* The fall of the Confederacy left Union leadership with the awkward problem of how the nation would be "reconstructed". Obviously, there could be no return to the prewar status quo, but what should the new order be like? President Andrew Johnson and the Radical Republicans in Congress had different ideas of what should be done, leading to a clash between the president and Congress. In the end, Congress prevailed, passing a number of measures intended to restore the Union on a more just basis.

* With the end of the war, most of the Union soldiers were given mustering-out pay, then sent home at Federal expense. Southern soldiers had to make their way home as best as they could, begging what little food was available from people who were not well-off themselves. Many of the veterans were disabled, missing eyes or arms or legs, making their situation even more difficult. Large regions of the South had been shattered and impoverished by the war. A New England journalist named Sidney Andrews visited the South some months after the end of the fighting, and described Charleston, South Carolina, in one of his reports: "A city of ruins, of desolation, of vacant houses, of widowed women, of rotting wharves, of deserted warehouses, of weed-wild gardens, of miles of grass-grown streets, of acres of pitiful and voiceful barrenness."

Columbia, South Carolina, burned by Sherman's army, was even more appalling: "It is now a wilderness of ruins. Its heart is but a mass of blackened chimneys and crumbling walls." Another visitor from the North surveyed the path that Sherman had left while passing through the state: "Many miles like a broad black streak of ruin and desolation -- the fences all gone; lonesome smoke stacks, surrounded by dark heaps of ashes and cinders, marking the spots where human habitations had stood."

The South had expended all its financial resources in the war. Southern citizens who had invested in Confederate central and state government bonds lost all their money. The liberation of slaves resulted in an enormous loss of capital. Plantations and farms lay idle, roads and bridges were in disrepair or ruined, factories were burned and gutted, and the rail system, not particularly robust to begin with, had been almost completely destroyed.

Yankee soldiers liked to heat up rails using a bonfire of ties, then wrap the rails around trees to make sure they couldn't be simply spiked back into place -- these mementos of the conflict being known as "Sherman bowties". Even the cotton crop had been expropriated by the Federals. One hotel-keeper said of the Yankees: "They've left me with one inestimable privilege, to hate 'em. I git up at half-past four in the morning and sit up 'till twelve at night to hate 'em."

The most immediate problem was simple starvation. The Federal government, although lacking a comprehensive plan for rebuilding the South, took some measures to help the destitute Southerners. In March 1865, the US Congress had established the Freedman's Bureau, led by Union General Oliver Howard, to assist the liberated slaves through supply of provisions, teaching them to read and write, providing assistance in court, re-uniting families scattered by the war, and even conducting marriages -- slave marriages having had no legal standing.

The Freedman's Bureau was also empowered to help whites who had sworn loyalty to the United States, and so between 1865 and 1870 the bureau distributed over 21 million rations, with a quarter of them going to starving white people. This act of sensible compassion was appreciated by Southerners not too far gone in their resentment. One wrote: "There is much in this that takes away the bitter sting ... Even crippled Confederate soldiers have their sacks filled and are fed."

Another saving grace was that though the Federal military occupation of the South was humiliating and oppressive to Southerners, as mentioned there were no widespread reprisals against Confederate officials. In fact, to an extent, there was a revival of Southern patriotism to the Union. In the spring of 1868, a Wisconsin farmer named Gilbert H. Bates, who had been a Union sergeant, walked through the South from Vicksburg to Richmond, wearing his Union Army uniform and carrying the Stars and Stripes, in an effort to confirm Southern loyalty.

It is hard to know how much to make of such a stunt, but Bates, who was unarmed and carried neither food nor money, reported that he was treated kindly and warmly, given lodging and sustenance, even when he walked over routes where Sherman's army had left destruction in its path. In fact, when he arrived at Richmond, he was greeted with the cheers of crowds and salutes of cannon. There were many Southerners who believed their struggle for independence had been noble, but who had come to realize that secession hadn't been a good idea, and that the South was better off without slavery.

Sergeant Bates' walk through the South was in modern terms a "feel-good exercise". It is hard to find fault with it in itself, but it only went so deep. Even at the time of his walk, the South was in the painful processes of readmission to the Union, and determining its new social and racial order. Neither of these processes were characterized by much in the way of shining ideals.

