* The rise of the Soviet state under Stalin and the threat that state posed to the nations of Europe had helped create Adolf Hitler's Nazi regime in Europe. Although Stalin and Hitler were natural enemies, their mutual fear and loathing led to a startling result: the two dictators decided to become allies. It was strictly an arrangement of convenience, of course. The two knew they would betray each other sooner or later -- and as it turned out, it was Hitler who bettered Stalin at that game.

* In 1936, the Spanish Civil War broke out, with General Franco and his Nationalist forces moving against the leftist Republican regime. The conflict gave Fascism and Communism a worldwide stage on which to trade blows. Hitler found the war convenient, since it distracted world attention from German rearmament; Stalin similarly found the war convenient, since it distracted world attention from his purges. Hitler sent the 8,000-man air-land Condor Legion to augment Mussolini's large-scale aid to Franco. Stalin sent 3,000 Soviet "volunteers", along with fighters and pilots, tanks and crews, to support the Spanish Republicans. Both sides used the conflict partly as an opportunity to test out new weapons and tactics, the Germans evaluating their superior combat aircraft, while the Soviets held an edge in armor.

Franco's Nationalists would crush the Republicans completely in the spring of 1939. Franco was aided by the fact that the Republicans spent an excessive amount of effort fighting among themselves, conducting lunatic purges that dissipated energy and spread demoralization. Stalin sent agents of the NKVD, the new name for the OGPU, along with the fighters and tanks, and the NKVD men hunted down Trotskyites and anarchists ruthlessly. Stalin proved more interested in crushing his internal enemies than in winning the war.

However, although the Republicans lost the civil war, the conflict proved a significant propaganda victory for Stalin. The Soviets seemed to Westerners to be making a valiant stand against Hitler and Fascism, while Stalin kept his own brutalities hidden. Many Westerners became Communists, and some, like Kim Philby in Britain, were recruited by the NKVD to become spies. When the war was over, the Soviet military advisers and NKVD men returned to the USSR. They had been contaminated by contact with the West, however, and had been out of sight and so out of control; to Stalin, they were suspect, and many of the senior officers among their ranks were executed.

* While Stalin was primarily focused on Hitler and events in Europe, he also had the Soviet Union's "back door" in the Siberian Far East to worry about. The Japanese were clearly an enemy, and just as clearly would exploit Soviet weakness in Siberia if the opportunity arose. The Soviets had been providing arms to Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist Chinese government to make trouble for the Japanese -- for whatever reasons, Stalin preferred to back the Nationalists instead of Mao Tse-tung's Chinese Communists. The war materiel provided by the USSR was modest, war on the cheap, supplies of light weapons such as firearms and grenades.

The Japanese were sufficiently irritated by Chinese harassment to begin a war against Chiang's Nationalists in 1937. The Nationalists were no match for the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), but the Japanese didn't have the manpower to hold down Chinese territory and, though they won victory after victory, simply became more bogged down. That was all to the good from Stalin's point of view, since as long as the Japanese remained mired in China, they weren't in a good position to make trouble for the USSR.

However, the IJA's officer corps had been raised on a doctrine in which superior Japanese determination would overcome all obstacles, leading to an ingrained habit of underestimating enemies and the difficulties of offensive operations. The IJA's leadership was firmly anti-Communist, seeing the Soviet Union as their traditional enemy and the vast expanses of Siberia as a natural target for Japanese expansion. Border incidents had taken place from the start of the conquest of Manchuria and had steadily ramped up. In June 1937 the Japanese had sunk a Russian gunboat and damaged another on the Amur River, which defined the border between Siberia and Manchukuo, when the Soviets had attempted to occupy a contested island in the river.

The Soviets seemed so intimidated by the action that IJA generals thought the Red Army would be easy to push around. It wasn't; the Soviets had simply not been prepared for a fight at that time. They quickly got ready for one, continuing to build up forces. By the summer of 1938, there were an estimated 24 Red Army divisions supported by 2,000 aircraft in the Soviet Far East. At the end of July 1938, after a bout of rising border frictions, Japanese troops overran Soviet border posts that had been recently set up near Lake Khasan about 100 kilometers (62 miles) down the coast from Vladivostok, where the USSR had a major naval base.

The Red Army threw at least three divisions back at the Japanese and the fighting bogged down, with a cease-fire implemented on 11 August 1938. For the moment, all was quiet in the Far East -- but the Red Army had suffered worse in the clash than the IJA, and the Japanese were looking forward to a rematch.

