* Although General Grant had been stymied in his first push on Vicksburg, he wasn't inclined to give up, spending the first months of 1863 exploring a number of back-water schemes to bypass the city. None of them worked out, but he persisted. In March, Admiral Farragut took his fleet north up the Mississippi past the Confederate stronghold at Port Hudson in a noisy night-time battle. Not to be outdone, in April Grant ran his forces down the river past Vicksburg, in hopes of confounding the Confederate defense of the city.

* Ulysses Grant arrived in Memphis, Tennessee, on 10 January 1863, ahead of his columns as they withdrew north out of Mississippi after the failure of his offensive against Vicksburg. Major General James MacPherson, one of Grant's ablest and most trusted generals, stayed with the men to lead their retreat, while Grant returned to headquarters to sort out whatever confusion had accumulated there in his absence.

With communications cut by Van Dorn and Forrest, for all Grant knew Sherman might have had better luck in his move on Vicksburg. Of course, that wasn't the case. When Grant got to Memphis, he received a letter sent by McClernand from Milliken's Bend, informing him of the failure of Sherman's attack and indicating McClernand's intention to attack Fort Hindman -- up the Arkansas River, used as a base to disrupt Union shipping on the Mississippi. Grant was not pleased by this news, regarding the attack on Fort Hindman as a diversion of effort from the proper goal of moving down the Mississippi and cutting the Confederacy in half -- and even irresponsible, considering that Nathaniel Banks was supposed to be moving upstream to link up with them.

Grant said as much in a reply sent to McClernand the next day, 11 January, the same day that Fort Hindman fell to his troops. Union casualties were over a thousand; the Confederates lost five as many, mostly taken prisoner. Grant's message ordered McClernand to return to Milliken's Bend. Grant echoed the criticism in a telegram to Halleck, complaining that McClernand had gone off on a "wild-goose chase", and requested instructions. He got them, in terms that were remarkably direct for Halleck:

YOU ARE HEREBY AUTHORIZED TO RELIEVE GENERAL MCCLERNAND FROM COMMAND OF THE EXPEDITION AGAINST VICKSBURG, GIVING IT TO THE NEXT IN RANK OR TO YOURSELF.

Halleck disliked McClernand, all the professional generals did, and Grant had just given Halleck an opportunity to do something about it. However, if Grant felt he now could put McClernand firmly in his place, he was quickly forced to be cautious doing it. Within a day, news arrived that Banks hadn't made it past Port Hudson in his upriver drive; and that Fort Hindman had fallen, handing McClernand a shiny little victory that made Grant think twice about treating him roughly. Besides, Grant also found out that his friend Sherman had been behind the whole adventure, which cast a different light on the matter. Sherman had reasoned that Fort Hindman was a threat to the Federal rear, having been used as a base for attacks, and should be neutralized.

In any case, on 17 January Grant left Memphis on a steamship for Napoleon, Arkansas, just south of the outlet of the Arkansas River into the Mississippi, to meet McClernand, Sherman, and Porter, and take command in person. Grant arrived the next day. An Illinois soldier pointed him out to a colleague: "There's General Grant!" The other soldier looked over the shabby-looking Grant and shook his head: "I guess not. That fellow don't look like he has the ability to command a regiment, much less an army."

Grant was actually commanding an army, and at that moment was ensuring that he remained in command of that army. McClernand had been busy exploiting his success at Fort Hindman by sending two gunboats up the White River in Arkansas, where they sent the rebels fleeing from Saint Charles and then smashed the railroad depot at De Valls Bluff, the midway point on the rail line between Little Rock and Memphis.

McClernand had still been at Fort Hindman when he got Grant's message. He had obeyed and gone downriver to Napolean, but had also sent Grant's letter to Abraham Lincoln -- along with a note complaining about Grant's unreasonable and spiteful attitude, and lobbying for the independent command that would allow him to ignore Grant's orders. Lincoln bluntly replied that he had no interest in the dispute. Whatever fair case McClernand might make for himself, he was severely handicapped. Lincoln knew he was insubordinate, and he had made too many enemies, including Sherman, Porter, Halleck, and War Secretary Stanton; he had to live with the consequences, like them or not.

Grant, in turn, was having his own preconceptions adjusted as he talked to Sherman and Porter about the failed adventure at Chickasaw Bayou. It appeared Grant's vision of a bold drive down the Mississippi was not, for the moment, realistic. An indirect approach might actually be more workable -- though that didn't mean that he felt any more sympathetic to McClernand. Grant sent a somewhat devious message to Halleck on 20 January to obtain reassurances on his own command authority, commenting that he had been informed that the "Army and Navy" had no great confidence in McClernand. The two branches of the service in this case were represented largely by Sherman and Porter, who had expressed such opinions in response to Grant's own queries.

The next day Halleck gave Grant the reassurances he wanted, along with command of almost 100,000 men scattered about the Mississippi basin. Halleck had once tried to put Grant on a leash; now he was giving Grant everything he wanted. Grant proposed to consolidate his force and conquer Vicksburg once and for all. In the message of 20 January, Grant had also indicated that he wanted to finish the canal across the hairpin turn of the river near Vicksburg, abandoned by the Federals the summer before. On 25 January, Grant received a message from Halleck reporting the President was very enthusiastic about this idea.

