* In the last chapter of THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES, Darwin reviewed his argument and wrote up his conclusions, suggesting that his work would prove highly relevant to future studies in the biological sciences.

* In chapter 14, Darwin provides a summary of his concepts:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

As this whole volume is one long argument, it may be convenient to the reader to have the leading facts and inferences briefly recapitulated.

END_QUOTE

Darwin began by admitting that his notion of evolution by natural selection might seem implausible on first sight, but suggested that a careful examination of the facts showed otherwise:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

That many and grave objections may be advanced against the theory of descent with modification through natural selection, I do not deny. I have endeavoured to give to them their full force. Nothing at first can appear more difficult to believe than that the more complex organs and instincts should have been perfected, not by means superior to, though analogous with, human reason, but by the accumulation of innumerable slight variations, each good for the individual possessor. Nevertheless, this difficulty, though appearing to our imagination insuperably great, cannot be considered real if we admit the following propositions, namely:

The truth of these propositions cannot, I think, be disputed. It is, no doubt, extremely difficult even to conjecture by what gradations many structures have been perfected [...] but we see so many strange gradations in nature, as is proclaimed by the canon, "Natura non facit saltum [Nature does not make jumps]" that we ought to be extremely cautious in saying that any organ or instinct, or any whole being, could not have arrived at its present state by many graduated steps.

END_QUOTE

He went on to review some of the more troublesome objections. After discussing hybrids, Darwin re-examined biogeography, saying that apparent spottiness in the distribution of certain species presented challenges, but that the challenges were by no means fatal:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

Turning to geographical distribution, the difficulties encountered on the theory of descent with modification are grave enough. All the individuals of the same species, and all the species of the same genus, or even higher group, must have descended from common parents; and therefore, in however distant and isolated parts of the world they are now found, they must in the course of successive generations have passed from some one part to the others. We are often wholly unable even to conjecture how this could have been effected.

Yet, as we have reason to believe that some species have retained the same specific form for very long periods, enormously long as measured by years, too much stress ought not to be laid on the occasional wide diffusion of the same species; for during very long periods of time there will always be a good chance for wide migration by many means. A broken or interrupted range may often be accounted for by the extinction of the species in the intermediate regions. It cannot be denied that we are as yet very ignorant of the full extent of the various climatal and geographical changes which have affected the earth during modern periods; and such changes will obviously have greatly facilitated migration.

END_QUOTE

As far as the requirement for intermediate forms went, Darwin also acknowledged a challenge -- but still did not see it as fatal:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

As on the theory of natural selection an interminable number of intermediate forms must have existed, linking together all the species in each group by gradations as fine as our present varieties, it may be asked, Why do we not see these linking forms all around us? Why are not all organic beings blended together in an inextricable chaos?

END_QUOTE

While Darwin did not, in spite of all his extended considerations of hybridization, have a deep grasp of processes of speciation, he did understand that evolution implied populations acquiring adaptations that would help them push less well adapted competitors to the side, "so that the intermediate varieties will, in the long run, be supplanted and exterminated."

That of course led to the question: "Why is not every geological formation charged with such links? Why does not every collection of fossil remains afford plain evidence of the gradation and mutation of the forms of life?"

He had to fall back on the limitations of the fossil record: "I can answer these questions and grave objections only on the supposition that the geological record is far more imperfect than most geologists believe." Given the sketchy collections of fossils available in 1859, at least in comparison to the present day, Darwin had every reason to find the record imperfect, and no doubt would be pleased to see how much more we have learned since his time.

Having reviewed the weaknesses of his theory, Darwin then focused on the positive evidence in its favor, starting with artificial selection:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

Under domestication we see much variability [in animals and plants]. This seems to be mainly due to the reproductive system being eminently susceptible to changes in the conditions of life; so that this system, when not rendered impotent, fails to reproduce offspring exactly like the parent-form. [...]

There is much difficulty in ascertaining how much modification our domestic productions have undergone; but we may safely infer that the amount has been large, and that modifications can be inherited for long periods. As long as the conditions of life remain the same, we have reason to believe that a modification, which has already been inherited for many generations, may continue to be inherited for an almost infinite number of generations.

On the other hand we have evidence that variability, when it has once come into play, does not wholly cease; for new varieties are still occasionally produced by our most anciently domesticated productions.