BACK_TO_TOP* Stalin kept the Soviet propaganda machine in full gear to denounce Hitler and the Nazi regime, though events would soon prove there was less to it than met the ear. At the League of Nations, Soviet Foreign Minister Maxim Litvinov appealed to western nations to help confront Germany, and in London, Soviet ambassador Myske was sounding out the British and French. The diplomatic measures were not resoundingly successful. Stalin did not trust the West and he was not trusted in return, particularly since the "Comintern" (the Communist International movement) was busily engaged in subversive "agitprop (agitation-propaganda)" against Western governments, with particular effect in France.

In March 1938, Hitler annexed Austria unopposed. Once again, Britain and France failed to respond to a gross provocation. Now Hitler turned his attention to Czechoslovakia, angrily denouncing the "persecution" of ethnic Germans in the Czech border region of the Sudetenland and mouthing threats at Prague. By the end of the year, the British and French, through the mediation of Mussolini, pressured Czechoslovakia into ceding the Sudetenland to Germany. Since the Sudetenland contained the only practical defenses against a German invasion, Czechoslovakia was now wide open to invasion.

British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, returning from the signing of the Munich Pact that ceded the Sudetenland to Germany, announced in a phrase that has become a historical exercise in irony: "Peace for our time." Winston Churchill said: "The governments of France and Britain had to choose between shame and war. They have chosen shame." In early 1939, Hitler occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia and declared that the country no longer existed.

Given how devious Stalin was, it is unclear that he was ever really sincere about courting the West. His diplomatic overtures may have been nothing more than a way of raising the stakes in a potential deal with Hitler. If so, now it was time to make such a deal. Despite the noisy and acid accusations flying back and forth between the two countries there was no real obstacle to coming to a convenient agreement -- neither dictator being burdened by any sense of principle.

The prize in the deal was Poland. Hitler wanted to expand East, and Poland was clearly the first target. As long as Hitler was devouring Poland, Stalin saw no reason why he should not get a piece as well, since it was valuable property in itself and would serve to provide further buffer space between Moscow and Berlin.

* In March 1939, the 18th Party Congress met in Moscow. Applause for Stalin was loud, continuous, and strained, since everyone knew any sign of a lack of enthusiasm might be fatal. Indeed, it is said that there were NKVD agents among the crowd looking for anyone who seemed insufficiently motivated. 60% of the delegates from the previous Party Congress were dead by this time. That was the visible tip of the iceberg. In the 1937:1938 timeframe, there had been from 7 to 8 million arrests and at least a million executions. At a site near Minsk, one mass grave held 30,000 bodies.

On the fifth day of the Congress, the news reached the body that Hitler had occupied Czechoslovakia. War was clearly imminent. Although Stalin had little faith in France and Britain, he still allowed Litvinov to make one last appeal for collective security against Germany. The appeal went nowhere; the French and British were clearly not going to do anything. On May Day, the USSR conducted its annual military parades. Observers had long realized that the lineup of figures on the podium with Stalin was a significant hint for who was important and who was not in the leadership circles. German diplomats realized that Litvinov, the advocate of collective security with France and Britain, was not there.

The next day, Hitler was told that Litvinov has been replaced by Vyacheslav Molotov as foreign minister -- Litvinov, incidentally, was not purged, just put on the shelf in case he might prove useful later. To the Fuehrer, the news was like "a volley from a gun". In July, Molotov told the German ambassador to the USSR that the Soviet Union sought better relations with Germany. Diplomatic contacts and negotiations intensified, even as the propaganda machines of both nations continued to pour out mutual abuse. On 11 August, an Anglo-French military mission arrived in Moscow to discuss military cooperation. The effort was half-hearted, and they were wasting their time anyway.

Hitler had worries about invading Poland as long as there was a strong possibility that the Soviet Union might intervene against him. The diplomatic feelers seemed to be moving too slowly, so on 20 August Hitler personally wired Moscow, suggesting that the Nazi foreign minister, Ribbentrop, go there in two days. On 23 August, Ribbentrop flew to Moscow. His trip did not exactly go smoothly; the haste in which the meeting had been arranged led to a bureaucratic mixup, and his airliner had been fired on by Soviet border defenses and forced to land. The snarl was cleaned up and matters moved on.

The Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact was drawn up quickly and signed. Stalin drank a toast to Hitler -- though when Ribbentrop drafted a bright and enthusiastic press release, Stalin suggested that it be toned down a bit in light of the fact that the two nations had been "pouring filth over each other" for years. The pact had secret clauses, one of which acknowledged the right of USSR to occupy the Baltic States, with the Soviet Union paying Germany a large sum in compensation for Hitler's claims in Lithuania. Another secret clause detailed the partition of Poland. Soviet Anti-Fascist propaganda was ordered stopped immediately. In fact, the term "Fascist" was banned from public media, and would not resurface again officially for the better part of two years.

