* Creationism, in the 21st century, appears to have run out of steam, neither having had any real success, nor able to conjure any new arguments. Creationism can only forever recycle the argument made by the Reverend Paley over two centuries before -- an argument that was weak when it was new, and hasn't improved with age.

* William Dembski was never the least impressed by the criticisms leveled at the Law of Conservation of Information, replying with a combination of evasion, obfuscation, and derision. To back up his case, he resorted to probability calculations, not so different from those advanced by the Reverend William A. Williams, as well as willfully obscure mathematical notation. It was a non-starter. All squabbling over technicalities aside, the argument suffered from an unavoidable weakness: it was entirely theoretical.

A theoretical argument about the real world can be devised to prove anything -- but it can be no more realistic than the assumptions on which it is based, and can only be shown to be valid by its conformance to observations. Dembski could prove anything he liked in theory; without validation, any theory he proposed would be just as good as any other. He refused to even consider the question of how the Law of Conservation of Information could be validated, responding to demands for validation with:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

I'm not going to take the bait. You're asking me to play a game: "Provide as much detail in terms of possible causal mechanisms for your ID position as I do for my Darwinian position." ID is not a mechanistic theory, and it's not ID's task to match your pathetic level of detail in telling mechanistic stories. If ID is correct and an intelligence is responsible and indispensable for certain structures, then it makes no sense to try to ape your method of connecting the dots.

END_QUOTE

Dembski was unusual among creationists in that, when confronted by an obvious problem with his thinking, he would acknowledge it, and claim it was a virtue: That's not a bug, that's a feature. One response, which summed up the attitude of his critics, was: "You're already playing a game. We're asking you to stop."

Any attempt to validate the Law of Conservation of Information was doomed to failure. As we continue to unravel the genomes of more and more organisms, we are able to see patterns in those genomes of past evolution, being able to identify gene changes that split one branch of organisms off from another, down to ever finer levels of detail.

We are, in short, acquiring a map of the genetic changes that produced the organisms that exist today. The genetic changes in the map can be accounted for by known processes of genetic variation, and in fact in many examples -- such as duplications of sets of chromosomes in plants -- the processes are obvious. We will not only be able to show that evolution could have gone from here to there, but show the steps by which it did. Where there is uncertainty, we could postulate as many sequences as possible and feel confident one of them is probably right. That would leave creationists in the impossible position of backing up the assertion that such mutations had been the work of an Unseen Agent. Creationists, of course, make impossible arguments all the time.

* While the scientific research generated by the Discovery Institute amounted to nothing, science wasn't what the organization was honestly about. Its main focus was to lobby to teach creationism, camouflaged under the guise of ID, in the public schools, insisting that schools needed to "teach the controversy". The response, of course, was that any controversy over the science was completely manufactured; there was no significant controversy within the science itself to be taught.

The first major political issue involving Discovery Institute staff took place in 2001, when Pennsylvania Senator Rick Santorum attached language, partly written by Johnson, to encourage "teaching the controversy" to a child education bill. This effort was a fizzle -- the language was cut in committee, and didn't make it through to the final bill. The next year, 2002, a bill to "teach the controversy" was brought before the Ohio state legislature, but despite personal lobbying by Johnson and Dembski, the bill didn't pass.

However, the Discovery Institute was also pursuing a tactic of lobbying state education boards directly. Such boards set state educational agendas, and lobbying the boards attracted much less attention than lobbying state legislatures. Some members of the Ohio state education board were sympathetic to the lobbying, and decided to include "teach the controversy" in the educational curriculum. Matters came to a head in an attempt in 2004 by the school board of Dover -- a rural town in the state of Pennsylvania near Harrisburg -- to require that biology teachers tell their classes that "Darwinism" was "just a theory" (that is, a dodgy theory), and recommend OF PANDAS AND PEOPLE to provide an alternate view. The exercise was essentially textbook stickers all over again: WARNING! HAZARDOUS TO YOUR HEALTH!

