* The Confederate invasion of Kentucky soon ran out of steam, with rebel forces dangling precariously at the end of a long supply line, confronted by large and intact Union forces. Braxton Bragg was forced to withdraw, with Buell cautiously pursuing him, leading to an inconclusive battle at Perryville. Bragg was still able to take his troops safely to his base at Murfreesboro, Tennessee; Buell was sacked for his lack of drive, being replaced by General William Rosecrans. Unfortunately for the Union, it didn't seem like Rosecrans was in any hurry either.

* While Braxton Bragg's offensive pushed into Kentucky, in the meantime Edmund Kirby Smith, from his roost in Lexington, had been sending out detachments of troops and cavalry in all directions to keep the Federals off balance. They had been doing a great job of it, and both Louisville and Cincinnati were in a panic.

William Nelson, recovering from his wounds, was in Louisville, trying to organize a defense with another set of raw recruits only too painfully like those who had run away from Smith's men. Lew Wallace had been summoned to Cincinnati to direct the defense of that city. He declared martial law and impressed citizens into service to help beef up the city's defenses. Thousands of backwoodsy Unionists showed up in the city with squirrel rifles with the expectation of bagging Confederates, and the local press made much of the heroic "Squirrel Hunters". A "Black Brigade" was also organized from the black citizens of the city, though it was strictly a labor organization; the men were not armed, and the brigade was only for the duration of the emergency.

George Morgan, down in the Cumberland Gap, finally decided that he was too isolated and withdrew on 17 September, doing a thorough job of torching everything that might be of use to the rebels. He and his men made a 200 mile (320 kilometer) forced march across the barrens to the Ohio River, with the rebels in futile pursuit.

Having the Yankees on the run was gratifying to the Confederates, but Smith was really not a serious threat by himself. His men were spread too thin to overrun any position held in force, though few Yankees realized it at the time. However, the Federal leadership realized that if Braxton Bragg moved north to link up with Smith, the rebels would become a much bigger threat. The strange thing is that the rebels didn't seem to understand that at all. Braxton Bragg had been determined to drive on to Louisville, but while the affair at Munfordville had delayed him two days, he seemed in no hurry once that obstacle was removed. Smith, on his part, seemed totally disinterested in any cooperation with Bragg.

On the other side, Buell was suffering some indecision of his own. After arriving in Bowling Green, he had sent for George Thomas to join him with two of the three divisions left behind in Nashville. The threat posed by Bragg's army seemed substantial enough to commit almost everything he had. Buell moved forward towards Munfordville on 18 September, with every expectation of doing battle with Bragg, who certainly would be expected to block Buell's line of advance to Louisville. However, after some maneuvering along the Green River, Bragg pulled out and withdrew to the north, toward the town of Bardstown, where he expected to link up with Smith. Bragg had lost his nerve, later reporting to Richmond that he had been concerned about supplies.

Buell followed on 20 September when Thomas arrived with his two divisions. Much to Buell's surprise, Bragg was gone, and as the Federals moved cautiously up the road to Louisville, they discovered that Bragg had left nothing to resist them in their path. Advance units of Buell's army marched into Louisville on 24 September, with Buell himself following the next day and the rest of the army trailing behind. William Nelson was relieved, wiring Cincinnati:

LOUISVILLE IS NOW SAFE. WE CAN DESTROY BRAGG WITH WHATEVER FORCE HE MAY BRING AGAINST US. GOD AND LIBERTY.

Bragg understood he was at risk, reporting the news to Richmond that same day, 25 September, and complaining bitterly about the failure of Kentuckians to rally to the Confederate cause: "General Smith has secured about a brigade -- not half our losses by casualties by different kinds." Bragg had been counting on Morgan's reports that tens of thousands of Kentuckians would join his ranks, but, as Smith had reported to him the week before: "Their hearts are evidently with us, but their blue-grass and fat cattle are against us."

Secession had been a popular idea at the beginning of the war because many refused to believe the Federal government would do much about it. That view of matters had been proven thoroughly, fearsomely wrong. With Buell and a large army of Federals at large, the Kentuckians stood to lose everything if Confederates marched off and left them at the mercy of the Union army. It was a no-win game: Bragg could not get local reinforcements unless he crushed Buell, and he could not crush Buell unless he got local reinforcements. Bragg railed at the "cowardice" of the Kentuckians, failing to see that he was asking them to stake their lives and property on a wild leap into the unknown.

The odd impasse between Bragg and Smith continued as well, with Bragg in Bardstown asking for help from Smith to assist him in a drive on Louisville -- while Smith up in Lexington, about 50 miles (80 kilometers) away, encouraged Bragg to do it himself. For want of anything better to do, both men scrounged up supplies from the rich countryside.

Militarily, the rebel offensive was going nowhere. Bragg instead concentrated on a publicity stunt. A provisional Confederate Kentucky government had been established in November 1861, but had been forced to flee south after the fall of Fort Donelson, and the provisional governor had been killed in action at Shiloh. Bragg intended to inaugurate the current Confederate provisional governor-in-exile of Kentucky, Richard Hawes, in a formal ceremony in Louisville to establish Kentucky as a de facto Confederate state. Bragg spent the last days of the month of September working on this scheme.

