* Hitler had foreseen correctly that the Soviets and the Western allies would have a falling-out, but it happened much too late to do him any good. As the hot war against the Nazis faded away, the Cold War between East and West began to take root. In the meantime Stalin, the distraction of crushing Hitler having ended, turned his attention back to the interrupted war of domination against his own people.

* All Soviet citizens celebrated the new peace, even those in the Gulag, though the celebrations there were more mandatory than spontaneous. However, in Stalin's USSR, "peace" was a strictly relative term. Stalin had been forced to relax his grip to deal with Hitler. Now that Hitler was history, Stalin could tighten it again.

There was, for example, the troublesome matter of the overly popular and independent Zhukov. In his press conference with international reporters after the fall of Berlin, Zhukov made no mention of Stalin until queried by reporters. It is unlikely that was the straw that broke Stalin's back, but it could not have made Stalin feel any better about Zhukov. Koba could also not have been happy with the admiration that Zhukov was being given in the British and American press. Stalin might call Zhukov his Suvorov, but listening to others do it was irritating.

Beria sent his lieutenant Viktor Abakumov, head of SMERSH, to Germany to arrest anyone who might be able to discredit Zhukov. Zhukov unsurprisingly found out and bluntly gave Abakumov the choice of immediately going back home under his own power or being escorted home by Zhukov's soldiers. Beria, infuriated, then moved to more direct action, having some of Zhukov's aides arrested and tortured to give false testimony against their commander. They testified in fine Stalinist tradition that Zhukov was plotting against the Great Leader, and that Zhukov had established secret contacts with American General Eisenhower.

Zhukov's friendly relationship with the folksy and amiable Eisenhower was in fact obvious. Eisenhower visited Moscow in August 1945, with Zhukov acting as his escort, with the two generals greeted by roaring applause wherever they went. Eisenhower even put his arm around Zhukov's shoulder. To Stalin's mind, that was essentially treason in itself -- though Koba himself was agreeable to Eisenhower, apologizing to the visitor for the "last minute change in plans" when the Red Army moved on Berlin instead of Central Europe.

Imprisoning or executing Zhukov was not prudent; after all, he was one of the heroes of the day. Zhukov was granted the honor of leading a victory parade in Moscow on 24 June 1945, romantically galloping in front of the troops on a gray charger, though the celebration was dampened by downpours of rain. Stalin's son Vasily told Zhukov that Stalin had wanted to perform the ride himself, but the horse had thrown him when he tried to get the hang of riding it, and so Koba decided to let Zhukov ride instead.

Zhukov could be put out of the way in a subtler fashion. At the end of 1945, he was denounced, demoted, and assigned to military bureaucratic oblivion, given meaningless posts in Odessa and the Urals. He would not be rehabilitated until after Stalin's death. Less prominent generals got worse treatment, with dozens arrested. Air Marshal Novikov was broken in rank, stripped of his decorations, and sent to prison. General Telyagin, Zhukov's executor in the conquest of Berlin, complained about looting by NKVD formations, and so Beria saw to it that Telyagin was sent to prison for 25 years. These men, too, would have to wait for Stalin's death to end their punishments.

* Germany was divided into separate zones of control, each administered by one of the victorious nations, and Berlin, deep in the Soviet zone of control, was split up similarly, the Western Allies to arrive in time. Berliners were starving. Soviet citizens were going hungry at the time as well, but Stalin understood the need to maintain his image of benevolence, and priority was given to sending subsistence rations to Berlin. Special newsreels were put together displaying young children who had been separated from their parents, and shown to German citizens in hopes of reuniting families.

Those children from the East who had been taken away by the Germans were returned home, though in many cases there was little but ruins waiting for them. They carried with them identification numbers tattooed upon them by the Germans, and also the stigma of having been, however involuntarily and innocently, exposed to foreign infection. In Stalin's Soviet Union, that was crime enough.

Red Army prisoners of the Germans, and the Soviet citizens who had been carted off for Nazi slave labor, were also objects of suspicion. Even those prisoners who had been given weapons and thrown back into the fight against the Germans immediately after being freed from camps got little credit for it. The prisoners and slave laborers had looked forward to liberation, only to find themselves regarded with contempt by Red Army troops, who abused them, robbed them, and even raped the women, calling them "whores of the Germans".

That was almost the least of their worries. The NKVD set up a hundred holding camps where returnees could be held and interrogated. If the interrogators didn't like the answers they got -- and they were inclined to not like them, no matter what they were -- the victim was going to suffer. Stalin invoked his agreements with the Western Allies to ensure that Soviet citizens and prisoners who had fallen into their hands were returned to the security of their own homeland.

