* The initial Japanese attempt to drive the US Marines off Guadalcanal was poorly thought out, thanks to overconfidence, and ended in a complete Japanese defeat. The two sides settled into a gradually escalating war of attrition.

* For the moment, the IJN felt satisfied with their victory at Savo Island, but there remained the small matter of the American landing force. The victory disease also infected IJN intelligence, resulting in an estimate of only 2,000 US Marines on Guadalcanal. The IJN asked the IJA to mop them up, and appropriate orders were relayed to General Hyakutake, commander of the IJA 17th Army in Rabaul. Hyakutake hadn't given the matter much thought up to that time, and the delay in getting the IJA involved gave the Marines on Guadalcanal vital breathing space.

6,000 Japanese troops were available for operations against Guadalcanal, including a 500-man IJN Special Naval Landing Force; an IJA detachment of 2,000 men under Colonel Ichiki Kiyono; and 3,500 IJA soldiers under General Kawaguchi Kiyotake. The IJA had no idea that there were 11,000 Marines on Guadalcanal, and 6,000 on Tulagi -- though American numbers were offset by the fact that they had been left with barely enough food for a month, and inadequate ammunition and other supplies. Most of the heavy weapons and equipment hadn't been unloaded from the transports before they left.

The supplies that had been landed were widely dispersed in small dumps to make them less vulnerable to destruction by enemy action. The Japanese performed bombing raids almost every day at noon -- the Marines called it "Tojo Time" -- and IJN destroyers and cruisers often steamed off the coastline and fired their main guns inland. Even without the bombardments, conditions were difficult. Guadalcanal looked like a tropical paradise from a distance, but up close it was a hot, stinking jungle that smelled like a cesspool. It was populated by spiders, centipedes, leeches, clouds of malarial mosquitoes, and other vermin of which the Marines had never seen the like. The flies were so thick it was difficult to eat without swallowing them with each spoonful.

The Japanese who had run away during the landing were now becoming a more tangible threat as well. On 12 August, a patrol of 26 Marines took a boat up the shoreline to follow up a hint by a Japanese prisoner that there were some other Japanese who might want to surrender. They found Japanese -- but not ones who were in any mood to surrender. Only three of the patrol survived, managing to swim away to safety.

The hardships motivated rather than demoralized the Marines. To survive, they would have to dig in and get the airfield finished. They named it "Henderson Field", after Major Lofton R. Henderson, a Marine pilot who had been lost at Midway. The Marines only had a single bulldozer, and only its operator, Private Roy F. Cate, was allowed to touch it. It worked until it fell to pieces. The Marines also used the tools and supplies left by the Japanese to get the job done.

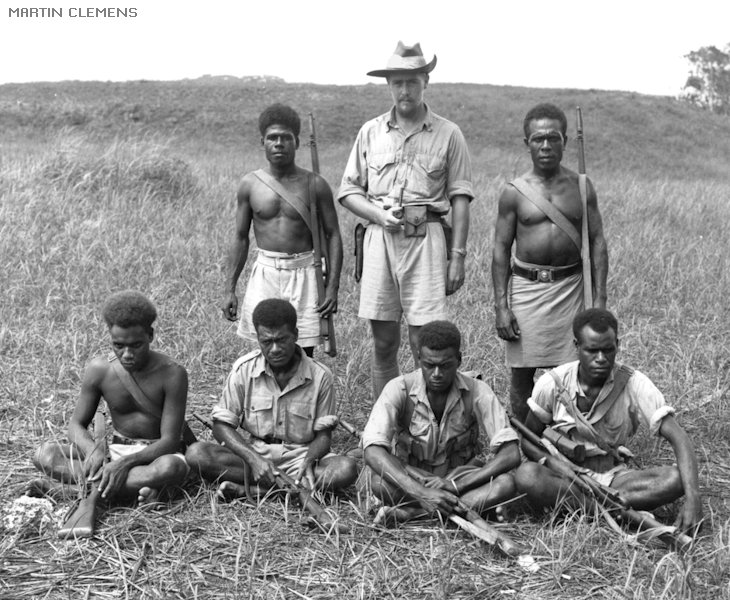

The Marines found they had help from the locals, under the supervision of the resident coastwatcher, a Briton named Martin Clemens, who walked into Marine lines on 15 August with an escort of natives. The locals had no servile fondness for outsiders, but nobody had ever considered the Solomons particularly worth exploiting -- indeed, they were for good reason seen more as pestilential -- and so the natives had been mostly left alone, with such annoyances as caused by outsiders balanced by the usefulness of their trade goods and the like. The Japanese were more assertive and had little interest in winning friends; as a rule, they did not do so. The locals also generally did not perceive the Japanese as being on the winning side over the long run.

