* At the beginning of the Second World War, the experience of the First World War gave most of the combatants the expectation that CW would be used to an even greater extent. Newspaper articles and popular fiction predicted that poison gases would turn entire regions of Europe into lifeless wastelands. To almost everyone's surprise, it didn't happen. A fragile stalemate kept poison gas out of action during World War II. The use of CW also remained restrained in the postwar period, though the balance between attempts at control and the pressure towards their use became increasingly unstable.

* As the war turned against Nazi Germany and Allied bombers pounded German cities to rubble, the incentive to use CW increased. By 1944, the Nazis had enough tabun to kill everyone in London, as well as large stockpiles of more traditional chemical agents. They did not use them, not even at Normandy, where the Allied invasion forces were almost completely defenseless against gas attack. Partly this appears to be due to the fact that having been gassed himself, Hitler had some distaste for gas. More significantly, there was a peculiar complementary misunderstanding between the two sides.

British intelligence proved much more competent in World War II than its German counterpart, but German security concerning nerve gases was very tight, and the Allies did not know such weapons existed. Rumors and sketchy intelligence concerning nerve gases were lost in the noise of the war.

On the other hand, German researchers knew that papers on organophosphate toxins had been published in the international scientific press for decades, and so there was good reason to believe the Allies had nerve gases of their own. This belief was reinforced by the fact that all mention of organophosphate toxins had disappeared from the American scientific press at the start of the war. The Germans assumed it was due to military censorship. That assumption was right as far as it went, but the organophosphate toxin the Americans were trying to de-emphasize was the insecticide "DDT", which had been developed in Switzerland just before the war and was strategically important, particularly for military operations in malarial tropical regions.

The principle British researcher on organophosphate toxins, Bernard Saunders, did discover a nerve gas, known as "diisopropylfluorophosphate (DFP)", but it was much less deadly than tabun or sarin. However, DFP could be mixed with mustard agent, forming a combination that was nastier and also had a much lower freezing point than mustard by itself, creating an effective winter-weather agent.

In any case, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill made it very clear to Hitler that if Britain were attacked with poison gas, the British would saturate German cities with gas in retaliation. The Allied strategic bombing force was much stronger than Germany's; the Allies were gaining air superiority over Germany; and Hitler had every reason to believe that if he used nerve gases on Britain, the Allies would strike back ten times as hard. Both the Germans and the British believed they held parity in gas warfare, and neither Churchill nor Hitler realized that Germany had the upper hand.

* In fact, Churchill himself almost gave away the game. Although Britain had signed and ratified the Geneva Protocol, he had little squeamishness over poison gases: to Churchill, they were just another weapon. During World War I, he had been so enthusiastic about gas warfare that his wife Clementine had jokingly called him the "Mustard Gas Fiend". During the desperate days of 1940, when Britain was facing a German invasion, Churchill had energetically built up an arsenal of chemical weapons to greet German troops landing on England's shores. Even after the threat of invasion faded away, the British continued heavy production of chemical weapons.

In the summer of 1944, the Germans began firing their V-1 flying bombs, small jet-propelled missiles armed with conventional warheads, at London. The guidance system of the flying bombs was very crude, and they came down almost anywhere. Most of those killed and injured were civilians who just had the bad luck to be where a flying bomb happened to fall. Churchill was enraged at the blatantly indiscriminate nature of the attacks and wanted to retaliate by plastering German cities with gas bombs.

Churchill's outrage was understandable, given the deaths and injuries of British civilians, but a little illogical. The British Royal Air Force's Bomber Command had been pounding German cities in generally indiscriminate night raids for several years. The V-1 flying bomb, and the V-2 ballistic missile that followed the V-1 in the fall of 1944, were frightening and destructive, but their effect did not compare to the devastation heavily dealt out to German civilians by Allied thousand-bomber raids.

While Churchill was very strongly in favor of performing gas raids, British military planning staffs investigated, and recommended against it. Their objections were not on grounds of humanity, but simply because the relatively crude gases available to the British would have required so many bomber payloads to have been effective that the conventional bombs then in use could do more damage. Churchill reluctantly gave up the idea.

Incidentally, the Germans had actually designed chemical warheads for the V-1, but it is unclear if such a weapon could have been put to effective use. Tabun of course is hideously toxic, but it is also volatile, and large concentrations of it are needed to be really effective. Such concentrations would have been difficult to achieve with the V-1, since they could not be launched fast enough to provide a heavy bombardment, and they fell all over the city at scattered, near-random locations anyway. Mustard gas, being persistent, would have been a bigger nuisance, but high explosive was arguably more destructive, intimidating, and effective.