The Allies returned the Hiwis, Soviet subjects who had fought against Stalin. General Krasnoff, Ottoman of the Don Cossacks, had fought against Bolshevism since 1918, and during the war led an army of 70,000 Cossacks to fight alongside Hitler's forces. At the end of the war, Krasnoff and his surviving Cossacks surrendered to the British. The British promised not to turn them over to Stalin, but Stalin insisted. The British packed up the Cossacks, who in some cases were accompanied by their families, and took them to a bridge.

The NKVD was waiting for them on the other side. The prisoners were ordered to walk across the bridge. The officers were shot immediately by the NKVD in full view of the British. Some of the Cossacks threw themselves off the bridge, which was about a hundred meters above the river. Those who had not been shot or had committed suicide were packed into a train and hauled away. The British handed over tens of thousands of Hiwis in all.

The Americans similarly returned the small number of Hiwis who had been kept in POW camps in the USA. On 29 June, captives at Fort Dix, New Jersey, started a riot, attacking the guards, but only in hopes of being killed: "Shoot us! Shoot us!" -- they cried, pointing to their hearts. The riot was suppressed with no guards or prisoners killed, except for three who hanged themselves. The others were sent back to Soviet custody.

Some American officials had deep misgivings about doing so, being under few illusions about what would happen to the returnees, but there was nothing they could do. The Soviets were still an ally of America, and the USA was bound to honor agreements made with the USSR; possibly more significantly, the Soviets had liberated thousands of American and British prisoners, and could hold them hostage if the Hiwis were not handed back. Most of the Hiwis were not executed, but they would have a very hard time of it in the Gulag.

BACK_TO_TOP* While the trains took traitors, both suspected and real, eastward into the far-flung network of the prison camps, a train took Stalin west to meet with the other Allied leaders at Potsdam, Germany, not far from Berlin. Beria was entrusted to ensure Stalin's safety and paved the way with a massive security operation, with 17,000 troops guarding the rail route. Stalin did not believe in taking unnecessary chances.

At Potsdam, Stalin was at the peak of his powers. As if in preparation for his triumphal role there, in late June, PRAVDA had announced that, along with being premier and party secretary, Stalin had become a "generalissimo". The conference ran from 17 July to 2 August 1945, Stalin conferring with the other "Big Three" leaders, Winston Churchill and the new American president, Harry Truman. Truman, not being thoroughly briefed on matters, left most of the work to his secretary of state, James Byrnes. The meeting was effectively a follow-up to the Yalta Conference, with specifics of the postwar order of Europe nailed down -- though as it turned out, somewhat more by default than by agreement.

The processes of demilitarization and "democratization" of Germany were clarified, as were the four occupation zones of the victorious Allies, and the westward adjustment of the Polish and German borders. The matter of resettling six million ethnic Germans who had been evicted from Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia, in general in an abrupt and harsh manner, was addressed. Hitler had made a great deal of noise about the status of German-speaking minorities in Eastern Europe, and now the problem was being resolved in a way the Fuehrer had not quite anticipated.

The Western Allies handed Stalin a plum by recognizing the Communist Lublin government as the legitimate government of Poland. Churchill and Truman were not happy about the effective exclusion of the London Poles from the Polish government, but there was little they could do about it; Churchill was tired of fighting Stalin over the issue -- all the more so because the London Poles complained incessantly, without suggesting any realistic options for what Churchill could do. There really weren't any. Soviet control over the rest of Eastern Europe was not challenged. Stalin also pushed for a Soviet military presence in the Turkish straits, in order to guarantee Red Navy access from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean; Molotov had warned him that wouldn't fly, and it didn't. It was a shrug. Stalin was holding as good a hand of cards as he could ever expect to have, and he wanted to see what he could get away with.

More significantly, the Western Allies were not agreeable on the question of German reparations to the USSR. FDR had agreed to reparations in principle at Yalta, with the Soviets to obtain compensation from Germany as a whole, but now the idea seemed much more problematic. Although Stalin could take satisfaction in Allied leaders making the pilgrimage to a land he had conquered, the visitors also saw and were dismayed by the massive looting of Germany by the Soviets then in progress.

The Soviet demand for reparations, though understandable, was a fantasy. The Germans were in a destitute condition themselves, the worst-off being the ethnic Germans who had been evicted from their homes in the East. What sense did it make to exact reparations if America then had to pump billions of dollars of emergency aid into Germany to keep the people from dying of starvation? It made much more sense to get the German economy back on its feet so the Germans could feed themselves. Indeed, an impoverished Germany would hold down the rest of the economy of Europe.

Soviet officials did not care for the moralistic lectures of their Western counterparts on reparations, replying with lists of advanced German weapons hauled off by the British and Americans. There was a certain amount of justice in that accusation; the Americans had scrambled into parts of Germany to be occupied by the Soviets, carting off materiel before the Red Army arrived. American bombers had even, on 15 March, bombed an evacuated German nuclear processing plant at Oranienburg to level it before the Soviets could seize it. The value of the captured technology was far from trivial -- but then again, the plan was to demilitarize Germany, meaning the weapons would have otherwise been disposed of, and the Western Allies did not run off with materiel the Germans needed to support themselves.