While the backers of the measure believed they were promoting "academic freedom" in a very modest and prudent way, that wasn't how the affected Dover high school teachers saw things. From their point of view, it was as if they were teaching classes on medicine, and had been required to read a statement that not only called the credibility of their lessons into doubt -- but then recommended snake oil as an alternative. The teachers refused to read the statement. School administration officials read the statement instead.

A monster uproar that made international press followed. One of the school board members who had backed the exercise recalled later he was astounded at the fury of the reaction, saying: "It was like we'd shot someone's dog." Given the long history of bitter legal feuding over Darwin, it shouldn't have been a surprise. Eleven parents, backed up by the ACLU and other organizations, promptly filed a suit against the school board, claiming it was an attempt to impose a religious doctrine on public education.

The defense was backed by the Thomas More Law Center, a public legal organization that worked on conservative causes. The case was named KITZMILLER VERSUS DOVER AREA SCHOOL DISTRICT, Tammy Kitzmiller being one of the parents pressing the case. Testimony was given by Michael Behe and other creationists for the defense, with prominent biologists testifying for the prosecution. Late in 2005, US District Court Judge John E. Jones III declared the efforts of the Dover school board a violation of the Establishment Clause, releasing a 139-page decision. Judge Jones ruled that the defendants had a clearly religious agenda, pointing out that ID "violates the centuries-old ground rules of science by invoking and permitting supernatural causation." He elaborated:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

Both defendants and many of the leading proponents of Intelligent Design make a bedrock assumption which is utterly false. Their presupposition is that evolutionary theory is antithetical to a belief in the existence of a Supreme Being and to religion in general. To be sure, Darwin's theory of evolution is imperfect. However, the fact that a scientific theory cannot yet render an explanation on every point should not be used as a pretext to thrust an untestable alternative hypothesis, grounded in religion, into the science classroom or to misrepresent well-established scientific propositions.

END_QUOTE

There was still no way to serve spamloaf to the courts and convince the judges it was steak. Judge Jones -- whose had solid conservative credentials, having been appointed to the district court by the Bush II Administration, with his nomination sponsored by Senator Santorum -- edged into the scathing in his dismissal, calling the efforts of the creationists in Dover an exercise in "breathtaking inanity" and saying in that the whole thing was an "utter waste of monetary and personal resources."

Jones was bitterly attacked for his decision, and later had to receive Federal protection when threats were made against him and his family -- much to his astonishment, the judge later commenting that he would have expected threats over a trial against drug dealers, but not over an Establishment Clause case.

In the wake of the Dover decision, the governor of the state of Ohio asked the board of education to review the "teach the controversy" language that had crept into the state's educational curriculum; a few weeks later, the board removed the language. During the Dover trial, the Kansas state board of education -- which in 1999 had notoriously attempted to flatly eliminate evolutionary teaching from the school curriculum, only to backtrack the next year in the face of loud protests -- had introduced "teach the controversy" language written up with assistance from the Discovery Institute into the curriculum. By early 2007, the language had been withdrawn in the face of further protests.

* Since the 2005 decision in the Dover case, creationist activism has generally disappeared. There was, for a time, efforts in various state legislatures to push through "academic freedom" bills, giving teachers the "green light" to discuss the "strengths and weaknesses" of MET -- "teach the controversy", having become controversial in itself, had to be abandoned -- as well as challenge climate change science, or anything else the anti-science fringe dislikes.

These bills never amounted to much one way or another -- being called "Dover traps", encouraging creationist teachers to speak out, while not actually giving any protection against an Establishment Clause challenge. The Dover case was a financial disaster for the local school board; anyone trying to push a similar case is soon informed that it's not a good idea.

Lawsuits in the courts have similarly gone quiet. In 2013, a creationist group in Kansas pressed a suit claiming that evolution was a "secular religion" That approach had gone nowhere twenty years earlier in the Peloza case, and the court simply dismissed the protest. The creationist group then appealed to the higher court, which similarly dismissed the appeal as without merit in 2016.

