reach of British air raids, and as misdirection to keep British intelligence in the dark about the "plan" to invade Britain. Stalin was also receiving surprisingly detailed hints from other quarters. In February, a German who was working at a printing firm passed the Soviet embassy in Berlin a copy of a German-Russian phrasebook that his employers were printing in large quantities for the German Army. Phrases included items such as: "Hands up or I shoot!"

On 1 March Sumner Welles, the American undersecretary of state, had handed the Soviet ambassador to the USA, Konstantin Oumansky, a detailed document outlining Hitler's invasion plans, obtained by the US embassy in Berlin from anti-Nazi Germans. Oumansky was staggered to find out that the Americans had obtained the intelligence back in August 1940, and had run it through careful validation to ensure its authenticity before passing it on to the Soviets. Welles commented later that Oumansky went pale when he realized what he was being told.

In April, Winston Churchill tried to pass on intelligence about the threat to Stalin through Sir Stafford Cripps. Neither Stalin nor Molotov were interested in talking to Cripps, and he simply ended up submitting his report through normal bureaucratic channels. Of course Stalin had every good reason to be suspicious of the British and their American backers, who had a very strong and obvious interest in turning him against Hitler. Unfortunately, Stalin's suspicions were getting the better of him.

On the night of 10:11 May 1941, Rudolf Hess -- the Nazi Party deputy and a close confidant of the Fuehrer -- stole a Messerschmitt Bf 110 twin-engine fighter and flew to Scotland, where he parachuted to earth, telling his captors he had come to negotiate a settlement between the Reich and Britain. He was deluded: the British simply threw him into prison, where he would remain for the rest of his life. Both the British and the Reich made it publicly clear that Hess, who had long been regarded as eccentric in Nazi Party circles, had gone off the deep end, and there was nothing more to it than that. Churchill later summed up Hess's mission as a "completely devoted and frantic deed of lunatic benevolence."

Instead of concluding that the story was too crazy to be a lie -- no matter how it was read, it seemed like a bizarre way to conduct secret diplomacy -- Stalin concluded that it was too crazy to be the truth, and became thoroughly obsessed with the incident. The agreement between the denials between the British and the Germans, who much more normally told exactly opposite stories on any matter, must have seemed suspicious, while the implications of a deal between the two were obviously fearsome. A deal with Britain implied that Hitler could then turn all his unwanted attention on the USSR.

Koba concluded that Churchill's attempts to warn about looming danger were intended to provoke the USSR into mobilization that would give the Germans a pretext to invade. Stalin's thinking seemed to have fallen into the haywired logic of a conspiracy paranoid, with historians later trying, with little success, to puzzle out what he was thinking. Were Britain and the Reich working on a deal that would give the Fuehrer a free hand in the East? Even if such a deal was struck, could Hitler really trust that the British wouldn't knife the Reich in the back after Germany invaded the USSR? Besides, the Germans were obtaining clear benefits from their alliance with the USSR, why would they have wanted to upset the applecart? The Germans did seem inclined to shake the applecart, but he didn't believe they wanted to tip it over; Stalin liked to use bluff and bluster as a pressure tactic in his diplomacy, certainly Hitler did as well.

Stalin did not think that Hitler was too scrupulous to attack the USSR. Stalin had no scruples, and had not the slightest belief that Hitler had any either -- but Stalin thought that Hitler had no immediate motive for attacking the USSR. Stalin failed to realize that there was a major difference between him and Hitler. Stalin really had no vision beyond the accumulation of power, while Hitler was, in his own ugly way, an idealist. Hitler might make a pact of convenience with Stalin, but Hitler saw the Jewish Bolshevik conspiracy as all that was wrong with the world, and he wouldn't sleep well until he had stamped it out. The Fuehrer didn't need a pretext to attack the USSR.

