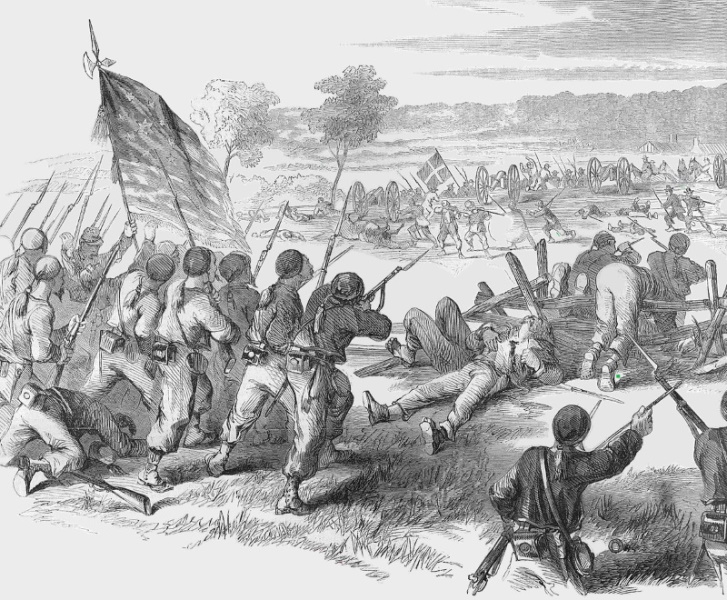

* The battle at Antietam Creek jumped off with a Union assault on the northern end of the Confederate line at sunrise. After hours of vicious but inconclusive fighting, the struggle shifted to the center, with a similar result; and then to the south, with the Confederate defense surviving by the hardest. By evening, the two armies remained in a stand-off, with bodies carpeting the battlefield.

* Union troops waited for the morning of Wednesday, 17 September, to arrive, and the battle over the far side of the Antietam to begin. As with many of his men, General Joe Hooker couldn't sleep. Sometime before sunrise he got up and rode down toward the picket line to survey the field over which he would lead the assault.

Light was dawning over the scene. The rain had stopped, leaving a thin ground fog, but Hooker could still see his objective: the high ground about a mile away, lined with four batteries of rebel artillery under the command of Colonel Stephen D. Lee, marked by a little white building that many of the Federals thought was a schoolhouse but in reality was the Dunker Church. The attack would be directed roughly towards this structure, through Miller's Farm and Cornfield, bracketed by the East Wood and the West Wood. Hooker had three divisions totaling roughly 9,000 men. Facing them was Stonewall Jackson's command, also made up of three divisions but with about a thousand fewer men, holding a rough line in fair defensive positions through the objective area.

Hooker moved his men out at about 5:30 AM, with Abner Doubleday's division, inherited from the wounded John Hatch, on the right; George Meade's Pennsylvania division in the center; and Brigadier General James Rickett's division, with a brigade of Meade's in the lead, on the left. Confederate pickets started taking shots at the advancing Federals, and Union skirmishers returned fire. Cannon shot and shell started to sail through the morning mist.

Doubleday's division came under accurate and deadly artillery fire from a battery run by Jeb Stuart, sited on a hill on a farm owned by a Mr. Jacob Nicodemus off the battlefield to the west, and Colonel Lee's artillery near the Dunker Church. Hooker's batteries, sitting on a ridge on the Poffenberger Farm, responded, and then the 24 Union 20-pound (9.1-kilogram) Parrott guns, firing at long range about two miles (3.2 kilometers) east of Antietam Creek, joined in the fight. In moments, the firing rose to a "prolonged roar".

Meade's men moved to the northern edge of the Cornfield and came under artillery fire. Hooker had artillery brought to the Miller Farm and started plastering the rebels defending the Cornfield, knocking them down in rows, cutting down cornstalks over the field, as Hooker put it later, "as closely as could have been done with a knife."

Rickett's division got through to the southern side of the East Wood and ran into resistance from Confederates fighting from a farm owned by a Mr. Samuel Munma, resulting in a nasty fight and many men shot down on both sides. One of Rickett's brigades emerged from the East Wood into the Cornfield to encounter a Georgia brigade, and the two sides started firing away at each other through the black powder smoke at 200 yards (180 meters) range.

Reinforcements came up for both sides, a brigade of Meade's on the Union side, Jackson's "Louisiana Tigers" on the other, and the fight rose to a fury. A Massachusetts man wrote of it later: "Rifles are shot to pieces in the hands of the soldiers, canteens and haversacks are riddled with bullets, the dead and wounded go down in scores." The 12th Massachusetts lost about two-thirds of its men.

The rebels pushed the Yankees back, but the Federals rolled a battery directly onto the Cornfield and tore into the Confederates with shot, shell, and canister, repulsing the counterattack. The Louisiana Tigers lost over 300 of their 500 men. By that time, it was after 7:00 AM and the battle in the Cornfield was stalemated, having resulted in nothing more than a ghastly number of killed and wounded on both sides.