It now appears that creationism has shot its bolt. It was always a marginal phenomenon, having no traction with the science community and not all that much with the general public. Creationist activism never accomplished much; finally, the creationist community then turned to a policy of evasion, creating ID and denying it was creationism. ID was a tactic of desperation, the bottom of the barrel of tricks.

In 2013, Stephen Meyer of the Discovery Institute, perceiving rightly that the ID movement had run out of what little steam it ever had, published a weighty creationist tome titled DARWIN'S DOUBT in hopes of reviving it. The book was popular with the creationist community, with claims that it radically overturned evolutionary science. Except for a few sharply critical reviews from scientists -- which Meyer shrugged off -- DARWIN'S DOUBT had zero impact on the science community, and was ignored by the general public.

The US election of 2016 marked the effective end of creationism. The election led to a tsunami of Right-wing activism against all doctrines judged liberal, such as diversity-equality, reproductive freedoms, LGBT rights, and climate change. The irony was that, in all the furor, creationism was barely mentioned -- and the Right-wing activism accomplished nothing over the longer run but to provoke a backlash that sent evangelical Christianity into decline. Creationism will never go away completely -- but now it's disappeared below the noise level, and seems likely to stay there.

BACK_TO_TOP* In the end, creationism was never able to advance beyond its roots. The variations of complexity arguments always ended up being much the same, technical details being of little significance, as the argument of the Reverend Paley: organized complexity is a marker of the work of a Watchmaker, a Cosmic Craftsman, an Intelligent Designer, or some other equivalent Unseen Agent.

Paley appears to have been a decent gentleman, and it's a bit of a pity that his argument is now seen as a transparent fallacy. His fallacy was not in suggesting that complexity might imply a Watchmaker; it might. His fallacy was that he was simply reasoning by analogy, believing that since humans design elaborate artificial objects, then elaborate natural objects such as organisms had to be the work of an Unseen Agent.

Reasoning by analogy can be surprisingly effective, it seems mostly as a way of "thinking outside of the box", but that's a bit surprising, since it has an obvious limitation. Analogies are comparisons, often for illustrative purposes, between two things that are similar in some ways but not in others -- if the two things are either entirely different or exactly the same, there's no useful analogy between them. Simply because two different things are similar in some ways doesn't imply they are necessarily similar in others; for example, there are many similarities in subsystems and construction between a car and a private airplane, but that hardly proves that an ordinary car can fly in any useful sense of the word.

The only way to determine what is the same and what is different about the two things is to go check and see where they are the same and where they differ. Indeed, no abstract argument of any sort about how the Universe is supposed to work proves anything in itself. Some arguments are obviously more credible than others, but no matter how well-constructed the argument, we always have to go check to see if we really got it right. How otherwise would we know if we were missing something?

Paley's fallacy was that he didn't check -- and more importantly, he had no way of doing so. He had come to a conclusion he could not validate, and so he had nothing but an unproveable speculation. Our intuition is a product of experience; if we have no experience in some matter, we have no workable basis for intuition of it, and all we can do is make completely unsupported guesses. Paley's guess didn't address the question of whether organisms could have arisen by some spontaneous natural process -- he gave no thought to whether they could have or not, he simply leaped to an answer and proclaimed they had to be the work of a Watchmaker, relying strictly on an analogy with human artifice. Paley was playing with only a joker card in his hand, having absolutely no other basis for believing, no experience, no way to confirm that organisms are the work of a Cosmic Craftsman.

Of course, in pointing out that organisms are the work of a Cosmic Craftsman, Paley necessarily suggested that the Universe as a whole, with its stars and planets, must be the work of a Cosmic Craftsman as well -- a distinction that is often muddied in discussions of his argument. Paley's reasoning certainly seems no stronger in its extension to the entire cosmos; other than his weak analogy, he had no evidence that intelligence had any significance whatsoever in the Universe. As David Hume put it:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

[If] we were to take the operations of one part of nature upon another, for the foundation of our judgement concerning the origin of the whole ... why select so minute, so weak, so bounded a principle, as the reason and design of animals is found to be upon this planet?