Man does not actually produce variability; he only unintentionally exposes organic beings to new conditions of life, and then nature acts on the organisation, and causes variability. But man can and does select the variations given to him by nature, and thus accumulate them in any desired manner. He thus adapts animals and plants for his own benefit or pleasure.

He may do this methodically, or he may do it unconsciously by preserving the individuals most useful to him at the time, without any thought of altering the breed. It is certain that he can largely influence the character of a breed by selecting, in each successive generation, individual differences so slight as to be quite inappreciable by an uneducated eye. This process of selection has been the great agency in the production of the most distinct and useful domestic breeds.

END_QUOTE

Of course, if organisms are variable and their forms can be altered by human selection, there was no obstacle to thinking that nature could perform selection as well:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

There is no obvious reason why the principles which have acted so efficiently under domestication should not have acted under nature. In the preservation of favoured individuals and races, during the constantly-recurrent Struggle for Existence, we see the most powerful and ever-acting means of selection.

The struggle for existence inevitably follows from the high geometrical ratio of increase which is common to all organic beings. [...] More individuals are born than can possibly survive. [...] The slightest advantage in one being, at any age or during any season, over those with which it comes into competition, or better adaptation in however slight a degree to the surrounding physical conditions, will turn the balance [between survival and extinction].

END_QUOTE

Darwin carefully pointed out that simple survival was not the only criteria involved in natural selection -- there was also the issue of procreation, leading to the factor of sexual selection in evolution:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

With animals having separated sexes there will in most cases be a struggle between the males for possession of the females. The most vigorous individuals, or those which have most successfully struggled with their conditions of life, will generally leave most progeny. But success will often depend on having special weapons or means of defence, or on the charms of the males; and the slightest advantage will lead to victory.

END_QUOTE

Darwin saw nothing at all outrageous in his concept of natural selection:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

If then we have under nature variability and a powerful agent always ready to act and select, why should we doubt that variations in any way useful to beings, under their excessively complex relations of life, would be preserved, accumulated, and inherited? Why, if man can by patience select variations most useful to himself, should nature fail in selecting variations useful, under changing conditions of life, to her living products?

What limit can be put to this power, acting during long ages and rigidly scrutinising the whole constitution, structure, and habits of each creature -- favouring the good and rejecting the bad? I can see no limit to this power, in slowly and beautifully adapting each form to the most complex relations of life. [...]

As each species tends by its geometrical ratio of reproduction to increase inordinately in number; and as the modified descendants of each species will be enabled to increase by so much the more as they become more diversified in habits and structure, so as to be enabled to seize on many and widely different places in the economy of nature, there will be a constant tendency in natural selection to preserve the most divergent offspring of any one species.

Hence during a long-continued course of modification, the slight differences, characteristic of varieties of the same species, tend to be augmented into the greater differences characteristic of species of the same genus. New and improved varieties will inevitably supplant and exterminate the older, less improved and intermediate varieties; and thus species are rendered to a large extent defined and distinct objects.

END_QUOTE

Darwin saw natural selection at work in the displacement of local organisms by what we would now call "invasive species":

BEGIN_QUOTE:

As natural selection acts by competition, it adapts the inhabitants of each country only in relation to the degree of perfection of their associates; so that we need feel no surprise at the inhabitants of any one country, although on the ordinary view supposed to have been specially created and adapted for that country, being beaten and supplanted by the naturalised productions from another land.

END_QUOTE

-- in the clear imperfection of many biological adaptations:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

Nor ought we to marvel if all the contrivances in nature be not, as far as we can judge, absolutely perfect; and if some of them be abhorrent to our ideas of fitness. We need not marvel at the sting of the bee causing the bee's own death; at drones being produced in such vast numbers for one single act, and being then slaughtered by their sterile sisters; at the astonishing waste of pollen by our fir-trees; at the instinctive hatred of the queen bee for her own fertile daughters; at [parasitic wasp larvae] feeding within the live bodies of caterpillars; and at other such cases. The wonder indeed is, on the theory of natural selection, that more cases of the want of absolute perfection have not been observed.

