* In chapter 6 of THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES, Darwin focused on possible challenges to this theory, in particular the problems with identifying all the transitional forms that his theory suggested existed between species, and the evolution of elaborate organs like the eye. Chapter 7 focused on the challenges that complicated instincts presented to his ideas. Chapter 8 concerned issues that hybrid organisms presented, while chapter 9 was an apology for the weakness of the geological record as it was known as the time.

* Darwin returns to good form in chapter 6, focusing on problems with his notions, saying that though there were challenges, none were fatal:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

Long before having arrived at this part of my work, a crowd of difficulties will have occurred to the reader. Some of them are so grave that to this day I can never reflect on them without being staggered; but, to the best of my judgment, the greater number are only apparent, and those that are real are not, I think, fatal to my theory.

These difficulties and objections may be classed under the following heads:

END_QUOTE

Darwin clarified on the second concern by asking:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

Can we believe that natural selection could produce, on the one hand, organs of trifling importance, such as the tail of a giraffe, which serves as a fly-flapper, and, on the other hand, organs of such wonderful structure, as the eye, of which we hardly as yet fully understand the inimitable perfection?

END_QUOTE

The list also included the problem of the evolution of instincts, as well as the problem (as he saw it) of hybridism, but Darwin put those concerns off to the following chapters.

Darwin's concern here about transitional forms was not really about the existence or not of "intermediate forms" in the fossil record -- he took that issue on in a later chapter. He had something subtler in mind: if, say, all the different species of monkeys evolved from a common ancestral species, why do we see relatively distinct species of monkeys? Why not a continuous spectrum of different "flavors" of monkeys? Why do we have recognizable monkey species like howler monkeys, marmosets, baboons, langur monkeys? What Darwin was basically asking was: why species? Or stated somewhat differently: what are species? This is a surprisingly devious question that has been the focus of much debate since his time, and the debate continues.

One, by no means unarguable, definition of a species is of a population of interbreeding, or at least potentially interbreeding, organisms. Notice the word "population", with this population demonstrating a wide range of variation in itself. A species is not like a production model of a particular machine, with all units produced being effectively identical. Humans do not have any such uniformity; they vary over a wide range of height, weight, skin color, hair color, but despite that they still feature a large degree of commonality of form that would make them identifiable as a distinct species to any aliens who decided to pay our planet a visit.

Since humans are a single species, any sexually functional male human can in principle reproduce with any sexually functional female human. Sexual exchanges of genes within the human population establish the shared "gene pool" that is responsible for the range of traits of humans. The variation in traits among our species could be represented by the "bell-shaped curve" often used in statistical analysis -- at least in an abstract way, since the number of different features is considerable and their variation doesn't necessarily follow a nice smooth curve. Such an abstract curve would have a median (central) value of the "average" human, being of average height, weight, and so on.

Similarly, a population of a particular species of antelopes, say the elegant little gerenuks, consists of individuals who can successfully reproduce among each other and who share a range of traits, with a gene pool corresponding to those traits. That gene pool is not static -- it will change over generations from variations in individual antelopes that are added to the gene pool, while selection gradually winnows out individuals at the left ("less fit") end of the abstract bell curve, shifting the curve to the right ("more fit") end. For example, gerenuks are small compared to other antelopes, the odds are good that members of their ancestral population were bigger, but over time slowly shifted for whatever selective reason to a smaller average size.

Suppose this population of antelopes is split, say by the shift in course of a river that is too big for the antelopes to get across. Now there are two populations of antelopes that cannot crossbreed, or in other words they are "reproductively isolated". Initially both have more or less the same gene pool, but over time as variation and selection has its effect, the two populations are going to become ever more different through a process of "drift", each acquiring different features, for example clearly distinct coloration and differences in behavior.

The interesting thing is what happens if the river shifts back and the two populations come in contact again. If their reproductive isolation was only for a relatively short time, nothing too exciting happens, they start sharing genes again and create a gene pool merged from both populations. The end result is a population of hybrids -- which, incidentally, may be distinctly different in features from either of the two populations it was derived from.