Sherman was already laboring on the canal. It was wretched work, since the rains that had forced him to give up his first attempt on Vicksburg were continuing to pour down. While the summer and fall had been drought-stricken, the winter was proving to be one of the wettest anyone could remember. There was no way to stay dry, and it was everything the soldiers could do to keep from being washed away by rising waters. Sherman himself took a couple of good dunkings, once on a horse and once on foot, when he stumbled into potholes hidden under the muddy water. The air was black in places with gnats. The canal seemed like a fool's errand; even if the Federals improbably succeeded in getting the Mississippi to shift its course away from Vicksburg, the Confederates could easily move their defenses south to the canal's outlet.

Sherman was depressed at his work and the progress of the war. Porter described the general as "half sailor, half soldier, with a touch of the snapping turtle," and did what he could to bolster his colleague's morale. Porter sent Grant a message on 27 January: "If this rain lasts much longer we will not need a canal. I think the whole point will disappear, troops and all, in which case the gunboats will have the field to themselves." That day, Grant got on a steamship, and the next day joined Sherman and Porter near Vicksburg. Porter reported to Gideon Welles: "I hope for a better state of things."

BACK_TO_TOP* David Dixon Porter had enthusiastically cooperated with his friends Grant and Sherman in their various offensive schemes, but Porter was too energetic to be satisfied at merely helping the Army in their plans. He had plans of his own.

As long as the Confederacy held Vicksburg and Port Hudson, the rebels controlled roughly 300 miles (480 kilometers) of the Mississippi, allowing them to maintain commerce between East and West. Porter believed that he could break that link by running warships south down the river past Vicksburg. Once downriver, they could set up bases from which they could sever Confederate traffic on the river. It was a logical extension of the coastal blockade strategy to inland waterways.

In early February, Porter had the steam ram QUEEN OF THE WEST, now armed with a few guns to complement her ram, make the run past Vicksburg in broad daylight. While the ram took a dozen hits, none were serious, with the QUEEN OF THE WEST even taking the opportunity to ram the Confederate gunboat CITY OF VICKSBURG, while it sat at dock below the city -- with the ram's crew then setting the rebel gunboat on fire, using incendiaries made of cotton wads soaked with turpentine.

After a little resupply and refit, the QUEEN OF THE WEST then embarked on an extended and profitable raid down the Mississippi and up the Red River, destroying Confederate cargo vessels and seizing steamships. Unfortunately, while following up reports of a Confederate battery on the Red River in Louisiana on 14 February 1863, Valentine's Day, the QUEEN OF THE WEST ran aground on a mud bank. The reports of the battery turned out to be perfectly true, since rebel gunners then began to pound the immobilized steamship. The crew jumped overboard, leaving the QUEEN to the rebels, to escape on a steamer they had captured from the rebels, the NEW ERA NUMBER 5.

The rebels pursued with a fast gunboat named the WEBB. The Federals on board the NEW ERA threw everything they could over the side to stay ahead in the race, for though the WEBB only had one gun, the NEW ERA was unarmed. Two days later, on the morning of 16 February, the NEW ERA was moving upriver north of Natchez when the crew encountered a fearsome-looking vessel that, after a few anxious moments, turned out to be the Union river ironclad INDIANOLA. It was the latest and most impressive addition to the Federal gunboat fleet, with armament of two 11-inch (28-centimeter) guns mounted forward and a pair of 9-inch (22.9-centimeter) rifles mounted amidships, and four steam engines that drove sidewheels and twin screws.

Porter had sent the INDIANOLA, under the command of Lieutenant Commander George Brown, downstream past Vicksburg to reinforce the river blockade. The ironclad carried two barges full of coal, one lashed to each side, to provide fuel for operations. The INDIANOLA and the NEW ERA went downstream to encounter the WEBB moving upstream. The captain of the rebel gunboat took one look at the INDIANOLA and sensibly turned tail, with the INDIANOLA firing a few shots to hurry him on his way. The WEBB managed to make it to the mouth of the Red and escape upriver. Brown, learning of what happened to the QUEEN OF THE WEST, knew better than to follow without an experienced river pilot to keep him from running aground. He decided to stay where he was to keep the rebels bottled up, while the NEW ERA went upstream to give Porter a report.

A few days later, however, Brown found out that the Confederates had refloated the QUEEN OF THE WEST, repaired it, and were taking it downstream, along with the WEBB and two other vessels, to engage the INDIANOLA. Brown considered standing and fighting -- then decided against it, taking the INDIANOLA back upstream on 21 February. Since he hoped that the NEW ERA would send back reinforcements, he held on to the two coal barges, though they slowed the gunboat down considerably.

