* Lee, having failed to crack the Union position through the northern hills of Gettysburg on 1 July, decided the next day to shift forces and attack in the hilly terrain to the south, with Longstreet marching the troops to battle. The movement was complicated by the unexpected presence of Federal troops in a peach orchard along the line of march, leading to a violent confrontation. The Confederate assault to the south was delayed, with Meade able to shore up his defense there, leading to a succession of fights that gained the rebels nothing. As the attack in the south faded out, in the evening there was renewed fighting in the northern hills that also proved inconclusive.

* Meade had placed the Army of the Potomac to take advantage of Gettysburg's terrain, but had no plans to start a fight himself. If there was to be fighting that day, Robert E. Lee would have to take the initiative.

Lee was more than willing to attack. He woke before dawn, ate breakfast in the dark, and as the sun began to rise examined the Federal positions with his field glasses. He saw that the Union line was weak or nonexistent along Cemetery Ridge, and felt his chances of success were good.

Longstreet arrived at headquarters, reporting that Hood and McLaws were moving up on the battlefield with the bulk of their divisions, but Pickett would not be able to arrive with his division before evening at earliest. Longstreet then startled Lee by suggesting once again that the Army of Northern Virginia move to place themselves between the Army of the Potomac and Washington DC. Longstreet still wanted to conduct a defensive battle, instead of an offensive one against an enemy in a solid position. That was reasonable, underlined by the fact that Federal reinforcements were even then pouring into the previously open length of Cemetery Ridge and the hills to the south -- but Lee seemed to be in an unreasonable mood, and simply rejected Longstreet's plan.

To be sure, Lee no longer had the services of Stonewall Jackson, one of the great masters of the war of mobility; and with Jeb Stuart absent, Lee had no good way to keep track of the movements of the Army of the Potomac. Under the circumstances, Lee had good reason to believe that if he tried to dance around the Federals on their own home ground, he might very well stumble into a trap himself.

Longstreet was not a thin-skinned man, as were so many rebel generals, but Lee's rejection of his proposal only increased his doubts. He fell silent. Other officers arrived. A.P. Hill came up, though he was still feeling poorly and had little to say. Henry Heth was there, but his head was wrapped in bandages from his brush with a bullet the day before, and he was in no condition to fight. John Hood rode up, and Lee told him, pointing to the masses of blue troops to the east: "The enemy is here, and if we do not whip him, he will whip us."

Hood thought that meant he would be in a fight immediately, a circumstance usually much to his liking, but Longstreet took him aside and said: "The general is a little nervous this morning. He wishes me to attack. I do not wish to do so without Pickett. I never like to go into battle with one boot off."

Lafayette McLaws arrived at about 08:00 AM, and Lee took him aside and instructed him to take his division south along Seminary Ridge to attack the southern end of the Union position. McLaws was prepared to do as he was told, but Longstreet, who had been left out of the conversation and was clearly annoyed at Lee violating the chain of command, broke in and told McLaws: "No sir, I do not wish you to leave your division!" Longstreet traced out a different position on the map and told McLaws: "I wish your division to be placed so."

Lee replied to Longstreet with forced patience: "No, General, I wish it to be placed just opposite." Longstreet, who was not pigheaded but was certainly independent-minded, refused to agree; McLaws left in some embarrassment to wait for clear orders. Once again, Lee's normal reasonableness seemed absent: Longstreet was clearly at odds with him, but Lee did not see it necessary to take the time to talk the matter out with his chief lieutenant, which is likely the issue that was bothering Longstreet most of all. Lee may not have been in good health. Some witnesses later reported that Lee was suffering from diarrhea, and others hinted at symptoms of the heart disease that would kill him some years later.

Lee was encouraged in his offensive thinking by receiving reports that the southern end of the Union position was very weakly held. He concluded that Longstreet would move south along Cemetery Ridge, as he had earlier told McLaws, and roll up the Army of the Potomac from the south. Instead of giving specific orders at the moment, however, Lee rode over to confer with Ewell to make sure that both wings of the Army of Northern Virginia were moving in coordination. On arrival, Lee told Ewell that the northern end of the Federal position was almost certainly too strong to be taken, but that Ewell would need to make a demonstration against it to prevent Meade from moving his forces south to meet Longstreet's assault. Lee added that if the demonstration seemed to be making headway, Ewell could escalate to a full-scale assault.

Lee rode back to his headquarters, where he gave Longstreet his orders. Longstreet asked for a short delay to wait for the arrival of another one of his brigades, and Lee agreed, though not happily. The troops went into motion around noon.

Nearly all of the forces available to Lee were committed to the battle, except in particular for Heth's division, which had been too badly chewed up in the fighting the day before to be combat-effective. However, despite the clear importance of the attack, Lee's management of it was startlingly loose: he neither issued written orders, nor even brought the corps commanders together to confer.