* As for Don Carlos Buell, he had been proving that somehow he and Braxton Bragg deserved each other. A reporter on the march to Louisville noted the man's shabbiness and taciturn nature: "Buell is, certainly, the most reserved, distant, and unsociable of all the generals in the army. He never has a word of cheer for his men or his officers, and in turn his subordinates care little for him save to obey his orders, as machinery works in response to the bidding of the mechanic."

Buell seemed to have dragged a black cloud with him to Louisville, immediately getting into a squabble over jurisdiction with the commander of the local military district, General H.G. Wright, that was only resolved in Buell's favor after an exchanged of telegrams with Halleck. Buell's jinx went much deeper than that, and came to full black bloom on 29 September. Among William Nelson's officers was a brigadier general with the unlikely name of Jefferson C. Davis; he was thin-skinned, Nelson tended to bully, and the two men clashed. Nelson finally had ordered Davis to get out of his department the week before.

Davis, who was an officer of Indiana volunteers, came back that morning with serious reinforcements in the shape of Indiana governor Oliver Hazard Perry Morton -- a man every bit as obstinate as Nelson and carrying a few gripes of his own with the general. They confronted Nelson in the lobby of the hotel Buell used for headquarters, and an angry argument followed. Nelson called Davis an "insolent puppy", Davis retaliated by throwing a wadded-up calling card in Nelson's face -- and Nelson backhanded Davis.

Nelson asked Morton if he had come to insult him. Morton said he had not, and Nelson went up the stairs to Buell's room on the second floor, angrily speaking to a passer-by going down the stairs: "Did you head that damned insolent scoundrel insult me, sir?! I suppose he don't know me, sir! I'll teach him a lesson, sir!"

Meanwhile, Davis wandered around the lobby asking to borrow a gun; he found a captain who loaned him a revolver. Davis ran up the stairs after Nelson and found him at Buell's door. When Nelson approached him, Davis cried: "Not a step farther!" -- and shot the big man in the chest. Nelson turned around and tried to walk off, but fell to the floor. Men gathered around Nelson, who said: "Send for a clergyman. I wish to be baptized." They managed to carry his huge frame into a nearby room and rest him on a bed, with the wounded general saying: "I have been basely murdered." He died about a half hour later. He was 38 years old.

Buell had lost one of his best officers over an idiot quarrel. He had General Davis placed under arrest on charges of murder. And then lightning struck twice that morning: Buell was informed by courier that he was relieved of command and that George Thomas would take his place. Halleck had dispatched one of his aides, a colonel, on 24 September to give Buell the message, at the President's request. Lincoln indeed felt, as many of the general's officers did, that Buell would no longer do. The colonel had been told to not deliver the order if Buell had fought, or were to fight, a battle. When, three days later, Halleck learned that Buell had reached Louisville, he wired the colonel:

AWAIT FURTHER ORDERS BEFORE ACTING.

The colonel apparently never saw the message, for he wired Halleck at noon on 29 September:

THE DISPATCHES ARE DELIVERED. I THINK IT IS FORTUNATE I OBEYED INSTRUCTIONS. MUCH DISSATISFACTION WITH GENERAL BUELL.

A telegram from Buell himself arrived shortly afterwards, acknowledging the order and indicating that he would leave for Indianapolis. Three congressmen and a senator from the region immediately protested, for Buell was something of a hero in the region. Halleck found himself in a bind. George Thomas managed to break the impasse with a message of his own, declining command:

GENERAL BUELL'S PREPARATIONS HAVE BEEN COMPLETED TO MOVE AGAINST THE ENEMY, AND I THEREFORE RESPECTFULLY ASK THAT HE BE RETAINED IN COMMAND. MY POSITION IS VERY EMBARRASSING.

Halleck replied:

YOU MAY CONSIDER THE ORDER AS SUSPENDED UNTIL I CAN LAY YOUR DISPATCH BEFORE THE GOVERNMENT AND GET INSTRUCTIONS.

The dismissal was then suspended "by order of the President." Granted a stay of execution, Buell replied on 30 September:

OUT OF A SENSE OF PUBLIC DUTY I SHALL CONTINUE TO DISCHARGE THE DUTIES OF MY COMMAND TO THE BEST OF MY ABILITY UNTIL OTHERWISE ORDERED.

By that time, he had organized an army of over 75,000 men in ten divisions, and on 1 October 1862, he set off in pursuit of the Confederates. Incidentally, Davis would never be put on trial or punished for killing Nelson, the matter being lost in the shufflings of war.

BACK_TO_TOP* The large size of Buell's force was misleading, and he knew it. Many of the troops barely knew one end of a rifle from another, and none of his three corps commanders -- Thomas Leonidas Crittenden, James McCook, and Charles Gilbert -- had real qualifications for their rank. Thomas L. Crittenden, a cousin of the disgraced Thomas T. Crittenden, was enthusiastic, but hardly more than a country lawyer in uniform; McCook was only 31, something of a smartass, an "overgrown schoolboy" according to a reporter; and Gilbert was just a regular army captain who happened to be in Louisville when the present emergency began, to be abruptly promoted to a brevet major general. Buell had George Thomas, an entirely sensible man, as his executive officer -- but true to form Buell paid Thomas no mind, and Thomas was too easy-going to assert himself. Although the Federals substantially outnumbered the Confederates, Smith and Bragg's men were well-drilled veterans.