The INDIANOLA was about a dozen miles downriver of the nearest Union battery on 24 February, when the Confederate fleet caught up with her after sundown. The rebel commander, Major Joseph L. Brent, had held back until nightfall, calculating that in the darkness the big Union ironclad would not be able to make use of her superior firepower. The fight was confused and short. The INDIANOLA fired wildly into the night but only scored one hit, on the QUEEN OF THE WEST. The ironclad was rammed repeatedly by the QUEEN and the WEBB. The WEBB was damaged severely herself in the process, but continued to attack. The INDIANOLA was taking on water and could barely steer, so Brown beached her on the west bank where she could be reached by Union forces. However, when the ironclad touched shore the rebels boarded her, tied ropes to her, and towed her across the river, where she sank in the shallows. The Confederates immediately set about trying to raise her.

A Union sailor who had managed to jump overboard when the INDIANOLA touched the west bank made his way north, to give Porter the bad news on 26 February. Porter was appalled. His plan for river raiding had backfired disastrously, with one of his best wooden ships now fighting for the rebels, and his most powerful ironclad being salvaged to do the same. He had given the Confederates the means to effectively resist any further downstream movements by the Union river navy. Worse, all of the other Federal gunboats were away, assisting Grant in his experiments.

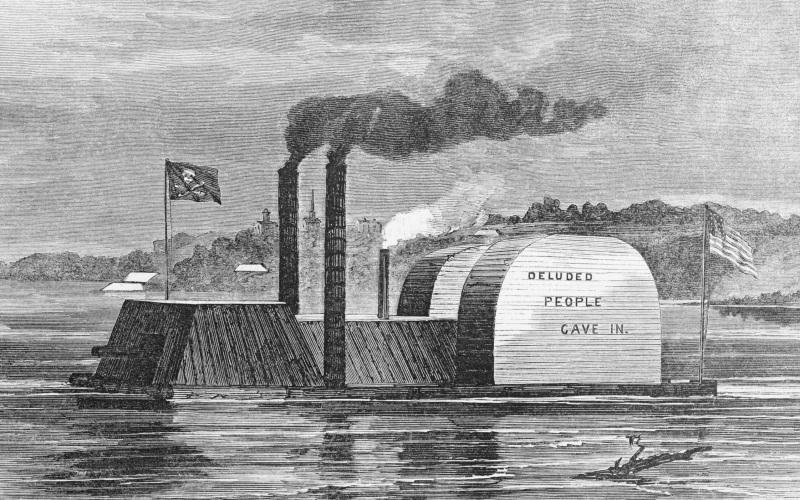

With nothing else available, Porter resorted to deception. He took every man available and set them to work building a dummy ironclad, using as its basis a old barge that was extended with rafts. Within a day the mock warship had been completed, with a pilot house made of planks and canvas, two empty paddle-wheel boxes, guns made of logs, and twin smokestacks built of stacked barrels, each capped with smoke pots. Two old skiffs were mounted for a convincing touch, and the whole thing was painted with tar. The cost of the project, it was proudly reported, was $8.63.

When the sun fell, the smoke pots were lit and the vessel set adrift to float past Vicksburg. The rebel gunners fired everything they had at her but she moved on steadily, as if completely unharmed. The next morning the fake warship grounded herself on the west bank, and Sherman's soldiers pushed her off with a cheer. Moving downstream, she encountered the QUEEN OF THE WEST steaming upstream, which promptly turned about and ran downstream to spread the alarm. The Confederates couldn't hope to take on a big Union ironclad in broad daylight, and besides, they were still nursing injuries from the fight with the INDIANOLA.

The four rebel gunboats fled immediately, leaving the Confederate lieutenant in charge of salvaging the INDIANOLA to destroy her, rather than let her fall back into Union hands. The smoking monster steaming downstream halted two miles (3.2 kilometers) upstream of the INDIANOLA. The lieutenant held his ground until nightfall, wondering what the Yankees were up to, when he finally decided to carry out his orders. He had the two 11-inch guns faced muzzle-to-muzzle and fired them into each other using a slow fuze, then burned what was left.

The next day, the threatening Union ironclad was where she had been the night before. It made no movement nor gave any sign of life. Finally, curiosity got the better of the rebels, and they went out in a rowboat to investigate, to find out that they'd been had. They also found a sign nailed to the side of the Quaker warship:

DELUDED PEOPLE CAVE IN.BACK_TO_TOP

* Even while William Tecumseh Sherman and his men labored to cut off Vicksburg by diverting the Mississippi away from the city, Grant was considering other options.

On the west bank of the river, just south of the Arkansas border in Louisiana, was a body of water known as Lake Providence. It had once been a bend in the Mississippi, but had been cut off by the river's meanderings. A study of a map of the river systems in the region hinted that Lake Providence might in fact live up to its name: it was drained by a short outlet named Bayou Baxter, which flowed into a longer waterway named Bayou Macon -- and so on, through a network of rivers that eventually ended up in the Red River, and then the Mississippi itself.

Grant wondered if reconnecting Lake Providence to the Mississippi might open a back-door route around Vicksburg to support a combined attack on Port Hudson. Once the southern linchpin of the Confederate-controlled stretch of the river fell, the northern one, Vicksburg, should quickly follow. He estimated that the work required to accomplish the task would be a fraction of the effort Sherman was expending on his futile canal.