As the Allies closed in from west and east, Germany's position became increasingly desperate. The pressure on the Germans to use anything they could to fight back increased tremendously, but even under those conditions they did not use gas on the Allies. Use of gas might have gained the Germans a short-term advantage, but the overwhelming retaliation that Hitler had every reason to expect would likely only have accelerated defeat.

* The United States was the "arsenal of democracy", in President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's phrase, and American war production included chemical weapons, in large quantities. In fact, even before the US formally entered the war, the Americans were discreetly shipping phosgene to the British.

Once war was formally declared, the US Army's CWS received massive new funding, reaching a billion USD in 1942. Huge new production facilities were built, most notably at Pine Bluff Arsenal in Arkansas and the Rocky Mountain Arsenal near Denver, Colorado. The CWS also opened a huge test range in Utah, named the "Dugway Proving Ground", where there was plenty of space to test chemical and biological weapons on duplicates of German and Japanese buildings.

The US had never ratified the Geneva Protocols, but President Roosevelt considered poison gas a barbarous weapon. He had no intention of authorizing its use, much to the disappointment of the CWS. The American chemical weapons program only thrived because of fear of Japanese CW efforts. Newspapers often printed reports of Japanese use of CW against the Chinese, and Roosevelt issued stiff public warnings that if the Axis used poison gas on American troops, they could expect massive retaliation in kind.

As noted earlier, the Japanese did apparently use CW in China before the outbreak of war in the Pacific, but the newspaper reports that appeared in America during the war are hard to take at face value. Chinese Nationalist Chiang Kai-Shek wanted to encourage the Americans to continue to provide military assistance to the Nationalists, and stories of atrocities were an encouragement. Claiming the Japanese used gas to win battles also helped excuse Nationalist defeats.

* With so much gas stockpiled, accidents were likely to happen. On 2 December 1943, the merchantman SS JOHN HARVEY was waiting its turn to be unloaded at the harbor of Bari in southern Italy. Unknown to almost everyone, JOHN HARVEY was carrying 2,000 45-kilogram (100-pound) bombs full of mustard gas. Even most of the JOHN HARVEY's crew did not know about the gas bombs.

A few days earlier, the Allied high command announced they had obtained complete air superiority over southern Italy. They hadn't informed the Luftwaffe, and that evening a hundred Ju 88 bombers swept in to raise hell for 20 minutes. The German raid was a stunning success, a little Pearl Harbor: they sank 17 ships, badly damaged 8 more, killed a thousand men, and injured 800. Gas bombs on the JOHN HARVEY ruptured, and as the ship sank a layer of mustard gas and oil spread over the harbor, while mustard gas fumes swept ashore in a billowing cloud. Many civilians died during the raid and later.

The officers in charge of the gas bomb shipment on the JOHN HARVEY had been killed while they frantically tried to scuttle the vessel, and nobody else knew about the gas bombs. Sailors were taken ashore to a hospital, where they were wrapped in blankets and given tea. The next morning, 630 of them were blind and developing hideous chemical burns; within two weeks, 70 of them died. The crew of a British escort vessel picked up survivors during the raid and escaped to sea. During the night almost the entire crew went blind, and many developed burns. The vessel managed to limp into Taranto harbor with great difficulty.

At first, the Allied high command tried to conceal the disaster, since the evidence that gas was being shipped into Italy might convince the Germans that the Allies were preparing to use gas, and provoke the Germans into pre-emptively using gas themselves. However, there were far too many witnesses to keep such a secret, and in February the US Chiefs of Staff issued a statement admitting to the accident, emphasizing that the US had no intention of using gas except in retaliation against Axis gas attacks.

* The Japanese never used CW on American troops, and so the Americans never used CW on the Japanese. In fact, the Japanese had given up development and production of chemical weapons in 1941. Their stockpiles of poison gas were puny compared to the mountain of agents that the Americans had produced, which exceeded by a comfortable margin all the gas used by all sides in WW1.

Information on Soviet gas warfare development during WW2 and after is sketchy. The Soviets presumably manufactured their own substantial stockpiles of chemical weapons, but if so, they kept it a tight secret. One thing is known. When the Soviets advanced on the Nazi nerve gas plant at Dyenfurth in August 1944, large quantities of liquid nerve agents were poured into the Oder and the factory was set up for demolition, but the Red Army got there before the charges could be set off. The Dyenfurth plant was dismantled and carted off to Russia to begin production for Soviet dictator Josef Stalin, instead of Hitler. The Soviets now had the secret of tabun, sarin -- and a new, even deadlier nerve gas named "soman" that the Germans had discovered a few months earlier, but had not yet brought into production.