* In the meantime, John Gibbon and his Iron Brigade, in the lead of Doubleday's division, had been making progress along the Hagerstown Turnpike, in the front bounded by the West Woods and the Cornfield. They ran into a regiment of Confederates that popped up from the tall grass and threw a volley into them, but the Federals fought back energetically and advanced. Then, about 15 minutes later, at 6:45 AM, two fresh rebel brigades under Brigadier General William E. Starke materialized out of the West Woods and took up a position on the rail fence along the turnpike, firing into the Federals, only a stone's throw away across the road.

This action was more courageous than wise. The Yankees wheeled about to fire back; two of Gibbon's regiments that had been advancing through the West Woods came up to fire down the rebels' flank; and Gibbon's artillery, set up in farmer Miller's barnyard, raked them with canister and shells. In 15 minutes, the Confederate dead were piled on the ground and left dangling over the splintered rail fence. The survivors fell back to the woods. Starke was hit three times, and died shortly thereafter.

The Union soldiers had cracked the Confederate line, and the Dunker Church was only a few hundred yards away. If they took that, they would seize the high ground and sweep away the rebel batteries that were backing up the defense; they rushed forward "loading and firing with demoniacal fury, and shouting and laughing hysterically."

They were then suddenly confronted by a screaming line of Confederates rushing them in turn from in front of the church. Hood's Texans had just about been ready to eat the hot meal their commander had obtained for them when they were ordered to move up in support of Jackson's wavering defense. The Texans were enraged at the interruption and fired a volley that cut "like a scythe" through the Union line, shattering the Federal attack and sending the survivors scattered back through the Cornfield.

Supported by other Confederate units, the Texans fanned out through the Cornfield. Two of Meade's brigades counterattacked, but the rebels sent them flying back as well, until they were inspired by a young private who stood there shouting: "Rally, boys, rally! Die like men! Don't run like dogs!" One of Meade's brigades did rally and lay down behind a rail fence, hidden in the black-powder smoke. When the Texans got close enough so that the Yankees could see their legs, they fired and cut the Confederates down.

Gibbon's artillerymen in the Miller barnyard fought like madmen, even though the rebels got to within yards of their muzzles. The gunners fired double-shotted canister loads at point-blank range, assisted by General Gibbon himself, who shouted: "Give 'em hell, boys!" They did, driving off three charges -- but then ran low on ammunition. At about 7:30 AM, Gibbon ordered them to withdraw, and they managed to scrape up enough live horses to pull back. The survivors of the Iron Brigade followed.

Hood had broken I Corps' attack. Hooker had lost about 2,500 men, and at least that many had evaporated to the rear, desperately trying to escape a fight that had become more than they could bear. Hood would be promoted to major general and there was no thought of pursuing the matter of his arrest, but the cost was the effective destruction of his command. Now he discovered that Mansfield was moving his XII Corps onto the field.

* Mansfield had never actually held a combat command before. He did his best to inspire his troops, riding up and down their ranks with his hat off, his white hair and beard streaming in the breeze. His men in fact thought much of him, one describing him as: "A calm and dignified old gentleman." Mansfield shouted as he rode past them: "Boys, we're going to lick them today!" They cheered him, and he shouted back: "That's right, boys, cheer! We're going to whip them today!"

He led his corps forward in a dense column to help complete the Federal victory he thought was taking place in front of him. As he approached the East Wood, Mansfield got a rude shock when Joe Hooker rode up to him and shouted: "The enemy are breaking through my lines! You must hold this wood!" -- and then rode off. Hooker had not coordinated his initial assault with Mansfield, and now felt he was in desperate need of his help.

By that time, the East Wood was full of the dying and dead, and Mansfield's clumsy column was coming under fire. He rode among them to get them into fighting formation, somewhat in confusion, suddenly shouting to one group of men shooting at indistinct forms in the woods: "You are firing at our own men!" A soldier shouted back: "Those are rebels, general!" Mansfield looked more closely and answered: "Yes, you are right!" -- and then his horse was shot. He dismounted and tried to clamber over a fence in front of him, only to take a bullet in his stomach. A few men formed up a detail and carried him back to an aid station on a litter of rifles, where a clumsy surgeon choked him with a shot of whiskey. He faded and died.

Tragic as this was, the death of a general was almost unnoticed in the chaos. Brigadier General Alpheus S. Williams took over to carry on the fight. Although he wasn't regular army, having been a judge and a postmaster of Detroit, Williams was a good fighting man who was known affectionately by his men as "Pop". Williams, the stub of an unlit cigar clenched in his teeth, moved his men forward into the Cornfield to make yet another assault. Hood's Texans, reduced to a shadow of their original strength, had been bolstered by three of D.H. Hill's brigades and the seesaw stand-off continued. The dead and wounded littered the field, leaving a scene that reminded one Federal of "burnt-out slag". The noise was "beyond anything conceivable," as General Williams said later.

D.H. Hill's other two brigades moved into the East Woods to support the fight and quickly found themselves in trouble. Among them was Samuel Garland's brigade of North Carolinans, who had been roughly handled at South Mountain and were shaken by the loss of their leader. When a Federal division fell on them the rebels broke and ran; the Yankees, under the command of Brigadier General George Greene -- a descendant of Revolutionary War hero Nathaniel Greene -- swept through the East Woods and the adjoining side of the Cornfield, where their flank assault left Confederate bodies "piled upon and across each other."

