* The American Civil War was fought over slavery -- though at the outset, Union leadership tiptoed envisioned that the nation could be restored to the status quo before the war, without any change to the slaveholding order. As the war progressed, it became obvious that was unrealistic, with gradual steps taken to end slavery once and for all. The issue of ending was coupled to the issue of what would happen with the breakaway states in the restored Union. At the end of the fighting, neither question had been resolved.

* On 12 April 1861, forces of the secessionist Confederate States of America opened fire on Fort Sumter, a Union outpost blocking the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. The next day, the garrison capitulated, formally surrendering on the 14th. That same day, Union President Abraham Lincoln called up militia from the loyal states to suppress the insurrection of the secessionist states. Southern states that had been sitting on the fence concerning secession immediately joined the Confederacy. The American Civil War had begun.

Tensions between the slave-holding and the free states had been growing for decades. It was the election of Republican President Abraham Lincoln that had tipped the South over to secession. Lincoln was the first American president to be clearly opposed to slavery; however, secession was a drastic measure in response, since Lincoln had repeatedly made it clear he would take no action to eliminate slavery from the states in which it existed. He was certainly opposed to the extension of slavery into the new territories in the West; he did want to end slavery completely in America, but he only contemplated buying slaves from their masters over a period of a generation or so. Even that seemed like a hard sell, and Lincoln had little expectation of living long enough to see the end of slavery in America.

At the outset of the conflict, the official policy of the Federal government was that the breakaway states would be brought back into the Union, with the status quo, including slavery, maintained. The problem was that, from the start of the conflict, runaway slaves crossed into Union-controlled territory to escape their masters. General Benjamin Butler -- a devious and unscrupulous Massachusetts politician, playing military officer under state commission -- ingeniously termed the escaped slaves "contraband of war", with the Union proclaiming the right to seize property, in this case slaves, of Southerners in rebellion against the Federal government.

On 6 August 1861, Congress passed a "First Confiscation Act" to endorse the scheme, with the "contrabands" effectively declared freemen. Lincoln felt the act went too far and was reluctant to sign, but he was persuaded by antislavery members of Congress to do so. In any case, slaves started coming over Union lines in increasing numbers. The Union set up "contraband camps" to care for them, hired them on as laborers, and eventually started to recruit them as soldiers.

The war was beginning to erode slavery, and in doing so eroded the idea that the states in rebellion could be brought back into the Union on the basis of the status quo ante bellum. All the Confederate states were slave states, indeed the Confederate constitution denied the right of a state to ban slavery; remove slavery, and the fundamental basis of Southern society would cease to exist.

Lincoln thought that slavery had to go eventually, but he didn't want to get rid of it in a revolutionary fashion, instead working towards compensated emancipation. On 6 March 1862, President Lincoln sent a special message to Congress, that read in part:

QUOTE:

Resolved, that the United States ought to co-operate with any state which may adopt gradual abolishment of slavery, giving to such state pecuniary aid, to be used by such state in its discretion to compensate for the inconveniences public and private produced by such change of system.

END_QUOTE

The resolution was duly passed through both houses of Congress on 10 April. On 16 April, the Federal government then followed up the resolution by abolishing slavery in Washington DC, buying up the roughly 3,100 slaves in the city, paying up to $300 each. It was a minor exercise, but it had major significance: the Federal government had demonstrated both the will and the ability to free slaves in territory under its control.

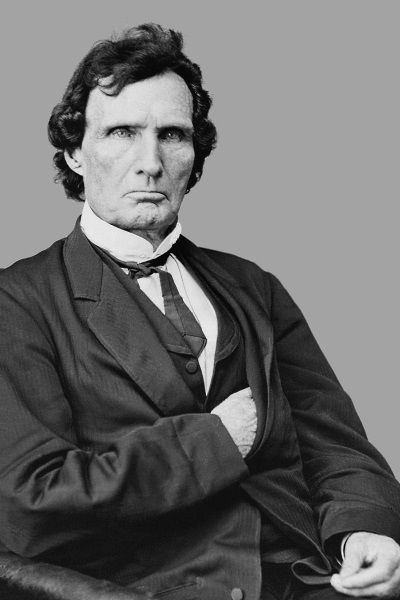

Nonetheless, compensated emancipation was, in hindsight, a non-starter. The leadership of the slave border states that had stayed with the Union regarded the idea with contempt, to the extent that they gave it any thought at all. The "Radical Republicans" in Congress, fiercely opposed to slavery and determined to make hard war on the South, were contemptuous. Congressman Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, the hardest of the hard-liners, called the measure "the most diluted, milk and water, gruel proposition that was ever given to the American nation."