Supplies were also starting to come in by sea again, if in a limited way. With American sea transport at risk from Japanese naval and air power, for the time being supplies were being sent in by APD fast destroyer transports out of Espiritu Santo. The APDs were effectively "blockade runners" -- able to get in and out of the battle area quickly, with their schedules arranged so they would arrive near sundown, be unloaded in the dark, and depart before sunrise. Unloading them didn't take too much time because they couldn't carry very big loads; they were also able to fight back to a degree, if it came to that.

Three APDs showed up on the same day, 15 August, with supplies for the air base. On 20 August 1942, the destroyer transports were back with another supply load. By that date, Henderson Field was ready for use. That evening, as General Vandegrift wrote later: "From the east, flying into the evening Sun came one of the most beautiful sights of my life -- a flight of 12 SBD dive bombers."

The "Dauntless" dive bombers were under the command of Marine Lieutenant Colonel Richard D. Mangrum. Vandegrift wrote, with a bit of heartfelt sentimentality not normally associated with a US Marine general: "I was close to tears and I was not alone, when the first SBD taxied up and this handsome and dashing aviator jumped to the ground. 'Thank God you have come,' I told him."

The isolation of the Marines was ending. The dive bombers were soon followed by 19 Wildcat fighters, led by Marine Captain John L. Smith. The aircraft had flown from the LONG ISLAND -- hastily rebuilt from a cargo ship, the MORMACMAIL, to become the US Navy's first baby or "jeep" carrier -- standing off about 320 kilometers (200 miles) south of Guadalcanal. Since the code name for the island was CACTUS, the aircraft became the core of the "Cactus Air Force", with more Marine, Navy, and US Army Air Forces (USAAF) aircraft soon arriving to add their weight.

The initial USAAF contribution was the Bell Airacobra, an unconventional aircraft with the engine in midbody, spinning the prop through a driveshaft, and car-style doors for the pilot. Lacking a turbocharger system, it was no good for fighting at altitude; the Airacobras were scrambled during Japanese raids just to keep them from being bombed. They were, however, heavily armed -- with six machine guns, plus an automatic cannon firing through the propeller spinner, and were capable of carrying a light bombload. They proved very useful at battlefield support, giving IJN troops good cause to hate them. An Airacobra could take on Japanese aircraft at low level, but it lacked the agility of the Zero and was not really a match for it.

The Cactus Air Force had pilots from three different armed services, but they were all under the command of Marine Major General Roy Geiger. Henderson Field was a very rough installation at the time, lacking the facilities to handle heavy bombers or other large aircraft. However, from the start of operations on the airstrip, supplies were flown in Espiritu Santo using Douglas R4D transports, the Navy designation for the stalwart Douglas DC-3 / C-47. The R4Ds couldn't compete with sealift transport in terms of cargo volume, but they could carry vital items such as aviation gasoline, the typical load being about 1,360 kilograms (3,000 pounds), and also fly up to 16 wounded Cactus personnel out for hospitalization. An air shuttle was set up that operated on a daily basis, weather and the combat situation permitting. With air power available on Guadalcanal, it was also seen as more practical to bring in transport vessels in daytime -- though they were still far from perfectly safe.

BACK_TO_TOP* Assistance had come just in time, since the IJA was preparing to retake Guadalcanal. Just before midnight on 18 August, six Japanese destroyers had dropped off Colonel Ichiki Kiyono and 915 of his men at Taivu Point, 32 kilometers (20 miles) east of Henderson Field; the destroyers briefly pounded American positions as they departed. Ichiki had been ordered to wait for the rest of his men, who would arrive the next week, but he was confident of victory and set off for Henderson Field immediately, leaving behind a detachment of 125 men to guard the beach.

Marine lookouts heard the ships go by. General Vandegrift also received reports of a landing to the west, which in fact was the 500-man Special Naval Landing Force. While this smaller unit would never take significant actions against him, Vandegrift was concerned that the Japanese were organizing a counterattack, and sent out patrols to locate the enemy.

Ichiki's men had combat experience in China, and he felt they could easily defeat the soft Americans. Ichiki made little attempt to determine enemy strength, and failed to realize there were about five times more Americans than he thought there were. Colonel Ichiki was so confident that he wrote in his diary ahead of time: "21 August. Enjoyment of the fruits of victory."

In fact, the Marines were waiting for him, since a Marine patrol had run into a Japanese work party on Wednesday, the 19th, during a sweep by three companies of Marines. The Marines patrol all but wiped out the Japanese; the Marines noted they were IJA troops, not IJN naval forces, suggesting that Japanese reinforcements had arrived. Inspections of the dead showed them carrying maps and diaries that also suggested an attack was imminent.

