* In the summer of 1862, Federal and Rebel forces confronted each other in eastern Tennessee, with Union General Don Carlos Buell facing off Confederate General Braxton Bragg. Buell was engaged in a plodding drive toward Chattanooga, Tennessee, that was going nowhere very quickly; Bragg derailed his plans with an invasion of Kentucky that quickly swept into the state.

* The outbreak of war between North and South in 1861 created two major fronts of action between the two sides: one in the East, focused in Virginia, and one in the West, focused on the Mississippi River. The primary goal of the Union in the West was to seize control of the Mississippi -- which would cut the Confederacy in half, and deprive the South of use of the river for communications and supply.

The Union drive got off to a good start in February 1862, when the Union Army of the Tennessee, under Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant, captured Forts Henry and Donelson, on the Kentucky-Tennessee border. That unhinged Confederate positions in Kentucky, leading to their withdrawal; Nashville, Tennessee, was bloodlessly occupied by Union forces on 25 February. The surrender of the two forts greatly encouraged the North, with Grant promoted to major general of volunteers.

The capture of the two forts led to a violent collision between Grant's forces and those of Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston on 6 & 7 April 1862, in the vicinity of Shiloh Church in Tennessee; the bloodletting exceeded that of all other battles in American history to that time. General Johnston was among the dead, being replaced by his second-in-command, General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard.

While the Confederate force had to withdraw, the great numbers of killed and wounded raised a huge outcry in the North and put Grant under a cloud -- with the theater commander, Major General Henry W. Halleck, taking effective command of Grant's force and sidelining him. At the end of May, Halleck captured Corinth, Mississippi, the main Confederate base in the upper Mississippi region. It was hardly any great victory; Halleck, a timid general, moved so slowly that Beauregard was able to withdraw all of his force and most of his materiel unmolested. Nonetheless, the Confederate defense of the region had become unhinged; on 6 June, a force of Union river ironclads and other warships -- under the overall command of Navy Flag Officer Charles Henry Davis -- defeated a scratch Confederate fleet at Memphis. The city was then occupied by the Federals. The Confederacy had lost control of eastern and central Tennessee.

* The fall of Memphis left Halleck in a very good position to strike against a weaker and demoralized enemy at will. Unfortunately, with Halleck in charge, "will" was not much in evidence. Halleck was a grumpy and inert general, preferring paperwork to fighting battles. Morale faltered in the ranks. Corinth was no prize in itself: there was little water there, a summer drought set in not long after the Federals arrived and made matters that much worse, and such water as was to be had was full of dirt and disease.

Halleck had overall control of an army of 120,000 men, enough to roll over any opposition the Confederates had in the region, but on 9 June he began to methodically dismember his own force. That was not without some reason: he had to hold down a large territory where the locals weren't always very enthusiastic about the Union cause, and besides, if all of his soldiers remained holed up in unhealthy Corinth through the summer, a good number of them would be struck down by disease.

Halleck ordered four divisions under Major General Don Carlos Buell to march east, to hook up with forces under Brigadier General Ormsby Mitchel. The combined force would then, in principle, drive on Chattanooga, Tennessee -- from where it could advance on Knoxville, Kentucky, or due south to Atlanta, Georgia. That was the only fighting Halleck planned for the moment.

Major General William Tecumseh Sherman was sent west to Memphis with two divisions to repair railroads and generally attempt to restore normalcy to the lives of the population. Major General John McClernand was also sent off with two divisions to Jackson, Tennessee, with the same mission. Halleck stayed in Corinth with the remainder of his force, where he provided direction for the other three parts.

One of the consequences of this shuffling was that Grant was put back in charge of what had been his old Army of the Tennessee, which gave him control over Sherman's and McClernand's commands; he set up his command in Memphis. In July, Halleck would be called to Washington DC to become the general-in-chief of all the Union armies; from there, Halleck would continue to exert some lesser or greater degree of long-distance control over Union forces in the West.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Union drive on Chattanooga had started out well. A division under Ormsby Mitchel had seized Huntsville, Alabama, on 11 April, to then continuing its advance towards Chattanooga. Chattanooga the key to the mountain regions If Mitchel could take Chattanooga, a central rail hub in the region, Knoxville would be open to an advance from the rear, and the Confederates would have to pull out.

A second Union division, under Brigadier General George W. Morgan, was positioned in front of Cumberland Gap, for the moment bogged down by mud and mountains. If Chattanooga fell, Morgan's division would then join hands with Mitchel's, and the combined force would seize Knoxville. The rebels would be cleaned out of East Tennessee -- with Atlanta, Georgia, then becoming the next logical target. However, Mitchel's drive had then bogged down.

On 12 April, a band of Unionist raiders in civilian clothes, under the command of a civilian scout named James J. Andrews, had gone behind Confederate lines and stolen a locomotive, the intent being to sabotage the rail network in the region. It was a bust; rebel forces quickly hunted the saboteurs down, some of them escaping, some being captured and hanged as spies -- Andrews among them. Mitchel hadn't the strength to do any more.