In April 1945, the British captured a German ammunition dump that contained 105-millimeter shells marked with a single green ring and the legend "GA". They were filled with tabun. Other dumps were found, with a total of about a half-million shells and 100,000 aerial bombs filled with nerve gas. The British and Americans also interrogated captured German chemists, most of them having fled west to avoid capture by the Soviets. The discovery that the Allies had been almost completely ignorant of the existence of nerve gas was a shock to Allied intelligence and leadership.

* The failure of any combatant to make serious use of CW weapons in World War 2 remains puzzling. All the major combatants had large stocks of chemical weapons, and some of the chemical agents available in quantity were much nastier than those used in World War I. Most believed that CW would be used, and most had incentives to use it at one time or another. Reluctance to use such weapons out of distaste for them or fear of retaliation in kind played a part, but it seems likely that the deciding factor was that circumstances were never quite right to push any of the combatants over the threshold. In hindsight, it seems to have been a very near thing.

BACK_TO_TOP* After the war, a large proportion of the chemical weapons stockpiled during the war were loaded onto old ships, taken out to the deep sea, and scuttled. The disposal of such large quantities of chemical weapons was widely publicized.

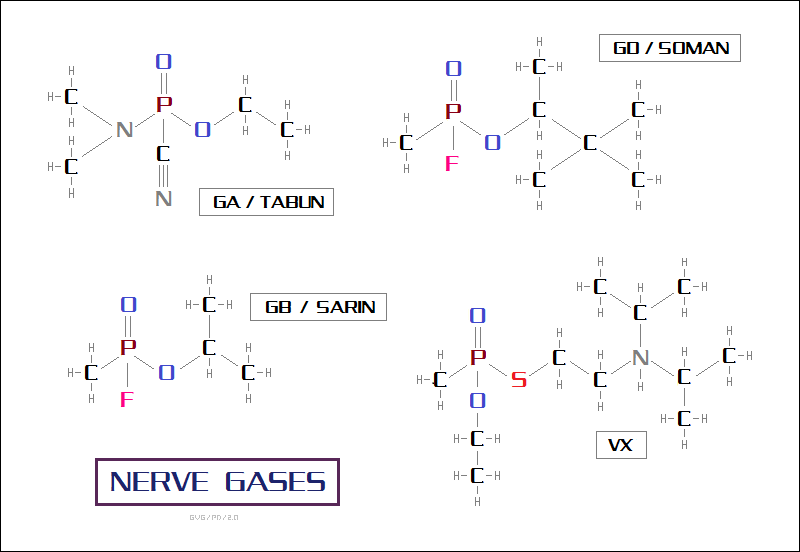

The Cold War was beginning, however, and secret research and development into the new nerve gases became a high priority on both sides of the Iron Curtain. The nerve gases became generally known by their German code designations: "GA" for tabun, "GB" for sarin, and "GD" for soman, with the "G" handily providing a reminder of their German origin. The Americans, British, and Canadians formed a three-member alliance called the "Tripartite Agreement" to investigate and develop techniques of warfare with the new "G agents". The Australians joined this alliance in 1965.

The British performed a series of experiments, mostly focusing on GB / sarin, through the late 1940s and into the 1950s. They never went into full production of nerve gases, though they did construct an experimental pilot plant. The British had historical reasons for disliking gas weapons, and besides, the war had exhausted Britain's financial resources.

The Americans had no such obstacles. Although there had been a major drawdown of the US military just after World War II, within a few years the Soviet threat led to another buildup. Intelligence that the Soviets had picked up German nerve gas technology and manufacturing facilities led the US to ramp up production of chemical agents again, focusing on GB / sarin.

In 1953, the US Army "Chemical Corps", as the CWS had been renamed, built a plant in Alabama to manufacture the proper chemical precursor, and then completed production at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal. The Dugway Proving Ground in Utah, which had been shut down after the war, was reopened in 1950 and expanded for renewed chemical and biological weapon tests.

* By the early 1960s, the US had a huge arsenal of chemical weapons, and in fact had begun production of a new poison gas. In 1952, in an odd echo of Schrader's discovery of tabun, Dr. Ranajit Ghosh of Britain's Imperial Chemical Industries discovered a new and deadly nerve agent while performing research into pesticides. The chemical was too dangerous to use as a pesticide, so Ghosh passed it on to the British government.