On seeing a news report of the pact, cadets at a Soviet military staff college thought it was some sort of prank. Those who believed it were shocked. Some Communists in other nations finally saw Stalin for what he was, a cynical tyrant, though most Reds went into denial and simply toed the party line, even when it meant they had to perform handflips to do it. Intelligent observers knew the pact meant war.

BACK_TO_TOP* In the interim, the fighting between the Soviets and the IJA had flared up again. Some sources claim the Japanese wanted to derail Nazi-Soviet rapprochement, but the clash was more or less spontaneous, inevitable given the presence of hostile forces and a border dispute. There was a difference of opinion over the positioning of a part of the border between Manchukuo and the Communist People's Republic of Mongolia, which was independent of the USSR but effectively a Soviet satellite. The Japanese maintained the border was along the Khalkhin Gol (River), while the Mongolians and the Soviets countered that it was about 16 kilometers (10 miles) to the east, near the village of Nomonhan.

In mid-May 1939, frictions started to build up when a small Mongolian cavalry unit entered the disputed border region to obtain grazing for their horses. One thing led to another, and the Japanese Kwantung Army sent in a regiment to clear out the Mongolians. The Mongolians and the Soviets came back promptly and, on 28 May, effectively wiped out the Japanese regiment.

Both sides began a military buildup in the area, leading to a series of small battles at the end of June. Although the Japanese government in Tokyo tried to restrain the Kwantung Army, in early July the IJA 23rd Infantry Division conducted a full-scale offensive into the disputed region to "drive the invaders out". After bitter fighting through most of July, Red Army forces under General Georgiy Zhukov stopped the Kwantung Army offensive cold in a bloody battle.

The two sides planned to renew the offensive to break the stalemate, but Zhukov was able to obtain heavy reinforcements and struck first, on 20 August. Soviet and Mongolian troops performed a classic "double envelopment" against the Japanese, the two arms of the offensive meeting up at Nomonhan to trap the 23rd Infantry Division. The Japanese managed to break out of the trap, but only with severe losses. Both sides had suffered heavy casualties in the little war, but the Soviets could spare them more easily, and the Battle of Khalkhin Gol, as the Soviets called it, or the Nomonhan Incident, as the Japanese referred to it, had been a clear Soviet success. It would prove a template for Zhukov's later operations -- both in its overall strategy and in its general indifference to the lives of Soviet soldiers, though the IJA suffered much worse.

Kwantung Army leadership wanted to perform a counteroffensive, but the Japanese signed a cease-fire with the Soviets, and Tokyo finally managed to get the fighting to stop. The border conflict had been upstaged by events in Europe and so attracted little attention worldwide, but the action was significant. To Stalin, it was a propaganda victory that avenged Russia's humiliation in the 1905 Russo-Japanese war, and it did much to enhance Soviet security in the Far East.

Although IJA leadership tried to sweep the defeat under the rug, dismissing it as an anomaly, the Japanese were still not inclined to get into a fight with the Red Army any time soon, leading to a drift towards a diplomatic rapprochement between the USSR and Japan -- with Soviet assistance to Chiang's Nationalists drying up as a consequence. The signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact had also not gone over well in Tokyo, leading to a cooling of relations between Japan and Nazi Germany, though the chill would only prove temporary. The bottom line was that Stalin's worries about the Japanese were on the back burner for the time being.

There was another consequence of the border war, in that to the extent the rest of the world took notice of it, the Japanese were misleadingly seen to be militarily weak and inept. This perception was underlined by a subsequent failure of Soviet arms that made the Red Army look weak and inept as well.

BACK_TO_TOP* The British, though unprepared, had swallowed enough of Hitler's assurances. Within two days, Chamberlain signed a treaty binding Britain to go to war if Poland were invaded. On 31 August 1939, Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels claimed that Poland had attacked German towns near the Polish border. A raid was staged with SS men in Polish uniforms, and a concentration-camp prisoner killed as a prop. The Germans invaded Poland the next day. On 3 September, the British kept their commitment to the Poles and declared war on Germany. The French joined the British within hours.

The Wehrmacht swept through Poland. The Polish Army fought back as well as it could, but the Poles were overwhelmed. Luftwaffe bombers pounded Warsaw. Soon Stalin made his move, invading Poland from the east on 17 September 1939, two weeks after the beginning of the German invasion. German and Soviet generals conferred to coordinate their actions, and Luftwaffe aircraft were allowed to use Soviet air bases near Minsk in their operations against the Poles.

