* In late 1862, Union General William Rosecrans began his advance on the Confederate base at Murfreesboro. Confederate General Braxton Bragg held his ground, resulting in a brutal fight in wintry weather over New Year's Day. Both sides were badly mauled, but Bragg decided to withdraw, giving the Union something resembling a victory.

* In late December 1862, Rosecrans decided it was finally time to take the offensive against the rebels -- despite the fact that mid-winter was hardly the best time for military operations. One observer commented that winter in Tennessee meant "cold, and snow, and rain, and boundless mud." One of the big reasons to move despite the season was the Confederate preoccupation with Grant and Vicksburg: Bragg had transferred 9,000 men to help defend the city, and Rosecrans had got wind of the move.

On Christmas day, Rosecrans passed out orders directing the Army of the Cumberland to move out the next day, and had a council of war with his generals. At the end of the meeting, he slammed his mug on the table, stood up, and said: "We move tomorrow, gentlemen! We shall begin to skirmish, probably as soon as we pass the outposts. Press them hard! Drive them out of their nests! Make them fight or run! Fight them! Fight them! Fight, I say!" As the generals left, he firmly shook each man's hand: "Fight! Keep fighting! They will not stand it!"

A heavy rain fell that night. At dawn, the Federals left Nashville with a total of 45,000 men, roughly half of Rosecrans' command, with the other half remaining to protect the city and the vital rail links. The offensive force was organized in three columns: three divisions under Major General Crittenden to the east, three divisions and a cavalry brigade under Major General McCook in the center, and a division and three brigades under Major General Thomas to the west. The troops had a soggy, muddy, cold, and damp time of it, but they pressed on anyway.

As Rosecrans had predicted, the skirmishing began immediately. Joe Wheeler was particularly skillful in performing a fighting withdrawal, standing and fighting to force Rosecrans' men to deploy for a battle and then pulling out when pressure was firmly applied. To the south, Bragg had his 37,000-man command arranged in a 30-mile (48-kilometer) arc around Murfreesboro; he was frantically trying to consolidate his forces to meet the Federal offensive.

By the night of 27 December, Bragg had achieved consolidation. The land around Murfreesboro seemed straightforward on a map: Stone's River snaked in a winding way from southwest to northeast about a mile to the west of the town; the Nashville Turnpike cut northwest from the place, roughly paralleled by the Nashville & Chattanooga railroad, while the Franklin road ran towards the west. However, the terrain itself was broken, with clumps of cedar forest, hills, and ravines making for anything but a neat playing board.

Unsure of where the blow would fall, Bragg deployed General Hardee's two-division corps to the west of the river, near the Franklin road, and General Polk's corps, also of two divisions, to the north of that position. A division under Major General J.P. McCown was left behind the line in the center as a reserve. Bragg extended his defense to the northeast on the other, eastern side of the river, with nothing more than a line of skirmishers and scouts. Hardee found his position uncomfortable. As he wrote later, "the field of battle offered no peculiar advantages for defense. The country on every side was open and accessible to the enemy." Private Sam Watkins of the 1st Tennessee, under Polk's command, wasn't happy either. He felt he was on the "wrong side" of the Stone's River -- "on the Yankee side," he wrote. "Bad generalship, I thought."

Confederates inspecting a map might indeed have found setting up a line of battle with their backs to a river unsettling. However, for the moment, the river was very low and generally fordable due to the drought conditions of the summer and fall -- though with rains falling, nobody knew how long that would last. As far as the terrain being unsuitable for defense, defense was not what Bragg had in mind. In any case, Bragg positioned his own headquarters in between Polk's corps and the river.

The Federals now moved in. Crittenden's corps approached the Confederate lines in the late afternoon twilight of 29 December. Rosecrans' intelligence was poor; as usual, Yankee cavalry found themselves unable to make themselves very useful, and Rosecrans thought Bragg was pulling out. Crittenden had been ordered to send in a division to occupy Murfreesboro and move the rest of his corps to the west of Stone's River. Crittenden moved forward aggressively, made contact with Bragg's forces -- then thought the better of making a fight of it for the moment. He sent word back to Rosecrans describing the Confederate dispositions, to then wait for the rest of the Army of the Cumberland to arrive. Crittenden's men spent a wet, cold night on the line, since orders had been passed down not to make fires. In the meantime, Bragg, realizing that it would take time for Rosecrans to get his forces in place, ordered Joe Wheeler to ride his men out and harass the Federal rear.