The arrival of Don Carlos Buell's force in June to help the drive on Chattanooga seemed to tilt the balance of power in the region back to the Union. The drive on East Tennessee was near and dear to President Abraham Lincoln's heart, since he wanted to support Unionists in the hill country, then chafing under Confederate domination. By early July, Buell had four divisions with a total of 35,000 men in Huntsville, and Ormsby Mitchel was nearby with 11,000 more. There was also George Morgan's division to the north in the Cumberland Gap that could come to Buell's assistance if need be, as well as a division under Major General George Thomas in the rear at Iuka, Mississippi, near the Tennessee-Alabama border. If push came to shove, two more divisions could be obtained from Grant in Memphis.

The appearance of Union strength was misleading. By that time, the last thing Buell wanted was more soldiers. The men and animals he already had on hand were on half-rations. His main supply route was a single rail line to Louisville that ran in a roundabout fashion through northern Alabama to Corinth, and then north through Tennessee into Kentucky. This route had been damaged during the Federal advance and was easily broken by Confederate raiders. Sniper fire was so common that armored boxcars had to be provided to protect train crews. To aggravate the difficulties, in late June Buell's staff had completely bungled the shipment of vital rations. Buell reported: "We are living from day to day on short supplies and our operations are completely crippled."

Then, on 8 July, Buell got more bad news. He received a telegram from Halleck that reported the Confederates were preparing to move against him. The message went on to state:

THE PRESIDENT TELEGRAPHS THAT YOUR PROGRESS IS NOT SATISFACTORY AND THAT YOU SHOULD MOVE MORE RAPIDLY. THE LONG TIME TAKEN BY YOU TO REACH CHATTANOOGA WILL ENABLE THE ENEMY TO ANTICIPATE YOU BY CONCENTRATING A LARGE FORCE TO MEET YOU. I COMMUNICATE HIS VIEWS, HOPING THAT YOUR MOVEMENTS HEREAFTER MAY BE SO RAPID AS TO REMOVE ALL CAUSE OF COMPLAINT, WHETHER WELL FOUNDED OR NOT.

Buell was so shocked and upset by this message that he refused to answer for three days, and responded only when he received a follow-up telegram:

I WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU. H.W. HALLECK.

Buell responded with a detailed explanation of his difficulties, and added:

THE DISSATISFACTION OF THE PRESIDENT PAINS ME EXCEEDINGLY.

Halleck replied on the next day, 12 July, demonstrating his odd habit of giving a subordinate a kick in the ass and then following it with a pat on the back. He assured Buell that he understood the problems, explained that the Administration's impatience was due to the fact that military failures in the East had worked them up "to a boiling heat," and promised to smooth matters over with the politicians.

* Buell had further troubles for the moment: Confederate Brigadier General John Hunt Morgan and his cavalrymen were raising hell in the Federal rear up in Kentucky. Morgan had left Knoxville on 4 July with orders from Major General Edmund Kirby Smith -- commander of the Confederate Army of East Tennessee -- to ride into Kentucky and disrupt the Federals there. Morgan was a Kentuckian by birth and breeding, very much the Kentucky gentleman, tall and with refined manners. His cavalry troopers demonstrated the flair and dash expected of their kind, with fancy clothes and gear and dapper beards. Among them was George Ellsworth, an expert telegrapher and wiretapper, whose skills proved particularly useful.

Morgan was a Kentuckian by birth and breeding, very much the Kentucky gentleman, tall and with refined manners. His cavalry troopers demonstrated the flair and dash expected of their kind, with fancy clothes and gear, along with dapper beards. Among them was George Ellsworth, an expert telegrapher and wiretapper, whose skills proved particularly useful.

It took the raiders three days to get out of the mountain territory, being persistently harassed by Unionist bushwhackers until they did. When they arrived at the town of Sparta, about a third of the way to Nashville, they found plenty of Confederate sympathizers who were eager to sign up. Not all of these men were interested in the glory of the thing: they were mountain men who had a long tradition of vendettas, and they were after revenge. One, Champ Ferguson, was picked up by Morgan as a guide, but had to be told not to murder Yankee prisoners. One of Morgan's men observed of Ferguson:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

Ill-treatment of his wife and daughter by some soldiers and Home-guards enlisted in his own neighborhood made him relentless in his hatred of all Union men. He had a brother of the same character as himself in the Union army, and they sought each other persistently, mutually bent on fratricide. The mountains of Kentucky and Tennessee were filled with such men, who murdered every prisoner they took.

END_QUOTE

Morgan rode north from Sparta to Tompkinsville, roughly in the middle of the Kentucky border with Tennessee, where he surrounded a Federal battalion and forced them to surrender. All the prisoners were paroled except for their commander, Major Thomas Jefferson Jordan. Jordan had earned a bad reputation by insulting and intimidating the women of one Kentucky town, and so he was packed off to prison in Richmond to reflect on the errors of his ways.

