* Following the declaration of war, the Americans attempted to launch dual invasions of Canada -- both of which came to ruin, more due to lack of military preparation than the strength of the defending forces. Ironically, although the US Navy hadn't been expected to accomplish much against Britain's overwhelmingly more powerful Royal Navy, thanks to the boldness of its leadership, the US Navy struck a series of blows against the British. The battles at sea were strategically inconsequential, but they did much to gloss over American failures on land and encourage continuation of the war.

* From one perspective, President Madison's confidence in winning the war seemed misplaced, since America's armed forces were ill-prepared, tiny, and scattered. A series of border forts garrisoned by very small US Army detachments stretched along the Canadian boundary:

These forts were isolated in very wild territory, featuring few or no roads capable of supporting supply by wagon, with such supplies as could be hauled over land generally carried over trails by pack horses or mules -- and even such beasts of burden generally had to carry all their own forage, limiting their usefulness. That meant supply was mostly over the Great Lakes and up navigable rivers, using cargo ships or "bateaux" -- plural of "bateau", a French term translating literally as "boat", but in frontier terms meaning what amounted to a large flat-bottomed canoe with a mast and square sail. Control of the Great Lakes meant control over the supply lines, though even that avenue for supply was unavailable in the dead of winter, when the lakes froze over.

The actual listed strength of the US Army in June 1812 totaled a little under 12,000 officers and men, but that included roughly 5,000 completely raw new recruits enlisted for additional forces authorized by Congress the preceding January. This was well under the authorized army strength, and the troops were absolutely not prepared for action, in general being poorly led, trained, equipped, and supplied. The Army was logistically dependent on a network of private suppliers, which wasn't necessarily a bad thing in itself, but weak oversight made the scheme vulnerable to incompetence and corruption.

The United States could mobilize much larger numbers of state militia, roughly half a million men. However, although the Republican dislike of standing armies implied a reliance on militia, the state militias were a very uncertain military resource, being even more poorly led, trained, equipped, and supplied than the Army, weapons being scarce and logistical backup almost nonexistent. The militias also were under the control of state governors, and in fact some states specifically refused to allow militia to be used outside their state borders.

The US Navy had a little over 7,000 personnel and 18 ocean-going warships, including the six frigates mentioned earlier; the 32-gun frigate USS ESSEX, and the 28-gun corvette USS ADAMS; plus 10 other warships with 10 to 20 guns. The general condition of the fleet was not the best, with a number of the vessels laid up in the yards; even if they had been in better condition, at the time the Navy didn't have enough sailors to take them all to sea.

America also had large numbers, well over 200, of small gunboats for coastal and harbor defense, most of them constructed from 1807, as tensions with Britain began their steep rise. Jefferson had been very fond of gunboats; and though his gunboats have been bitterly criticized as a waste of money, there was valid reasoning behind them, the gunboats being well-suited to harbor defense, river patrol, and other shallow-water missions, with some authors suggesting that it might have been well to have built more of them. Since the US Navy couldn't really threaten the Royal Navy on the high seas, defenses to repel British attacks on coastal regions were a better use of money than frigates. Lacking the ability to build fortifications to protect every possible coastal town vulnerable to attack, it made more sense to acquire mobile firepower that could be shifted to different localities as needed.

However, the gunboats were obviously useless for blue-water operations, and they were also expensive to maintain: upkeep of ten individual small vessels was more troublesome than upkeep of a single vessel ten times as big. The fact that they could be operated by local authorities made them a good fit to the Jeffersonian distaste for standing military forces, but the lack of control of the Navy over such authorities only complicated the troublesome management of the dispersed gunboat fleet.

The Republicans had no great faith in the Navy, being inclined to rely on "privateers", essentially legalized pirates, private vessels fitted with guns and issued "letters of marque & reprisal" to allow them to raid the seas for "prizes" in the form of ships and their cargoes. Incidentally, US Navy vessels were also allowed to take prizes; in that era, there wasn't a widespread appreciation of the fact that mixing military operations with the profit motive has its drawbacks -- in effect, lowering the priority of high-risk operations of predominantly military utility, and raising the priority of low-risk operations involving financial gain. The profitability of privateering also made it difficult for the Navy to obtain qualified seamen. In addition, privateers were under little or no military control; they were not all that useful for supporting planned military operations, and privateering had a nasty tendency to descend into simple piracy, predation on friend and foe alike.

