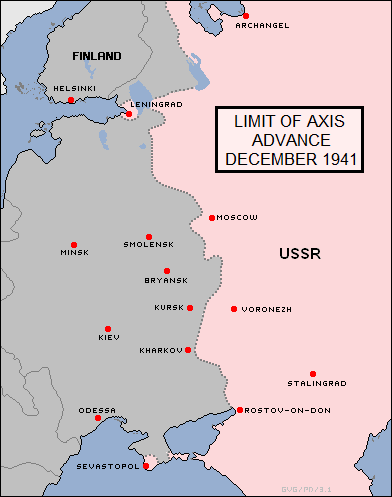

* Hitler had never planned on a long campaign in the USSR, having believed he could quickly knock the Soviets out of the war. That wasn't what happened; as the fighting continued into the fall of 1941, Wehrmacht forces were finding themselves falling behind schedule and confronted with mounting difficulties, particularly since the Germans lacked winter gear. Despite the difficulties, the Nazis performed a drive on Moscow, codenamed Operation TYPHOON -- but by December 1941, the offensive had run out of steam, and the Red Army struck back hard, throwing the Wehrmacht back from the gates of Moscow. Only a few days after the offensive jumped off, the Japanese bombed the US Navy fleet at anchor in Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, bringing America fully into the war.

* Although the Germans put siege to Leningrad, they did not attempt to capture the city, Hitler having decided against it. The city had been isolated, and Hilhe felt there was no reason to waste his troops. Leningrad could be pounded into rubble with shelling and bombing, and left to starve; it would fall into his hands in time. Hitler would then wipe it from the face of the earth, and turn the land over to the Finns.

Having successfully secured his flanks, and in particular emboldened by the tremendous German victory at Kiev, Hitler now ordered Army Group North's panzers to be redirected to renew the drive on Moscow. In late September, Zhukov received reports that German tanks were being loaded up on railway flatcars and shunted in the direction of Moscow. He thought this was a deception exercise at first, but within days Red Army troops in front of Moscow were reporting the arrival of German armor from the north.

As with Leningrad, Hitler wanted Moscow completely destroyed, erased from history. On its site, he planned to create an artificial lake. The final drive on Moscow, codenamed Operation TYPHOON, began on 2 October 1941, after Wehrmacht efforts in the north and south had wound down. Guderian's panzers shifted north from their excursion into Ukraine, and made rapid progress at first. Hitler wanted to encircle Moscow and bag all the Red forces defending it. The German offensive ran along a huge front 640 kilometers (400 miles) wide. The attack was conducted by 14 panzer divisions and 74 infantry divisions, totaling 1.8 million German soldiers. The Red Army could field 800,000 men in 83 divisions to defend Moscow, but only 25 of these divisions were fully effective, and the Soviets were desperately short of aircraft and armor.

General Ivan Konev was commander of the Red Army's West Front and had to face the onslaught. By 7 October, the Germans were beginning encirclements of Soviet Western Front and Reserve Front concentrations in the region. The Germans took 660,000 prisoners at Vyazma, for a total loss of three million men since the beginning of the campaign. A German general wrote with satisfaction: "Each night the villages went on burning, coloring the low clouds with blood-red light."

Stalin had once again created a disaster by refusing to let Red Army units withdraw and escape capture. Now that things had become desperate, he was finally more willing to listen to his generals. He called Georgiy Zhukov, still in charge of the defense of Leningrad, to come to the Kremlin on 5 October. Zhukov left his aide Ivan Fedyuminsky in charge in Leningrad, and flew to Moscow on 7 October. Stalin briefed him on the situation and ordered Zhukov to go to West Front Headquarters to sort things out.

The next day, Zhukov reported to Stalin that there was nothing standing in the way of the Germans and Moscow. The situation was very serious. The only positive news, if it could be called that, was that the Germans were still preoccupied with the destruction of Soviet troops they had encircled at Vyazma.

On 10 October, Stalin ordered Zhukov to take command of the combined fronts and relieve Konev. Stalin said that Konev would be handed over to a revolutionary tribunal, which meant almost certainly that he would be shot as a scapegoat. Zhukov wrote later that he replied bluntly: "Pavlov was shot, but that changed nothing. The situation at the front didn't improve. Therefore, I don't recommend you to do the same to Konev. He is an immensely experienced and clever man, strong willed and capable of establishing order. I request that you appoint him as my deputy."