What peculiar privilege has this little agitation of the brain which we call thought, that we must thus make it the model of the whole universe? Our partiality in our own favour does indeed present it on all occasions; but sound philosophy ought carefully to guard against so natural an illusion.

END_QUOTE

Hume actually did agree that the Universe seemed to demonstrate some sort of craftsmanship. He simply pointed out that in making that assumption, we assume on the basis of comparisons with our own modest constructions that intelligence is some underlying principle of the Universe -- like the gravitational or electromagnetic force -- when it isn't demonstrable that it is. Given the lack of evidence, invoking the Watchmaker ends up being an argument of ignorance, its only support being insistence that there is no alternative. Hume's concession was meaningless, and he knew it; he made it entirely clear that all Paley was offering was a useless conjecture.

Darwin revealed a particular difficulty with Paley's argument. In proclaiming that organisms were the products of a Cosmic Craftsman, Paley also simply assumed they were static, that they had been more or less created in their present form, failing to consider the possibility that they could spontaneously evolve and adapt. However, when we examine the Universe in general, it is obviously not static at all. It is evident that landscapes, planets, stars, galaxies, the cosmos itself all spontaneously evolve in various ways, their current forms not being the same as their earlier forms nor the same as the forms they will have in the future. Even the atoms themselves may evolve, with heavy elements synthesized in stars while elsewhere radioactive isotopes decay to daughter isotopes.

We observe evolution in the broad sense as a normal condition of the Universe. We would have no reason to assume if we found a rock that it had been created in its present form at the beginning of the world, and there is nothing that Paley said to suggest that we should assume so. Paley's assertion was that the natural laws of the Universe reflect a Watchmaker; but even humoring that argument, there was nothing in his reasoning that asserted its elements could not spontaneously change. By extension, as far as evolution is concerned, Paley's argument means nothing: if we so wished, we could amuse ourselves by saying evolution was created by a Watchmaker as well, and there's not a thing in his argument to contradict that assertion.

Computer programs to perform evolutionary simulations are nothing unusual; we can easily establish a link between human artifice and evolutionary process that, on the basis of Paley's reasoning by analogy, is every bit as convincing, has as much basis in the facts, as any other attempts to declare the work of an Intelligent Designer in nature through analogy with human artifice. However, all that does is underline the hollowness of the idea, since then the involvement of the Cosmic Craftsman becomes excess baggage, and creationism has lost its flimsy case against evolution. Revealingly, few on either side of the argument like the slogan: "God Intelligently Designed evolution."

* The Paley fallacy does have a certain intuitive appeal, but it tends to lose its appeal on closer examination. Although creationists persistently denounce "scientific materialism", in doing so, they disregard just how crudely mechanistic Paley was in his own thinking, comparing the workings of machinery to the workings of organisms -- despite the fact that the resemblance between a biosystem and any machine ever built by humans is slight. Machines, unlike organisms, do not in any significant sense reproduce or grow or rebuild lost parts of themselves. No two organisms of the same species resemble each other as much as two examples of the same product, and by that same coin organisms work perfectly well with components featuring a range of variance that would be intolerable in a machine.

Machines that resemble biosystems even superficially are unusual, lacking the rectilinear and rigidly structured configurations of more typical manufactured items, and are often referred to as "organic" in appearance. Of course we can also build machines that look like organisms -- a windup toy to imitate a hopping kangaroo, for example -- but what does that prove? When we do build machines that are, inadvertently or by intent, similar in appearance to organisms, that hardly establishes that the organisms they resemble must have been put together by an Intelligent Designer. If humans imitate nature, does that mean nature must imitate humans? Indeed, humans so often imitate or exploit nature in their inventions that in many cases humans are simply cribbing, sometimes very deliberately, from nature in the first place.