* With such modest resources, Madison planned to challenge the world's greatest military power. To be sure, war had been brewing for some time, and some preparations had been made -- obtaining new recruits for the Army as mentioned above, with Congress also authorizing the expansion of state militias. The War (Army) Department was modestly reorganized, though administrative staffing remained painfully small. There was no push to build up the Navy, with efforts by interested parties to build up the fleet cut short. Although some Federalists had lobbied to restrict the war to a naval conflict, the general perception was that there was no sense in building up the US Navy, since there was no way it could be made strong enough to really challenge the Royal Navy.

Despite the limitations of US military power, the American people broadly reflected Madison's optimism, knowing that the military imbalance between the US and Britain was only on a global basis. Most of Britain's military resources were tied up fighting Napoleon, with little to spare to put out fires elsewhere; British forces would have to fight across an ocean, resources in Canada being minimal. Jefferson commented that the conquest of Canada would be "a mere matter of marching."

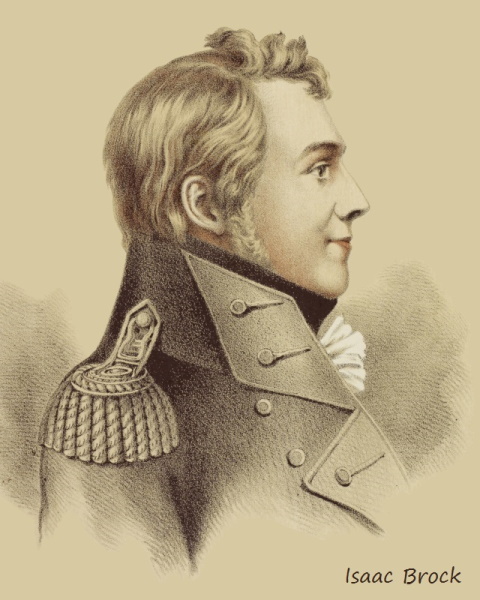

At the outbreak of the war, there were approximately 7,000 British and Canadian regular troops in Upper and Lower Canada. These resources were under the command of Lieutenant General Sir George Prevost, the governor-general of Canada, with Major General Isaac Brock being his lieutenant-general in charge of Upper Canada, where the blow was likely to fall. The British generals knew they could be easily outmatched by the more populous Americans. Royal Navy assets that could be spared to fight the Americans were not much more generous at the time.

Prevost was not the most energetic of senior commanders, partly because he suffered from ill health -- "dropsy", now called "edema", a tendency to build up fluids for a number of unfortunate reasons, leading to a pudgy appearance. Brock, however, had plenty of competence and spine. He was physically imposing and energetically positive, helping to inspire a fighting spirit among Canadians. On the other side of the coin, Madison's failure to unify the USA behind the fight hobbled the war effort at the outset. In the Federalist New England states, public opinion ranged from apathy to active opposition to the war. New Englanders would tend to be bystanders in the conflict, when they weren't actively working against the American war effort.

From a strategic point of view, the most promising invasion route into Canada was by way of Lake Champlain, on the northern section of the border between the states of New York and Vermont, and the Richelieu River, which flowed north from Lake Champlain to join the Saint Lawrence River between Montreal and Quebec City. That meant that the Richelieu River was an avenue straight into the most populous region of Canada; capture Montreal and the Saint Lawrence lifeline would be cut, leaving the British in Upper Canada stranded.

Unfortunately, the fact that New England had no stomach for the war made exploiting the Lake Champlain route troublesome: the New Englanders refused to provide militia to support offensive operations, and would prove consistent in discouraging US government operations in the region. The Northwest, where the threat was worst, enthusiasm for the war ran high, and British forces were weak, offered a seemingly more convenient theater of operations. Besides, since the expectation was that the conquest of Canada would be little more than a walk-over, there was no need to be particularly choosy about what avenues were taken to that end. The Americans chose what they judged to be the cheap and easy route, with the first assaults in Canada delivered from Fort Detroit across the Detroit River, and across the Niagara River on the neck of land between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. They didn't go well.