* Early the next morning, 30 December, Rosecrans arrived with his staff, and McCook's and Thomas's men began to file into line of battle. With Crittenden on the north of the Federal position, Thomas was sent into the center, and McCook ordered to the south.

While the Yankees prepared to fight, Wheeler was having a fine time harassing Rosecrans' supply line. He captured McCook's supply train, consisting of 300 wagons and 700 men. He burned the wagons and paroled the men, and then seized another train of 150 wagons. All in all, his raid destroyed all or part of four wagon trains and captured 1,000 Federals; he returned with enough weapons for a brigade and many fresh horses. Wheeler's men thought it great fun, and the Union men they captured weren't all that unhappy with it, either; under the terms of their parole, they were obligated to stay out of the big bloody fight that was brewing along the Stone's River.

As troublesome as Wheeler's raid was, Rosecrans remained focused on the battle that he would launch the next morning. Unfortunately, he gave orders to his generals verbally, a procedure that was likely to lead to confusion. In broad outline, Rosecrans intended to send two of Crittenden's divisions forward on the north, while Thomas sent two divisions into the center of the rebel line and McCook kept the Confederates pinned down on the south.

Rosecrans ordered McCook to light a large number of campfires that night in order to confuse Bragg. It was a silly trick, but Bragg fell for it. The end result, however, was that Bragg not only moved his forces during the night to meet the expected Federal thrust, but gave them orders to take the offensive. The Federals intended to attack along the north of the line, the Confederates, along the south, and in principle they could end up wheeling around each other.

As the sun went down, a Union regimental band struck up with a set of Yankee favorites. Then the Federals stood by while a Confederate band replied with tunes of their own. This exchange continued until finally, a Federal band started "Home Sweet Home"; a Confederate band joined in, then another band, and another band, until they were all playing it and the soldiers were singing along. When it was done, there was nothing but a chill lonely stillness echoing through the evening.

During the night, Bragg's rebels moved into final positions where they would be prepared to give battle the moment the sun came up. Since the Federals had arrived, McCown's division had been moved to the southern end of the line. Hardee had sent one of his divisions, under John C. Breckinridge, to extend the north end of the line east of the Stone's River to meet a possible flanking attack. Hardee took command of McCown's division to use it in partnership with one of Hardee's own divisions, under Major General Pat Cleburne, for the dawn charge on the Yankees.

Confederate movements did not go entirely unnoticed by the Federals. In the dark hours of the morning on the last day of 1862, Major General Phil Sheridan, one of McCook's division commanders and now deployed on the south of the Federal line, was roused by one of his brigadiers, General Joshua W. Sill, an old West Point colleague. Sill had observed Confederate infantry moving through the night to take up positions for attack.

Sheridan was concerned and rode with Sill to warn McCook. McCook was sleepy and indifferent, saying that Rosecrans was aware of the situation and that nothing had changed. Sheridan was not reassured; he returned to his division, walked up the line and ordered his 12 regimental commanders to wake their men, let them eat breakfast, and prepare to meet an attack at sunrise. The warning filtered back to the commanders of McCook's other two divisions, Jefferson C. Davis and Richard W. Johnson. By that time, McCook had roused from his drowsy complacency, and finally passed down an order putting his corps on alert.

Two Federal brigades, under Brigadier Generals August Willich and Edward N. Kirk, held the far right of the Federal line. Willich, after sending out scouts, apparently concluded there was nothing to worry about for the moment. At sunup, he let his men make breakfast. Kirk's men were somewhat better prepared for a fight.

