* The measures Congress took to create a new order in the South, in the end, failed, through a lack of support in the North, widespread resistance in the South, and judicial accommodation of Southern aims. The result was the creation of a system of "Jim Crow" segregation in the South that would persist for almost a century.

* By 1870, there were some indications of a return to normalcy in the South. Cotton production had almost returned to its 1859 level, and would well exceed that a decade later. Mills were rebuilt, new industry was established, and the rail system was rebuilt and extended.

However, any more than a casual inspection left a more discouraging impression. The economic expansion of the South lagged well behind the rest of the Union, which was undergoing rapid growth. In 1860, 30% of America's wealth was concentrated in the South, but by 1870 the proportion had dropped to 12%. Although the war had badly injured the South, it is highly arguable that long-lingering postwar Southern economic backwardness was completely the result of Northern malevolence. Southerners, always strong in their traditions, had never like the pushy capitalism of the North, preferring to retain the old ways of doing things as much as possible. Indeed, it could be argued that had the capitalists of the North been more interested in the South, the South's postwar economic development wouldn't have stagnated as it did.

The class structure, though it had been weakened, remained in place. Large plantations survived, in a modified form, with the land worked by "share croppers" and "share tenants". Share croppers were usually blacks who essentially rented their land, homes, and equipment from a landlord, and paid the landlord a portion of their crops, usually a third to a half. Share tenants were similar, but were generally white, and usually provided their own equipment. There were many variations on these concepts.

Some of the planters found the new order agreeable. Southerners had long made much of the "social security" net provided by slavery, with the slave-owner taking care of children, the sick, and the elderly, and however well or poorly they did so, it was still more expense than they had using share croppers. The end of slavery actually meant cheaper labor -- and now even the poorer farmers who couldn't have afforded slaves were able to hire on help when they needed it.

The system basically evolved out of the simple lack of cash available to Southerners, not any grand capitalist conspiracy to exploit the workers. There was no money to pay workers, so everyone was reduced to a ramshackle system of payments in kind and credit. Bankers and merchants became involved with the credit system and took out liens on property as collateral. The system was insecure, since any major crop failure hit everyone in a region very hard, and led to a stifled economy, with few avenues for financial or social advancement.

* Southerners would, for good reasons, take a long time to forget their defeat and consequent humiliation by the North after the war, but occupations of rebellious provinces can last generations, and are often marked by monstrous atrocities. Although the Federal occupation of the South was no picnic:

Even more surprisingly their property, except for slaves, wasn't seized. The indignities of the occupation were less a consequence of vindictiveness than of the simple bumbling of Northern outsiders engaged in half-baked attempts at "social engineering" of the renegade states, in particular attempts to push racial equality.

Farmers, poor whites, and the middle class violently hated the idea of black equality, since it meant that blacks would then come into their society as peers and competitors; since they regarded black people as inferiors, they felt very threatened. The idea of a white person being employed by a black man was a particular outrage.

The Southern aristocracy also regarded black people as inferior, but to an extent they regarded the white "lower orders" with the same contempt. The aristocracy hated the idea of any of the poor classes being given the right to vote, and their dislike of black suffrage was a matter of degree, not kind. However, at the same time, the upper classes knew they that blacks would not be admitted into their society on an equal basis any more than poor whites would, and also felt that they would be able to manipulate blacks to vote in whatever way they felt convenient. It was easier for wealthy Southerners to adjust to the idea of black suffrage.

The Radical Republicans imposed black suffrage on the conquered states with little understanding of the realities involved. By using the black vote, they were able to sustain Republican governments in these states for a time; in Southern legend, this was a time when their state governments were passed over to black people, but in fact blacks did not dominate state governments even in states like Mississippi, where the number of black citizens substantially exceeded that of whites.

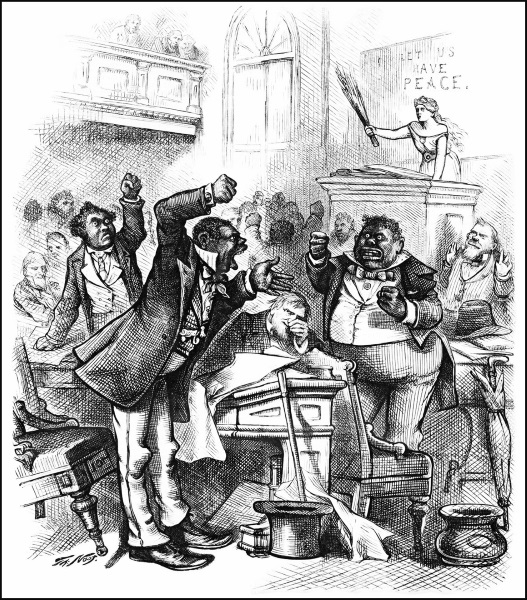

The only state in which blacks were ever a majority in a state legislature was South Carolina. Ironically, it was this legislature that helped establish the myth of "black tyranny" through the efforts of a muckraking Northern journalist named James Shepherd Pike. Pike was a strong anti-slavery man who had been the ambassador to the Netherlands in the Lincoln Administration, but he was also a solid white supremacist. Pike went to South Carolina in 1873, where he observed the black legislature in action, and wrote about the ignorance and corruption he saw in newspaper articles that were widely circulated and later collected in a book titled THE PROSTRATE STATE.