The request was granted. Zhukov now focused on the immediate problem of saving Moscow. He had only about 90,000 men, all that was left of 800,000 that had been available before the beginning of TYPHOON. Zhukov mobilized the citizens of Moscow to build defenses. He formed citizens' militias from students, older men, and disabled men. They would be sent into combat with little training, to be thrown under the tracks of the German drive. Many would die.

On 13 October, the Germans broke through the final major Soviet defense line in front of Moscow. On 14 October, the Germans were at Podolsk, 48 kilometers (30 miles) from Moscow. A unit of officer cadets, many only teenagers, managed to slow them down for a few vital hours. All the cadets were killed. On 16 October, the Soviet diplomatic corps in Moscow abandoned the capital to head for Kubyshev on the Volga, 640 kilometers (400 miles) to the east. Although Stalin had a bunker built in Kubyshev, after receiving assurances from Zhukov that the city could be held, Koba decided to not leave Moscow. He undoubtedly could not tolerate the humiliation of being chased out of town.

However, the flight of the bureaucrats led to panic among the citizenry. Police authority had all but disintegrated, there was looting, and the railway stations were clogged with civilians. The panic died down when the radio announced on 18 October that Stalin was still in the capital, and on 20 October Stalin imposed martial law. Troublemakers, or for that matter anyone who didn't do as ordered promptly or dared to talk back, would of course be shot on the spot.

On the front to the west, the soldiers continued to fight stubbornly. On the road to Moscow, General Pavilov performed a valiant last stand, and 28 of his men stopped 50 German tanks. Pavilov had been informed by Zhukov that he would be shot if he let the Germans through.

Near the end of October, Stalin paid a tentative visit to the front. His armored car bogged down in the mud about halfway there, and as it was getting dark, he decided he'd seen enough and took another car back to Moscow. Despite this faint-hearted effort, after his pathetic collapse at the beginning of the invasion, he was now demonstrating an admirable resolve -- as well as his customary ruthlessness. In late October, he asked a city military commander what the plans were for the annual military parades to celebrate the anniversary of the revolution. The officer was astounded that Stalin would consider a parade when it seemed that Moscow would soon fall to the Germans, and raised objections: "But what if the Germans break through and bomb the parade, Comrade Stalin?"

Stalin replied: "Clear away the dead and wounded, and continue with the parade."

The night before the parade, Stalin addressed the Soviet people from a subway station to rally them once more to the cause. He poured contempt on Hitler's belief that the Slavs were "untermenschen", born slaves, replying: "And it is these people without honor or conscience, these people with the morality of animals, who have the effrontery to call for the extermination of the Great Russian Nation -- the nation of Plekhanov and Lenin, of Belinsky and Chernyshevsky, of Pushkin and Tolstoy, of Gorky and Chekhov, of Glinka and Tchaikovsky."

The German invasion was not merely an injury -- it was an insult, an expression of contempt for the peoples of the Soviet Union. Stalin proclaimed: "If they want a war of extermination, they shall have one!" The defiant tone of the speech went over well in Britain and the United States.

The parade went ahead the next day, 7 November. Fighter squadrons were on alert to deal with any Luftwaffe intruders that might attack the parade, and medical emergency teams were standing by to deal with any casualties. Fortunately, it snowed that day, and the parade went forward without the slightest hindrance from the Germans. The news sent to the world of the parade was, in itself, an expression of defiance against the Germans.

Stalin spoke to the troops, expressing his conviction that the Germans were strained to the utmost and would quickly collapse. Although the event was to commemorate the Revolution, he called out to the troops by invoking the great heroes of Russia's imperial past. Socialism wasn't enough to motivate people to fight. Stalin had to appeal to their patriotism. Some of the soldiers in the audience were not so convinced, but that didn't matter. They were immediately marched off to the front lines to fight.

* In the meantime, the German advance had been slowing as the weather continued to get nastier. The Germans were now trying to drive their tanks forward through snow, sleet, and mud, on primitive roads. Hitler's forces were at the end of a very long and tenuous supply line in steadily worsening weather, and had little equipment for or training in winter fighting. Guderian had requisitioned winter clothing in October, only to be reprimanded. Soon winter clothing would be sent forward through the supply network, but it remained stockpiled in depots in the rear: the primitive supply network was overloaded, and ammunition took priority.