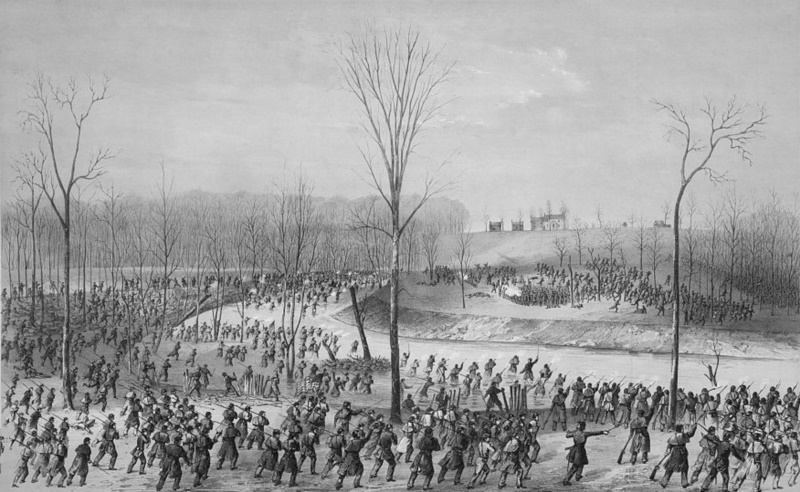

At about 6:00 AM, Hardee's two divisions of Confederates, 11,000 strong, came advancing in a line six-deep. They remained quiet until they got into rifle range, then let out the unnerving rebel scream. Despite the advance warning, many of the Yankees on the line were taken completely by surprise and were scattered by the momentum of the rebel charge, some throwing down their weapons and crying out: "We are sold! Sold again!"

Willich was absent at the moment, having left to confer with Johnson. Kirk ordered one of his regiments, the 34th Illinois, to counterattack, while he sent word back to Johnson that the Confederates were on him. The 34th Illinois collided with the Confederates and inflicted severe casualties on them. The Illinois men were badly cut up themselves, however, and were thrown back into their lines. The rebels continued their rapid advance while Kirk's men fired volleys into their line; the Yankee fire hurt the Confederates, but they persisted, scattering the Federals when they made contact. Kirk was shot, taking a lingering wound that would kill him in six months. He shouted that his men should get out and escape capture.

Willich's soldiers were still trying to get to their weapons when the blow fell on them. With Kirk's men fleeing alongside them, they broke immediately. Complete confusion took over in that section of the Federal line. A brigade of Confederates swept around the Union right, and rebel cavalry charged into the Yankee rear. Things became so confused that when Willich came back and tried to rally his men, he discovered that the soldiers he was shouting orders to were Confederates, who shot his horse and took him prisoner.

The two Federal brigades ceased to exist; the survivors did not stop running until they were far in the rear. A Confederate prisoner who had been captured before the battle, Private Joseph T. McBride, was so disgusted at the rout of the Federals that he called out to the fleeing Union men: "What are you running for?! Why don't you stand and fight like men?!" A fellow prisoner roared at him: "For God's sake, Joe, don't try to rally the Yankees! Keep 'em on the run!"

Major General Jeff Davis heard all the ruckus on his right and ordered one of his brigades to turn 90 degrees to face the assault; one of Johnson's reserve brigades moved up among boulders and trees to extend the line. Four of Cleburne's brigades hit them hard, but the Union men, though outnumbered, poured fire into their attackers. One enthusiastic Federal regiment even countercharged.

In the center, at about 7:00 AM, Polk ordered two brigades forward to assist in the Confederate drive, but one brigade failed to move out and left the other, consisting of Alabamans under Colonel J.Q. Loomis, completely exposed to the fire of the Yankee line. They were "mowed down as a grass beneath the sickle." Cut up, the attackers fell back to their own lines. Rumors would later go around that their division commander, Major General Cheatham, had been drunk, though Sam Watkins saw him personally leading attacks.

* In the meantime, on the north end of the battlefield, Rosecrans had begun his own assault against the rebels. He had ordered one of Crittenden's divisions to advance across Stone's River towards John Breckinridge's Confederates, with a second division to follow. The sounds of firing from the rebel push to the south became audible and then steadily louder, a snapping and popping noise, sounding like a "cane break on fire", as one observer wrote later. Rosecrans heard the Confederate attack, but assumed that his forces could contain it. However, at about 7:00 AM, the rumbling grew louder and the debris of stragglers, wounded, and riderless horses made it obvious that all was not going well for the Union Army of the Cumberland. Reports were confused for a while -- but when Rosecrans heard that Willich had been captured and got an urgent appeal from McCook for reinforcements, he ordered George Thomas to send a division to assist, and recalled the two divisions that had crossed Stone's River.

The rebels were now focused on a section of the southern end of the Federal line, defended by two brigades of Jeff Davis's command and Sill's brigade of Sheridan's command. Federal resistance was so stiff that Polk had to commit a brigade of Texans and Tennesseans to the assault. The rebels broke Sill's line, but they became mixed up at the point of contact; the Federals counterattacked and drove them back. Sill was killed by a bullet in his brain, but the Confederate attack was broken for the moment.