Pike spoke of South Carolina government as being under the control of a "mass of black barbarism" and warned of the "Africanization" of the South. Despite that, in no state was a black man elected governor. Blacks became lieutenant governors only in Mississippi, Louisiana, and North Carolina. Blacks were also greatly under-represented in local offices, with only one black mayor and twelve black sheriffs in all of Mississippi. Only about 20 blacks were elected to the House of Representatives during Reconstruction.

The black politicians who did acquire influence in this period were a mixed lot. One, Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback, was a classic corrupt politician. He was said to be the son of a Mississippi planter and one of the planter's slave women, whose father had given him his freedom and sent him north. He apparently had spent some time in the employ of a Mississippi riverboat gambler, who taught Pinchback every crooked trick he knew. Pinchback went South after the fall of Louisiana to the Union and served as lieutenant governor and even for a time as acting governor -- where he used his post to line his pockets and promote his cronies.

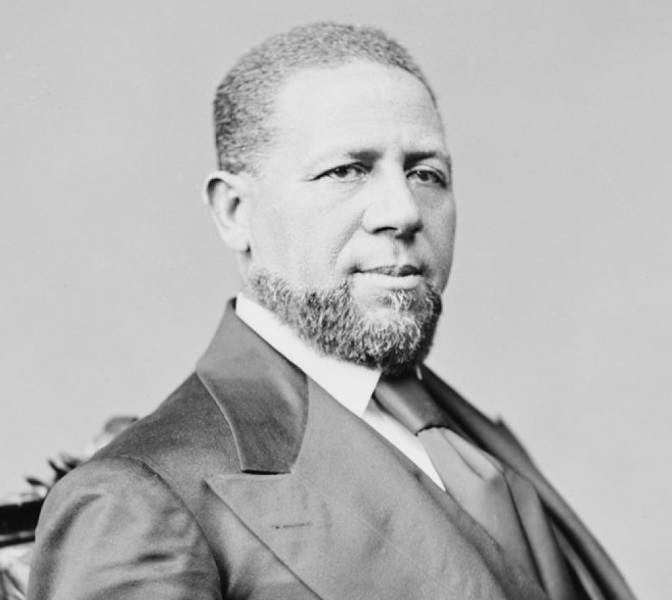

Of course, not all the black politicians were crooks. Hiram R. Revels became senator from Mississippi, becoming the first black man in the Senate -- ironically, taking the seat that had once been occupied by Jefferson Davis -- and was followed in his seat by Blanche Kelso Bruce, making them the only two black senators of the 19th century. They had both been born in the South and had gone North as young men. Revels had been born free, and obtained a degree from Knox College, while Bruce was a freedman who got his degree from Oberlin. They were both committed to furthering the rights of black people, but at the same time were concerned at inventing a system where black and white Southerners could live together amicably. Bruce was the last black senator for 90 years.

One of the most prominent black leaders in the postwar South was Dr. Louis C. Roudanz, a free black of Louisiana who had been educated in Paris and was a very wealthy man. Roudanz founded the first daily black newspaper, the NEW ORLEANS TRIBUNE, and crusaded for land reform. He blasted the Republican leadership as well as the Democrats, saying of Republican leaders that their "sole motive is greed" -- an observation that would be supported by events.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Republican state governments of the ex-Confederate states were in general heavily controlled by white Southern Republicans, called "scalawags"; and by opportunistic Northerners who had come South with their possessions in carpetbags, and so were known as "carpetbaggers".

The scalawags have been historically stereotyped as low-born and unscrupulous men on the make, but in many cases they were members of the traditional Southern power elite who felt that turning Republican was a practical and useful way to further their interests. One of the most prominent of the scalawags was Governor Joseph Brown of Georgia, who had spent much of the war doing everything to spite the Confederate government in Richmond in the name of State's Rights. With the Republicans being the power in the land after the war, he became a Republican, and when Republican power faded away in Georgia, he became a Democrat and a Democratic senator in Washington. Joseph Brown was being true to his fundamental principle: the empowerment of Joseph Brown.