END_QUOTE

-- in the presence of vestigial organs:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

In both varieties and species, use and disuse seem to have produced some effect; for it is difficult to resist this conclusion when we look, for instance, at the logger-headed duck, which has wings incapable of flight, in nearly the same condition as in the domestic duck; or when we look at the burrowing tucutucu, which is occasionally blind, and then at certain moles, which are habitually blind and have their eyes covered with skin; or when we look at the blind animals inhabiting the dark caves of America and Europe.

END_QUOTE

-- and in what are now known as "genetic throwbacks" in modern species:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

In both varieties and species reversions to long-lost characters occur. How inexplicable on the theory of creation is the occasional appearance of stripes on the shoulder and legs of the several species of the horse-genus and in their hybrids! How simply is this fact explained if we believe that these species have descended from a striped progenitor, in the same manner as the several domestic breeds of pigeon have descended from the blue and barred rock-pigeon!

END_QUOTE

He saw no serious challenge to his ideas in the evolution of elaborate instinctive behaviors:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

Glancing at instincts, marvellous as some are, they offer no greater difficulty than does corporeal structure on the theory of the natural selection of successive, slight, but profitable modifications.

END_QUOTE

While again acknowledging that the geological record was imperfect, Darwin pointed out that what was known supported his ideas:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

[Such] facts as the record gives, support the theory of descent with modification. New species have come on the stage slowly and at successive intervals; and the amount of change, after equal intervals of time, is widely different in different groups. The extinction of species and of whole groups of species, which has played so conspicuous a part in the history of the organic world, almost inevitably follows on the principle of natural selection; for old forms will be supplanted by new and improved forms. Neither single species nor groups of species reappear when the chain of ordinary generation has once been broken.

The gradual diffusion of dominant forms, with the slow modification of their descendants, causes the forms of life, after long intervals of time, to appear as if they had changed simultaneously throughout the world. The fact of the fossil remains of each formation being in some degree intermediate in character between the fossils in the formations above and below, is simply explained by their intermediate position in the chain of descent.

The grand fact that all extinct organic beings belong to the same system with recent beings, falling either into the same or into intermediate groups, follows from the living and the extinct being the offspring of common parents. As the groups which have descended from an ancient progenitor have generally diverged in character, the progenitor with its early descendants will often be intermediate in character in comparison with its later descendants; and thus we can see why the more ancient a fossil is, the oftener it stands in some degree intermediate between existing and allied groups.

END_QUOTE

In these comments, Darwin revealed a bit of Victorian prejudice, mentioning "new and improved" forms of organisms. Obviously he meant "improved" in the sense of "better adapted to the environment", but modern sensibilities are more cautious in suggesting that evolution has any "direction" other than improved adaptation to environment. In any case, he went on to point out that the geographical distribution of organisms was another item in favor of his ideas:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

[The] law of the long endurance of allied forms on the same continent -- of marsupials in Australia, of edentata in America, and other such cases -- is intelligible, for within a confined country, the recent and the extinct will naturally be allied by descent.

[If] we admit that there has been during the long course of ages much migration from one part of the world to another, owing to former climatal and geographical changes and to the many occasional and unknown means of dispersal, then we can understand, on the theory of descent with modification, most of the great leading facts in Distribution. [...] We see the full meaning of the wonderful fact, which must have struck every traveller, namely, that on the same continent, under the most diverse conditions, under heat and cold, on mountain and lowland, on deserts and marshes, most of the inhabitants within each great class are plainly related; for they will generally be descendants of the same progenitors and early colonists. [...]

Although two areas may present the same physical conditions of life, we need feel no surprise at their inhabitants being widely different, if they have been for a long period completely separated from each other; for as the relation of organism to organism is the most important of all relations, and as the two areas will have received colonists from some third source or from each other, at various periods and in different proportions, the course of modification in the two areas will inevitably be different.

On this view of migration, with subsequent modification, we can see why oceanic islands should be inhabited by few species, but of these, that many should be peculiar. We can clearly see why those animals which cannot cross wide spaces of ocean, as frogs and terrestrial mammals, should not inhabit oceanic islands; and why, on the other hand, new and peculiar species of bats, which can traverse the ocean, should so often be found on islands far distant from any continent. Such facts as the presence of peculiar species of bats, and the absence of all other mammals, on oceanic islands, are utterly inexplicable on the theory of independent acts of creation.