BACK_TO_TOP* Reconstruction lasted twelve years. The US Constitution, having said nothing in specific about secession, of course said nothing in specific about Reconstruction of states that had seceded -- and so, it was effectively anybody's educated guess of how to go about it. Lincoln had wanted to streamline the re-admission of the South to the Union, seeing no necessity in asking much more than for Southern citizens to swear loyalty to the Union and ban slavery. Now he was dead; the Radicals in Congress felt that Lincoln's approach was much too lenient, and preferred a more punitive approach.

There was not only the problem of what to do with the rebels, but of what to do with the slaves who had been freed by the war. The question of civil rights for the freed blacks was politically tricky. Free blacks did not have civil rights in most "free" states of the Union. Only Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, Wisconsin, and Rhode Island even gave black men the unrestricted right to vote. In 1867, Connecticut, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, and Ohio considered full suffrage for blacks, and all rejected it.

Many in positions of power did not feel that indiscriminately giving the vote to illiterate ex-slaves was wise, but many of the Radical Republicans in Congress believed in Negro suffrage as a matter of principle, and as a means of strengthening the Republican hold on the South. There was also the issue of land redistribution. General Sherman had issued an order late in the war to hand land on islands along the coast of the Carolinas to freed slaves -- the order being summarized as "forty acres and a mule" -- but the government had not confirmed the titles to the land parceled out to the black folk. Conservatives disliked the concept of land redistribution; moderates were uncertain; Radical Republicans were all for it -- though some tempered the action by suggesting that the Federal government buy up lands, instead of simply seizing them. In sum, circumstances were such that no policy could please everybody.

Exactly what would Abraham Lincoln would have accomplished had he lived to complete his second term in office is an unanswerable question that has been endlessly discussed. The Radical Republicans hadn't liked his ideas on Reconstruction, and he would have been forced to compromise in many ways, but Lincoln was a shrewd card player; the odds were that he would have got more than his half a loaf out of it. Lincoln was also an astute visionary, and though he placed his ideology in the background and was willing to trim to the winds of practicality, he did have strong ideals and a desire to put them into practice.

There is no way of knowing what would have really happened, that being an alternate history that came to a dead end the instant John Wilkes Booth pulled the trigger on his derringer -- but it seems hard to believe that it wouldn't have turned out better than it did under Johnson, a person who hardly knew the meaning of the word "compromise".

Johnson was an extremely strong-willed man. He had been born poor, working his way up, teaching himself to read, setting up a successful business as a tailor, and then moving into politics. He was a Democrat who stayed with the Union when his state left it, and when the state was returned to the Union by force he was its military governor for three years, a target for widespread hatred. He was hard-minded and charmless; pictures of him generally show him with a scowl on his face.

However, Johnson's real problem was not his lack of charisma, but his lack of ideas. He had been brought onto the Lincoln presidential ticket in 1864 in order to bring in votes from loyalist Democrats, and in many ways his instincts ran crossways to those of Lincoln. Johnson was a solid State's Rights man, a person who believed in the Constitution with the conviction of a Biblical literalist, and a white supremacist who believed that free blacks should be kept in their place. Johnson was narrow-minded, arrogant, incapable of forging a consensus or seeing an alternate point of view -- a builder of moats, not bridges. In some ways, everyone would have been better off if he hadn't been so courageous.

Incidentally, Johnson's enemies like to paint him as an alcoholic. For all his faults, he wasn't; he had been ill when he was sworn in as vice-president, took a shot of whiskey to fortify himself, and ended up taking the oath of office in a clearly inebriated state. From that time on, he was mocked as "the drunken tailor".

* In the summer of 1865, while Congress was out of session, Johnson implemented his Reconstruction plan. He recognized the legitimacy of the state governments of Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana, which Lincoln had recognized, as well as that of Virginia. In the seven other states still not readmitted to the Union, amnesty was to be given to anyone who signed the loyalty oath, with some exceptions. Once an adequate number of loyal voters had been registered, the state would then stage a convention. The convention would nullify the state's ordnance of secession, abolish slavery, and repudiate Confederate and state war debts.

Given little choice, the governments of the ex-Confederate states mostly chose to ratify the 13th Amendment -- Georgia becoming the 27th state to ratify, on 6 December 1865. Over three-quarters of the states having given their assent, the 13th Amendment was law, and slavery was formally ended. It seemed something like extortion to make ratification a requirement for the readmission of these states to the Union, but these were extraordinary times. Ratification, after all, could be seen as establishing the sincerity of the ex-Confederate states in returning to the Union, slavery having taken them out of the Union in the first place.