* As Longstreet's men moved out, Jeb Stuart and his 4,800 cavalrymen finally rejoined the Army of Northern Virginia. After moving out on 25 June, that evening Stuart had found Hancock's II Corps blocking communications with the rest of Lee's army. Even Stuart wouldn't consider slugging it out with an entire Federal army corps, and so he prudently decided to circle around it. That led to a long detour south and east that actually took Stuart and his men farther away from the main Confederate force, with the Union Army of the Potomac blocking direct routes by which the rebel cavalrymen might be able to link up with the rest of their army.

Stuart crossed the Potomac at Rowser's Ford, not far upstream from Washington, and moved towards Rockville, Maryland, where they pounced on a Federal wagon train, capturing 900 mules and 125 wagons fully loaded with supplies, along with 400 prisoners. Stuart and his men moved out of Rockville on 28 June, cutting telegraph and railroad lines and fighting intermittent skirmishes with Union army and militia units. However, the wagons that the rebels had seized slowed down their progress, and their way west was still blocked by the Army of the Potomac. All Stuart could do was lead his men north and hope for a break.

They reached York, Pennsylvania, on 30 July, to find that Jubal Early's division had been there momentarily and then left. The troopers went further north to Carlisle, where on 1 July they got into a fight with local militia.

Lee had sent out eight couriers to look for Stuart, and one of them caught up with him that evening. In the dark hours of the morning of 2 July, Stuart and his men went off on a night ride towards Gettysburg, arriving about midday. On meeting Stuart, Lee's restrained but fierce temper seemed to be close to exploding. He raised a hand angrily and said: "I have not heard a word from you for days, and you are the eyes and ears of my army!"

Stuart, deeply cut by the reprimand, answered feebly: "I have brought you 125 wagons and their teams, General."

"Yes, and they are an impediment to me now!" One of Lee's staff described the scene as "painful beyond description". Then Lee regained his self-control, likely reminded himself of the many remarkable things Stuart had done for him in the past, and went on "with great tenderness": "Let me ask your help now. We will not discuss this matter further. Help me fight these people." However, Stuart and his men would not participate in the day's fighting.

By that time, Longstreet and his men were on the march. There was plenty of Federal activity on the Round Tops, the prominent hills at the southern end of the Federal line, and nearby terrain, but Lee felt that the Union defense was still vulnerable in that area. That might have been the case when he made the decision to shift in that direction -- but Longstreet's march south proved to be anything but straightforward and quick. The rebels needed to make their move unseen by the Yankees, and staying behind the hills required roundabout marching, made even more complicated by ignorance of the terrain. Longstreet's men found him gloomy.

At last, at about 03:00 PM, Longstreet's three divisions reached their objectives and prepared for attack. They were, however, confounded to find that a large mass of Federal troops were lurking in a peach orchard astride their lines of attack.

BACK_TO_TOP* In the morning, Union General Meade had been inspecting his lines and ran into Major General Carl Schurz on Cemetery Hill. Schurz found Meade obviously weary, and asked how many men would be available for the battle. Meade replied: "In the course of the day, I expect to have about 95,000, enough I expect for this business." Meade added: "We might as well fight it out here as anywhere else."

Meade had expected an attack from Ewell, and so the greater part of the Army of the Potomac was massed in the north of the Federal position. Slocum's XII Corps held the line from Culp's Hill to the east; the other side of Culp's Hill was held by survivors of Wadsworth's I Corps division; and Cemetery Hill was held by Howard's XI Corps. Hancock's II Corps was set up along Cemetery Ridge, and Sickles' III Corps held the southern end of the position.

Two I Corps divisions were held in reserve on Cemetery Hill. Some of the I Corps soldiers were feeling irritable, since Meade had relieved Abner Doubleday from command of the corps after hearing Howard's reports that I Corps troops had broken and run. That was an excessively negative reading of the true events, but Meade still had replaced Doubleday with Major General John Newton of VI Corps. I Corps troops had found Doubleday's conduct during the fight commendable, and grumbled about the injustice.

V Corps, which had been under Meade's command less than a week earlier and now under Major General George Sykes, was also held in reserve in a central location behind Cemetery Hill. Major General John Sedgwick was bringing his VI Corps to the battle by a forced march, but VI Corps wasn't expected to arrive until that afternoon. Sedgwick's VI Corps, at 14,000 men the biggest single element of the Army of the Potomac, would be a powerful asset when it arrived.

Lee's delay in attacking bothered Meade. He knew Lee was not one to waste time, and wondered what he was up to. Meade considered launching an assault of his own, but decided against it, and in fact drew up contingency plans for withdrawing the army from the battlefield if it came to that.

During the night, a XII Corps division under Brigadier General John Geary -- once territorial governor of Kansas -- had been holding the southern end of the Union position, with two regiments occupying the vital high ground on Little Round Top. Early in the morning, Geary had been ordered to pull his division out and rejoin the rest of XII Corps at Culp's Hill, while Sickles' III Corps moved in to replace them. He informed Dan Sickles of the need to ensure that the Round Tops were adequately defended, but Sickles ignored him. Geary was forced to withdraw, leaving the Round Tops unprotected.