END_QUOTE

To Darwin, evolution by natural selection made sense of the familial relationships of organisms where there had been no real sense before:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

The fact, as we have seen, that all past and present organic beings constitute one grand natural system, with group subordinate to group, and with extinct groups often falling in between recent groups, is intelligible on the theory of natural selection with its contingencies of extinction and divergence of character.

END_QUOTE

That tree of familial relationships was evident in the similarities of biostructures between organisms, with improvisations of common structures to different ends:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

The framework of bones being the same in the hand of a man, wing of a bat, fin of the porpoise, and leg of the horse -- the same number of vertebrae forming the neck of the giraffe and of the elephant -- and innumerable other such facts, at once explain themselves on the theory of descent with slow and slight successive modifications.

The similarity of pattern in the wing and leg of a bat, though used for such different purpose -- in the jaws and legs of a crab -- in the petals, stamens, and pistils of a flower, is likewise intelligible on the view of the gradual modification of parts or organs, which were alike in the early progenitor of each class.

END_QUOTE

It was also demonstrated in the similarities between embryos of widely-different animals, with the embryos of some demonstrating what could only be reasonably interpreted as ancestral features:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

On the principle of successive variations not always supervening at an early age, and being inherited at a corresponding not early period of life, we can clearly see why the embryos of mammals, birds, reptiles, and fishes should be so closely alike, and should be so unlike the adult forms. We may cease marvelling at the embryo of an air-breathing mammal or bird having branchial slits and arteries running in loops, like those in a fish which has to breathe the air dissolved in water, by the aid of well-developed branchiae.

END_QUOTE

Darwin, having reviewed his evidence, stated that he felt his ideas were justified, but knew that there was considerable resistance to them:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

Although I am fully convinced of the truth of the views given in this volume under the form of an abstract, I by no means expect to convince experienced naturalists whose minds are stocked with a multitude of facts all viewed, during a long course of years, from a point of view directly opposite to mine. It is so easy to hide our ignorance under such expressions as the "plan of creation," "unity of design," etc., and to think that we give an explanation when we only restate a fact. Any one whose disposition leads him to attach more weight to unexplained difficulties than to the explanation of a certain number of facts will certainly reject my theory.

END_QUOTE

Darwin expressed hope that more open-minded naturalists, in particular the younger generation, would be more receptive to his ideas. That would turn out to be true over the long run, but it is hard to believe that he had any idea of how stubborn resistance to his notions would prove outside of the scientific community, how long he what called the "curious illustration of the blindness of preconceived opinion" would persist.

Darwin saw his theory not as a mere examination of details but as a synthesis of general principles, speaking prophetically but as usual cautiously:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

I believe that animals have descended from at most only four or five progenitors, and plants from an equal or lesser number. Analogy would lead me one step further, namely, to the belief that all animals and plants have descended from some one prototype. But analogy may be a deceitful guide. Nevertheless, all living things have much in common, in their chemical composition, [...] their cellular structure, and their laws of growth and reproduction. [...] Therefore I should infer from analogy that probably all the organic beings which have ever lived on this earth have descended from some one primordial form, into which life was first breathed.

END_QUOTE

Darwin was bold enough, and perfectly correct, to also see his theory as providing a unifying principle for biology, writing eloquently:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

The other and more general departments of natural history will rise greatly in interest. The terms used by naturalists of affinity, relationship, community of type, paternity, morphology, adaptive characters, rudimentary and aborted organs, etc., will cease to be metaphorical, and will have a plain signification. When we:

When we thus view each organic being, how far more interesting, I speak from experience, will the study of natural history become! A grand and almost untrodden field of inquiry will be opened, on the causes and laws of variation, on correlation of growth, on the effects of use and disuse, on the direct action of external conditions, and so forth. The study of domestic productions will rise immensely in value. A new variety raised by man will be a far more important and interesting subject for study than one more species added to the infinitude of already recorded species. Our classifications will come to be, as far as they can be so made, genealogies; and will then truly give what may be called the plan of creation.

END_QUOTE

He even hinted that his theory would have application in the then-emerging field of psychology, and suggested that science would learn more about human origins -- which is incidentally about all Darwin said about the subject in THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

In the distant future I see open fields for far more important researches. Psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation. Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.