Their attack carried them through the stunned remnants of Hood's division. The Union men drove off Stephen Lee's battery from the high ground near the Dunker Church, while other Federals reached the church itself, finding a handful of bleeding Confederates resting in its pews. The Federals did not have the numbers to go further. The Yankees had gained nothing by capturing the Dunker Church. If the rebels were smashed and scattered by the battle, so were the Federals. Hooker had been shot in the foot and had lost a good deal of blood, so there was no one left to rally the Union men for the drive that would finish the Confederates off.

It was 9:00 AM. The firing fell off. The attacks of the Union II Corps and XII Corps had ended, with more than 8,000 Federals and Confederates strewn lifeless or maimed over the battleground. Someone asked Hood later where his command was. He replied: "Dead on the field."

* Lee had been busy behind the firing, shuttling reinforcements to help blunt the Yankee drive and herding the misdirected back into the fight. One soldier who had the bad judgement to think this was a good time to kill a pig and cook it was personally apprehended by an enraged Lee, who had the soldier escorted back to Stonewall Jackson with orders that the man be shot. Jackson, thinking there were more useful ways to expend the man's life, sent the fellow into the thick of the fighting in the West Woods, where he distinguished himself and still survived the fight. One rebel officer credited the soldier with "losing his pig but saving his bacon."

McClellan, in contrast to Lee, remained well to the west of Antietam Creek at his headquarters in a two-story brick house owned by a Mr. Philip Pry. The Pry House was on a knoll and gave a good view of the northern parts of the battlefield. McClellan had set up telescopes on stakes to observe the fighting, but the distance and black-powder smoke left him out of touch and out of control.

Major General Sumner, in charge of II Corps in the Federal center, had been chafing under delays since before sunrise, impatient at sending in men "in driblets", as he put it. He did not finally get his corps into action until almost 9:00 AM, after Hooker and Mansfield had spent their attacks. Sumner planned to advance his two divisions, under Major General John Sedgwick and Brigadier General William French, straight across the Antietam into the battlefield at the south of the East Wood, push through around the Dunker Church to the West Wood, and turn south to roll up the Confederates, driving them through Sharpsburg.

Sumner was aggressive, but inflexible. While he was moving up to the fight he ran into Hooker, who was too weak with the loss of blood to talk to him, and Alpheus Williams, who tried to tell him that surviving units from I and XII Corps were available to help in the drive. Unfortunately, Sumner was in a hurry, and didn't spare the time to listen.

Sumner personally led Sedgwick's division through the East Wood, which was ominously full of dead, wounded, and far too many able-bodied "good Samaritans" helping the injured and themselves off the field. He was over the Cornfield so fast that French's division lost track of them. When French got onto the battlefield 20 minutes behind them, he had no idea where they were, and turned southward below Greene's men at the Dunker Church.

Sumner was now advancing with only half his men. Worse, much to the concern of everyone from the brigade commanders on down to the privates, Sumner had the troops tightly organized in marching order, and had no skirmishers or flankers advancing outside his formation to detect possible traps. It was an invitation to disaster, one soldier writing later: "We were as easy to hit as the town of Sharpsburg."

A little after 9:00 AM, Sumner's advance brigade cut through the northern part of the West Woods and emerged onto a field, where they ran into a handful of stubborn Confederates and got into a firefight. The other two brigades came up into the West Woods, where they couldn't fire on the rebels without hitting their own men. The advance halted while the lead brigade cleared out the opposition. Sumner's men were taken completely unaware when a storm of fire tore into their ranks from the south: by chance, Sumner's division had happened to cross the path of advance of Confederate reinforcements moving up to protect Lee's northern flank. These troops consisted of two divisions under Generals Walker and McLaws, and a brigade under Colonel George "Tige" Anderson -- along with one of Jackson's brigades under Brigadier General Jubal Early that had managed to survive the earlier onslaught and form up with remnants of shattered units.

The rebels poured fire into the Yankees from the west and south, sweeping them down and spreading panic through their ranks. The Federals were so tightly packed that they couldn't maneuver and were a hideously convenient target. Brigadier General Oliver Howard wrote later that a single bullet would take down as many as five or six men, with most of the Yankees unable to fire for fear of hitting their comrades. One regiment, the 15th Massachusetts, was hit by both friend and foe, losing almost 350 men.

Sumner, finally aware of his error, shouted: "My God, we must get out of this!" He did what he could to pull his men back. John Sedgwick was hit three times trying to rally his men and had to be carried off the field. As the Union troops crumbled, Jeb Stuart moved his batteries in close from the northwest and starting blasting them with canister. Rebels also worked their way around to the rear of Sedgwick's division, spreading even more confusion and terror among the Federals.

It was about 9:45. About 2,250 of Sedgwick's men were killed, wounded, or prisoners, while rebel casualties had been slight. The surviving Federals managed to get out of the woods and form a defensive line in the vicinity of the Miller farm. McLaws' enthusiastic Confederates chased after them -- to be torn to pieces by massed II and XII Corps artillery, lined up hub-to-hub and blasting away with canister.