As far as Western officials were concerned, they could do nothing if the Soviets looted the section of Germany under their control, but they were not agreeable to giving Stalin loot from the rest of Germany. Allied plans envisioned that the German state would in principle remain intact, but given that each side restricted the other from its zone of control in Germany, the reality was that Germany would remain divided for decades. The principle of the complete demilitarization of Germany would also fall by the wayside.

Truman pressed Stalin to help deal with the Japanese, and he was agreeable, saying planning was already in motion. The Soviet Union would move against Japan in mid-August. That was satisfying to Truman, but he was puzzled when he dropped hints on 24 July to Stalin that the US had developed a powerful new weapon -- the first atomic bomb had been tested on 16 July, the starting day of the conference -- and Stalin seemed completely disinterested.

Actually, the American nuclear development organization had been thoroughly infiltrated by Red spies; Truman hadn't been briefed on the program until after Roosevelt's death, while Stalin had known about the Bomb in detail long before Truman even knew it existed. Stalin complained in private over the failure of the Western Allies to inform him of the atomic bomb program -- indifferent to the fact that he had never told them anything but what he felt they needed to know, and lied to them when expedient.

On 26 July, the Americans, British, and Chinese issued the "Potsdam Declaration", calling for the unconditional surrender of Japan, providing assurances that the Japan would remain a sovereign if demilitarized state in the aftermath, and the Japanese people would not be enslaved or exterminated. Failure to comply would result in "prompt and utter destruction", a threat that Truman was now able to back up. The Japanese ignored the declaration. The Soviets were unhappy that they were not consulted on the matter -- but as they were told in reply, the USSR was not at war with Japan at the time and had previously avoided public declarations on the matter. The response was hard to argue with, but they still felt snubbed, resulting in a chilly conversation between Byrnes and Molotov.

Late in the meeting, Churchill returned home to Britain to see out the result of a general election. The result was that he was replaced by Labour's Clement Atlee, who took Churchill's place at Potsdam for the final days of the conference, though Atlee had neither the knowledge or the stature to contribute much to the proceedings. Revealingly, Stalin was astounded that Churchill had been evicted from office, demonstrating Koba's complete inability to comprehend the notion of representative government. He had long been contemptuous of the way his Western counterparts worried about the electorate, judging it a ploy; how could a power politician like Churchill be simply thrown out of office so unceremoniously? How could Churchill have allowed anyone to do such a thing to him? Heads would have all but literally rolled if anyone attempted to remove him from his position.

Stalin left Potsdam with causes for satisfaction, though he didn't get everything he wanted, the lack of agreement on reparations being a particularly sore point. However, it was all but the last act between the two sides where they resembled allies. In an attempt to resolve differences, Truman managed to persuade Harry Hopkins to make a trip to Moscow to talk things over with Stalin. Hopkins arrived on the evening of 25 May and had talks with Koba over two weeks' time.

Poland was top of the agenda, but Hopkins could do no more than ask Stalin for restraint -- Truman having made it clear to Hopkins that the US government understood the Soviet Union was going to do what it liked in Eastern Europe. All Hopkins and Truman could expect was a few cosmetic concessions from Stalin on various small issues for political cover, and Koba was of course flexible enough to give away little favors that cost him nothing. Hopkins returned home to effusive thanks from Truman, something he'd never gotten from FDR, with Hopkins dying four months later.

Encouraged by the fact that the Americans had effectively given up their objections to Soviet actions in Eastern Europe, Stalin went after more, demanding a border adjustment with Turkey and again pressing for Soviet military installations in the Turkish straits. He also arranged for an uprising of Iranian Azeris in an attempt to adjust the USSR's border with Iran. Stalin was merely probing; if he got what he wanted, fine, if he didn't, nothing lost.

In fact, none of these three exercises amounted to much. The Soviets obtained nothing from Turkey; Koba gave up his Iranian adventure a year later, following the withdrawal of Red Army occupation troops from Iran, in the face of Western antagonism. Stalin's power was not unlimited, particularly in the new atomic era, and making demands he couldn't back up was self-defeating over the long run. Stalin did so anyway, that being all he knew how to do: having a hammer, he could only see nails. That Soviet aggressiveness beyond that implicit in the war with Hitler was likely to foster a strident anti-Soviet attitude in the West was either not a concern, or regarded as inevitable in any case.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Japanese had been very careful not to provoke Stalin while he fought Hitler, but with Hitler taken care of, Stalin could send the mighty Red Army east to the Manchurian border to take advantage of the weakness of the Japanese, who were clinging on desperately under terrible blows from the Americans.