It is now impossible to reconstruct exactly what was going on in Stalin's mind, but it is certainly clear that his emphatic certainties were reflections of deep confusions. Of course Hitler was doing what he could to enhance those confusions, for example leaking fake plans for the invasion of Britain and other countries; in a particularly ingenious ploy, tales were leaked that the Fuehrer planned to present the Soviet Union with a set of demands, as he often did before taking action, misdirecting Stalin away from the thought of an attack without warning.

Under the circumstances, it is not so surprising that Stalin didn't just ignore American and British intelligence; but he also ignored his own intelligence. Richard Sorge, an important Red spy placed in the German embassy in Tokyo, reported on 12 May 1941 that an invasion with 150 divisions would jump off on 20 June. Sorge sent a correction on 15 May, saying the invasion would begin on 22 June. Sorge's reports were ignored, as were other intelligence warnings. NKVD head Lavrenti Beria ordered that agents who provided such reports were to be dealt with harshly for supplying "disinformation". Soviet intelligence officers were reluctant to inform the leadership of what might be interpreted as bad news in the first place; now they were being told in specific terms that bad news was unwelcome.

The German ambassador to the USSR, Count von der Schulenberg, was not fond of the Nazis and believed that a German attack on the Soviet Union would be a disaster. He even warned a high Soviet official of preparations for the invasion over lunch. Stalin's only reaction was outrage: "Disinformation has now reached the ambassadorial level!"

By June, not only were Luftwaffe overflights providing disturbing hints that something was about to happen, German diplomats were sending their families home and canceling orders for goods and services, while German ships were clearing out of Soviet ports. If such matters were drawn to Stalin's attentions, he disregarded them. A report released by the state TASS news agency on 14 June flatly denied that there was any truth to rumors that Germany was preparing to attack the USSR and implicitly labeled the rumors as British and American lies, "devoid of all foundations". Stalin was apparently hoping the Germans would step forward and denounce the rumors as well. If so, he was unpleasantly surprised when they didn't. Unfortunately, Red Army officers took the TASS report at face value and dropped their level of readiness.

On 16 June, Stalin received a detailed report on BARBAROSSA obtained from a Red spy in the Luftwaffe command structure, passed on from a Red agent in Switzerland named Alexander Foote. The report was angrily rejected, Stalin saying the spy should "go fuck his mother". On 18 June, a German soldier came across Soviet lines. He was the son of a Communist and pro-Soviet, and after he had got drunk and struck an officer, a serious offense, he had decided to desert. He told them the invasion would begin on the morning of 22 June. When his captors were skeptical, he told them they could shoot him if it didn't come true.

It appears that Stalin did recognize the possibility of an attack. Some measures to increase preparedness were taken as the first day of summer approached, but he was so determined to pursue a policy of appeasement and stalling for time that he simply let down his guard. He had completely suppressed dissent or even discussion, and had no reality checks to tell him that it was time to stop doubletalking and prepare for a fight. Late on 21 June, Stalin finally began to turn around, putting some forces on alert, though he remained cautious and very tentative. Red Army forces were not to return fire if provoked. It was far too late, and the orders did little more than confuse front-line commanders.

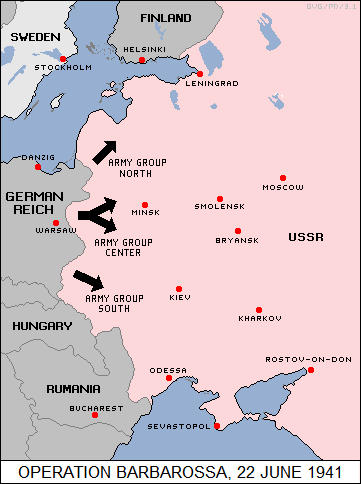

BACK_TO_TOP* On 21 June 1941, three million German soldiers had assembled at jumping-off points along the Russian border in preparation for BARBAROSSA. German infantry divisions had been in place since the beginning of the month, to be then bolstered by motorized and armored divisions. The German forces were organized into Army Groups South, Center, and North, supported by a total of 2,400 tanks, 6,000 artillery pieces, and 2,500 aircraft:

The USSR had 2,900,000 men on the western frontier, as well as 15,000 tanks and 9,000 aircraft. Reinforcements were being moved up as well -- but the numbers were misleading, Soviet forces were still very poorly prepared for serious combat. The USSR was dangerously vulnerable, though at the same time the vast numbers of men and equipment hinted of the resources that the Soviet Union might be able to call upon when pressed.