Martin Clemens' local scouts also proved useful, and in some cases courageous. A local named Jacob Vouza led a group of his fellows on a search and managed to locate Ichiki's force, but when Vouza tried to crawl close to learn more, he was captured by the Japanese. Vouza was tied to a tree for interrogation, beaten to a pulp with rifle butts, stabbed twice with bayonets in the chest, and when he still refused to talk, stabbed in the throat and left for dead. Incredibly, he survived and managed to chew through his ropes that night. He crawled back to Martin Clemens and warned that hundreds of Japanese were preparing to attack them. "I did not tell them," he said before he passed out. Vouza would recover, and would be awarded the Silver Star and even be granted the rank of sergeant-major by the Marines. However, by the time he had informed Clemens of the impending attack, it was already in progress.

* In the dark hours of the morning of Friday, 21 August, two weeks after the landings on Guadalcanal, Ichiki led his men in an assault on Marine positions on the western side of the Ilu River, mismarked on Marine maps as the Tenaru River, a stream that ran north across the western approaches to Henderson Field. The main attack was across a sandspit at the mouth of the Ilu and jumped off from a coconut grove on the east side of the river.

The Marines were dug in, waiting, and simply slaughtered Ichiki's men. They were hit by Marine 37 millimeter anti-tank guns firing canister rounds; tripped and tangled by barbed wire; mowed down by Marine machine guns and Springfield rifles. The Japanese managed to break through the Marine lines in a few places, leading to vicious hand-to-hand fighting, but Marine reserve platoons counterattacked and drove them back. The Japanese persisted in their futile assault until sunrise.

Vandegrift, seeing that his defenses were solid, ordered a counterstroke, sending a reserve battalion upriver to cross over and hit the Japanese from the flank and rear. The Japanese had fought with reckless courage during the night, but had suffered terribly. They had not expected such savage resistance, and when the counterattack hit them, they broke and ran. American aircraft strafed and bombed them as they fled up the beach.

Early in the afternoon, Vandegrift's encirclement trapped most of them in the coconut grove. Their position was hopeless, but they would not surrender. Vandegrift decided he had to simply exterminate them, sending five M3 Stuart light tanks across the sandspit into the coconut grove. The tanks pushed through the grove, mowing down the Japanese with canister and machine guns, or simply running them down until, as Vandegrift wrote, "the rear of the tanks looked like meat grinders." The Japanese managed to blow a track off one of the tanks -- but the other machines simply closed ranks with the disabled vehicle, rescued the crew, and resumed their slaughter.

The story was told that Ichiki committed seppuku -- ritual suicide by disembowelment -- but that may have been an invention after the fact, propaganda intended to glorify the colonel's memory. Ichiki would have only taken such a measure after all was completely lost, and the Marines were so merciless and thorough in their killing that it seems more likely he was cut down with his men. Only two men of his assault force survived, by hiding in the water until the sun went down, allowing them to escape to rejoin their colleagues at Taivu Point.

Almost 800 Japanese were dead, at the cost of 35 dead and 75 wounded Americans. It was the first pitched battle of the war between the US Marines and the IJA, resulting in a resounding Marine victory. However hard the IJA pressed the Marines for the rest of the war -- and sometimes it would be very hard -- the Marines never had any more than temporary doubts that they could beat the IJA.

* As far as the Japanese went, they would prove slow to learn that courage, without competent leadership, was a recipe for disastrous failure. The IJA was used to fighting weak enemies who could be expected to crack when attacked with sufficient enthusiasm; when the enemy knew how to fight and didn't feel like giving ground, enthusiasm simply got more Japanese killed, without inflicting a proportional amount of harm in return.

To a degree, the slaughter of Ichiki's force was a wake-up call to the IJA and IJN commands. They were beginning to realize that the battle for Guadalcanal was not going to be a sideshow; that they were up against a formidable enemy; that the IJA and IJN would have to work more closely together to defeat the Americans. Fortunately for the Americans, it didn't wake the Japanese up enough. They would keep raising the stakes by what they judged enough to do the job, only to find the Americans managing, if sometimes by the hardest, to stay a step ahead of them.

The Battle of the Ilu River was a louder wake-up call to Vandegrift and his Marines. Vandegrift wrote to a colleague a few days later:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

General, I have never heard or read of this kind of fighting. These people refuse to surrender. The wounded wait until men come up to examine them ... and blow themselves and the other fellow to pieces with a hand grenade.

END_QUOTE

The Japanese showed little mercy, and expected little in return. To the extent the Marines thought of taking prisoners, they soon decided not to bother. When moving among Japanese bodies littering the battlefield, Marines acquired the habit of putting a bullet into any of them that didn't seem sufficiently dead. The Americans had their own streak of complacency, but they were gradually becoming wiser.