Grant ordered Major General James MacPherson to come immediately downriver from Memphis with a division and begin the work. MacPherson was highly qualified for the task: he had been top of the West Point class of 1853, had extensive experience in engineering projects, and had returned to the Academy to teach engineering. MacPherson was youthful, handsome, smart, pleasant, highly competent, and was on a rocketlike rise up through the ranks after starting out as Grant's engineering officer. At the time of the battle of Shiloh, MacPherson had only been a lieutenant colonel.

MacPherson threw himself into his work, having his men drag a steamship over the levee from the Mississippi into Lake Providence so he could scout out the area. The practical difficulties turned out to be considerable. The waterways out of Lake Providence proved to be choked with cypress trees, and though McPherson's ingenious men came up with a barge-borne circular saw that they used to cut off stumps below the waterline, such an approach was obviously too laborious to be practical on a greater scale.

The attempt to find a waterway through Lake Providence was called off after two months of effort, though Grant had realized it was a dead end well before that. He kept the men at work partly to distract the Confederates, as well as simply to give his soldiers something to do. They seemed to take it in that spirit, the soldiers taking turns sawing out cypress stumps, and enjoying the fishing in the meantime. McPherson and his staff took their little steamship out on moonlight excursions, enjoyed the music of the regimental band, and returned to the landing of a plantation house they had commandeered, where they could enjoy its well-stocked wine cellar.

* In the meantime, Grant was pursuing a second back-water approach to the problem. The region north of where the Yazoo flowed into the Mississippi was crisscrossed with streams and small rivers, and laced with swamps. The region was known locally as "the Delta" -- though it was something of the reverse of a conventional river delta, with the waters converging instead of diverging.

Of particular interest was the fact that far north of the confluence of the two major rivers -- at a place just south of Helena, Arkansas -- the Mississippi had once connected into this network in a way that had allowed steamships to make their way all across to the Yazoo. This connection had so been known as Yazoo Pass, but it had been sealed off by the shifting of the Mississippi's course in the 1850s.

Grant felt that if he could get his gunboats and transports into the Delta network, he could bypass Confederate defenses protecting the lower reaches of the Yazoo and launch an attack on Vicksburg at Haines' Bluff, upriver of Confederate defenses. At about the same time Grant ordered McPherson to begin work on the Lake Providence route, Grant sent Lieutenant Colonel James H. Wilson, his chief topographical engineer, to scout out the possibilities of the Yazoo Pass route. Wilson was a West Pointer from Illinois, 25 years old, who had served as an aide to McClellan at Antietam. On transferring West, Wilson had been doubtful of the dumpy-looking Grant, who hardly looked half the soldier that McClellan did -- but Grant talked less and accomplished more than Little Mac, and gave Wilson plenty of free leash that earned the younger man's respect.

Wilson decided to re-connect the Mississippi with the Yazoo Pass, and on 2 February the Federals blasted the levee separating the two. The result was spectacular, "water pouring through it like nothing else I ever saw except Niagara," as he wrote later. A few days later, after the torrents had subsided, he took a steamboat down Yazoo Pass into Moon Lake, about a mile from the Mississippi, and five miles (eight kilometers) through the pass beyond that. Wilson became extremely excited over the possibilities and wrote Grant, infecting him with enthusiasm. Wilson already had a division at his disposal, and Grant ordered another one to join the first. However, after his initial quick progress, Wilson found that the dozen miles of Yazoo Pass on the far side of Moon Lake were more challenging: the waterway was not only narrow, with great oaks and cypresses hemming in his vessels, but local Confederates had brought in slaves to cut down some of the great trees as barriers to block Yankee movements.

It took Wilson most of the rest of the month of February to clear the way, using parties of hundreds of soldiers to drag the huge trees off on big navy hawsers. Once past these obstacles, he would then have access to the Coldwater, which was said to be a perfectly navigable river that could handle any vessel available to the Federals in the theater of operations.

* Events mercifully finally put a stop to the canal-digging efforts of Sherman and his men across the river from Vicksburg. In early March, the rising Mississippi broke through the earth dam protecting the northern end of the cut, flooding the Union men out of their camps. The Federals tried to return when the water went down -- only to come under fire by the Confederates across the river. Grant called the whole thing off.

It was obvious by that time that the Lake Providence route wasn't going to work, either. The only real option for the moment was the Yazoo Pass route. Lieutenant Colonel James Wilson, after laboring to clear Yazoo Pass all the previous month, finally cut through, and in the first week of March he and his men accompanied ten armed vessels, including two ironclads, to make a back-water attack on Vicksburg. 22 transports were to follow once the gunboats cleared the way. Wilson wasn't actually in charge of the expedition; the vessels were under the command of Navy Lieutenant Commander Watson Smith. That was problematic, since Smith was clearly ailing at the time.

The exercise proved a little more difficult than expected. While the Coldwater was wider and deeper than Yazoo Pass, and the Tallahatchie that it flowed into wider still, they were still cramped waterways for large steamships. Squeezing around tight bends was troublesome -- worse, overhanging branches knocked down smokestacks, and tore off anything not nailed down tight.