* In the spring of 1862, there was cause for hope that the rebellion would soon be crushed. The fall of the city of New Orleans late in April seemed a particular blow to the Confederacy. However, in the summer of 1862, the Confederacy retook the initiative in the war, conducting offensives into Maryland and Kentucky that threw the Union on the defensive.

The change in fortunes of the war suggested to Union leadership that more drastic action was needed to suppress the rebellion. On 19 June, Congress abolished slavery in the Western territories without compensation. That was symbolic, since there were effectively no slaves in those territories; the exercise nonetheless indicated the way the winds were blowing. Lincoln dropped a hint to Congressional border state leadership in a message on 12 July:

QUOTE:

The incidents of the war can not be avoided. If the war continue long ... the institution [slavery] in your states will be extinguished by mere friction and abrasion ... It will be gone, and you will have nothing valuable in lieu of it.

END_QUOTE

They paid no attention. Lincoln had by that time realized that compensated emancipation was going nowhere, and also that undermining slavery profoundly undermined the Confederate war effort. On 13 July, he had a chat with Secretary of State William Seward and Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, Welles later recollecting:

QUOTE:

Further efforts with the border States would, he thought, be useless. That was not the road to lead us out of this difficulty. We wanted the army to strike more vigorous blows. The Administration must set the army an example, and strike at the heart of the rebellion. The country, he thought, was prepared for it.

The army would be with us ... If the rebels did not cease their war, they must take the consequences of war ... [Emancipation] was a military necessity, absolutely essential to the preservation of the Union. We must free the slaves or ourselves be subdued. The slaves were undeniably an element of strength to those who had their service, and we must decide whether that element should be for us or against us.

END_QUOTE

Congress continued the push against slavery, passing a "Second Confiscation Act" on 17 July, emancipating the slaves of Southerners in rebellion against the United States, and also passed a "Militia Act", which authorized the enlistment of "persons of African descent" into the Union Army. Lincoln was hesitant to sign the bill, questioning its constitutionality, but was persuaded to do.

Lincoln was not against what Congress was trying to do; he was just struggling to figure out a better way of doing it. On 22 July, Lincoln held a cabinet meeting to propose a general emancipation, without compensation, of all the slaves in the Confederacy. The consensus of the cabinet was that it was a good idea -- but needed to be put off until the Union's military situation improved, lest it seem an act of desperation.

The Confederate offensive into Maryland was halted in a blood-soaked battle at the town of Sharpsburg, on Antietam Creek, on 22 September; Confederate forces, overextended, would withdraw from Kentucky the next month. The day after the victory at Antietam, 23 September, the White House released a radical document: the Emancipation Proclamation.

It remains much misunderstood, described as: "Lincoln freed the slaves". That's only sort-of true. The document specified that it was issued under the authority of the Commander-in-Chief, with the sole objective of winning the war and restoring the Union. To that end, the Emancipation Proclamation declared:

QUOTE:

That on the third day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.

END_QUOTE

In short, all the slaves in the states in rebellion against the Union were declared free. This was done for no more stated rationale than to undermine the Confederate war effort, by depriving it of manpower -- and to increase Union manpower, the document encouraging the enlistment of ex-slaves into the army and navy. Lincoln had no authority to end slavery; but as Commander-in-Chief, he did have the authority to seize property of rebels, and dispose of it as the Federal government saw fit. It was arguably the most significant exercise of executive power in the history of the American presidency.

The document was strange in some ways. It said nothing critical of slavery, and didn't touch a single slave in any of the loyal slave-hold border states -- or for that matter, not even in occupied Louisiana. It only freed slaves in states where, at the time, the Union had no capability of enforcing the decree. The Emancipation Proclamation did encourage compensated emancipation in the border states, but did nothing to mandate it; and also made clear that if the states in rebellion came back to the fold by the end of 1862, they would keep their slaves.