Dan Sickles was worried about other things. Cemetery Ridge dropped slowly in height as it ran south, fading out almost completely before it met the Round Tops, and Sickles feared the rebels would occupy higher ground to the west and shoot down on his troops. Sickles had witnessed the harm that had come to the Federals when they abandoned the high ground to the rebels at Chancellorsville, and so he reported to a courier sent from headquarters, a Captain George Meade, General Meade's son, that III Corps was "grievously exposed". Meade had little respect for "political generals" such as Sickles, with Sickles having a bad reputation on several counts on top of that, and ignored the warning.

That worried Sickles even more, since Hooker had similarly ignored Sickles at Chancellorsville, with disastrous results. At midmorning, Sickles went personally to Meade's headquarters on the Taneytown Road, just behind the center of the Federal line, and asked Meade if he could post his troops where he thought wisest. Meade replied: "Certainly, within the limits of the general instructions I have given you. Any ground within those limits you choose to occupy I leave to you." Meade sent Brigadier General Henry J. Hunt, his chief of artillery, along with Sickles to see if there really was a problem.

Hunt agreed that Sickles had a point, his position was exposed to the front, but noted that if Sickles moved forward his forces would be unsupported, making them easy to cut off and destroy. Despite this feedback Sickles remained worried, and Hunt promised to talk the matter over with Meade.

Sickles heard nothing more about the matter. Then he learned that John Buford's cavalry, which had been patrolling the south end of the line, had been assigned elsewhere without any other units being sent to plug the hole they left behind them. Sickles grew even more distressed. Sometime after noon, on a suggestion from Hunt, Sickles sent out Colonel Hiram Berdan with four regiments of his elite sharpshooter brigade and a Maine infantry regiment to scout things out. Berdan's Brigade advanced to the west and got into a nasty fight with Longstreet's men that lasted about 20 minutes, with Berdan finally withdrawing his men to report back to Sickles.

On being told the rebels were moving large numbers of men around the southern end of the Union position, Sickles decided to take matters into his own hands. At about 03:00 PM, the two divisions of III Corps marched west, in such formality that some observers judged it as grand as a dress parade, to occupy the high ground in a peach orchard to the west. Sickles deployed one of his divisions, under General Andrew Humphreys, on the northern section of his new line, and the other, under General David B. Birney, on the southern section.

The men of Hancock's II Corps on Cemetery Ridge watched this procession in astonishment. The whole move seemed so deliberate that John Gibbon, who was chatting with Hancock, wondered if the II Corps was supposed to advance as well and didn't get the order. Hancock dismissed the idea: "Wait a moment, you'll see them tumbling back." In fact, many of Sickles' own men realized they were dangerously exposed, being baffled and frightened by the move: "Stuck out like a sore thumb," as some put it. Sickles' line was disconnected from Hancock's II Corps on the north, and weakly anchored to the south.

Meade had called a council of war. Sickles, busy with his redeployment, had not wanted to attend, but Meade told him to drop what he was doing and come anyway. As Sickles rode up to Meade's headquarters, rebel cannon fire started to boom from the south. Meade told Sickles to not bother to dismount, called off the meeting, and ordered Sykes to move V Corps up to support III Corps. Meade had to gamble that VI Corps would arrive soon enough to act as a reserve against emergencies elsewhere.

Meade rode after Sickles to see what the trouble was. Meade was undoubtedly unhappy at what he saw when he arrived, but likely realizing that his instructions to Sickles earlier in the day had unhelpfully contributed to the situation, did his best to restrain his notorious bad temper. Meade said calmly: "General, I am afraid you are too far out." Sickles tried to explain that he had obtained higher ground, but Meade cut him short with strained patience: "General Sickles, this is in some respects higher ground than that to the rear, but there is still higher in front of you, and if you keep on advancing you will find constantly higher ground all the way to the mountains."

Sickles felt he could hold out if he got support, but indicated that he would withdraw if Meade wished him to. Rebel artillery was already probing the Peach Orchard, and Meade replied: "I think it is too late. The enemy will not allow you." However, Sedgwick's VI Corps was arriving on the battlefield and Meade now had more forces he could call on to help pull Sickles out of his jam. Meade told Sickles that he would get support, but then a nearby blast caused Meade's horse to bolt, with Meade trying to keep the animal from galloping into enemy fire. He finally managed to get the beast under control and rode off to get support for Sickles. Meade directed Sykes toward the fight and ordered Hunt to bring up artillery.

Hunt reacted quickly, pulling up guns from the artillery reserve and setting them up behind the Peach Orchard. Confederate guns were hitting the Peach Orchard heavily by this time. Hunt's gunners responded, focusing on enemy batteries and trying to knock them out one by one.