However, if the isolation lasted for a long time, the two populations may have become too genetically different to breed together well or at all: They have become two species. Even if they did remain genetically compatible after their isolation, they may have acquired features -- such as males with sex colorations that excite females of one population but turn off females of the other -- that keep the two populations from sharing genes, and so they will continue to drift until they can't interbreed under any circumstances.

An interbreeding population tends to maintain a common gene pool, while reproductive isolation tends to force split populations down different paths that gradually set up barriers to reconsolidation of the gene pool. This is why there are distinct species and not a continuous range of descendants from a common ancestor. As Darwin put it, "if my theory be true, numberless intermediate varieties [...] must assuredly have existed", but they were transitions in the forms of individual populations, shifting from generation to generation.

Certainly, given a single ancestral population, over time many isolated populations of closely related descendants may emerge, giving rise to a cluster of species; however, thanks to the extinction of a good proportion of these isolated populations, the separate species in that group may be distinctly or even extremely different. The idea that there should necessarily be a continuous spectrum of species with only slight differences from one species to another is simply not how the world works; instead of emerging as a continuous smearing-together, the diversity of organisms splits into separate populations. In fact, in a few cases, if the group is in decline due to extinctions, there may be only one representative species left.

* Incidentally, in modern times we have learned that many microorganisms can perform various forms of "gene transfers" between each other, even if they are not closely related. This makes the definition of the term "species" for such organisms troublesome. Instead of a tree of life, the relationships among such organisms resemble a wild tangle of interlinked roots. Darwin said little or nothing about microorganisms in THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES, and even if he had, the discovery of gene transfers was a century beyond him.

It's probably fortunate that Darwin had no notion of gene transfers, since it would have bewildered him to no end; it's still bewildering now. This is not to say that microorganisms don't evolve -- even most modern critics of Darwin admit they do, with disease-causing microorganisms acquiring resistance to antibiotics -- it's just that the details aren't quite the same as they are for large organisms.

* Darwin did add to his discussion of intermediate forms that he could identify a few, if only a few, examples where there was a spectrum of intermediate forms:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

Look at the family of squirrels; here we have the finest gradation from animals with their tails only slightly flattened, and from others [...] with the posterior part of their bodies rather wide and with the skin on their flanks rather full, to the so-called flying squirrels; and flying squirrels have their limbs and even the base of the tail united by a broad expanse of skin, which serves as a parachute and allows them to glide through the air to an astonishing distance from tree to tree.

END_QUOTE

He immediately added that these different types of squirrels were not "perfect forms", and in fact they were in the longer scheme of things likely intermediate forms themselves:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

[It] does not follow [...] that the structure of each squirrel is the best that it is possible to conceive under all natural conditions. Let the climate and vegetation change, let other competing rodents or new beasts of prey immigrate, or old ones become modified, and all analogy would lead us to believe that some at least of the squirrels would decrease in numbers or become exterminated, unless they also became modified and improved in structure in a corresponding manner. Therefore, I can see no difficulty, more especially under changing conditions of life, in the continued preservation of individuals with fuller and fuller flank-membranes, each modification being useful, each being propagated, until by the accumulated effects of this process of natural selection, a perfect so-called flying squirrel was produced.

END_QUOTE

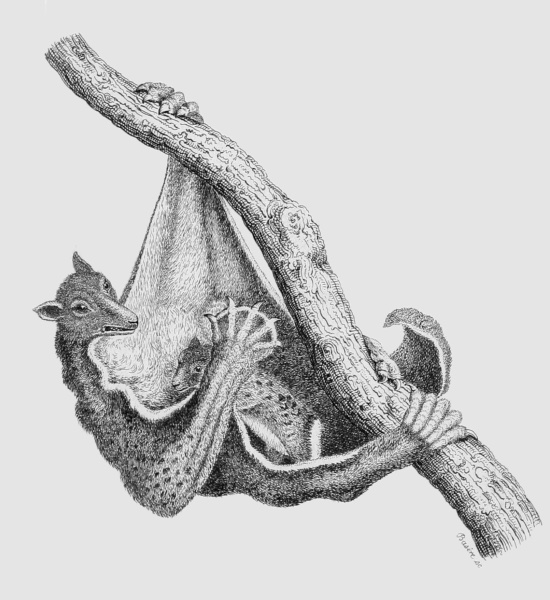

Darwin acknowledged that it was more difficult to find examples of intermediate forms between flying bats and ground-living insectivorous ancestors, but he pointed out that the gliding colugo or "flying lemur" of Southeast Asia could be seen as a creature very much along the same lines as the intermediate forms that led to the bats.