BACK_TO_TOP* The first American offensive of the war was led by Brigadier General William Hull, a 59-year-old veteran of the Revolutionary War, who had been governor of Michigan Territory and had been booted up to command of the "Northern Department", as it was known in military terms, with the arrival of war. Although Hull had a good military reputation from the Revolution, he was by then not in very good health and lacking energy. Hull was a little too typical of the US Army's high command, which was heavily laden with military fossils left over from the Revolution. A lieutenant colonel named Winfield Scott, then 26 years old and at the beginning of a stellar military career, described the officer corps as dominated by "swaggerers, dependents, decayed gentlemen ... utterly unfit for any military purpose whatsoever." Scott had a very high opinion of himself, but events would prove his judgement entirely accurate.

Hull arrived at Fort Detroit on 5 July 1812, with a force of about 1,500 Ohio militiamen and 300 regulars, which he led across the Detroit river into Canada the next week. The Americans completely outnumbered the forces available to the British in the area, which were mostly concentrated at Fort Malden, about 32 kilometers (20 miles) south down the river. However, Hull's relative numbers of men were misleading: many were sick and more were gradually falling sick, and his supply situation was very tenuous, all the more so because a schooner, the CUYAHOGA, that had been carrying supplies for the force had been seized by the British with a bit of trickery on 2 July.

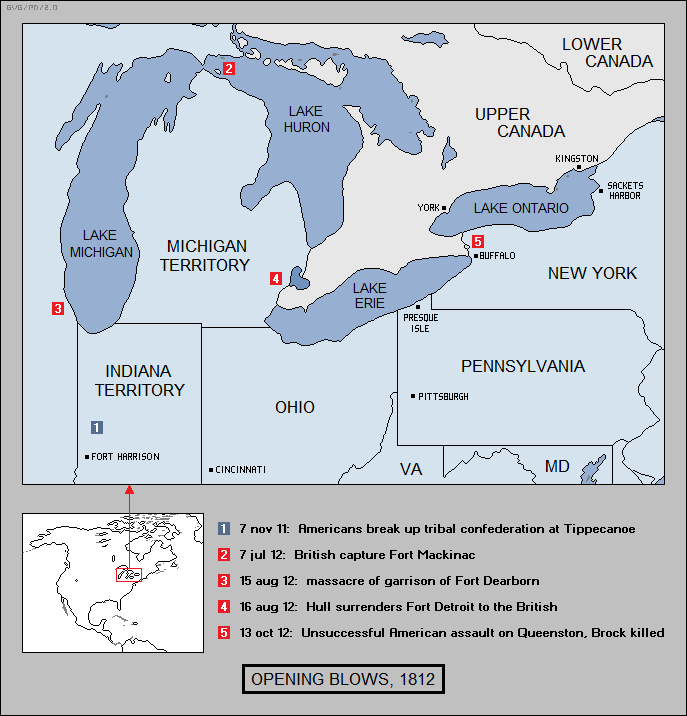

After entering Canada, Hull had neither the strength nor will to do any more than that. General Brock showed no such reluctance to move. He dispatched a small force of his regulars, backed up by fur traders and tribesmen, to Fort Mackinac to the northwest, with the Americans surrendering without a fight on 17 July; Brock moved so fast that the defenders didn't know that war had broken out until the British descended on them. The fort would remain in British hands for the rest of the war. Brock, noting Hull's timidity, sent another group across the Detroit River to cut Hull's supply lines to the south. As Brock might well have expected, Hull took fright and on 7 August pulled his forces back across the river to Fort Detroit. Brock promptly moved his forces up to the river to confront the Americans.

Hull, having become thoroughly spooked, had sent orders to Fort Dearborn to the west, telling the commander to pull out his men and join him. The garrison pulled out on 15 August, to be promptly set upon by a gang of Indians and slaughtered, with the tribesmen then burning the fort. That same day, Brock took Fort Detroit under fire with his artillery from across the river, and the next day, 16 August, he led his forces across to invest the fort. On being warned by Brock that the Indians in British service might not be restrained if the site had to be taken by force, Hull promptly surrendered. Brock released the American militia under "parole", an arrangement in which they were released on the condition that they weren't put back into service. Hull and his regulars ended up as prisoners in Montreal.