The western regions of the USSR were divided into four main military regions: Baltic, Western, Kiev, and Odessa regions, which would be renamed "Fronts" in the next few days:

In addition to these forces, four armies with 114 divisions were in the process of moving west as reinforcements. Each front also had a VVS aviation component for air support.

* Early in the morning of Sunday, 22 June 1941, Soviet troops in the frontier regions were awakened by heavy incoming artillery fire. The barrages were precisely pre-targeted and methodically destroyed Red Army military assets near the border. Specially trained Wehrmacht assault groups swept over Soviet border guards, wiping them out methodically and securing bridges and other strategic points along the border. One group of German border guards at a bridge eliminated their Soviet counterparts on the other side by the simple measure of asking them to come out for a discussion, then gunning them down.

The Luftwaffe conducted massive strikes far behind the border, in particular targeting Soviet airfields. Most of the Red aircraft were caught on the ground. German troops and tanks rolled into the Soviet Union over the full length of the frontier. Frantic calls for help from Red Army units under the hammer went unheeded in the chaos. One such plea received the famous response: "You must be insane. And why isn't your message in code?"

As reports poured in, Zhukov phoned Stalin, who was in his dacha (country house) outside Moscow. The phone rang and no one answered it. Zhukov let it ring. A duty officer answered, and finally Stalin came to the phone. Zhukov explained the situation and asked for permission to return fire. Stalin, numbed, said nothing. Zhukov asked: "Have you understood me?" Stalin said nothing.

Stalin remained muddled for hours, and the order to return fire was not issued until 07:15 AM. In the meantime, the Germans swept forward rapidly, overwhelming Soviet border units that had received no orders for dealing with the situation. Without orders, they could do nothing, for Stalin had eliminated nearly all officers who dared to take initiative on their own. Stalin was so unstrung that Molotov had to announce, later that day, the news of the invasion to the Soviet people: "Without any declaration of war, German troops have attacked our country, attacked our borders in many places, and bombed our cities with their aircraft."

Goebbels had read off a speech written by Hitler to the German people that morning, predictably declaring that war was required to "counter this conspiracy of the Jewish-Anglo-Saxon warmongers and the equally Jewish rulers of the Bolshevik headquarters in Moscow." The action was justified, Goebbels explained, because the Soviets had been planning to attack Germany.

To be sure, had Stalin felt he had the capability he might well have taken on Hitler first, but as discussed the Red Army was in no condition to do so. Nazi apologists would later insist that the USSR was in fact planning to attack Germany, using a Red Army plan dated 15 May 1941 as evidence, but this was a defensive plan that simply considered the option of preemptive action in the face of an imminent German attack. Apparently when Zhukov presented the plan to Stalin, Koba had shot back: "Are you mad? Do you want to provoke the Germans?"

Soviet soldiers and civilians fled the invasion in panic, with refugees clogging roads and helping contribute to the confusion. Large numbers of troops surrendered without a real fight. Red Army units were in chaos, lacking clear orders -- partly due to confusion at the top; partly due to the destruction of communications centers by Luftwaffe bombers, as well as sabotage by German Army infiltration teams and ethnic nationalist saboteurs who had been trained by the Germans.

In the first two days of the attack, the Luftwaffe destroyed roughly two thousand Soviet aircraft, many of them lined up neatly along the runways of air bases that were sited too far forward. They were easy targets for surprise attacks, with the Germans plastering the fields with fragmentation bombs and then strafing them for good measure.