The Japanese were seeking an exit from the war, but only on their own terms, vainly attempting to broker a peace via the USSR. Japanese leadership was not expecting the Soviet Union to move against Japan, even though the Kremlin had announced in April that the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact was to lapse -- slyly explaining that the end of the war in Europe meant it was superfluous, and assuring Japan that it would remain in force for another year. Japanese diplomatic staff riding the railroads through Siberia reported huge movements of Soviet troops and weapons on trains moving eastward; the reports were ignored by Japanese leadership, it seems out of desperate wishful thinking and a degree of complacency.

Stalin had planned to move in mid-August, but on 6 August 1945 the Americans dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Fearing that the war against Japan would be over before the USSR could claim spoils in the Far East, Stalin ordered the offensive to jump off immediately; it began on 9 August, the same day the Americans dropped a second atomic bomb on Nagasaki. The operation was conducted by three Red Army fronts under the overall command of Marshal Vasilevsky.

Manchuria consists of an open plain bounded by forests and mountains, aiding the defense. The terrain from the west was the most difficult, so the Japanese had focused development of lines of fortifications on the other borders of the land. Imperial Japanese Army officers tended to have a low opinion of Red Army capabilities and an inflated opinion of their own, and felt they could defeat a Soviet assault.

They were entirely wrong. The three Red Army fronts struck fast and hard, one from the west, out of Outer Mongolia, the other two from the east, from Vladivostok and Siberia. Although the Japanese Kwantung Army was depleted and short of equipment, resistance was determined, fanatical, the defenders performing suicide attacks on Soviet armor by troops strapped up with explosive charges -- nicknamed "smertniks" by Soviet troops. There was furious house-to-house fighting in the cities. The Japanese were still entirely outmatched, Red Army commanders demonstrating an astute grasp of mobile warfare that left no doubt of the outcome.

Red Army forces overran the Japanese-held southern half of Sakhalin Island and occupied the Kuriles. Stalin suggested to the Americans that the USSR cooperate in the occupation of the Japanese home islands; Truman shot back a blunt message on 18 August that such an action would be in contradiction of his understanding of the Potsdam agreements. Preparations were mounted for an invasion of Hokkaidou, but on 22 August, the day before it jumped off, Stalin ordered Vasilevsky to stand down. Koba was not inclined to confront the Americans so directly.

Japan had surrendered on 15 August, though the fighting in Manchuria lingered on to past the end of the month. The Imperial Japanese Army had been badly outmatched, but it was no walkover for Soviet troops, the Red Army suffering over 36,000 casualties, a third of them killed. The Japanese, both soldiers and civilians, suffered far worse, with hundreds of thousands of them being taken prisoner, many not being returned for years, many simply disappearing without a trace. Stalin's cancellation of the invasion of Hokkaidou was fortunate; it would have complicated Japan's surrender, and would have resulted in vast destruction.

The Americans gave the Soviets no say in the occupation of Japan -- but why should they have? The USSR, for good reasons and with effective American blessing, had avoided war with Japan to the last moment; the brunt of the war with Japan had been borne by the Americans, and the Soviets had little basis for making claims. Stalin's complaints fell on deaf ears. The Soviets exerted military influence in Manchuria, a region of Russian interest back to the days of the Tsars, and the Americans were inclined to let them have it, with little complaint.

However, the American use of the Bomb impressed on Stalin that the weapon had lived up to its fearsome potential, Koba saying the destruction of Hiroshima had "shaken the whole world -- the balance has been destroyed." Paranoid as always, he believed that the Americans had used the weapon primarily to intimidate the USSR. That was certainly a factor in its use, but its use was inevitable; exactly the same decision would have been made, even if the Soviets had not been a factor at all.

The Bomb was not an immediate concern to Stalin, since he had no intention of going to war with the Americans for the time being, and knew the Americans had no real inclination to go to war against him. It was nonetheless a major concern; on 20 August, he set up a special committee to move forward, at top priority, on development of a Soviet atomic bomb program to redress the balance. Stalin then turned his attention to the reconstruction of his country, as well as imposing his ideas of order on the population.

In September, the foreign ministers of the wartime allies met in London, the primary focus being the settlement of the postwar order in Europe. Both sides took hard lines; when Molotov made concessions, he was angrily overruled by Stalin. The conference accomplished nothing, other than to make Koba suspicious of Molotov. Once Stalin became suspicious, he was all but certain to become more so.

BACK_TO_TOP* Stalin's satisfaction with the results of the war was limited by the fact that it had left much of his kingdom in ruins. Over 2,000 towns in the Ukraine and western Russia had been damaged or all but demolished, and countless villages had been burned to the ground. Over 25 million Soviet subjects were homeless. People threw together hovels, dugouts, and shanties to provide shelter while they picked over the ruins to see what could be salvaged. Plows were drawn by women and old men.