In addition, if organisms are compared to machines, while acknowledging that unlike machines they grow and reproduce, then nothing in that line of reasoning rules out the idea that organisms also spontaneously adapt and evolve exactly as MET says they do. If, as creationists like to say, the ability of organisms to reproduce, grow, and repair themselves demonstrates that they are even better designed than human-made machines, then an ability to spontaneously adapt and evolve makes them better designs still, and creationism in all its variations once again disappears in a poof of irrelevance.

Besides, why should complexity be thought of as a unique marker of an Intelligent Designer? Given a system that implements some function, the simpler one can be seen as demonstrating better craftsmanship; and more to the point, humans artifacts can be marked by their unnatural simplicity. If we were to throw a ping-pong ball among a pile of smooth pebbles, we'd have no problem identifying what in the pile was artificial and what was natural -- but in this case, the marker of craftsmanship is the simplicity of the ping-pong ball. The ping-pong ball's dimensions and composition are much more uniform than those of the pebbles; would anyone sensibly claim that the relative elaboration of the pebbles, with their varied dimensions and much more complicated compositions, makes them more obviously artifacts than the ping-pong ball?

If we accept reasoning by analogy from human design, then why isn't simplicity also a marker of an Intelligent Designer? We could build a wall of bricks, or of flat rocks we scavenge up from the landscape. Bricks resemble rocks far more closely than machines resemble organisms -- but nobody sensibly claims that proves flat rocks must be the work of a Watchmaker, even though their similarity to a human-made artifact like a brick is much closer than that of organisms to machines.

The assertion that complexity is a marker of a Cosmic Craftsman ends up failing even on the basis of reasoning by analogy, since reasoning by analogy suggests that simplicity is just as good an indicator. The complexity argument is no more than an argument of incredulity, a simple assertion that simple objects can be accounted for by the laws of nature, but complex objects cannot.

* The ultimate failing of Paley's line of reasoning was that in claiming nature reflects a Watchmaker, he could provide on the basis of his argument no details whatsoever of that entity. Unseen Agents are like that. As Hume put it:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

In a word ... a man who [proclaims the necessity of an Intelligent Designer] is able perhaps to assert, or conjecture, that the universe, sometime, arose from something like design: but beyond that position he cannot ascertain one single circumstance; and is left afterwards to fix every point of his theology by the utmost license of fancy and hypothesis.

END_QUOTE

After all, if we found a watch, we would be able to inspect it and determine what craftsman built it, and in principle learn everything about its design and construction. If we find a butterfly and claim it must be the work of a Cosmic Craftsman, we still know nothing specific about that entity, what that entity did, or why that entity did it. All we can say is that there's some vaguely-defined Unseen Agent of some sort who did things by magic, or some mysterious unexplainable process equivalent to it, and we won't be a bit wiser than we were before.

As far as religion is concerned, all religions, even those created as a gag, can trot out Paley's argument to argue for whatever Unseen Agent they prefer, and each can defend their conclusion with the same self-assurance as another. The only response that can be made to that fact is to argue the relative merits of different religions -- which can be done, but nobody could plausibly claim it as a matter of relevance to the sciences, or for that matter to anyone but partisans of different religions. As far as science is concerned, Paley's argument is simply useless; it provides no specifics, and no scientific theory works any differently whether we assume the Universe is the work of a Cosmic Craftsman or not.

Paley's apologists insist that his argument cannot be shown to be wrong, which is true. However, by that same coin it is also inconclusive. Given the weakness of Paley's argument, it is not surprising that as Richard Dawkins has pointed out, by showing that natural objects that appear to be the products of a Cosmic Craftsman clearly aren't, MET establishes an inconvenient precedent that undermines Paley's tenuous argument in general. Hume suggested that those enthusiastic for the interventions of an Unseen Agent end up undermining the case for the Deity, not supporting it:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

They consider not that, by this theory, they diminish, instead of magnifying, the grandeur of those attributes, which they affect so much to celebrate. It argues surely more power in the Deity to delegate a certain degree of power to inferior [agents] than to produce every thing by his own immediate volition.