In any case, Buell directed his three corps southeast towards Bragg's army, which was arrayed around Bardstown, about 40 miles (64 kilometers) away. Buell sent two divisions, including one very big division of very green troops, under Brigadier General Joshua Sill directly east towards Frankfort, about 50 miles (80 kilometers) away, as a feint.

The rebels had problems of their own, mostly in the form of Braxton Bragg, who was at the moment not even with his army. He was still toying with the inaugural ceremony he planned for 4 October. Most of his cavalry was away: Forrest was recruiting in middle Tennessee, and John Hunt Morgan was pursuing George Morgan north across the Kentucky barrens. Bragg still got wind of the advance of Sill's divisions towards him in Frankfort on 2 October; he jumped at the bait, sending an order to General Polk down by Bardstown to move north and strike the Federals in the flank while Smith, whose forces were to move from Lexington to Frankfort, struck them from the front.

Polk, meanwhile, simultaneously sent couriers to Bragg to inform him of the three Yankee columns that were bearing down on Bardstown. When Polk finally got Bragg's orders to strike north, he replied on the next day, 3 October, that the conditions made "compliance with the order not only eminently inexpedient but impractical." He proposed to fall back that evening. Bragg agreed, instructing him the next day, the 4th, asserting that movement was "not a retreat, but a concentration for a fight. We can and must defeat them." And later added: "We shall put our governor in power and then seek the enemy."

The inauguration ceremony was under way even as he wrote, around noon on 4 October, but while Hawes recited his inaugural address the Federals began tossing shells into Frankfort. Bragg ordered his forces there to withdraw and burn bridges behind them; Hawes' return from government-in-exile proved very brief. On that same day, Polk and Hardee abandoned Bardstown, falling back to the southeast. Smith was moving south from Frankfort, trying at last to link up with Bragg's divisions. An onlooker observing Bragg's men marching past described the Confederates as "distressed, weary and harassed."

The Yankees followed in their four columns. Sill's two divisions were marching south, their feint having served its purpose, to link up with the rest of the army. The columns were very loosely coordinated and probed uncertainly for contact, but only encountered rebel cavalry that melted from sight. They were also desperately searching for water, for the long hot summer had dried up almost all the streams and lakes and there was little water to be found. Such as was available wasn't the best. A fellow in an Ohio regiment reported: "The boys got some water out of a dark pond one night and used it at supper to make their coffee and to quench their thirst also. What was their disgust next morning to find a dead mule or two in the pond. I imagine that coffee had a rich flavor."

The Confederates were moving towards the town of Harrodsburg, roughly at the southeast corner of a triangle formed with Frankfort to the north and Bardstown to the west. Bragg wanted to concentrate his men there to hit the Yankees, though he was still under the delusion that Sill's column was the real Federal striking force and the other columns were feints, a perception completely opposite to the truth. This fundamental confusion caused Bragg to scatter his divisions over the area, leaving them vulnerable to destruction in detail.

The Federals in turn were moving towards the town of Perryville, about 10 miles (16 kilometers) southwest of Harrodsburg, where Buell hoped to concentrate his own forces for a stand-up fight and obtain much-needed water. Gilbert's column reached the outskirts of Perryville on the evening of the 7 October, where they made contact with one of Bragg's scattered units and got into a small fight over access to a stream. The Federals were bloodied and had to pull back. That was not getting off to a good start, and with his typical bad luck Buell was in an ambulance at the time, having taken a nasty fall off a high-strung horse that afternoon. Buell was still as excited as he ever got, since he thought he had actually made contact with all of Bragg's army. He sent messages to the other columns that night to advance with all speed.

While Buell was preparing to attack the Confederates, thinking there were many more of them than were actually present, the Confederates were preparing to attack him, under the opposite impression that there were far fewer Yankees than were really there. That was due to Bragg's continued belief that the Union forces that had been pursuing Hardee and Polk were little more than diversions. He sent orders to the two generals to "give the enemy battle immediately." Hardee would strike with two divisions, while Polk would send in one, marching his other northward towards Harrodsburg.

Hardee got the orders after dark that evening. Though he approved of striking back, he was appalled that it would be done with Bragg's forces in such a scattered state. He immediately wrote a letter to Bragg recommending greater concentration of forces before taking action.