* Sickles' advance into the peach orchard was clearly a blunder -- but even at that, it did much to bewilder the Confederates and confound their plans. The presence of Sickles' III Corps confounded two of Longstreet's division commanders, McLaws and Hood. McLaws later wrote: "The view presented astonished me, as the enemy was massed in my front, and extended to my right and left as far as I could see." That was particularly startling since McLaws had been told he would face little opposition. If Sickles' men were exposed to attack in their forward position, that position also allowed them to strike at a rebel advance along their flanks. The two rebel generals also realized that even if that hadn't been the case, the Federals were present in force to their front and holding strong positions.

Both McLaws and Hood complained about the matter to Longstreet, who stubbornly insisted that they proceed with their assaults as ordered by Lee. McLaws later wrote to his wife that Longstreet was "exceedingly overbearing". Longstreet was proving as unreasonable that day as Lee: nobody ever accused John Bell Hood of any timidity in combat, and if Hood didn't like the look of things, there was very likely something seriously wrong. Longstreet was cross and petulant, though he did order his artillery to take the Peach Orchard under fire.

In between the exposed Yankee position in the Peach Orchard and the Little Round Top there was a wheat field, leading to a field strewn with great boulders known as the Devil's Den, and then to a shallow valley containing a stream named the Plum Run. Birney's men had set up a thin line through the wheat field and the Devil's Den down into the Plum Run.

After the artillery fight over the Peach Orchard had gone on for some time, Hood's division jumped off with an infantry assault at 4:00 PM, led by Brigadier General Evander Law's brigade of Alabamans. Their orders were to attack parallel to the Emmitsburg Road, taking them through the Peach Orchard towards Cemetery Ridge. Law felt that such a move would leave his men open to fire from the Devil's Den and the Round Tops, and so he simply disobeyed orders. He charged into the Devil's Den towards the Little Round Top instead, since rebel scouts had indicated it was unoccupied. This proved yet another misjudgement for the day. The broken terrain in the Devil's Den did not lend itself to an orderly advance and the combat there broke down into wild, confused, and extremely violent fighting. Hood's two other brigades joined the battle in the Devil's Den, and Hood himself went down with an arm shattered by a bursting shell.

Sickles shifted a brigade from Humphreys' division to help Birney, and George Sykes sent in two brigades from General James Barnes' division as well. It wasn't enough to stop the flood. Yankee and rebel units fought among the stones of the Devil's Den and alongside the Plum Run with little coordination and extreme ferocity. The combat was so disorganized that one Confederate recalled that it reminded him of "Indian fighting". There was so much killing along the Plum Run that it later was referred to as the "Valley of Death". However, Birney's men held a line against the rebel advance, and the Confederates found the Federals very unwilling to give an inch.

BACK_TO_TOP* While this nightmare was taking place, two of Law's regiments under Colonel William Oates veered around to the south and charged up the Round Top. They cleared off a group of troublesome Yankee sharpshooters and gained the top of the hill, though the rebels took substantial casualties in the process. The Round Top was heavily wooded, limiting its usefulness, but it still overlooked the Federal positions to the north, and if the rebels could manhandle some rifled guns to the summit and start chopping down trees they might well unhinge the Union defense.

However, a courier sent by Law arrived with orders for Oates to seize Little Round Top. Oates objected, but since the Little Round Top did not seem to be held in force by the Federals, sent his tired men forward anyway. As Oates' two regiments reached the bottom of the valley between the two hills, they were joined by another Alabama regiment and two regiments of Texans that had fought their way through the Devil's Den. The troops charged up the Little Round Top, only to be met by a heavy volley of rifle fire and canister that blasted them back. It appeared the Little Round Top was in fact held in force. Oates knew he had a real fight on his hands. He regrouped his men to charge again.

The Yankees on the crest of Little Round Top had just arrived. The chief engineer of the Army of the Potomac was Brigadier General Governeur Kemble Warren, who as a colonel in charge of a New York regiment had taken the brunt of Longstreet's flank attack at Second Bull Run. Warren was a slight-looking New Yorker who was in reality a cool and tough soldier. Warren had come with Meade to investigate the trouble. He had been inspecting the hill when the shooting started, and when he asked an artillery officer to pop a shell into nearby woods, saw a shuffle of activity that indicated the rebels were trying to perform a flank attack.

Warren quickly realized that if some troops weren't rushed to the top of the Little Round Top immediately, the whole Union line would be in critical danger. Warren sent a messenger to Meade to warn him. Another messenger, Lieutenant Ranald MacKenzie, was sent to get help from Sickles -- but Sickles had his hands full, and MacKenzie went to George Sykes instead to ask for help.