Nonetheless, the simplistic message was true enough: Lincoln did free the slaves. By destroying slavery in its heartlands, he guaranteed the collapse of the entire wretched system. He also crushed any pretense that the Union would be restored as it was. He gave the Confederate states -- and, indirectly, the slaveholding border states -- a grace period to draw back from the precipice he had presented them, but with no expectation that they would do so. If they didn't, they would be responsible for, and suffer, the consequences.

In a letter to T.J. Barnett of the Interior Department during that interval, Lincoln wrote: "The character of the war will be changed. It will be one of subjugation and extermination ... The South is to be destroyed and replaced by new propositions and ideas." Exactly what sort of "new propositions and ideas" remained to be worked out.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Republicans suffered in the elections in the North that fall, but not enough to divert Union war policy. 3 January 1863 came and went, with no Confederate state indicating any desire to rejoin the Union -- indeed, the general tone in the South was belligerent rejection of the idea. On 13 January, Confederate President Jefferson Davis addressed the Confederate Congress, attacking the Emancipation Proclamation in detail, describing it as "a measure by which several millions of human beings of an inferior race, peaceful and contented laborers in their sphere, are doomed to extermination."

Davis went on to bitterly denounce the author of the document; suggest that captured Union officers be tried as slave-stealers, a capital offense; predict utter calamity for the Union as the result of the Proclamation; and declare that such an act of desperation underscored the weakness of the Federal war effort. Lincoln could only shrug; if Davis could not see the future, Lincoln could, and it was clearly a grim one for the South. During 1863, the Union regained the initiative on the battlefield, on 3 July driving back the last major Confederate offensive into the North at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and taking full control of the Mississippi River with the fall of the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi, the next day, effectively cutting the Confederacy in half. Confederate fortunes would, from that time, be on a gradual and fitful path of decline.

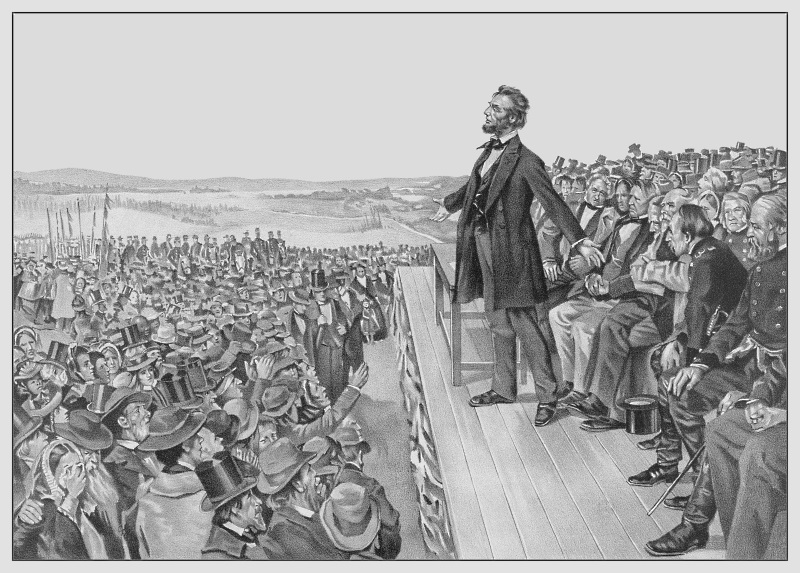

On 19 November 1863, on the occasion of the dedication of a military cemetery at Gettysburg, Lincoln delivered arguably the most famous speech in American history, which significantly concluded not only that the Union would endure, but that the era of slavery was over -- that "the nation, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth."

On 8 December 1863, Lincoln's annual "State of the Union" address was presented to Congress. Lincoln expressed his satisfaction with the progress of Union arms, which had led to revived public support for the war, with stronger support for Republican policy. Of course, Lincoln would have hardly been a politician had he not suggested that his Emancipation Proclamation had been a major factor in the successes of the Federal war effort:

QUOTE:

Of those who were slaves at the beginning of the rebellion, full one hundred thousand are now in United States military service, about one half of which actually bear arms in the ranks; thus giving the double advantage of taking so much labor from the insurgent cause, and supplying the places which otherwise must be filled with so many white men. So far as tested, it is difficult to say they are not as good soldiers as any.