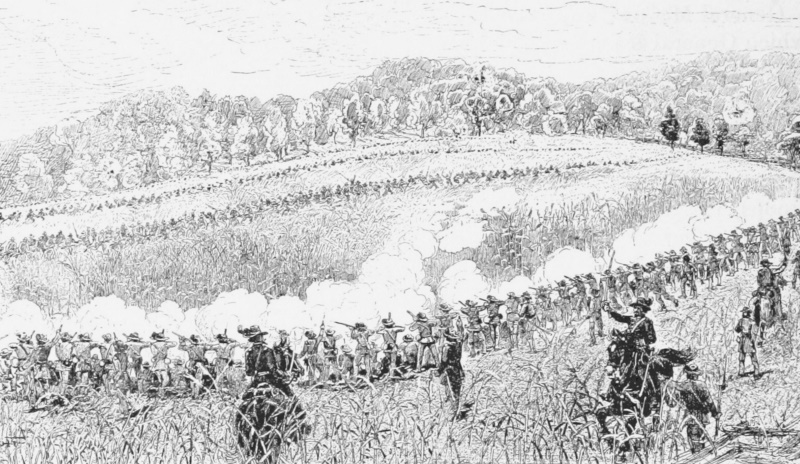

* Perryville was a small town straddling the Chaplin River. A stream named Doctor's Creek flowed into the river north of town, running down from heights to the south. It was along Doctor's Creek that initial collision took place. Gilbert's corps was directly west of Perryville, and just before dawn -- it was 8 October 1862 -- a brigade under Brigadier General Philip H. Sheridan moved east, shoved the rebels out, and seized the precious water as well as the heights beyond it.

Sheridan had only been a general for two weeks. He was a short, stocky, round-headed, 31-year-old Irishman, tough and aggressive, with a strong dislike of Southerners and their aristocratic pretensions. Sheridan went forward with such enthusiasm that Gilbert signaled him not to bring on a general engagement. Sheridan replied that the enemy had been preparing to attack him, and he wanted to hit first. The Confederates counterattacked, but Sheridan brought up the other brigades of his division and held his ground. The counterattack fizzled out.

The field remained quiet for the rest of the morning while McCook's men filed into line north of Gilbert's position, and Crittenden's men moved in to the south. By early afternoon, there were 55,000 Yankees lined up, ready to move forward. Buell was uncertain of rebel strength, but his intelligence indicated there were two divisions present. There were, as noted, actually three, consisting of two under Hardee and one under Polk. Bragg himself rode up at about 10:00 AM and asked why they hadn't attacked as ordered. Polk replied that he suspected he was facing all of Buell's army, but had been observing their activity at the north end of the line and would strike them if there was an opportunity. In reply, Bragg demanded that Polk attack.

Polk began massing two divisions in the woods. One division was under Simon Bolivar Buckner, and the other was under Benjamin Franklin Cheatham. At 1:00 PM, after an hour of bombardment, they went forward, supported by ranks of artillery. Cheatham sent his men forward with a cry: "Give 'em hell, boys!" Polk -- who, though a West Pointer, had been the Episcopal bishop of Louisiana before the war -- added a little more circumspectly: "Give it to 'em, boys! Give 'em what General Cheatham says!"

McCook's men were just moving into position and were unprepared. The rebels fell hard on McCook's lead division, under the command of Brigadier General James S. Jackson, and particularly on Jackson's foremost brigade, under Brigadier General William Terrill, a Unionist Virginian. Jackson was killed almost at the outset. The Federals buckled and fell back, then broke when Terrill was horribly wounded by a shell. The Confederates pursued, but as they encountered other divisions of McCook's command, they found the going increasingly rough and their progress slowed.

The rebels were attacking an army three times their own size; by all logic, once the Yankees got organized to counterattack the Confederates would be in serious trouble. In practice, the Federals failed to exploit their overwhelming advantage. While McCook asked for help from Gilbert and his corps to the south, Gilbert failed to respond decisively. Two brigades under Brigadier General Patton Anderson had attacked Sheridan and been driven back. Gilbert assumed this was the prelude to a full-scale attack and did not want to move out of position. Sheridan was far out on the front lines and at least could support Gilbert with artillery. His guns fired up the ranks of the attacking Confederates and did much to confuse them and slow their advance further. Gilbert, seeing the rebels falter, detached two brigades to help McCook, and then Sheridan advanced on Anderson and drove him back to Perryville, where the Confederates and Federals engaged in an artillery duel over the roofs of the town while the terrified citizens huddled in their cellars.

Further to the south, Crittenden didn't get into the fight at all, having been alarmed by Confederate cavalry feints. There was actually more to the odd lack of mutual support between the three Union corps than simple timidity: for whatever reasons sounds weren't carrying over the battlefield and, except to those directly engaged, there was little evidence that any fighting was even going on. Buell had no idea there was a battle under way until 4:00 PM.

By that time, the fight had bogged down into a confused brawl, with friends and foes intermingled, and soldiers firing on their own. One of Gilbert's brigade commanders went up to General Polk and said: "I have come to your assistance with my brigade!" -- and Polk, on finding out that the brigade in question wore Union blue, replied: "I believe there must be some mistake. You are my prisoner." The brigade itself escaped capture, to carry on the fight without their unlucky leader.

By the time the sun went down two hours later, the Confederate advance had ceased and the fighting began to die down, though the confusion persisted, aggravated by the fading light. Polk observed a unit firing into the flank of one of his brigades and galloped over to it by himself in excitement to tell the colonel in charge to cease firing on friends. The colonel replied in surprise: "I don't think there can be any mistake about it. I am sure they are the enemy."