Despite the destruction, there was some spirit of optimism among the tough Soviet people. They had survived the worst that the Fascists could throw at them. They would work and rebuild, believing that the better and freer society that Communism had been promising them for a generation was at hand. They were mistaken. State propaganda had been encouraging such delusions, but Stalin was merely waving a carrot he had no intention of actually handing out. Stalin never considered whether the people deserved to be rewarded for their sacrifices. He was only concerned that the people remained under his control, and remained free of contamination by foreign influences. The people's welfare and prosperity were secondary considerations at best.

The story of the million-plus German prisoners in Soviet custody gives a strange flavor of Stalin's thinking. The Germans were kept in their own system of camps, isolated from the Gulag that reduced millions of Soviet citizens to lives of misery. Soviet prisoners would not be exposed to foreign ideas, particularly those of a hated enemy.

Ironically, the Germans received somewhat better treatment than Soviet prisoners, though that was a very low standard of comparison. The Germans were allowed to wear their own uniforms, to write letters home, and were even bossed by their own NCOs and officers. To be sure, this last measure was also a concession to efficiency, since the German Army organization retained a formidable capability to get things done even when it was on a chain, as the Americans had found out in their own prisoner of war camps. However, there was also something of a propaganda or persuasive agenda. German officers and men went through Marxist indoctrination, and those that seemed embittered in their own cause or otherwise susceptible to the Communist message were cultivated. Once sent back home, they might be valuable resources for the USSR. Those Germans convicted of war crimes were publicly hanged. Those that survived were finally sent home beginning in 1949, though full repatriation took five years.

Soviet citizens who had been exposed to outside influences were "quarantined". There were lunacies within the lunacies. Even in Stalin's USSR, there were still some faint glimmerings of judicial process, and the NKVD received complaints from the judges about the flimsiness of charges against Soviet citizens. The NKVD was perfectly capable of fabricating much better cases, and did so. According to some Russian historians, they established fake Soviet and fake Manchurian border camps, with NKVD prisoners of Chinese origin pretending to be the staff of the fake Manchurian border camp. The NKVD's clueless victims would be taken to the fake Soviet border camp and there told they were to go into "Manchuria" and spy for the USSR. Of course, once sent out, they were immediately captured by the "Manchurians", forced to agree to work for the Nationalist Chinese, and sent back, where they were once again captured and charged with treason. Most were shot.

* Not everyone submitted to resurgent Soviet power without a struggle. The Baltic States had now changed hands again, and Stalin renewed his efforts to erase their national identities. Many of the citizens there, and in other regions where the fighting had been intense and loyalty to Stalin doubtful in the first place, had fought as partisans against one side or both sides, and were still willing to keep up the fight.

The Baltic States did not have the rugged terrain that would permit a small guerrilla force to resist a large army. NKVD troops quickly crushed resistance, hunting down guerrilla bands and throwing anyone suspected of guerrilla sympathies into the Gulag. In the western Ukraine, nationalist forces were able to fight from forest strongholds for a number of years before they were finally suppressed.

The misery was compounded when the summer of 1946 brought drought and crop failure to the Ukraine and southern Russia. The Soviet Union, a world power, could not feed its people. The peasantry who worked the land to grow the food did so as mere cogs of the state, chained to land they no longer owned by internal passports, with no ownership of their produce. Indeed, even casually plucking an ear of grain and eating its kernels could get them a sentence to the labor camps. Their lives were controlled by Stalin and the local bosses, the mini-Stalins, who gave them orders and dealt out punishments. The local bosses were responsible for living up to the quotas established in the current Party plans, and if they did not meet them, they stood a good chance of being severely punished themselves.

Through all this suffering, Stalin kept the Soviet propaganda machine running in high gear. Films praised life under the new order, and public spectacles glorified Stalin and Soviet society in his image. Voting campaigns were scrupulously carried out, even though they provided no real choices to the voters. Newsreels showed Stalin casting his vote like any good Soviet citizen, with Stalin joking a little with the cameraman. Other high Soviet officials like Molotov cast their votes in front of the cameraman, too, but few really believed it was an act of free expression. Molotov's beloved wife Polina was in the Gulag, having been arrested in 1948; Molotov himself was hanging by a thread.