The real trouble came after they had proceeded more than a hundred miles (160 kilometers) downstream, when they encountered a crude fortification built by the rebels, standing directly in their path. Fort Pemberton, as the Confederates called it, had been thrown together from sandbags and cotton bales, and mounted nothing more potent than a 6.4-inch (16.3-centimeter) rifle along with some smaller artillery. There were 1,500 rebels there, under the command of Major General William W. Loring, a one-armed veteran of the Mexican War. It wasn't much of a fort in itself, but it was sited so that any vessels coming downstream would have to do so in single file, exposed to continuous fire at long range, and with no way to bring more than one or two guns to bear in return. The banks of the Tallahatchie were flooded, one of the consequences of blowing the levee, and too much of a quagmire to allow infantry to assault the fort.

On 11 March, the two ironclads in the Union fleet, the CHILLICOTHE and the DEKALB, moved downstream to take Fort Pemberton under fire. Unfortunately, while the gunners on the CHILLICOTHE were loading their 11-inch (28-centimeter) guns, a rebel shell slammed through the gun port into the turret, setting off the Federal shells and mowing down the gun crew. Lieutenant-Commander Smith, who had been showing increasing signs of agitation as he moved his fleet downstream, went into a frenzy of distress and ordered the two ironclads to fall back. His men described his behavior as "incoherent".

The ironclads tried again on 13 and 16 March, to take a brutal pounding. Both vessels were badly shot-up, while they had hardly scratched the Confederates. "Give 'em blizzards, boys!" Loring called out to his gun crews, and from that time on he would be known as "Old Blizzards". On the 17th Smith, recovering his senses for a moment, called it quits. Wilson protested loudly, but Smith sent his fleet back upstream anyway. Two days later, the little fleet ran into the second division that Grant had committed to the project, under the command of Brigadier General Isaac Quinby.

Quinby was the ranking officer and didn't want to give up without investigating further, so the entire fleet went back downstream, spending about two weeks there while Quinby inspected the situation. In early April, he agreed that the matter was a lost cause. In fact, by this time even Wilson had given up, since the rebels had brought up a steamship to sink and block the river if the Federals tried to come through. Interestingly, the blockship was the STAR OF THE WEST, whose attempt to resupply Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor in 1861 had helped set off the war.

The Union vessels went back from where they had come from. Wilson was apprehensive of his standing in Grant's staff because of the failure of the project, but Grant was undiscouraged. Porter relieved the ailing Watson Smith and sent him back north; he later died in delirium in a sanitarium.

* Grant's sympathy with Wilson was partly based on the fact that Grant had been finding out for himself what Wilson had been going through. After the loss of the QUEEN OF THE WEST and the INDIANOLA, David Porter had wanted to take action to restore his self-assurance and public reputation, and so he conceived his own back-door route to attack Vicksburg. The heavy rains and Wilson's destruction of the Yazoo Pass levee had resulted in flooding most of the lower Yazoo Delta. Porter believed that he could snake a river fleet through the twisty bayous of the region, and land it upriver of the Confederate defenses at Haines' Bluff.

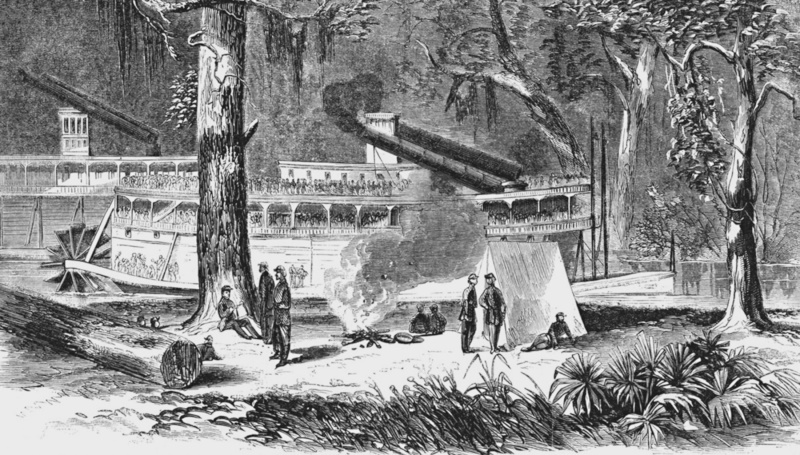

Porter took Grant on a short excursion through these bayous, navigating between flooded treetops down roads covered with 15 feet (4.6 meters) of water, and Grant was so enthusiastic that he issued immediate orders to begin the "Steele Bayou" expedition, as it would come to be known. Sherman, more or less unemployed since the abrupt end of his canal-building efforts, was ordered to provide troops for the project, and slogged through the mud with a division to make contact with Porter's little navy on 16 March. Sherman's troops boarded the transports accompanying Porter's fleet, which immediately steamed forward.

However, as James Wilson and Watson Smith had found out with their own plans, the idea looked better on a map than it did in practice. The bayous were narrow and tangled, resulting in damage to the vessels and a rain of vermin -- mice, rats, snakes, lizards, and cockroaches -- from the trees. Sherman's men swept them off the decks; encounters with agitated wildcats who had been rudely knocked from the branches resulted in exciting confrontations.