It continued to be a painful learning curve. In the dark hours of the morning of 23 August, the USS BLUE was part of a pack of three destroyers hunting for Japanese vessels trying to land troops. They succeeded only too well, the IJN destroyer KAWAKAZE putting a torpedo into the BLUE, blowing its stern off. Although an attempt was made to tow the BLUE into Tulagi harbor, it had to be scuttled that evening; things were clearly about to happen in the seas around Guadalcanal, and no more time could be spent trying to rescue the crippled destroyer.

BACK_TO_TOP* The IJN was hooked, had long been hooked, on the notion of the "decisive naval battle", the idea that a naval war could and should be resolved in a single decisive engagement. There were historical reasons for this, but it was also reinforced by necessity, since the IJN knew it couldn't win a war of attrition with the US Navy, seen for decades by the IJN as their likely adversary in a conflict. The "decisive battle" concept did make a certain amount of sense -- but it also represented a degree of wishful thinking, like trying to run a business on the expectation of hitting the jackpot, and then assuming that would settle everything for good. Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku wanted to make Guadalcanal the bait for the "decisive battle" with the Americans that the Japanese hoped would finally resolve the war in the Pacific.

The remainder of Ichiki's troops had been en route to Guadalcanal in transports when the news of the defeat at the Ilu River arrived. The transports regrouped and joined up with an escort force consisting of a cruiser and several destroyers, with the convoy under the general command of Rear Admiral Tanaka Raizou -- an aggressive officer who the Americans would come to know only too well. Tanaka's group amounted to an independent component of a larger naval attack force under Vice Admiral Kondou Nobutake steaming eastward of the troop convoy to find the American fleet. The attack force included the two heavy carriers ZUIKAKU and SHOUKAKU, the light carrier RYUUJOU, two battleships, 11 cruisers, and 19 destroyers.

Admiral Ghormley was ready to do battle and dispatched Fletcher with Task Force 61 to meet the Japanese. Task Force 61 consisted of the carriers SARATOGA, ENTERRPRISE, and WASP, along with seven cruisers and 18 destroyers. By sunrise on Sunday, 23 August, Task Force 61 was in position some 240 kilometers (150 miles) to the east of Guadalcanal. Later that day, American patrol aircraft spotted Tanaka's little fleet of transports and their escorts -- but Tanaka abruptly changed course that afternoon to successfully throw the Americans off the scent, and Kondou soon did the same with similar results.

Fletcher believed that the abrupt disappearance of the Japanese meant an engagement wasn't imminent, and so he sent the WASP and its escorts south to refuel. In fact, the Japanese were simply maneuvering to lure the Americans into a trap. The light carrier RYUUJOU and its escorts were sent out separately as a diversion. At about 0900 hours on Monday, 24 August, an American patrol plane spotted the diversionary group, about 450 kilometers (280 miles) to the northwest of Task Force 61. Fletcher hesitated until RYUUJOU launched air strikes against Henderson Field early that afternoon.

Fletcher immediately launched 30 Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers and eight Devastator torpedo bombers against RYUUJOU. In mid-afternoon, the American found the little carrier and hit it with about four bombs and a torpedo. The carrier went dead in the water and soon sank. However, the attack alerted the main Japanese force to the location of Task Force 61, and Japanese carriers launched air strikes of their own. Aichi D3A1 dive bombers managed to penetrate the Wildcat fighter screen and scored three hits on the ENTERPRISE. Although the ship's damage control teams responded quickly and effectively, 76 sailors were killed and the ENTERPRISE had to return to Pearl Harbor for major repairs that would require months to complete.

Fletcher now had only the SARATOGA available for battle. Not only did that reduce the number of aircraft available for a fight, but if the SARATOGA were hit, his fleet would be left without air cover. He decided to withdraw.

* Although the main Japanese fleet retired as well once Task Force 61 left the battle, Tanaka's troop transport convoy continued on into the darkness on 24 August. Tanaka was aware that he was vulnerable to air attack, but he sent his destroyers ahead to pound Henderson Field and hopefully suppress Marine air strikes.

Fortune does not always favor the bold. In mid-morning on Tuesday, 25 August, the convoy was discovered by a roving patrol of eight Marine Dauntless dive bombers. The bombers sank the transport KINRYU MARU and badly damaged Tanaka's flagship, the light cruiser JINTSUU, with Tanaka knocked unconscious; when he recovered, he switched his flag to the destroyer KAGERU, the JINTSUU steaming to Truk for repairs.

