* Even those who accept MET may have confused ideas about it, most notably a concept of "progress". If such a notion can be applied to MET, it is only in a very loose fashion. However, at the same time, it cannot be said that MET is disorderly, since it exhibits a very clear, if elaborate, sort of order -- if not one that dovetails neatly with human concepts of order.

* To tie up the discussion of MET, it's worthwhile to give a close look at its most startling feature -- its lack of preplanned goals, its lack of specification. The only sense in which it has a direction is in a drive towards increased fitness, which can take place by any available route. How could such a blind process have produced such complex organisms?

The fundamental answer is that natural selection does not produce a solution; it provides any solution that works in some way, any way. In fact, its lack of specification can be seen as an advantage. Suppose we compare MET to the method of an inventor, Alice, who keeps coming up with minor variations on her existing inventions at whim, implementing them without much thought for whether they have any merit or not. She then plays with them extensively to see if they do anything, absolutely anything, better than something she's already got; it doesn't even have to be related to what the inventions originally did. If they are an improvement, she adds them to her stockpile of inventions as a basis for further tinkering.

If Alice were trying to build something to meet a specific customer requirement using this method, the odds of her meeting that customer spec with this method are vanishingly small. However, she doesn't care what he comes up with, as long as it marginally works better than something she already has in her stockpile in some way, and the odds of achieving this are far better. Alice, in short, is using evolutionary design, instead of "Intelligent Design", and finds that evolutionary design is perfectly workable. After all, it's perfectly workable for evolutionary design software, too.

Evolutionary design does require a bit of "intelligence", just enough to follow the rules. Genetic variation produces minor variations in organisms, with the Grim Reaper sorting out which ones do anything, absolutely anything better, and consigning the ones that do things worse to extinction. As Darwin himself pointed out, evolution's design process is tireless, and doesn't miss anything important. MET is workable not in spite of its simplicity, but because of it.

In fact, it can be argued that MET doesn't so much rule out complexity as assures it. Alice's evolutionary design is "serendipitous", able to come up with a wild range of inventions, literally not even constrained by imagination. Similarly, biological evolutionary design tends to produce a wild range of biological adaptations; if there's some open niche in an ecosystem, sooner or later natural selection's likely to come up with some organism that exploits it, just on the basis of the odds.

By the same logic, if useful adaptations are possible for a particular organism -- protective coloration, a toxin, spines, and so on -- sooner or later natural selection is likely to come up with one or more of them. It will also do so without any concern for consistency, sometimes doing things more or less the same way in different cases, sometimes doing things entirely differently, the only real constraint in any case being the inescapable constraint of building on what had come before.

The obvious objection to this scenario is: "But it would take forever to get results this way!" The reply is almost as obvious: by human standards of time, it does take forever, far longer than our lifespans, even longer than the lives of civilizations. A few million years is not a long time in terms of geological or evolutionary history; in contrast, recorded human history runs to a few million days. Evolution literally has all the time in the world.

Still, people in general have a hard time fully grasping the implications of the unspecified nature of evolution. As Richard Dawkins famously put it: "It is almost as if the human brain were specifically designed to misunderstand [evolution], and to find it hard to believe." Our language itself is arranged to describe natural structures as constructs of a sort, and read deliberative plans into chance events. Humans design and build things according to plans, and it's just too easy to fall into the parochial trap of thinking the Universe works the same way when there's actually no specific reason to believe that it does.

As far as MET is concerned, evolution doesn't have a long-range plan, doesn't have specific objectives in mind, isn't working from a blueprint. In terms of human prejudices, it seems to be missing something: Elaborate organisms can't come together by themselves, can they? It's counter-intuitive, just as was the idea that the Earth goes around the Sun and not the reverse, and requires a bit of imagination to accept.

Thomas Huxley more or less invented the classic chart of showing a progression of apes to humans, which has been updated over time to include various prehuman species and still shows up in cheesy popular science articles, as well as in parodies. Even among the general public that accepts evolution, this vague concept of progress remains a widespread implicit assumption -- but it is bogus, and bogus in a fundamental way that is not a nitpicking or ideologically-driven distinction. The idea of evolution in predefined directions is more or less Lamarckian; in evolutionary thinking, there's just adaptation to survival and propagation, and no other goal.