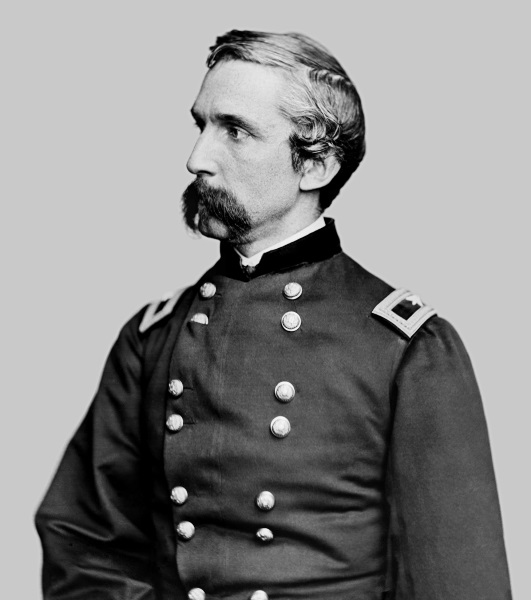

Sykes had a reputation for sluggishness but he sent help immediately, in the form of a brigade under Colonel Strong Vincent. Vincent, at 26 the youngest brigade commander in the US Army, was a Harvard graduate, and although his men had originally thought him a "dude and an upstart", they eventually recognized that he was a solid combat leader. The brigade went to the hill immediately. Vincent's brigade consisted of four regiments, one each from Pennsylvania, New York, Maine, and Michigan. The Maine regiment was the 20th Maine, under the command of Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain. Vincent sent the 20th Maine to hold down the far end of the line and told Chamberlain: "This is the left of the Union line. You understand. You are to hold this position at all costs."

Chamberlain was an interesting case, originally a professor from Bowdoin College in Maine. When war broke out, he had asked for a leave of absence to join the Union cause. He was refused, asked for a sabbatical to study in Europe, and then joined the Union Army anyway. Although his background might not have suggested it, and there were those in authority who had judged him unsuited to the command of a regiment, he was a natural soldier and leader of men -- tough, intelligent, and conscientious. The rebels charged Chamberlain and his men several times, and finally the 20th Maine was almost out of ammunition, with half their men down. Chamberlain knew they could not withstand another charge; for lack of anything better, he passed the order down his line to fix bayonets and prepare to countercharge the next assault.

In fact, the rebels were at the end of their own tether, but Oates ordered one last charge. The Confederates threw themselves forward again, only to be greeted by a mad rush of screaming Maine men that complete unnerved them. Chamberlain had also detached B Company of the 20th Maine to go east around the hill and protect the regiment's flank at the beginning of the fighting. They had been pinned down, but now finally decided to make their presence felt. Confederate soldiers were caught in a crossfire, with some being hit by multiple bullets coming from several directions at once. One rebel officer was handing his sword in surrender even as he fired his pistol with his other hand. Oates admitted: "We ran like a herd of wild cattle." A captured rebel, of the roughly 400 prisoners taken by the 20th Maine, later said he hoped to "never see them damned fellers from Maine again."

* In the meantime, Warren had personally helped manhandle two guns of First Lieutenant Charles Hazlett's battery to the top of the hill to lend their weight to the defense. Warren then went back down the hill to get more help. However, the other regiments of Vincent's brigade began to crumble, and Vincent was killed with a bullet through the heart.

After riding back down the hill, Warren had found a brigade under Brigadier General Stephen Weed marching towards the destruction in the Peach Orchard, and ordered the regiment to change direction and move up to support the fight on the Little Round Top. By good fortune, one of the four regiments in this brigade was the 140th New York, which had once been Warren's regiment, and was now under 23-year-old Colonel Patrick O'Rorke. O'Rorke protested that he had orders to help Sickles, but Warren replied: "Never mind that, Paddy. Bring them up on the double-quick, and don't stop for aligning. I'll take the responsibility."

O'Rorke's brigade arrived just as the rebels began to break through, and charged into the Confederates without hesitation. The New Yorkers didn't even stop to load weapons or fix bayonets, they just threw themselves at the rebels and literally pushed the rebels back down the steep hill with their rifles and whatever they could throw. O'Rorke was shot and killed in the collision; the survivors got into line and started shooting. Weed's other regiments arrived just behind them, and blazed away at the rebels; he was hit by a bullet shot by a rebel sharpshooter that went through his shoulders and cut his spine. Lieutenant Hazlett leaned over to help the injured Weed and took a bullet in his head, killing him instantly.

The Confederates were taking heavy casualties themselves, and unlike the Federals they were not getting reinforcements. The rebels fought aggressively but the odds were too long, and they soon had to give it up, falling back down to the base of the hill to trade shots with the Yankees above them. The saddle between the Round Tops accumulated so many Confederate dead through the fighting that it later became known as the "Slaughter Pen".

Longstreet held back from committing Lafayette McLaws' division to the fight. If Hood's men could crack the Federal defense, well and good; if they could not, then by shifting the weight of Federal forces south they might well weaken the Union line in front of McLaws farther north.

One of McLaws' four brigade commanders, the aggressive Brigadier General William Barksdale from Mississippi, had begged McLaws for permission to attack, partly to relieve the terrible pressure on Hood's men, partly because there was a fight going on and Barksdale did not want to be left out of it. McLaws told him to wait for the order.