BEGIN_QUOTE:

Now look at the Galeopithecus [colugo] or flying lemur, which formerly was falsely ranked amongst bats. It has an extremely wide flank-membrane, stretching from the corners of the jaw to the tail, and including the limbs and the elongated fingers: the flank membrane is, also, furnished with an extensor muscle. Although no graduated links of structure, fitted for gliding through the air, now connect the Galeopithecus with the other Lemuridae, yet I can see no difficulty in supposing that such links formerly existed, and that each had been formed by the same steps as in the case of the less perfectly gliding squirrels; and that each grade of structure had been useful to its possessor.

Nor can I see any insuperable difficulty in further believing it possible that the membrane-connected fingers and fore-arm of the Galeopithecus might be greatly lengthened by natural selection; and this, as far as the organs of flight are concerned, would convert it into a bat. In bats which have the wing-membrane extended from the top of the shoulder to the tail, including the hind-legs, we perhaps see traces of an apparatus originally constructed for gliding through the air rather than for flight.

END_QUOTE

In reality, there has been a debate that remains ongoing from Darwin's time as to whether gliding animals actually led to flapping-wing animals. However, as Darwin pointed out, there was nothing really unreasonable about the idea. He had speculations along the same lines about the origins of whales:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

In North America the black bear was seen by Hearne swimming for hours with widely open mouth, thus catching, like a whale, insects in the water. Even in so extreme a case as this, if the supply of insects were constant, and if better adapted competitors did not already exist in the country, I can see no difficulty in a race of bears being rendered, by natural selection, more and more aquatic in their structure and habits, with larger and larger mouths, till a creature was produced as monstrous as a whale.

END_QUOTE

We know now from extensive fossils discovered later that this was not how whales actually arose -- incidentally, the closest modern ground-living relative to whales is the hippopotamus. Darwin was mocked for this comment about the swimming bear and backtracked on it later, but he was simply speculating about possibilities, and his vision was no more implausible than the one which we know from modern research to be true. Indeed, bears and seals share common ancestry, meaning ocean-going seals descended from land-living "proto-bears".

Darwin was, however, very much on the mark when he pointed out that the evidence was clear that evolution by natural selection was opportunistic, an improviser, not a designer of perfect forms:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

He who believes that each being has been created as we now see it, must occasionally have felt surprise when he has met with an animal having habits and structure not at all in agreement. [...] He who believes in the struggle for existence and in the principle of natural selection, will acknowledge that every organic being is constantly endeavouring to increase in numbers; and that if any one being vary ever so little, either in habits or structure, and thus gain an advantage over some other inhabitant of the country, it will seize on the place of that inhabitant, however different it may be from its own place. Hence it will cause him no surprise that there should be geese and frigate-birds with webbed feet, either living on the dry land or most rarely alighting on the water; [...] that there should be woodpeckers where not a tree grows; that there should be diving thrushes, and petrels with the habits of auks.

END_QUOTE

* From this comment, Darwin moves directly on to one of the best-known remarks in THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

To suppose that the [mammalian] eye, with all its inimitable contrivances for adjusting the focus to different distances, for admitting different amounts of light, and for the correction of spherical and chromatic aberration, could have been formed by natural selection, seems, I freely confess, absurd in the highest possible degree.

END_QUOTE

Darwin's critics like to cite this to show that Darwin knew perfectly well he was proposing ideas that any sensible person would see as ridiculous. However, all Darwin was saying was that intuition was misleading. After all, intuition says that the Sun goes around the Earth, rising in the morning and crossing the sky, while to us the Earth seems perfectly motionless. It took a bit of effort to finally discover that the Earth went around the Sun, and Darwin pointed out that it didn't take much effort to realize that the evolution of the eye was hardly preposterous:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

Yet reason tells me, that if numerous gradations from a perfect and complex eye to one very imperfect and simple, each grade being useful to its possessor, can be shown to exist; if further, the eye does vary ever so slightly, and the variations be inherited, which is certainly the case; and if any variation or modification in the organ be ever useful to an animal under changing conditions of life, then the difficulty of believing that a perfect and complex eye could be formed by natural selection, though insuperable by our imagination, can hardly be considered real.