The quiet did not last. Cheatham ordered his four brigades forward against Davis's brigades, and with Cleburne's men moving around them, the Union men's endurance finally gave way; they broke and fled. Sheridan recognized the crisis and shifted his own lines to meet the flank assault. By 10:00 AM, the Federal lines had been shifted into a "V" shape, bent around the line of the Nashville Turnpike, with Sheridan's troops holding the tip of the salient under severe pressure. One witness wrote: "Death and blood everywhere." An Illinois artillery battery fought to the last, defending their guns with sabres, pistols, and ramrods until they were finally overwhelmed. Sheridan was forced to pull back, but did so in good order and reformed to meet further assaults. Confederate attacks continued to pour in.

The Federals had been hurt badly, but the Confederates were paying dearly as well. Both Hardee's and Polk's corps had lost about a third of their men. The rebels still persisted, hoping that one more big push would finally crack the Yankees. At about 10:00 AM, Hardee sent a request to Bragg for reinforcements, and Bragg in turn ordered Breckinridge, on the quiet Confederate right, to send two brigades.

Breckinridge flatly refused; he was under the mistaken impression that the attack that Rosecrans had begun -- and then called off -- earlier in the morning was still about to fall on him. Bragg was in no position to question his subordinate's word, and in fact was receiving reports of Federal reinforcements moving down through the enemy rear to support such an attack. He ordered Breckinridge to advance and engage his attackers. Breckinridge did so, to be extremely surprised to find that the hordes of Yankees he had expected to see weren't really there.

On the Union side of the lines, Rosecrans was dashing around his lines with complete disregard for his own safety, doing everything to brace them against Confederate attacks. His conduct endeared him to his men -- though by becoming so involved in the fighting, he risked losing direction of the battle. A brigade under Colonel Samuel W. Price held the Federal line in front of Breckinridge's division. Rosecrans was aware that if Breckinridge threw his forces into the fight, the Union positions would be sorely pressed, and so blocking them was absolutely critical. He rode up to Price and demanded: "Will you hold this ford?"

Price replied: "I will try, sir!"

Rosecrans didn't like that answer, and said again, loudly: "Will you hold this ford?!"

"I will die right here!"

Rosecrans didn't want him to die, what was the use of that? "Will you HOLD this ford?!"

"Yes, sir!"

"That will do," Rosecrans said, and rode off to check on the security of his other threatened ranks.

Crittenden's men were filing up the right of the Federal line, lengthening and strengthening the defense against rebel flanking movements. Rosecrans' men were still being pushed back. At about 11:00 AM, Rosecrans found Sheridan falling back once more. Sheridan's men were running out of ammunition, and he swore angrily at having to withdraw when he should have been able to stand and fight. The devout Rosecrans reprimanded Sheridan: "Watch your language. Remember, the first bullet may send you to eternity." Sheridan found Rosecrans under obvious stress, but still calm and collected, and observed that his demeanor "inspired confidence in all around him."

Sheridan's fall-back left a major gap in the Federal line that the rebels tried to exploit, but the Union brigades on either side of the break performed a skillful fighting withdrawal. However, this left the center of the Union line, defended by a division under Major General John Palmer and holding ground in front of a dense grove of trees they called the Round Forest, exposed to a concentrated attack. The Confederates did their best to exploit this opportunity, but Rosecrans lined up artillery to help defend the Round Forest, and Palmer's men stood their ground. The Union guns could not miss and two Confederate brigades, one from Mississippi and one from Tennessee, shattered themselves against the Federal defense, to fall back broken.

* By that time, it was roughly noon. Rosecrans had stabilized the Federal right and provided ammunition to his men. Bragg decided that he could make no more headway there and decided to shift his attack northward.

In the Round Forest, the solid core of Palmer's division was a brigade under a nails-hard army regular, Colonel William B. Hazen. Hazen and his men had been standing firm, and Rosecrans had been throwing in everything he had to shore them up. At 1:00 PM, Bragg gave Breckinridge a direct order to send four brigades for an attack on Hazen's brigade in the Federal center. While the rebels shifted their forces the attacks fell off, though cannon fire remained intense, and Rosecrans and Thomas took the opportunity to roll in more artillery.