It came at about 05:30 PM, and three of McLaws' brigades moved in succession into the wheat field north of the Devil's Den. They collided with the Yankee defenders, under Barnes and Birney, and the fighting rose to the same level of fury that had characterized the battle to the south for the last hour and a half. One of McLaws' brigade commanders, Brigadier General Paul Semmes -- younger brother of the famed raider captain Raphael Semmes of the Confederate Navy -- fell mortally wounded on the field.

Barnes and Birney realized that their position in the Wheat Field was crumbling. Barnes cried out: "It is too hot, my men cannot stand it!" The Union line broke. McLaws' men pushed forward to exploit their success and promptly ran into a countercharge from a division under General James Caldwell that had been sent by Hancock to deal with the emergency.

Caldwell's division had four brigades. The first was under Colonel Edward E. Cross; within minutes, Cross himself was out of the fight, seriously wounded. Cross's brigade was followed by that of Brigadier General Samuel K. Zook. His troops ran into Barnes' men fleeing the field, and he shouted at them in a rage: "IF YOU CAN'T GET OUT OF THE WAY, LIE DOWN AND WE WILL MARCH OVER YOU!" Surprisingly, that's exactly what they did, and Zook's brigade moved forward over them. Zook was then mortally wounded in the stomach.

The third brigade was the famous Irish Brigade, under Colonel Patrick Kelly, which moved into the gap between the brigades of Cross and Zook, and found themselves facing so many rebels that one officer said "a blind man" couldn't have missed them. Caldwell's fourth brigade, under Colonel John Brooke, followed. The assault degenerated into inconclusive, chaotic, and bloody fighting.

Just to the north, Barksdale had finally been given permission to lead his men directly into the Peach Orchard. It hadn't been a secure position in the first place and the attack sent the Federals "tumbling back", as Hancock had foreseen. One Union soldier later wrote: "The hoarse and indistinguishable orders of commanding officers, the screaming and bursting of shells, canister and shrapnel as they tore through the struggling masses of humanity, the death screams of wounded animals, the groans of their human companions, wounded and dying and trampled under foot by hurrying batteries, riderless horses and the moving lines of battle, all combined an indescribable roar of discordant elements -- in fact a perfect hell on earth."

Dan Sickles, who was riding around on the battlefield to rally his troops, was hit by a cannonball that almost completely tore off his leg above the right knee. Sickles fell to the ground with a thud and managed to improvise a tourniquet to keep from bleeding to death. A staff officer ran up to him and asked: "General, are you hurt?!" Sickles no doubt thought of calling the man a damned fool, but he replied: "General Birney must take charge now." Sickles was carried off the field on a stretcher. On hearing rumors that he was dead, he coolly took a cigar out of his pocket, lit it, and puffed away at it to reassure his men. Sickles may have not had the training to be a good general, but he had the dash for it.

The Confederate tide through the Peach Orchard did not flow far. The rebel advance stalled; when Barksdale angrily tried to rally them, he made a perfect target. According to legend, a Union brigadier ordered an entire company to shoot Barksdale, who was hit five times and fell.

Barksdale's men kept on coming, but Henry Hunt had foreseen something like this happening, and had lined up 40 guns on Cemetery Ridge to the rear, with infantry assigned by Meade to support them. The Mississippians ran into a vicious storm of canister; although they managed to make it to some of the guns, where the Federal gunners fought them with pistols and ramrods and whatever else they had, the attack was doomed. The surviving rebels fell back.

* Both Hood and McLaws had sent their divisions in sequence into the Federal defense. They had pressed the Yankees very hard, but both attacks had bogged down in blood and destruction. The rebels were not done with their attempts to break the southern end of the Union line, however.

Still farther to the north, General Richard Anderson's division faced a Federal defense that had been stripped to deal with the Confederate attacks, providing the rebels with a great opportunity. However, Anderson, who had been under Longstreet's command in almost all other battles he had fought, was now under A.P. Hill. Hill delegated much more authority to his lieutenants than Longstreet, and Anderson was somewhat confused by his freedom.

This confusion was compounded by further misunderstandings of Hill and Longstreet. Due to fuzzy instructions from Lee, Hill thought Anderson's division had been detached to Longstreet, while Longstreet thought Anderson's division was to remain under Hill's authority and operate in support of Hood and McLaws. Both Hill and Longstreet assumed the other was in charge of Anderson, and neither exercised much control over him. As a result, when Anderson's division jumped off towards the Union defenses on Cemetery Ridge at 06:20 PM, Anderson failed to give his brigade commanders clear instructions on objectives. Five brigades were supposed to attack, but the commander of one brigade became confused and failed to commit his troops fully, while the commander of another brigade refused to move at all, claiming that Anderson had told him not to move.