On 31 October, the German high command had to order a pause to the advance, which was moving at a snail's pace anyway. The Soviets used the pause to rebuild their forces with astonishing speed, but the pause was short-lived. The weather turned to ice and snow, making the ground solid enough to permit movement of tanks, and on 15 November the Germans moved forward again, with pincers driving north and south to encircle Moscow and deal the Red Army the final killing blow. However, Guderian's panzer group, moving up from the southwest, found itself blocked by stubborn Soviet resistance. On 27 November, the Red Army made a limited counterstroke against Guderian's forces in a well-organized and well-equipped attack, halting Guderian's drive on the city.

The German effort to circle the north of Moscow had better luck. On 2 December, German advance units reached Krasnaya Polyana, 21 kilometers (17 miles) from the center of Moscow, finally being blocked by antitank obstacles built by the citizens of Moscow. The Germans were now in a position to shell the city with long-range artillery.

On the evening of 2 December, General Rokossovsky received a call on the "special line" from Stalin. The situation was "very difficult", as Rokossovsky recollected after the war, and it was unlikely that Comrade Stalin was calling to have a pleasant chat. Rokossovsky picked up the phone "with some trepidation." Stalin asked him directly: "Are you aware, Comrade Commander, that the enemy has occupied Krasnaya Polyana, and are you aware that if Krasnaya Polyana is occupied, it means that the Germans can bombard any point in the city of Moscow?"

At dawn, the Russians counterattacked the Germans at Krasnaya Polyana and drove them out. The Germans left behind a pair of 300-millimeter heavy guns that they had been setting up to begin shelling the city.

Stalin was in fact doing a great deal of micro-managing, at one point ordering Zhukov and other senior officers to personally go and evict the Germans from a small village named Dedovo. The brass showed up, much to the astonishment of the officers on the line, and sent in a tank along with a company of infantry to drive out a platoon of Germans. The whole thing was entirely silly, but Zhukov admitted later: "Stalin must be given his due. By his harsh and unscrupulous attitude, he was able to achieve the well-nigh impossible."

Stalin was greatly helped by the weather. December brought blizzards and depths of cold few Germans were familiar with. Weapons froze up and men suffered from frostbite and disease, adding to the hundreds of thousands of German soldiers on the casualty lists. The Luftwaffe found itself grounded in the severe weather, but the Red Air Force seemed to only increase its activities. Although the Fuehrer demanded that the drive on Moscow be continued, as winter tightened its grip, commanders in the front line were acknowledging reality and setting up for the defensive.

Runstedt's forces had seized Rostov in the south on 19 November in a driving snowstorm, but his troops were overextended, and counterattacks by Timoshenko's troops forced the Germans to withdraw. Hitler was angry at Runstedt for pulling out, the Fuehrer never having seen any of his troops in a major retreat before. Runstedt submitted his resignation on 30 November and Hitler accepted it the next day, 1 December -- though the Fuehrer tried to soften the action by announcing his removal from command as a "sick leave", and giving him a birthday gift of 250,000 marks a few weeks later.

Runstedt's replacement was Field Marshal Walter von Reichenau -- previously commander of the 6th Army, a macho bulldog of a man with a perpetually furious expression who the aristocratic Runstedt found crude and overbearing. Command of the 6th Army went to Reichenau's chief of staff, Friedrich Paulus. Hitler thought that Reichenau would turn things around, but Reichenau almost immediately reported that the situation was impossible, and that the withdrawal had to continue.

The Fuehrer, agitated, flew to Poltava in Ukraine on 3 December to find out what was going on. He was quickly told by General Sepp Dietrich that the decision to withdraw had been correct. Dietrich was commander of the Leibstandarte Division of the Waffen SS -- the combat arm of the Nazi Party SS organization, which was under Wehrmacht operational control, though the SS was personally loyal to Hitler -- and was a longtime hardcore Nazi. Hitler had a high opinion of him, and to find that even Dietrich believed retreat had been necessary was something of a shock. The Fuehrer's composure was going to be further shaken over the next few weeks.

BACK_TO_TOP* To the north, Hitler ordered the German Army and the Luftwaffe to pound Leningrad to rubble, rather than send German troops to be ground up in the Soviet defenses. The Nazis bombarded the city relentlessly.