Those pilots who did get off the ground were no match for the Luftwaffe. Although the Soviet Union had accelerated the development of more modern aircraft over the previous few years, the standard Red Air Force fighters were the barrel-shaped Polikarpovs, the biplane I-153 and monoplane I-16, both maneuverable but outdated, not the match of the German Messerschmitt Bf 109 -- with the Luftwaffe now equipped with the much-improved Bf-109F variant. Soviet air-combat doctrine was equally behind the times, with fighter pilots flying in rigid formations that hobbled their freedom of movement and left them easy targets. Soviet aircraft were shot down so easily that one Luftwaffe general termed it "infanticide". Even Reichsmarshal Hermann Goering, boss of the Luftwaffe, was incredulous at the numbers of Soviet aircraft destroyed, and ordered intelligence to perform a recount. The numbers came back bigger.

Fighting raged all up and down the frontier, but the heaviest blows were delivered by German Army Group Center, falling on three Soviet armies of the West Front and one army of the Northwest front. The immediate German strategy was to use infantry divisions to seal off Soviet forces in a salient centered on the border city of Bialystok, while panzer divisions expanded the enveloping movement deep into the Soviet Union towards Minsk, a key rail junction and on the main highway to Moscow.

Red Army leadership was ineffective in the face of the catastrophe. On the evening of 22 June, Defense Commissar Marshal Timoshenko sent an order from Moscow to the armies in the frontier regions to begin an immediate counteroffensive and sweep the enemy out of Soviet territory. In reality, these armies were being hard-pressed to even survive and were in no condition to think about offensive action. Soviet reserves were still being called up, and there was no overall operational plan. Protests were useless and few generals even tried to make them, leaving Moscow even more ignorant of the extent of the rapidly expanding disaster.

General Pavlov could only fall back on lessons learned in wargames conducted in January to perform counterattacks. With his supply system shattered, communications badly disrupted, and the Luftwaffe in complete control of the skies, his efforts accomplished nothing. On 27 June, German panzer divisions closed the ring in their envelopment maneuver, meeting near Minsk. Soviet forces inside the trap were doomed. The Germans had penetrated 320 kilometers (200 miles) into the USSR in only five days. They were a third of the way to Moscow.

The only thing that Moscow had done in response to the invasion was to set up a new command structure, in the form of a general headquarters organization known as the "Stavka", created on 22 June. The name was, interestingly, an old Tsarist term. Above that was the "State Defense Committee", known by its Russian acronym GOKO, which included Molotov, Beria, Voroshilov, and Georgiy Malenkov. Of course, neither group had any capability, or for that matter desire, to defy Stalin, who could countermand their orders and override them as he liked.

* In the meantime, German Army Group North was pouring across the river Nemen. Soviet armor counterattacked, but within four days these forces had been encircled and destroyed. Other German forces had seized bridges intact over the Dvina at Dvinsk, by the subterfuge of sending Germans in captured Soviet trucks with the drivers in Red Army uniforms to grab on and hold until heavier German units arrived. There was no further natural obstacle to block the Germans in their drive on Leningrad, and Soviet defenses in their path were disorganized. However, much to the fury of Army Group North's panzer commanders, the tanks were told to stop and wait for the infantry units to catch up.

German Army Group South was not having the same good luck as the other two groups. Soviet commanders in the south had been able to react more effectively to the invasion, and Red Army units there were able to mount more substantial resistance, inflicting serious though not crippling casualties on the invaders. The Soviets also had many more tanks than the Army Group South. Stalin was also slowly beginning to understand that the USSR could afford to sacrifice land more easily than armies, and was starting to authorize withdrawals when he was convinced they were absolutely necessary.

Along with offensive thrusts by other forces, Army Group South's Panzer Group 1, with 600 tanks, penetrated rapidly towards the town of Brody. Five armored corps of the Soviet Southwest Front, with over a thousand tanks, counterattacked on 26 June, attempting to cut off Panzer Group 1 and link up at the town of Dubno. One of the Red Army corps commanders was told by a political commissar: "If you occupy Dubno by this evening, we will give you a medal. If you don't, we will shoot you."