The 13th Amendment was not only significant in banning slavery; it was also significant in that Congress trampled all over the sacred cow of States' Rights. Three ex-Confederate states did add "interpretive declarations" to their ratification, insisting that the Federal government could not determine the status of ex-slaves in those states. The declarations were, in themselves, neither here nor there, being merely statements with no authority. A few of the ex-Confederate states held out; Mississippi didn't ratify until 1995.

With Georgia's ratification, Johnson declared the Union restored. The Radical Republicans in Congress did not agree. Congress had returned to session on 4 December, with representatives and senators from eight Southern states then demanding to be readmitted. They included Confederate generals, cabinet secretaries, congressmen, and even the Confederate ex-vice-president, Alexander M. Stephens -- though admittedly, Stephens had been from first to last far from the most enthusiastic of secessionists, proving an insufferable critic of Jefferson Davis.

Congress, as per the Constitution, made its own rules. The Southerners were all angrily refused admission, with Congress setting up a Joint Committee on Reconstruction to define a different program. A violent collision between the legislative and executive branches was brewing.

* Although the Radicals were extreme, Johnson did much to pointlessly antagonize them, and to undermine his public position by his indifference to the troubles of the free black people. Johnson wanted no part of land redistribution to help free blacks, since he shared the common view of many Southerners that giving property to black people would make it more difficult to keep them down. Johnson pardoned the original plantation owners, their old property rights on the islands were re-affirmed, and the black folk were driven off.

That was the way Johnson wanted it. Although he hated the Southern aristocracy, he felt the planter elite would control the black folk, and chose to restore the planters as the lesser of evils. Johnson's lenient attitude towards ex-Confederates was much less driven by forgiveness than a determination to maintain white supremacy. In some cases, Federal troops performed the evictions.

Southerners clearly appeared to be taking remarkable measures to keep the black people suppressed. All four of the Confederate states recognized by the Johnson Administration passed "Black Codes" -- sets of laws that guaranteed free blacks certain rights, such as the right to marry, while denying them many more. Blacks could not bear arms, did not have the right of free assembly, could not serve on juries, could not testify against white people in court, and had limited personal and economic freedoms. At their worst, the Black Codes were designed to restore slavery under a set of legal fictions. Johnson did nothing about the Black Codes.

Even though the rights of black people were not at the top of the list of concerns of most of the Northern public, the measures taken by the Southern states to suppress blacks, and the bland acceptance of those measures by the Johnson administration, antagonized Congress and the public. They asked: why had the Union fought and won the war at such cost, to have a president then let Southerners do whatever they pleased? In fact, Johnson seemed to be in outright collusion with Southern reactionaries when he had vetoed in February a two-year extension of the life of the Freedman's Bureau -- it was only supposed to have lasted a year following the end of the war -- on the basis that the Constitution did not sanction such organizations.

Johnson's acts, or refusal to act, had so far been more disturbing than damning, but on 22 February 1866, he politically shot himself in the foot. A crowd came to the White House to listen to him speak; he grew hot and said wild things, implying some of the Radicals were traitors, specifically naming Sumner and Stevens among others, and even hinted that the Radicals were planning to assassinate him. Johnson succeeded only in antagonizing the moderates and enraging the Radicals.

In March 1866, Congress passed a "Civil Rights Bill", which was intended to nullify the Black Codes by banning discriminatory state laws. The act declared that all persons born in the USA who were not subjects of a foreign power were citizens, regardless of their skin color or if they had been slaves. All citizens, white and black, had the same rights to justice and property; to make and uphold contracts; to sue or be sued; and to give evidence in court. Johnson vetoed the bill, with the veto then overridden by one vote. It was the first time in American history that Congress had overridden a presidential veto on a major bill.