END_QUOTE

Lincoln then listed other matters of administration, such as the budget; foreign relations; immigration; relations with the Indian tribes; and then moved on to the heart of the address, which concerned the processes by which the rebel states would be readmitted to the Union, contained in an appendix to his address titled: "A Proclamation Of Amnesty And Reconstruction".

The proclamation suggested that all rebels should be granted amnesty if they took an oath of loyalty to the US government, and proclaimed their support of the Emancipation Proclamation and all Federal laws on slavery. Senior Confederate government officials, military officers, turncoat US government officials, and those guilty of war crimes were to be denied amnesty. Once 10% of a state's citizenry, the number being determined by the 1860 census, took the oath, the state would be readmitted to the Union as if nothing had happened. The Federal government would repudiate all Confederate war debts.

It was not a strictly theoretical discussion. Lincoln had already written General Nathaniel Banks -- in charge of occupied Louisiana, like Ben Butler a Massachusetts politician in uniform -- suggesting that Louisiana might make a good place to perform an experiment along such lines. In the letter, Lincoln also made some necessarily vague but optimistic comments on the mechanisms of coexistence between white and black in the new post-slavery order.

Such Democrats as remained in Congress found the President's ideas radical and harsh. They believed that the Union should be restored with no change in the status quo as prevailed before the war. That was unrealistic given that the clashes of armies had already effectively destroyed the status quo, and the Democrats were a minority anyway. In contrast, the Radical Republicans in Congress didn't think the President's ideas were harsh enough. To them, the wayward states were to be treated like the military conquests they were, or soon would be. If the South were to be readmitted to the Union, it would be in a form acceptable to the Radical Republicans.

* Nonetheless, Nathaniel Banks pushed forward on Lincoln's "Ten Percent Plan", with a reconstructed Louisiana electing one Michael Hahn, an immigrant from Bavaria, governor of the state on 22 February 1864. Although Banks had banned slavery from Louisiana by decree, the new state constitution was ambiguous on the rights of free black people. The ambiguity was deliberate, Banks and Hahn having had to struggle very hard to prevent the state constitution from specifically stating that black men would not be given the right to vote. Still, it all seemed like a step in the right direction, and at the time a similar exercise was taking place in Arkansas, with a new state government -- which constitutionally banned slavery and secession -- in place before the end of March.

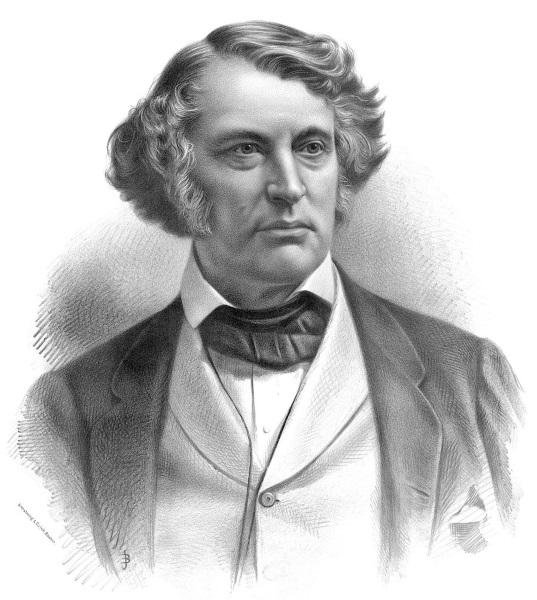

The Radical Republicans in Congress found the Ten Percent Plan too lenient, and were also determined to put paid to slavery once and for all. Their ideas congealed that spring in a bill promoted by the Senator Ben Wade of Ohio, one of the hottest of the Radicals, and his opposite number in the House of Representatives, the equally uncompromising Congressman Henry Winter Davis of Maryland. Their legislation raised the proportion of voters taking the loyalty oath to 50%; specified that military governors run the state until state conventions drafted a new constitution banning slavery, as well as repudiating secession and Confederate war debts; and gave amnesty only to those who could prove they hadn't willingly supported the rebellion.