While Tanaka's destroyers were engaged in rescue operations, they were attacked by USAAF B-17 Flying Fortress bombers out of Espiritu Santo. Prewar USAAF doctrine had envisioned precision high-altitude bombing against naval targets, but combat experience had by that time generally proven it ridiculously ineffective; however, one of the B-17s scored a wildly lucky hit on the destroyer MUTSUKI and sank it -- much to the surprise of both the captain of the MUTSUKI and the B-17's aircrew.

Even with this upset, Tanaka never gave up easily and was determined to continue. He would have done so if he had not received orders radioed to him from Rabaul. He was ordered to return to Shortland Island, a small island off Bougainville that was being used as an advance staging area for operations against Guadalcanal. Ichiki's reinforcements never arrived; the Japanese attempt to destroy American naval forces around Guadalcanal and reinforce the island was a bust.

* The second naval battle of Guadalcanal, the "Battle of the Eastern Solomons", was effectively a draw, both sides taking a few painful blows but suffering no critical harm, the military situation remaining much the same after the clash as it had been before. The US Navy could take credit in taking a bite out of Japanese air power -- the Japanese losing about 75 aircraft, while the Americans lost about 25. The Americans could easily make good their air losses while the Japanese could not, with replacement of skilled aircrew a particular difficulty. The Americans also learned valuable lessons about naval air power, in particular the need to improve coordination of and communications for fighter defense of fleet task forces.

The first coordinated Japanese attempt to drive the Americans off of Guadalcanal had certainly failed, but that was far more due to Kondou's timidity than to anything the US Navy had done. It hadn't been much of a contest, neither side having demonstrated an excess of aggressiveness: Kondou had clear superiority of naval forces and had been certainly capable of doing the Americans a lot more harm after the exchange of blows on 24 August -- but having lost control of the battlespace, he simply withdrew.

Kondou left with the illusion that he had done the US Navy far more damage than he actually had. While it is common in the confusion and exuberance of battle to exaggerate damage inflicted on an enemy, the pilots reported sinking or badly damaging a dozen warships, including three carriers and a battleship. The US Navy was also prone to exaggerate damage inflicted on an enemy, but the IJN would, over the long run, go wild with claims of illusory victories.

BACK_TO_TOP* By that time, supplies and reinforcements were flowing in quantity to the Marines on Guadalcanal. On 1 September, a detachment of the 6th Seabees arrived to take over the task of building up Guadalcanal into an operational base. Many of the Seabees were older men -- the average age being in the early thirties -- with experience in the construction industry who had decided to put their expertise into use on the front lines. Many of the Marines were hardly out of high school and joked: "Never hit a Seabee, he might be your dad." In some cases, a Seabee could have been their granddad; while the cut-off age for Seabee enlistments was set at 50, there were tales of a few men over 60 managing to lie their way in.

The Seabees had their work cut out for them, in particular being challenged by heavy tropical rains and the mud that came along with them. They quickly turned Henderson Field into an all-weather airstrip by laying down a bed of gravel, coral, and clay, raised to permit proper drainage, then covering it with perforated steel planking known as "Marston mat". The Seabees also set up proper base facilities, including shelters and defensive installations, while quickly repairing damage from Japanese naval bombardments and air raids.

The island, however, took its toll on all the Americans there. The heat and vermin were mere nuisances compared to dysentery, malaria, and fungal infections. Many of the Marines were still reluctant to take atabrine -- an anti-malarial medicine developed by the Germans in the early 1930s, being used as a replacement for quinine since the primary source of that drug was the Dutch East Indies and its cinchona tree plantations, then in Japanese hands. The Marines distrusted atabrine since they believed it would make them impotent. The fact that prolonged usage made their skin turn a striking shade of yellow, the drug having been developed out of research on dyes, didn't reassure them, nor did the facts that it could cause nausea and even fits of psychosis. Medics were ordered to stand in chow lines and watch each man swallow an atabrine pill before allowing them to eat.

* The Japanese did not intend to make life any easier for them. They sent in bomb raids and fighter sweeps, and Marine units skirmished with Japanese infantry. The Americans, having air superiority, owned the seas around Guadalcanal during the day, but the aircraft had little capability of fighting in the dark at the time, and after sundown the IJN took over. Nighttime destroyer runs ferried Japanese reinforcements and supplies to the island, operating on such a regular basis that the Marines started calling the runs the "Tokyo Express".

There wasn't much the Americans could do about it at the moment, but at least the necessity for the IJN vessels to be well gone by sunup hobbled their ability to offload supplies. Both sides were frustrated by their failure to obtain around-the-clock control of the battlespace, with both sides seeking means of doing so.