Meanwhile George Greene's men, clinging to their patch of ground in front of the Dunker Church, were out of ammunition. They could only watch the slaughter to their north in the West Woods, and wait for the enemy to turn on them next. They then got a fresh supply of cartridges, just in time to smash two rebel attacks, and advanced a short distance west in pursuit of the second broken assault.

Knowing they were overextended, Greene's men stopped and called for reinforcements, but no more men were forthcoming; McClellan was focused elsewhere. The battlefield to the north of Sharpsburg finally fell relatively quiet. The Confederates had held the line, and an hour later Stonewall Jackson, munching casually on a peach, would tell his chief surgeon: "The Yankees have done their worst." As far as he was concerned, that was true. The Federals would not renew their attacks at the north end of the battleground.

BACK_TO_TOP* It would never be explained why French veered southward instead of following up Sedgwick's division. In any case, French quickly ran into rebel skirmishers and ordered his men forward. Their line of advance took them parallel to the Hagerstown Turnpike, past the smoldering remains of the Munma Farmhouse -- which had been torched by the Confederates to keep it from being used as a strongpoint by Yankee sharpshooters -- towards the northern arc of the Sunken Road.

A regiment of Pennsylvanians ran into unexpected trouble when their advance took them through a farm owned by a Mr. William Roulette, who was hiding out in his farmhouse cellar with his family. Artillery had smashed Roulette's apiary, and the furious bees descended on the Federals in a cloud, breaking up their combat formations as effectively as charges of canister. The officers managed by great efforts to get the men clear and reform ranks.

At about 9:30 AM General Sumner's son and aide, Samuel Sumner, rode up to French to inform him of the disaster in the West Woods, and passed French an order from the general to attack the enemy center in order to relieve the pressure to the north. French moved his three brigades forward up a low, open rise to the south of the Roulette Farmhouse, to attack the Confederates in the Sunken Road at the bottom of the rise on the far side.

There were three of D.H. Hill's brigades in the Sunken Road, about 2,500 men in all, about half the number of French's men. French's lead brigade marched to the top of the ridge, dressed their lines, and then advanced down the open space towards the Confederates at the bottom.

The rebels held their fire. Colonel John B. Gordon of the 6th Alabama found the tense silence "literally oppressive." As the Federals came in range, Gordon's men asked for permission to fire; Gordon replied: "Not yet. Wait for the order." They waited until the Yankees were as close as they dared let them come, a stone's throw distance, and then Gordon shouted at the top of his lungs: "FIRE!" Gordon wrote later: "The effect was appalling. The entire front line, with few exceptions, went down in the consuming blast." The rebels stood up and started blasting into the survivors. The lead Federal brigade stood up bravely, insensibly, to such punishment for five minutes, then the Federals crumbled and fell back to seek cover over the crest of the hill.

French sent in his second brigade, which faltered as well. He then sent in his third brigade as support. The bullets were flying so thickly into them that the fire rippled the grass over which the Union men advanced. Some men broke and ran; others stood their ground and fought. One private, a lieutenant said, sat on top of a boulder, "loading and firing as calmly as though there wasn't a rebel in the country. He said he could see the rebels better there, and refused to leave his vantage-ground."

The Federal attack completely bogged down, with French losing about a third of his division in the futile assault. In the meantime, D.H. Hill's brigades had received reinforcements, in the form of a division of 3,400 men under Major General Richard Anderson. The reinforcements moved up from the south to fill out and extend Hill's line and organize a countercharge that would arc around from the west and flank French's line. Fortunately for French, just at that moment, about 10:30 AM, Sumner's third division, 4,000 men under Major General Israel "Fighting Dick" Richardson, showed up to provide support.

Richardson didn't look much the part of a general. He was a square-jawed fellow who looked more like a farmer, and indeed when he was in camp he would just slouch around with a straw hat on his head and his hands in his pockets, without his uniform coat and its revealing insignia. That had led to some amusing misunderstandings, such as the time when a self-important lieutenant rode up to Richardson's headquarters, curtly ordered Richardson to take his horse, and then, on finally locating the headquarters tent, found himself at attention before the general who had a moment before appeared to be a mere flunky. Richardson, it seems more amused than offended, asked politely: "And what can I do for you, sir?"

The Irish Brigade was Richardson's star, under Brigadier General Thomas Francis Meagher, a dapper and dashing Irishman. Meagher had taken part in an unsuccessful Irish uprising against the English in 1848, had been transported to Tasmania, then escaped to the United States. When the war came, he had raised a brigade of New York Irishmen, leavened with one Massachusetts regiment. The Irish Brigade marched into battle carrying emerald green flags embroidered with a shamrock, a sunburst, and a Celtic harp. They had distinguished themselves in the fighting on the Peninsula. Richardson was proud of them, and they thought much of him.

Now he would ask a great deal of them. Richardson selected them to lead the charge, and so the Irishmen came to the top of the ridge to them descend into the fire. They moved forward just in time to collide with Richard Anderson's men as they made their flanking attack, and the two sides traded volleys in the open. Meagher led them on his white horse. When the color-bearer of one of the regiments was shot, he shouted: "Boys, raise the colors and follow me!"