The Wade-Davis bill passed both houses of Congress easily in May; the bill would come before Lincoln in early July, and he would refuse to sign it, saying it was an attempt by Congress to usurp executive powers. Besides, the bill was an attempt to address "a matter of too much importance to be swallowed in that way." -- the Radicals reacting with fury. Lincoln was in general agreement with the Radicals on the need to kill off slavery for good. The Emancipation Proclamation had been a huge step to that end, but it was an ad-hoc measure, dangerously flimsy from a legal point of view, and Lincoln knew it. All through 1864, a "13th Amendment" banning slavery had been working its way through Congress, the Senate having voted for it on 8 April 1864; it then went to the House, where it needed a two-thirds majority to then be sent out to the states for ratification.

On 15 June, the House failed to provide the necessary two-thirds vote. There matters stood for the time being, there being nothing more to be done until after elections in the fall. The elections would certainly be held, there being no provision in the Constitution permitting their suspension.

The war against the Confederacy was not going well at the time: a Union offensive in northern Virginia that began that spring -- with Union forces under General Ulysses S. Grant moving against Confederate forces under General Robert E. Lee -- had ground down into a ghastly war of attrition, with severe casualties on both sides. By late summer, the fighting in Virginia had settled into a stalemate, with trench warfare at the town of Petersburg, to the south of the Confederate capital of Richmond. The sitting war was not satisfactory to the Union cause, but Robert E. Lee's forces were finally pinned to the defensive, and the massive bloodletting of the spring offensive was over.

To the west, a drive through northern Georgia towards Atlanta by Union forces under General William T. Sherman, opposed by Confederate forces under General Joseph E. Johnston, was not making rapid progress. To be sure, the far-sighted could see that the war of attrition in northern Virginia favored the Union, which had more troops and resources, while Sherman was making fitful progress towards Atlanta. Nonetheless, it was anyone's guess as to which way the voters might go.

On 1 September, Atlanta fell to Sherman's forces; now few Northerners saw any reason to give up the fight. In the elections on 8 November, Lincoln was re-elected by an electoral landslide and a comfortable margin in the popular vote, giving him a mandate for prosecuting the war to its end.

* On 6 December 1864, Lincoln's State of the Union address was delivered to Congress by John Hay, one of the President's personal secretaries. The address attended to the mundane details of foreign and domestic affairs of government. It said little about the war itself, other than that it was going well for the Union, a fact obvious in both North and South. To drive home the fact that the Confederacy didn't have a future, Lincoln pointed out that the Union could "if need be, maintain the contest indefinitely."

Lincoln also mentioned the determination of the "insurgent leader" -- Jefferson Davis -- to continue the fight for Southern independence to the bitter end, Lincoln saying Davis had made it entirely clear that he would "accept nothing short of the severance of the Union, precisely what we will not and cannot give." That was a rebuke to those in the North who believed that the fighting would have ended had it not been for the failure of Union leadership to come to a reasonable agreement with the Confederacy.

The President was clearly saying that the Union would continue the war until the Southern states gave up their bid for independence -- though he softened the harshness of his language by adding that he would offer such "pardons and remissions of forfeiture" as were in his power to grant.

Lincoln also pushed for passage of the 13th Amendment. There were still plenty of Democrats in the House who might block its passage; they would be gone once the Republicans who had replaced them in the 1864 elections took their seats -- but Lincoln didn't want to wait, since banning slavery would help persuade the South to give up the fight more quickly. As long as the rebels felt there was a chance that continued resistance might allow them to cut a deal to preserve slavery in the reconstructed Union, they might try to hold out.

Slavery was doomed in any case, but a Constitutional amendment would dash any hopes they had left. Any Southerner who didn't realize the cause was lost by that time was delusional, and Lincoln wanted to do everything he could to deflate their delusions in hopes that they came to their senses. At the time, General Sherman's army -- having abandoned and burned Atlanta in mid-November -- was marching through Georgia to the sea, leaving a path of destruction behind them. The march made it clear that the Confederacy no longer was capabile of offering serious resistance to Union forces. The Federals reached the sea at Savannah, Georgia, on 21 December, to go into winter quarters.