The British had already committed to pilot production of GA / tabun and GB / sarin and did not need a new agent, so they handed it on in turn to the Americans. As mentioned, the British never went into full production of nerve gases, and finally renounced use of offensive CW in 1956. The Americans developed the formula into a weapon, designated "VX". The older G agents were volatile and tended to evaporate rapidly. They were not persistent. VX, in contrast, had the viscosity of motor oil, and like mustard gas would puddle up on the ground after an attack and stay there. VX was persistent and much more toxic than GB / sarin. The US opened a plant in Newport, Indiana, to produce VX in volume. By 1967, the Americans had thousands of tonnes of VX. A range of other "V agents" were developed, with the "V" providing a handy reminder of their viscous nature, but VX was the most popular and prominent.

Other work was performed on delivery systems, including artillery shells, the M23 gas landmine, the M55 unguided gas rocket, and the Mark 116 "Weteye" air-dropped gas bomb. Defensive systems were not ignored either, with development of new gas masks, protective clothing, decontamination systems and kits, and primitive detection systems. A nerve gas antidote, known as "atropine", was also evaluated, and atropine hypodermic auto-injector kits were produced in quantity. Atropine is an anti-spasmodic drug, a derivative of the natural toxin belladonna obtained from the nightshade plant. Incidentally, ophthalmologists often use atropine to dilate the pupils of patients, to permit inspection of the interior of their eyes.

* The Americans also investigated gases based on hallucinogens. In 1943, a researcher named Dr. Albert Hoffman at the Sandoz drug firm in Switzerland was investigating drugs derived from ergot, a fungus that infects wheat, when he spontaneously went into wild hallucinations. Hoffman had accidentally discovered the hallucinogenic drug "LSD".

In the postwar period, the Chemical Corps wondered if hallucinogens might make effective "humane" weapons that would not kill enemy soldiers, simply eliminate their will to fight -- or, as it might have been put in the somewhat later era when hallucinogens became recreational drugs, persuade them to "make love not war". During the mid-1950s, experiments were conducted on volunteers, as well as unwitting patients in psychiatric institutions, with mind-altering drugs.

The results of these tests were encouraging, but LSD itself was not appropriate for military use. It was much too expensive to synthesize in volume, and was not a very good aerosol. The Army finally found a substance named "BZ" that was cheap and could be dispersed in clouds over the battlefield. BZ, nicknamed "Agent Buzz" for obvious reasons, was also chemically related to belladonna. It made its victims somewhat ill, causing them to vomit or stagger around. They might later suffer memory lapses and hallucinations. During one test, according to a story, a soldier under the influence of BZ offered a second soldier who was just as intoxicated an imaginary cigarette. The second soldier turned him down, saying it was the last in the pack. Effects could persist for up to two weeks.

BZ was produced in pilot quantities, but then the Army had second thoughts. It was too toxic, and an enemy soldier on hallucinogens was just as likely to do suicidally crazy and dangerous things as become happy and agreeable, and the Army didn't want to use such an unpredictable agent. BZ was discarded.

The concept of BZ poses an obvious question: why didn't the Army develop a nonlethal agent that simply put enemy soldiers to sleep? In fact, the idea of "knockout" gases has been around a long time, but it's not as easy as it sounds. A gas could be made of opiates or some class of tranquilizer, but there would be no way to administer such a gas in a controlled fashion, leading to overdoses and fatalities, particularly in small children and people in weak health. Exactly what work was done by the US Army on knockout gases is unclear; what is apparent is that the Army never obtained them in any quantity.

Incidentally, the Soviets did deploy knockout gases, a fact that came to light in 2002. On 23 October of that year, a band of Chechen terrorists seized a Moscow theater, taking over 800 people hostage. On 26 October Russian security forces, believing that the terrorists were about to start killing the hostages, pumped knockout gas into the theater's ventilation system. The security forces were able to regain control of the theater from the terrorists, but at least 115 of the hostages were killed by the gas. Some observers speculated that the gas might have been aerosolized Valium or even BZ, but the Russians were very tight-lipped about the nature of the agent.

* The US military did actually use "less lethal" chemical agents in Vietnam. In World War 2, the British and Americans had cooperated on powerful herbicides in their chemical weapons development programs, and devised spray systems and cluster bombs that could be potentially used with devastating effect against an adversary's croplands. Such weapons were not used against the Axis, but after the war the British used a herbicide developed by the Americans, known as "245T", during their war against Communist insurgents in Malaya in the late 1940s and the early 1950s. The British sprayed 245T onto areas where they thought insurgents might be growing food or hiding under jungle cover.