Porter's gunboats ranged well ahead of the transports. The transports were too wide to fit through the narrow passages, and the infantry had to help clear the way for them through the tangle. On 19 March, the gunboats got into trouble. Encountering a wide, green patch of water at daybreak, Porter asked some slaves on the banks if it were safe to enter. One replied that it was nothing but a patch of willows, and that the vessels shouldn't have any trouble.

That might have been true for rowboats, but when Porter steamed his ironclad into the patch of water, it quickly became snarled tight in the willow branches. The vessel was all but defenseless if the Confederates wanted to seize it, since the banks blocked the ship's guns. Porter set up four smoothbore howitzers on an Indian mound for self-defense, and put his men to cutting the ironclad out of its trap.

Suddenly, the ironclad and the gun crew on the mound came under long-range artillery fire. The Confederates had two six-gun batteries bearing on them from opposite directions. Porter managed to return fire using mortar boats. Desperate for help, Porter found a contraband, who he addressed as "Sambo", and who replied with offended dignity: "My name ain't Sambo, sah. My name's Tub." With names all straight, Porter paid Tub a half dollar to carry an unintentionally humorous message back to Sherman: "Dear Sherman: Hurry up, for Heaven's sake. I never knew how helpless an ironclad could be steaming around through the woods without an army to back her."

Tub honored his bargain with Porter, finding Sherman late that night. The slave then led Sherman and his troops first on a steamship, and when the steamship couldn't proceed further, on foot through the muck. Drummer boys carried their drums on their heads, and the men slung their cartridge belts around their necks to keep them dry. They spend a day and another night on the wretched slog; the soldiers finally came to Porter's aid on the morning of Sunday, 22 March. Brisk fighting was in progress, with rebel and Union artillery trading shots. Confederate soldiers were trying to sneak around and chop down trees to cut off the stranded gunboats.

Sherman's men chased off the rebel soldiers, and then made contact with Porter. By that time, Porter had managed to free his vessel. Their rudders removed, the ships of Porter's fleet were trying to steam backwards to where they had come from, since there was no room to turn around. Porter was relieved to get the help, since he had feared being encircled and captured. Sherman wrote later: "I doubt if he was ever more glad to meet a friend than he was to see me." Both men had gone through enough, however, Sherman calling it "the most infernal expedition I was ever on." The gunboats continued their backwards progress; Sherman's soldiers mocked the Navy crews mercilessly, who cursed them angrily.

The fleet finally managed to inch its way back to the mouth of the Yazoo, where their damage was repaired, with the vessels painted and polished back to a shine. Despite the whole expedition being a wild fiasco, or more likely because of it, the Steele Bayou expedition became something of an adventure that its participants looked back on with a bit of pride.

Sherman's canal had failed; McPherson's Lake Providence route had gone nowhere; Wilson's expedition down Yazoo Pass had run into a dead end; and so had Porter's meanderings through the Yazoo Delta. Grant ordered McClernand to investigate another canal, but that project went nowhere fast when the Mississippi began to fall again.

Grant later claimed that he hadn't been very serious about the back-water experiments, but the reality was that he was desperate to find some way to crack Vicksburg. The failure of the experiments did not go unnoticed in Washington DC; coupled with ongoing concerns about his drinking, Grant's political standing was shaky. However, if he was discouraged, he didn't show it much, and he was certainly nowhere near giving up. A Union officer who had been taken prisoner during the Steele Bayou experiment, was asked by his captors: "Hasn't the old fool tried this ditching and flanking five times already?"

The prisoner replied: "Yes, but he has thirty-seven more plans in his pocket."

BACK_TO_TOP* Down the Mississippi, Nathaniel Banks had been similarly considering what he might do to isolate or capture Port Hudson, the linchpin of the Confederate Mississippi corridor in the south. Unlike Grant, however, Banks was much more worried about what the rebels might do to him instead of the reverse, and so he ended up doing little.

His naval counterpart, David Farragut, was made of much more fiery stuff. On hearing of Porter's loss of the QUEEN OF THE WEST and the INDIANOLA, Farragut took it as a personal insult. He resolved to move upstream immediately past the high bluffs and guns of Port Hudson and show the rebels just who the boss really was. He had seven wooden vessels: the heavy warships HARTFORD, RICHMOND, and MONONGAHELA, the old side-wheeler MISSISSIPPI, and three gunboats. Farragut planned to make the run during a moonless night to limit his casualties. Banks wasn't to be left completely out of the action, however. He was to lead a feint on Port Hudson with 12,000 men to distract the defenders, while Farragut prepared for his dash.

After darkness fell on 14 March, the fleet steamed upriver, with the HARTFORD leading the way. The ships moved quietly, and remained undetected until the HARTFORD cleared the first battery below Port Hudson -- when she was spotted by Confederate pickets, who lit pitch-pine bonfires and set off rockets to alert the gunners on shore. The night was misty and windless, and the exchanges of cannon fire between the ships and the guns on the bluffs above the river covered the river with black smoke, providing a smokescreen for the ships.

The HARTFORD made it beyond the batteries with three casualties, along with damage to her spars and topdeck. Unfortunately, the RICHMOND was struck in her engine room and lost steam; she floated back downstream, to be followed by the MONONGAHELA, which suffered an engine failure and other damage. It was the side-wheeler frigate MISSISSIPPI -- which had been Commodore Matthew Perry's flagship during the US Navy expedition to Japan a decade before -- that took the worst beating, taking hits not only from the rebels but, in the confusion, from the RICHMOND as well, and then ran hard aground, right in full view of the rebel gunners.