Going back to the evolutionary analogy with languages, is the change in English from Chaucer's time to our time really an "improvement"? Certainly modern English has terminology to describe things beyond Chaucer's imagination, it's better "adapted" to its environment, but beyond that is the language "superior"? The concept of evolutionary progress has sometimes been called the "Whig view of history": the past is a progression to our current state of perfection. The notion is arguable. We refer to creatures that have been around for a long time in much the same form as "primitive", but this is a problematic description -- true in the sense that their direct links to ancestors are older than the rest of us creatures, more "primal", but they are often neatly adapted to their environments and have proven very successful.

In evolutionary terms, the distinction of "primitive" in the popular sense of "crude" is meaningless. Prokaryotes have been around for far longer than multicellular organisms, their adaptations can be startlingly elaborate, and they are beyond all doubt successful in evolutionary terms. It is worth remembering that our perception of the biosphere as dominated by familiar plants and animals is something of an illusion, since the bulk of the biomass of our planet still consists of prokaryotes.

In fact, evolution can often result in what would be seen from the Whig point of view as backward steps: barnacles have lost the free-living life of a shrimp and acquired a sedentary life like that of a clam, in fact some of them have become parasites that are hard to distinguish from a fungal infection; fish that live in caves usually end up losing their eyes since they're so much vulnerable excess baggage in such a blackout environment. Such creatures are sometimes said to have "devolved" or evolutionarily "regressed", but have they? These creatures are well adapted to their environments, and that's all that matters in evolution.

Many biologists emphatically reject any notion of progress in evolution, seeing it as little more than imposing human value judgements on a process that is indifferent to them. Dawkins has suggested that if swifts, those marvelous aerobatic masters of the air -- anyone who's ever lived around them can only admire their dazzling formation aerobatics -- were able to write books, they would probably come up with a similar progress from sparrows to swallows to their own state of perfection. We score high on the intelligence scale; swifts score high on the aerobatic scale.

BACK_TO_TOP* Some biologists have suggested that the single-minded focus on the undirected nature of evolution may be correct in the strict sense, but it is strict to the point of blinkered and blindered. A subjective judgement or not, not everybody feels comfortable saying that humans aren't generally a refinement of some sort on bacteria.

The history of life on Earth does demonstrate a certain overall trend towards greater elaboration of organisms and ecosystems: evolution certainly seems to tend toward increasing biological diversity. Suppose the Earth started out with a simple ecosystem consisting of a few strains of bacteria. If these bacteria were mutable, as they were, they would in time lead to an increase in the numbers of strains of bacteria. Given random mutations, the bacteria would into new forms, some of which could fit into ecological niches that were not previously exploited, though most of the mutants would simply die out. A mutable simple system that builds on its changes is going to become more diverse, once again on the basis of the odds.

The simple bacteria would, by the same logic, lead to more elaborate single-celled organisms, in turn leading to multicellular organisms and all the plants and animals (like ourselves) that we are familiar with. If we observe the emergence of a branching tree, occasional prunings aside, it becomes more elaborate as the branches proliferate.

To be sure, there's nothing in evolution to prevent what humans might judge as evolutionary "regression", and certainly mass extinctions will partially reset the process every now and then, but the system is also likely over the long run to come up with evolutionary acquisitions such as feathers, milk, toxins, bigger brains, whatever. If life has arisen on other planets in the Universe, doesn't it seem plausible -- of course not provable, but certainly plausible -- that eventually it would ratchet itself up to consciousness and intelligence? If that doesn't define "progress", then what does?

There is also the fact that biological configurations re-occur over and over again, through convergent evolution: sharklike forms, flapping-wing forms, glider forms, mole forms, camera eyes, and so on. Of course they arise again and again, because of all the possible solutions, they're on the list of ones that work. There's a well-known and much-admired book, ON GROWTH AND FORM, published by D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson in 1917, that commented on the emergence of such regular patterns in biological systems at a lower level. Thompson most famously showed how the Fibonacci sequence, in which each number in the sequence is the sum of the previous two:

1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34 55 89 ...

-- occurs or is implied in many different contexts in biological systems, from the growth of spiral shells to pine cones to the heads of sunflowers and so on. It's no surprise it does: if the growth of a biological structure like a spiral shell at one stage is proportional to the size attained from previous stages, then the growth will follow an exponential curve and track the Fibonacci sequence. The emergence of the Fibonacci pattern is not magical; it is simply dictated by the way things work, need to work, in the real world.