The result was a furious battle that lasted for four days. In particular, German tank and antitank gun crews found the new heavy KV tank and the medium T-34 tank a nasty surprise; the KV was big and unreliable, somewhat more intimidating than effective for the moment -- the "KV" stood for "Kliment Voroshilov", incidentally -- but the T-34 was a force to be reckoned with. The standard German 37-millimeter antitank gun was ineffective, the shells simply glancing off. Unfortunately, the Soviets did not use their armor wisely, and the Germans were able to isolate these monsters and destroy them at close range. Worst of all for the Red Army, the Luftwaffe had total air supremacy and destroyed Soviet tanks at will.

Panzer Group 1 took a severe battering during the battles around Dubno but survived. In contrast, the main armored elements of the Red Army's Southwest Front were all but completely wiped out. After a week of victories, Hitler and the Wehrmacht had every reason to be pleased with themselves. Some predicted that Moscow would fall within two more weeks. Hitler crowed that "the Russians have lost the war." Much the same opinion was widespread in London and Washington.

BACK_TO_TOP* Stalin's response to these calamities remains difficult to decipher, historical accounts being very contradictory. Some sources claim he had something like a nervous breakdown, or went on a drunken binge; some that he withdrew for a time to force his subordinates to plead for him to take charge, underlining his importance; some that Stalin was his normal tyrannical self. His successors such as Khrushchev had reason to belittle him -- but Stalin also still has his apologists, who continue to claim he did no wrong.

The only thing that can be said for certain was that it wasn't until 3 July 1941 that he addressed the Soviet nation, the delay in doing so being puzzling in itself. He called the people as "brothers and sisters", something he had never done before and would never do again, and asked them to fight a "great patriotic war" against the treacherous fascist invader. He called on them to fight, to take everything away before the advance of the invader and destroy anything that couldn't be removed, leaving nothing but "scorched earth". He defiantly said that the enemy's "best divisions" and air fleets have already been destroyed, though that was an exaggeration.

Stalin delivered the speech in a labored fashion, but it helped kindle feelings of patriotism, and many would remember the address with warmth for the rest of their lives. Whatever Stalin's great faults, the Motherland had been invaded and that was unacceptable -- or at least unacceptable to many. In Ukraine, citizens welcomed the invader as a liberator from Stalin's terrors. Ukrainians jeered at Soviet soldiers as they fled; Ukrainian women blessed German troops with crucifixes as they passed, and Ukrainian men pulled down and smashed statues of Lenin, or piled up images of Soviet leadership and burned them.

In the meantime, the Germans pushed east, towards Kiev, Smolensk, Leningrad. There was panic and chaos, with looting in the cities in the path of the advance. However, although Army Group Center had swallowed up huge Russian armies in front of Kiev, the surrounded Soviets fought on with unceasing stubbornness. German infantry had not moved quickly enough, the huge size of the encirclement spread German resources thin in any case, and many Soviet units had been able to escape. Those that remained were doomed, but they were managing to sap energy and momentum from the German advance, inflicting casualties and delaying the timetable for the offensive.

When the Germans finally stamped out resistance in the trap, they captured 290,000 Soviet prisoners and destroyed or captured 1,500 artillery pieces and 2,500 tanks. However, 250,000 troops managed to escape. Hitler was furious and blamed the panzer group leaders. The panzer group leaders were angry in turn because their tanks were used for mopping-up operations that could have been left to infantry, instead of rapid offensive thrusts.

To the north, the fortress city of Brest held out under incessant hammering by German artillery, with most of the garrison finally surrendering on 29 June after being smashed by Luftwaffe aircraft carrying heavy bombs -- though small pockets held out for several more weeks inside the fortress. One scrawled his testament on the walls: THE GERMANS ARE INSIDE. I HAVE ONE HAND GRENADE LEFT. THEY SHALL NOT GET ME ALIVE. IVANOV.