END_QUOTE

In support of this assertion, Darwin pointed to the range of different eye architectures in nature. In modern times, biologists can easily point to a spectrum of eye forms, from simple one-celled eye spots in microorganisms; to a cup-like eye that provides limited directionality; to a pinhole camera eye as in the squidlike chambered nautilus; and to camera-like eyes like our own.

Critics like to mock Darwin by saying: "What good is half an eye?" The answer is: "It's 1% better than 49% of an eye." There is a clear gradation of different eye forms found in nature today, starting out from eyespots that can barely be considered 1% of an eye. Simple theoretical models have been constructed to show that a camera-like eye might well evolve from an eyespot in a few hundred thousand generations, which would be an instant on the geological timescale.

To those who claimed the eye was too complicated to have arisen by natural selection and so had to have been specially created, Darwin shot back: "Have we any right to assume that the Creator works by intellectual powers like those of man?" Humans do design complicated objects; but that says nothing to rule out that natural processes could produce complicated organisms and their biostructures, by trial-&-error over vast periods of time:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

In living bodies, variation will cause the slight alterations, generation will multiply them almost infinitely, and natural selection will pick out with unerring skill each improvement. Let this process go on for millions on millions of years; and during each year on millions of individuals of many kinds; and may we not believe that a living optical instrument might thus be formed as superior to one of glass, as the works of the Creator are to those of man?

END_QUOTE

Darwin emphatically concluded that complex organs like the eye were no "show stopper" to his theory:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed, which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down. But I can find out no such case.

END_QUOTE

Nobody has been able to find any such case since then, either. Critics keep trying to find one, but in every instance it has proven possible to at least imagine an evolutionary pathway, and very often to provide evidence to support it. In fact, the question that has to be posed in return to the critics is how they could possibly prove that no evolutionary pathway is possible.

* Darwin followed the discussion of the evolution of complex organs with musings on "organs of trifling importance". It seems a little ironic that after coming to grips with the challenge that complex organs posed to his theory, Darwin then had to address challenges posed by seemingly trivial and irrelevant biostructures to his theory -- but he was just trying to cover all the bases, demonstrating the thoroughness acquired in two decades of research.

In fact, he raised a number of very interesting points. Why would evolution by natural selection produce fripperies? The simple answers were fairly obvious. First, maybe they weren't actually as trivial as they seemed:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

The tail of the giraffe looks like an artificially constructed fly-flapper; and it seems at first incredible that this could have been adapted for its present purpose by successive slight modifications, each better and better, for so trifling an object as driving away flies; yet we should pause before being too positive even in this case, for we know that the distribution and existence of cattle and other animals in South America absolutely depends on their power of resisting the attacks of insects: so that individuals which could by any means defend themselves from these small enemies, would be able to range into new pastures and thus gain a great advantage.

It is not that the larger quadrupeds are actually destroyed (except in some rare cases) by the flies, but they are incessantly harassed and their strength reduced, so that they are more subject to disease, or not so well enabled in a coming dearth to search for food, or to escape from beasts of prey.

END_QUOTE

Maybe the "trifling" elements were remnants of biostructures that were very important at some time in the past, but due to changes in lifestyle they were being used for some lesser purpose in the present. Maybe they were sexually selected -- as noted, sexually selected features tend to seem whimsical. In addition, as he had noted earlier, modifications to organisms that did them neither harm nor good were compatible with his theory, though he did not emphasize that here.

Darwin certainly did emphasize that no organism was likely to have any feature that did it real harm -- or to the extent that it did, the harm was the price of a greater benefit: "Natural selection will never produce in a being anything injurious to itself, for natural selection acts solely by and for the good of each." Any feature that honestly did an organism harm would be subject to negative selection pressures and would disappear in time. He also emphasized that natural selection did not necessarily produce perfection in its results -- the game was not so much "survival of the fittest" as "survival of the fit enough":

BEGIN_QUOTE:

Natural selection tends only to make each organic being as perfect as, or slightly more perfect than, the other inhabitants of the same country with which it has to struggle for existence. And we see that this is the degree of perfection attained under nature. The endemic productions of New Zealand, for instance, are perfect one compared with another; but they are now rapidly yielding before the advancing legions of plants and animals introduced from Europe.