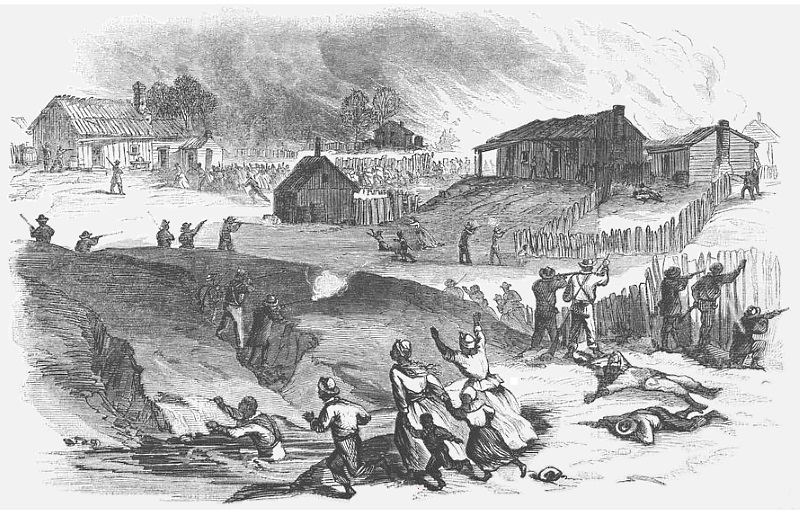

The political drama went on against a backdrop of continued outrages in the South. Southerners hated the sight of black men in Union Army uniforms, and after a few soldiers got into an altercation with Memphis city police on 30 April 1866, a white mob rampaged through the black districts of the city for three days, killing 47, injuring more than 80, and burning 16 churches -- with only one of the mob injured. Johnson said nothing, implying to critics that he tacitly approved of the intimidation designed to keep the free blacks in their place.

Congress redoubled efforts, pushing through an act in May extending the life of the Freedman's Bureau. The act also extended the Civil Rights Bill, granting ex-slaves "any of the civil rights or immunities belonging to white persons, including the right to ... inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold and convey real and personal property, and to have full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and estate, including the constitutional right of bearing arms."

The comment on the "right of bearing arms" reflected on a redefinition, generated by the conflict, of the Constitution's 2nd Amendment, which guaranteed the right of citizens to bear arms. Originally, the primary intent of the 2nd Amendment had been set up to support state militias, which were in principle to be the backbone of America's ground forces. By the time of the Civil War, militias were largely an obsolete concept; in its new reading, the 2nd Amendment was seen as emphasizing the right of citizens to own arms for self-defense. The Black Codes had attempted to deny weapons to black folk; one of the 14th Amendment's objectives was to ensure that black folk could own weapons to protect themselves.

BACK_TO_TOP* Despite increasing polarization, when the Congressional Joint Committee on Reconstruction then finally produced its own plan for Reconstruction, proposed as a 14th Amendment to the Constitution, it was a reasonable compromise. The proposed amendment was a complement to the 13th Amendment. The 14th Amendment was an extension of the Civil Rights Bill, with four major features:

The 14th Amendment was, in some ways, more revolutionary than the 13th. The Federal Constitution, notably the Bill of Rights, defined the rights of American citizens; but it only bound the Federal government to respect those rights, it did not bind the states to do so, they could define rights more or less as they liked. In crisp clear language, the 14th Amendment cut States' Rights down to size:

QUOTE:

No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

END_QUOTE

In 1857, in the case of DRED SCOTT V. SANDFORD, the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Roger Taney had judged that black Americans, even free blacks, had no rights as citizens, since they were "beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race." The 14th Amendment was a loud and emphatic rebuke to Taney, not only affirming the rights of blacks as citizens, but informing the states that they had to respect the rights of citizens as established in the Federal Constitution. Congress voted for the amendment in mid-June 1866, and it was then sent out to the states for ratification. In any case, Johnson obstinately called for the amendment's defeat.

Further outrages took place in the South. On 30 July 1866, a confrontation in New Orleans between black and white Republicans on one side and white-supremacy Democrats on the other led to an attack on the Republicans that killed 37 and injured more than 200, with 1 to 4 of the attackers killed and 20 wounded. Johnson did nothing.

There seemed to be hope for the 14th Amendment when Tennessee ratified it, but that was misleading; the other ex-Confederate states all voted against it. Kentucky and Delaware also voted against it, and the final tally was 25 states for, 12 states against. The 14th Amendment was defeated. Whatever satisfaction those who had fought against it felt was shortsighted; those who refused to play the game had not stopped it, simply dealt themselves out of it. What little spirit of compromise the Radicals felt was dead.

* There were Congressional elections in 1866; the campaign rhetoric was very hot, with Radicals comparing Andrew Johnson to Judas Iscariot and Benedict Arnold. Johnson went on an 18-day speaking tour on a special train in support of Democratic candidates, and blasted the hard-core Radicals as traitors in return, comparing himself to Jesus on the cross. Republican hecklers harassed Johnson at some of his stops, and in a few cases he got into angry exchanges that further damaged his credibility.