It argues more wisdom to contrive at first the fabric of the world with such perfect foresight that, of itself, and by its proper operation, it may serve all the purposes of providence, than if the great Creator were obliged every moment to adjust its parts, and animate by his breath all the wheels of that stupendous machine.

END_QUOTE

The supposed tinkerings of a Watchmaker are merely comical, cheap tricks, implying a lack of skill, the Universe becoming a clumsy contraption that will simply fall over if left unattended. Certainly the invocation of an Unseen Agent is irrelevant to the sciences, since we know of no laws of nature that require the inherently unpredictable meddling of such an entity to work. In fact, it would be hard to think of them as predictable laws if they did; and on the other side of that coin, if the actions of the Intelligent Designer were predictable, we wouldn't be able to distinguish them from the action of natural law.

Nobody sensibly believes that thunder and lightning are caused by the pounding of Thor's hammer any longer, or more evasively claims they're due to some mysterious action of an "Intelligent Thunderer". If anyone protests that's a silly example, the response can only be that's exactly correct, and ask why a humanized deity such as Thor is all that different from an unavoidably humanized Intelligent Designer.

Despite these obstacles, Paley's weak reasoning by analogy persists. In modern times, just as Paley made a comparison between organisms and a watch, creationists similarly make comparisons between, say, the genome and computer programs -- but it's just the same argument, the watch being the 18th-century notion of high technology, computers not having been invented at the time. Such analogies appear so strong that their advocates fail to realize they're mesmerized by a scene in a mental mirror that imposes human ways on a Universe that, as all agree, isn't run by humans. Paley's argument hardly amounts to anything more than seeing faces in clouds.

In the novel THIEF OF TIME, the British fantasist Terry Pratchett provided an ingeniously twisted read on Paley's Watchmaker argument. Pratchett wrote of the monk Lu-Tze and his student Lobsang on a journey through the woods. Lu-Tze is chatting with Lobsang, who asks the monk:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

"Er .... why are we whispering?"

"Look at the bird."

It was perched on a branch by a fork in the tree, next to what looked like a birdhouse, and nibbling at a piece of roughly round wood it held in one claw.

"Must be an old nest they're repairing," said Lu-Tze. "Can't have got that advanced this early in the season."

"Looks like some kind of an old box to me," said Lobsang. He squinted to look at it better. "Is it an old .... clock?" he added.

"Look at what the bird is nibbling," suggested Lu-Tze.

"Well, it looks like .... a crude gearwheel? But why -- "

"Well spotted. That, lad, is a clock cuckoo. A young one, by the look of it, trying to make a nest that will attract a mate. Not much chance of that .... see? It got the numerals all wrong and it's stuck the hands on crooked."

"A bird that builds clocks? I thought a cuckoo clock was a clock with a mechanical cuckoo, which came out when -- "

"And where do you think people got such a strange idea from?"

"But that's some kind of miracle!"

"Why?" said Lu-Tze. "They barely go for half an hour, they keep lousy time, and the poor dumb males go frantic trying to keep them wound."

END_QUOTE

Some may laugh at this story, others may sneer, but all agree that the notion of a "clock cuckoo" is silly. Of course it is. Everyone knows that nature doesn't produce machines as humans understand them, the idea is obviously ridiculous. That being so, then why should anybody take comparisons between clocks and watches -- or computer programs or recipes or whatever -- and biosystems seriously?

Bob may insist that a butterfly had to have been the work of an Intelligent Designer, but what reason would Alice have to agree? All Bob can do is play the Paley card, comparing organisms to machines, and then proclaim that it is intuitively obvious. Alice can ask in reply why it's supposed to be obvious -- the only support for the idea is an analogy with human construction of machines, and that analogy is literally a joke: Do cuckoos really build cuckoo clocks?