By 4:00 PM, the last day of 1862 was starting to fade away, but the Federals observed Confederate units massing for one last charge. They were the four brigades Breckinridge had been ordered to send to the center, and were now under the command of Polk. Polk realized that "the opportune moment for putting in these detachments had passed," but he was going to follow orders. Only two of the brigades had arrived; Polk sent them in. They advanced resolutely and silently, at least until Federal artillery started pounding them. On the Union side of the line, Hazen called back urgently for reinforcements to meet the charge. He got them, put them in line, had them all stay quiet until the rebels were in range, and then ordered them to fire a volley that tore the ranks of Confederates to pieces. The survivors fell back in disarray.

As the rebels returned to their own lines, they met Breckinridge coming up at the head of the other two brigades. The newcomers made a second advance, with similar results. Holes were blown in their lines by the 50 guns the Yankees had focused on them; soldiers were swept down by volleys when they got in range. They withdrew, leaving their dead and wounded in rows on the field. A Tennessee soldier wrote of the sight that had faced them in the charge: "In the fading light, the sheets of fire from the enemy's cannon looked hideous and dazzling."

Rosecrans and his staff were observing the fight from a rise behind the forest. When he felt that Hazen's men were faltering, Rosecrans galloped forward with his aides to provide moral support. A cannonball flew past him and blasted the head off of his chief of staff, Colonel Julius P. Garesche, while others were hit by Confederate bullets and shell. Rosecrans noticed none of this, riding into the midst of the regiments defending the Round Forest, his coat soaked with Garesche's blood, making many think their commander had been wounded himself. The men tried to tell him to get to safety, but he simply replied: "Men, do you know how to be safe?! Shoot low -- but to be safest of all, give them a blizzard, and then charge with cold steel!"

Drugged by adrenalin, Rosecrans seemed indifferent to the death of his aide, friend, and fellow devout Catholic Garesche, saying: "Brave men die in battle. Let us push on. This battle must be won!"

In reality, for the day the battle was over. Hardee, disconnected from his own men, rode up to Polk's lines and saw the slaughter of Breckinridge's soldiers. Darkness was falling swiftly, and Hardee ordered Breckinridge to cease his futile attacks.

As badly as the Confederates had been hurt, they were convinced they had hurt the Federals much worse, and had all but won the battle. In fact, Rosecrans and his generals wondered if they were beaten. The Union officers held a conference of war in a log cabin to the rear of their lines and discussed the possibility of retreat. They were all tired, dirty, and demoralized, the generals were divided and equivocal, and the meeting ended without a decision.

Rosecrans then scouted out a possible route of retreat, but he finally decided to stand his ground. He announced there would be no retreat. The Army of the Cumberland was low on supplies, but still had ammunition for a day's fighting; Rosecrans sent a wagon train back to Nashville under heavy escort to evacuate the wounded and bring back supplies. News of the wagon train got back to Braxton Bragg, and he concluded the Federals were withdrawing; he decided he would attack them in the morning and destroy them while they were strung out along the road to Nashville. Bragg wired Richmond:

THE ENEMY HAS YIELDED HIS STRONG POSITION AND IS FALLING BACK. GOD HAS GRANTED US A HAPPY NEW YEAR.

Bragg then went to bed without making a single preparation for the next day's fighting.

BACK_TO_TOP* No more miserable New Year's Eve could have been imagined than that at the battlefield around Murfreesboro. Cold rain fell in the darkness on thousands of dead and wounded strewn over the landscape. The wounded cried out for help; for water; for a fire; to God, or for their mothers; or simply to be shot and put out of their pain. Attending to the casualties was such a task that most of the dead could only be left where they had fallen, their blood freezing to the ground. A Louisiana man later remembered: "The earth was burdened with the Yankee dead. They were crossed and piled over each other, nearly all of them lying on their backs, with their faces so ghastly turned up to the moon." A Texan soldier claimed to have seen hogs feasting on the corpses.

When it grew dark and the firing fell off, Colonel Hazen left the Round Forest where he had led his men with such determination during the day to attend to another duty: to find the headless body of his old friend, Colonel Garesche. When Hazen found it, one of the arms was stuck outward. He removed the West Point ring from the cold hand, took Garesche's worn copy of THE IMITATION OF CHRIST, and had a detail take the pathetic corpse for a decent burial. A Federal officer spent the night tending to two badly wounded Confederates, giving them water when they asked for it. He left in the morning, and came back to find both men dead. Later he wrote: "Some kindly soul had covered their faces with hats and spread blankets over the remains."