The Red Army's advance into Poland did not match the efficiency of the German invasion, Soviet movements being hobbled by Polish resistance and by logistical failures. However, within six weeks, Poland had ceased to exist. German and Soviet troops performed a collaborative military parade for their military leaders near the fortress of Brest. The NKVD moved in behind Soviet soldiers, and arrests, deportations, and executions began. Roughly 15,000 Polish officers were trucked off to Katyn Forest near Smolensk, and were not seen alive again. Polish farmers were forced into collectives, while young Polish men were conscripted into the Red Army. They would not prove enthusiastic soldiers.

* Hitler's rapid conquest of Poland enhanced Stalin's fears of the German Reich, Soviet observers having estimated that it would take much longer than it did. However, Koba was pleased to see the Western powers at each other's throats. He believed they would weaken themselves fighting each other, and in the meantime they would not be in a position to interfere with Soviet aggressions. Encouraged by success against the Japanese, Stalin overreached himself. He had attempted to negotiate with the Finns to obtain strategically important Finnish territory that would help defend Leningrad. The Finns were open to the idea of adjusting their borders somewhat, trading Soviet territory for Finnish territory, but Stalin also wanted to establish a naval base at Hango, well to the west; the Finns didn't like that idea. After two months of negotiations that went nowhere, on 30 November 1939 Stalin invaded Finland with 29 divisions. The Finns faced the invasion with only nine divisions.

Red Air Force bombers kicked off the attack with raids on Helsinki and other cities, while the Soviet divisions -- organized into five armies -- drove into the country all along the frontier. Stalin was confident that Finland would be conquered in two weeks or so, with Red Army troops given instructions on how they should conduct themselves when they reached the Swedish border. However, the Finns were prepared for the attack. They had built stout defensive lines, and in the northern parts of the country roads and other facilities along the border had been left undeveloped to channel attacks into kill traps. Soviet intelligence was so poor that the invaders simply blundered into them, to be slaughtered.

Stalin had expected the Finns to sue for peace immediately. Instead, they loudly protested the bombings of their cities in the world press, with Soviet propaganda foolishly claiming that all the bombers had dropped were breadbaskets. The Finns provided pictures of bomb damage -- including hits on the Soviet embassy -- and began to refer to Soviet bombs as "Molotov breadbaskets". Finnish leader Augustus von Mannerheim was strong-willed and competent, directing a stubborn defense; two Soviet armies driving up the Karelian Isthmus were stopped cold at the system of fortifications known as the "Mannerheim Line". Three other Soviet armies driving into Finland in the center of the borderline were hit with flanking counterattacks and badly chewed up. One of these three armies, the Soviet 9th Army, was cut off and completely destroyed.

Soviet troops advancing through the frontier forests found them wintry deathtraps, one soldier saying: "There was no enemy visible anywhere. It was as if the forest was doing the shooting all by itself." The Finns would disappear into woods if the Soviets tried to chase after them in force. If the force was too small, it was likely to be ambushed and completely wiped out. One Ukrainian private wrote: "They are swatting us like flies."

In the north, the Soviets did achieve success by seizing the Arctic port of Petsamo, which was in an important nickel-producing area. However, the great Soviet giant had been humiliated. The Red Army purges had done much to wreck the Red Army, and now the weakness of the Soviet giant was in full view for all the world to see. Unsurprisingly, Stalin's reaction was to seek scapegoats, with a number of officers executed, which simply added to the Red Army's difficulties.

The Winter War lasted four months, through one of the harshest winters in memory in a region where winters were normally harsh. The Red Army finally sat down, got organized, and set up a proper offensive using eleven more divisions and large quantities of tanks and aircraft. The offensive jumped off on 28 February 1941 and ground its way through Finnish defenses. The Finns were forced to capitulate, with an armistice going into effect on 9 March. Finland had to cede important territories to the USSR.

The victory was a bitter one for Stalin. Over a million of his soldiers had been committed to battle, and at least 200,000 of them had been killed. One Soviet general was said to have remarked: "We have won enough ground to bury our dead." Stalin was indifferent to the suffering of his people, but he could not conceal that the Red Army was weak and inept. He began an immediate program to repair the damage he had done to the military. There was a major reorganization in early May 1940, with some competent officers placed in top positions. Zhukov, who had been brought west late in the Winter War thanks to his performance at Khalkin Gol, became chief of staff of the Red Army.

However, Stalin still wanted the military under his thumb. Inept toadies were retained in high positions, and signs of independence by others were not tolerated. When a senior Red Air Force general named Rychagov was criticized in a meeting with Stalin and others for excessive numbers of crashes, he replied angrily that he was being given "flying coffins" and not airplanes. Stalin replied coldly: "You should not have said that." Rychagov was promptly arrested, and later shot.