Hull was bitterly criticized for his lack of hesitation in surrendering, being accused of cowardice and even treason -- but his men were increasingly ailing, most of his militia had simply gone home, his supply situation was wretched, and he had absolutely no reason to expect that a relief force would be sent to help him out. He also understood that if Fort Detroit were overrun and the Indians were allowed to run riot, as Brock had hinted they would, they would slaughter not only all of his men, but all of the civilians there as well.

Although Hull was entitled to much of the blame for the disaster, there was plenty of blame to spread around in Washington -- though government officials unsurprisingly showed no inclination to admit to fault. Whatever the case, the Americans had thought they would just walk into Canada without difficulty; the actual result was that the US had lost Michigan Territory to the British, given up almost without a fight. The Americans had suffered a painful and largely self-inflicted defeat.

* Tecumseh, who had assisted Brock in his fight against the Americans, was very pleased at the eviction of the Americans, believing the lands now under the British flag could be the basis for an independent or semi-independent Indian nation. Many tribes that had been straddling the fence decided to join the British cause. War parties raided over the Northwest, with some American outposts abandoned and others put under siege, while towns were raided and burned. A force of mounted "volunteers" -- troops raised for Federal service by a state, outside of the normal militia structure -- under Kentucky Congressman Richard M. Johnson managed to drive the war parties out of southern Indiana during September, while other scratch forces came to the relief of forts under siege in the region and raided Indian villages, putting them to the torch. Generally, the inhabitants were able to disappear before the soldiers arrived, but the attacks destroyed shelter and food stores that would be critical for the Indians come the harsh winter.

Brigadier General William Henry Harrison -- as mentioned, governor of Indiana Territory and the hero of the Battle of Tippecanoe -- moved in late September with about 6,500 men in four separated columns to reimpose American control in the Northwest, most importantly to reestablish Fort Detroit. However, the movement bogged down in wet weather, the troops fighting mud, cold, disease, and hunger, and nothing of any real usefulness was accomplished.

General Proctor repatriated Hull in September, it seems on the assumption that he would do more good for the British cause if he were in American hands. Hull would be tried for cowardice, neglect of duty, and treason in early 1814; while the court passed on the treason charge, Hull was found guilty on the other two counts and sentenced to be shot by a firing squad -- making him the only American general ever to be condemned to death by a court-martial. However, a recommendation was added that he be given clemency, due to his Revolutionary War service and his age. Madison commuted the sentence to dismissal from the army.

BACK_TO_TOP* While Hull's offensive, such as it was, into Canada was coming to ruin, there were minor engagements along the northern borders of New York state. With the outbreak of war, the US Navy began to build up a base at Sackets Harbor, at the northeast corner of Lake Ontario not far from where the Saint Lawrence flowed from the lake. The British "Provincial Marine" fleet, based at Kingston on the other side of the lake's outlet to the Saint Lawrence, descended on Sackets Harbor on 21 July, resulting in a noisy expenditure of ammunition on both sides that did no one much injury, with the British finally deciding the exercise was more bother than it was worth and withdrawing.

Come the end of August, US Navy Captain Isaac Chauncey was assigned to take command Sackets Harbor, with a directive to take command of the fleet on Lake Ontario and build up naval forces to counter the British. Chauncey didn't actually arrive at Sackets Harbor for a few months, spending the interim in setting up a supply system and putting in motion work on the modification of available merchantmen to warships and construction of new warships, the work being assigned to a Scots-born shipwright named Henry Eckford. The converted merchantmen had never been designed to carry armament on their decks, and so they tended to be dangerously topheavy.

A parallel effort was underway to establish a fleet on Lake Erie, initially operating from Black Rock, north of Buffalo near the lake's outlet to the Niagara river. Later in the year, the focus of US Navy efforts on Lake Erie shifted to the southwest shore of the lake, at Presque Isle -- now Erie, Pennsylvania. The efforts on the two lakes were not closely coordinated, Chauncey seeing the construction of the Lake Erie fleet as a competitor for resources in his effort to take control of Lake Ontario.