Although Thompson accepted evolution, he rejected natural selection as a significant mechanism, claiming out that such structural constraints were the driving force. While Thompson made an eloquent and brilliant case for his "structuralist" ideas, the general belief nowdays is that his notions were not at all incompatible with MET: natural selection works, but it is certainly subject to constraints that channel it into certain directions.

Richard Dawkins gave an admiring nod to Thompson's ideas, describing at length in his book CLIMBING MOUNT IMPROBABLE a computer simulation that explored the emergence of form in spiral shells, and the wild variations in form that shells could take given changes in a small set of parameters. Modern advocates of the application of concepts such as "emergent systems" to evolutionary science have claimed their notions involve "revolutionary" changes to MET, but at least in a broad sense their ideas are following in the trail of Thompson's: evolution reflects underlying physics, underlying structure.

* In other words, if evolution isn't specifically directed, that does not mean it has no directions. It unarguably does: it tends toward diversification and the filter of natural selection is biased towards patterns that work, with those workable patterns constrained by laws of logic and physics. We tend to see similar evolutionary designs over and over.

Still, humans evolved bigger brains, but only because circumstances set up selection pressures toward that end. Maybe it was something likely to happen over the long run, but as far as MET is concerned, there was never a "planned improvement program" as would be drawn up for a combat aircraft to move from the "Mark I" version to the "Mark X" version.

The core notion of evolution is that life has a history; the organisms that we know of today did not always exist, they emerged along many paths from common roots over deep time. As with human history, knowing what happened in the past gives us little ability to say where things go from here. What will evolve next? We can't say, other than that the organisms of the future will be the descendants of the organisms of today, and they will be more fit to their particular environment.

BACK_TO_TOP* If we can't predict what species will emerge in the future, we can still have fun envisioning possibilities. A Scots geologist named Dougal Dixon (born 1947) wrote a series of speculative books that imagine "bestiaries" of Earths of the future, or Earths where the dinosaurs didn't die out. Dixon's speculative books are "science fiction" in the strict sense of the term, exercises in imagination grounded in the sciences, and though they're basically intelligent amusements they are also thought-provoking, showing how evolutionary principles could give rise to new organisms in different scenarios. They might be considered as "thought experiments".

In his classic 1981 book AFTER MAN, he offers the premise that humanity and quite a few species of animals died out in an unspecified catastrophe, with a new world order emerging over tens of millions of years. Rats form the basis of major predator groups, evolving into wolflike or even bearlike forms, while rabbits evolve into "rabbucks", creatures like long-eared llamas -- one branch of which runs like antelopes, the other which hops like kangaroos.

Consider the possible adaptations of rats in a world where most other mammals have died out. How much change would a rat undergo to resemble, say, a weasel? It would end up with sharper claws, modified teeth, a longer and more flexible body -- all of which could result from a fairly small number of genetic mutations, mostly tweaks of existing developmental genes, no more generally implausible, arguably even less implausible, than the transformation of a wolf into a pekinese. The same exercise can be applied to the changes a rat would undergo to result in something like a cat: a bigger body, longer legs, keener eyes and ears, more formidable claws and teeth, different coloration -- once again a fairly modest set of genetic changes. The "tree" of rat-derived predators could then diversify into larger and more formidable beasts -- a rat-cat could easily be the ancestor of a rat-panther through a direct scaling-up, and the rat-panther an ancestor of a rat-sabretooth.