In the meantime, the House of Representatives was debating the 13th Amendment, with the administration using all its powers of persuasion to encourage the representatives to vote YES. The House passed it on 31 January, the amendment then being sent to the states for ratification. To be adopted, the amendment had to be ratified by three-quarters of the states -- the problem there being that many states were still in rebellion against the Union. Most of the states in the North, and Louisiana, ratified the amendment over the following month; a few laggards remained in the North, while the Confederate states desperately fought on.

By the time of the House vote, Sherman's army had left Savannah, to advance north against scattershot Confederate opposition. The strategy was simple: Grant would maintain pressure against Lee's forces at Petersburg, keeping them pinned in place, until Sherman finally joined hands with Grant, to bag Lee's army. It was only a matter of time until the two Union forces met up. The Confederacy had no future.

There was public pressure in both South and North to negotiate an end to the conflict, but there was no basis for agreement: Jefferson Davis only wanted Southern independence, while Abraham Lincoln only wanted the restoration of the Union. Davis went through the motions of sending a "peace commission" to meet with Lincoln on 3 February -- but Lincoln made it clear to the commissioners that the fighting would end only when the South surrendered. The most he could promise them was that he would grant executive clemency to rebel officials when he could.

The commissioners went away empty-handed. Lincoln wanted to give the South a voice in how the Union would be restored, but Southerners refused to face the reality that, whether they liked it or not, the Union was going to be restored. The victors would determine how it was done.

BACK_TO_TOP* Sherman and Grant never did join hands. On 2 April, after growing pressure against Lee's forces at Petersburg, Grant's troops broke Confederate lines, rebel troops being put to flight. That day, Jefferson Davis and his cabinet fled Richmond, with the city falling to Union forces the next day. The day after that, Lincoln arrived in Richmond to inspect the conquered city.

On 10 April 1865, at Appomattox Court House in Virginia, Robert E. Lee surrendered the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia to Ulysses Grant, commander of the Union force. On 12 April 1865, after four years of war, the Army of Northern Virginia formally laid down its arms and dispersed. After four years of fighting, with hundreds of thousands of casualties and widespread destruction of the battleground states, the American Civil War was effectively over -- though there were many details to be tied up.

On 11 April, Lincoln gave a speech to the public from the window above the White House's front door, discussing the path forward. He began by praising the victories of Union forces, and then went on to discuss the restoration of the Union:

QUOTE:

By these recent successes the re-inauguration of the national authority -- reconstruction -- which has had a large share of thought from the first, is pressed much more closely upon our attention. It is fraught with great difficulty. Unlike a case of a war between independent nations, there is no authorized organ for us to treat with. No one man has authority to give up the rebellion for any other man. We simply must begin with, and mould from, disorganized and discordant elements. Nor is it a small additional embarrassment that we, the loyal people, differ among ourselves as to the mode, manner, and means of reconstruction.

END_QUOTE

Lincoln went on to conditionally defend, at awkward length, his Ten Percent plan for the reconstruction of Louisiana; to then suggest that the states of the South be welcomed back into the Union fold:

QUOTE:

We all agree that the seceded States, so called, are out of their proper relation with the Union; and that the sole object of the government, civil and military, in regard to those States is to again get them into that proper practical relation. I believe it is not only possible, but in fact, easier to do this, without deciding, or even considering, whether these States have ever been out of the Union, than with it.

Finding themselves safely at home, it would be utterly immaterial whether they had ever been abroad. Let us all join in doing the acts necessary to restoring the proper practical relations between these States and the Union; and each forever after, innocently indulge his own opinion whether, in doing the acts, he brought the States from without, into the Union, or only gave them proper assistance, they never having been out of it.

END_QUOTE

Lincoln admitted the reconstructed Louisiana government left something to be desired, one sore point being the small proportion of citizens that had taken the loyalty oath. The President added:

QUOTE:

It is also unsatisfactory to some that the elective franchise is not given to the colored man. I would myself prefer that it were now conferred on the very intelligent, and on those who serve our cause as soldiers.