Chauncey's effort was paralleled by the commandant the Royal Navy had assigned to Kingston, Admiral Sir James Yeo, who began his own intensive shipbuilding operations at Kingston and at York, the provincial capital -- previously and later known as Toronto -- on the northwest corner of Lake Ontario. How competent Chauncey and Yeo were remains arguable; events would show neither was particularly aggressive, though that was much less of a problem for Yeo, since his strategy was basically defensive.

In any case, there were no serious clashes between the two lake fleets during 1812. The most significant action wasn't a naval action, instead being a raid by American sailors, backed up by US Army soldiers, against Fort Erie -- on the west short of the entrance of Lake Erie to the Niagara river. The raiders captured one Provincial Marine ship, the CALEDONIA, and burned another, the DETROIT. The loss of the vessels was bad enough for the British, but they had also been loaded with desperately needed supplies.

* In the meantime, Major General Henry Dearborn -- another Revolutionary War veteran, once a secretary of war -- was demonstrating very little initiative. Instead of launching an offensive in parallel with Hull's, Dearborn spent his time recruiting men and building up coastal defenses. New York Governor Daniel Tompkins, who wanted something done, appointed Stephen van Rensselaer, a member of a socially prominent family and one of the biggest landowners in New York, as a major general in charge of the New York militia. Van Rensselaer took a force of about 3,000 militia and regulars to Lewiston, towards the north end of the Niagara River below Fort Niagara, in preparation for a move across against Queenston on the opposite bank.

Van Rensselaer had no military background, but at least he was willing to fight -- which was well more than what could be said about his army counterpart, Brigadier General Alexander Smyth, in command of about 2,000 troops at Buffalo. Van Rensselaer and Smyth couldn't stand the sight of each other and wouldn't cooperate; neither felt that they could count on any support from the army higher command or the government in Washington DC -- which, given the often careless direction of the war to that time, was clearly a sensible judgement.

Lack of preparation and resources prevented any serious operations of American forces on the Niagara frontier until October. Brock had shifted his forces to there after defeating Hull and was prepared for a crossing. Smyth having refused to support a move against Queenston, van Rensselaer decided to go it alone, being prodded to a considerable extent by the fact that many of his militia were so weary of waiting for something to happen that they were threatening to go home unless he took action.

Van Rensselaer's troops rowed across the Niagara River on the morning of 13 October 1812 to seize the commanding Queenston Heights over the river. Although many of the militia refused to cross, saying nobody could order then to leave American soil, the assault went well at first, with the invaders seizing the heights. Brock hastily threw together a counterattack; given his experience with Hull and his ragtag force, Brock believed that if he simply charged, the Americans would scatter. Brock was overconfident; the attack was thrown back, and he was killed by a musket ball. The American force, now about 600 strong and under the command of Winfield Scott, consolidated its position on the heights.

However, the defenders received reinforcements and Major General Roger Sheaffe, who had moved into Brock's place, more methodically organized a second counterattack. The Americans fought back hard, but they were outmatched; Scott finally surrendered with his force. British losses in killed and wounded were a fraction of those of the Americans.

Van Rensselaer, who as a prominent Federalist proved a magnetic target for criticism by the Republican newspapers, resigned three days after the battle, leaving Smyth in charge of the frontier forces, with a directive from Dearborn to take the offensive. Smyth demanded reinforcement from the War Department and got it, to the extent that such was available -- only to do little but issue proclamations, with his militia gradually melting away. The troops were miserably clothed, housed, and fed; they tore down fences for firewood, and stole edibles from local farms. There was only so much pointless hardship the men were willing to put up with before they simply walked off.

After inconclusive probes across the Niagara against Fort Erie in late November, with no more result than to get a few scores of men on both sides killed and wounded, Smyth's regulars went into winter quarters at the end of November, halting all pretense of action for the season. The only thing Smyth accomplished for his efforts was to earn the disgust of his men and produce bitter disputes with his subordinates. One of them, Brigadier General Peter Porter, whose contributions to the campaign consisted mostly of quarrels, called Smyth a coward, leading to a duel between the two men; a historian later dryly commented: "Unfortunately, both missed." Smyth then requested leave to visit his family, with the request quickly granted; the Army then quietly decided not to call him back to duty and dropped him from the rolls. He later became a congressman from Virginia.