Hitler did not fail to take the Winter War into account, seeing in it more evidence of Stalin's untrustworthiness, as well as evidence that the Red Army was a paper tiger. The friendship of two thieves still continued in public. In December, Stalin turned 60 years old, and Hitler sent him cordial greetings; Stalin proclaimed in return their "long-lasting" friendship. The Soviets sold the Germans grain, oil, and other raw materials, in accordance with trade agreements that followed on the coattails of the non-aggression pact, and Stalin even arrested German Communists who had fled to Moscow. They were handed over to Hitler's Gestapo, to be tortured and executed. Stalin went so far as to allow the Germans to set up a U-boat base near Murmansk, though it never became operational since the British sank the first two submarines sent there, and events soon rendered it irrelevant anyway.

* In the West, a "Phoney War" prevailed, with France and Britain in a largely defensive posture. There was little action, and little pressure was put on the Germans. The quiet did not last.

On 8 April 1940, Hitler invaded Denmark and Norway. Denmark was swiftly occupied. An Anglo-French expeditionary force attempted to defend Norway and inflicted substantial naval losses on the Germans, but the Germans managed to drive the British and French out, with the Norwegians forming a government in exile. Norway's fjords provided excellent naval bases for the German Navy's ships and submarines.

The failure of Allied forces to prevent the fall of Norway humiliated the Chamberlain government. Chamberlain resigned, with Winston Churchill becoming Prime Minister. He was immediately confronted with a crisis. On 10 May 1940, Hitler invaded the Low Countries and France. Three German Army groups participated in the offensive, with the main weight of German armor provided to Army Group A, operating through southern Belgium and Luxembourg.

The Germans were faced by the Belgian and Dutch armies, three French army groups, and a mobile British Expeditionary Force (BEF). German Army Group B swept into the Netherlands and northern Belgium, quickly rolling back resistance, and drawing a French army group and the BEF north along the coast to meet them. It was an enormous trap. German Army Group A swept through the center of the French lines and swung northwest towards the coast. By 27 May, Anglo-French forces along the coast were encircled. By 5 June, the pocket was all but eliminated. However, most of the BEF and many French troops were evacuated across the English Channel from Dunkirk. 330,000 men escaped, though they lost most of their heavy equipment.

Churchill tried to rally resistance against the German offensive through France, but Hitler's Wehrmacht was unstoppable. The German divisions turned south. Army Group B reached the Seine below Paris on 9 June. Army Group A broke through French lines to the northeast of Paris on 12 June and charged into the interior of the country, while Army Group C, facing the French Maginot Line, jumped in and help complete a massive encirclement of French forces. Surviving French forces were in wild flight, and on 17 June the French government capitulated. On 22 June, Hitler accepted their formal surrender. Hitler returned from accepting the French surrender to Berlin, where he was given a hero's welcome. He had conquered France, succeeding when the Kaiser had failed.

Stalin closed down Soviet embassies as the nations of the West fell to the German juggernaut, in recognition that these nations no longer had an independent existence. However, Koba was startled by the rapid collapse of France: "Couldn't they have put up any resistance at all? Now Hitler's going to beat our brains in!" Stalin still had to keep up appearances and sent congratulations to the Fuehrer on his "splendid success".

The German preoccupation in the West still presented an opportunity, and of course Koba made use of it. In June 1940, Stalin swallowed up the Baltic States, within a few months annexing Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, including the small German territorial concession in Lithuania. The NKVD moved in, and instituted the terror in which NKVD agents had become so practiced.

At the end of June, Stalin also demanded that Rumania cede important border regions to the USSR, with these regions quickly occupied by the Red Army. Rumania was a German ally and the Reich's main source of oil. The Rumanian territories occupied by the Soviets gave Stalin a position from which he could grab Rumanian oilfields. Hitler, recognizing the threat, moved more forces into Poland to counter Soviet moves; he also signed treaties with Finland, Hungary, Rumania, and Bulgaria to allow the movement of German forces through their territories. Stalin, alarmed, offered concessions to Berlin.

Stalin also took care of smaller items. He had a score to settle with Leon Trotsky, his old rival, who had sought asylum in Mexico and was publishing annoying blasts against Stalin in the Leftist press, with titles like "Stalin, Hitler's Quartermaster" and "The Heavenly Twins, Hitler & Stalin". Trotsky knew that Stalin had a long reach, but though Trotsky was at heart just as ruthless as Stalin, he was courageous and did not try to hide. A Red agent named Ramon Mercador infiltrated Trotsky's household and, on 20 August 1940, smashed in his skull with a mountain-climbing pick. Many sources give the weapon as an "ice pick" which is sort of true but misleading; the mountain-climbing pick was a favorite weapon of NKVD agents, since it was easy to carry and conceal, and was highly lethal.