General Kawaguchi had arrived at Shortland with 3,500 men and wanted Rear Admiral Tanaka to get them to Guadalcanal immediately. Tanaka was in agreement with Kawaguchi's goal, but the two men disagreed on the means of accomplishing it. Kawaguchi wanted to transport his men in barges to ensure that they could bring along adequate food, equipment, and supplies, since the lack of such essentials had been a major factor in Ichiki's disastrous defeat. Tanaka had received a nasty taste of what it was like to try to run ships to Guadalcanal in the face of Allied air attacks, and insisted on using destroyers to make fast runs under cover of darkness.

Kawaguchi finally suggested a compromise. He and 2,400 men would be carried by destroyers to Taivu Point, while 1,100 of his men would be sent by barges to Kokumbona, a village about 16 kilometers (10 miles) west of Henderson Field. This detachment would be under the command of one of Kawaguchi's regimental commanders, Colonel Oka Akinosuke.

Oka believed the barges would work. He didn't like the odds of making the run to Guadalcanal in Tanaka's destroyers, and felt that the motorboats could survive by skipping from island to island in the dark and hiding out during the day. Tanaka agreed to the plan and it was set in motion. General Kawaguchi was a thoughtful man, possibly too thoughtful for the liking of his superiors, and he had misgivings about the operation.

Kawaguchi's misgivings were no doubt amplified when Tanaka tried to run troops in on destroyers on 28 August. They were pounced on by Marine Dauntlesses, which damaged several ships and blew the destroyer ASAGIRI up with a direct hit; it was a good day for the Americans, the US Navy also sending the IJN submarine I-123 to the bottom. Tanaka's landing effort was called off, but he conducted further runs over the following days, enjoying revenge for the loss of the ASAGIRI by the sinking of the APD USS COLHOUN by Japanese aircraft on 30 August.

Tanaka completed his ferry mission without further interference. On the evening of 31 August, eight of his destroyers dropped Kawaguchi and his men off at Taivu Point to the east of Henderson Field. There they met with the survivors of Ichiki's force, who were ragged and starving. They told the newcomers that they had been under continuous attack by American aircraft.

Kawaguchi moved westward to an abandoned village that night, and the next day they found out that Ichiki's men weren't exaggerating the air attacks. Marine Wildcats and Dauntlesses, as well as Army Airacobras, searched for Kawaguchi's men. The Japanese remained hidden for the day, but at night on 1 September the second group of 1,000 of Ichiki's men reached Guadalcanal was finally dropped off. There was a communications mixup, and Kawaguchi's men fired on them, killing two and wounding eight. That was unfortunate, but much worse, the firing alerted the Americans to Kawaguchi's position, and aircraft began to pound the Japanese mercilessly.

* Despite the air attacks, Kawaguchi remained where he was, waiting for word that the Oka's detachment of 1,100 men being transported by barge had arrived west of Henderson Field. Kawaguchi didn't receive word from Oka that he was preparing to land until 4 September, and communications didn't greatly improve from that time on. Kawaguchi waited two days, and then set out with 3,100 men on Sunday, 6 September, leaving a rearguard behind. He planned to loop through the jungle and attack the airfield from the south, while Oka launched a diversionary attack from the west.

The Marines were not sitting idly, waiting to be attacked. On Tuesday, 8 September, the 1st Marine Raider Battalion under Lieutenant Colonel Merritt A. Edson, known as "Red Mike" for his red hair, hit the beach near Taivu Point to attack the Japanese. The Americans had actually seriously underestimated the number of Japanese present, having not believed reports of native scouts that there were thousands there, and might have got into real trouble -- but Kawaguchi, observing the passage of American vessels actually unrelated to the raid and concluding that a major amphibious landing was being conducted, similarly overestimated the number of Marines and hastily pulled his force back inland.

The Marines descended on a village that Kawaguchi had been using for his headquarters, with Cactus Air Force aircraft supporting their assault. A Japanese rearguard fought back for a short time and then faded into the jungle. The Marines captured intelligence information -- most significantly confirming the native scout reports of a Japanese buildup -- as well as Kawaguchi's dress uniform. One Marine commented: "The bastard must have been planning to shine in Sydney society."

They wrecked everything they could -- even pissing on the food supplies left behind by the Japanese -- packed up on tins of crab and beef, and departed. Only two Marines were killed, compared to over two dozen Japanese. One of the Japanese survivors wrote with a certain grudging admiration: "It is maddening to be the recipients of these daring and insulting attacks."

However, the Marines had been lucky that Kawaguchi hadn't stood and fought, and the Americans were certainly not having things entirely their own way at the time. The Tokyo Express was a significant nuisance, shelling Henderson Field almost every night. The Solomons are arranged in roughly two rows of islands, and the destroyers had to run down between the rows. The Americans called this channel "The Slot", and it had become an avenue for running clashes.