* Dearborn actually had the biggest force in the region, based at Albany on the eastern side of the state. In principle, Dearborn was to lead his troops north to Montreal in collaboration with the push across the Niagara River, but he did nothing as van Rensselaer took a thrashing at Queenston. In early November, in response to insistent badgering by Secretary of War William Eustis, Dearborn led a force north to Plattsburg, on Lake Champlain, intending to then march into Canada, but on crossing the border his advance guard ran into resistance. His militia refused to cross the border and Dearborn, having lost what little steam he had, simply put his men into winter quarters at Plattsburg. An observer commented that the exercise had been "a miscarriage without even [the] heroism of disaster."

And so ended American military activity in the north for the year of 1812 -- with a record dominated by failures, thanks to the incompetence and timidity of US Army officers. The only American commander who demonstrated any spine was van Rensselaer, and he was militia; being a Federalist, the only reward he got for his efforts from the Republican leadership was to blame him for much of what had gone wrong. Brock had demonstrated tough and competent leadership, at the expense of his own life; he was lionized as a hero by Canadians. He was replaced as lieutenant governor of Upper Canada by Sheaffe.

* Incidentally, the Battle of Queenston led to a confrontation between Britain and America over treatment of prisoners. Just as with seamen who the Royal Navy impressed, the British were inclined to regard any soldier they captured as a British-born citizen as still British. One American soldier in British hands recollected an exchange between a British soldier and another American prisoner of Irish origins, with the soldier insisting the prisoner was an Irishman and the prisoner countering just as insistently he was not, saying he had been born in Pennsylvania. The soldier then demanded: "And do they make Irishmen in Pennsylvania?"

The prisoner replied: "And truly they do -- we have a rapid machine there that turns out Irishmen by the dozen."

Unfortunately, to the extent there was any humor in the situation, the prisoner knew perfectly well the joke was on him. At Queenston, the British identified 23 of the prisoners, most of them Irishmen, as British subjects. They were shipped them off to England in chains to stand trial of treason, a charge for which they of course faced execution. Winfield Scott protested to the British, but they ignored him; after he was exchanged back into American hands, he went to Washington and raised hell about the issue. Madison ordered that an equivalent number of British prisoners in American custody be placed under close confinement, and made it publicly clear what would happen to these unfortunate pawns if their American counterparts in British hands were executed.

Even though such a response might have been expected by the sensible, British papers howled with rage at American "injustice", and some Federalists were inclined to side with the British on the matter. Fortunately, although the tension over treatment of American prisoners captured by the British and labeled "traitors" lingered through the war, the British decided against starting a hanging contest. Unfortunately, as a rule neither side was all that humane in its treatment of prisoners, often keeping them locked up under wretched conditions. The cruelties were well more due to lack of resources, incompetence, and indifference than active malice -- but the end result was still exchanges of bitter accusations and denunciations.

BACK_TO_TOP* The contrast between the conduct of the US Army and the US Navy in 1812 could not have been greater, with the Navy demonstrating great dash on the high seas. While the Republicans had neglected the Navy as much as the Army, it had good officers with substantial combat experience -- in the Quasi-War and the fight against the Barbary Pirates -- who kept their crews drilled and disciplined. Madison hadn't figured that America's little Navy could do much but commit suicide in a stand-up fight with the Royal Navy, and so the administration's orders to the Navy were conservative, even timid, the general idea being that the best use of the Navy's warships was in coastal and harbor defense.

The Royal Navy's obvious strategy would be to shut down American trade and bottle up American warships in harbor -- but though the Royal Navy was overwhelmingly superior to the US Navy on a global basis, once again most of the British fleet was committed to the fight against Napoleon. Vice-Admiral Herbert Sawyer of the Royal Navy, residing at the base at Halifax, Nova Scotia, had only a few dozen warships available to him, hardly enough to establish and enforce a blockade along the extended American coast.