"Enemy!. Why, sir, I have just left them myself! Cease firing, sir! What is your name, sir?!"

"Colonel Shyrock, of the 87th Indiana. And pray, sir, who are you?" If Polk had been amused at the confused Yankee officer earlier in the day, he now had an opportunity to see how funny the joke was when it was on him. He managed to keep his head, shaking his fist in the colonel's face: "I'll soon show you who I am, sir! Cease firing, sir, at once!" He then turned his horse around and ordered the Federals to stop firing, then rode deliberately back to his own lines, expected a bullet between his shoulders all the while.

There was a bright moon up that night; many of Buell's officers wanted to continue the fight past sundown, but the Federals couldn't shake off their confusion. By the time they got organized the next day, the rebels were gone. Bragg had finally realized that he was facing most of Buell's army, and at midnight ordered the divisions around Perryville to withdraw back to Harrodsburg. The Federals lost about 4,200 men, the Confederates about 3,300, but comparing numbers meant little. The battle had been confused and inconclusive, and if the Yankees lost more men, they had many more of them to lose. As a Confederate private, Sam Watkins of the First Tennessee, put it: "Both sides claiming the victory, both whipped." Watkins, who would fight in many of the major battles of the West, would often prove as much or more astute judge of events than the generals.

General William Terrill had died during the night while Bragg's men stole away. Terrill's decision to stay with the Union had infuriated his father. His only brother James decided to fight for the Confederacy under Robert E. Lee, and would be killed in turn. The family would raise a memorial to them, on which was inscribed: GOD ALONE KNOWS WHICH WAS RIGHT.

* The fight over, Bragg's divisions fell back in the rain. The drought had ended. Some thought the firing of the cannons had something to do with it. The rebels finally managed to achieve the concentration at Harrodsburg that Bragg had been seeking. There Bishop-General Polk conducted church services in the local Episcopal church, and wept with released tension from the fight the day before.

The morning after that Smith arrived, and a few hours later Buell's Federals moved into position outside the town. It seemed that the two armies were now going to have it out once and for all. Smith pleaded with Bragg: "For God's sake, General, let us fight Buell here." Bragg replied: "I will do it, sir." However, Bragg had been waffling for several weeks, and his insecurity was only increased by the news of rebel defeats elsewhere -- notably the lopsided defeat on 4 October of Confederal troops under Earl Van Dorn in an assault on Corinth by defending Union soldiers under Major General William S. Rosecrans. That night Bragg ordered his forces to withdraw, much to the anger of Smith, Hardee, and Polk.

When the sun came up, Buell found Harrodsburg deserted. He advanced cautiously into the town, suspecting a trap. Everyone had been expecting to fight and the rebels' departure didn't feel like it was supposed to be in the script. The two armies subsequently went through this odd dance of touchy approach and withdrawal a second time, and then on 13 October, Bragg made up his mind to pull out completely, marching his men back towards the Cumberland Gap in two columns. It was, an observer remarked, "a dismal but picturesque affair", with large herds of livestock driven down the road of retreat by cowboys pulled from Texas regiments, and a long train of heavily-laden wagons ranging from stagecoaches to 400 new Union army wagons that had been captured from Nelson at Richmond.

For a time, the rebels were harassed by Buell's cautious attacks at the rear of their columns, blunted by active Confederate cavalry, as well as mud and hard rains. On 16 October Buell broke off his pursuit, such as it was, and sent his army on the march towards Nashville. The Confederates had no further immediate worries from the Yankees, but they were very worn down by deprivation and exposure. Thousands would be on the sick list the time they returned to eastern Tennessee, a little less than a week later. They were deeply demoralized, with resentment against Bragg expressed by everyone from Smith, Polk, and Hardee down to the lowest private. A surgeon summed up the general feeling when he wrote that Bragg was "either stark raving mad or utterly incompetent."

The Southern newspapers lit into Bragg as well. On 23 October, he was summoned to Richmond by Jefferson Davis with a message:

THE PRESIDENT DESIRES THAT YOU WASTE NO TIME IN COMING HERE.

Jefferson Davis was a friend to Bragg, and Davis was loyal to his friends; indeed, Davis regarded many of the attacks on Bragg as simply indirect attacks on himself. However, Davis was still very much concerned by the criticisms made by Bragg's senior officers, and wanted to get the other side of the story. Bragg walked lightly in his discussions with Davis, pointing out the difficult circumstances of his army -- made worse by the failure of Kentuckians to come to his aid, over which he was still very bitter.

Bragg argued, with much basis in fact, that his military adventure was in many ways a success. He had inflicted 25,000 casualties on the Federals and captured immense quantities of weapons, ammunition, supplies, and equipment. He had penetrated deep into Union-held territory and thrown the Yankees on the defensive. Most importantly, he had removed Union pressure on Chattanooga and the lands beyond it to the south and east. The offensive had really amounted to nothing but a very big raid, but the refusal of Kentuckians to rise up in support of the invaders meant it couldn't have been anything else: had Bragg attempted to hold Kentucky, the Federals would have assembled far superior forces and simply wiped him out. By all sensible measures, Bragg's operation had been the most successful of all three of the fall offensives staged by the Confederacy.