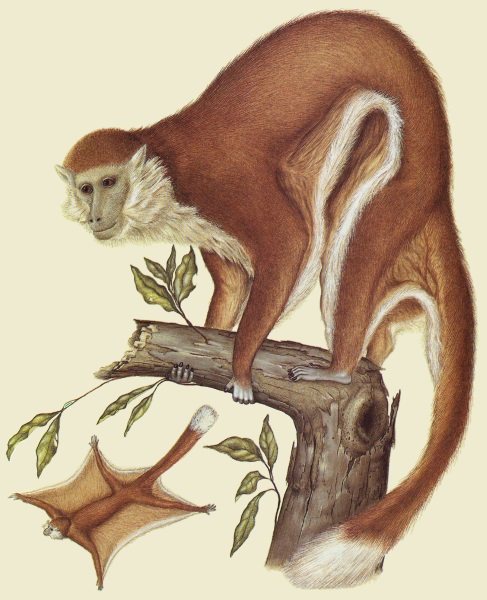

Many of the other beasts of Dixon's future Earth are similarly straightforward derivatives of creatures of our own time, for example "flying monkeys" or "flunkeys", which are Old World monkeys with flaps of skin from the front to back legs to allow them to glide from tree to tree, like flying squirrels. That's a very plausible adaptation, since the "glider" format has been "reinvented" so many times. There are also "swimming monkeys" that live in trees along bodies of water, diving in to swim with webbed feet and snatch fish with clawed hands. The eyes, ears, and nose are placed high on the head to keep them above the waterline, just as they are in hippos.

Whales died out in the mass extinction, with the descendants of penguins moving into the ecological vacuum -- resulting in the dolphinlike "porpin" as well as the "vortex", a penguin the size of a humpback whale, with a beak adapted to act as a krill strainer. Again, the genetic changes involved in the emergence of these beasts are fairly modest -- changes in scale; adjustments of organs to deal with bigger body mass; alterations in the beak, with the porpin featuring serrations on its long beak to allow it to catch fish more easily; and so on. An analysis of the genomes of these animals would reveal that they remained clearly similar to the genomes of penguins of our era.

Of course, since evolution tends to produce surprises, Dixon's animal world of the future also contains more than a few freaks -- for example, the "flooer", a bat that has lost its wings and returned to a ground-dwelling existence, acquiring a face that looks like a flower and saliva that smells like nectar to allow it to ambush pollinating moths and butterflies. Ridiculous? No more or less than a mantis that looks like an orchid -- camouflage to trap pollinating insects with, just like a flooer -- or sea dragon that looks like seaweed. The flooer also provides an example of how evolution "makes do" with what is available, resulting in bats that can't fly.

BACK_TO_TOP* I ended up writing this document because the squabbling over evolutionary science got too loud for me to tune out. I had to sit down and sort through the facts, starting out by reading Dawkins' THE BLIND WATCHMAKER. I took a set of notes out of it, which provided a basis for this document.

The initial release in 2008 was in three parts -- the first a history of evolutionary science, the second a history of life on Earth, and the third this document. In 2017, after a series of revisions, I decided it would be more convenient in all respects to split the first two parts off as separate books.

I also ended up redefining this document in light of writings of Dan Dennett, an enthusiastic advocate of the concept of "evolutionary design". Evolutionary scientists have traditionally tended to bristle at that notion. As Dawkins famously put it, bat sonar and other marvelous natural adaptations are "complicated things that give the appearance of having been Designed for a purpose", with Dawkins speaking of "the illusion of Design". Dennett responded that organisms look so clearly designed that it is perverse to argue to layfolk that they really aren't.

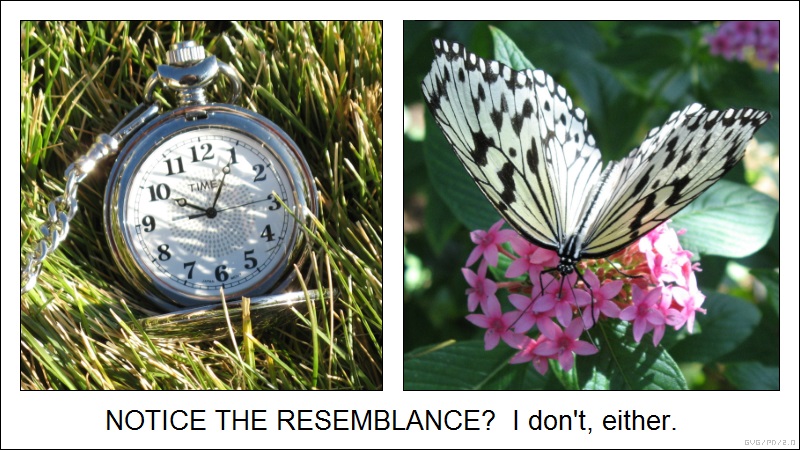

That's a tempest in a teacup. The Reverend Paley's teleology has a strong appeal to intuition, since we have an egocentric bias to believe it: we impose human ways of doing things on a Universe that, as all admit, isn't run by humans. People are inclined to see it as so obvious as to be unarguable -- oblivious to the reality that Paley's comparison of watches to organisms is silly. Anyone who has actually done earnest homework on MET knows Paley was telling a joke, but didn't realize it. The gulf between the two viewpoints cannot be bridged. Embracing the notion of evolutionary design doesn't influence the conflict one way or another.