His enemies claimed he had been drunk while making his speeches, though those who knew Johnson well replied that he always spoke hot and wildly on the stump. Johnson would have helped the Democratic cause better had he stayed in the White House and not said a word.

The abuses in the South and Johnson's lack of finesse played into the hands of the Radicals by inflaming public opinion in the North. The Republicans won a mandate they couldn't possibly have achieved otherwise, obtaining huge majorities in both houses of Congress that could easily override Johnson's vetoes. Congress passed a set of four "Reconstruction Acts" from the spring of 1867 into the spring of 1868. Johnson vetoed them all, and was overridden in each case.

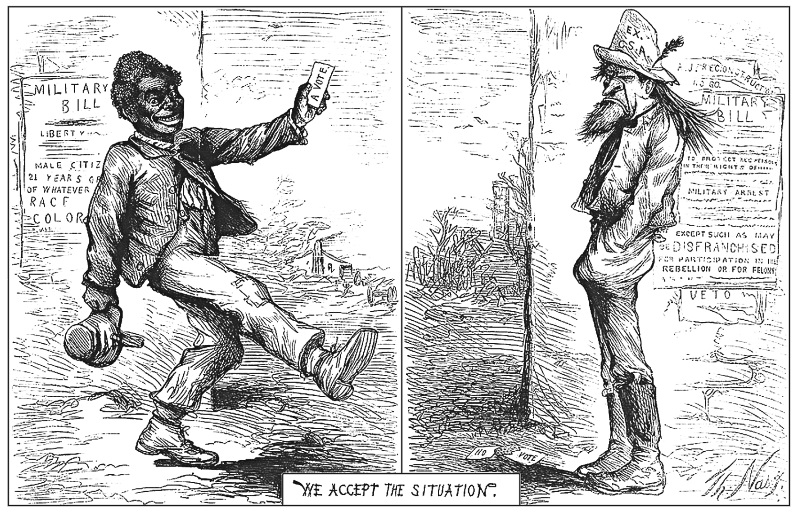

It was the First Reconstruction Act, enacted on 2 March 1867, that defined the new order, the other three acts being clarification and elaboration of the first. Congress rejected the legitimacy of the governments of all the ex-Confederate states except Tennessee. In the place of those state governments, Congress established a total of five military districts, bluntly named "conquered provinces", each under the rule of an army general. The military governments of the districts were instructed to register the adult males as voters, and they did so, with more emphasis on signing up blacks than whites.

Once the registration of voters was complete, the voters could then elect a convention to set up a state constitution. For the state constitution to be recognized, it had to guarantee black suffrage. The voters were then to ratify the state constitution, elect a state government, and ratify the 14th Amendment. The state government would be readmitted if Congress approved. The defiance of the Confederate states in rejecting the 14th Amendment had now come back to haunt them: they were going to have to swallow it, like it or not.

The military governors were quickly appointed. General John Schofield took over the first district, Virginia; General Dan Sickles the second, consisting of North and South Carolina; General John Pope the third, consisting of Georgia, Alabama, and Florida; General Edward Ord the fourth, consisting of Mississippi and Arkansas; and General Philip Sheridan the fifth, consisting of Louisiana and Texas. Tennessee escaped military rule.

The Freedman's Bureau was a prime mover in the voter registration effort, with assistance from Republican Loyal League and Union League organizations. When the registration was done, there were 703,000 registered black voters versus 627,000 registered white voters. Some of the whites had been denied voter registration, but they were few in number; many others simply boycotted it. That proved counterproductive, since it gave the Republicans majorities and control in all ten ex-Confederate states.

The new Republican state governments still were under overall military control, but the military governors were not as a rule eager to interfere with the workings of the states under their supervision. The generals had no explicit guidelines for their decisions. Providing such guidelines would have made things difficult, considering they were in a position that was unprecedented in the country's history, and detailed instructions passed down from the top would have tied their hands. However, at the same time, anything they did could easily be, and often was, politically controversial.