Seven more men were hit carrying the regimental flag. A captain took up the colors, had them shot in two, took a bullet through his cap, but continued on to the cheers of the men. They drove Anderson's men back to the Sunken Road, but they could not move further. Meagher fell off his horse and was stunned. He claimed he fell the beast had been shot, others said because he was drunk -- after all this time, who can say which? General Meagher was carried to the rear. The assault collapsed, with 540 men killed or wounded.

The Irishmen were relieved by another brigade, led into attack by Richardson himself, leading the way on foot with a sword in his hand, "his face as black as a thundercloud." By this time it was about noon, and though the Federals had suffered terribly, the sheer pressure of their weight had begun to tell on the rebels in the Sunken Road. Richard Anderson was badly wounded, and the coordination of his division fell apart; Colonel Gordon of the 6th Alabama was shot five times, the last one hitting him in the face. He fell over, and would have drowned in the blood pooling inside his cap had not a Yankee put a bullet through that as well.

Federal Colonel Francis Barlow -- in civilian life a lawyer, who had become a real fighter in uniform, having distinguished himself during the Peninsula Campaign -- finally cracked the enemy line when his men managed to get onto a patch of high ground overlooking a bend in the Sunken Road. The road was a straight alley from the vantage point of Barlow's men, and they couldn't have missed the packed-in rebels: if a bullet went past one man, it would hit another, or ricochet off the side of the road into the mass of men. A New York Sergeant wrote later: "We were shooting them like sheep in a pen."

Robert Rodes, in command of that section of the road, gave orders to turn part of his regiment about to face the new threat, but in the confusion the orders were misinterpreted as a directive to pull out. The men fell back through the cornfield of a farm owned by a Mr. Henry Piper, just south of the battle line. The Federals stormed down the middle of the Sunken Road, taking 300 prisoners, and knelt down on a "ghastly flooring" of rebel corpses two and three deep to fire at the fleeing survivors.

While the Federals paused to gather their breath, a pair of Confederate regiments attacked them from the west, hoping to throw back the Federal advance. The rebels were easily driven off, leaving about half their number lying on the field. There seemed to be nothing left to keep the Yankees from cutting Lee's army in half and then destroying it.

Longstreet organized a defense around the Piper House, grabbing hold of every cannon he could find and lining them up to fire canister at the Federals north of him. He went limping around in his carpet slippers, calmly directing fire with an unlit cigar, and taking a nip from a flask every now and then. Long-range Yankee cannon fire from across the Antietam smashed his guns and killed his gunners; he sent his staff officers to replace the fallen men.

* Meanwhile D.H. Hill, never a man to run from a fight, had gathered up some of his men and led a few hundred of them forward in hopes of catching the Federals in the flank. His men ran into the 5th New Hampshire, under the command of a tough Indian fighter named Colonel Edward E. Cross, and were smashed back by a volley from the Union men.

Hill's officers had found a few hundred more troops, and he led them forward on a second charge. In response, Cross stood in front of his men, with a bandanna wrapped around his head, blood trickling down to mix with the dust of black powder on his face, and shouted to them: "Put on the war paint!" The soldiers got the idea, ripping open cartridges and wiping black powder in stripes across their faces. Then Cross shouted: "Give 'em the war whoop!" They let out a horrendous scream and rushed the approaching Confederates, scattering them. Whether the performance caused fear among the enemy or not, one of the New Hampshire men noted: "It reanimated us and let him know we were unterrified."

The rebel attack had been wasteful, but it did give Longstreet time to brace up his artillery defense. He had lined up 20 pieces just to the west of the Hagerstown Turnpike, and they threw out so much metal that the Federal advance slowed to a crawl, then stopped. It was about 12:30 PM, and the battle had gone much like the fight for the Dunker Church. Some of the Yankees had made it as far as the Piper house, but could go no further.

Dick Richardson had taken tremendous casualties, among them Colonel Barlow, who had been badly wounded by a ball of canister. Without artillery support, Richardson's men were vulnerable. He ordered them to fall back behind the low ridge north of the Sunken Road, where they could regroup and reform with French's men for a final assault. Richardson begged for artillery support, but despite the great overall superiority of Federal artillery, he was only able to obtain eight smoothbores that could not match the range of the rifled guns under Longstreet's direction. The Yankee gunners still shot it out as best they could, taking casualties from counterfire.

Suddenly, to the surprise of everyone, a civilian rode up to the Union batteries in a carriage and began to hand out biscuits and ham. The fellow, a Mr. Martin Eakle, picked up some of the battery's wounded and drove them back to safety. He then returned a second time to pick up another load of the injured.

Despite the lack of artillery support, Richardson was ready to renew the attack, but about 1:00 PM a bursting shell cut his side open. Although he would be soon replaced by the aggressive Winfield Scott Hancock, the loss of Richardson removed all immediate pressure to renew the offensive. The Confederates could not have withstood another attack. Longstreet wrote later: "We were already badly whipped, and were only holding our ground by sheer force of desperation." They had taken horrendous casualties, were in a state of extreme disorganization, and were almost out of ammunition.

McClellan had reinforcements available. V Corps, under Major General Fitz-John Porter, was not more than a mile away to the east of the Middle Bridge, and Franklin's VI Corps, having arrived from Pleasant Valley before noon, was holding the Federal gains in front of the West Woods. Franklin was, for once, feeling warlike and wanted to attack into the West Woods, but in an equally unusual reversal of character Sumner, who ranked Franklin, had forbidden it.