END_QUOTE

Darwin continued in an eloquent vein in his closing comments, suggesting how his ideas underlay the complicated network of interactions between organisms, what we would today call "ecology":

BEGIN_QUOTE:

It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us.

These laws, taken in the largest sense, being:

Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows.

END_QUOTE

Darwin famously concluded:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

END_QUOTE

BACK_TO_TOP* Charles Darwin tends to have an unusually prominent stature in the field of biology, as compared to scientists in other domains. Newton's prominence in physics tends to rival the stature of Darwin, though Newton shares the stage with Einstein; but it is hard to think of rivals to Darwin in the field of biology, or for that matter in, say, astronomy, geology, or chemistry. Lavoisier might be a towering figure in the history of chemistry, but few but chemists have heard of him.

Darwin's prominence is due to his construction of a far-reaching vision that transformed biology from a study that was maybe only a bit more sophisticated than stamp-collecting -- involving the collection and cataloging of observations and details -- into a science with a framework into which those observations and details could be integrated. What Darwin achieved was effectively a "grand unified theory" of biology, not merely by identifying central themes of the science, but with his fussy thoroughness in proclaiming his ignorance, pointing out parts of the framework that needed to be filled in later by others.

Darwin is completely entitled to his fame, but it has downsides. It tends to focus controversy over modern evolutionary theory (MET) on what he said or meant. That can be something of a backwards exercise, partly because the attitudes and idiosyncrasies of a middle-class Victorian gentleman are not all that relevant today, and more so because MET has advanced a great deal on what Darwin could say. In fact, it has advanced so much that his original ideas amount to not much more than an initial rough sketch of what would later emerge. That sketch was also clearly wrong in some details, though it is staggering to see just how much Darwin got right -- the man was a genius, there's no honest doubt of it. Still, sometimes the dispute over Darwin himself seems about as absurd as would be focusing all discussion in aviation on what the Wright Brothers said or did.

The dispute is there, and so it is useful to outline and review his core ideas from THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES just to know exactly what Darwin did or did not say. I wrote this document to clarify to myself what Darwin said, which is not entirely easy to determine because I find THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES, with its Victorian prose and extended discussions of observations of 19th-century naturalists, something of a dry and intimidating read.

As far as readers go, this document is focused on two target audiences:

I have to emphasize that I have no particular qualifications in biology and that, though I am a student of Darwin, I am by no means a Darwin scholar. My misunderstandings may show in places. Hopefully, any defects can be corrected in future releases of this document. I must also warn that, though I haven't altered Darwin's verbiage in the citations here asides from cuts, I have in some cases edited the punctuation to make the citations easier to read.

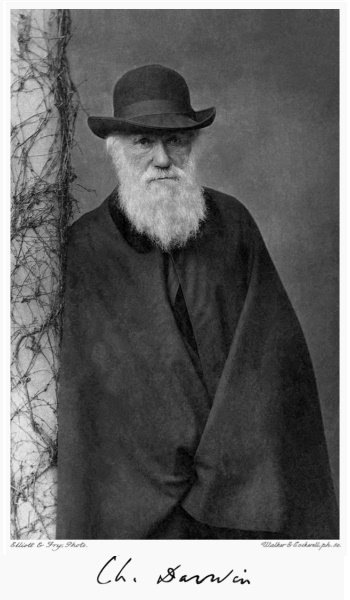

* Illustrations credits:

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 apr 09 / Released as THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES: AN OUTLINE v1.0.1 / 01 nov 09 / Review & polish. v1.0.2 / 01 jun 10 / Quick cleanup. v1.1.0 / 01 may 11 / Tweaks inspired by John Whitfield's blog. v1.1.1 / 01 may 13 / Review & polish. v1.2.0 / 01 apr 15 / Multiple small enhancements. v2.0.0 / 01 mar 17 / Changed to THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES REVISITED. v2.0.1 / 01 feb 19 / Review & polish. v2.0.2 / 01 jan 21 / Review & polish. v2.1.0 / 01 nov 22 / Illustrations update. v2.1.1 / 01 jul 24 / Illustrations update.

I actually released a "v0.0.0" document at the beginning of 2009, but it was strictly a brief stub, intended to attract the attention of search engines prior to release of v1.0.0.

BACK_TO_TOP