Bragg had plans for the future as well. He wanted to move his army to Murfreesboro, and then liberate Nashville from the Federals. Davis was reassured, sent Bragg back to Tennessee, called Smith and Polk to Richmond in their turn, promoted them both to lieutenant general, and managed to persuade them to return to duty. That was a remarkable exercise in diplomacy for the sharp-edged Davis, but then the two generals were military men who he regarded as brethren. Braxton Bragg had been given a reprieve. He returned to his command facing a superior enemy and dissatisfied subordinates, conditions not very promising for success.

BACK_TO_TOP* Don Carlos Buell was under judgement as well. His crawling and labored offensive through northern Alabama during the summer had made the President impatient. His failure to seriously engage, much less crush, the rebel invaders of Kentucky was more than Lincoln could tolerate. Buell tried to explain to his superiors that he had not followed the Confederates into the Kentucky barrens because the roads were bad and the land too inhospitable. He wanted to resume the interrupted offensive towards Chattanooga.

His superiors weren't listening. Halleck replied angrily on 17 October that Buell should "drive the enemy from Kentucky and East Tennessee. If we cannot do it now, we need never to hope for it." Halleck later added, reporting the President's continued failure to understand "why we cannot march as the enemy marches, live as he lives, and fight as he fights, unless we admit the inferiority of our troops and our generals."

Buell blandly replied on 20 October in a long, legalistic message that "the spirit of the rebellion enforces a subordination and patient submission to privation and want which public sentiment renders absolutely impossible among our troops" and concluded that "the discipline of the rebel army is superior to ours." Lincoln wanted winners, and this was not the stuff of which winners were made. On the 25th, Buell received a dispatch from Halleck:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

General: The President directs that on the presentation of this order you will turn over your command to Maj. Gen. W.S. Rosecrans, and repair to Indianapolis, Ind., reporting from that place to the Adjutant General of the Army for further orders.

END_QUOTE

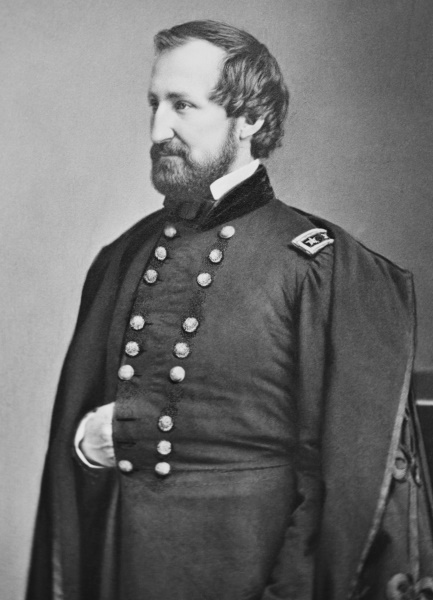

Major General William S. Rosecrans was the hero of the hour in the West for his victory at Corinth. He received instructions from Halleck that spelled out in completely specific terms what was expected of him: "Neither the country nor the Government will much longer put up with the inactivity of some our armies and generals." Lincoln's patience with both the rebels and his generals was now at an end. Buell would remain idle in Indianapolis all through 1863, waiting for orders. They never came, and he would resign from the Army in the spring of 1864.

Buell's dismissal had an odd result. Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis, under arrest for the killing of William Nelson, eventually found himself a free man. In the confusion of the war his case was generally forgotten, and having the powerful Governor Oliver H.P. Morton on his side didn't hurt, either. He returned to duty with his rank intact, having literally gotten away with murder. No doubt, his fellow officers were very careful not to step on his toes.

* When Rosecrans inherited what had become known as the Army of the Cumberland from the unfortunate General Buell, he also inherited all of Buell's problems. A third of the army was either sick or absent without leave, and many of those still in the ranks were miserably drilled and equipped. The most overwhelming of these problems, however, was the army's exposed position at the end of a long and tenuous supply line. When Rosecrans marched the troops back into Nashville on 7 November after their long campaign in Kentucky, not only was the army in ragtag shape, but his means for improving their condition were limited.

Rosecrans was made of harder stuff than Buell. Rosecrans, then 43, was a volatile, contradictory, energetic man, quick to rage, just as quick to forgive. He was a devout convert to Catholicism who heard mass every morning, who carried a crucifix on his watch-chain and a rosary in his pocket. He was also notorious for hard drinking and foul language, though he was careful to draw the line between profanity and blasphemy. He was popular with the men, who enjoyed a general they could talk to and even share jokes with, nothing at all like the cold-fish Buell. They called him "Old Rosey" and "Fighting Rosey", with the hidden joke that "Rosey" also described the general's big red boozy nose.

If he found a soldier wearing worn-out boots or the like in an inspection, he would tell the man emphatically: "Go to your captain and tell him what you need! Go to him every day until you get it! Bore him for it! Bore him in his quarters! Bore him at meal time! Bore him in bed! Don't let him rest!" He would continue at length, explaining that the request would eventually make its way up the chain of command where at the top he would personally "see then if you don't get what you want!"