Sumner had been demoralized by the bloodying he had taken in the West Woods. When a courier rode up from McClellan suggesting that both Franklin's and Sumner's commands renew the attack if possible, Sumner replied angrily: "Go back, young man, and tell General McClellan I have no command! Tell him my command, Banks' command, and Hooker's command are all cut up and demoralized! Tell him General Franklin has the only organized command on this part of the field!"

When McClellan received this message, he finally stirred himself to go down to the battleground to confer with the two generals. He heard out both men, but after having seen the dead and wounded lying all about, his natural caution asserted itself, and McClellan sided with Sumner. He then rode back across the creek.

It was about 2:00 PM. The Confederates lost about 2,600 men in the battle around the Sunken Road. It was so choked in the end with their dead that they would forever after refer to it as "Bloody Lane". The Federals lost about 3,000. Fighting Dick Richardson was taken to the Pry House, where he would die six weeks later.

BACK_TO_TOP* The bridge to the south of Sharpsburg was an elegant arched stone structure, about 125 feet long and 12 feet wide (38 by 3.7 meters). It was near the farm of a family named Rohrbach, and was known to locals as the Rohrbach Bridge.

That morning, Burnside had all of IX Corps, which was under the command of Brigadier General Jacob Cox, who had taken over after Reno was killed in action at South Mountain. IX Corps consisted of about 11,000 men and possessed 50 guns. At about 9:00 AM, the two generals observed Confederate troops -- Walker's division, in fact -- moving northward from the west side of the Antietam, being sent up the line where they would collide with Sumner's men in short order. This left all of five brigades, maybe 2,000 men in total, comprising most of a division under the command of Major General David R. Jones, to hold the rebel lines in the vicinity of the Rohrbach Bridge.

The far side of the bridge itself was protected by a brigade under the command of "fire-eating" Robert Toombs. He had only 550 men, but they occupied the ridge of a steep bluff about a hundred feet (30 meters) high, littered with boulders from a quarry and marked by a stone wall running parallel to the Antietam. Twelve artillery pieces overlooked the bridge and the area beyond it from the heights above. Other batteries nearby could direct fire from the high ground east of Sharpsburg. It would be very hard and expensive for the Federals to dislodge any force that cared to stand its ground there.

Unfortunately, Burnside, normally genial and enthusiastic, was distressed that day. His old friend McClellan had reprimanded him for being slow on the march over the past week, and Burnside regarded the removal of Hooker from his command as a personal slight; as a result, he was in a passive and indifferent mood. Jacob Cox was normally a fighter and a good leader, but the removal of Hooker's I Corps had left Burnside and Cox in charge of exactly the same command, and the ambiguity in Cox's authority made him uncertain. They were also so fixated on the bridge that they simply forgot to consider other alternatives. They never realized that the Antietam was only about waist-deep along much of their front, and, although they had located a ford about a half-mile downstream the evening before, never thought to perform any serious reconnaissance to find others. They also did not realize just how few Confederates were facing them.

The Yankees and the rebels had been energetically trading shots with artillery over the stream for much of the morning, when a courier rode up about 10:00 AM and gave Burnside orders to attack. McClellan wanted to divert the enemy from the fight at the northern end of the battlefield. He promised to provide support for Burnside once his men had taken the bridge. It was uncertain whether this was to be a diversion or a full-scale assault. This ambiguity confused Burnside still further.

The result was a muddle. A division and a brigade under Brigadier General Isaac Rodman were sent a half-mile downstream to look for the ford that had been located the night before. When they got there, the banks on the far side were too steep, and so they went even farther south to look for a better crossing; it is possible some of their local "guides" were Confederate sympathizers. Back upstream, a brigade under Colonel George Crook simply got lost and found themselves trading shots with the rebels across the Antietam.

Two brigades from Sam Sturgis's division, formed up in tight formations so they wouldn't get lost, were such good targets that they were driven back even before they got to the bridge. Two companies from one regiment, the 11th Connecticut, led by 25-year-old Colonel Henry W. Kingsbury, did manage it to make to the bridge, but that was all. Kingsbury, who was highly regarded by Burnside and others -- and, by another of the many little coincidences in a war of brothers, was Confederate General Simon Bolivar Buckner's brother-in-law -- was shot four times and mortally wounded trying to lead one company across the bridge. The other company tried to wade the stream, but they were shot down before they got halfway across.

It was about noon by the time all this fumbling was complete, and McClellan was becoming agitated with the incompetence and delays. He sent Burnside a barrage of orders, one saying: "If it costs 10,000 men, he must go now." Burnside responded angrily, telling one courier: "McClellan appears to think I am not trying my best to carry this bridge. You are the third or fourth one who has been to me this morning with similar orders."

Sturgis's third brigade, under the command of Colonel Edward Ferrero, was ordered to make the next attack on the bridge. Ferrero's men had little respect for him; his main military virtue was an extremely loud voice that was useful for parade-ground drills, and he owed his rank to political connections instead of ability. However, two of his four regiments, the 51st Pennsylvania and the 51st New York, were particularly good, and had good regimental commanders.