As the northern weather went cold and icy, Leningrad began to slowly die. Less than half the food needed to keep the citizenry alive was coming in. In mid-October, the authorities conducted a check of citizen's ration cards and tightened up control of the rationing. A woman who worked at a printing shop that produced ration cards was found with a hundred ration cards in her possession. She was summarily shot.

The citizens had no fuel. They burned all their possessions to stay warm. By late November, food rations had shrunk to what would prove to be an all-time low. A citizen received a handful of bread that tasted of sawdust. People ate paste, shoes, birds, mice, soups made from stinging nettles, anything they could find. Household pets disappeared quickly, their masters weeping as they killed the animals and then ate them.

The city had been flooded with refugees when the Germans closed in on it, and many had no papers. No papers meant no ration card. The refugees started starving in their camps outside the city as early as September, and all in the camps would eventually die. By the onset of winter, people were dropping in the streets, their frozen bodies left unattended until the authorities picked them up at intervals and dumped them into mass graves all over the city. Eventually, the lack of manpower to dig graves forced the authorities to begin cremating the bodies.

Although Soviet authorities kept it a secret for decades, some of the citizens turned to cannibalism, and a few of them murdered to obtain bodies when corpses were not conveniently available. Soldiers coming back from the front heard stories of some of their fellows being killed and eaten; they began to travel in armed groups. The authorities recorded about 1,500 cannibals. Most were women who were trying to save their children.

The Soviets had been able to sneak some supplies across Lake Ladoga to the east, with the material delivered by train to a railhead at Tikhvin and then shuttled over the lake by barge in the dark. The Germans seized Tikhvin on 9 November, shutting down the last direct connection between the city and the outside world.

In late November, the ice on Lake Ladoga became thick enough to support sleds and then trucks, but without a railhead to the lake, there was no way to supply the trucks with adequate loads of food. The Red Army recaptured Tikhvin on 9 December, as part of a general offensive of which more is said later, but of course the Germans thoroughly wrecked everything when they left. It most of the rest of the month to get the railroad back in working order. Supplies wouldn't start to flow until January, and it would take several months to bring them up to subsistence level.

In the meantime, the citizens continued to starve and die. Defiantly, the people went on with their lives as best they could. Historians performed their studies, architects designed new structures, and composer Dmitri Shostakovich wrote the LENINGRAD SYMPHONY. The symphony was performed in the city, with musicians recalled from the front to play. The conductor was faced with difficult rehearsals, as musicians died of starvation every day. A quarter of a century later, the first night performance was reenacted by the survivors of the orchestra and the audience. Musical instruments were placed in the empty chairs of the dead of the symphony.

Even children made their own contribution to this great and appalling story. A young girl, Tania Savicheva, kept a diary to record life and death under the siege, listing calamities in a simple fashion: "Grandmother died, 25 January 1942, at 3:00 PM." Following pages listed death after death, and concluded: "The Savichevas have died. All died. Only Tania is left." The girl was evacuated, but was too malnourished to survive. Her diary was read by Soviet prosecutors at the Nurenburg trials of Nazi leaders after the war.

Leningrad would suffer siege for 900 days in all, but the first winter was the worst. It wasn't until March that the supply line was fully operational. The boats brought in food and took out noncombatants, dealing with Luftwaffe attacks as best they could. A pipeline and power line were laid across Lake Ladoga to keep the city working. Survivors planted crops anyplace there was to plant them, and by the summer rations wouldn't be a particular problem, partly because the number of mouths to feed had been drastically reduced. Nobody knows exactly how many people died in that hideous winter in Leningrad, but estimates are on the order of two million.

BACK_TO_TOP* As the Germans pushed through the snow towards Moscow in early December, the Soviets were preparing a counterstroke. Red agent Richard Sorge at the German embassy in Tokyo provided intelligence that the Japanese were not preparing to attack the Soviet Union from Manchukuo. Sorge had reported German preparations for BARBAROSSA back in June and had been ignored, but now Stalin believed him. Stalin withdrew more than half of the USSR's combat strength from Siberia, shuttling 40 divisions west to deal with the Nazis. These divisions were well trained, experienced, well equipped, and their officer corps had not been badly injured by the purges. They had a thousand tanks and a thousand aircraft. They had already given Guderian a taste of what they were capable of on 27 November; now they were ready to be used in earnest.