Pounded by shot and shells and stuck tight, her captain ordered the crew to abandon ship, then set the MISSISSIPPI on fire. She burned until morning, then slid off the mud bank where she had grounded, floated in flames downstream past the injured ships nursing their wounds below the town, grounded again, and blew up. Banks' men had arrived too late to seriously distract the Confederates, but they got a spectacular fireworks show. Only three of the seven vessels that started out made it past Port Hudson, and there were 112 casualties, with 35 men killed outright. Still, Farragut was now past the guns of Port Hudson. The three ships steamed upriver for the day and the following night, dropping anchor near the mouth of the Red River when the sun came up again.

The rebel ram WEBB and the captured Union ram QUEEN OF THE WEST had retreated back up the Red after the INDIANOLA fiasco. They had been heavily damaged in the fight with the INDIANOLA, and were in no condition to take on Farragut -- but in any case, Farragut rigged up further protection for the HARTFORD by using logs and anything else he could find as armor, and then continued upriver in hopes of making contact with Porter's vessels.

Porter was thinking along much the same lines. He sent two steam rams, the SWITZERLAND and the LANCASTER, downstream past Vicksburg on 25 March to link up with Farragut. The LANCASTER took several hits, while the SWITZERLAND was hit so badly that she broke up and sank. Despite the losses, Porter's plan for a naval blockade between Port Hudson and Vicksburg was a reality. The Federals had now effectively cut commerce between the eastern and western halves of the Confederacy. Unfortunately, as long as the rebels maintained their fortresses at each end of the corridor, they in turn blocked commerce from the American Midwest into the Gulf of Mexico. It was up to Grant to put an end to this stalemate.

BACK_TO_TOP* At the beginning of April 1863, Grant was in a difficult position; despite a lot of wild activity, he had failed to take Vicksburg. One Cincinnati editor called him in a correspondence to Secretary of the Treasury Chase "a jackass in the original package" and "a poor drunken imbecile". Lincoln said: "I think Grant has hardly a friend left, except myself." The President had assessed Grant as a general who, unlike most of the others, really wanted to inflict pain and injury on the rebels. The President valued Grant, though his patience in the general was hardly unlimited.

Actual reports from those in Grant's vicinity on the subject of the general's sobriety tended to be wildly conflicting, some claiming he was always drunk, others saying he never touched a drop. The truth appears to be that he would go on binges every rare now and then, generally when he had been away from his wife and family for a long period of time. Secretary of War Stanton was suspicious, as he always was, and so he sent a spy to keep an eye on Grant. Charles Dana -- who had been a reporter for Horace Greeley, the prominent and eccentric editor of the NEW YORK TRIBUNE newspaper -- was sent west under the cover of an inspector for the pay service, though he was really a personal informant for Stanton. Dana arrived in early April, and was instantly recognized as a spy. Some hotheads wanted to throw him in the river, but Grant took a relaxed view of the situation, and did everything he could to make Dana feel at home.

It proved that Stanton could not have done Grant a bigger favor. Dana quickly took a strong liking to Grant, writing that Grant was "the most modest, the most [politically] disinterested and the most honest man I ever knew, with a temper that nothing could disturb." Dana also thought highly of Sherman and MacPherson, and could not say enough good about them, while he could not speak enough ill of McClernand.

Most of Grant's men liked their commander as well. Grant was undistinguished in appearance, reserved, common-sensible, with no "superfluous flummery". He was no stickler for military formality, nor did he court favor with the soldiers. Rather than cheers, most of the soldiers greeted him with a simple: "Pleasant day, General." -- or: "Good morning, General." -- and he would give them a simple nod in return.

Grant was spending nearly all his time holed up in his room on board the headquarters boat, the MAGNOLIA, puffing on cigars and studying maps. MacPherson grew concerned about Grant's obsessive labors, and tried to draw him out of the room for a drink or two one night -- but Grant gently suggested that if MacPherson really wanted to help, he should leave a dozen cigars and leave him alone. MacPherson did so, and Grant returned to his work.

Grant wasn't the sort of general to leave an army idle when the weather was improving enough for campaigning: not only was the upkeep of an army expensive, but the longer Grant waited, the deeper the Confederates would dig in, and the Lincoln Administration's impatience with delay was by this time obvious. Unfortunately, Grant's options were limited.

The straightforward thing to do was to pull back to Memphis, and try once more to advance south along the Mississippi Central Railroad, as he had done in December. However, that would be politically unwise. Falling back to Memphis would be clearly seen as another Union defeat, and besides, rebel cavalry would likely descend on his rear, just as they had before, once he advanced. He considered a frontal attack, but decided it would be suicidal. Pemberton's defenses were simply too strong.

Grant finally came up with a solution. Instead of moving north again, he would move his army south, down the west bank of the Mississippi, then run steamships past Vicksburg to shuttle the troops across the river. The army could live off the land as they advanced on the rebel fortress from the south.