In the early 1960s, as the US became more involved in Southeast Asia and jungle warfare, the Americans considered the British experience in Malaya and decided to resurrect it in a big way. From late 1961, C-123 Provider cargo planes were fitted with tanks and spray gear and sent to South Vietnam to conduct defoliation flights -- either RANCH HAND missions, intended to deprive the Viet Cong (Vietnamese Communist, or simply VC) guerrillas of jungle cover, or TRAIL DUST missions, to destroy crops the VC needed to stay fed.

The Americans came up with six different herbicides for use in South Vietnam, designated Agents "Green", "Pink", "Purple", "White", "Blue", and "Orange" in accordance with the color code painted on the drums of chemicals. The defoliant exercise proved successful, and ramped up into a massive chemical warfare operation against plants over much of Southeast Asia. Sprayer units proudly displayed the slogan: ONLY WE CAN PREVENT FORESTS -- a parody of the popular US Forest Service poster slogan: ONLY YOU CAN PREVENT FOREST FIRES.

The most potent of the herbicides was Agent Orange, which consisted of a mix of 245T and small quantities of dioxin, a substance with some toxicity to humans. Agent Orange was used on the densest areas of forest, and caused vegetation to grow wildly until it died and rotted. So much herbicide was used in Vietnam that in 1968 there was a shortage of household weedkillers in the United States. The heavy use of Agent Orange was tentatively linked to birth defects in the Vietnamese population, and maladies such as cancers among troops exposed to the chemical. Agent Orange would become a major cause of dispute between the US government and Vietnam veterans after the war.

The Americans also used CS powder in combat. In 1965, the Americans began using CS to flush VC guerrillas out of their hiding holes in the ground, and eventually employed it in large quantities. The Americans were accused of conducting chemical warfare from the use of herbicides and CS, and a legalistic argument followed. The critics conceded that the chemicals used were not in the same league as traditional poison gases, much less with nerve gases, but pointed out that use of such nonlethal toxins was a step that could quickly escalate towards the use of nastier poisons and established a dangerous precedent. In fact, rumors persisted that the Americans evaluated lethal chemical weapons in combat during the Vietnam War, but no honest evidence was ever found to back up such claims.

* The controversy over the American use of nonlethal chemical weapons in Vietnam helped keep the fact that the US had large stockpiles of lethal chemical weapons in the international spotlight. The US government found their stockpiles of chemical weapons an embarrassment. World opinion was solidly against chemical weapons and there was no way the Americans could use poison gases, except in retaliation. The US had the nuclear deterrent, making the need for lethal chemical weapons arguable.

There was also a frightening incident that raised public fears. On 13 March 1968, an F-4 Phantom strike aircraft flew a test mission over the Dugway Proving Ground with chemical dispensers containing VX. One of the dispensers wasn't completely emptied during the test, and as the F-4 gained altitude after its bombing run, VX trickled out in a trail behind the aircraft to drift into Skull Valley, north of the proving ground, and settle over a huge flock of sheep. 6,000 sheep were killed, and the incident provoked national attention at a time of high public political unrest and suspicion of the government. In the summer of 1969, a leaky VX munition stored at a US military installation on Okinawa sent 23 servicemen to the hospital. The Japanese government had not even known chemical weapons were being stockpiled on Japanese soil.

In 1970, US President Richard M. Nixon announced a moratorium on the development and production of new chemical weapons, though work on defensive measures continued. This was a step in the right direction, if not an outright ban. The United States also belatedly ratified the 1925 Geneva Protocol in 1975, and the next year began discussions with the USSR on additional measures to limit chemical weapons. However, chemical weapons showed no sign of dying out.

BACK_TO_TOP* While Soviet secrecy kept the details hidden, the USSR engaged in a chemical arms buildup that almost certainly matched that of the Americans. The Soviets seemed to have a particular liking for GD / soman; they were believed to have stolen the formula for VX, and developed a variant that remained effective in extreme cold. It was clear the Red Army possessed a strong CW capability.