Others scalawags, such as James L. Alcorn, the first Republican governor of Mississippi, went Republican simply because that was the new reality. Alcorn believed in the rights of the black man: "I propose to vote with him; to discuss political affairs with him; to sit, if need be, in political counsel with him; and from a platform acceptable alike to him, to me, and to you, to pluck our common liberty and our common prosperity out of the jaws of inevitable ruin."

Scalawags were often very willing to recognize the rights of black people as a means to the end of restoring the tattered fortunes of their states; it was a lot for them to swallow, but they understood the necessity. However, the scalawags were gradually overshadowed by the carpetbaggers. Scalawags might court the black people's vote, but they would not associate with them. Carpetbaggers were willing to mingle with black people socially.

Carpetbaggers were also stereotyped as corrupt scoundrels, but they were a varied lot as well. Some would eventually melt into local Southern society, adopting much the same attitudes as their neighbors and becoming more or less accepted as Southerners themselves. Others were idealistic, sometimes too much so. Albion W. Tourgee of Ohio went South to North Carolina, where he tried to nudge the state's society to more egalitarian lines. He failed in this exercise, went back to Ohio, and wrote a semi-autobiographical novel titled A FOOL'S ERRAND, in which Tourgee admitted:

QUOTE:

We tried to impose the idea of civilization, the idea of the North, upon the South at a moment's warning. We presumed that, by the suppression of rebellion, the Southern white man had become identical with the Caucasian of the North in thought and sentiment; and that the slave, by emancipation, had become a saint and a Solomon at once ... it was A FOOL'S ERRAND.

END_QUOTE

Albert Morgan came from Wisconsin to Yazoo City, Mississippi, where he and his brother tried to run a leased plantation. They failed in this, and Morgan focused on politics. He openly associated with black people, and with their help was elected state senator and sheriff. The old sheriff refused to give up his office, leading to a gun battle in which he was killed. Morgan proved to be an honest and capable sheriff, but he had stepped on the toes of the whites through his race mingling, particularly when he married a mixed-race woman from the North; she was only an eighth black, but the tale was a sensation all over America. The whites banded together, took up arms, and ran him out of town.

Milton S. Littlefield, who had been an Illinois general during the war, better fit the stereotype of the carpetbagger. He went to North Carolina in 1867 and also worked in Florida, involving himself in shady and profitable railroad deals. However, his deals involved prominent local figures, and in fact he was generally no more than a front man, since he had the personality of a born salesman. Littlefield left North Carolina when the state went back to Democratic rule. The North Carolina authorities tried to extradite him, but according to a story, Littlefield had no difficulty with a visitor who had come to demand that he go to North Carolina to stand trial. Littlefield gave the visitor a set of documents identifying prominent North Carolinans who would have to stand trial as well, and the visitor replied: "General, I respect your condition. I do not think we will trouble you any more."

Another opportunistic carpetbagger was Henry C. Warmouth, who went South after living in Illinois and Missouri, to become governor of Louisiana. Warmouth was a pragmatist, who implemented what he perceived as prudent policies while also pursuing his own interests. He was accused of corruption -- to which he replied that he hadn't been any more corrupt than the norm for Louisiana, accurately pointing out that "corruption is the fashion down here." Louisiana politics had been dirty long before the war, still have a reputation for dirtiness today, and some have suggested that Louisiana corrupted Warmouth instead of the other way around. After the end of Reconstruction, Warmouth settled down in Louisiana as a sugar planter, dying in New Orleans in 1931.

* Corruption was commonplace in the South during Reconstruction. There was truth in Pike's stories of the corruption of the black South Carolina legislature, but corruption was impartial, tainting black and white, Republican and Democrat. In fact, it was just as bad in the North, or worse because there was so much more to steal. When excerpts from THE PROSTRATE STATE were read on the floor of the US House of Representatives, black Congressman Robert Smalls of South Carolina asked pointedly: "Have you the book there of the city of New York?"

It was boom times in most of the country, a "Gilded Age", when there were great fortunes to be had and everyone wanted a piece of the action. This corruption aggravated the financial troubles of the Southern states, and greatly undermined attempts to build a new society. Implementing great social reforms implied great expense, for example building new schools to educate freed slaves and their children -- an even harder sell, since public education for whites hadn't been common in the South before the war in the first place. State revenues were weak, and corruption siphoned off much of what was available. Under such circumstances, the various social factions ended up fighting each other for their own slice of a small pie, making class and race divisions even deeper.

The re-emergence of segregated society meant that barriers to blacks began to solidify through all of Southern society. Even some black leaders encouraged the trend to an extent, feeling that there was no reason why blacks should not have their own schools and facilities, not quite realizing that "separate" was unlikely to amount to "equal". As slaves, black people had gone to the same churches as whites, though the blacks had their own section, but now two sets of church systems arose, one for whites and one for blacks. Since blacks would be shut out of almost all other commercial or civic organizations, the segregation of churches had the unintended result of turning the black ministry into a leadership class.