Sickles and Sheridan were unusual in their energetic enforcement of the Reconstruction Acts. Sheridan was loudly denounced as "King Philip", and Southerners were relieved when he was reassigned, to be replaced with General Winfield Scott Hancock, and then General Lovell Rousseau; neither of them was inclined to rock the boat. Rousseau was so lenient that when he died in office, New Orleans gave him a massive funeral ceremony as a measure of public appreciation. In fact, President Johnson reassigned all the original military governors except Schofield, replacing them with generals who took a minimal view of the job.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Radicals in Congress, having seized control of Reconstruction from Johnson, were not any more inclined to let the judiciary interfere with their agenda. When the Supreme Court attempted to limit the powers of military courts in the military districts, Radicals in Congress passed measures to limit the Supreme Court's authority in return, and the court meekly backed off.

However, the real target of their hatred remained Andrew Johnson. To protect Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, the Radicals' inside man in the Johnson Administration, Congress passed the "Tenure of Office Act", enacted in March 1867, which prevented the President from removing civil officials, even his cabinet secretaries, without Senate approval. Since General Grant, now in top command of the US Army, supported the Radicals' focus on military rule of the conquered Confederate states, at the same time Congress also passed the "Command of the Army Act", which forbade the President to give orders to the Army except through the commander of the Army, ensuring that Johnson couldn't bypass Grant.

Both of these measures were blatantly unconstitutional overreach of Congressional powers, violating Johnson's authority as commander-in-chief, and would eventually be nullified, but they indicated both the might of Congress and that body's hatred of Johnson. Even though Johnson no longer had the power to be a serious obstacle to the Radicals, they looked for pretexts for removing him from office, and he finally gave them one when he sacked War Secretary Stanton in defiance of the Tenure of Office Act. Stanton barricaded himself inside his office and refused to give it up for a time. Johnson defended the action on the basis that the act was clearly unconstitutional, and the only thing he could do to force a judicial decision to that effect was violate it.

The Radicals in the House framed 11 charges of impeachment against Johnson, voting in favor of them by 126 to 47 on 24 February 1868. It was the first time in American history that an impeachment of a president had been put into motion. Two-thirds of the Senate, meaning 36 senators, had to vote in favor of the articles of impeachment to remove Johnson from office. There were 42 Republicans in the Senate and only 12 Democrats, and Johnson's prospects for political survival did not look very good.

The trial began in March 1868 and became, in modern terms, a media circus. Reporters crammed the galleries and ran off to telegraph hot scoops to their newspapers. Chief Justice Salmon Chase presided over the court, doing his best to be neutral in his decisions. Five lawyers represented Johnson for the defense, and a committee of seven representatives appointed by the House handled the prosecution.

The most prominent of the prosecutors was Ben Butler, now a Republican representative. Butler did most of the talking for the committee. Butler made history of sorts when he held up a bloodstained nightshirt supposedly worn by a Mississippi official from Ohio who had been flogged by local thugs; from that time on, comparable theatrics in Congress have been described as "waving the bloody shirt".

Thaddeus Stevens was also on the committee, though he was in such poor health that he once had to be carried in to the proceedings on the chair, and in fact he would die in August, at age 76 -- to be buried at his insistence in a Negro cemetery.

* As is typical of media circuses, the event stretched out, going into April and May. Butler damaged the prosecution's case with an overblown charge that Johnson had tried to install a dictatorship, while Johnson's defense was consistent and competent. Johnson, having learned his lesson, was uncharacteristically subdued and even made concessions to Radical doctrine. Time was on the side of the defense, since the charges against Johnson were thin, and all his accusers could really do was posture; his defense only had to stall for time, and let the prosecution's case die of boredom.

The defense strategy worked. The public, as well as politicians who didn't have such an axe to grind, tired of the proceedings and the posturing. Republican Senator William Fessenden of Maine said that he could vote against Johnson if he "were impeached for general cussedness," but pointed out "that is not the question to be tried."

The matter came to a vote on 16 May. The House committee asked for a vote on the 11th charge, which was a blanket item that covered most of the serious accusations against the President. Fessenden and six other Republicans broke ranks and the vote lost, 35 to 19, just one vote short. The House committee called for a ten-day adjournment, and during that time the breakaway Republican senators were put under intense pressure. Despite this, or maybe because of it, when the trial was resumed and the next two charges were put to a vote on 26 May, the vote went the same way.

Justice Chase dismissed the proceedings, and the Radicals gave up on their crusade to throw Johnson out of office. A HARPER'S cartoon showed Horace Greeley --the editor of the NEW YORK TRIBUNE, who had been loudly calling for Johnson's head in editorials -- being revived after passing out in his office at the TRIBUNE on hearing the news, while "King Andrew" whooped it up with a bottle of booze in his hand, trailing his tailor's shears on a string. One of the breakaway Republican senators, Edmund Ross, was loudly denounced as a "traitor and poltroon" and lost the next election. He would not be rehabilitated for 20 years, after the hysteria had died down and people realized he had done the sensible thing when the crowd around him had rushed over the edge into lunacy.