Egyptian forces were strongly suspected to have used CW, possibly supplied by the Soviets, during their intervention in Yemen in the 1960s. In the mid-1970s reports began to trickle out of Southeast Asia that the Vietnamese, another Soviet ally, were using a new and savagely effective gas in attacks on Hmong tribesmen in Laos, who had been allies of the Americans and stubborn foes of the Communists. Refugees spoke of aircraft pouring out a "yellow rain" that caused choking, chemical burns, massive bleeding, and rapid death. There were many reports, but the puzzling thing about the combination of symptoms reported was that it matched the action of no known chemical agent. US Army scientists suspected that the "yellow rain" was some mix of chemical agents, or a new chemical or biological toxin.

The idea that "yellow rain" was some biological toxin was given a little weight in 1981, when a leaf and a few other plant fragments that were covered with a white mold were examined. The mold had a very high concentration of fungal poisons known as "mycotoxins". However, the Soviets and Vietnamese denied they were using chemical or biological warfare in Laos. The evidence was thin at best, and the mycotoxins discovered, while deadly, were nowhere near as toxic as any nerve gas and would have been much more expensive to produce. In the absence of any definitive information, "yellow rain" never amounted to anything more than an unsettling rumor.

* In the meantime, talks with the Soviets on chemical weapons limitation had bogged down over issues of verification and enforcement. CW hawks in the US, suspicious that the USSR was using the talks as a mask for improving their CW capability, challenged Nixon's moratorium on the development and production of new chemical weapons.

The environmental and safety concerns that had in good part led to the moratorium were an obstacle to the production of new chemical weapons, but the hawks had a solution: "binary nerve gas". Back in the 1950s, the US Navy had been concerned about the problem of storing nerve gases on board ships, and had investigated a concept where the safety of a nerve gas munition could be improved by splitting it into two separate chemical "charges".

The US did build a 155-millimeter artillery shell to delivery binary nerve gas, in the form of GB / sarin. The shell contained two chambers, one with contained methylphosphonic difluoride, better known as "difluor (DF)", and another containing simple isopropyl alcohol. When the shell was fired, the barrier between the two chambers broke, and the rapid spin of the shell mixed the two precursors to form the gas, which was dispersed when the munition burst.

VX could also be produced from binary precursors consisting of a substance known as "VC" and sulfur. VC was actually almost the complete VX molecule, and was apparently fairly toxic and nasty in itself. The US Defense Department developed a plan for fielding binary nerve gas weapons, but even with suspicion of Soviet intentions and actions the US Congress showed no inclination to fund the program.

* The suspicions continued to grow. The USSR intervened in the civil war in Afghanistan late in 1979, and reports from Afghan mujahedin guerrillas indicated that the USSR was using CW. However, although the mujahedin spoke of "nerve gas", they described clouds of colored smoke and choking symptoms that sounded more like those caused by asphyxiants. As mentioned in the previous chapter, nerve gases are generally odorless, colorless, and cause convulsions and suffocation. The reports were never confirmed. It seems plausible that the Soviets did use riot agents in Afghanistan, and riot agents can be lethal in high concentrations. The reports from Afghanistan, as well as the "yellow rain" stories from Laos provided little honest evidence of any serious Soviet use of lethal CW.

By that time, however, the Soviets were not the only issue. There was widespread suspicion that smaller states with militant and authoritarian regimes were developing chemical and biological weapons as a military equalizer. That became absolutely clear after the beginning of the Iran-Iraq war in 1980. The Iraqis, badly outnumbered by the Iranians during the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s, resorted to CW. They manufactured mustard gas; lewisite; and nerve agents, including GA / tabun, GB / sarin, and VX. They developed a "dusty mustard" that consisted of the liquid agent absorbed by a talcum-like powder, which made it easier to disperse as an aerosol and more concentrated in its effects.

The Iraqis used mustard gas and GA / tabun to spearhead attacks on Iranian forces. Poison gas appears to have been a contributing factor to the eventual defeat of Iran in 1988. It is believed the Iranians took the lesson to heart and built up their own arsenal of chemical weapons after the war. After the conflict with Iran was over, Iraq's Saddam Hussein used his chemical weapons to deal with rebellious Iraqi Kurds who had been assisted by the Iranians. The Iraqis used mustard gases, possibly combined with nerve gases, against the Kurdish town of Halabjah in March 1988, killing thousands of people.

Incidentally, this attack became a subject of controversy in 2003, when the US government was planning to invade Iraq, and held up the attack on Halabjah as evidence of the criminal nature of the Iraqi regime. Critics responded that a US government intelligence report released a few years after the attack had actually identified the Iranians as the culprits, that they had dosed the town heavily with hydrogen cyanide in a ghastly "friendly fire" accident.