Although the defenders, the division under Brigadier General Humphreys, fought hard and pulled back in good order when pressed, the rebels made good progress on the field. By this time, Winfield Scott Hancock was in charge not only of Union II Corps but of the survivors of Sickles' III Corps. He had his hands full dealing with the continuing charges of Hood's and McLaws' men, and knew perfectly well that the Union center was weak. Now the Confederates were charging directly into the weak spot.

Hancock galloped north to order his divisions under John Gibbon and Alexander Hays to shift south and plug the gap. This would leave their old positions open in turn, but Hancock simply had to take that chance, choosing between a possible disaster in the future and a certain disaster in the present. He then rode back to the threatened line ahead of the troops. Gibbon and Hays were sending their men over at a run, but Hancock saw that they wouldn't make it there quickly enough, and something had to be done to buy a few minutes of time.

A regiment of Gibbon's division appeared on the scene. Hancock rode over at a gallop and asked the regimental commander: "What regiment is this?!" The commander, Colonel William Colvill, replied: "First Minnesota!" Hancock pointed down the shallow slope towards the lead troops of an Alabama brigade under Brigadier General Cadmus Wilcox, and asked: "Colonel, do you see those colors?"

Colvill said he did. Hancock replied: "Then take them." Colvill knew perfectly well it was suicide, but the First Minnesota drew up their lines and charged with fixed bayonets. Wilcox's Alabamans were somewhat disorganized and winded by their long run towards Federal lines. The Minnesota's charge blunted their momentum; enraged, the Alabamans tore the badly outnumbered Minnesotans to bits.

It bought Hancock ten minutes, more than he needed; when the Confederates resumed their advance, they found themselves in a storm of lead from Gibbon's men, as well as from Henry Hunt's massed artillery, which Hunt had turned to fire northward. One by one, Anderson's brigades, lacking support and reinforcements, gave up their charge and pulled back. A Georgia brigade under Brigadier General Ambrose R. Wright managed to make it into the Union line and onto the top of Cemetery Ridge. Wright saw Federal soldiers falling away from the battle behind the ridge, but these were only men who were faint-hearted or had taken more than they could endure, while much greater numbers of fresh Yankee reinforcements were threatening him and his men from north and south. Wright, too, gave up the fight and withdrew in a hurry.

BACK_TO_TOP* Earnest fighting on the southern end of the Union line finally fizzled out, though bloody squabbling continued until darkness finally put a stop to it. However, the Confederates were not quite done for the day.

Dick Ewell didn't move all morning and remained idle into the afternoon, while his officers and men watched the Federals in front of them dig in deeper and deeper. When Longstreet's guns went off to the south at about 04:00 PM, Ewell ordered his batteries to set up on a high spot named Benner's Hill east of Gettysburg to bombard the Federal positions on Culp's Hill. Ewell intended to watch the reaction of the Federals to see if a serious assault on Culp's Hill was possible.

The Confederate guns started firing about 05:00 PM. They definitely got a reaction, and it was immediate and violent. Benner's Hill was lower than Culp's Hill and offered little cover, while Culp's Hill was almost a natural fortress that its occupants had strengthened considerably since moving in the evening before. Federal counterbattery fire was accurate and heavy, and the rebel gunners suffered heavily. Their commander, 20-year-old Major Joseph Latimer, Ewell's chief of artillery, was among those killed.

Finally, Ewell withdrew all of the guns except four, which were to support an infantry assault. Going ahead with the attack might have seemed like a crazy idea, given how clearly strong the north end of the Federal line was -- but in fact, Culp's Hill and Cemetery Ridge were lightly held. Meade had been forced to pull most of the fresh troops from those positions to deal with the Confederate attacks on the southern end of his line.

Culp's Hill was held by what was left of Wadsworth's division after its severe losses of the day before, along with a brigade left behind from Slocum's corps after Meade moved the rest down the line. Cemetery Hill was held by the survivors of Howard's three divisions of "Dutchmen", who had also taken a beating the previous day and who were not noted for holding their ground to begin with. Ewell's force actually outnumbered the defenders, but the terrain was nasty and the Yankees had been sensibly working hard to fortify it.

The Confederate attack jumped off at about 7:00 PM, with one of Ewell's divisions under General Edward Johnson moving on Culp's Hill. They quickly ran into trouble. Wadsworth's division held the northeast part of the hill, and though his men had been battered the day before they still had plenty of fight left in them, particular the survivors of the Iron Brigade; they were confident in their defenses, and not inclined to abandon them.

The attackers seemed to be making much better progress on the western slopes of the hill, overrunning fortifications that had been abandoned when Meade had shifted the troops manning them south. That was deceptively encouraging, as the rebels found out when they ran into another set of fortifications that were sited at a right angle to the older defenses.

This was the brigade Slocum had left behind, New Yorkers under 62-year-old Brigadier General George Sears Greene. Greene was an easy-going man whose troops called him "the Old Man" or just "Pops", and he looked more like a farmer than an officer. In fact, he was a "grim old fighter", as his officers put it. He had graduated second in his class at West Point, and then had gone on to civilian life to become a high-profile civil engineer. With expertise like that available, the Federal defenses had been made very strong, and the New Yorkers fought with determination. The fighting on Culp's Hill went on until darkness put a stop to it, to presumably be resumed when the sun came up again.