Ferrero lined them up and gave them a speech: "It is General Burnside's special request that the two 51sts take that bridge. Will you do it?" The 51st Pennsylvania had been deprived of their whiskey ration, Ferrero having got the idea that they were excessively fond of it. After a dead silence, a Pennsylvania corporal spoke up: "Will you give us our whiskey, Colonel, if we take it?" Ferrero replied: "Yes, by God! You shall have as much as you want!"

They had more than a promise of whiskey to help them. Two Federal batteries had moved to a position up the Antietam where they could keep the rebels under fire, and Crook's men took a rebel howitzer they had captured, manhandled it into place, and started firing double charges of canister across the stream.

The two attacking regiments formed up in a narrow column, one alongside the other, so that they could charge across the bridge and then diverge in opposite directions once they reached the other side. It didn't work. When they came over the hill at 12:30 PM, the fire was so intense that the neat formation was broken up, and the men dashed to the edge of the stream to find any cover available.

The Union men poured fire over the water at the rebels on the far side. Lieutenant George W. Whitman, brother of poet Walt Whitman, said later: "The way we showered the lead across that creek was nobody's business." 31-year-old Colonel John F. Hartranft, commander of the 51st Pennsylvania, shouted for so long that he grew hoarse: "Come on, boys, for I can't halloo any more!"

Just before 1:00 PM, one of his captains charged across the bridge on his horse, followed by his first sergeant and color bearers. The men of the two regiments jammed onto the bridge and poured across, while the enemy abandoned their positions and withdrew over the hills. The rebels were not panicked, however: Toombs had ordered them to withdraw, since his men were almost out of ammunition and news had come that Rodman had finally crossed the Antietam downstream. The Georgia men fell back to designated positions a half-mile in the rear -- although a Lieutenant Colonel William R. Holmes, caught up in the delirium of the fight, charged at the Yankees with his sword raised, and was promptly all but torn to pieces by bullets. The Georgians had held off the Federals for three hours, inflicting more than 500 casualties while taking only 160 of their own.

Colonel Ferrero would still become a brigadier general for the accomplishments of his men. A few days later, he was given the promotion with all ceremony in front of parade formations of his men. An anonymous voice called out of the ranks: "How about that whiskey?" Ferrero grinned and replied in his booming voice: "You'll get it!" He was as good as his word.

* With the Confederates thrown back, the rest of Sturgis's division filed across the bridge, to link up with Rodman's force moving up from the south, and Crook's brigade which had found a crossing to the north. Unfortunately, Sturgis's men were almost out of ammunition. When Cox was informed of this, he ordered up his reserve division, under Brigadier General Orlando B. Wilcox, to take their place. McClellan's other attacks had bogged down, and he had sent more messages asking for haste. However, Wilcox's men were well to the rear, and the bridge was clogged with traffic. The fighting died down for the moment.

Lee took advantage of the lull to order Jeb Stuart and Stonewall Jackson to scrape up whatever forces they could get their hands on and make a wide movement around the north of the battlefield in hopes of striking the Yankees in the flank. However, the Federals were wise to this possibility, and when the rebel column started out north, they ran into massed artillery lined up on the Poffenberger Farm. Jackson called off the movement, regretfully: "It is a great pity -- we should have driven McClellan into the Potomac."

In the meantime, Lee was scrounging up all the artillery he could spare to bolster his lines to the south of Sharpsburg. There was no more to spare and all he could hope for was the arrival of A.P. Hill and his Light Division, now in a frantic march from Harper's Ferry along the Virginia side of Potomac. Hill rode in ahead of his column at about 2:30 PM. Lee was so glad to see him that he actually hugged Hill. The Light Division was not far behind, but Burnside's men were massing for an attack, and however soon Hill's men arrived could not be soon enough.

McClellan had once more sent an aide to prod Burnside, with orders to relieve him of command if he did not respond, but Burnside was working as hard as he could, and by 3:00 PM had all of IX Corps on the west side of the Antietam, a total of roughly 8,000 men and 22 guns. Wilcox's division, with Crook's brigade in support, was lined up for the attack from north of the bridge. Rodman's division and supporting brigade were lined up to the south. Sturgis's division was in front of the bridge and was to act as a reserve.

The Federals went forward up hilly and relatively open ground, where they found rebel skirmishers taking pot-shots at them from every available hiding place. Wilcox's men pressed forward, clashed with a brigade of South Carolinans, and drove them off back towards Sharpsburg. Rebel gunners realized they were in danger of being overrun, and pulled back as well. Wilcox was now only a few hundred yards from the town, but he was low on ammunition, and ordered his men to halt and wait for the supply wagons to catch up with them.

To the south in rolling hills, Rodman's division was advancing toward the Harper's Ferry Road. In the lead was a Zouave regiment, the 9th New York, advancing forward under the fire of a dozen guns on a low ridge in front of them. They left a litter of casualties behind them but pressed forward under the encouragement of their commander, Lieutenant Colonel Edgar A. Kimball, who shouted: "Bully Ninth! Bully Ninth! Boys, I'm proud of you! Every one of you!" As the Zouaves approached, the Confederate batteries decided it was time to withdraw and limbered up and left. All that was left to stop the Federals were two thinned-out brigades of rebels.