The raiders moved another 30 miles (48 kilometers) north, where Ellsworth tapped into the telegraph line from Nashville to Louisville. He sent reports over the wire of Morgan's force striking towards Louisville and Cincinnati, Ohio, with the bogus reports helping to spread confusion to the north. In reality, Morgan's troopers circled around north of Louisville to the banks of the Ohio, then rode back southeast to overrun a small garrison of green Union troops at Cynthiana, Kentucky, on 17 July. While Morgan and his men numbered only about a thousand and weren't really more than a painful nuisance, their unpredictability and mobility spread panic through Unionist circles in Kentucky and through the neighboring states. Lincoln sent an understated message to Halleck: "They are having a stampede in Kentucky. Please look to it." Halleck responded by mindlessly badgering Buell.

It was too late by then. Morgan was already on his way back to Tennessee after inflicting a considerable amount of damage in Kentucky, and would return safely to Tennessee on 28 July. He wired Smith, to tell him that if he were to march his army into Kentucky, "25,000 or 30,000 men would join you at once."

The truth was that only about 300 men had joined up with Morgan during the raid, and he had alarmed Unionist sympathizers in the region so much that they flocked to the recruiters. Over 7,000 men signed up with the Union in Kentucky alone. Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes, later a US president, was recruiting in Kentucky and proclaimed: "Hooray for Morgan!" Morgan had many virtues, but he also had a certain unfortunate tendency to believe what he wanted to believe, instead of facing reality.

* While the raid was in progress, it still helped bog down the Union movement on Chattanooga even further, but Buell received some good news, too. In early July, the Federal advance across northern Alabama reached the town of Stevenson in the northeast corner of the state, which connected to Nashville through a rail line going northwest through a place called Murfreesboro. That gave Buell a second, more direct line of supply that was not so easy to cut, and he sent a brigade to Murfreesboro under Brigadier General Thomas Turpin Crittenden to protect the rail line. The same day that Buell received Halleck's reassuring telegram, 12 July, he was also informed that supply trains would arrive from Nashville in a day or two, allowing him to take his men off half-rations.

Unfortunately, Buell had the black-magic touch: nothing good ever seemed to last for him. He was faced with a particular difficulty in the form of Confederate Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest -- a man with little military background, once a slave trader, but a hard fighter, a military genius, and arguably the Confederacy's best cavalry commander.

On 6 July, Forrest had left Chattanooga with a thousand troopers to harass the Federals in central Tennessee. They acquired reinforcements from scattered Confederate units in the area and arrived at the town of Woodbury, Tennessee, about 18 miles (29 kilometers) east of Murfreesboro, on 12 July. The locals were glad to see Forrest and his troopers. The Federals had moved into the town the evening before, arrested most of the men as Confederate sympathizers, and intended to hang six of them on the morning of 13 July. Forrest promised to stop the executions, and he was as good as his word.

That morning Forrest and his men swept into Murfreesboro, taking the Yankees completely by surprise. The raiders attacked Crittenden's scattered forces, while a column on horseback melodramatically charged into town to rescue the condemned men. The Union jailers wanted to shoot the prisoners in their cells instead of seeing them liberated, but the rebels were on them too fast. A jailer set the building on fire and fled with the keys; the rescuers were barely able to pry open an iron door and get the men out safely. In the meantime, another group of Confederates had seized the town's hotel, along with General Crittenden and his staff. By noon, it was all over. The Federals had put up a fight in some places, but Forrest managed to cow the entire brigade into surrendering. He captured about a half-million dollars worth of stores, and then thoroughly wrecked the railroad depot.

Buell was outraged, calling the surrender of Crittenden's brigade one of the most "disgraceful examples of neglect of duty", and added that it "fully merits the extreme penalty for such disconduct." Crittenden would be returned on a prisoner exchange some months later, but his military career was finished, and he would resign.

In any case, Buell hurried a division under Brigadier General William "Bull" Nelson -- a big gorilla of a man, a US Navy officer shifted to the US Army -- up the railroad line to chase after Forrest, but the rebel cavalry disappeared back towards the mountains. They re-appeared again on 21 July, burning three bridges near Nashville and frightening the Yankees there into believing they would soon be swept up as well. Nelson marched his men north from Murfreesboro to intercept the rebels, but Forrest took his men on a side road and quietly listened to the Federals tramp past.

Buell set his work gangs to repairing the damage, and they did it swiftly. By 29 July, they had the line to Nashville working and trains began to arrive in Stevenson bearing carloads of rations. Buell's men went off half-rations and got new shoes -- but all things considered, that was too little to make them happy. If Lincoln suspected Buell was taking his time, Buell's men were sure of it. One of his officers called it "holiday soldiering", and the soldiers in general regarded their commander with contempt. Buell was methodical to a fault, and nothing anybody could do would hurry him along.

Buell also had little concept of leadership. He was a disciplinarian who had no ability to inspire his men and no interest in doing so, a sour fellow who tended to give criticism instead of praise. He earned no favors with his soldiers with his severity.

Before Buell's arrival, Mitchel's men had been becoming increasingly disorderly, and Mitchel had complained to Secretary Stanton that "the most terrible outrages -- robberies, rapes, arsons, and plunderings -- are being committed by lawless vagabonds connected with the army." The violence done by Mitchel's men had been greatly aggravated by attacks by Confederate guerrillas, which predictably led to escalation of Federal reprisals.