Rosecrans was busy through the night, consolidating his positions in expectation of a morning assault. He pulled his troops back out of the Round Forest, reinforced his right, and sent Van Cleve's division -- now under Brigadier General Samuel Beatty, since Van Cleve had been wounded in the leg -- across Stone's River to occupy a hill where their guns could command Confederate positions within their range.

Rosecrans' presence and concern reassured his men. When he found a group of them clustered around a fire, he told them: "You are my men, and I don't like to have any of you hurt. When the enemy sees a fire like this, they know 25 or 30 men are gathered about it. I advise you to put it out." Moments later a shell landed just beyond the men. There was little food and limited ammunition, but Rosecrans was optimistic: "Our supplies may run short, but we will have our trains out tomorrow. We will keep right on, and eat corn for a week, but we will win this battle. We can and will do it."

* Bragg woke up on New Year's Day 1863, to the shock of finding that the Federals were still where they had been the night before. Never very decisive, Bragg didn't know what to make of it, and spent the day doing nothing particularly important, though after the bloodletting of the day before his army wasn't in condition to do much anyway. His men scavenged the litter of Federal weapons and equipment on the battlefield. Polk moved troops into the abandoned Round Forest, made contact with the Yankees, then decided it would be unwise to advance further. Breckinridge moved back into his positions on the right of the Confederate line. There was no more than skirmishing all day long. Just before sundown, heavy firing broke out, but it died out quickly.

Bragg had received reports of more wagon trains pulling out of the Federal rear and clung to his belief that the Federals were withdrawing, but the wagons were simply carrying wounded men on the agonizing 30-mile (48-kilometer) journey to Nashville. The Yankees stayed where they were, hungry but defiant. Wheeler's destruction of their trains left them without food, though Crittenden was pleased to have a "first-rate beefsteak" that turned out to be the final military service of a horse that had fallen in battle.

The next morning, 2 January 1863, while rain fell and turned to sleet, Bragg sent out skirmishers to see if the Union men were still there. They were; a vigorous exchange of artillery proved there was plenty of fight left in Rosecrans's army. Bragg decided to move guns to the high ground to the east to fire on the Federals -- only to find that this was the same position that Rosecrans had sent Colonel Beatty to occupy the previous night. Bragg suddenly realized that his own positions were exposed, and that the Federals needed to be swept off the hill. He called Breckinridge to headquarters and ordered him to attack, as a prelude for a new assault by Polk in the morning.

Breckinridge had been personally scouting out Beatty's position on his own initiative, and had judged it a deathtrap. There was much bad blood between Bragg and Breckinridge's men, particularly the "Orphan" 1st Kentucky Brigade, under Brigadier General Roger W. Hanson; they were called "orphans" because their state had fallen under Union control. Bragg, always a heavy-handed leader, seemed to pick on them, and the Kentuckians seemed in turn to be particularly touchy about any real or perceived slight. Matters had greatly escalated a week before, when Bragg had one of them shot for desertion in front of their formations, even though Breckinridge and his officers had pleaded for the man's life. Breckinridge had been so overcome watching the man shot that he had fainted and fallen from his horse.

In any case, Breckinridge loudly objected to the suicidal order to attack. Bragg simply grew angry and told him to obey. When Breckinridge relayed the order to his commanders, Brigadier General Hanson was so enraged that he threatened to go kill Bragg. Breckinridge, however, had swallowed his own misgivings and quieted Hanson and the others down, though he stated for the record that he objected to the attack. That afternoon, they began to move into position for the assault.

Their preparations did not go unnoticed by the Federals. At about 3:00 PM, Rosecrans and Crittenden started shifting such forces as they could spare to meet the threat. Crittenden's commander of artillery, Major John Mendenhall, concentrated 58 guns to support Beatty's position. At about the same time, Bragg visited Polk to order him to support the attack with his artillery. Polk objected to the attack, but as with Breckinridge, the protests were ignored: the attack would go forward as planned.

Polk's gunners began firing at 4:00 PM. Beatty moved his men back over the slope of the hill he occupied to protect them from the bombardment. Breckinridge shouted: "Up, my men, and charge!" -- and the gray ranks moved forward. The rebels moved in good order despite the Federal artillery. They closed the 600 yards (550 meters) to the Federal position and collided with it heavily. The forward line of the Yankees crumbled and broke. The Union men ran back in a rout, streaming through their reserve forces, who stood until they were flanked and had to withdraw.