Koba's orders were implemented by Lavrenti Beria, who had become head of the NKVD in 1938 following the arrest and execution of his predecessor. He had become one of the most indispensable of Stalin's cronies; pictures show a balding man, appearing sinister behind round glasses and usually wearing a slight, contemptuous smile. He was a toady, and it was said that his hobby was rape: his men would pick up an attractive girl and take her to his quarters, where he would give her a glass of drugged wine that would render her agreeable. Afterwards, she would be thrown back out on the streets. Who could she complain to? The law? Beria was the law, or what passed for it.

BACK_TO_TOP* Winston Churchill was determined to carry on the fight with the Nazis. Even before the fall of France, Churchill had decided to restore diplomatic relations with the USSR -- the British ambassador to the Soviet Union had been withdrawn in protest during the Winter War -- and dispatched Sir Stafford Cripps, a prominent British Socialist, to Moscow, with the diplomat arriving at the beginning of July. Cripps carried a letter from Churchill outlining Nazi plans against the Soviets.

Stalin regarded the letter as pure lies, and even went so far as to tell the Germans what Churchill was up to, as a way of reassuring the Reich that the USSR really was a reliable ally. Cripps remained in Moscow, but Koba merely toyed with the ambassador, using him mostly to "annoy the Germans". Stalin certainly had no trust in Adolf Hitler, but everything seemed to be working well for the Red cause. Koba was perfectly happy to see the Western nations wear themselves out, while he took advantage of the situation to seize more territory for himself.

As for Germany, Stalin believed he could deal with that problem later. German bombers were pounding Britain in an attempt to pave the way for invasion; Stalin did not think that Hitler would attack the USSR while the British were still actively fighting the Reich, that the Fuehrer would not be so mad as to commit Germany to a war on two fronts. Stalin believed that there was no way that Hitler would be able to turn on the Soviet Union before the spring of 1942. Besides, Hitler usually conducted a propaganda offensive against a victim before invading it, which would give Stalin warning that an attack was coming.

In reality, Hitler had decided to deal with the USSR on his return from accepting the surrender of the French. Although he had spoken against conducting a war on two fronts in MEIN KAMPF, the French had been taken completely off the playing board, and he believed that Britain had been more or less militarily neutralized; they might even come to terms with the Reich soon enough. That belief that was subtly encouraged by Churchill, who sent bogus "leaks" to the Reich through indirect and completely deniable channels suggesting that a deal might be possible. Publicly, Churchill made it very clear that a deal was out of the question -- and he meant it.

An attack on the Soviet Union was still risky, but Hitler believed he had good reason to move quickly. He judged that the British were fighting on in expectation that the Soviets would join in on their side -- a notion that was given some substance in the Fuehrer's mind by visits of British ambassador Cripps to the Kremlin. Stalin simply wanted to use British diplomatic overtures as a lever against the Germans, a hint that the Soviets might lean toward the British if the Reich didn't play nice; but to Hitler's suspicious mind, the hint sounded much more like a dire threat. The Fuehrer saw the diplomatic exercise evidence of an emerging conspiracy of Britain and the Soviet Union against Germany. However frustrating it was to Cripps to put up with Stalin's games and snubs, the ambassador's presence in Moscow was still serving, in a Zen fashion, Britain's interests.

Very well, so Hitler thought, crush the USSR and the British would have nowhere to turn to, the Americans having up to that time not shown the least interest in going to war with the Reich -- though the fall of France had been a wake-up call to the USA, the country beginning to mobilize for war in earnest. The Soviet Union was rearming and the Red Army was being reorganized, it made sense to strike before the Soviets became a greater threat; wait another year and the prospects of success against the USSR would be much poorer. Besides, if there was going to be a long war, the Reich needed to get control over Soviet resources to sustain the fight.

Hitler had logical reasons to invade the USSR as soon as possible, and no good reason to show his hand with belligerent propaganda. After a few days of consultation with key advisers, on 31 July 1940 he announced to his generals his intent to attack the Soviet Union within a year. Hitler's generals later claimed they were unhappy with the idea, but this appears to have been self-serving hindsight. The dismal performance of the Red Army against Finland seemed to prove that the USSR was no match for Germany. Hitler told his generals: "You only have to kick in the door, and the whole rotten structure will come crashing down."

Hitler signed "Order 18", formally stepping up preparations for the invasion of the USSR. He continued to build up a fleet of landing craft to invade Britain through the summer, though his military planners couldn't agree on how it might be successfully done. By the end of the summer, mounting losses of aircraft over Britain would force the Luftwaffe to turn to inaccurate night attacks, intended to terrorize the British people and hopefully get rid of the pigheaded Churchill -- though it simply ended up drawing out deep reserves of stubbornness and defiance.