Natural selection will not produce absolute perfection, nor do we always meet, as far as we can judge, with this high standard under nature. The correction for the aberration of light is said, on high authority, not to be perfect even in that most perfect organ, the eye. If our reason leads us to admire with enthusiasm a multitude of inimitable contrivances in nature, this same reason tells us, though we may easily err on both sides, that some other contrivances are less perfect. Can we consider the sting of the wasp or of the bee as perfect, which, when used against many attacking animals, cannot be withdrawn, owing to the backward serratures, and so inevitably causes the death of the insect by tearing out its viscera?

END_QUOTE

Although Darwin had noted just previously that no organism would have any feature "injurious to itself", he immediately went on to show an example of where it certainly seemed to, with bees and wasps killing themselves when they stung an enemy. In passing, he pointed out that this wasn't any fatal flaw to his ideas -- the death of the bee contributed to the survival of the hive and the bloodline of the hive queen:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

[I]f on the whole the power of stinging be useful to the community, it will fulfil all the requirements of natural selection, though it may cause the death of some few members.

END_QUOTE

In modern times, this notion is referred as "kin selection". It's a tricky concept, trickier than Darwin understood, but he was on the right track. He certainly did grasp the fact that in a more perfect world a bee would be better off to have a stinger that could be used more than once without fatal results to its user, but evolution by natural selection simply didn't work in such a mindful fashion. Darwin went on to point out that a focus on the seeming perfection of the adaptations of organisms was a selective view of a less perfect reality:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

If we admire the truly wonderful power of scent by which the males of many insects find their females, can we admire the production for this single purpose of thousands of drones, which are utterly useless to the community for any other end, and which are ultimately slaughtered by their industrious and sterile sisters? [...] If we admire the several ingenious contrivances, by which the flowers of the orchids and of many other plants are fertilised through insect agency, can we consider as equally perfect the elaboration by our fir-trees of dense clouds of pollen, in order that a few granules may be wafted by a chance breeze on to the ovules?

END_QUOTE

BACK_TO_TOP* Chapter 7 is a continuation of chapter 6, focusing on the challenge of instincts to Darwin's concepts. He was careful not to claim he was trying to explain the origin of the human mind: "I have nothing to do with the origin of the primary mental powers, any more than I have with that of life itself." The second half of that sentence, incidentally, is significant: Darwin never tried to explain the origins of life, regarding it as a hopeless exercise given the state of knowledge of his era.

Darwin also did not strictly define instinct, but it was clear what he was referring to. Insects and spiders may have elaborate patterns of behavior, but they cannot change those patterns of behavior through experience. They can learn to the extent of finding and remembering new sources of food and the like, but otherwise their repertoire of behaviors is fixed at birth. They do not have to be taught those behaviors, and in fact they cannot be taught such behaviors. A spiderweb can be a surprisingly complicated and well-ordered structure, but the spider was born to build it, and builds it with the predictable and inflexible methodicalness of a clockwork robot.

As an illustration, Darwin pointed to the similarity between human habits and instincts:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

As in repeating a well-known song, so in instincts, one action follows another by a sort of rhythm; if a person be interrupted in a song, or in repeating anything by rote, he is generally forced to go back to recover the habitual train of thought: so P. Huber found it was with a caterpillar, which makes a very complicated hammock; for if he took a caterpillar which had completed its hammock up to, say, the sixth stage of construction, and put it into a hammock completed up only to the third stage, the caterpillar simply re-performed the fourth, fifth, and sixth stages of construction.

If, however, a caterpillar were taken out of a hammock made up, for instance, to the third stage, and were put into one finished up to the sixth stage, so that much of its work was already done for it, far from feeling the benefit of this, it was much embarrassed, and, in order to complete its hammock, seemed forced to start from the third stage, where it had left off, and thus tried to complete the already finished work. If we suppose any habitual action to become inherited -- and I think it can be shown that this does sometimes happen -- then the resemblance between what originally was a habit and an instinct becomes so close as not to be distinguished.