Sherman and MacPherson protested bitterly. Pemberton had 60,000 men under his command, while Grant could only provide 33,000 of his own men for the offensive; although Grant had over 100,000 men in total, most of them were committed elsewhere. Furthermore, the attackers would be fighting with an uncertain supply line, and with no safe escape route should things go wrong. Ironically, McClernand was wildly enthusiastic about the idea, since it matched his own inclinations toward the dramatic. Grant didn't much care if anyone liked it or not -- he'd made up his mind. Sherman and MacPherson swallowed their misgivings out of loyalty to their commander.

* The first problem was to move the army 40 miles (64 kilometers) downstream from Milliken's Bend to New Carthage, on the west bank of the Mississippi 20 miles (32 kilometers) south of Vicksburg. Unfortunately, as if to confirm Sherman and MacPherson's fears, the rains kept falling, with the soldiers making slow progress on the muddy roads. Grant was in a hurry, and that meant that at least part of his army would have to be shipped downstream on the river, right under the guns of the Confederates.

Grant had no authority to give Rear Admiral Porter orders, but Porter was enthusiastic -- though he told Grant that once the vessels went downstream, they would not be able to go back up again as long as the rebels held Vicksburg. They would be sitting ducks, struggling against the current while rebel gunners took careful aim at them.

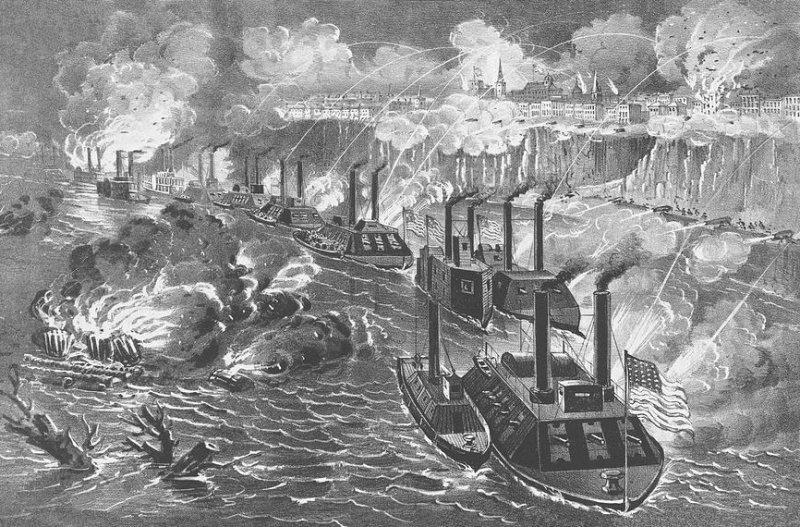

The first convoy consisted of seven armored gunboats; a captured rebel steam ram; and three transports. It made the run under the guns on the night of 16 April 1863, while Grant, in the company of his wife Julia and two of his sons, watched the action from upstream, just out of range of rebel guns.

Porter had ordered all pets and poultry kept by the crews to be left behind, lest they make noise and alert the rebels. The steam-engine exhausts were also rerouted to vent into the paddle-wheel housings to muffle them, and the vessels were to move as slowly and quietly as possible. Bales of hay and cotton, grain sacks, and logs were piled up on decks as improvised armor, while teams stood by under decks with cotton wads and gunny sacks to plug leaks.

A grand ball was being held that night in Vicksburg; in fact, spies had told Porter of the event, and he hoped it would distract the Confederates from his convoy. However, rebel pickets, who were patrolling on the river in skiffs, detected the steamships immediately. The ball was broken up, and the soldiers ran to their guns to begin pouring fire on the Union vessels. The Confederates lit barrels of pitch pine on the east side of the river, while some rebels threaded their way across the river in skiffs under the storm of metal to set piles of wood and buildings on the west bank on fire. The steamships were lit up "as if by sunlight", as Grant's son Fred put it, reducing the scene to a vision of Hell.

It took two and a half hours to run the gauntlet. The Confederates fired over 500 shots at the fleet, but casualties were minimal -- Porter had the fleet skirt as close to the Vicksburg shore as possible, believing correctly that rebel gunners would have difficulties depressing the guns in the batteries above the shore low enough to hit the vessels. Only one transport and a few barges failed to make it downstream to New Carthage, and all those on board were saved; no one was killed, and only 13 had been wounded. The fleet was greeted enthusiastically by Sherman, who went aboard the gunboat BENTON to greet his friend Porter: "You are more at home here than you were in the ditches grounding on willow trees."

Grant arrived in New Carthage by horse the next day. A week later, six more transports made the run. One, the TIGRESS, was sunk, but there were no men killed and only a few wounded. The campaign was getting off to a promising start. The TIGRESS had also carried three reporters. Sherman hated reporters, one paper saying he "foamed at the mouth" on the subject; he assumed the men had been drowned, and was pleased that there were three less "dirty newspaper scribblers" walking the Earth, proclaiming: "We'll have dispatches now from Hell before breakfast!" The reporters had actually been captured. One got away immediately; the other two were imprisoned for 19 months before they managed to escape.

BACK_TO_TOP