END_QUOTE

Was obtaining the loyalty oath from only 10% of the population of Louisiana, Lincoln asked, satisfactory? The new Louisiana state government was clearly loyal to the Union, even having ratified the 13th Amendment. What purpose would there be in repudiating it?

QUOTE:

Now, if we reject, and spurn them, we do our utmost to disorganize and disperse them. We in effect say to the white men: "You are worthless, or worse -- we will neither help you, nor be helped by you." To the blacks we say: "This cup of liberty which these, your old masters, hold to your lips, we will dash from you, and leave you to the chances of gathering the spilled and scattered contents in some vague and undefined when, where, and how."

END_QUOTE

Louisiana's ratification of the 13th Amendment suggested other ex-Confederate states might well follow. Ratification by three-quarters of all the states in the restored Union would deny the possibility of its repudiation.

The address didn't go over well with the excited public on the White House lawn; they were looking for a celebration of the Union victory, not a consideration of the difficult path of winning the new-found peace. That path was, however, of necessity weighing heavily on Lincoln's mind.

* On the 14th, Lincoln held a cabinet meeting at mid-day, with General Grant in attendance. Among the items of discussion were what should be done with Confederate officials. Lincoln commented: "I hope there will be no persecution, no bloody work after the war is over. No one need expect me to take any part in hanging or killing these men, even the worst of them. Frighten them out of the country; open the gates; let down the bars." He made waving motions with his hands. "Shoo; scare them off; enough lives have been sacrificed."

The cabinet also discussed plans for the reconstruction of the South. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton had written up proposals at the request of the President, suggesting interim military governments in the conquered states until they could govern themselves again. Lincoln said: "We can't undertake to run state governments in all these southern states. Their people must do that, though I reckon that at first some of them may do it badly."

That evening, Lincoln and wife, with two guests, went to nearby Ford's Theater in Washington DC, to see the play OUR AMERICAN COUSIN. During the performance John Wilkes Booth, a prominent actor, broke into the presidential box and shot Abraham Lincoln in the back of the head. The President lingered for some hours, then died. Vice-President Andrew Johnson was sworn in as president in Lincoln's place.

Booth had led a band of accomplices who were swiftly rounded up; he was hunted down by Union soldiers and killed on 26 April. Lincoln was one of the final casualties of the conflict, the fighting sputtering out. General Joe Johnston surrendered his command in North Carolina to General Sherman, also on 26 April; on 4 May, Confederate General Richard Taylor surrendered Confederate forces in the western theater to Union General Edward Canby.

That was the effective end of the fighting, though Federal authority wouldn't be restored to all the ex-Confederate states for over a month. On 19 June, Union Major General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, to take command there -- with Granger nullifying the Confederate government there, and declaring the liberation of the slaves. 19 June would go down in history as the day when slavery ended in the USA, becoming known as "Juneteenth", and ultimately becoming a Federal holiday.

Jefferson Davis's deposed government, on the run, had broken up into groups and gone their separate ways; Union cavalry tracked down Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his party, capturing them on 10 May. Davis was thrown in prison and, for the time being, treated harshly by his captors.

A handful of other senior Confederate officials were also imprisoned. Booth's accomplices were railroaded through a military tribunal and quickly sentenced, with four later hanged, on 7 July. The execution of one, Mary Surratt, was a complete miscarriage of justice; Surratt had simply been in charge of the boarding house where Booth had lived and met with his accomplices, with no evidence that she had any idea of what they were up to. It was expected that Andrew Johnson would pardon Surratt, but he made no effort to do so.

There were no wide-scale reprisals against Confederate officials and officers. Although Andrew Johnson had been breathing fire and brimstone about vengeance -- and there were those among the Radical Republicans in Congress who talked the same, or worse -- Johnson proved much more considerate than he would with Mary Surratt. On 27 May 1865, he ordered the release of most rebel prisoners. Two days later, on 29 May, he issued a "Presidential Proclamation Of Amnesty", which stated that any ex-rebel who took an oath of loyalty to the United States would be fully pardoned and would have full property rights, except for slaves.

The proclamation did have a long list of exceptions, but it went on to state that those on the list of exceptions could apply to the president for pardon, which would be "liberally extended". This statement was deeply suspected by those affected, considering Johnson's hot rhetoric and the kangaroo court that was trying Booth's accomplices. Much to the surprise of most, Johnson was as good as his word -- though as discussed later, there was an ulterior motive in his generosity.