However, closer examination showed the claim to be highly inconsistent with the facts and evidence. The critics also claimed that the US had helped create the Iraqi CW program, but this claim was based merely on the fact that in 1988 Dow Chemical had sold a large batch of insecticides to Iraq that might be used as precursors for chemical agents. Evidence was uncovered much later that the Iraqi poison gas program was created with help from the Egyptians, a finding that also helped confirm that Egypt had or has a highly active chemical weapons program. Of course, Egypt being an American ally, the US was not inclined to probe too deeply into that matter.

* In any case, during the Gulf War in 1991, there were widespread fears that Saddam Hussein would use his chemical and biological weapons on Coalition forces. The US military was not well-prepared to deal with CB warfare, and it was a wake-up call. The military used the TV news media to show to the public, and of course to Saddam Hussein, that US troops were well-prepared and well-equipped for such attacks, but it was somewhat an exercise in deception; the military was behind the learning curve and scrambling to catch up.

There were particular fears that the Iraqis would attack Israeli cities with "Scud" intermediate-range missiles, armed with GB / sarin warheads. The Israeli government issued their citizens protective gear, including gas masks for adults, a hood that covered the head and chest of small children, and plastic boxes for infants. US President George HW Bush made loud public threats that any Iraqi use of chemical and biological weapons would be met with massive retaliation. The nuclear option was not stated as a possible response -- but it wasn't ruled out either.

For whatever reasons, Saddam Hussein did not use any of his weapons of mass destruction. After the defeat of Iraqi forces, UN inspection teams destroyed many of Iraq's chemical and biological weapons stockpiles, but doubts remained that all those stockpiles had been found. Those doubts would have major consequences.

The US armed services decided to take CW more seriously, with military training taking CW into account and the military acquired appropriate gear. Hand-held and vehicle-mounted chemical agent detection instruments have been obtained, and there's been development of "hyperspectral imaging (HSI)" sensors for aerial platforms like drones with a range of capabilities, including the remote detection of chemical agents. HSI sensors have demonstrated some ability to give advance warning of chemical weapon attacks, though such sensors have so far found it difficult to distinguish dangerous biological agents from, say, airborne pollen. Artificial intelligence technology promises to make them "smarter" and more effective, better able to distinguish the signatures of chemical agents.

Research is being conducted on better medical countermeasures against nerve agents. Modern biochemistry has determined that nerve agents kill by binding to "acetylcholinesterase (AChE)" -- an enzyme that breaks down the neurotransmitter "acetylcholine" after it binds to nerve synapses. AChE is extremely efficient: one AChE molecule can break down 600,000 acetylcholine molecules per minute. Without functioning AChE, the synapse can't "reset" after being activated, disabling it.

Nerve agents disable AChE by binding into AChe's active center, a narrow slot, and then cannot be dislodged. Neurons coming to a halt, victims quickly go into convulsions and then stop breathing. Soldiers now carry anticonvulsants to deal with the convulsions, and atropine to try to deal with the nerve agent itself. Atropine, however, leaves much to be desired, since it doesn't really fix the problem. Nerve gases allow synapses to be jammed up with acetylcholine; instead of getting rid of the acetylcholine buildup, atropine simply blocks the acetylcholine receptors in the synapse, meaning the acetylcholine doesn't do anything any more. Nerve agents still disable AChE, and it can take weeks after exposure to regenerate the stock of AChE.

Drugs called "oximes" can pry the nerve agent out of the slot in AChE, but oximes have traditionally had a limitation, in that they don't get through the blood-brain barrier -- excluding them from the mass of neurons that make up the brain -- while nerve agents can. New oximes have been developed that can get through the blood-brain barrier. However, although these improved oximes can deal with sarin, soman is much faster-acting, and by the time treatment is needed, it's too late.

There has been talk of developing vaccines to defend against nerve agents. Humans can build up an immunity to some, not all, toxins by slowly increasing dosage of them, with the immune system generating antibodies that match the toxins and neutralize them. Progress along this line of research has been slow. A related scheme, experimentally demonstrated in mice, uses genetically modified adenoviruses to modify liver cells so they will generate enzymes that tear apart nerve agent molecules.

* While Saddam Hussein put poison gas back on the list of operational military weapons, the collapse of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s and early 1990s did lead to a major step forward in controlling chemical weapons. The Russian Federation that emerged from the collapse of the USSR had no money to pursue chemical weapons development, and the chemical weapons stockpiles on its territory were a dangerous environmental liability. Under such conditions, the Russians and Americans came to an agreement in 1992 to destroy their chemical weapons stockpiles.