Even Hitler, who regarded Slavs as subhumans, was impressed, calling the defense a "heroic effort" that demonstrated what should be expected of German soldiers. Hitler visited the fortress with Mussolini as a morale-boosting effort for his troops, to acknowledge their ordeal in the battle.

* The invasion had yielded huge numbers of Soviet prisoners, but they were no particular burden to the Germans, since they were treated with appalling indifference. They were penned into camps that generally consisted of little more than an open field surrounded by barbed wire, with no shelter and little food. Many would die of starvation, disease, and exposure. Many others would, in desperation, put on German uniforms to keep from starving. They were called "Hilfsfreiwillige (Volunteer Helpers)" or "Hiwis" for short, and served as laborers, guards, and in other secondary roles. Ironically, those who put on a Germany Army uniform were always described as "Cossacks" in the paperwork, no matter what their real ethnic derivation was. Hitler loathed the idea of putting Slavic untermensch in the ranks of his fighting forces, but Cossacks were racially acceptable -- and so Cossacks they all were.

Stalin was equally indifferent to the suffering of Soviet prisoners. The Soviet Union had not signed the Geneva Convention, and when the Germans sent feelers through Sweden to discuss treatment of prisoners according to the convention, they were ignored. When Soviet prisoners who had survived were liberated years later, Stalin would not treat them like heroes.

* Stalin was busily returning to his normal form. The first matter to deal with was to find someone to take the blame for the shocking defeat in the west. General Pavlov, commander of the armies on the border, was arrested. He was accused of conspiring with the Germans, even though a week before the invasion he had asked permission to move his troops into defensive positions in the face of clear German preparations for an assault -- a request that was brusquely denied by Stalin.

Under interrogation, Pavlov conducted himself like a soldier, refusing to sign fake confessions, refusing to incriminate others. He was shot. Eight other senior officers were executed as well for "lack of resolve, panic mongering, disgraceful cowardice ... and fleeing in terror in the face of an impudent enemy." There was no acknowledgement of the confused leadership from the top, nor of the fact that the soldiers caught in the onslaught were criminally short of transport, weapons, elementary supplies and equipment, even lacking simple maps.

The cruelty was not completely senseless, however. It didn't take long for tales, with absolute basis in fact, to filter back to Soviet troops that suggested surrendering to the Germans was not a good option. The invaders were quick to shoot Communist officials and Jews, and the treatment others could expect at their hands might make being shot seem swift and merciful. Since Soviet authorities were making it clear that they weren't being much more merciful to those who fell back, the troops had little choice but to die fighting.

Still, it was not just desperation that led Red Army soldiers to often fight stubbornly to the death. Hitler's invasion was only the latest disaster in a land with a history characterized heavily by disasters, and it had bred a certain toughness into the people that was probably their greatest virtue. Even the Germans would come to respect the durability and courage, if not always the skill, of Red Army soldiers.

* Stalin ordered that everything of value be destroyed or removed in front of the German advance. On 24 June GOSPLAN, the state industrial planning organization, began to assemble a massive industrial relocation effort. The effort got rolling with impressive speed, entire factories being picked up and moved to the Urals in a matter of weeks. German long-range reconnaissance aircraft obtained photos of massive concentrations of railroad cars, which puzzled German intelligence; although the Luftwaffe did perform raids against rail centers, they were too feeble to disrupt the movement, the Luftwaffe being heavily committed to the support of the frontline battle.

The German panzers had paused for a week during mopping-up. Guderian chafed at the delay and disobeyed orders, sending his 2nd Panzer Group forward again on 7 July in the reasonable belief that success would grant forgiveness. Kluge went to Guderian's headquarters on 9 July and told him to stop, but Guderian insisted that it was too late to cancel the movement. After much argument, Kluge caved in, telling Guderian: "Your operations always hang by a thread!"