The Zouaves let out a loud HURRAh and charged. The Confederates waited until the Yankees got to within 50 feet (15 meters) of them, and then fired a volley, staggering them. The attackers recovered and started pouring fire back. The Ninth's colors fell. Seven men were shot trying to pick them up again, until Captain Adolph Libaire grabbed and waved the men forward with it: "Up, damn you, and forward!" The Zouaves charged the line, shouting: "ZOU! ZOU! ZOU!" -- and shattered through the rebel line. The Confederates broke, and ran back towards Sharpsburg.

It had been a hell of a fight. One of the Zouaves remembered later: "The mental strain was so great that I saw at that moment the singular effect mentioned, I think, in the life of Goethe on a similar occasion -- the whole landscape for an instant turned slightly red."

The town was now rapidly filling up with Confederate stragglers and wounded. Federal shells struck buildings while civilians hid in their cellars. A few bold Yankee skirmishers were nosing around the outskirts of town; another big push would break the rebels completely. The only intact rebel force in front of Burnside's men was Toombs' brigade, which had been reinforced, but he still only had about 700 men to face thousands of Federals.

If Lee had ever been inclined to panic, he had good reason for it just then, since Hill's division still hadn't showed up. From his headquarters, west of Sharpsburg, Lee kept looking for them. Finally, about 3:30 PM, Lee noticed troops off to the southeast. He asked a lieutenant who was riding with a telescope to identify them, indicating with his bandaged hands that he could not do it himself. The young man told him: "They are flying the United States flag." Lee pointed toward another line of troops not far from the first. "What troops are those?"

"They are flying the Virginia and Confederate flags."

Lee said calmly: "It is A.P. Hill from Harper's Ferry." Hill's Light Division had been reduced to 3,000 men by their hurried march. They had covered 17 miles (27 kilometers) in 8 hours, with Hill prodding them along energetically and leaving those who could not keep up to catch up if they could. Hill's men crossed the Potomac and moved rapidly up to join the fight. Hill split his force, sending two brigades southward to protect his flank and filed his other three brigades just south of Toombs' position.

By chance or design, these three brigades were facing a gap in the advance of Rodman's division. Two of Rodman's regiments, the 16th Connecticut and 4th Rhode Island, were lagging behind and were vulnerable to attack. Rodman observed the Confederates moving in on the flank of his own division and sent an aide to warn the 16th Connecticut. Rodman spurred his horse to ride off and alert other elements in his command -- but a rebel bullet struck him in the chest, mortally wounding him.

In any case, it was too late. At 3:40 PM Hill attacked, his lead brigade smashing into the 16th Connecticut as they crossed into the cornfield of one John Otto. The Connecticut men were entirely green; they had been in service less than a month, and had not only never seen combat, many could barely handle their rifles. They were cut down in scores. The Rhode Islanders moved up to assist them, but in the tall corn they could not tell friend from foe, and many of Hill's men were wearing blue Union jackets they had captured at Harper's Ferry. In the total confusion, the Federals hadn't a chance. The 16th Connecticut broke and ran, and the 14th Rhode Island followed them.

That left the 8th Connecticut, in the lead, completely isolated. Another of Hill's brigades along with some of Toombs' men hit them as well and sent them running. Cox sent up regiments to reinforce his crumbling flank, but they were unable to stem the flow and were forced to withdraw as well. Cox ordered his forward brigades to pull back.

The news of the withdrawal filtered through to Wilcox, and he sent out the order to withdraw. Lieutenant Colonel Kimball of the 9th New York Zouaves, in the lead of the Federal advance, protested vigorously, and only fell back after Wilcox personally ordered him to. As the 9th formed up, Kimball told Wilcox: "Look at my regiment! They go off this field under orders! They are not driven off! Do they look like a beaten regiment?!"

Burnside pulled his men all the way back to the Antietam, where they had launched their attack two hours before. Burnside still had over 8,500 men, greatly outnumbering the rebels, but he was beaten in his own mind, sending urgent requests to McClellan for reinforcements to stop the counteroffensive. McClellan refused, saying he had "no more infantry". In fact, Porter's V Corps and Franklin's VI Corps were still in reserve, having hardly fired a shot all day. The Confederates were on the ropes all up and down the line; one more big push would have finished them off.

The big push never came. The fighting died down to potshots at about 5:30 PM, and the Battle of Antietam was over. Darkness fell about an hour later; the only sounds were the moans and cries of the wounded carpeting the battleground.

The battle had gone on for twelve hours. There were over 22,000 casualties, with 12,000 on the Federal side and 10,000 on the Confederate side. Generals had fallen in numbers on both sides. The dead carpeted the Cornfield; Hooker would later say that in all the war he had never seen "a more bloody, dismal battlefield." Corpses choked the Sunken Road. Aid stations, one providing the ministrations of Clara Barton, who had been close enough to the shooting to have a bullet pass through her skirt, did what they could to help the wounded.

Lee's army had performed an incredible feat just by surviving in the face of overwhelming odds. They had hurt the Federals worse than they themselves had been hurt, but the Confederate drive into the North was over for 1862. In addition, the casualties among the Yankees had not been so much greater than those of the rebels, who could not afford such losses.

BACK_TO_TOP