For example, Colonel John Beatty of the 3rd Ohio Infantry was bringing his men down to Huntsville by train in May when they were ambushed near the town of Paint Rock. He stopped the train, went into the town, assembled the citizens, told them with threats of hangings that the bushwhacking would damn well cease -- and then torched the place to show he meant business. Another colonel, John Basil Turchin, in command of Illinois troops, took his men into Athens, Alabama, in response to another guerrilla attack. Turchin, who had once been an officer in the Russian Tsar's army, told his men: "I shut mine eyes for one hour." The men had a party, robbing the residents of their jewelry and silver, trashing things as they pleased, raping slave girls.

Buell would have none of such disorderliness. When he arrived in Huntsville and learned of the incident in Athens, he was shocked that "not only straggling individuals, but a whole brigade, under the open authority of its commander, could engage in these acts." He had Turchin court-martialed and drummed out of the service. Restraint in dealing with the civilian population was not an unusual policy at the time -- Sherman, a much more popular leader, was at least for the moment more severe in this discipline than Buell -- but Buell's cold, sour leadership gave him no saving graces. Colonel Beatty, who was involved in Turchin's court-martial, wrote in his diary:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

Turchin has gone to one extreme, but Buell is inaugurating the dancing-master policy: "By your leave, my dear sir, we will have a fight; that is, if you are sufficiently fortified. No hurry; take your own time." To the bushwhacker: "Am sorry you gentlemen fire at our trains from behind stumps, logs, and ditches. Had you not better cease this sort of warfare?"

END_QUOTE

Turchin's wife later appealed to the President; the Russian colonel not only found himself re-instated, but promoted to brigadier general. Lincoln's patience with polite warfare had run out long before. Incidentally, Ormsby Mitchel was recalled to Washington in early July to explain illegal cotton transactions in his department -- the cotton trade, having been interrupted by the war, was proving a deep source of corruption. He survived this interrogation well enough to be promoted to major general, to be sent to the South Carolina coast, where he would die of yellow fever in the fall. In any case, Buell's army was going nowhere, and he didn't seem like the kind of general who could take it anywhere.

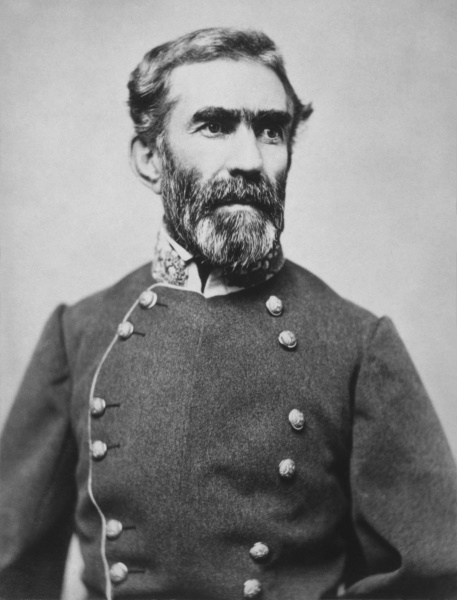

BACK_TO_TOP* If Buell wasn't willing to move, no such hesitation afflicted General Braxton Bragg -- commander of the Confederate Army of the Mississippi, having taken command in late June when Beauregard left for health reasons. Bragg was feeling aggressive, even though the resources available to Bragg were far inferior to those of his adversary.

Bragg, on taking command, found that many of his men were on the sick list, and large numbers of them had been sent elsewhere to deal with other Federal threats. Bragg was determined to make the best use of what he had and began an energetic program to whip his army into shape. His efforts highlighted both his virtues and his defects.

While Buell was colorless, Bragg was simply unpleasant. Grant had known Bragg during the war with Mexico in the 1840s, and described him as "remarkably intelligent and well-informed", as well as "thoroughly upright" -- but "naturally disputatious", willing to quarrel fiercely with his superiors and harass his subordinates for the "slightest neglect" of his "most trivial order". Much of this was apparently due to persistent headaches and chronic indigestion, but Bragg demonstrated little inclination to keep his bad disposition on a leash.

There was a story from the old Army that Grant was fond of in which Bragg, a young lieutenant, was assigned the dual roles of company commander and quartermaster. He submitted requisitions as company commander to himself as quartermaster and then denied them; challenged the denial; rejected the challenge; and finally took the dispute to the post commander, who replied: "My God, Mr. Bragg, you have quarreled with every officer in the army, and now you are quarreling with yourself!" That was far-fetched, but a more likely story claimed that during the Mexican War, one of his Bragg's men had lit a shell and rolled it under Bragg's cot while he lay sleeping. The shell was defective; Bragg was shaken by the blast, but unharmed.