* Following Johnston's attack on Culp's Hill, Early launched an assault against the Federal defenses on Cemetery Hill, committing two brigades of the four in his division. The two brigades included one brigade of Louisianans, the famous Louisiana Tigers under Brigadier General Harry T. Hays, and one brigade of North Carolinans under Colonel Isaac Avery.

Despite the fact that the Federals had built three lines of defenses on the hill, the Confederates drove forward until they reached the saddle between Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill, and then advanced up the steep slopes of Cemetery Hill. Increasing darkness and black-powder smoke made Federal fire inaccurate, and many of the "Dutchmen" had no nerve for a fight; rebel casualties were surprisingly light, though Avery was mortally wounded at the beginning of the attack.

Union General Howard was there among his soldiers, and reported later: "Almost before I could tell where the assault was made, our men and the Confederates came tumbling back together." Howard and Schurz remained calm; Schurz immediately found two regiments of soldiers to throw back at the Confederates.

The rebels were among the guns on top of the hill and had it out with the artillerymen there hand to hand. One Confederate officer cried out: "This battery is ours!" A Federal gunner hit him with a spongestaff and replied: "No, dis battery is UNSER!"

Winfield Scott Hancock had been watching the commotion to the north, and told John Gibbon: "We ought to send some help over there." The fighting increased in pitch, and Hancock said: "Sent a brigade. Send Carroll."

Colonel Samuel Sprig Carroll, a hard fighter, led his men at a run to the battlefield. When they got in range, they began to fire volleys into the rebel ranks. The Confederates, thinking in the twilight that the troops coming up on might be fellow rebels shooting at them in error, held their fire until the Yankees were almost on top of them. They finally realized the new arrivals really were enemies and began to fight back, but the Federals had the initiative, while those troops of Howard's who were not too stampeded were now rallying and throwing their weight into the counterattack. The Confederates held out for a while, but lacking reinforcements they decided to withdraw back down the hill, leaving behind dead and wounded. Ewell had reinforcements he could have sent into the fight, but he failed to commit them.

* The sun went down on 2 July after a brutal afternoon and evening of fighting. The struggle had been a chaotic nightmare even by the rough standards of warfare, with soldiers demonstrating extreme courage and ferocity while their leadership demonstrated little ability to direct the battle.

The casualties had been tremendous. On the Union side, Sickles' III Corps had been all but destroyed, and all the Federal units involved in the fighting had been badly torn up. Dan Sickles was out of the war for good, though he would survive to run unsuccessfully for the US presidency later, displaying his missing leg as an authentic badge of honor. He would quarrel with Meade for years over the deployment of his men to the Peach Orchard.

The First Minnesota regiment under Colonel Colvill that Hancock had thrown to the wolves to slow down the assault of Anderson's brigades had gone into the fight with 262 men and come back with 47. Among the dead were Colvill himself. Another prominent Union casualty was Colonel Cross, pulled wounded from the field. He died before midnight in a field hospital, saying: "I did hope I would live to see peace and our country restored. I think my boys will miss me."

Brigadier General Stephen Weed, his spine severed on Little Round Top, was in a field hospital that night, and an aide visited him to ask him how he was. Weed replied: "I'm as dead a man as Julius Caesar." -- breathed his last a short time later. Confederate Brigadier General Barksdale, with five wounds, was amazingly still alive when Federal scouts picked him up off the battlefield after the fighting died down, but Barksdale did not live to see the sun come up the next morning.

The rebels had taken a mauling, with severe casualties in the divisions of Hood, McLaws, Anderson, Johnson, and Early. Hood was out of action for some time, and brigade commanders such as Semmes and Barksdale were dead. For whatever satisfaction it gave them, the rebels at least could point to the fact that they had pressed the Federals very hard on the southern end of their defensive line, nearly penetrating it several times even though they faced larger Yankee forces. The valor of the rebels could not make up for the lack of coordination in their attacks -- and even if they had pressed the Federals harder, Meade had plenty of reinforcements at his disposal, and could have moved them quickly along his interior lines of communication. Sheer guts could accomplish great things, but the Confederates were outnumbered.

Lee had been pleased with the progress made by the assaults of his men, and was aware that they had not been followed up. However, he had been largely a passive observer during the day's fighting, sending and receiving few messages. The Federals had not shown much more art on the battlefield, and managed to blunt the rebel attacks only by throwing in reinforcements as fast as they could to threatened sectors. Governeur Warren summed it up neatly, and also provided a word of advice from a combat soldier to generations of armchair strategists, saying that the fight "was no display of scientific maneuver, and should never be judged like some I think vainly try to judge a battle as they would a game a chess."

BACK_TO_TOP