BACK_TO_TOP* Consider the possibility of developing a computer simulation of the entire Earth, starting with its early history, based completely on the basic laws of physics and chemistry. If we were to tell the simulation RUN from time-zero, what would we see happen on the Earth? Creationists would insist nothing would happen, that the complexity of the biosphere could not emerge from a lifeless ball of rock through all its history.

Such a simulation is impractical to the point of impossible. However, suppose we simulate a small world that operates using a few simple laws. On the face of it, we have even less reason to think that organized complexity will emerge from such a simulation, there being so little to start with. Fortunately, it's easy to implement such a world and see what it actually does.

That was effectively the starting point for the "Game of Life" or simply "Life", devised by British mathematician John Horton Conway in 1970. It envisions a grid of squares or "cells", in which cells can be set to two colors. It doesn't matter what two colors, we can specify green and white, with green designated "live" and white designated "dead". Given some pattern of live cells in the grid, that pattern will give rise to a next generation as follows:

It's not much of a game, really; the only way a user can "play" it is by selecting an initial condition, then letting it run to see what happens. Incidentally, Life is an example of what is known as a "cellular automaton"; there are others with different rules, not discussed here.

Any implementation of Life on a computer will use a grid of fixed size, say 256 by 256 cells. There's the question of boundary conditions: while an implementation may specify that Life evaluate a cell on the boundary of the grid as having "dead" cells beyond the boundary, it is generally more convenient to "wrap around", with cells on the top boundary using cells on the bottom boundary as neighbors; and cells on the right boundary using cells on the left boundary as neighbors. Wraparound is the assumption used here.

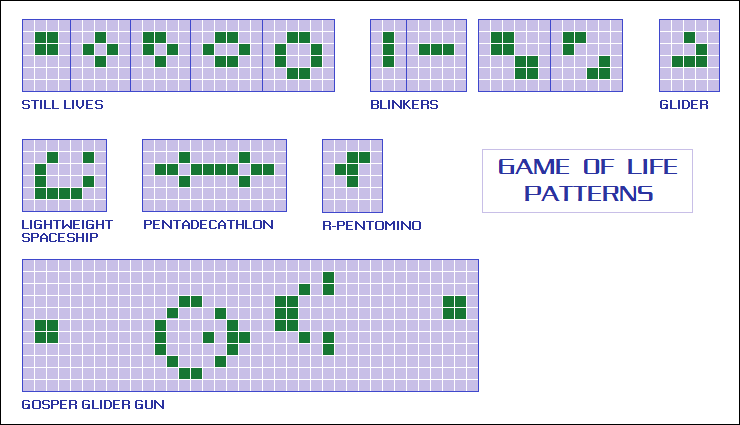

On implementing Life, Conway found that he had designed a surprisingly rich world. To be sure, not all patterns in the Life World proved all that interesting: often the patterns died out -- or ended up static, unchanging. Some became "Blinkers", switching between two states with each generation; for example, three live cells in a column would become three live cells in a row, then three live cells in a column again.

Getting more interesting, Blinkers proved to be just a simple subset of oscillating patterns, with repetition periods of three generations or more. One simple pattern, named the "Pentadecathlon", had a repetition period of 15 generations. Working from there, oscillating patterns were found that moved across the grid from generation to generation, migrating to one edge and then emerging from the other. These were named "Shapeships", the simplest being the "Glider".

Now getting really wild, there proved to be a pattern that could generate a stream of Gliders, this pattern being called a "Glider Gun" -- though in the wraparound Life World, eventually a glider would pass over the edge of the grid, to come back around and crash into the glider gun. Patterns were also found to generate more elaborate Spaceships, and patterns have been found that generate themselves. It is even possible to define logic elements using Life patterns, and construct simple logic systems.

It seems there is no limit to the complexity of the Life world, even with a small 256 by 256 grid. In practice there isn't, the total number of possible patterns being 2^65,536 == 10^19,728. For a standard of comparison, the number of atoms in the Universe is estimated at roughly 10^80, give or take two orders of magnitude. Of course, the same pattern will be repeated in four orientations, rotated 90 degrees, and have mirror images for each, but that only cuts down the total by 8 == 2^3. In the wraparound world, if a pattern is referenced to one particular cell, that reference cell can be on any grid cell, cutting the total number of patterns down further by 65,536 == 2^16.