Braxton Bragg could not hope and did not care to be liked, but if he could deliver victories, that would not matter at all. At first, it seemed to his soldiers that he might just be the man who could do it. He imposed harsh discipline: not only did he drill his men incessantly, but desertions and other serious crimes were dealt with by firing squads, with the execution of the offender witnessed by all his comrades. Lesser crimes were dealt with by brandings and savage floggings. To his credit, Bragg believed in carrots as well as sticks, and provided better rations and new uniforms. On one hand, Bragg demonstrated that he meant business, and on the other he showed the ability to carry it out. The healthier camp at Tupelo, Mississippi, had brought many of his soldiers off the sick list, and in general their morale improved. Probably having a commander they could all hate improved their solidarity as well.

By 12 July, he was able to report to the Confederate government in Richmond, Virginia, that his army's "condition for service" was good. He was ready to take the offensive. Morgan and Forrest were providing an inspiring example for Confederates throughout the West who wanted to take on the Yankees, and in mid-July Bragg dispatched two brigades of cavalry to harass Buell's supply lines in northern Alabama and western Tennessee. On 22 July, Bragg wrote Beauregard, who was then in recuperation: "Our cavalry is paving the way for me in Middle Tennessee and Kentucky."

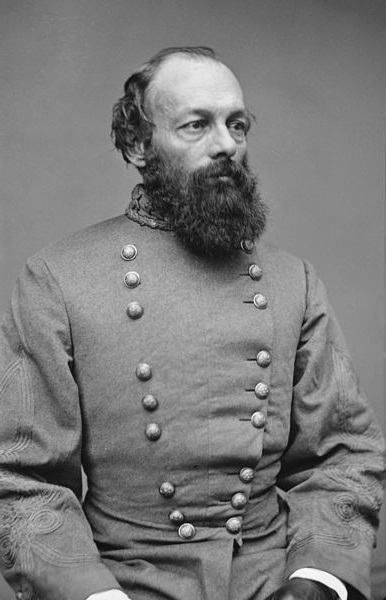

* Bragg intended to move. Edmund Kirby Smith, in command of Confederate forces in Knoxville, had been growing increasingly nervous about the buildup of Federal forces around him. Smith had been wiring Bragg and everyone else in authority with frantic appeals for help. There was little response to his pleas until 21 July, when Bragg wired Richmond:

WILL MOVE IMMEDIATELY TO CHATTANOOGA IN FORCE AND ADVANCE FROM THERE.

On 24 July, Bragg began his move. He left Major General Sterling Price in command of 16,000 men in Tupelo to help protect northern Mississippi, and sent engineers and horse-drawn elements west from Tupelo across Alabama. Four infantry divisions, over 30,000 men, were then sent by rail. Their route was a remarkably roundabout one, due to the fragility of the Southern rail system and the intrusions of the Yankees, with the men sent all the way south to Mobile on the Gulf Coast and then back north to Chattanooga.

The rail movement went very smoothly, a tribute to Bragg's organizational skills. He arrived himself in Chattanooga on 30 July. Smith, who had not been informed of Bragg's move, finally got word of it and came down from Knoxville to meet with Bragg the next day. Smith was enthusiastic about the prospects for dealing a blow to the Yankees with their combined Confederate force of over 50,000 men.

Braxton Bragg had not only acted energetically; he had demonstrated strategic insight in recognizing the railways as a key to military operations. By attacking Buell's rail connections and exploiting his own, he hoped to level the imbalance between his forces and the enemy's.

* After re-opening his supply line from northern Alabama back to Nashville, Buell resumed his methodical offensive towards Chattanooga, attempting to build up a forward supply base at Stevenson, Alabama, and build a 1,400-yard (1,280-meter) long pontoon bridge across the Tennessee River at Bridgeport. By that time, Buell had details of Bragg's shift to Chattanooga. While Buell had over 45,000 men, a third of those were guarding his supply line and the remainder hardly seemed like enough to deal with Bragg. Buell still felt confident; he had, as mentioned, been promised two divisions from Grant if he should feel they were needed, and believed that he had access to forces adequate to deal with the Confederate incursion.

When Halleck wired him on 6 August, indicating that there was "great dissatisfaction here at the slow movement of your army towards Chattanooga", Buell responded immediately that he understood the reasons for anxiety, but he had "not been idle or indifferent." The next day he level-headedly described the reports of 60,000 rebels confronting him as "exaggerated", and proposed to march on Chattanooga "at the earliest possible day", adding that if he attacked the enemy "I do not doubt we will defeat him."