So why bother with evolutionary design? Who needs such a contraption? Because it's no bother; it's much more a contraption to try to tapdance around the "appearance of Design". Of course organisms are designed, by evolution, to be more fit to their environment. If evolutionary software can design antennas, what reason is there to say biological evolution did not design bats, snakes, and dolphins? And they are indeed designed for a purpose -- to survive and propagate, using the tools they acquired from evolution to pursue their lifestyles. Evolutionary design is the cleaner and more convenient way of looking at things.

As far as creationism goes, I've long since taken its measure, and pay it no more mind than the occasional mockery: "So, what can you tell me about your [INVISIBLE GREMLINS DID IT WITH MAGIC!] theory? Nothing? That's what I thought." Creationism amounts to nothing, and I have to apologize to readers for even mentioning it.

However, instead of finishing on a weary note ... reflecting on the mockery that MET is like thinking that a bunch of monkeys pounding on typewriters could produce the Bible, I recall a very short fantasy story I read when I was a lad, about a scientist who trained a group of chimpanzees to type and let them go at it. They promptly produced the Bible, the complete works of Shakespeare, and were pounding out the ENCYCLOPEDIA BRITANNICA when the scientist flew off the handle and shot them all. Only one badly-wounded chimp was still moving after the massacre; with his dying breaths, he crawled up to the typewriter and punched out:

T H E E N D

* Sources include:

I spent a considerable amount of time surfing the internet for interesting background materials. The discussion of the evolution of toxins was from a blog entry by P.Z. Myers commenting on the work of Australian naturalist Brian Grieg Fry.

Of course, I have to give credit to my neighborhood prairie dogs, who are always amusing and also a good source of evolutionary inspiration. When I walk past their warrens, they bark -- it's a chirp, really -- as an alarm, and scurry to their warrens. I've taken to chirping loudly myself to warn them I'm coming. It seems to puzzle them.

* Illustrations credits:

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 jan 08 / INTRO TO EVOLUTIONARY SCIENCE, 22 chapters.

v1.1.0 / 01 apr 08 / Title INTRO TO EVOLUTION, went to 24 chapters.

v1.2.0 / 01 jun 08 / Added DR. TATIANA info, various polishings.

v1.2.1 / 01 jul 08 / Extensive small tweaks.

v1.2.2 / 01 aug 08 / A few more tweaks, went to 28 chapters.

v1.3.0 / 01 jan 09 / Deleted chapters on Darwin Wars, 21 chapters.

v2.0.0 / 01 may 09 / General rewrite, cut origin of life material.

v3.0.0 / 01 jun 10 / General rewrite, went to 24 chapters.

v3.0.1 / 01 jul 10 / Multiple cleanups on v3.0.0.

v3.0.2 / 01 sep 10 / Follow-on cleanups.

v3.1.0 / 01 jul 12 / Additional musings on Social Darwinism.

Changed references to "critics" to "creationists".

Added cartoon illustrations.

Fixed references to geologic eons.

Changed "Cambrian explosion" to "Cambrian expansion".

Updated marsupial evolution, added Janjucetus.

Simplified plant domestication, added epigenetics.

v3.1.1 / 01 oct 12 / Quick & dirty upgrade, mostly for new illustrations.

Polishing remarks on creationism, Lamarckism.

Comments on ENCODE study.

v3.1.2 / 01 nov 12 / Follow-up to add image sizes, more polishing.

v3.2.0 / 01 jul 13 / Split chapter on consciousness etc, 25 chapters.

v4.0.0 / 01 jul 15 / Reorganized, got rid of many of the comments on

creationism; cut to 22 chapters.

v5.0.0 / 01 jun 17 / Split into three documents, this one 8 chapters.

Modified, changed title to EVOLUTIONARY DESIGN.

v5.0.1 / 01 jun 19 / Review & polish.

v5.0.2 / 01 jun 21 / Review & polish.

v5.0.3 / 01 may 23 / Review & polish.

v5.0.4 / 01 may 25 / Review & polish.

BACK_TO_TOP