Although the soldiers liked Rosecrans, he wasn't greatly admired by his fellow generals -- being competent and energetic at times, muddled and pig-headed at others, inclined to the erratic. Before his reassignment, he had reported to Grant; Grant had been thinking of sacking him, and wasn't so unhappy to get rid of him. Rosecrans was happy to be rid of Grant in turn, and was putting his best foot forward in his new command.

Rosecrans was confronted with a troublesome logistical situation. The rivers were still too low for effective navigation, and the few rail lines were continually harassed and cut by Confederate raiders. Rosecrans organized long wagon trains into Nashville while his men rested and refit. With his supplies dependent on such unreliable connections, Rosecrans wanted to get at least two million rations on hand before he advanced.

There were other problems to attend to. Nashville was a rebel city and the population was barely under control, something like a Baltimore of the West. The army provost marshal of the city, John Fitch, complained that it was "swarming with traitors, smugglers, and spies." Fitch observed that most of its male citizens were fighting in the Confederate army, and the women they left behind were "arrogant and defiant, outspoken in their treason and indefatigable in their efforts" to aid their menfolk fighting the Federals. Rosecrans would have no such insubordination. He organized both regular police and secret police organizations that came down hard on troublemakers and suspicious characters, arresting them to throw them behind bars or send them over rebel lines.

Similarly, demoralized Federals were often surrendering to the Confederates so they could be paroled and sent home. Rosecrans had men suspected of playing this game marched through the streets and camps wearing a white cotton nightcap, to advertise them as cowards before they were sent home. No doubt, in the fine tradition of military justice, men innocent of wrongdoing were punished in this way, but the number of defections still fell considerably. Rosecrans also demanded, and got the right, from Secretary Stanton to summarily sack officers guilty of serious misconduct. To his men, Fighting Rosey meant business.

* Rosecrans' Confederate opponents were facing even greater difficulties. Roughly 15,000 of Bragg's men who had come back from their round-trip offensive into Kentucky ended up on the sick list, and the 27,000 who were still up and about were hard-pressed to just stay fed and warm. Snow was covering the ground by 1 November, the winter promised to be harsh, and to compound the difficulties such supplies as could be obtained were being shipped over the mountains to support Confederate operations in the East, which were being given priority at the time.

The rebels were still doing what they could to fight back. John C. Breckinridge had arrived in Chattanooga in early October with 2,500 men. He was reinforced by an additional 2,500 exchanged prisoners -- but as he prepared to march north to join Braxton Bragg in Kentucky, he got word from Bragg that the Confederates were withdrawing south. Breckinridge was ordered to proceed to Murfreesboro with his men and wait for the arrival of Bragg and his troops. Breckinridge arrived in Murfreesboro on 28 October, joining Bedford Forrest, who had been using the town as a base for small-scale raids.

Breckinridge was alarmed at the vulnerability of the forces under his command. Although there was only one Federal division in Nashville to the north, Breckinridge was still outnumbered; once Rosecrans marched his forces into Nashville, Union superiority would be overwhelming. On 6 November, Breckinridge ordered Forrest and Morgan, who had returned from the Kentucky expedition in advance of Bragg's army, to perform cavalry raids on Nashville to throw the Federals on the defensive. Forrest felt they could have seized Nashville, but the arrival of Rosecrans' Army of the Cumberland the next day made the prospect much more difficult.

In the meantime, Bragg was shifting the rest of his men down through Chattanooga and then on towards Murfreesboro. When the troops began to arrive there in early November they found that Bragg, a skillful logistician, had managed to at least have stockpiled plenty of food to eliminate hunger from their list of miseries. The division Edmund Kirby Smith sent in support arrived a few days later, bringing the total of soldiers and cavalry under Bragg's command to a total of almost 50,000. Bragg was enthusiastic about his prospects. With drill and effort, the forces under his command, now dignified with the title of the Army of Tennessee, might well throw the Federal invaders out of Tennessee -- even though the Confederates were still well outnumbered.

Although the progress of the Yankees down the Mississippi and towards Chattanooga had been halted, the Federals were obviously gathering strength for another push. Jefferson Davis realized that the Confederate defense of the West was weak and disjointed, and so on 24 November 1862 he assigned General Joe Johnston overall command of the entire Western theatre of war. Although Davis had a bad relationship of long standing with Johnston, he was one of the few generals the Confederacy had with sufficient stature for such an important command.

Johnston was in charge of Bragg's forces at Murfreesboro, as well as Confederate forces defending Vicksburg against Grant. Davis also encouraged Smith to send assistance to Bragg and Smith did so, sending his strongest division. That was a remarkable act for Smith, who began the Kentucky campaign with a total lack of cooperation with Bragg and had ended it with nothing good to say about him. However, Smith was a great admirer of Davis, and Davis had done an extremely good job of placating Smith during the general's visit to Richmond. In fact, Bragg and Smith would reconcile their differences, and be on good terms from that time on.