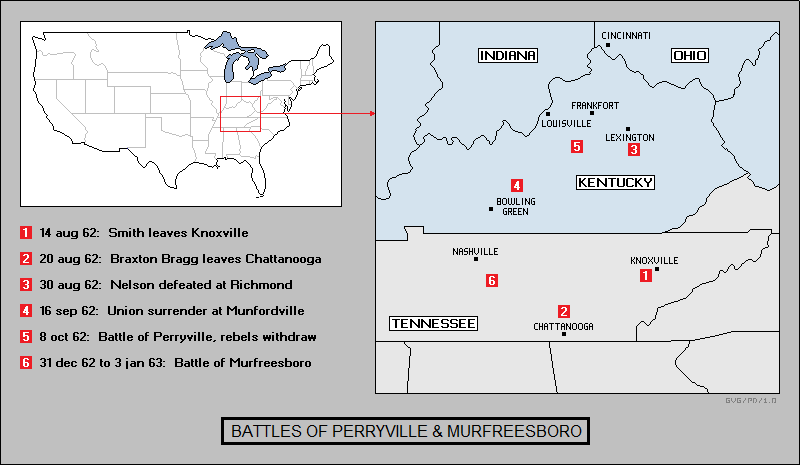

The enemy had other ideas. On 12 August, John Morgan and his troopers destroyed a vital 800-foot (245-meter) long railroad tunnel at Gallatin, north of Nashville, by pushing burning boxcars down its length, where they incinerated the supports. Re-opening the tunnel would be difficult, and the low levels of the rivers of the region continued to make supply by water impossible. This disaster was followed by news that on 14 August, Edmund Kirby Smith had left Knoxville with 14,000 men to move towards the Cumberland Gap and into Kentucky. On the 16th, Buell dispatched William Nelson and a group of officers to Kentucky to work with local Unionists and organize a defense of the state, and called for the two divisions of Grant's that had been promised.

Dissatisfaction with Buell was reaching the snapping point in Washington. On 18 August, Halleck sent a wire informing Buell in an oblique way that he would be sacked if more action were not forthcoming. Buell called his bluff, replying that "if the dissatisfaction cannot cease on grounds which I think might be supposed if not apparent, I respectfully request that I be relieved" and that his position was "far too important to be occupied by any officer on sufferance."

Being relieved of duty turned out to be the least of Buell's immediate worries. The next morning, he learned that Bragg's army was massing near Chattanooga for the offensive. Buell had told Halleck he looked forward to this prospect, but now that it was an imminent reality, he had second thoughts; he moved his command north up his supply line into middle Tennessee to the vicinity of Murfreesboro.

On 23 August, Buell learned the full scale of Bragg's forces. There were fifty regiments, he was told, and they were well-armed, with plenty of artillery. He concluded that there was no choice but to dig in and prepare a defense. The two divisions that Grant sent him were redirected towards Nashville on forced marches, and the supply depot at Stevenson was ordered cleaned out. What could not be saved was to be burned, as was the recently-completed pontoon bridge at Bridgeport on which much effort had been spent.

The effect of this flurry of action on Buell's already discouraged troops was to make them even more discouraged. On receiving the order to pull out, one division commander muttered: "Don Carlos won't do; he won't do." By the end of August, the withdrawal was complete, with the army in a state of demoralization and confusion. An observer commented that "nobody knows anything, except that the water is bad, whiskey scarce, dust abundant, and the air loaded with the scent and melody of a thousand mules."

* For at least once in his life, Braxton Bragg was happy, and he had good reason to be. The Federal drive into the Confederacy had stalled in almost every theater. With Buell retreating and on the defensive, Bragg saw an opportunity to turn the tables on the Yankees.

Bragg had discussed what might be done in the theater with Smith at the beginning of August. There were two sizeable Union forces in the area: Buell's, consisting of about 30,000 men, at the time in central Tennessee and northern Alabama; and George Morgan's, with about 9,000 men at the Cumberland Gap. Bragg's plan was for Smith to destroy Morgan, and then Bragg and Smith would fall on Buell. That done, the Confederate armies would mop up the Yankees in central Tennessee, and then march into Kentucky. Morgan's cheery reports had led Bragg to believe that the populace would rise in support of their Confederate liberators and throw out the Unionists.

Smith had gone back to Chattanooga with Bragg believing that the two had an agreement, but while Confederate President Jefferson Davis was enthusiastic about the plans of the two generals, Davis surprisingly failed to recognize the need for coordination between them. The two men answered only to Davis, and each could do as he pleased.

Edmund Kirby Smith was a single-minded man, and had every intention of doing what he pleased. He had a hidden agenda, well concealed by a quiet and polite demeanor, and was intent on pursuing it. Smith really wanted to march into Kentucky; he used his "agreement" as a lever to pry two brigades from Bragg, including one under Brigadier General Pat Cleburne -- an immigrant from Ireland who had been a lawyer in Helena, Arkansas before the war broke out. Although Cleburne had no formal qualifications as an officer, he was correctly recognized as an asset to the Confederate cause.

The loss of the two brigades left Bragg short-handed, but he managed to scrape up reinforcements of his own from Van Dorn and extended an invitation to John C. Breckinridge, still under Van Dorn, to take command of a Confederate Kentucky division. Breckinridge was eager to fight at the head of troops from his native state, and immediately accepted. Bragg hoped that Breckinridge's presence would help draw Kentucky volunteers to the rebel cause, though as it would turn out Breckinridge would arrive much too late to figure in Bragg's offensive plans. Bragg had for similar reasons put Kentuckian Simon Boliver Buckner -- exchanged in July after being captured at Fort Donelson, to then be promoted to major general -- in charge of another division.