The Radicals in Congress, notably Thaddeus Stevens in the House and Charles Sumner of Massachusetts in the Senate, had uncompromisingly pushed for hard war on the Confederacy, their goal being to absolutely crush the slave power once and for all. They called for hanging Davis, Robert E. Lee, and other prominent rebels, but the public had no stomach for such savageries. There had been more than enough killing and cruelty. Johnson granted pardons almost on request.

Taking the loyalty oath became much more acceptable when Robert E. Lee, the Confederacy's greatest hero, took the oath himself and encouraged others to do so. Lee had felt misgivings about secession before the fighting broke out, and in the end admitted that he had expected failure. Although Jefferson Davis had called for continuation of the war in the face of Union victory through guerrilla operations, Lee regarded guerrillas as no better than bandits, and made clear his disapproval of the idea; he wanted reconciliation with the Union.

Fortunately, Lee proved more influential than Davis. Henry Wise, previously a governor of Virginia and a Confederate general, was furious when one of his sons took the loyalty oath: "You have disgraced the family, sir!" His son replied: "But Father, General Lee advised me to do it." Wise, startled, thought that over for a moment, and then answered: "That alters the case. Whatever General Lee advises is right."

Lee was left to live in peace -- becoming president of Washington College, a small Virginia institution, dying in 1870. His estate at Arlington, Virginia, having been seized by the Union, had from 1864 become Arlington National Cemetery. Lee himself was not granted a pardon in his lifetime, though he would be politically rehabilitated in 1975, over a century later, by an act of Congress.

One other Confederate officer was not as fortunate. Henry Wirz was the Swiss-born commandant of the Confederate prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia, where 12,000 Union prisoners died. News of the miserable conditions in the camp had enraged the North. The fact that the Confederacy simply lacked the resources to take care of so many men when their own armies lacked food and clothing wasn't considered -- nor was the fact that Northern prison camps also suffered from disease and maltreatment. Wirz was put through a military tribunal similar in flavor to that which had tried Booth's accomplices, and condemned to death. He was hanged on 10 November 1865, then buried next to Booth's accomplices.

However, by that time most Confederate government officials were free men, with the few left freed through 1866 -- though Jefferson Davis remained in custody for another year after that. Talk of putting him on trial never went beyond talk. Davis was too prominent, such a trial would be too visible to the public, while every outrage against justice would be splashed up and dissected in newspaper headlines.

One of his strongest advocates was Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Salmon Chase. Justice Chase felt there was no clear-cut legal case against Davis for having been the president of the Confederacy, and wisely added: "Lincoln wanted Jefferson Davis to escape, and he was right. His capture was a mistake. His trial will be a greater one. We cannot convict him of treason. Secession is settled. Let it stay settled."

The American Civil War was bloody and brutal, but unusual in some respects. A reading of history doesn't give much basis for expecting that the captured leader of a rebellion would not merely escape execution, but would even be allowed to walk free and pursue his private life. Davis never did ask for a pardon -- even when the Mississippi legislature asked him to, so they could send him back to the US Senate. He lived instead on the honor of being the President of the Confederate States of America, revered in the South in a way that he had never been when the title actually carried authority, not merely the nostalgia of a long-lost cause.

There was never any serious doubt that the cause had been lost. Most of the rebels had all they wanted of war, and no thought of reviving the struggle. Living conditions were harsh, and most ex-Confederate soldiers had no greater thought than to get back to their homes and take care of their families. In fact, although many Southerners would take lifelong pride in their struggle for independence, there was at least a thought in hindsight that maybe secession hadn't been all that good an idea; a warm remembrance of the proud Confederate battle flag didn't really equate to an equally fond memory of the half-baked Confederate state.

Not long after the end of the war, Joe Johnston was on a steamer when he overheard a young man proclaim that the South had been "conquered but not subdued." Johnston asked the young man whose command he had served under, and the young man replied that he had not been in the army. Johnston then said: "Well, sir, I was. You may not be subdued, but I am."

BACK_TO_TOP