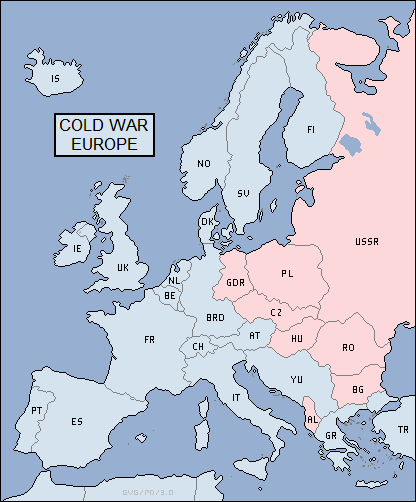

BACK_TO_TOP* In a speech on 5 March 1946 at Fulton University in Missouri, USA, Winston Churchill summed up the new reality between the Soviet Union and the West in another one of his memorable phrases: "From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an Iron Curtain has descended across the face of Europe." Stalin personally crafted a reply, published in PRAVDA, calling Churchill a "warmonger", comparing him to Hitler, saying Churchill was bent on "racist" Anglo-Saxon world domination. The Cold War had now been formally declared. Koba found it convenient, at least to the extent of justifying domestic oppression.

However, over the long term, the results could not be in the Soviet Union's favor. Only a few months later, in June, Maxim Litvinov told an American correspondent that the Kremlin had adopted an "outmoded concept" of security, based on acquisition of buffer states. In a nuclear age, what did buffer states really accomplish? If war came, they would offer no real protection; while the atomic bomb was such a ghastly and indiscriminate weapon that it made megalomaniac wars of conquest, like that of Hitler against the USSR, unthinkable. The buffer states could well be seen as a liability, not an asset. Litvinov believed, very perceptively, that the best that could be hoped for was a "prolonged armed truce".

The Americans had expected that peace would allow them to return home, disarm, and tend to their own business, as they had after World War I -- but Stalin ensured that the long custom of American isolationism was a thing of the past. The US Marshall Plan, introduced in 1947, was helping stabilize the states of Western Europe in the face of the Soviet threat.

Assistance under the Marshall Plan was even offered to the states of Eastern Europe, but Stalin had vetoed the offer, seeing it as a wedge by which the Americans would extend their economic and political influence into the Soviet sphere of influence. In that, he was obviously correct; American economic assistance unavoidably meant a stronger connection with the US economy. The US government had expected the veto, the offering amounting to a tidy propaganda exercise; had Stalin been agreeable, the Marshall Plan would have struggled to be approved in the US Congress, but by rejecting it, Stalin ensured its passage. In reaction, Koba tightened the Soviet grip over Eastern Europe.

In early 1948, Communists took over the government in Czechoslovakia. Stalin's central European concern, however, was the divided Germany. The division of the country was a contrivance, obviously unsupportable over the long run; the most straightforward solution would have been to reunify Germany as a demilitarized state, which is eventually what happened in Austria. That didn't happen, and the Soviets would maintain the division of Germany to the end.

The motives for doing so remain confusing. A reunified and demilitarized Germany outside the Soviet orbit could very well be militarized again, emerging again as a threat to the USSR. In addition, if Stalin couldn't have all of Germany, he could at least control part of it -- enhancing his control over Eastern Europe -- while working to ensure that the other was neutralized. Communist doctrine established there would be another war eventually, leading to the fall of capitalism, and then reunification could take place on Soviet terms.

In any case, it served Koba's purposes to prop up the Red East German state, even though it was unpopular with its own people and would end up a drain on Soviet resources. Large Red Army forces were stationed there to give Western Europe caution of Soviet power, as a means of balancing America's nuclear capability. The division of Germany would remain the primary focal point of the confrontation between East and West.

In June 1948, Stalin cut off access to Berlin. What precisely he expected to accomplish remains mysterious; he never tied the exercise to explicit demands. It seemed he simply thought that he could intimidate the Western powers out of the city. He thought wrong; the Americans and their allies responded with a magnificently organized airlift to keep the city supplied, presenting Stalin with the choice of either escalating the confrontation by shooting down the aircraft, or backing down. In May 1949, he decided to back down. The West had demonstrated more spine than he expected, and the airlift was a demonstration of material strength that the USSR couldn't match. The main effect of these provocations was to further reinforce American commitment to Europe, leading to the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1949.

In 1949, a civil war in Greece finally ended, with Soviet-backed Communists decisively defeated. Stalin had preferred to consolidate his holdings in Eastern Europe, and cut his losses in Greece. The civil war had also been backed by Josip Broz Tito, leader of Communist Yugoslavia; disagreement over the issue, and Stalin's attempts to pressure Tito to conform to Moscow's dictates only drove Tito away from Moscow. Koba tried to have Tito assassinated, but the clumsy attempts failed and only reinforced Yugoslav independence. The Iron Curtain had reached the limits of its extent in Europe.

* Stalin was still working hard to meet challenges from the West. On 25 September 1949 the USSR exploded their first atomic bomb, which was a close copy of the American "Fat Man" device that had smashed Nagasaki. It had been built as a top-priority project by a massive and secret project -- Operation ENORMOZ -- under the control of Beria. The USSR, lacking a good long-range bomber to deliver the bomb, had also obtained three Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers, which had been damaged in raids over Japan, with the American crews seeking refuge in Siberia. To their surprise, the crews were interned, and the aircraft were spirited off to be exactingly disassembled, reverse-engineered, and then manufactured as the Tupolev Tu-4.