There were half a million men available for the assault. On 5 December the Red Army launched limited counteroffensives against German positions, and found that the Germans surprisingly gave up their positions easily. Encouraged, the Soviets decided to push harder. Rokossovsky's forces to the southwest of the city and Konev's in the north led the push. The front was almost a thousand kilometers (600 miles) wide. The Soviets were now committing massive reserves that German intelligence had never really accounted for; Red artillery had plenty of ammunition and was close to supply bases; and the Red Air Force was out in strength.

Indeed, although the Red Air Force had lost immense numbers of planes in the early days of the war, most of the planes destroyed were obsolescent anyway, and since the aircraft had been mostly shot up and bombed while sitting on airfields, losses of trained pilots had been comparatively light. The Red Air Force was now beginning to obtain quantities of modern aircraft, notably the formidable, heavily-armored Ilyushin Il-2 Shturmovik close-support aircraft, or "Flying Tank". The Soviets were well able to operate these aircraft in otherwise intolerable winter weather. For example, ground crews would drain all the oil from an aircraft when it landed, and keep the oil heated with a field stove until it was poured back in to ready the aircraft for combat again.

The Soviet T-34 tank, better than anything the Germans had and designed with winter operations as a consideration, was now becoming available in quantity. Some Red Army officers were demonstrating what could be done with the T-34, inflicting painful losses on German panzers in stand-up fights. The new "Katyusha (Sweet Little Katy)" barrage rocket launcher was capable of pouring a wall of explosive on German positions with munitions whose shrill screams shattered the nerve of those who survived the attacks. Well-trained Soviet ski troops moved quickly through German positions. Within 48 hours, the Soviet juggernaut was in full motion.

The Red Army drove forward from Moscow in the center and attacked to open a lifeline to Leningrad in the north, while Soviet forces pushed towards Kursk in Ukraine. Hitler ordered Army Group Center to stand its ground, but it was impossible. On 20 December, Heinz Guderian told Hitler that his troops could no longer fight. The Soviet Union had seemed on the edge of defeat, and instead had inflicted an undeniable defeat on the Germans.

Soviet propaganda paraded pictures of German soldiers captured wearing women's winter coats or other ridiculous gear, calling them "Winter Fritzes". Films showed the numb and frightened faces of German prisoners, herded off to prison camps. Most would not return. There were no great numbers of German prisoners; although the German Army had taken a beating, there were few more professional armies in the world, and the Germans had managed to fall back in order to avoid encirclement. However, Hitler was not happy with commanders that gave ground, and sacked dozens of generals. Runstedt had been one of the first to be given the boot, with those following prominently including Guderian, who would never hold a major field command again. Von Brauchitsch suffered a heart attack and was forced to retire on 19 December, with the Fuehrer having little kindly to say about him and then assigning himself, Hitler, the role of Commander in Chief of the German Army.

Some historians have claimed that Hitler's insistence on standing fast kept the German Army from collapsing in the face of the Red Army's offensive, while others have suggested that it only increased suffering and losses, since the Soviet drive would have run out of steam as it outstretched its supply lines anyway. Hitler might well have considered the lesson that Stalin had shown such trouble grasping -- that it was better to abandon terrain of no great value in itself to preserve forces that could be used later to give the enemy a real blow under much more favorable conditions. Whatever the reality of the situation, Hitler believed that his stubbornness had saved the day, and came to an unambiguous conclusion that would have major consequences later: Hold ground at all costs.

* The Germans had been forced to abandon piles of equipment. The Soviets proudly displayed these discards to British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden when he arrived on a diplomatic visit on the evening of 15 December. The British and the United States had doubted the Soviet Union would survive, and the Soviets displayed the results of their victory with great pride. Eden was properly impressed, in fact seeming to become somewhat overly taken with Stalin, though when Stalin proposed to Eden that the British recognize the Soviet seizure of the Baltics and eastern Poland -- even suggesting that after the war, the British could balance these appropriations by taking over bits of France and the Low Countries with Soviet acceptance -- Koba found the British distinctly cool to the idea.