END_QUOTE

Darwin here seemed to be hinting at the Lamarckian transmission of acquired habits to the next generation. We know now that isn't true -- parents may educate their offspring in acquired habits, but the offspring will not be born with those habits. Certainly caterpillars are born to spin their hammocks; it isn't something they are taught by their moth or butterfly parents.

To Darwin, instincts were part of the structure of an animal; he noted that under domestication instincts might be lost -- chickens generally had little fear of dogs, despite the fact that their wild ancestors would have been mortally afraid of canines -- or gained -- dogs, with their pack instincts adjusted to make them almost inherently loyal to humans. Dogs in fact displayed a wide range of instinctive actions, for example the urge of sheepdogs to circle sheep and chase them back into the flock.

If indeed Darwin was leaning towards Lamarckism in his discussion of instinct, it did not affect his basic argument: that instinctive patterns of behavior were perfectly consistent with evolution by natural selection, the evolution of instincts was no more unreasonable than the evolution of the eye. He believed that, as with the different forms of the eye, gradations of increasingly sophisticated behaviors could be found in nature to back up his concepts:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

No complex instinct can possibly be produced through natural selection, except by the slow and gradual accumulation of numerous, slight, yet profitable, variations. Hence, as in the case of corporeal structures, we ought to find in nature, not the actual transitional gradations by which each complex instinct has been acquired -- for these could be found only in the lineal ancestors of each species -- but we ought to find in the collateral lines of descent some evidence of such gradations; or we ought at least to be able to show that gradations of some kind are possible; and this we certainly can do.

I have been surprised to find, making allowance for the instincts of animals having been but little observed except in Europe and North America, and for no instinct being known amongst extinct species, how very generally gradations, leading to the most complex instincts, can be discovered.

END_QUOTE

Spiderwebs demonstrate this principle of gradualism -- some are very simple, strands strung around haphazardly, not like the elaborate webs of orb spiders. There is also a broad range of diversity in spiderweb forms.

Darwin considered a number of interesting instinctive behaviors: the habits of many species of cuckoos to lay their eggs in the nests of other birds, the species of ants that enslaved other ants, and the construction of hives by bees. Darwin pointed out that while the hexagonal cells of a honeycomb are almost geometrically perfect for their purpose, there are species of bees that don't do anywhere as neat a job, suggesting the evolutionary emergence of the instincts to create such elegant structures.

* In chapter 8 of THE ORIGIN OF THE SPECIES, Darwin returns again to the theme of hybridism, and again it is somewhat hard to comprehend now as to why he discussed it at such length. Distantly related species could not crossbreed; more closely related species could, though their offspring were often sterile. That is exactly what would be expected with two populations of organisms evolving from a single common ancestor population -- a gradual divergence between the two populations until their genomes began to mismatch, at first to the extent of producing sterile offspring, and ultimately to mismatch to the extent that the two populations could not crossbreed at all.

It is also not surprising that hybrid offspring of these two separated populations could sometimes be enhancements in various ways on the members of each individual population, a notion referred to as "hybrid vigour". In sexual reproduction, there was no reason that the shufflings of the "decks" provided by the two different parent stocks could not give offspring "decks" of their own that incorporated the best of the two. On the other hand, it could give the offspring the worst of the two; in that case, the offspring would then tend to die out.

Darwin seems to have understood all of this, but he was fascinated by the details of the process and elaborated on them at length in this chapter -- while, frustratingly, admitting that he couldn't make complete sense of the issue. The ordinary reader of the 21st century doesn't find it so fascinating.

BACK_TO_TOP* In chapter 9 of THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES, Darwin focused on the problem of obtaining support for his theory from the geological record. If there were in fact innumerable transitional forms between modern species, then it might seem that there would be a record of them in the stones:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

Why then is not every geological formation and every stratum full of such intermediate links? Geology assuredly does not reveal any such finely graduated organic chain; and this, perhaps, is the most obvious and gravest objection which can be urged against my theory.