Breckinridge's men had done the impossible: they had driven the Federals out of what Breckinridge had judged an impregnable defense. However, the rebels were so excited by their success that they refused to stop and consolidate their position, ignoring the shouts of their officers; they kept right on chasing after the runaway Yankees and moved into range of Mendenhall's batteries. One Federal said that the Confederates must then have believed they had "opened the door of Hell, and the Devil himself was there to greet them." The Yankees fired a hundred rounds a minute into the advancing rebels, shattering their attack. When they began to fall back they were struck by a Union brigade under Colonel John F. Miller, and the irresistible rebel charge disintegrated backward into a rout in turn.

Rosecrans threw other units into the counterattack, and Breckinridge's men scattered back to where they had come from. A Union colonel, observing both Federals and Confederates in mad retreat, later commented: "It was difficult to say which was running away the more rapidly, the division of Van Cleve to the rear, or the enemy in the opposite direction."

The fight had lasted less than an hour. As Breckinridge inspected the thinned-out ranks of his regiments, he raged "like a wounded lion", as one Kentucky officer put it. When he saw what was left of the 1st Kentucky, he cried out: "My poor Orphans! My poor Orphan Brigade! They have cut it to pieces!" Hanson might have agreed with him, but he had been mortally wounded on the field of battle.

* The rain and sleet had let up for a while near dusk, then started again after dark. It was another bloody and miserable night. Both sides had been stunned at the magnitude of the casualties in the three days of intermittent but savage fighting, and were on the edge of collapse.

When a local minister asked permission to take the body of a dead Confederate brigadier to Nashville, the man's home town, for burial, Rosecrans charitably assented, but added emphatically: "I wish it to be distinctly understood that there is to be no fuss made over this affair. I will not permit it, sir, in the face of this bleeding army! My own officers are here, dead and unburied, and the bodies of my brave soldiers are yet on the field. You may have the corpse, sir; but remember distinctly that you cannot have an infernal secession 'pow-wow' over it in Nashville!"

Rosecrans had overcome his doubts about standing his ground and prepared for yet another attack, ordering his men to dig in. He sent three loud-voiced officers and a group of men along the eastern parts of his line. They shouted commands, made a lot of noise, and lit campfires to simulate large troop movements. At about 9:00 PM, Rosecrans returned to his headquarters, wet and muddy, but still enthused, chanting: "Things is workin'! Things is workin'!" Reinforcements, consisting of two brigades from Nashville, plus a wagon train of supplies and ammunition, began to trickle in. Things were working, and the situation was incrementally improving for the Federals.

Meanwhile, things were incrementally growing worse for the Confederates. The rain was finally swelling Stone's River, threatening to cut off their units to the west of it, and Bragg had no effective source of resupply. Rosecrans's attempts at deception were also proving remarkably effective. As the night wore on, Bragg and his generals grew ever more discouraged and intimidated. In the dark hours of the morning, Polk sent a message to Bragg, informing him of the difficult position of the rebel army, and concluding: "I very greatly fear the consequence of another engagement at this place. We could now, perhaps, get off with some safety and some credit, if the affair is well managed."

Bragg's response was predictable, telling the courier that had borne the message: "Say to the general we shall maintain our position at every hazard." Polk sent a note to Hardee, commenting that Bragg's decision to stand was "unwise, in a high degree."

BACK_TO_TOP* After the sun came up on 3 January, Bragg reconsidered his decision. Wheeler's cavalry informed him of the reinforcements arriving to bolster Rosecrans, and captured Federal documents somehow gave Bragg the impression that there were 70,000 Yankees facing him. At 10:00 AM, he called a council of war with Hardee and Polk. They quickly agreed that the Army of Tennessee had to pull out.

The rebels began withdrawing that afternoon. The battle was over. Rosecrans was surprised that the Confederates were leaving; he did not pursue. Bragg moved his men to a line between Murfreesboro and Chattanooga, setting up headquarters in the town of Tullahoma, Tennessee.

The fight had been desperate, with a little less than 12,000 casualties on the Confederate side and a little more than 13,000 on the Federal side, in total bloodier than either Shiloh or Fredericksburg. Tactically it might have seemed a draw, but strategically the South could not think of trading the Yankees man for man. Rosecrans had done much to tighten the Federal hold on Tennessee, as well as pour more cold water on the widespread but wavering Confederate sympathies of Kentuckians, who were not inclined to back a losing side.

President Lincoln, still under the burden of the ghastly Union defeat at Fredericksburg, Virginia, in December was relieved to have something that had much the appearance of a victory, however expensive, and wired Rosecrans:

GOD BLESS YOU.