Surprisingly, as the scalawags were forced out of power, many of them did not simply return to the fold of the Southern Democrats, instead attempting to form new initiatives with amazingly forward-thinking ideals. The most prominent of these new initiatives was the Louisiana Unification Movement of 1873. It was headed by Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, once a prominent Confederate general. Although Beauregard had suggested the execution of Union prisoners when Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862, as leader of the Louisiana Unification Movement he advocated a remarkable level of civil rights. The movement proclaimed full civil rights for all citizens, regardless of color, equal opportunities for employment by all citizens, and rejected segregation in education and access to public facilities.

While many influential businessmen, newspapermen, and clergymen supported the movement, they were a small minority. The mass of whites wanted segregation, and surprisingly support for the movement was weak among black people as well. Progressive concepts were simply much too far ahead of their time. The initiatives failed, and the scalawags had no other choice but to rejoin the Southern Democrats -- who were retaking control, state by state.

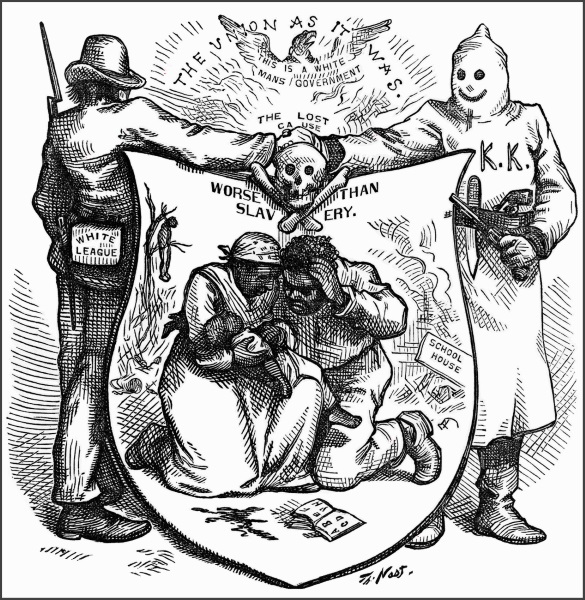

* The postwar civil-rights efforts were overbalanced by the rise of white-supremacy groups, such as the Pale Faces, the Sons of Midnight, the Knights of the White Camellia, and the Ku Klux Klan. Such groups would dress in white sheets as ghosts of rebel soldiers to terrorize and kill blacks, and run carpetbaggers out of town. Their ranks were full of ex-Confederate warriors who were no strangers to violence, the most prominent being Nathan Bedford Forrest -- a slave trader who had become a legendary cavalry general, one of the South's most energetic, resourceful, and ruthless warfighters. Forrest helped organize the Klan, said to have become the first "Grand Imperial Wizard" of the Klan. When approached by ex-Confederate officers about the concept, the story is that he replied: "That's a good idea, a damn good idea. We can use it to keep the niggers in their place."

Such lawlessness invited official retribution, and in 1870 the Federal government moved against the Klan and other terrorist groups. Well over a thousand men were arrested. Forrest, under examination in court, claimed that he had helped set up the organization to keep the peace, and that he ordered it disbanded after realizing that it had gone out of control. His admirers today insist he was telling the truth, some even claiming that he embraced racial equality. That is not easy to believe, but Forrest's "order" to disband the Klan was something of a joke, since he'd never had much control over it in the first place, and it was disintegrating under the wave of Federal arrests and rough justice. The organization, such as it was, disappeared.

However, white Southerners also formed legal organizations, called "Rifle Clubs" or "Red Shirts" or "White Leagues", that were more discreet and subtle in their efforts and so far more effective. Whites were pressured to toe the line, blacks were told to stay in their place. Economic pressure proved particularly useful, since any black or white person who didn't obey the rules quickly became unemployable, and was denied credit or loans. Violence was usually not necessary -- but when it was necessary, it was used without much misgiving. When election time rolled around, the White Leagues and their like would parade in the streets, heavily armed, and black folk would make themselves scarce if they valued their well-being.

There were riots every now and then, once again featuring one-sided casualty ratios, with many blacks killed and hurt or few, if any, whites harmed. There are tales that black women were often sexually assaulted by white males, with the law so indifferent to such incidents that it made no sense to protest. It is believable but not verifiable, careful records not being kept of such offenses.

BACK_TO_TOP* The men who had founded the Republican Party had been driven by anti-slavery ideals, but after the war passions had cooled, and increasingly the Republicans seemed infected by the "easy money" spirit of the times. The Presidential election of 1868 was a turning point of sorts, where the Republicans had to determine whether they were a party of ideals or of money.