The Soviets tried to keep the nuclear test a secret, but the Americans, knowing that the USSR was going to obtain the Bomb sooner or later, had been working on a nuclear weapons test detection system since 1947. An interim capability had been in operation from the spring of 1949, one aspect of which was the use of Superfortresses carrying atmospheric sampling gear to detect the radioactive traces of such explosions. Analysis of the fallout samples gave the Americans a fairly reasonable picture of the basic design of the weapon, which they codenamed "Joe One". The Americans were shocked, since they had not believed the backwards Soviets would be able to develop it so quickly. Stalin was shocked that he had been found out so fast.

The Soviet Bomb was Joseph Stalin's 70th birthday gift. His birthday was celebrated across the land, with the usual adoring speeches and the applause of audiences who clapped almost indefinitely, none wishing to be the first to stop. At the celebrations, a visitor from China, Mao Zedong, sat at Stalin's side. Two months earlier, Mao had finally evicted Nationalist Chinese forces from the mainland, and China had become a Communist state, providing a nearly simultaneous second blow to the confidence of the West. In reality, Stalin never thought much of Mao, and Soviet support of the Chinese Communists had not been enthusiastic; the Red revolution in China would prove much less of a benefit to the Soviet state than most in the West assumed.

At the celebrations, Mao and Kim Il Sung of North Korea pressed Stalin for his approval for an attack on South Korea. Stalin agreed; again, his motives remain unclear. The Americans had not made it at all clear that they considered Korea to be of strategic importance to them, and since the USSR now had the Bomb, he didn't need to fear American nuclear intimidation. Soviet pilots were covertly sent to fly MiG-15 jet fighters against American aircraft. The Americans were perfectly aware that they were fighting Soviet pilots, but were careful not to make an issue of it.

The Communists got the worst of it in the air, and the Americans reacted with surprising strength and determination on the ground after initial bungling. Stalin claimed in conversations that he wanted to tie the Americans down in Korea, but that may have been little more than a rationalization. If it wasn't, the ploy backfired, with the US performing a rapid defense buildup, correcting the decline of America's armed forces following the end of World War II. In addition, Stalin could not have been entirely pleased to see that Mao's People's Liberation Army had fought the Americans to a standstill, making Mao much more of a potential threat to the Soviet Union.

The war in Korea settled down into a stalemate, a drain on both sides, both sides negotiating to put an end to it -- the major complication in the talks being the fact that the Americans, remember the fate of the Hiwis, refused to repatriate prisoners against their will -- while conducting limited offensives to reinforce their bargaining positions. Whatever Stalin's true motives in Korea, the war there had become a sideshow for both sides.

Stalin escalated his propaganda war with the West, charging Western leadership with tyranny and claiming that the Soviet Union carried the banner of democratic freedoms -- Stalin having his own notions of democracy. With his other face, he lashed out at Voroshilov, Molotov, and Mikoyan at a dinner, calling them British spies. A hush fell across the room.

Khrushchev claimed in his memoirs that late in the war, Stalin had started to become "not quite right in the head." Since Stalin clearly had never been quite right in the head by any civilized standard, the implication that he had become worse was terrifying. The overwhelming pressures of war had forced reality on Stalin for a time, but when Soviet victory became certain, he began to slip back into his brutal delusions at an accelerating pace. He was getting old and was not healthy-looking, his mindset becoming increasingly suspicious and arbitrary. In 1951, he mentioned, idly as if nobody in particular was around: "I'm finished, I trust no one, not even myself."

The scientists and artists went through the motions of praise for the Great Leader, but that did not save them from denunciation. Beria and Zdahnov began the witch hunt against the intelligentsia, locking up famous poets, singers, and movie stars. Another witch hunt was begun against the medical profession, particularly against the Jewish doctors who served the Kremlin. The eminent specialist Vinogradof and others were arrested, and forced to sign phony confessions that they had plotted to poison members of the government.

Even in a land where people's concepts of truth had been so totally corrupted, nobody believed it. What they believed, with plenty of justification, that a new wave of major purges was brewing that might exceed the brutality and madness of those of the 1930s. The Jews were apparently being lined up as the primary victims; they were non-Russian and had too many contacts abroad. Stalin had already largely driven them out of the party and the government apparatus, and now it seemed Koba found Hitler's attempt at a "final solution" of the "Jewish problem" appealing. Of course, the purge wouldn't stop at Jews. Everyone, no matter what their rank or ethnic background, was terrified.