Following a report of Japanese on Savo Island, on 4 September the destroyer-transports LITTLE and GREGORY dropped off Marines there, who investigated and found nothing. The two APDs took the Marines back to Guadalcanal; having dropped off their passengers, in the dark hours of the morning of Saturday, 5 September, they went back out to sea. They observed firing from offshore into American positions, and assumed it was a Japanese sub making a nuisance of itself.

They went into attack it, only to realize from radar that it was the Tokyo Express instead; they still pushed on to perform a hit & run attack in hopes of distracting the Japanese -- but as they did so, a Catalina flying boat, observing the bombardment as well, dropped parachute flares to illuminate the battle area. The IJN immediately spotted the two APDs; the lightly-armed vessels were hammered to pieces and sank immediately. Admiral Turner commended the courage of their crews, but the US Navy had still lost two valuable warships.

* Kawaguchi assumed that Oka's force was intact, but that was not the case. The trip in the barges had been a disaster, with Oka's force of 1,100 being dispersed by storms and air attacks. The barges were generally uninhabited when they were shot up and most of the troops managed to get to Guadalcanal, but it took a week to assemble them, and due to the loss of food and ammunition they were not very combat-effective.

The trek through the jungle was a nightmare. The Japanese were poorly fed and were increasingly suffering from malaria and other diseases. They struggled through the dark and tangled forest, carrying heavy and exhausting burdens of weapons and ammunition.

Although the Japanese offensive was not starting out well, General Vandegrift was still uncertain that he could hold Henderson Field. His Marines were stretched thin, attrition had whittled down the Cactus Air Force, and Admiral Ghormley was waffling on naval support. The Lunga River curved south and west of Henderson Field, and to the south was overlooked by a long, low ridge. Vandegrift decided correctly that the Japanese would attack him along this ridge, and sent Edson and his Raider battalion over to the far slope of the ridge to hold it.

Kawaguchi, however, believed or at least hoped he had the element of surprise. He also underestimated the number of Americans around Henderson Field by a factor of two to three, and never fully appreciated just how hard it was to move and control men over terrain that would have been difficult enough even if it hadn't been overgrown by noxious jungle. Coordinating attacks would prove difficult, with the terrain greatly favoring the defense.

The Japanese assault jumped off after dark on Saturday, 12 September, with the fighting continuing into the morning of Monday, 14 September. The Marines thought the Japanese were shouting "GAS ATTACK!" when they charged as an intimidation tactic, a tale that still lingers, but they were actually shouting: "TOTSUGEKI (CHARGE)!" The Japanese repeatedly pressed their attacks very hard, only to be driven back each time by artillery and the determined resistance of the Marines. When some of Edson's men wavered and started to fall back on their own, Edson told them in his raspy, quiet voice: "Go back where you came from. The only thing they've got that you haven't is guts."

The Japanese might have cracked the American line and rolled up the defense, but the attacks were performed piecemeal, resulting in a hideous slaughter of Japanese troops, the worst casualties being inflicted by the heavy and accurate American artillery fire. There were some breakthroughs, but they were quickly mopped up -- three Japanese soldiers charged General Vandegrift in front of his command post, the three being gunned down immediately. Lingering fighting continued on the flanks of the Marine position into the next day, but all the Japanese accomplished was to increase their number of casualties.

After pulling out, Japanese survivors suffered through a misery march, characterized by more disease and starvation, looping west to where Oka had landed. The ridge where they had come to ruin became known as "Bloody Ridge" or -- there being lots of bloody ridges in the history of warfare -- "Edson's Ridge". The Japanese had lost roughly 800 men, while the Marines lost about 100 men killed and 220 wounded. The reckless courage of the Japanese soldiers could not compensate for the poor execution of the attack. The fight was a tough one for the Marines, but the end result was almost a replay of the one-sided Battle of the Ilu, on a somewhat larger scale.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Marines had scored a significant victory over the Japanese at Edson's Ridge, but the battle was not decisive. Naval support for the Marines was still precarious. The damaged carrier ENTERPRISE was out of the battle; on 31 August, the IJN Japanese submarine I-26 had put two torpedoes into SARATOGA, also damaging it badly enough to take it out of action for some time. There were a number of relatively minor injuries from the attack, with Admiral Fletcher gashing his forehead. The I-26 had been depth-charged by American destroyers but escaped, with the submarine's captain reporting that US Navy anti-submarine tactics were weak.