The Republicans selected a candidate who seemed on the surface to represent the old ideals. At the Republican national convention, John "Black Jack" Logan -- a politician who, during the war, had been one of Grant's generals -- stood up and nominated General Grant for the presidency. There was wild applause, and Grant won the nomination with no real competition.

Although Grant had done much to destroy slavery and preserve the Union, any analysis of him as a presidential candidate showed he left much to be desired. He was a hero, yes, but he had no background in politics, and in fact his indifference to politics was one of the things that had made him successful as a general. He hadn't sought the presidency, and in fact the only political aspiration he had ever mentioned was to be mayor of his hometown of Galena, Illinois. Grant was a generally honest man, to be sure, but many who backed him for the presidency saw him as a convenient figurehead whose popularity would get him elected -- while they actually controlled things once he was in the White House.

The Democrats responded by nominating Horatio Seymour, previously governor of New York, as their candidate. The Democrats were in a difficult position. The Republicans were not only in positions of influence, but they were easily able to smear the Democrats as the "party of treason". The Democrats foolishly attacked the Reconstruction Acts, and in response the Republicans accused the Democrats of being sympathetic to rebellion. Grant won the election with 214 electoral votes to Seymour's 80, though the popular vote was very tight, with Grant beating Seymour by only a little more than 300,000 votes. Despite the posturing of the Republicans, public enthusiasm for their rhetoric was actually low.

* The Grant Administration did nothing to produce any more enthusiasm. Grant felt that his role as president was to implement measures passed by Congress, which reduced the administrative branch of government to dancing on the strings of Congressional intrigues. Any opportunity for civil rights was lost for almost a century, and Republicanism acquired its reputation as a party of and for the privileged that it has never quite managed to shake.

This last failing was in particular due to the financial scandals of the Grant Administration, generally regarded as one of the most corrupt in American history. The biggest scandal occurred when two financiers, Jay Gould and Jim Fisk, came up with a scheme to corner the gold market, control the price of gold, and make a killing. They used Abel Corbin, a lawyer who was a brother-in-law of Grant's, to lobby the president to discourage any sale of Treasury gold, which would completely disrupt the scheme.

Grant gradually became suspicious and on Friday, 24 September 1869, he ordered the sale of four million dollars worth of Treasury gold. Gould and Fisk did make a killing, though they had to move quickly to avoid being lynched by other speculators they had ruined. The day became known as "Black Friday". The scandal led up to the White House; Grant was not implicated himself in the Black Friday fiasco or the other scandals that followed, but many of his appointees were, and he often tried to protect them when they were accused of corruption.

Although the newspapers made much of the scandals, to the public and the Republican faithful they were just crooked business as usual; when the presidential election of 1872 rolled around, Grant was automatically nominated for a second term. However, a group of Republicans was so disgusted with the status quo that they bolted and form their own "Liberal Republican Party". The Liberal Republicans were a motley group, including some respected figures, but with many marginal figures of little credibility, most notably Horace Greeley.

It was an indication of the condition of the Liberal Republicans that they made Greeley their candidate for the presidency. They had done so reluctantly, having first approached Sherman, who had replaced Grant as the commanding general of the US Army. That was unwise, since Sherman bitterly detested politics and politicians, and replied: "What do you think I am, a damned fool?! Look at Grant! Look at Grant! What wouldn't he give now if he had never meddled in politics!" Greeley was very well known, of course, but as much of his notoriety was for his highly public and eccentric views. People might be amused by Horace Greeley but few took him seriously, and those who took him seriously often detested him.

Greeley was more given to theatrics than tact and pointlessly offended many people with his statements -- for example proclaiming that while not all Democrats were horse thieves, all horse thieves were Democrats. He got at least as good as he gave, with the campaign becoming very loud and nasty. Greeley said: "I was assailed so bitterly that I hardly knew whether I was running for the Presidency or the Penitentiary." He was soundly defeated, with 66 electoral votes to Grant's 286. Greeley, worn out, died a month later, aged 61.

* In an environment where deals meant much more than ideals, the goal of reforming Southern society and ensuring civil rights was gradually forgotten. Most of the Radicals were gone, survived in Congress by opportunists like Ben Butler, who found the gilded postwar environment perfectly satisfactory. Most Northerners, busy with a booming economy, only wanted to put the war behind them. Before the war, abolitionists had been able to influence a broader public -- but now slavery was officially dead, and as far as most folks were concerned, that was good enough. Although the Freedman's Bureau had obtained another extension in 1868, its functions were trimmed, and it was shut down at the end of June 1872.