However, even factoring in such redundancies only trivially reduces the total number of patterns. Granted, nothing will happen in the 256 x 256 Life World that can't be done with 65,536 bits of information; nothing is going to acquire a life of its own there, though it may seem a bit like it does at times. Nonetheless, not only do we not know what can happen with those 65,536 bits, we never will. Even if we consider only, say, 10^100 of the patterns, a vanishingly small subset of the total, are interesting, the Life world space still remains far too vast for us to ever explore it all.

Creationists insist that there's no way that complexity can arise spontaneously from the interactions of inert matter; but the real world is vastly bigger than the little toy Life World described here, and has far more rules of operation. It doesn't seem hard to believe that complexity would spontaneously arise in the real world; it seems hard to believe that it wouldn't.

Of course, creationists will immediately shoot back that the Life World is an "intelligent design", created by John Conway, thereby proving there must be an Intelligent Designer after all. In reality, we can construct software models and other representations of absolutely everything in the world, so that proves nothing at all. By this same reasoning, we could conclude that, since a toy panda is built by a factory in China, then a real panda must have come from a factory in China, too.

In any case, we know for an indisputable fact that the Life World was created by John Conway. What facts do we have about the ultimate origins of the real world? We have no substantial evidence at all, and so it could have been created by anything or anybody; which means nothing or nobody in particular; which is the same as nothing.

BACK_TO_TOP* I had misgivings about writing this document, having doubts it was a good use of time. I knew even at the outset creationism was a useless bore, entirely lacking in substance, nothing but trolling -- loud assertion of blatant and often incoherent nonsense, with no intent beyond provocation and picking fights, in which skeptics then dashed themselves in futility against the "invincible ignorance" of creationists.

This document started life as notes from an installment on Mark Chu-Carroll's blog, with more materials flowing in from comments by Jeff Shallit in his blog, along with comments taken from the writings of Richard Dawkins here and there. Of course, my studies of David Hume were useful as well. The revision I performed in 2017 benefited substantially from readings of the philosopher / cognitive researcher Daniel Dennett, primarily with regards to the very good case he has made for considering evolution as a design process -- and indeed an intelligent, if not mindful, one. I also leveraged off his discussion of Conway's Life world. The 2024 revision was the effective end, putting the subject to bed.

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 apr 10 / Released as EVOLUTION & INFORMATION.

v1.1.0 / 01 jun 10 / Expanded, went from one to two chapters.

v1.2.0 / 01 aug 10 / General cleanup.

v1.2.1 / 01 sep 10 / Minor fixes.

v1.2.2 / 01 dec 10 / More minor fixes.

v1.2.3 / 01 apr 11 / Still more minor fixes.

v1.3.0 / 01 jan 12 / Retitled as EVOLUTION, ENTROPY, & EVOLUTION.

with expanded focus on thermodynamics.

v1.4.0 / 01 jun 12 / Replaced "critics" with "creationists".

Extensive tuning of SLOT & Paley fallacy arguments.

v1.4.1 / 01 dec 12 / Minor update to track INTRO TO EVOLUTION.

v1.4.2 / 01 oct 13 / Review & polish.

v2.0.0 / 01 sep 15 / Added short history of creationism, 4 chapters.

v3.0.0 / 01 aug 17 / Retitled as EVOLUTION, INFORMATION, & THE PALEY

FALLACY; added discussion of Conway's Game of Life.

v3.1.0 / 01 apr 18 / Clean-up.

v4.0.0 / 01 mar 20 / Retitled to EVOLUTION, INFORMATION, & CREATIONISM.

v4.1.0 / 01 sep 21 / Review & polish.

v4.1.1 / 01 apr 23 / Review & polish.

v5.0.0 / 01 apr 24 / Closing out the argument.

BACK_TO_TOP