SARATOGA's aircraft flew to Espiritu Santo, to then fly to Guadalcanal and join the Cactus Air Force for the time being. SARATOGA limped back to the USA for repair, being temporarily patched up in Tongatabu with a concrete plug installed by Seabees. Fletcher accompanied the carrier home; while the SARATOGA would be back in action in about three months, Fletcher would never return to frontline combat. Admiral King, a man with notoriously little sufferance of fools, had long had doubts of Fletcher's notions of how to fight naval battles, but Nimitz had stood up for him. King finally decided Fletcher needed to be given assignments more in line with his abilities.

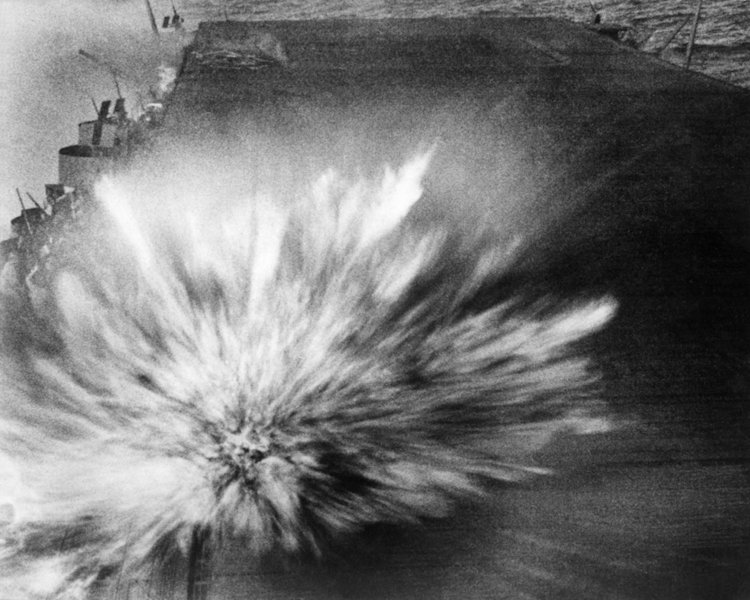

With ENTERPRISE and SARATOGA out of the fight, that left WASP and HORNET to support the battle for Guadalcanal. The two carriers were assigned to a task force protecting a convoy of transports to Guadalcanal; on Tuesday, 15 September, the IJN submarine I-19 penetrated the destroyer screens and launched six torpedoes, three hitting the WASP, one each hitting the battleship NORTH CAROLINA and the destroyer O'BRIEN.

The WASP went down that afternoon, being finished off by torpedoes from the destroyer LANDSDOWNE; most of the crew was saved, though hundreds were lost. The NORTH CAROLINA survived -- indeed, although the battleship had been hit hard, the vessel didn't even slow down, a tribute to the solidity of her construction and the skillful damage control of her crew -- and returned to Pearl Harbor, spending a month in repair. The O'BRIEN tried to limp back stateside with patchwork repairs, but had been too severely damaged and broke up at sea two months later, all crew surviving. Incidentally, some sources claim the torpedoes that hit the NORTH CAROLINA and O'BRIEN were actually from a second IJN submarine, the I-15, but the general consensus now is that the I-19 fired all the torpedoes.

With the loss of the WASP, the US Navy was down to one operational aircraft carrier in the entire Pacific, while the IJN still had two large carriers and a number of light carriers. Fortunately for the Americans, the Japanese never really understood and pressed their advantage, the blunder being all the greater because even they knew that in the next year, American warship construction would tip the scale back in favor of the USA, and the IJN would never be able to catch up.

* There was also a silver lining for the Americans in the very dark cloud of the sinking of the WASP; the severe learning experience provided by Guadalcanal to the US Navy extended to anti-submarine warfare procedures, and improvements in anti-submarine tactics would ensure attempts by Japanese submarine captains to sneak up on well-protected American task forces would become increasingly hazardous. The I-19 would be sunk with all hands by a US Navy destroyer a little over a year later.

In addition, the convoy got through to Guadalacanal, arriving at sunrise on 18 September with over 4,000 Marines, the remainder of the 1st Marine Division, as well as aviation gas and other supplies. Destroyers in the escort force shelled Japanese positions for good measure, with the unloaded convoy departing that evening. More aircraft came in to reinforce the Cactus Air Force, with a bout of poor weather curtailing Japanese air attacks for a week or so and giving the American pilots some breathing space.

Guadalcanal's isolation had now effectively ended, with Vandegrift receiving regular supplies and reinforcements, the troops going back to full rations. He was feeling confident, and became angry when a reporter told him that there were grave doubts about the operation in Washington and in Ghormley's headquarters in Noumea. The reporter asked: "Are you going to stay here?"

"HELL yes! Why not?!"

BACK_TO_TOP