There was also the fact that British forces in Spain were heavily dependent on foodstuffs shipped from New England, for the time being both the British and, over Madison's objections, the Americans overtly supported that particular trade -- Sawyer generously granted shipping licenses to New England merchantmen, while American customs officials pulled in revenue from the trade. At the outset, Sawyer's instructions also specifically discouraged aggressiveness, it seems on the assumption that the fuss between the two countries was likely to blow over quickly, there being some thinking in Britain that the Americans would cool off once they learned of the revocation of the Orders in Council. That, however, was clearly underestimating the depths of American resentment over impressment, a matter on which the British government had not the slightest intention of budging.

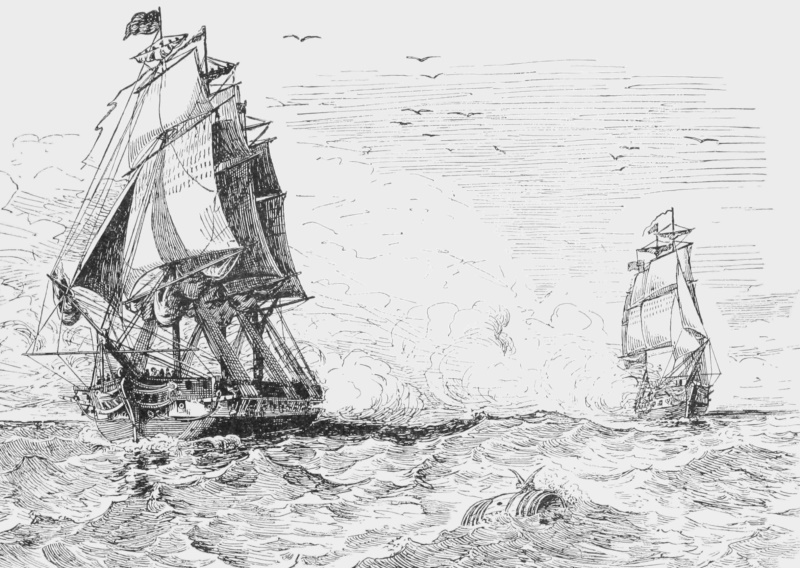

In sum, for the moment the Royal Navy was hobbled by lack of resources and political restraint from bringing its full weight to bear on America. Under such conditions, the US Navy's officers saw an opportunity for glory, deciding to ignore the wafflings of their own government and take action. As soon as Commodore John Rodgers, the most senior US Navy officer and in charge of a flotilla at New York City, got news of the outbreak of war, he got his warships to sea, including the frigates USS PRESIDENT, UNITED STATES, and CONGRESS; the sloop HORNET; and the brig ARGUS. Rodgers intended to escape before he could be bottled up by the Royal Navy and strike against British shipping in the western Atlantic sea lanes.

Rodgers' exercise was unproductive, yielding no great volume of prizes before Rodgers docked again in Boston in late August. The Royal Navy had belatedly stationed a powerful squadron of warships outside New York harbor to intercept the American warships when they came home, but Rodgers proved unpredictable. Getting home intact was an accomplishment, but the failure to score against the British was a frustration.

Other US Navy commanders had better luck. The USS ESSEX, under the command of Captain David Porter, hadn't been ready to go to sea at the outbreak of the war, finally departing New York harbor in early July. The ESSEX captured a series of merchantmen and, on 13 August, defeated the smaller 20-gun Royal Navy sloop HMS ALERT. By the time the ESSEX returned to Delaware Bay in September, the warship had captured nine prizes.

The USS CONSTITUTION, under the command of 39-year-old Captain Isaac Hull -- a nephew of General William Hull -- had been refitting at Annapolis, Maryland when the war broke out, and the vessel didn't go to sea until mid-July. After various adventures, Hull made headlines when the CONSTITUTION defeated the 38-gun Royal Navy frigate GUERRIERE in the Atlantic west of Boston on 19 August 1812. The Americans had a particular grudge against the GUERRIERE; as mentioned the USS PRESIDENT having attempted to hunt it down the year before, only to engage the HMS LITTLE BELT by mistake. The GUERRIERE's cannonballs were said to have bounced off the sturdy hull of the CONSTITUTION, leading to the nickname of "Old Ironsides" -- she's still in service incidentally, if as a museum, although she still puts to sea on occasion. It was the most visible defeat of the Royal Navy since 1803 and the British were extremely upset, newspapers claiming it would make the Americans "insolent and confident." They already were.