END_QUOTE

To which he answered:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

The explanation lies, as I believe, in the extreme imperfection of the geological record.

END_QUOTE

Fossilization is basically rare -- most organisms that die decay completely and leave no long-term trace, with soft-bodied organisms much less inclined to fossilization than organisms with bones or shells. Fossilization tends to take place if organisms are sealed in sediments or under volcanic ash, where the processes of decay are minimized and the bodies of the creatures end up turning into stone. Add to this the problem that the Earth's geological processes tend to grind up stone and recycle it, destroying traces of the past.

It was not surprising, then, that Darwin complained about the "poorness of our paleontological collections". Paleontology had effectively not existed before the 19th century, and though there had been considerable public excitement over the fossils found to Darwin's time, the field was still young. It had yet to build up a large body of evidence and knowledge.

Darwin had good reason to apologize for the poverty of the fossil record in 1859; but though critics still try to claim the fossil record as a weakness of Darwin's ideas, in the 21st century no paleontologist sees the need to apologize any more. In a century and a half of work, the number and quality of fossils has exploded. Even in Darwin's lifetime there were major discoveries, such as those establishing the origins of birds and horses, and since then matters have only improved -- the occasional false step or hoax doing little to undermine the credibility of the far greater body of evidence.

In modern times, paleontologists have been able to trace in considerable detail the fossil record of the transition from fish to amphibian, from reptilian creature to mammal, from land-living mammal to whale. Some paleontologists still describe the fossil record as "sketchy" -- but if so, it's vastly less sketchy than it was in 1859. In fact, given the rate of discoveries in recent years, the critics of Darwin are becoming more muted in their sniping at the fossil record as supposed "gaps" are continually plugged by impressive new fossil finds.

* Darwin also almost effusively apologizes for the for what he called a "grave" difficulty with his theory: "I allude to the manner in which numbers of species of the same group, suddenly appear in the lowest known fossiliferous [fossil-bearing] rocks." The fossil record, at least in Darwin's time, appeared to abruptly start in what is known as the "Cambrian" period, with no gradual ramp-up before that time in the number and elaboration of species.

The critics are also fond of playing up the "Cambrian explosion", but it remains hotly argued among paleontologists as to whether any such thing even happened:

Darwin similarly fussed over the emergence of entire groups of organisms in later periods, but he was foresighted in suggesting there was more than met the eye in such emergences: further investigations by paleontologists have tended to show that "sudden appearances" are an artifact of the geological record -- such groups did not arise quite as rapidly as they seemed to, and that the emergence of these groups actually took place over a considerable period of time. In general terms, Darwin understood that the geological record did not so much challenge his theory as lend it sketchy support, showing an evolutionary emergence of different organisms over time, featuring a succession of forms:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

For my part [...] I look at the natural geological record, as a history of the world imperfectly kept, and written in a changing dialect; of this history we possess the last volume alone, relating only to two or three countries. Of this volume, only here and there a short chapter has been preserved; and of each page, only here and there a few lines. Each word of the slowly-changing language, in which the history is supposed to be written, being more or less different in the interrupted succession of chapters, may represent the apparently abruptly changed forms of life, entombed in our consecutive, but widely separated formations. On this view, the difficulties above discussed are greatly diminished, or even disappear.

END_QUOTE

Sketchy support, Darwin points out, is better than no support -- and no support is exactly what the fossil record supplies to any alternate theory of the origin of species proposed to date. As has been emphasized by Darwin's modern admirers, he made a good enough case for his concepts so that, in their refinement and validation over the decades, we would be perfectly justified in accepting them even if the geological record was completely mute on the issue. We know now that it is far from mute, and all we know from it supports Darwin's ideas -- giving us double the justification for accepting them.

It is a bit exasperating to see how Darwin's remarks about the limitations of the fossil record have been exploited by his critics -- but it is a simple statement of fact that Darwin was describing matters as he knew them in his time, and a testimony to his thoroughness that he zeroed in on what he knew to be weaknesses of his ideas. However, should he drop in today, he would be gratified to see that they are not really weaknesses any longer, and would spend a great deal of time in extreme pleasure examining modern natural history museums.

BACK_TO_TOP