Bombers of the British Royal Air Force (RAF) had proven effective in smashing concentrations of German shipping and landing craft in French ports, forcing Hitler to disperse the shipping. The plan to invade Britain, such as it was, was shelved indefinitely. Hitler was already talking to the Japanese to seek assistance in an attack on the Soviet Union. The Japanese, however, had nothing to gain from a fight with the USSR, and would sign a non-aggression treaty with Stalin in April 1941.

* In the meantime, the false front of the thieves' friendship was beginning to wear thin. In November 1940, Molotov went to Berlin at Hitler's request. Hitler proposed that the USSR join the Axis, claiming that Britain was all but beaten and that the Soviet Union should work with the Germans to help carve up the British Empire. Molotov -- notoriously single-minded and impassive, being nicknamed "Stone Ass" for his immobility in negotiations -- simply replied with a list of complaints about unfriendly German actions in Finland and Rumania. The two sides were not communicating, which was just as well for the Soviets since Hitler was clearly engaging in a deception operation. On the last night of the conference, 12 November 1940, British bombers raided Berlin. Molotov asked Ribbentrop: "If England is beaten, why are we sitting in this shelter?"

Molotov went back to Moscow empty-handed. Stalin still did not anticipate war, though he was becoming more nervous. The Soviet Union had no allies, while its military remained in a disorganized and demoralized state. In truth, Stalin had committed himself so thoroughly to the friendship of convenience with Hitler that he failed to understand just how great the danger to the USSR really was. He was the Great Leader. He was infallible. No one dared defy him. He could not be wrong.

In early May, Stalin appointed himself premier, retaining his position as party secretary, to underline his absolute grasp on power. It was nothing much more than a formality, even a vanity; he could have every title or no title at all, there was no challenging his commands under any circumstances.

BACK_TO_TOP* Hitler knew that a long campaign against the USSR would be dangerous. He told his generals that the Red Army had to be decisively defeated in no more than ten weeks, and that the whole campaign could not last more than 17 weeks. Hitler was concerned about having to fight during the notoriously difficult Russian winters, and he also knew that the Reich didn't have the logistical capability to support a long war.

The German attack plan, codenamed Operation OTTO, was constrained by Russian terrain, particularly the huge region of swamps, bogs, and forests known as the Pripet Marshes that stood in the center of the path of an advance into the Soviet Union. The Pripet Marshes were 480 kilometers (300 miles) wide and 240 kilometers (150 miles) deep. An attack would have to flow around the north of the marshes toward Minsk and around the south of the marshes toward Kiev.

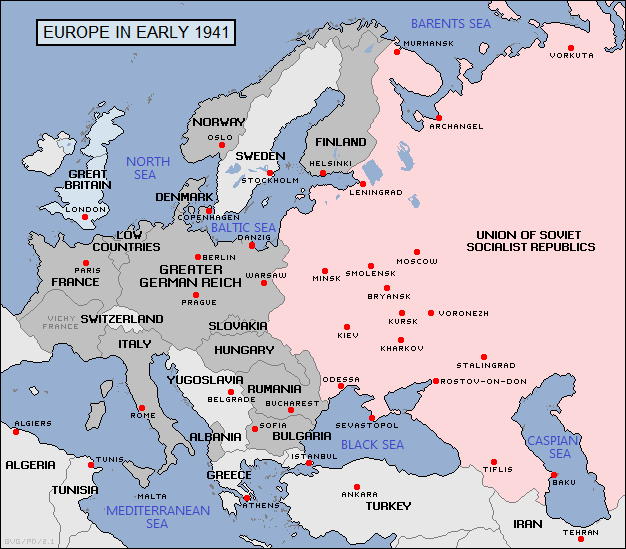

The planners of the operation assumed that the Soviets would establish major forces north and south of the marshes, with a reserve in the rear near Moscow. Three army groups were to mass on the border of the USSR, with Army Group North assigned to drive from East Prussia north towards Leningrad, which had extensive armaments industries; Army Group Center assigned to drive from East Prussia and Poland through Minsk and Smolensk and on towards Moscow; and Army Group South assigned to drive from southern Poland and Rumania towards Kiev, the heart of Ukraine.

Once Leningrad and Kiev on the flanks were secure, Army Groups North and South would converge on Moscow to help Army Group Center crush the Red Army for good. The generals spent four months working on the plan for OTTO, which evolved to a modified plan named FRITZ, and tested their plans with large-scale military exercises, but Hitler did not like it. Hitler thought seizing Moscow was irrelevant. The real objective was to destroy the Red Army. Hitler did not want to end up like Napoleon, isolated in Moscow while the Russians cut his supply lines. In December 1940, he canceled FRITZ and put a new plan in its place. The new plan was codenamed Operation BARBAROSSA, meaning "Red Beard", for the German 12th-century emperor Frederick I, who had died on a crusade. According to legend, Barbarossa would rise again when the German people needed him the most.