* By that time, the Royal Navy was beginning to realize that greater exertions were required, taking an organizational step towards a unified force in American waters in mid-August by combining forces based in Halifax and in the West Indies, placing them under the command of Vice Admiral Sir John Warren. He was well senior to Sawyer, who was relieved of his post in the shuffle; Warren was a very experienced officer, possibly too experienced in that he was clearly getting too old for the job. Warren was empowered to discuss peace with the Americans on the basis of "status quo ante bellum", with his brief of course allowing him to conduct local discussions along such lines. He clearly recognized the dissatisfaction of the New England states with the war and hoped to encourage it, continuing to practice of granting licenses to New England's shipping.

In the meantime, the Americans were refining their own naval strategy. Navy Secretary Paul Hamilton was not notably competent at his job, but he did realize that sending out the US Navy fleet as a unit wasn't a good idea; it didn't provide very good sea coverage, and it left the Navy vulnerable to being wiped out in one stroke by superior Royal Navy squadrons. After the return of Rodgers' squadron, Hamilton decided to divide the blue-water force into three "cruising squadrons", each composed of two or three ships that could operate as a group or independently in their own oceanic region:

Ranging wide over the Atlantic, US Navy warships scored other victories. On 25 October 1812, the crew of the USS UNITED STATES, under Decatur, encountered the HMS MACEDONIAN in the Atlantic south of the Azores; in the following shootout, the UNITED STATES demasted the MACEDONIAN, forcing its surrender. When Decatur boarded the MACEDONIAN after the British vessel had struck its colors, he found "fragments of dead scattered in every direction, the decks slippery with blood, one continuous agonizing yell of the unhappy wounded." He found the scene "deprived me very much of the pleasure of victory" -- and gallantly refused to accept the captain's sword.

Decatur performed quick repairs on the captured vessel, and a prize crew sailed it back to Newport, Rhode Island. There, it was refitted and put into US Navy service as the USS MACEDONIAN. The US government awarded the officers and men of the USS UNITED STATES $200,000 in prize money, a huge fortune at the time.

The CONSTITUTION, now under the command of Bainbridge, scored another victory over the Royal Navy on 29 December 1812, defeating the HMS JAVA in the Atlantic off the coast of Brazil after a protracted and vicious fight in which Bainbridge was wounded twice and the British captain, Henry Lambert, killed. The JAVA surrendered, but the vessel was so badly damaged that Bainbridge ordered her burned. The CONSTITUTION was far from unharmed itself, and so Bainbridge had to sail home for refit.

The Americans did suffer losses at sea in 1812, of course. The 16-gun brig USS NAUTILUS was captured in July, a short time after the declaration of war, while the revenue cutter USS JAMES MADISON was taken in August and the US Navy schooner USS VIXEN was captured in November. However, for the moment, the score card between the US Navy and the Royal Navy was against the British, with a great outcry in Britain over such humiliations.

* The duels between US Navy and Royal Navy ships made for exciting headlines, but the privateers conducted the real naval war at the time, ranging widely and seizing hundreds of British merchantmen. As with the US Navy, the ships of the privateers were first-class, typically of the "Baltimore schooner" configuration, with a single mast and a fore-aft rigged sail; they were lightly armed, but all they had to do was outfight merchantmen, since they could generally outrun Royal Navy warships.

Still, nobody with sense on either side had any doubt that the Royal Navy was dominant on the high seas. The Americans were simply taking advantage of Britain's distraction with Napoleon and not doing much more than making a nuisance of themselves; once the Royal Navy was able to focus its attention on America, Britain would reassert its control of the oceans. The US Navy would continue to challenge the Royal Navy and with success, but there was no hope of the Americans affecting the strategic balance on the oceans in the slightest.

* However, through 1812 the Americans were doing well for themselves at sea, tweaking the Royal Navy, which hadn't been able -- or, given the peculiar blind eye turned by both sides toward trade with New England, entirely willing -- to set up an effective blockade and sweep up American merchantmen returning to home ports at the outbreak of war, resulting in a windfall of customs duties for the cash-strapped government. In fact, the Navy's feats were impressive enough to overshadow the setbacks on land in the headlines.

BACK_TO_TOP