While tens of thousands of Southern officials had been disenfranchised after the war, the North was tiring of vindictiveness. A General Amnesty Act was passed in 1872 that restored the full rights of all but a few hundred. In the meantime, the various armed and militant white supremacist groups in the South were busy undermining Republican rule through harassment and intimidation. Stories of murders and other atrocities filtered North, but the public had become indifferent.

In New Orleans, on 14 September 1874, 3,500 armed White League men attacked 3,600 police and black militia commanded by James Longstreet -- previously a Confederate general, one of Lee's most important lieutenants. The White League men scattered the defenders, capturing Longstreet. 38 men were killed and 79 wounded in the fight; the White League men were enraged at Longstreet, and it was only with difficulty that their leaders prevented them from shooting him. The White League ran the state government for three days, until US Army troops arrived and chased them back out.

Northern papers bitterly criticized Grant for sending in the army, calling him a tyrant. The North no longer had any enthusiasm for the use of force to keep the South in line. Even at the beginning of the Civil War, only the most extreme Northerners had wanted to change the social order of the South, with the real push towards conflict driven by the prospect of extension of slavery to the West. During the war, most Northern troops fought not to destroy slavery, but to preserve the Union. That goal had been achieved, and had also buried the question of the extension of slavery to the West that had led to the trouble in the first place.

The North's primary war goals having been achieved, Northern concern over how the Southern states did things, however disagreeable it might seem to outsiders, gradually faded out. Besides, there were many Northerners who were perfectly happy to see blacks kept in their place, and so just as happy with the reassertion of white supremacy in the South.

Grant refused to send in the troops again; the White Leagues and similar white-supremacist groups were able to do as they pleased. The Republican state governments began to fall, and by 1876 the only states that were still under Republican control were South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana. Some carpetbaggers assimilated, working agreeably with the new order; those who didn't get with the program were chased out, in a few cases murdered. Black people were put on the bottom of the social order.

In fact, in some ways slavery returned. States had set up programs to obtain revenue by farming out convict labor, and as the scheme began to be profitable, black people were often arrested on trivial pretexts and put to work in chains. Southern governments began to implement "Jim Crow" laws -- the name being derived from a pre-war black-face "minstrel show" character -- that were, in effect, lightly-disguised versions of the older Black Codes, intended to keep black people in their place, segregating them from mainstream white society and curtailing their voting rights.

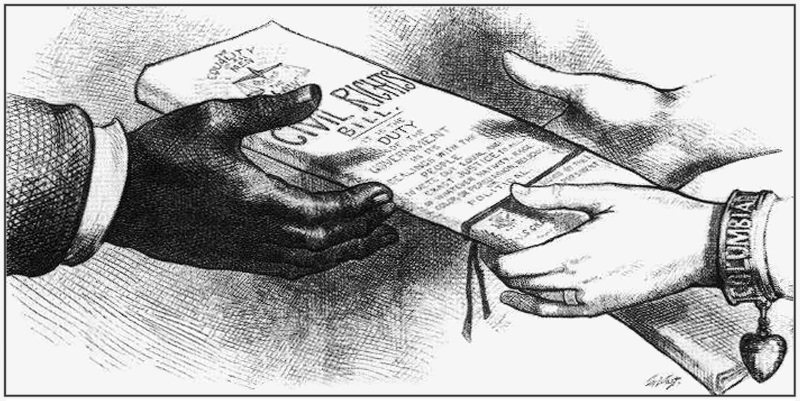

In a last-ditch effort to halt the rollback of social reform in the South, the US Congress had passed a "Civil Rights Act" in 1875, originally proposed by Sumner and Butler five years earlier, to ban discrimination in schools, places of public accommodation, transportation, and juries. It would prove ineffective.

* The Presidential election of 1876 was the last major act in Reconstruction. There was some consideration for Grant running once more, but although he retained his stature as one of the great heroes of the war, few retained any confidence in his political leadership, such as it was.

Grant's second term had led to as many or more scandals as the first. In 1873, the lingering effects of government war dept helped bring on a great financial panic that triggered a severe economic depression. The economy went back on the boom within a few years, but in the meantime widespread hardship helped increase dissatisfaction with the Grant Administration. As election time approached again, a contemporary political cartoon depicted Grant standing in front of a bar in Uncle Sam's Saloon, with Uncle Sam holding a bottle of OLD THIRD TERM. Grant asks: "How 'bout another?" Uncle Sam replies: "I think you've had enough."

The Republicans nominated Rutherford B. Hayes, who had a good war record, had been governor of Ohio for three terms, and wanted civil service reform. The Democrats nominated Samuel J. Tilden, a reformist governor of New York, and hoped to win thanks to popular disgust with the widespread corruption of the Grant Administration. The vote was very close, and the result was bitterly contested to the point where a new rebellion seemed possible. Grant publicly threatened to impose martial law if "warlike concentrations of men" arose.