Still, Rosecrans, after having fought a battle where he had let the enemy take the initiative through the entire fight, had then let the Confederate Army of Tennessee withdraw and regroup without making the slightest effort to interfere. Though it was certainly true that the Union Army of the Cumberland wasn't in any good condition to pursue, Rosecrans had simply postponed the day of reckoning between the two armies.

For the moment, though, Rosecrans was a hero, and if he was not acting the part with complete conviction, he was certainly talking it. On 5 January, he wired Washington:

I NOW WISH TO PRESS THEM TO THE WALL.

Braxton Bragg's decision to withdraw from the battlefield at Murfreesboro unsurprisingly exposed him to the most savage criticism of the poisonous Southern press, some claiming that he had retreated against the advice of his generals. Bragg was hardly the most objective of men -- since the battle he had been energetically blaming the defeat on everyone else, including his troops, who had fought with almost superhuman endurance and persistence -- but he was within his rights to be outraged by such accusations. He had belligerently resisted suggestions to pull out, doing so only when the facts in favor of it seemed overwhelming, and with the general assent of his senior officers.

Bragg decided to challenge the newspapers, and on 11 January 1863 he sent a letter to his corps commanders asking them to publicly back him up. That was fine, as far as it went, but Bragg then demonstrated an astonishing lack of judgement by adding: "I shall retire without a regret if I find I have lost the good opinion of my generals, upon whom I have ever relied as upon a foundation of rock."

It is very hard to understand what Bragg was thinking; he couldn't have been unaware that his relationship with his generals was not the best. Either he simply failed to think things out, or more likely was hoping that such an expression of confidence in them would be returned in kind. It wasn't. All five generals who received Bragg's letter agreed that he had not acted against their counsel at Murfreesboro, and all five said they had no confidence in him -- in some cases attempting feebly to temper the blow to Bragg's ego by praising his conscientiousness and honest character.

Hardee, for instance, replied: "Frankness compels me to say that the general officers whose judgements you have invoked are unanimous in their opinion that a change in the command of this army is necessary. In this opinion I concur." He added that he had "the highest regard for the purity of your motives, your energy, and your personal character," but was "convinced, as you must feel, that the peril of the country is superior to all personal considerations."

Jefferson Davis, never very patient, was greatly distressed by this ridiculous outburst of bickering in Tennessee, and Bragg's foolishness in provoking it. He wrote Joe Johnston: "Why General Bragg should have selected that tribunal and have invited its judgements upon him is to me unexplained; it manifests, however, a condition of things which seems to me to require your presence."

The letter caught up with Johnston while he was on an inspection tour in Mobile, Alabama, and he left for Tullahoma to investigate. Johnston's enthusiasm for his command and his hopes for military success in the West were not high. Having to go sort out such a petty mess could not have made him any happier.

With Braxton Bragg, unhappiness was something like a contagious disease. Everyone from Joe Johnston down to the lowest private in the Army of Tennessee seemed to be unhappy, with Bragg at the root of it. There was a story at the time that Bragg, not long after his retreat from Murfreesboro, had ridden up to a man and asked him directions. He was given them, and thanked the man. Since uniforms were informal at best in his command, Bragg did not know if the man was a soldier or civilian, and asked the fellow if he was part of Bragg's army. The fellow scowled and replied: "Bragg's army? Bragg's got no army. He shot half of them himself, up in Kentucky, and the other half got killed at Murfreesboro."

It is recorded that Bragg managed to laugh. Not many people in his army were laughing, and it is doubtful that his own laugh was particularly enthusiastic. Nonetheless, Bragg kept an iron grip on his command, knowing he would have a rematch with Rosecrans in the not-too-distant future.

BACK_TO_TOP* This document was derived from a history of the American Civil War that was originally released online in 2003, and updated to 2019. It was a very large document, and I first tried to simply break it into volumes for publication in ebook format; however, that proved unsatisfactory, and I decided to rewrite components of it to tell the story of famous battles and such. This stand-alone document was initially released in 2022.

* Sources:

* Illustrations credits:

Photos are typically from Brady Studios. Good photos of Confederate officers are rare -- the South, it appears, was backwards on cameras -- and it is unclear if most of them were taken postwar.

Finally, I need to thank readers for their interest in my work, and welcome any useful feedback.

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 may 22BACK_TO_TOP