* In any case, Smith made his move out of Knoxville on 14 August with 21,000 men without any real planning with Bragg. George Morgan's forces in the Cumberland Gap proved too well dug in to root out, so Smith left about 9,000 of his own men to keep an eye on them while the rest set off in the direction of Lexington, Kentucky.

Smith had expected to fill his ranks with Kentucky volunteers -- but, as in eastern Tennessee, eastern Kentucky was strongly Unionist. On the 24th he sent a message to Bragg, saying: "Thus far the people are universally hostile to our cause." Smith was, however, confident that more enthusiasm would be apparent once he got out of the harsh and hostile mountain regions.

The locals found the invaders unimpressive, "ragged, greasy, and dirty"; they "surrounded our wells like the locusts of Egypt" and begged for bread "like hungry wolves". Fortunately, despite being heavily armed, the rebels refrained from simply taking whatever they wanted, and "appeared exceedingly grateful" for whatever charity they received. No doubt the charity of the locals was enhanced by their realization that the invaders might not be so polite if charity wasn't forthcoming -- though Smith had been very specific that they were to conduct themselves with "the most perfect decorum of conduct towards the citizens and their property", so they would not antagonize the people Smith hoped would come to their ranks.

Smith sent a message to Bragg on 24 August to ask him to move north into Kentucky to support his own offensive. The "agreement" between the two men having come to nothing, Bragg adjusted his own plans to operate in support of Smith, and on the 28th he launched his own army of 30,000 men northward across the Tennessee River at Chattanooga in order to keep Buell from falling on Smith and wiping him out.

On 29 August, Smith's column climbed up Big Hill, at the edge of the mountain barrens, where the Bluegrass country lay before them like the Promised Land. That evening, Smith's cavalry encountered Federal soldiers slightly to the north at a small town named Rogersville and were driven back after a short skirmish, which was ended by nightfall. Smith was actually pleased by this development, since it meant that the Federals were going to engage him in open country. If they chose instead to make a stand on the bluffs along the banks of the Kentucky River farther to the north, they would be much harder to deal with.

Smith told his men to sleep with their weapons in line of combat, ready to take the offensive at first light. There were about 7,000 Federals in front of them, also sleeping with their guns. They were very green Ohio and Indiana volunteers under the command of William Nelson, and had been sent to battle in haste by the governors of their states in response to an urgent plea for help from Washington.

Nelson was actually in Lexington, still farther north above the Kentucky River, when Smith's men made contact. Nelson got the news in the small hours of the morning of 30 August, and it wasn't welcome. The Union force was totally inexperienced; the green soldiers didn't stand a chance in a fight against an experienced enemy force in open country. Nelson got dressed and immediately rode off to the battlefield, hearing the sounds of battle just after he got south of the Kentucky River. He had to take a roundabout route in order to avoid rebel cavalry, and it was noon before he arrived, just south of the town of Richmond, Kentucky, where he found his forces "in disorganized retreat or rather rout." They had fought well enough at first, but focused Confederate attacks were wearing them down, and they were on the verge of complete collapse.

He managed to rally them on the edge of town, using the rock walls and tombstones of a cemetery as a line of defense. Once the men were in place he walked his huge frame up and down the line in front of them to encourage them, shouting: "If they can't hit me, they can't hit anything!" They hit him twice. Both wounds were minor but painful, and he received them without benefit, for the men immediately crumbled under attack and fled, only to run into the artillery of cavalry detachments that Smith had sent around to catch them. The Yankees threw down their arms and threw up their hands. Nelson was captured, but quickly escaped.

Much of the credit for the victory belonged to Pat Cleburne, now a brigadier general, who directed assaults that rolled over the Federals every time they tried to make a stand. He wasn't on hand for mopping up, however, since a bullet had struck him in the cheek, knocked out the teeth behind it, and gone out his open mouth. It was a spectacular Confederate victory. The Federals lost about 1,000 killed and wounded, plus over 4,000 captured, along with a large amount of supplies, weapons including nine artillery pieces, and ammunition. The rebels lost about 450 killed and wounded out of the 7,000 fighters they had actually fielded.

Bragg was in high spirits. On 27 August, he had written Sterling Price back in Tupelo, saying in a burst of grand confidence that he would have "Buell pretty well disposed of." Bragg suggested that Price would do as well against Union forces arrayed against him, and concluded that "we confidently expect to meet you on the Ohio and there open the way to Missouri." Despite the confusion in the campaign so far, things had gone well. Bragg had every good reason to think he might gain the upper hand in the war in the West, and help assure complete Confederate victory.

* After defeating William Nelson and his green Union troops at Richmond, Kentucky, Edmund Kirby Smith and his men moved in an arc curving northwest through eastern Kentucky. They occupied Lexington on 2 September, and Smith set up his headquarters there. His cavalry moved into Frankfort, the state capitol, the day after the governor and the legislature prudently made a hasty exit to Louisville. Louisville was on the Ohio River and was the continuation of that arc, making it the logical next target for the rebels, though it was just as plausible that they could strike directly north from Lexington to Cincinnati, Ohio.