Unfortunately, the friction between Jefferson Davis and Joe Johnston remained in effect. Johnston was not pleased with the strategic situation as he found it. His two major forces were relatively weak and faced with superior Union military strength, with Grant preparing to move on Vicksburg and Rosecrans building up supplies for an advance on Murfreesboro. Johnston proposed that he consolidate his forces and then smash Rosecrans. Grant would be then isolated and forced to retreat. Davis rejected the proposal, suggesting in turn that Johnston send forces from Bragg to support the defense of Vicksburg. Johnston replied that Confederate forces in Arkansas would be more appropriate to the task. Davis and Johnston could never agree on anything.

* While Braxton Bragg consolidated his rebel army in Murfreesboro and William Rosecrans accumulated supplies for a Federal offensive from Nashville, the war in Tennessee was not idle, thanks to the energetic efforts of John Hunt Morgan and Nathan Bedford Forrest.

On 6 December, Morgan moved to attack the Federal garrison at Hartsville, 35 miles (56 kilometers) northeast of Nashville. The Yankees there were protecting Rosecrans' vital rail lifeline to Louisville. Morgan led six infantry regiments and one cavalry regiment across the snow and the icy Cumberland River. Morgan was hoping to catch the Union men by surprise at sunup, but the river crossing led to delays, and the Federals were waiting. Morgan's men pressed the attack anyway, their charges finally crowding the Yankees up "like sheep in a pen". After an hour and a half of fighting, the Federal commander, Colonel Absolom B. Moore, surrendered his 1,800 men. Morgan's soldiers torched everything they could not carry off, and marched their captives back to Murfreesboro.

Jefferson Davis was pleased, but his dissatisfaction with the conduct of the war in Tennessee and along the Mississippi was growing. In fact, Davis regarded the situation so critical that he performed a personal inspection, arriving in Murfreesboro on 10 December. There, he ordered Braxton Bragg to send a 9,000-man division to reinforce Vicksburg. When Bragg protested that he would almost certainly be defeated if he lost more men, Davis replied that he would have to stand as best he could, and then withdraw over the Tennessee River. Losing central Tennessee to the Yankees would be a major setback, but losing Vicksburg would be a strategic catastrophe. The division marched off.

There was some ceremony to the visit. Before he left on 13 December, Davis awarded Morgan the rank of brigadier general as a reward for his victory at Hartsville. Morgan, in fact, was on top of the world at the moment: not only had he been made a general, but he was in love. During the summer, when the Federals were still occupying Murfreesboro, a 17-year-old citizen of the town had overheard Yankee officers speaking ill of Morgan and had jumped sharply to the defense of his good name. One of the Federals demanded her name, and she proudly replied: "It's Mattie Ready now, but by the grace of God one day I hope to call myself the wife of John Morgan!"

The story got back to the widower Morgan, and not too surprisingly he looked up the girl. He found her "pretty as she was patriotic" and proposed to her. They were married on 14 December by Bishop-General Polk, and the ceremony was an occasion for celebration among Confederate troops and the enthusiastically pro-rebel citizens of Murfreesboro. There was so much celebration, in fact, that the discipline of the Confederate Army of Tennessee unraveled a bit. According to a story that made the rounds at the time, a new recruit was given a dollar and told to go buy food and drink from the sutler. He came back with 90 cents worth of whiskey and 10 cents worth of food, and was chewed out for buying so much food.

Some of Morgan's men worried that their commander was overly distracted by the company of his new wife. "They say we are a love-sick couple," Mattie wrote shortly after the wedding. However, the next week he took them raiding again north into Kentucky, striking fear into the Yankees and in general raising hell. He and his men got back to their starting point in early January after having taken almost 2,000 prisoners, burned two major railroad trestles and four bridges, and destroyed almost two million dollars of Federal supplies, at minimal cost to the raiding party.

Even before Morgan had set out, on 10 December Forrest received orders from Bragg instructing him to "throw his command rapidly over the Tennessee River and precipitate it upon the enemy's lines, break up railroads, burn bridges, destroy depots, capture hospitals and guards, and harass him generally." The objective was to hinder Grant's offensive operations against Vicksburg. Forrest would do a very good job of hindering Grant -- but for the moment, neither Morgan nor Forrest were causing direct trouble for Rosecrans.

While all this was happening, Rosecrans remained on the defensive, despite loud complaints from Washington. In response to War Department prods, he replied that he wanted to "lull [the rebels] into security", then "press them solidly", and "endeavor to make an end to them." His superiors were tired of delays and rationalizations. On 4 December, Rosecrans received a message from Halleck:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

The President is very impatient at your long stay in Nashville. The favorable season for your campaign will soon be over. You give Bragg time to supply himself by plundering the country your army should have occupied. Twice have I asked to designate someone to command your army. If you remain one more week at Nashville, I cannot prevent your removal.

END_QUOTE

Rosecrans replied blandly: "I need no other stimulus to make me do my duty than the knowledge of what it is. To threats of removal or the like I must be permitted to say that I am insensible." Fighting Rosey would move when he damn well thought he was ready to move.

BACK_TO_TOP