* The impeachment proceedings were a complete farce in hindsight, since 1868 was an election year, and there was no way Andrew Johnson was going to be elected to a second term; there was no way the Democrats were going to back him for re-election. He would be out of office in less than a year, and in the meantime, confronted with a very hostile Congress, he had no way of accomplishing much. In fact, even with the failure to impeach Johnson, the Radicals were at the height of their power. The Reconstruction Acts remained in force, the ex-Confederate states were forced to comply, with the 14th Amendment enacted on 9 July 1868.

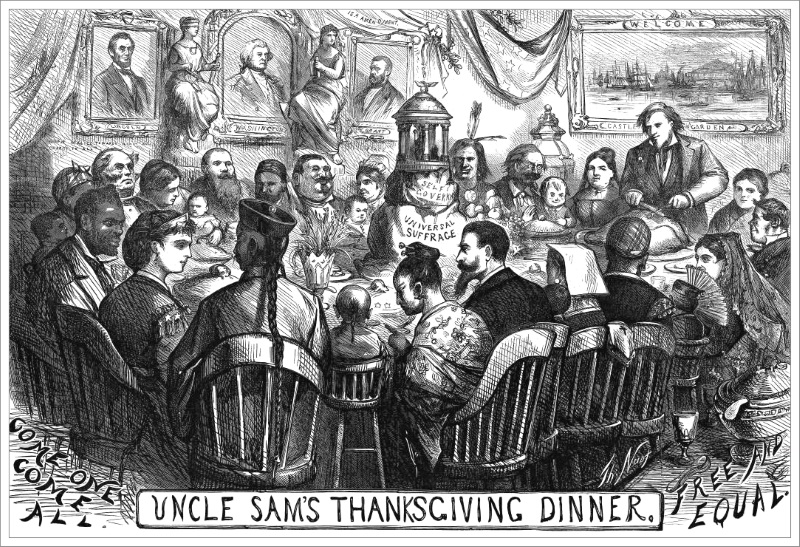

The 14th Amendment guaranteed civil rights; it did not guarantee political rights, most significantly the right to vote. Ironically, while Congress pushed black suffrage in the South, black men didn't have the right to vote in many states of the North. Southerners were quick to point out that the North was forcing rules on the South that Northern states didn't follow themselves. This hypocrisy was far too blatant, and so the Radicals devised the 15th Amendment of the Constitution.

The amendment's central clause read: "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color or previous condition of servitude."

This eliminated in principle the racial double standard between North and South and gave the Federal government a powerful legal lever against Southern reactionaries. The amendment was voted through by Congress in February 1868. Congress made it clear to reluctant ex-Confederate states that their readmission was dependent on ratifying the 15th Amendment.

In 1869, the Supreme Court lent its weight to Reconstruction in the case of TEXAS V. WHITE. The issue was that the secessionist government of Texas, in an exercise underlining the confused nature of the Confederacy, sold US Treasury bonds held by the state of Texas. The postwar government of Texas claimed the sale of the bonds by the secessionist legislature was illegal, and wanted the bonds back.

The court, under Chief Justice Chase, decided for Texas, declaring secession illegal and all legal actions -- aside from practical criminal and civil actions, such as issue of marriage licenses, that did not involve the rights of the central government -- of the secessionist Texas government null and void. The Federal government was also judged within its rights to suppress the secessionist state government, and to ensure that Texas had a proper republican government.

The 15th Amendment was enacted in February 1870, much to the joy of black Americans and their white sympathizers. It led to controversy among pioneering feminists, since it only gave all men the right to vote; some of the feminists felt it was a step in the right direction, others felt it was a misstep. Women's rights were an issue to be resolved by a later generation.

In any case, it seemed Reconstruction was working as planned; by the time the 15th Amendment was passed, six of the ex-Confederate states were back in the Union, with the rest returned to the fold by the middle of 1870. However, by that time, the Radical Republican governments of the ex-Confederate states were in gradual retreat, with "Redeemer" governments taking power in state after state, marked by a barely-concealed agenda to undermine the rights of their black citizens.

BACK_TO_TOP