* On 1 March 1953, Stalin failed to emerge from his apartment, and that evening the guards finally built up the courage to break in. They found him lying on a sofa, conscious but unable to speak. He appeared to have suffered a stroke. Beria and other officials arrived on 2 March, with Beria making dire threats against the doctors who were trying to tend to the fallen Stalin, but there was nothing the doctors could do. In fact, it is strongly suspected that Beria delayed obtaining care for as long as possible, though no doubt the threat to the doctors was still perfectly sincere.

Stalin's son Vasily and daughter Svetlana also came on 2 March. They had not been close to their father for some time. Both had unsettled personal lives, jumping from one broken relationship to the next. Vasily was nothing like his half-brother Yakov; Vasily was an alcoholic who had been promoted to major general of the Red Air Force by officers who feared annoying Stalin, though there was no evidence Stalin paid much attention to Vasily one way or another. Svetlana had hardly seen her father since 1943, when one of her lovers, who had the bad luck to be Jewish and so a target of suspicion by the antisemitic Stalin, had been arrested and thrown into the Gulag. She had protested to her father, who flew into a rage and slapped her twice. When she did see Stalin after that, she was a wreck for days afterward.

Vasily was characteristically drunk when he came to visit his stricken parent, raising a fuss and accusing the doctors of trying to kill his father, and was finally told to leave. Vasily would soon find himself dismissed from his high position, struggling along as a nonperson under a new name, until he died in 1962 at age 41.

Svetlana stayed with her father. Stalin lingered for three more days, finally dying on 5 March 1953. Towards the end, his breathing became more labored and increasingly difficult, and he turned blue as he slowly choked to death. Svetlana recorded his last acts, saying "he opened his eyes and cast a glance over everyone in the room. It was a terrible glance, insane or perhaps angry, and full of fear of death."

Then "he suddenly lifted up his left hand as though he were pointing to something up above and bringing down a curse on all. The gesture was incomprehensible and full of menace." He stilled and in time stopped breathing. Beria would seem in line to succeed him in the power struggle that followed, but he was then arrested and shot. He had terrorized too many people and made too many enemies. The generals had a score to settle with him, and not only did Zhukov lead the party that arrested Beria after luring him out from under his security umbrella, but a Soviet general pulled the trigger that ended his sordid career.

Khrushchev took Beria's place and would begin denunciations of Stalin, trying to reform the clumsy and ugly structure Stalin had created, if with very mixed results. Khrushchev could never decide if he was coming or going, having been a party to the terror in Stalin's time, then repudiating it after Stalin was gone; condemning Stalin's ways, while still remaining in awe of him; attempting to mend fences with the West, but resorting to bluster and threats in preference to diplomacy; trying to liberalize, and then reflexively cracking down when things threatened to go out of control.

That was later. Hearing of Stalin's death, many citizens wept. Of all the monstrosities of Stalin's life, the most appalling was that state propaganda had convinced the people who he had misled, in every sense of the word, sadistically terrorized, tortured, and murdered, to love him. One Soviet citizen later said that when Stalin talked on the radio, it was "like listening to the voice of God." A woman recounted how after hearing the news of Stalin's death, she asked her fiance: "How are we going to live? It's impossible without him!"

Not everybody had been taken in. Her fiance replied: "Peacefully." She commented later: "He was smarter than I was." Even in death, Stalin proved malevolent, with the crowds lining the streets of Moscow for his funeral becoming so packed that about a hundred people died in the crush. He would cast a long shadow after that. The days of lunatic mass terror quickly ended, but the state would remain authoritarian, xenophobic, fossilized, and inefficient, gradually running out of steam until it finally ground to a halt and fell apart into a rusty heap of scrap almost forty years later.

BACK_TO_TOP* This document began as a set of notes taken from a historical documentary series named RUSSIA'S WAR: BLOOD UPON THE SNOW, shown on the US PBS television broadcasting network in the late 1990s. The series was directed by Viktor Lisakovitch, and detailed the reign of Joseph Stalin and in particular his war with Hitler.

This series was very good, but really just provided a basic skeleton to be filled out from print sources. The second pass on the document was based on readings from the relevant volumes of the extensive TIME-LIFE series on World War II. The following sources contributed to the final pass:

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 apr 06 / gvg v1.0.1 / 01 mar 08 / Review & polish. v1.2.0 / 01 feb 10 / Added more on Allied coalition politics. v1.2.1 / 01 dec 11 / Review & polish. v1.3.0 / 01 jan 14 / More on conferences, Soviet-Japanese relations. v1.4.0 / 01 dec 15 / Stalin's postwar rule. v1.4.1 / 01 nov 17 / Review & polish. v1.4.2 / 01 oct 19 / Review & polish. v1.4.3 / 01 sep 21 / Review & polish. v1.4.4 / 01 aug 23 / Review & polish. v1.4.5 / 01 aug 25 / Review & polish.BACK_TO_TOP