That thread seemed to be fraying. Guderian's tanks ran into rainstorms that turned roads into mud, bogging them down, and Soviet resistance was stiffening. The Soviets had blown bridges and planted mines; since there were few good roads, such measures greatly inconvenienced German armor.

Army Group Center's drive from Minsk towards Smolensk led them to the old defenses of the Stalin Line, from which the Soviets organized a massive armored counterblow. The Soviets were unable to deal with German air superiority, and by 16 July, Guderian's panzers, advancing from the south, were in Smolensk. Guderian had won his gamble.

Unfortunately for Guderian, the Red Army was not completely encircled. The German 3rd Panzer Group to the north under General Hoth was slowed by swampy terrain and substantial Red Army resistance. The Germans were not able to completely close the trap until 26 July. While they captured over 100,000 Soviet soldiers, many more managed to escape.

In fact, the German offensive was becoming increasingly muddled and disorganized. The increasingly protracted campaign of course led to weariness and blunders -- offensives tend to run out of steam as the advance over-extends itself -- but weaknesses in German leadership were also becoming apparent. Although German generals would later conveniently blame Hitler's interference in their plans as the root cause, in fact the situation was much of their own making. The generals argued among themselves, with Guderian proving downright insubordinate on occasion, and sometimes Hitler was forced to intervene just to resolve their disputes. Still, the accomplishments of the campaign so far had left them confident of ultimate victory.

* In the face of these new disasters, Stalin considered making another deal with Hitler, one in which his bargaining position was vastly poorer than it had been in August 1939.

Bulgaria was a German ally, and the Bulgarian ambassador to the USSR, Ivan Staminov, was close to the Soviet hierarchy. Pavel Sudoplatov, a senior NKVD agent and one of Beria's chief lieutenants, even claimed Staminov was a Red agent. According to Sudoplatov, Beria ordered him to contact Staminov in secret and ask him to approach the Germans and ask them if they would stop their war against the USSR if they were handed over the Baltics, the Karelian Peninsula, Ukraine, Belorussia, and so on. Beria warned Sudoplatov that the meeting was to be completely secret: if Sudoplatov said anything about it, he and his family would be executed. The whole story remains murky since it was buried under deep layers of secrecy, but it is said that Staminov was incredulous: "Even if you retreat to the Urals, you'll still win in the end!"

While Stalin considered caving in, he made sure that his own soldiers didn't think of doing the same by issuing Order Number 270 on 16 August 1941. Any officer or political official taken prisoner was effectively a traitor, and would be executed if he ever came back from captivity. Order Number 270 didn't stop there. If any soldiers were taken prisoner or deserted, their relatives were liable to be arrested. If a soldier was blown to shreds or buried under rubble on the battlefield, he might be chalked up as a deserter, with his relatives suffering the consequences.

Stalin's own son, Senior Lieutenant Yakov Dzugashvili, was taken prisoner near Smolensk on 16 July 1941. The Nazis offered to exchange him, but Stalin simply replied that he had no son named Yakov. Stalin sent Yakov's wife Yulia, who was incidentally Jewish and so the target of her father-in-law's antisemitism, off to captivity in Siberia for two years. Ironically, Stalin's own regulations made him liable to arrest as well, but of course he was an exception to the rule.

Yakov would prove defiant and even heroic in his captivity, refusing to stand up if a German officer entered the room and turning his back on Germans who addressed him. He was placed in a punishment cell. After an escape attempt, he was sent off to a secret location. He died in April 1943. A document later obtained by the Americans from German archives stated that he went up to the electrified fence of the compound, as if to climb it, and dared a German guard to shoot him; the guard obligingly did so.

The Germans kept Yakov's death a secret, but Stalin, apparently impressed that his son had not made propaganda broadcasts for the Germans, relented and allowed Yulia to be returned to freedom, such as it was. In 1945, Stalin told Zhukov, giving Yakov a degree of respect that Stalin had never shown his son during the young man's life: "Yakov would prefer any kind of death to betraying the Motherland."

BACK_TO_TOP