The swing factor in the contest was the electoral votes of the three Southern states still in Republican hands. To break the impasse, prominent Republican and Democrat leaders went into extended negotiation sessions, and in the end Hayes became president. The Southern Democrats played a controlling role in the negotiations, and the Republicans offered them a better deal.

The agreement was known as the Compromise of 1877. Hayes quickly withdrew Federal troops from the South, though it appears that he had planned to do so anyway, and that the real concessions to the Southern Democrats were economic. However, the withdrawal of troops allowed the Southern Democrats to "declare victory" to their own people, a useful face-saving gesture after having backed a Republican nominee for the presidency. With the troops gone, the last Southern Republican state governments finally fell. Reconstruction was over.

The South had lost the war but had managed to win the peace, preserving much of their prewar social order. It was the sole consolation of defeat and a demotion of the South in national affairs relative to prewar days -- with the irony that the backwards social order retained by the South helped perpetuate that diminished influence.

BACK_TO_TOP* Jefferson Davis lived out a full life as a walking, unrepentant memorial of the Confederacy, observing with a stiff dignity the passing of the great figures of the war from North and South. Somewhat for lack of much else to do, he wrote his memoirs of the war, supported by a large inheritance from a wealthy and childless widow who had been one of his admirers. Davis was too proud to accept charity, but there was no way to refuse the gift under such terms.

The two-volume book, THE RISE AND FALL OF THE CONFEDERATE GOVERNMENT, was published in 1881. It traced the events to which Davis had been such a well-placed witness, unsurprisingly making the case that the South had a perfect right to secede from the Union, and that the Federal war against the Confederacy had been a crime. Davis would never admit that he had betrayed the Constitution, that he had by that document's provisions clearly committed treason, that he was only spared the noose by the generous spirit of reconciliation of the victors.

Nonetheless, he was wrong. The Constitution was never amended to deny secession -- because it had never allowed for it in the first place. For whatever satisfaction the book might have given him, it didn't make him much money, since the book was too expensive for most Southerners, and was of no interest to the North. However, it did nothing to diminish his prestige.

Although Davis was obstinate in his continued faith in the rightness -- if not the realism -- of the Confederate cause, and in his condemnation of the North's campaign against it, he was remarkably charitable to his enemies. Grant lost all of his money after leaving the White House, being caught up in a swindle, and then was diagnosed with throat cancer. With not long to live, he began work on his memoirs, which he hoped would support his wife after he died. Grant had been one of the most determined enemies of the Confederacy and his presidency was a disgrace, but Jefferson Davis saw fit to be kindly: "General Grant is dying. Instead of seeking to disturb the quiet of his closing hours, I would, if it were in my power, contribute to the peace of his mind and the comfort of his body."

Grant's term in the White House had been a sad business, but in his last months his iron determination came back to the surface. As his son said, he wrote with one hand, held off death with the other, and finished his book only days before his death in July 1885 at age 63. The book was a great success, earning almost a half million dollars for his family, a real fortune at the time. In Davis's last public address, delivered in 1887, he encouraged others to be conciliatory:

QUOTE:

The past is dead; let it bury its dead, its hopes, and its aspirations. Before you lies the future, a future full of golden promise, a future of expanding national glory, before which all the world shall stand amazed. Let me beseech you to lay aside all rancor, all bitter sectional feeling, and to take your places in the ranks of those who will bring about a consummation to be wished -- a reunited country.

END_QUOTE

There would indeed be a reconciliation, but it would be largely on Southern terms.

* Jefferson Davis died in Louisiana on 6 December 1889, at the age of 81. He was buried in New Orleans, though re-interred in Richmond in 1893 at the direction of his wife. The last of the dominating figures of the rebellion -- Lincoln, Lee, Grant, Davis -- was gone. Davis was, however, mistaken that the past was dead. The social revolution that the Radical Republicans had attempted to impose on the South proved incomplete.

The Civil Rights Act of 1875 had outlawed discrimination in public places, such as hotels, restaurants, theaters, and railroads; it was struck down by the Supreme Court in 1883 under the CIVIL RIGHTS CASES -- a set of five similar cases judged collectively. The High Court judged such segregation constitutional, on the basis that segregation involved no direct legal attack on the rights of black Americans, instead imposing an undue burden on businesses, denying them the right to deal with customers as they preferred to.

The vote in CIVIL RIGHTS CASES was 8:1. The sole dissenter was Justice John Marshall Harlan, who proclaimed the court had effectively gutted the 14th Amendment -- acidly commenting that, before the war, the court had been perfectly agreeable to granting considerable authority to Congress in hunting down fugitive slaves. As far as the right of businesses to discriminate went, Harlan pointed out that common law had long established that businesses such as hotels, restaurants, and theaters performed a public function, and that governments had appropriately regulated their operations to a degree. If businesses discriminated, they did it with the tacit approval of the state government, meaning the 14th Amendment was applicable. Harlan was ignored, but he wasn't forgotten.