While crowds had cheered the rebels as they marched into Lexington, the ranks of Kentuckians that Smith had expected to fall in with his army were not materializing. Some of the citizens of the city made no secret of their dislike for the Confederates. When a pretty 17-year-old girl named Ella Bishop saw the American flag being dragged through the streets by rebel soldiers, she ran out, grabbed it, wrapped it around her, and said she would surrender it only with her life; they wouldn't lay a hand on her.

Unfortunately, Buell was not as bold or brave as Ella Bishop. While his forces in central Tennessee were in a position to strike quickly at Braxton Bragg's columns marching north, Buell was confused by events and demoralized. He did not attack. Bragg's forces continued their northward advance unhindered. They were warmly greeted by Kentuckians, who cheered them and gave them food and drink. Bragg was pleased by events. He had managed to derail the Federal drive across northern Alabama towards Chattanooga.

The arrival of George Thomas, sent from Grant with two divisions, stiffened Buell's spine. Furthermore, Bragg's northward advance threatened the Union supply center at Bowling Green, Kentucky, and he had to protect it. Buell wired Halleck that he intended to move against the enemy. Halleck replied:

GO WHERE YOU PLEASE, PROVIDED YOU FIND THE ENEMY AND FIGHT HIM.

On 7 September, Buell set out northward with five divisions in parallel to Bragg's march, leaving George Thomas to hold Nashville with the three remaining divisions. Buell reached Bowling Green on 14 September.

Bragg had moved into the town of Glasgow, 30 miles (48 kilometers) to the east, where he was between Buell and Smith and could move in support of Smith in an offensive towards Louisville. Louisville was a major supply center for the Union army, and Confederate capture of a major city on the Ohio would spread shock through the Union and hopefully encourage the recruiting that had proven sluggish so far.

* Bragg's men had seen almost no fighting during the campaign to that point, but it was certain that violent collisions would occur in time. On 13 September, while his army was moving into Glasgow, Bragg had sent a Mississippi brigade under Brigadier General James R. Chalmers 10 miles (16 kilometers) north to cut the rail line over the Green River at Cave City.

That was easily done, but then Chalmers linked up with some of Smith's far-ranging cavalry detachments who wanted help in attacking a Federal outpost at the nearby town of Munfordville. Chalmers agreed without consulting headquarters. The next morning, 14 September, Chalmers attacked, thinking there were only a handful of Yankees in front of him. Instead, he ran directly into the teeth of a brigade-sized force of 4,000 Indiana volunteers under Colonel John T. Wilder and took a nasty bloodying, losing almost 300 men, over four times more than the Federals.

Chalmers hadn't expecting it. He sent Wilder a message complimenting him and his men on their "gallant defense" but indicated that with Bragg's army nearby their position was hopeless, and demanded unconditional surrender "to avoid further bloodshed." Wilder responded: "Thank you for your compliments. If you wish to avoid further bloodshed keep out of the range of my guns."

Chalmers pulled out and reported the incident to Braxton Bragg the morning after that, 15 September, stating his "fear that I may have incurred censure at headquarters by my action in this matter." That was an understatement. Bragg, never particularly good-natured, was angry that Chalmers had acted without consulting him, and furious at the defeat. Bragg sent all four of his divisions to Munfordville that same day, two of them under Lieutenant General William J. Hardee to approach the Federal garrison from the south and two under Major General Leonidas Polk to circle around and approach from the north. There was to be no repetition of the humiliation of 14 September.

By mid-afternoon on 16 September, the Confederates had sealed off Wilder's men and had fired a few shots to establish range. Bragg sent a message to Wilder, stating that the Federals were surrounded by overwhelming force and were to unconditionally surrender immediately. Wilder was skeptical and responded to Bragg with the question. What proof did Bragg have that he in fact had such a great force around him? Bragg replied that he would provide proof when he attacked, and gave Wilder a one-hour deadline.

Wilder's reaction to this was unconventional. He walked to the Confederate lines under a flag of truce and asked to speak to Major General Simon Bolivar Buckner, who commanded one Hardee's divisions. Once there, Wilder explained that Buckner had been recommended to him as a man of honor, and wanted his advice. Was it his duty to surrender, or fight it out? Wilder wasn't a professional soldier, after all. 13 months before he had been an Indiana industrialist and knew little of military matters.

Buckner was flabbergasted. As naive as this action might have seemed, Buckner actually was a man of honor, and he later said that he "would not have deceived that man under those circumstances for anything." After some awkward discussion, Buckner sensibly decided the best thing to do was simply give Wilder a tour of the rebel positions and let the Yankee make up his mind for himself. Wilder accepted, and the two men made their inspection in the dark. It was after midnight; Bragg's time limit had expired, but there was no sense in fighting until daylight. After counting 46 guns on the south side of his position alone, Wilder sadly concluded: "I believe I'll surrender."

The next morning, the Yankees walked out their position on parole. The officers were allowed to keep their swords and sidearms. Bragg was pleased: he had captured a large quantity of weapons, including ten guns, as well as ammunition, supplies, and a number of horses and mules. He gave his men a day's rest. The rebels had not seen the last of John T. Wilder, however.

BACK_TO_TOP