Hitler insisted that the Red Army must be destroyed in the western regions of the Soviet Union, in front of a line defined by the Dvina and Dnieper rivers. Army Group North would drive towards Leningrad as before, but its primary objective would be to drive Soviet forces into the Baltic States, where they would be encircled and destroyed.

Army Group Center would drive beyond Minsk and towards Smolensk in a two-pronged attack designed to encircle Soviet forces in the region, and then destroy them. Army Group Center would then move from Smolensk to help Army Group North in the drive on Leningrad. Capture of Leningrad would give the Germans a valuable port to help support further offensive operations. Although a number of senior officers disagreed, Hitler did not believe that Moscow was all that important. Its capture could wait.

Army Group South would move on Kiev as in OTTO and then curve south along the Dnieper to isolate Soviet forces in the region and then wipe them out. With Soviet forces in Ukraine eliminated, Army Group South would then move on to the industrial regions of the Donetz Basin and the oilfields of the Caucasus.

Once these operations were complete and most of the Red Army was destroyed, then all three army groups would converge on Moscow to finish the offensive. The Germans would consolidate their new territory, establishing a defensive border line anchored at Archangel in the north running south along the river Volga. There was no thought of advancing farther; an advance to the Pacific through what was mostly wilderness would have been a logistical monstrosity, and Hitler knew he didn't have the resources to try, or for that matter much reason to care. With the Red Army destroyed and the most valuable assets of what was once the USSR in German hands, Hitler's new eastern empire would be secure. The industrial regions of the Volga Basin and the Urals would be smashed by the Luftwaffe, ensuring that what remained of the Soviet Union would not be able to regain strength. No doubt the Bolsheviks would come to terms, however humiliating they found them.

The German Army's panzer divisions were to spearhead BARBAROSSA. However, the senior commanders of these forces did not like the plan. General Heinz Guderian, who had developed armored blitzkrieg tactics and demonstrated their effectiveness in the conquest of France, pleaded with Hitler for a bolder stroke that would take advantage of the army's mobile formations. Guderian wanted the armored divisions to plunge as deeply as possible into the USSR, even if they had to be supplied by parachute drops. The deep thrusts would complete disrupt Soviet defense plans, and the infantry divisions following the armored spearhead could mop up the disorganized Red Army.

Hitler rejected Guderian's proposal. The armored divisions would operate as components of the rest of the offensive. In fact, they would mostly be under the senior command of infantry generals who had more conservative ideas about tank warfare. Guderian's disgust was greatly aggravated by the fact that he had grave doubts that an attack on the USSR was wise, and few doubts that it would be very difficult.

The conquered territories would be completely subservient to the Reich. Some ethnic groups, such as the Balts, were regarded as sufficiently Aryan would be "Germanized" and made obedient subjects. Slavs would be enslaved, or simply allowed to starve to death to free their lands for settlement by Aryans. Jews and other undesirables would of course be eliminated.

Late in the planning Hitler issued two orders, one that stated that all Soviet political commissars captured were to be promptly executed, and another that German soldiers who mistreated or killed Soviet civilians were not to be disciplined. Both orders were brutal, and the order giving German soldiers a license to do whatever they liked to the populace was contrary to every concept of conduct and discipline the German officer corps had ever believed in. Some officers refused to accept the order. One wrote in his diary after seeing it: "This kind of thing turns the German into a type of being which had existed only in enemy propaganda." He was a minority; some German Army officers were actually enthusiastic about the harsh measures.

* The Commander of the German Army (Oberkommando des Heeres / OKH) in 1938 was Werner von Brauchitsch, a competent but not brilliant general, chosen more for his loyalty to Hitler than for his abilities. Brauchitsch had operational control of the Army during the blitzkriegs against Poland and the West, but he had little say in the overall planning of the war. When he opposed Hitler on logistical planning for the attack in the west, the Fuehrer browbeat him at length, and would not allow him to resign.

Many senior German officers didn't need to be told to toe the line. The OKH chief of staff, Colonel General Franz Halder, was optimistic as well. He agreed that the war would only last ten weeks at most, and there was no strong effort to arrange the production of winter clothing for a longer campaign. They were suffering from "victory fever", a belief in their own invincibility as proven by the easy campaigns in the West. Guderian wrote in his memoirs that senior Wehrmacht officers had eliminated the word "impossible" from their vocabulary -- though it has to be noted that his memoirs were written after the fact, and no doubt colored appropriately.

BACK_TO_TOP