The Supreme Court wasn't finished with endorsement of Jim Crow, either. In 1890, the state of Louisiana passed a law requiring segregation on trains. Ironically, the railroad companies were not happy about the law, since it meant pulling more passenger cars. In 1892, one Homer Plessy -- an "octaroon", only 1/8th black -- challenged the law, with the support of the railroad companies, by sitting in a whites-only car. Plessy was arrested and convicted by Judge John Howard Ferguson, with Plessy paying a $25 fine. Plessy filed a suit, PLESSY V. FERGUSON, on the basis of violation of his rights under the 14th Amendment, which made its way up to the Federal Supreme Court in 1896. The high court ruled against Plessy on a 7:1 vote.

The basis of the decision was the assertion that separation did not necessarily imply inequality. What harm did it do black people to have their own facilities, separate from those of whites? The problem was that facilities for blacks were consistently inferior to those of whites. The sole dissenter was, again, Justice Harlan, who eloquently commented:

QUOTE:

The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so it is in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth and in power. So, I doubt not, it will continue to be for all time if it remains true to its great heritage and holds fast to the principles of constitutional liberty.

But in view of the constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful. The law regards man as man, and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved.

It is therefore to be regretted that this high tribunal, the final expositor of the fundamental law of the land, has reached the conclusion that it is competent for a state to regulate the enjoyment by citizens of their civil rights solely upon the basis of race. In my opinion, the judgment this day rendered will, in time, prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal in the Dred Scott Case.

END_QUOTE

With judicial blessing, the Jim Crow society of the South crystallized, black folk being assigned second-class status in segregated transportation; public facilities; and government services, notably schools. Disenfranchisement of black people by tricks such as literacy tests, poll taxes, and arcane regulations whittled the black voter base down to nothing: in 1900, although Louisiana had a majority black population, only 5,320 black men could vote; by 1910, the number was only 730. While the 14th Amendment had declared that reductions in suffrage would be matched by reductions in representation, that provision wasn't enforced.

* The Jim Crow society of the South would stubbornly persist, only beginning to crumble in the 1950s -- with the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren finally taking the 14th Amendment seriously, and progressively dismantling the fraud of "separate but equal". The legal battle was largely completed by President Lyndon Baines Johnson, who pushed through the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which nationally banned segregation and bogus voter registration requirements, followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which went after voter disenfranchisement in detail.

The story of the modern struggle for civil rights is too elaborate to be told here, and in fact it's not completely over yet. Jim Crow did not simply vanish, of course; indeed, in the second decade of the 21st century its shadow was only too obvious in the struggle to remove memorials to the Confederacy -- in effect, memorials to Jim Crow -- from public places. Confederate apologists persist -- noisily claiming that the Civil War had nothing to with slavery; that large numbers of black folk fought as active combatants for the Confederacy; and even proposing with a straight face the fantasy that the South should take another shot at secession. Yes, after all, it worked so well the first time.

The reality is that the Confederacy was a wretched failure, and Jim Crow -- the lingering echo of the Confederacy -- was a monstrosity. Confederate apology is fading away; although some sympathy for the Confederacy lingered for a long time, even among those who recognize it as a bad cause, that sympathy is evaporating as well. The Confederate battle flag has become the banner of white supremacy in the 21st century, underlining that the Confederacy embodied the worst of the principles in the founding of the American Republic.

Abraham Lincoln, somewhat reluctantly, began a revolution. His election created, against his will, the Confederacy; to preserve the Union, the "last, best hope of earth", he crushed the rebellion and destroyed slavery. Jim Crow, the shade of the Confederacy, endured for almost a century following his death, to then obstinately cling in its fade-out to a past that has no claim over the present. The Confederacy has been discarded into the toxic waste dump of history, along with all the other dead-end regimes of the past. Those who fought for it, whatever their personal virtues, can be granted no real glory for their support of a bad cause.

BACK_TO_TOP* This document was derived from a history of the American Civil War that was originally released online in 2003, and updated to 2019. It was a very large document, and I first tried to simply break it into volumes for publication in ebook format; however, that proved unsatisfactory, and I decided to rewrite components of it to tell the story of famous battles and such. This stand-alone document was initially released in 2022.

Sources:

When I was interested in picky details, I'd scrounge the internet, particularly the Wikipedia, for leads.

* Illustrations credits:

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 jan 22 v1.0.1 / 01 jul 23 / Review & polish. v1.0.2 / 01 jul 25 / Review & polish.BACK_TO_TOP