Putting this commitment into action proved difficult for the Americans. The traditional means of disposing of chemical weapons was to put them on old cargo ships, take the ships out to the deep sea, and sink them. This practice was continued into the 1950s, with ships sunk everywhere from the Baltic to the Pacific, but with the rise of environmental consciousness by the 1960s, scuttling had become completely unacceptable. In fact, a number of fishermen were injured every year while trawling in waters where chemical weapons had been discarded, when they came into contact with crusted clots of mustard agent that were stuck in their nets. With the end of ocean dumping, the number of such incidents declined in the 1970s and faded out.

The US built a specialized incinerator on Johnston Atoll in the middle of the Pacific as a pilot plant to demonstrate the safe destruction of chemical munitions. More incinerators, or other types of neutralization facilities, were to be built at all of the chemical weapons storage sites in the continental US for local incineration of the 33,000 tonnes (36,300 tons) of agents stockpiled, since transportation of the agents for destruction elsewhere was ruled out.

The plan, however necessary, proved troublesome. Many of the chemical weapons were becoming leaky and dangerous to store or transport. Opposition from local groups and environmental organizations such as Greenpeace complicated government disposal plans. Initial cost estimates for the disposal of American chemical weapons were in the billions of dollars, and proceeded to double, while schedules slipped out.

The Russians, who did not have anywhere near the resources of the Americans, were confronted with an even nastier problem. The Americans have provided funds to help with the Russian disposal effort. The hidden costs of chemical weapons continue to mount. When the Japanese pulled out of Manchuria at the end of World War II, they left behind chemical weapons stockpiles that remained intact, if increasingly rusty and leaky, 50 years later. The Japanese government spent huge sums to build an incineration facility and dispose of the ancient munitions.

* Despite the difficulty of the task, it was done, with the last declared abandoned chemical weapons stockpiles finally disposed of in the summer of 2023. Of course, it is generally believed that many nations still maintain active stockpiles of chemical weapons. The issue resurfaced in the course of the Syrian civil war when, on 21 August 2013, a number of sarin-laden rockets were fired into Ghouta, in the Damascus metropolitan area -- with hundreds, possibly thousands killed. United Nations inspectors verified that nerve gases had been used in Ghouta.

US President Barack Obama had publicly stated that use of chemical weapons by the Syrian government would be "crossing a line", and the US would respond. The result, however, was finger-pointing as to who was responsible: while the Syrian government was the obvious suspect, the attack was also labeled a "false flag" operation conducted by rebels to push outside intervention in the civil war on the rebel side. Given that the breakdown of Syrian society had led to government weapons stockpiles falling into rebel hands, it was not out of the question that the attack had been performed by rebel forces.

The denials of the Syrian government were not given much credence, but the Obama Administration was reluctant to take military action against the Syrian government while the US was fighting against Islamic State insurgents that were among the rebel groups in the civil war. Obama also checked on the level of support for military action in his administration and Congress, to find it negligible. The Obama Administration chose a diplomatic response, working with Russia to pressure the Syrian government to get rid of its chemical weapons stockpiles.

The Syrian government agreed to allow an international team to eliminate the government's chemical-weapons stockpiles, with the exercise completed in 2014. The result was the destruction of 1,300 tonnes (1,430 tons) of weapons and precursor chemicals plus 1,200 munitions, and the demolition of 27 production facilities. US Secretary of State John Kerry declared: "With respect to Syria, we struck a deal where we got 100% of the chemical weapons out."

The Obama Administration was later strongly criticized for warning of military action and not following it up -- but the threat of military action proved enough to push a diplomatic solution, and Obama always regarded military action as a last resort. Indeed, military action couldn't have been as thorough in destroying Syria's chemical weapons stockpiles.

Not everybody involved in the disarmament effort was certain that all of the chemical weapons had been disposed of. There were later reports of use of chlorine gas weapons, but since they could be made so easily from industrial chemicals and were relatively ineffective, few protests were made. However, on 4 April 2017, Syrian military aircraft hit the town of Khan Sheikun in northern Syria with a handful of left-over chemical weapons loaded with sarin gas, killing scores of civilians.

US President Donald Trump replied with a strike on the Sharyat air base in central Syria on 6 April, which was hit by 59 cruise missiles. There was no follow-up to the strike; it was simply intended to tell the Syrian government not to use sarin or other highly lethal chemical agents again. It didn't happen again -- whether because of deterrence or exhaustion of chemical weapons is impossible to say.

BACK_TO_TOP