Eden wired Churchill from the British embassy to report on Stalin's proposals, with the prime minister replying that "we are bound to the United States not to enter into secret and special pacts." Churchill saw no sense in a pointed rejection of Soviet territorial ambitions, however, telling Eden that such questions would have to wait on "the peace conference when we had won the war." Stalin did not like that answer at all, and pressed Eden on the matter.

* In the newly-liberated territories, Russian soldiers were greeted ecstatically by liberated villagers, and Muscovites celebrated Christmas and New Years' with exuberance that had bubbled up through the gloom. Still, as Red troops moved into territories held by the Nazis, they were appalled by the destruction and desolation. The Germans wrecked everything with their characteristic efficiency as they withdrew, and their rule over the occupied lands had not been gentle in the first place.

The Nazis took particular pleasure in defacing the treasures of Slavic culture. In the town of Klim, they burned the house of the composer Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky, and destroyed the score of his Sixth Symphony. Count Leo Tolstoy's house in Yasnaya Polyana was razed to the chimneys, and his gravesite was dug up to allow German soldiers to be buried there instead. Russian Orthodox churches were often burned and their icons destroyed.

The churches were also often sites of executions. The Germans killed Soviet civilians with little provocation or hesitation. Soviet propaganda films caught the savagery with heart-wrenching vividness, showing the corpses of the hanged swinging in rows in the falling snow; the burned bodies of victims in shattered houses; a mother weeping, arranging the hair of her dead daughter, a pretty young woman killed by the Nazis.

BACK_TO_TOP* In the meantime, the United States had come into the war in full force. On 7 December, Maxim Litvinov arrived in Washington DC as the ambassador to the USA, replacing the obnoxious Oumansky. Even as Litvinov was arriving at the airport, the news was flying around like a cyclone that Japan had just attacked the US Navy base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, inflicting massive damage. There was the difficulty that the Japanese attack did not give Roosevelt an option for declaring war on Germany, but Hitler then conveniently declared war on the USA on 11 December. Some claim the Fuehrer made a great mistake in taking on America, but the USA was already backing the war of the British and Soviets against the Reich, while clearly building up forces to intervene directly; Hitler had cause for taking the fight to the Americans when they were at a disadvantage, instead of waiting and fighting them under poorer circumstances.

America was now a full combatant in the conflict. The full entry of the US into the war was of enormous significance, but it was not entirely good news for the Kremlin in the short term, since it meant a reduction of American military aid for the USSR. On the other side of the coin, the Japanese had committed themselves to a fight with the Americans, and it was out of the question that they would present a threat to the Soviet Union in the meantime. Indeed, given the massive imbalance of power between Japan and the USA, over the long run Japan might well be permanently eliminated as a threat.

On 22 December, Churchill arrived in Washington DC along with British government and military staff to discuss war planning. It seemed appropriate at the time to produce a statement of common purpose for those at war with the Axis. The statement was released on 1 January 1942, with the signatories including the USA, Britain, the USSR, and all the other co-belligerents from China down to Albania, described simply as the "United Nations". The term was used because Roosevelt was cautious about calling it an "alliance", which had legal implications that might have caused problems with the US Congress, but the concept of the "United Nations" had been born and would take on greater importance in the future. In any case, the document stated:

QUOTE:

Being convinced that complete victory over their enemies is essential to defend life, liberty, independence and religious freedom, and to preserve human rights and justice in their own lands as well as in other lands, and that they are now engaged in a common struggle against savage and brutal forces seeking to subjugate the world, DECLARE:

1: Each Government pledges itself to employ its full resources, military or economic, against those members of the Tripartite Pact and its adherents with which such government is at war.

2: Each Government pledges itself to cooperate with the Governments signatory hereto and not to make a separate armistice or peace with the enemies.

END_QUOTE

In hindsight, though it was an obvious declaration under the circumstances, it seemed more than slightly ironic that the Soviet Union would sign a document proclaiming its commitment to "human rights and justice". Indeed, Ambassador Litvinov had balked at the reference to "religious freedom", and only caved in after Roosevelt gave him a heavy sales job -- the president knew that Soviet hostility to religion didn't go over well with American voters, and wanted at least a symbolic gesture to reassure the electorate. It was actually no great issue to Stalin; he was perfectly comfortable with symbolic gestures. Implementation, of course, was another matter, and Roosevelt didn't greatly concern himself with it.

BACK_TO_TOP